1. Introduction: Two related puzzles

The vast majority of humans today live in large-scale, anonymous societies. This is a remarkable and puzzling fact because, prior to roughly 12,000 years ago,Footnote 1 most people lived in relatively small-scale tribal societies (Johnson & Earle Reference Johnson and Earle2000), which themselves had emerged from even smaller-scale primate troops (Chapais Reference Chapais2008). This dramatic scaling up appears to be linked to changes that occurred after the stabilization of global climates at the beginning of the Holocene, when food production began to gradually replace hunting and foraging, and the scale of human societies started to expand (Richerson et al. Reference Richerson, Boyd and Bettinger2001). Even the earliest cities and towns in the Middle East, not to mention today's vast metropolises with tens of millions of people, contrast sharply with the networks of foraging bands that have characterized most of the human lineage's evolutionary history (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Walker, Božičević, Eder, Headland, Hewlett, Hurtado, Marlowe, Wiessner and Wood2011).

The rise of stable, large, cooperative societies is one of the great puzzles of human history, because the free-rider problem intensifies as groups expand. Proto-moral sentiments that are rooted in kin selection and reciprocal altruism have ancient evolutionary origins in the primate lineage (de Waal Reference de Waal2008), and disapproval of antisocial behavior emerges even in preverbal babies (Bloom Reference Bloom2013; Hamlin et al. Reference Hamlin, Wynn and Bloom2007). However, neither kin selection nor reciprocal altruism (including partner-choice mechanisms) can explain the rise of large, cooperative, anonymous societies (Chudek & Henrich Reference Chudek and Henrich2011; Chudek et al. Reference Chudek, Zhao, Henrich, Joyce, Sterelny and Calcott2013). Genealogical relatedness decreases geometrically with increasing group size, and strategies based on direct or indirect reciprocity fail in expanding groups (Boyd & Richerson Reference Boyd and Richerson1988) or as reputational information becomes increasingly noisy or unavailable (Panchanathan & Boyd Reference Panchanathan and Boyd2003). Without additional mechanisms to galvanize cooperation, groups collapse, fission, or feud, as has been shown repeatedly in small-scale societies (Forge Reference Forge, Ucko, Tringham and Dimbelby1972; Tuzin Reference Tuzin2001). Our first puzzle, then, is how some groups, made up of individuals equipped with varying temperaments and motivations, which evolved and calibrated for life in relatively small-scale ancestral societies, were able to dramatically expand their size and scale of cooperation while sustaining mutually beneficial exchange. How was this feat possible on a time scale of thousands of years, a rate too slow to be driven by demographic growth processes and too fast for substantial genetic evolution?Footnote 2

Consider our second puzzle. Over the same time period, prosocial religions emerged and spread worldwide, to the point that the overwhelming majority of believers today are the cultural descendants of a very few such religions. These religions elicit deep devotions and extravagant rituals, often directed at Big Gods: powerful, morally concerned deities who are believed to monitor human behavior. These gods are believed to deliver rewards and punishments according to how well people meet the particular, often local, behavioral standards, including engaging in costly actions that benefit others. Whereas there is little dispute that foraging societies possess beliefs in supernatural agents, these spirits and deities are quite different from those of world religions, with only limited powers and circumscribed concerns about human morality. It appears that interrelated religious elements that sustain faith in Big Gods have spread globally along with the expansion of complex, large-scale human societies. This has occurred despite their rarity in small-scale societies or during most of our species' evolutionary history (Norenzayan Reference Norenzayan2013; Swanson Reference Swanson1960).

Connecting these two puzzles, we argue that cultural evolution, driven by the escalating intergroup competition particularly associated with settled societies, promoted the selection and assembly of suites of religious beliefs and practices that characterize modern prosocial religions. Prosocial religions have contributed to large-scale cooperation, but they are only one among several likely causes. Religious elements are not a necessary condition for cooperation or moral behavior of any scale (Bloom Reference Bloom2012; Norenzayan Reference Norenzayan2014). There are several other cultural evolutionary paths to large-scale cooperation, including institutions, norms, and practices unrelated to prosocial religions. These include political decision making (e.g., inherited leadership positions), social organization (e.g., segmentary lineage systems), property rights, division of labor (e.g., castes), and exchange and markets. The causal effects of religious elements can interact with all of these domains and institutions, and this causality can run in both directions, in a feedback loop between prosocial religions and an expanded cooperative sphere.

This cultural evolutionary process selects for any psychological traits, norms, or practices that (1) reduce competition among individuals and families within social groups; (2) sustain or increase group solidarity; and (3) facilitate differential success in competition and conflict between social groups by increasing cooperation in warfare, defense, demographic expansion, or economic ventures. This success can then lead to the differential spread of particular religious elements, as more successful groups are copied by less successful groups, experience physical or cultural immigration, expand demographically through higher rates of reproduction, or expand through conquest and assimilation. It was this cultural evolutionary process that increasingly intertwined the “supernatural” with the “moral” and the “prosocial.” For this reason, we refer to these culturally selected and now dominant clusters of elements as prosocial religions. Footnote 3

We have been developing the converging lines of this argument over several years in several places (e.g., Atran & Henrich Reference Atran and Henrich2010; Henrich Reference Henrich2009; Norenzayan Reference Norenzayan2013; Norenzayan & Shariff Reference Norenzayan and Shariff2008; Slingerland et al. Reference Slingerland, Henrich, Norenzayan, Richerson and Christiansen2013). Here, we synthesize and update this prior work and further develop several empirical, theoretical, and conceptual aspects of it. Empirically, we discuss the historical and ethnographic evidence at greater depth and lay out the findings from a new meta-analysis of religious priming studies that specify underlying psychological processes and boundary conditions. Theoretically, we discuss in greater detail one key part of the process that we hypothesize gave rise to prosocial religions: cultural group selection. We also integrate sacred values into our framework, review alternative scenarios linking some religious elements with large-scale societies, and tackle counterarguments. Overall, we bring together evidence from available historical and ethnographic observation with experimental studies that address several interrelated topics, including signaling, ritual, religious priming, cognitive foundations of religion, behavioral economics, cooperation, and cultural learning.

This account paves the way for a cognitive–evolutionary synthesis, consolidating several key insights. These include (1) how innate cognitive mechanisms gave rise, as a by-product, to supernatural mental representations (Atran & Norenzayan Reference Atran and Norenzayan2004; Barrett Reference Barrett2000; Boyer Reference Boyer2001; Lawson & McCauley Reference Lawson and McCauley1990; McCauley Reference McCauley2011); (2) how natural selection shaped cognitive abilities for cultural learning, making humans a culture-dependent species with divergent cultural evolutionary trajectories (Richerson & Boyd Reference Richerson and Boyd2005); and (3) how intergroup competition shaped cultural evolution, giving rise to cultural group selection and gene–culture coevolution (Chudek & Henrich Reference Chudek and Henrich2011; Henrich Reference Henrich2004). We hypothesize that by building on these foundations, cultural evolution has harnessed a variety of proximate psychological mechanisms to shape and consolidate human beliefs, actions, and commitments that converge in increasingly prosocial religions. The result is an account that recognizes, synthesizes, and extends earlier and contemporary insights about the social functions of religious elements (Durkheim Reference Durkheim1915; Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Rappaport Reference Rappaport1999; Sosis & Alcorta Reference Sosis and Alcorta2003; Wilson Reference Wilson2003).

We begin with the idea that religious elements arose as a nonadaptive evolutionary by-product of ordinary cognitive functions (Atran & Norenzayan Reference Atran and Norenzayan2004; Barrett Reference Barrett2004; Bloom Reference Bloom2004; Boyer Reference Boyer1994). However, we move beyond cognitive by-product approaches by tackling historical trajectories and cross-cultural trends in religious beliefs and behaviors, particularly dominant elements of modern religions that are hard to explain in the absence of cultural evolutionary processes and selective cultural transmission. We argue that although religious representations are rooted in innate aspects of cognition, only some of the possible cultural variants then spread at the expense of other variants because of their effects on success in intergroup competition.

Drawing on contributions from adaptationist approaches to religion (Bering Reference Bering2006; Reference Bering2011; Bulbulia Reference Bulbulia, Bulbulia, Richard, Genet, Harris, Wynan and Genet2008; Cronk Reference Cronk1994; Johnson & Bering Reference Johnson and Bering2006; Johnson Reference Johnson and Levin2009; Sosis & Alcorta Reference Sosis and Alcorta2003; Sosis & Bulbulia Reference Sosis and Bulbulia2011), we take seriously the important role that religious elements appear to play in shaping the lives of individuals and societies, and we recognize that there are crucial linkages among rituals, belief in supernatural monitors, and cooperation that these approaches have illuminated across diverse environmental and cultural contexts. Our contribution builds on evolved psychological mechanisms, but it also explores in great detail the cultural learning dynamics and the historical processes that shape religions and rituals in both adaptive and maladaptive ways. We therefore argue that our framework reconciles key aspects and insights from the adaptationist and by-product approaches. It also tackles a range of empirical observations, including some that have not been adequately addressed, and generates novel predictions ripe for investigation. As such, we present this synthesis as an invitation for a conversation and debate about core issues in the evolutionary study of religion.

2. Theoretical foundations

Our synthesis rests on four conceptual foundations: (1) the reliable development of cognitive mechanisms that constrain and influence the transmission of religious beliefs; (2) evolved social instincts that drive concerns about third-party monitoring, which in turn facilitate belief in and response to supernatural monitoring; (3) cultural learning mechanisms that guide the spread of specific religious contents and behaviors; and (4) intergroup competition that influences the cultural evolution of religious beliefs and practices.

2.1. Reliably developing cognitive biases for religion

The cognitive science of religion has begun to show that religious beliefs are rooted in a suite of core cognitive faculties that reliably develop in individuals across populations and historical periods (Atran & Norenzayan Reference Atran and Norenzayan2004; Barrett Reference Barrett2004; Bloom Reference Bloom2012; Boyer Reference Boyer2001; Guthrie Reference Guthrie1993; Kirkpatrick Reference Kirkpatrick1999; Lawson & McCauley Reference Lawson and McCauley1990). As such, “religions” are best seen as constrained amalgams of beliefs and behaviors that are rooted in core cognitive tendencies. Examples of particular interest here are (1) mentalizing (Bering Reference Bering2011; Frith & Frith Reference Frith and Frith2003; Waytz et al. Reference Waytz, Gray, Epley and Wegner2010), (2) teleological thinking (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2004), and (3) mind–body dualism (Bloom Reference Bloom2007; Chudek et al. Reference Chudek, MacNamara, Birch, Bloom and Henrich2015). Consistent with these hypotheses, individual differences in these tendencies partly explain the degree to which people believe in God, in paranormal events, and in life's meaning and purpose (Willard & Norenzayan Reference Willard and Norenzayan2013).

These cognitive tendencies can be harnessed by cultural evolution (they provide potential raw material) in constructing particular elements of religions or other aspects of culture. However, cultural evolution need not harness all or any of these cognitive tendencies. Our argument is that some of them have been drafted by cultural evolution in more recent millennia to underpin particular supernatural beliefs, such as an afterlife contingent on proper behavior in this life, because those beliefs promoted success in intergroup competition, although none of those cognitive processes are solely or uniquely involved in religion.

Most relevant to prosocial religions is the evolved capacity for mentalizing (Epley & Waytz Reference Epley, Waytz, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindsay2010; Frith & Frith Reference Frith and Frith2003), which makes possible the cultural recruitment of supernatural agent beliefs (Gervais Reference Gervais2013). Mentalizing, also known as “theory of mind,” allows people to detect and infer the existence and content of other minds. It also supplies the cognitive basis for the pervasive belief in disembodied supernatural agents such as gods and spirits. Believers treat gods as beings who possess humanlike goals, beliefs, and desires (Barrett & Keil Reference Barrett and Keil1996; Bering Reference Bering2011; Bloom & Weisberg Reference Bloom and Weisberg2007; Epley et al. Reference Epley, Waytz and Cacioppo2007; Guthrie Reference Guthrie1993). This mentalizing capacity enables them to believe they interact with gods, who are thought to respond to existential anxieties, such as anxieties about death and randomness (Atran & Norenzayan Reference Atran and Norenzayan2004), and engage in social monitoring (Norenzayan & Shariff Reference Norenzayan and Shariff2008). Consistent with the by-product argument that religious thinking recruits ordinary capacities for mind perception, thinking about or praying to God activates brain regions associated with theory of mind (Kapogiannis et al. Reference Kapogiannis, Barbey, Su, Zamboni, Krueger and Grafman2009; Schjoedt et al. Reference Schjoedt, Stødkilde-Jørgensen, Geertz and Roepstorff2009); and reduced mentalizing tendencies or abilities, as found in the autistic spectrum, predicts reduced belief in God (Norenzayan et al. Reference Norenzayan, Gervais and Trzesniewski2012). Conversely, schizotypal tendencies that include promiscuous anthropomorphizing are associated with “hyper-religiosity” (Crespi & Badcock Reference Crespi and Badcock2008; Willard & Norenzayan Reference Willard and Norenzayan2015).

2.2. Social instincts and third-party monitoring

Humans likely evolved in a social world governed by community-wide norms or shared standards in which the community conducted surveillance for norm violations and sanctioning (Chudek & Henrich Reference Chudek and Henrich2011; Chudek et al. Reference Chudek, Zhao, Henrich, Joyce, Sterelny and Calcott2013). This reputational aspect of our norm psychology means that humans are sensitive to cues of social monitoring (Bering & Johnson Reference Bering and Johnson2005), attend keenly to social expectations and public observation (Fehr & Fischbacher Reference Fehr and Fischbacher2003), and anticipate a world governed by social rules with sanctions for norm violations (Chudek & Henrich Reference Chudek and Henrich2011; Fehr et al. Reference Fehr, Fischbacher and Gächter2002). Relevant empirical work indicates that sometimes exposure to even subtle cues, such as drawings of eyes, can increase compliance to norms related to fairness and not stealing (Haley & Fessler Reference Haley and Fessler2005; Rigdon et al. Reference Rigdon, Ishii, Watabe and Kitayama2009; Zhong et al. Reference Zhong, Bohns and Gino2010; but see Fehr & Schneider Reference Fehr and Schneider2010), even in naturalistic settings (Bateson et al. Reference Bateson, Nettle and Roberts2006). If the presence of human watchers encourages norm compliance, then it is not surprising that the suggestion of morally concerned supernatural watchers – with greater surveillance capacities and powers to punish – might expand norm compliance beyond that associated with mere human watchers and earthly sanctions (e.g., Bering Reference Bering2011). We argue that intergroup competition (discussed subsequently) exploits this feature of human social psychology, among others, to preferentially select belief systems with interventionist supernatural agents concerned about certain kinds of behaviors.

2.3. Cultural learning and the origins of faith

Humans are a cultural species (Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, Richerson and Henrich2011b). More than in any other species, human cultural learning generates vast bodies of know-how and complex practices that adaptively accumulate over generations (Tomasello Reference Tomasello2001). To have adaptive benefits, cultural learning involves placing faith in the products of this process and often overriding our innate intuitions or individual experiences (Beck Reference Beck1992; Henrich Reference Henrich2015). Children and adults from diverse societies accurately imitate adults' seemingly unnecessary behaviors (they “over-imitate”), even when they are capable of disregarding them (Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Young and Keil2007; Nielsen & Tomaselli Reference Nielsen and Tomaselli2010). This willingness to rely on faith in cultural traditions – over personal experience or intuition – has profound implications for explaining key features of religions (Atran & Henrich Reference Atran and Henrich2010).

Much theoretical and empirical work suggests that, when deciding to place faith in cultural information over other sources, learners rely on a variety of cues that include the following:

-

1. Content-based mechanisms, which lead to the selective retention and transmission of some mental representations over others because of differences in their content (Boyer Reference Boyer2001; Sperber Reference Sperber1996). For example, emotionally evocative and socially relevant ideas are more memorable and, therefore, culturally contagious (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Bell and Sternberg2001; Stubbersfield et al. Reference Stubbersfield, Tehrani and Flynn2015; see also Broesch et al. Reference Broesch, Henrich and Barrett2014).

-

2. Context-based mechanisms (or model-based cultural learning biases), which arise from evolved psychological mechanisms that encourage learners to attend to and learn from particular individuals (cultural models) based on cues such as skill, success, prestige, self-similarity (Henrich & Gil-White Reference Henrich and Gil-White2001), and trait frequency (Perreault et al. Reference Perreault, Moya and Boyd2012; Rendell et al. Reference Rendell, Fogarty, Hoppitt, Morgan, Webster and Laland2011).

-

3. Credibility-enhancing displays (CREDs), or learners' sensitivity to cues that a cultural model is genuinely committed to his or her stated or advertised beliefs. If models engage in behaviors that would be unlikely if they privately held opposing beliefs, learners are more likely to trust the sincerity of the models and, as a result, adopt their beliefsFootnote 4 (Henrich Reference Henrich2009; see also Harris Reference Harris2012; Sperber et al. Reference Sperber, Clément, Heintz, Mascaro, Mercier, Origgi and Wilson2010).

All three classes of learning mechanisms are crucial to understanding how religious beliefs and practices are transmitted and stabilized, why certain rituals and devotions can substantially influence cultural transmission, and why some elements of religions are recurrent and others culturally variable (Gervais et al. Reference Gervais, Willard, Norenzayan and Henrich2011b). To date, content-based mechanisms have been the main focus and the source of much progress in the cognitive science of religion. This includes work on minimally counterintuitive concepts (Boyer & Ramble Reference Boyer and Ramble2001; but see Purzycki & Willard, Reference Purzycki and Willardin press), folk notions of mind–body dualism (Bloom Reference Bloom2004), and hyperactive agency detection (Barrett Reference Barrett2004). We argue, however, that context-based cultural learning and CREDs are equally important if we wish to construct a comprehensive account of the differential spread of religious beliefs and behaviors. For example, because people are biased to preferentially acquire religious beliefs and practices from the plurality and from prestigious models in their communities, identical or similar god concepts can be the object of deep commitment in one historical period but then a fictional character in another (Gervais & Henrich Reference Gervais and Henrich2010; Gervais et al. Reference Gervais, Willard, Norenzayan and Henrich2011b). Also, CREDs help us explain why religious ideas backed up by credible displays of commitment (such as fasts, sexual abstinence, and painful rituals) are more persuasive and more likely to spread. In turn, we see why such extravagant displays are commonly found in prosocial religions and tied to deepening commitment to supernatural agents. Moreover, core intuitions about supernatural beings and ritual-behavior complexes, once in place, coexist with other ordinary intuitions and causal schemata in everyday life (Legare et al. Reference Legare, Evans, Rosengren and Harris2012).

2.4. The cultural group selection of prosocial religions

We propose that prosocial religions are shaped by cultural group selection, a class of cultural evolutionary processes that considers the impact of intergroup competition on cultural evolutionary outcomes. These processes have been studied extensively and have a long intellectual history (Boyd & Richerson Reference Boyd, Richerson and Mansbridge1990; Darwin Reference Darwin1871; Hayek Reference Hayek and Bartley1988; Khaldun Reference Khaldun and Rosenthal1958). Intergroup competition has potentially been shaping cultural evolution over much of our species' evolutionary history, altering the genetic selection pressures molding the foundations of our sociality (Henrich Reference Henrich2015; Richerson & Boyd Reference Richerson and Boyd1999). However, as the origins of agriculture made large, settled, populations economically possible across diverse regions during the last 12 millennia, a regime of intensive intergroup competition ensued that increased the size and complexity of human societies (Alexander Reference Alexander1987; Bowles Reference Bowles2008; Carneiro Reference Carneiro1970; Currie & Mace Reference Currie and Mace2009; Otterbein Reference Otterbein1970; Turchin Reference Turchin2003; Turchin et al. Reference Turchin, Currie, Turner and Gavrilets2013).

A class of evolutionary models has revealed broad conditions under which cultural group selection can influence the trajectory of cultural evolution. Intergroup competition can operate through violent conflict, but also through differential migration into more successful groups, biased copying of practices and beliefs among groups, and differential extinction rates without any actual conflict (Richerson et al., Reference Richerson, Hillis, Newson, Baldini, Frost, Bell, Demps, Mathew, Newton, Narr, Ross, Smaldino, Waring and Zeffermanin press). These models show that the conditions under which intergroup competition substantially influences cultural evolution are much broader than for genetic evolution (Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, Gintis and Richerson2003; Reference Boyd, Richerson and Henrich2011a; Guzman et al. Reference Guzman, Rodriguez-Sickert and Rowthorn2007; Henrich & Boyd Reference Henrich and Boyd2001; Smaldino Reference Smaldino2014). This is in part because cultural evolution can sustain behavioral variation among groups, which drives the evolutionary process to a degree that genetic evolution does not (Bell et al. Reference Bell, Richerson and McElreath2009; Henrich Reference Henrich2012; Richerson et al., Reference Richerson, Hillis, Newson, Baldini, Frost, Bell, Demps, Mathew, Newton, Narr, Ross, Smaldino, Waring and Zeffermanin press).

Empirically, there are several converging lines of evidence supporting the importance of intergroup competition, including data from laboratory studies (Gurerk et al. Reference Gürerk, Irlenbusch and Rockenbach2006; Saaksvuori et al. Reference Saaksvuori, Mappes and Puurtinen2011), archaeology (Flannery & Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2000; Spencer & Redmond Reference Spencer and Redmond2001), history (Turchin Reference Turchin2003; Turchin et al. Reference Turchin, Currie, Turner and Gavrilets2013), and ethnographic or ethnohistorical studies (Atran Reference Atran2002; Boyd Reference Boyd2001; Currie & Mace Reference Currie and Mace2009; Kelly Reference Kelly1985; Soltis et al. Reference Soltis, Boyd and Richerson1995; Wiessner & Tumu Reference Wiessner and Tumu1998). See Richerson et al. (Reference Richerson, Hillis, Newson, Baldini, Frost, Bell, Demps, Mathew, Newton, Narr, Ross, Smaldino, Waring and Zeffermanin press) for a recent review, and Henrich (Reference Henrich2015) for the importance of intergroup competition among hunter–gatherers.

Although these studies provide evidence of the competitive process in action, experimental evidence reveals that larger and more economically successful groups have stronger prosocial norms: a pattern consistent with cultural group selection models. For example, in a global sample of roughly a dozen diverse populations, individuals from larger ethnolinguistic groups and larger communities were more willing to incur a cost to punish unfair offers in experimental games (Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Ensimger, McElreath, Barr, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Lesorogol, Marlowe, Tracer and Ziker2010a; Reference Henrich, Ensminger, Barr, McElreath, Ensminger and Henrich2014), a result that held after controlling for a range of economic and demographic variables (see also Marlowe et al. Reference Marlowe, Berbesque, Barr, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Ensminger, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Henrich, Lesorogol, McElreath and Tracer2008). Even among Hadza foragers, larger camps are more often prosocial in economic games (Marlowe Reference Marlowe, Henrich, Boyd, Bowles, Camerer, Fehr and Gintis2004). Similarly, in a detailed study in Tanzania, Paciotti and Hadley (Reference Paciotti and Hadley2003) compared the economic game playing of two ethnolinguistic groups living side by side, the Pimbwe and the Sukuma. The institutionally more complex Sukuma had been rapidly expanding their territory over several generations, and they played much more prosocially in the Ultimatum Game than did the Pimbwe. Cross-nationally, experimental work also reveals a negative correlation between gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and both people's motivations to punish cooperators in a public goods game (stifling cooperation) and their willingness to cheat to favor themselves or their local “in” group (Hermann et al. Reference Herrmann, Thoni and Gächter2008; Hruschka et al. Reference Hruschka, Efferson, Jiang, Falletta-Cowden, Sigurdsson, McNamara, Sands, Munira, Slingerland and Henrich2014).

Broadly speaking, therefore, cultural group selection favors complexes of culturally transmitted traits – beliefs, values, practices, rituals, and devotions – that (1) reduce competition and variation within social groups (sustaining or increasing social cohesion) and (2) enhance success in competition with other social groups, by increasing factors such as group size, cooperative intensity, fertility, economic output, and bravery in warfare. Thus, any cultural traits – connected to the supernatural or not – that directly or indirectly promoted parochial prosociality in expanded groups (Bowles Reference Bowles2006; Choi & Bowles Reference Choi and Bowles2007) could be favored. The issue at hand is whether the crucible of intensive cultural group selection that emerged with the origins of agriculture shaped the beliefs, commitments, institutions, and practices associated with religions in predictable ways over the last 12 millennia.Footnote 5

2.5. The theoretical synthesis

We build on these four foundations to construct a synthetic view of modern world religions. We begin from the premise that religious beliefs and behaviors originated as evolutionary by-products of ordinary cognitive tendencies, built on reliably developing panhuman cognitive templates. Some subset of these cultural variants happened to have incidental effects on within-group prosociality by increasing cooperation, solidarity, and group size. Such variants may have spread first, allowing groups to expand and economically succeed, or they may have spread in the wake of a group's successful expansion, subsequently adding sustainability to a group's cultural success. Competition among cultural groups, operating over millennia, gradually aggregated these elements into cultural packages (“religions”) that were increasingly likely to include the following:

-

1. Belief in, and commitment to, powerful, all-knowing, and morally concerned supernatural agents who are believed to monitor social interactions and to reward and sanction behaviors in ways that contribute to the cultural success of the group, including practices that effectively transmit the faith. Rhetorically, we call these “Big Gods,” but we alert readers that we are referring to a multidimensional continuum of supernatural agents in which Big Gods occupy a particular corner of the space. By outsourcing some monitoring and punishing duties to these supernatural agents, prosocial religions reduce monitoring costs and facilitate collective action, which allows groups to sustain in-group cooperation and harmony while expanding in size.

-

2. Ritual and devotional practices that effectively elevate prosocial sentiments, galvanize solidarity, and transmit and signal deep faith. These practices exploit human psychology in a host of different ways, including synchrony to build in-group solidarity, CREDs and signals (e.g., sacrifices, painful initiations, celibacy, fasting), and other cultural learning biases (conformity, prestige, and age) to more effectively transmit commitment to others.

-

3. Additional beliefs and practices that exploit aspects of psychology to galvanize group cohesion and increase success. These include fictive kinship for coreligionists; in-group (“ethnic”) markers to spark tribal psychology, exclude the less committed, and mark religious boundaries; pronatalist norms that increase fertility rates; practices that increase self-control and the suppression of self-interest; and seeing a divine origin in certain beliefs and practices, transforming them into “sacred” values that are nonnegotiable.

2.6. Hypotheses

Here we list some specific hypotheses that follow from the present theoretical framework.

-

1. Big Gods spread because they contributed to the expansion of cooperative groups. Historically, they coevolved gradually with larger and increasingly more complex societies. In turn, larger and more complex societies might have been more likely to transmit and sustain belief in such gods, creating autocatalytic processes that energized each other. One consequence of this process is that group size and long-term stability should positively correlate with the prevalence of Big Gods.

-

2. All things being equal, commitment to Big Gods should produce more norm compliance in difficult-to-monitor situations, relative to belief in supernatural agents that are unable or unwilling to omnisciently monitor and punish.

-

3. Religious behavior that signals genuine devotion to the same or similar gods would be expected to induce greater cooperation and trust among religious members. Conversely, a lack of any devotion to any moralizing deities (i.e., atheism or amoral supernatural agents) should trigger distrust.

-

4. These cultural packages include rituals and devotions that exploit costly and extravagant displays to deepen commitment to Big Gods, as well as other solidarity and self-control-building cultural technologies (e.g., synchrony, repetition) and cultural learning biases (e.g., prestige) that more effectively transmit the belief system.

-

5. Cultural groups with this particular constellation of beliefs, norms, and behaviors (i.e., prosocial religious groups) should enjoy a relative cultural survival advantage, especially when intergroup competition over resources and adherents is fierce.

In the sections that follow, we confront these hypotheses with the available empirical data.

To address these hypotheses, we first draw on a combination of ethnographic, historical, and archaeological data to show exactly how different modern prosocial religions are from the religions of small-scale societies, and likely from those of our Paleolithic ancestors. This difference is important, because much theorizing by psychologists about the origins of religion often presumes that modern gods are culturally typical gods rather than being the products of a particular cultural evolutionary trajectory. Second, we examine the relationship between commitment to modern world religions and prosocial behavior by reviewing correlational data from surveys and behavioral studies, as well as experimental findings from religious priming studies to address causality. Third, we examine religion's role in building intragroup trust, as well as commitment mechanisms that galvanize social solidarity and transmit faith. Fourth, we evaluate evidence for the cultural group selection of prosocial religions. Finally, we situate this framework within existing evolutionary perspectives, address counter-explanations and alternative cultural evolutionary scenarios, discuss secularization, and conclude with outstanding questions and future directions.

3. Big Gods and ritual forms emerge and support large-scale societies

The anthropological record indicates that, in moving from the smallest scale human societies to the largest and most complex societies, the following empirical patterns emerge: (1) beliefs in Big Gods change from being relatively rare to being increasingly common, as these supernatural agents gain more power, knowledge, and concern about morality; (2) morality and supernatural beliefs move from being mostly disconnected to being increasingly intertwined; (3) rituals become increasingly organized, repetitious, and regular; (4) supernatural punishments are increasingly focused on violations of group beneficial norms (e.g., prohibiting theft from coreligionists, including those who are strangers, or demanding faith-deepening sacrifices); and (5) the potency of supernatural punishment and reward increases for key social norms (e.g., salvation, karma, hell, and heaven). These patterns are supported by both ethnographic and historical evidence.

3.1. Anthropological evidence

Quantitative and qualitative reviews of the anthropological record suggest that the gods of small-scale societies, especially those found in the foraging societies often associated with life in the Paleolithic, are typically cognitively constrained and have limited or no concern with human affairs or moral transgressions (Boehm Reference Boehm, Bulbulia, Sosis, Harris, Genet, Genet and Wyman2008; Boyer Reference Boyer2001; Swanson Reference Swanson1960; Wright Reference Wright2009). For example, among the much studied hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari region, Marshall (Reference Marshall1962) wrote, “Man's wrong-doing against man is not left to Gao!na's [the relevant god's] punishment nor is it considered to be his concern. Man corrects or avenges such wrong-doings himself in his social context”Footnote 6 (p. 245). Although some of these gods are pleased with rituals or sacrifices offered to them, they play a small or no part in the elaborate cooperative lives of foraging societies, and they rarely concern themselves with norm violations, including how community members treat each other or strangers. However, as the size and complexity of societies increase, more powerful, interventionist, and moralizing gods begin to appear. Quantitative analyses of the available anthropological databases, including the Standard Cross Cultural Sample (SCCS), which provides data for 167 societies, selected to reduce historical relationships, and the Ethnographic Atlas (724 societies), show positive correlations between the prevalence of Big Gods and societal size, complexity, population density, and external threats (Roes Reference Roes1995; Roes & Raymond Reference Roes and Raymond2003; Reference Roes and Raymond2009). These quantitative data also show that powerful moralizing gods appear in <10% of the smallest-scale human societies but become widespread in large-scale societies (see Fig. 1). This empirical finding dates back to Swanson (Reference Swanson1960), and despite critiques (Underhill Reference Underhill1975) and the statistical control of potential confounding variables (e.g., missionary activity, population density, economic inequality, geographic regions), the basic finding still holds.

Figure 1. Increasing prevalence of Big Gods as a function of social group size in the Standard Cross Cultural Sample (reprinted from Evolution and Human Behavior, Roes, F. L. & Raymond, M., Vol. 24, issue 2, Belief in moralizing gods, pp. 126–35, copyright 2003, with permission from Elsevier.).

Other researchers have arrived at similar conclusions. Stark (Reference Stark2001), for example, found that only 23.9% of 427 preindustrial societies in the Ethnographic Atlas (Murdock Reference Murdock1981) possess a god that was active in human affairs and was specifically supportive of human morality. Johnson's (Reference Johnson2005) analysis supports earlier results, and it also reveals correlations linking the presence of powerful moralizing gods to variables related to exchange, policing, and cooperation in larger, more complex societies (see also Sanderson & Roberts Reference Sanderson and Roberts2008). Such gods are also more prevalent in societies with water scarcity, another key threat to group survival (Snarey Reference Snarey1996). In a different analysis, Peoples and Marlowe (Reference Peoples and Marlowe2012) found several statistically independent predictors of Big Gods: (1) society size, (2) agricultural mode of subsistence, and (3) animal husbandry. Botero et al. (Reference Botero, Gardner, Kirby, Bulbulia, Gavin and Gray2014) arrived at similar conclusions. Using high-resolution bioclimactic data, and after controlling for the potential nonindependence among societies, they found that, in addition to the previously examined predictors, societies with greater exposure to ecological duress are more likely to have a cultural belief in powerful moralizing gods. More stratified societies are also more likely to support such Big Gods, but this effect sometimes drops out in the presence of mode of subsistence and community size. Nevertheless, it has been hypothesized that one way that prosocial religions maintain social cohesion in expanding groups is by legitimizing authority, inequality, and hierarchical relations (e.g., Peoples & Marlowe Reference Peoples and Marlowe2012; Turchin Reference Turchin2011). In the absence of much intergroup competition, those factors can lead to exploitation by the elite. However, under intergroup competition, cultural evolution may favor such legitimizing beliefs to both sustain solidarity and reinforce command and control during crises. Overall, far from being a reliably developing product of evolved human cognition, the modern popularity of Big Gods is a historical and anthropological puzzle (Tylor Reference Tylor1871), and one that requires explanation.

We emphasize that, although these analyses typically impose a dichotomy on the ethnographic data, our theoretical approach treats them as a continuum, and it focuses on how intergroup competition influences the selection of cultural elements. For example, although most chiefdoms in Oceania do not possess what would be coded as a “moralizing high god,” there are ethnographic reasons to suspect that elements of mana and tapu, and supernatural punishment, may have been influenced by intergroup competition. These elements may have helped stabilize political leadership and may have kept people adhering to increasingly costly social norms. Archaeological and historical evidence, for example, indicates that the spread of divine kingship, spurred by interisland competition, was crucial for the emergence of a state in Hawaii (Kirch Reference Kirch2010). In the Fijian chiefdoms that we study ethnographically and experimentally, the strength of villagers' beliefs in punishing ancestor gods increases in-group biases in economic games (McNamara et al. Reference McNamara, Norenzayan and Henrich2016).

Organized rituals also follow a parallel pattern across societies. In an analysis using the Human Relations Area Files, Atkinson and Whitehouse (Reference Atkinson and Whitehouse2011) found that “doctrinal” rituals – the high-frequency, low-arousal rituals commonly found in modern world religions (Whitehouse Reference Whitehouse2004) – are associated with greater belief in Big Gods, reliance on agriculture, and societal complexity. We argue that, among other important roles, doctrinal rituals galvanize faith and deepen commitments to large, anonymous communities governed by these powerful gods.

3.2. Archaeological and historical evidence

These comparative anthropological insights converge with archaeological and historical evidence, suggesting that both Big Gods and routinized rituals and related practices coevolved with large, complex human societies, along with increasing reliance on food production.

3.2.1. Archaeological evidence

Although supernatural beliefs are hard to infer archaeologically, and such evidence should, therefore, be interpreted with caution, the material record in Mesoamerica indicates that rituals became more formal, elaborate, and costly as societies developed from foraging bands into chiefdoms and states (Marcus & Flannery Reference Marcus and Flannery2004). In Mexico before 4000 BP, for example, foraging societies relied on informal, unscheduled rituals just as modern foragers do (Lee Reference Lee1979). With the establishment of multivillage chiefdoms (4000–3000 BP), rituals expanded and distinct religious specialists emerged. After state formation in Mexico (2500 BP), key rituals were performed by a class of full-time priests using religious calendars and occupying temples built at immense costs. The same is also true of the earliest state-level societies of Mesopotamia after 5500 BP and India after 4500 BP. We find similar patterns in predynastic Egypt (6000–5000 BP) and China (4500–3500 BP), as well as in other North American chiefdoms. In China, for example, the beginning of the Bronze Age (ca. 1500 BCE) is accompanied by a radical elaboration in tomb architecture and burial practices of elites, indicating the emergence of highly centralized and stratified polities bound together by costly public religious ceremonies (Thote Reference Thote, Lagerwey and Kalinowski2009). Similar evidence for this can be found in Çatalhöyük, a 9500 BP Neolithic site in southern Anatolia (see Whitehouse & Hodder Reference Whitehouse, Hodder and Hodder2010).

3.2.2. Historical evidence

Once the written record begins, establishing links among large-scale cooperation, ritual elaboration, Big Gods, and morality becomes more tractable. To date, most of the historical work related to this topic focuses on the Abrahamic faiths. Wright (Reference Wright2009) provides a summary of textual evidence that reveals the gradual evolution of the Abrahamic god from a rather limited, whimsical, tribal war god – a subordinate in the Canaanite Pantheon – to the unitary, supreme, moralizing deity of two of the world's largest religious communities. We see the same dynamics at work in other major literate societies.

For example, although China has sometimes been portrayed as lacking moralizing gods, or even religion at all (Ames & Rosemont Reference Ames and Rosemont2009; Granet Reference Granet1934), scholars in recent years have begun systematically correcting that misconception (Clark & Winslett Reference Clark and Winslett2011; Slingerland Reference Slingerland2013). Although there are important ongoing debates about the importance of supernatural surveillance relative to other mechanisms (e.g., Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2015), in the earliest Chinese societies for which written records exist, the worshipped pantheon includes both the actual ancestors of the royal line and a variety of nature gods and cultural heroes, all under the dominion of a supreme deity, the “Lord on High” (shangdi) or Heaven (tian). This Lord on High/Heaven was a Big God in our sense, wielding supreme power over the natural world, intervening at will in the affairs of humans, and intensely concerned with prosocial values. The ability of the royal family to rule was a direct result of its possessing the “Mandate” (lit. “order” or “charge”) of Heaven, the possession of which was – at least by 1000 BCE or thereabouts – seen as being linked to moral behavior and proper observance of costly sacrificial and other ritual duties.

Surveillance by morally concerned supernatural agents also appears as a prominent theme in early China. Even from the sparse records from the Shang Dynasty, it is apparent that the uniquely broad power of the Lord on High to command a variety of events in the world led the Shang kings to feel a particular urgency about placating Him with proper ritual offerings. When the Zhou polity began to fragment into a variety of independent, and often conflicting, states (770–256 BCE), supernatural surveillance and the threat of supernatural sanctions remained at the heart of interstate diplomacy and internal political and legal relations (Poo Reference Poo2009). Finally, the written record reveals an increasingly clear connection in early China between morality and religious commitments. The outlines of moral behavior had been dictated by Heaven and encoded in a set of social norms, and a failure to adhere to these norms – either in outward behavior or in one's inner life – was to invite supernatural punishment (Eno Reference Eno, Lagerwey and Kalinowski2009).

Similarly, although the highly organized Greek city states and Imperial Rome are sometimes portrayed as possessing only amoral and fickle deities (e.g., see Baumard & Boyer Reference Baumard and Boyer2013), modern scholarship is increasingly rejecting this picture as the result of later Christian apologists' desire to distance the new Christian religion from “paganism.” The gods of the Greek city-states received costly sacrifices, were the subject of elaborate rituals, and played an active role in enforcing oaths and supporting public morality (Mikalson Reference Mikalson2010, pp. 150–68). Although Roman religion did not have sacred scriptures or an explicit moral code that was considered to be the word of the gods, the deities of imperial Rome were seen by the populace as the guardians of what was right and virtuous (Rives Reference Rives2007, pp. 50–52, 105–31), and the gods were central enough to the public sphere that even the spatial layouts of Roman cities were created around temples dedicated to the major gods (Rives Reference Rives2007, pp. 110–11).

One of the challenges of large-scale societies involves the trust necessary for many forms of exchange and credit, particularly long-distance trade (Greif Reference Greif2006). Not surprisingly, several Roman gods played a pivotal role in regulating marketplaces and in overseeing economic transactions. Cults dedicated to Mercury and Hercules in second- and first-century-BCE Delos – an important maritime trade center – emphasized public oaths certified by supernatural surveillance and divine punishment to overcome cooperation dilemmas in long-distance trade relations (Rauh Reference Rauh1993). In earlier periods, Greek, Roman, Sumerian, and Egyptian gods were also deeply involved in regulating the economic and public spheres. In surveying the Mediterranean region, Silver, for example, wrote, “The economic role of the gods found important expression in their function as protectors of honest business practices. Some deities openly combated opportunism (self-interest pursued with guile) and lowered transaction costs by actively inculcating and enforcing professional standards” (Silver Reference Silver1995, p. 5). The gods also concerned themselves with public morality more broadly. In ancient Egypt, “The two components of the general concept of religion, and at the same time the central functions of kingship, are (1) ethics and the dispensing of justice (the creation of solidarity and abundance in the social sphere through dispensing justice, care, and provisions) and (2) religion in the narrower sense, pacifying the gods and maintaining adequate contact with them, as well as provisioning the dead” (Assmann Reference Assmann2001, p. 5).

The so-called karmic religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism) also reflect historical convergences between religion and public morality, although the precise psychological mechanisms are not as well understood as for the Abrahamic religions. Obeyesekere (Reference Obeyesekere2002) observes that the notion of rebirth is present in many small-scale societies – but disconnected from morality. Gradually, rebirth connects with the idea of ethical causation across lifetimes, and begins to influence the cooperative sphere. In a seminal field study with modern Hindu samples, participation and observation of extreme Hindu rituals such as the Kavadi, practiced among devotees of the Tamil war god Murugan, increased prosocial behavior (Xygalatas et al. Reference Xygalatas, Mitkidis, Fischer, Reddish, Skewes, Geertz, Roepstorff and Bulbulia2013). A Hindu religious environment was also shown to induce greater prosocial behavior in a common resource pool game (Xygalatas Reference Xygalatas2013). Karmic religions are, therefore, also compatible with the prosocial religious elements in the present framework, although cultural evolution may be harnessing a somewhat different psychology, a question that is ripe for experimental research.

3.2.3. The “Axial Age.”

The “Axial Age” refers to the period between 800 and 200 BCE that marked the birth of “genuine” public morality, individuality, and interior spirituality (Jaspers Reference Jaspers and Bullock1953). Since Jaspers, a common view of the historical record has been that there is a vast cultural chasm between pre–Axial Age amoral religions – demanding mere external ritual observance from their adherents –and Axial Age moral religions, a view some in the cognitive science of religion (e.g., Baumard & Boyer Reference Baumard and Boyer2013) have echoed. This interpretation is historically questionable on several fronts. To begin with, it fails to recognize the gradual nature of cultural evolution: Chiefdoms and early states predating the Axial Age by thousands of years had anthropomorphized deities that intervened in social relations, although their moral scope and powers to punish and reward were substantially narrower and more tribal than those of later, Axial gods. This is also true in contemporary Fijian chiefdom societies, as we noted in section 3.1. More plausibly, then, there has been a coevolution of two gradual historical processes: the broadening of the gods' powers and their moral concern, and an expansion of the cooperative sphere.

Moreover, the sheer length of this supposedly crucial historical period should itself raise suspicions about its usefulness as an explanatory category. The transition to prosocial religions emerges at very different time periods in various parts of the globe. Islam, for example, is a classic example of what we are calling a prosocial religion, both in terms of its doctrinal and ritualistic features and its apparent role in forging the disparate, warring tribes in the Arabian Peninsula into a unified, world historical force. Islam did not get its start until the sixth century CE, a full 800 years after the close of the “Axial Age.”

Finally, there is ample historical evidence that elements of “pre–Axial Age” religions were supportive of public morality. In ancient Egyptian religion, for example, moral behavior was seen as part of Maat, the supernaturally grounded “right order” of the world. One of the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom, “Apology of the Creator God,” written between 2181 and 2055 BCE, includes a passage where said Creator God takes credit for having created morality – and laments that people seem disinclined to follow his moral mandates.Footnote 7 Similarly, Hammurabi's code, a Babylonian text from around 1772 BCE, is a well-preserved document of a divinely inspired moral system, capitalizing on fear of Marduk, patron god of Babylon, and the powers of Shamash, god of justice: “When (my god) Marduk had given me the mission to keep my people in order and make my country take the right road, I installed in this country justice and fairness in order to bring well-being to my people” (Bottéro Reference Bottéro2001, pp. 168; for more on moralizing Mesopotamian gods, see Bellah Reference Bellah2011, pp. 221–24).

There are important open questions that require deeper analysis, regarding both the ethnographic and historical records. In moving this debate forward, it is important to recognize two crucial points that flow from a cultural evolutionary analysis. One is that our hypotheses are probabilistic, which allows for multiple causal pathways, including the possibility that in some societies prosocial religions played a minor or no role, or that their role emerged late in the process. Two, the historical trajectories of Big Gods, let alone the suite of elements we call prosocial religions, are not an all-or-nothing phenomenon. There is room for transitional gods that are knowledgeable about certain domains but not others and morally concerned in some respects but not others. As we noted, chiefdoms, in both the ethnographic and the historical records, appear to fit this intermediate pattern, and they are implicated in the expansion of the social scale. Their gods are more powerful and moralizing than those of foragers, although not as full-fledged as the Big Gods of states and empires (Bellah Reference Bellah2011).

Overall, these ethnographic, historical, and archaeological patterns are consistent with the idea that the religious elements we have highlighted have spread over human history and have replaced many alternatives. We could have found no pattern, or the opposite pattern; for example, most hunter–gatherers might have had big, moralizing gods. Therefore, in this sense, an empirical test was passed, at least provisionally. However, none of this evidence establishes causality, or that any of our key religious elements can cause people to behave prosocially. At least some of these historical and ethnographic data are also consistent with the alternative hypothesis that bigger and more prosocial societies simply projected bigger and more prosocial gods in their own image, or that bigger gods hitched a ride along with other institutional forms. In the final section, we return to the issue and explore the merits of alternative scenarios, but, next, we turn to the issue of the direction of causality postulated in this theory and explore whether adherence to the religious elements discussed previously directly increased prosociality.

4. Religion and prosocial behavior: Psychological evidence

If certain religious elements can promote prosociality, then we should be able to study these effects using a variety of tools from the cognitive and social sciences. We review here both correlational and experimental evidence in light of the abovementioned hypotheses.

4.1. Correlating religious involvement and prosocial behavior

Several lines of evidence now link participation in world religions with prosociality. A large sociological survey literature shows that religious engagement is related to greater reports of charitable giving and voluntarism (e.g., Brooks Reference Brooks2006; Putnam & Campbell Reference Putnam and Campbell2010). However, these findings are mostly confined to the American context and are based on self-reports, limiting generalizability, and inferences to actual behavior.

To avoid the problems of self-report, several studies now show a linkage between prosocial religions and the predicted forms of prosociality using economic games. In an investigation spanning 15 societies from around the globe, including populations of foragers, pastoralists, and horticulturalists, Henrich et al. (Reference Henrich, Ensimger, McElreath, Barr, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Lesorogol, Marlowe, Tracer and Ziker2010a; Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010b) found an association between world religion (Christianity or Islam) and prosocial behavior in two well-known economic games, the Dictator and Ultimatum Games. Unlike other studies, this one specifically validated the idea that participation in religions with Big Gods, CREDs, and related practices elicits more prosocial behavior in anonymous contexts than does participation in local or traditional religions, controlling for a host of economic and demographic variables. Interestingly, results of this and follow-up studies suggest that commitment to Big Gods is most likely to matter when the situation contains no credible threat of “earthly punishment” in the form of third-party monitoring (Laurin et al. Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and Kay2012b). Those effects of participation in a world religion disappear when a secular third-party punisher is introduced.

Other behavioral studies have also found reliable associations between various indicators of religiosity and prosociality, albeit under limited conditions. A study employing a common-pool resource game, which allowed researchers to compare levels of cooperation between secular and religious kibbutzim in Israel, showed higher cooperation in the religious kibbutzim than in the secular ones; the effect was driven by highly religious men who engaged in daily and communal prayer and took the least amount of money from the common pool (Sosis & Ruffle Reference Sosis and Ruffle2003). Soler (Reference Soler2012) found similar cooperative effects of religious participation among members of an Afro-Brazilian religious group: Controlling for various sociodemographic variables, individuals who displayed higher levels of religious commitment behaved more generously in a public goods game and also reported more instances of provided and received cooperation within their religious community (for a similar finding in a Muslim sample in India, see Ahmed Reference Ahmed2009).

Although these studies are provocative, it should be noted that similar studies conducted with Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) samples (Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010b) have found that individual differences in religious commitment typically fail to predict prosocial behavior (e.g., Batson et al. Reference Batson, Schoenrade and Ventis1993; Randolph-Seng & Nielsen Reference Randolph-Seng and Nielsen2007; Shariff & Norenzayan Reference Shariff and Norenzayan2007). This inconsistency may arise from several factors, but one important consideration is that among groups with high trust levels toward secular institutions (the police, courts, governments) – such as the WEIRD students of so many studies – the effect of these institutions crowds out the influence of religion. In this sense, the strong secular mechanisms that have emerged recently in some societies can replace the functions of prosocial religions, an issue to which we return. Or, undergraduates may not have solidified their religious commitments. Either way, psychologists' narrow focus on WEIRD undergraduates may have caused them to miss these important moderating contexts.

In summary, behavioral studies have found associations between religious commitment and prosocial tendencies (for reviews, see Norenzayan & Shariff Reference Norenzayan and Shariff2008; Norenzayan et al. Reference Norenzayan, Henrich, Slingerland, Richerson and Christiansen2013), especially when secular institutions are weak, reputational concerns are heightened, and the targets of prosociality are in-group members (coreligionists). However, causal inference in these studies is limited by their reliance on correlational designs. If religious devotion is predictive of prosocial behavior in some contexts, then we cannot conclusively rule out the idea that having a prosocial disposition causes one to be religious – or that a third variable, such as dispositional empathy or guilt-proneness, causes both prosocial and religious tendencies. To address this issue, we consult a growing experimental literature that induces religious thinking and subsequently measures prosocial behavior.

4.2. Religious priming increases fairness, cooperation, and costly punishment while decreasing cheating

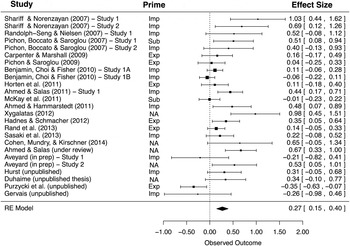

If religious beliefs have a causal effect on prosocial tendencies, then experimentally induced religious thoughts should increase prosocial behavior. Findings support this prediction. Religious reminders reduce cheating, curb selfish behavior, increase fairness toward strangers, and promote cooperation in anonymous settings for samples drawn from societies shaped by prosocial religions, primarily Abrahamic ones (for a recent review, see Norenzayan et al. Reference Norenzayan, Henrich, Slingerland, Richerson and Christiansen2013). Figure 2 shows the results of a recent meta-analysis (25 studies, 4,825 participants) from this literature (Shariff et al., Reference Shariff and Norenzayanin press), which shows that, overall, religious priming reliably increases prosocial behavior. The effect remains robust (though somewhat reduced) after estimating and adjusting for the prevalence of studies with null findings that are less likely to appear in the published literature.

Figure 2. A meta-analysis of religious priming studies shows that religious reminders increase prosocial behavior, with an average effect size of Hedges'g=0.27, 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.40 (from Shariff et al. Reference Shariff and Norenzayanin press, with permission from Sage). Error bars are 95% CI of effect sizes.Footnote 8

Crucially, analyses looking at religious priming effects on a broad range of psychological outcomes (93 studies and 11,653 participants) showed that these effects are moderated by prior religious belief. That is, religious priming effects are reliable for strong believers, but they vanish for nonbelievers (Shariff et al., Reference Shariff and Norenzayanin press). This suggests either that nonbelievers are not responsive to religious reminders, or that there is large variability among nonbelievers with regard to their responsiveness to religious primes. This is important, because it indicates that exogenous religious primes interact with endogenous religious beliefs. Religious priming is shaped by cultural conditioning, and it is not merely the result of low-level associations (in addition, it could be interpreted to mean that religious primes are most effective when they are self-relevant, as is often the case in the priming literature, e.g., Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, DeMarree and Petty2007).

The experimental and correlational literatures also reveal several important points about the psychological mechanisms involved.

-

1. Supernatural punishment and supernatural benevolence have divergent effects on prosocial behavior. In laboratory experiments, greater belief that God is punishing is more strongly associated with reductions in moral transgressions such as cheating, whereas greater belief that God is benevolent, if anything, has the opposite effect, increasing cheating (Shariff & Norenzayan Reference Shariff and Norenzayan2011). Similarly, at the national level, greater belief in hell relative to heaven is predictive of lower national crime rates such as burglary, holding constant a wide range of socioeconomic factors and the dominant religious denomination (Shariff & Rhemtulla Reference Shariff and Rhemtulla2012).

-

2. Gods are believed to monitor norm violations. Reaction time analyses suggest that believers intuit that God has knowledge about norm-violating behaviors more than they believe that God has knowledge about other behaviors (Purzycki et al. Reference Purzycki, Finkel, Shaver, Wales, Cohen and Sosis2012).

-

3. Religious priming increases believers' perceptions of being under social surveillance (Gervais & Norenzayan Reference Gervais and Norenzayan2012a).

-

4. Belief in a punishing god is associated with less punishing behavior toward free-riders, because participants believe that they can offload punishing duties to God (Laurin et al. Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and Kay2012b). Here, people are doing the opposite of what they think God is doing.

Together, these findings suggest a role linking beliefs in morally concerned, punitive, supernatural monitors to increases in prosocial behavior. These findings contradict the idea that already prosocial individuals spontaneously imagine conceptions of prosocial deities, or with explanations that suggest that religious priming brings to mind cultural stereotypes linking religion with benevolence, which in turn encourage benevolent behaviors such as generosity (Norenzayan et al. Reference Norenzayan, Henrich, Slingerland, Richerson and Christiansen2013). Finally, our framework predicts cultural variability in religious priming; these effects should diminish in cultural contexts, typically in smaller-scale groups, where religious elements and norm compliance are largely disconnected, and the gods have limited omniscience and are morally indifferent. This hypothesis remains open to investigation.

4.3. Prosocial religions encourage self-control

Participation in prosocial religions cultivates a variety of self-regulatory mechanisms, including self-control, goal pursuit, and self-monitoring: all processes that may also partly explain religion's capacity to suppress selfishness in the interest of the group and promote longevity and health (McCullough & Willoughby Reference McCullough and Willoughby2009). Although most of the supporting evidence is correlational (e.g., Carter et al. Reference Carter, McCullough, Kim-Spoon, Corrales and Blake2012), recent experimental studies suggest a causal direction. In a series of experiments (Rounding et al. Reference Rounding, Lee, Jacobson and Ji2012; see also Laurin et al. Reference Laurin, Kay and Fitzsimons2012a), religious primes were found to increase an individual's willingness to endure unpleasant experiences (e.g., drinking juice mixed with vinegar) and delay gratification (e.g., by agreeing to wait for a week to receive $6 instead of being paid $5 immediately). In addition, religious reminders increased persistence on a difficult task when self-control resources were depleted (Rounding et al. Reference Rounding, Lee, Jacobson and Ji2012). Other experimental findings (e.g., Inzlicht & Tullett Reference Inzlicht and Tullett2010) corroborate these observations, showing that implicit religious reminders enhance the exercising of self-control processes, by, for example, suppressing neurophysiological responses to cognitive error. Self-control is closely related to prosociality, because cooperating or complying with various norms often requires forgoing immediate returns in exchange for some future benefits, group benefits, or afterlife rewards.

Many ritual and devotional practices may have culturally evolved in part by increasing self-control (see below) and performance. For example, Legare and Souza (Reference Legare and Souza2012; Reference Legare and Souza2014) have explored how the elements found in widespread rituals, including repetitions, multiple-step complexity, and supernatural connections, tap aspects of our intuitive causal cognition to increase their perceived efficacy. Believing one is equipped with efficacious rituals may foster self-regulation, persistence, and discipline by increasing individuals' confidence in their own success. Ritually enhanced self-efficacy improves performance (Damisch et al. Reference Damisch, Stoberock and Mussweiler2010).

5. Galvanizing group solidarity

Belief-ritual complexes take shape as cultural evolution increasingly exploits a variety of psychological mechanisms to ratchet up internal harmony, cooperation, and social cohesion. In this way, prosocial religions bind anonymous individuals into moral communities (Graham & Haidt Reference Graham and Haidt2010; Haidt & Kesebir Reference Haidt, Kesebir, Fiske and Gilbert2010), without prosocial religious elements being necessary for moral capacities or vice versa (Norenzayan Reference Norenzayan2014). Although many important open questions remain, here we focus on several that appear critical and that have received some attention.

5.1. Transmitting commitment: Why extravagant displays deepen faith and promote solidarity

The extravagance of some religious rituals has long puzzled evolutionary scientists. These performances demand sacrifices of time, effort, and resources. They include rites of terror, various restrictions on behavior (sex, poverty vows), painful initiations (tattooing, walking on hot stones), diet (fasts and food taboos), and lifestyle restrictions (strict marriage rules, dress codes). Why are extravagant displays of faith commonly found in prosocial religions?

The answer to this question could be found in the way that cultural learning biases operate. Belief can be easily faked, which would allow cultural models to manipulate learners by propagating “beliefs” that they did not sincerely hold. One evolutionary solution to this dilemma is for cultural learners to be biased toward acquiring beliefs that are backed up by deeds that would not be performed if the model's beliefs were not genuine (as well as related strategies for “epistemic vigilance,” see Sperber et al. Reference Sperber, Clément, Heintz, Mascaro, Mercier, Origgi and Wilson2010). Although limited, existing experimental work on cultural learning indicates that CREDs play an important role in the transmission of belief or commitment in multiple domains where cultural influence matters, not just in religious contexts (for review see Henrich Reference Henrich2009; for more recent evidence, see Lanman Reference Lanman2012; Willard et al. Reference Willard, Norenzayan and Henrich2015). In prosocial religions, CREDs are of particular importance, given that faith spreads by cultural influence, and that religious hypocrites can undermine group cohesion. The idea here is that cultural evolution exploited the evolved inclination to attend to CREDs as a mechanism to deepen religious faith and commitment, and thereby promote cooperation.

Religious displays of self-sacrifice are often seen in influential religious leaders, who then transmit these beliefs to their followers. For example, when male priests of the Phrygian goddess Cybele performed ritualized public self-castrations, they sparked cultural epidemics of Cybele religious revival in the early Roman Empire that often competed with the spread of Christianity (Burkert Reference Burkert1982). Similarly, early Christian saints, by their willing martyrdom, became potent models that encouraged the cultural spread of Christian beliefs (Stark Reference Stark1996). When religious leaders' actions credibly communicate their underlying belief and commitments, their actions in turn energize witnesses and help their beliefs to spread in a group, after which commitment deepens. If, on the other hand, they are not willing to make a significant demonstration of their commitment, then observers – even children – withhold their own commitment to those beliefs. Supporting this idea, Lanman (Reference Lanman2012) reports that in Scandinavia children are less likely to adopt the beliefs of their religious parents if those parents do not display religious CREDs. Conversely, both children and adults, exposed to both religious propositions (implicit or explicit) and CREDs, acquire a deeper commitment or belief in them than they would otherwise.

Once people believe, they are more likely to perform similar displays themselves, which offers another explanation of why extravagant behaviors are culturally infectious in prosocial religious groups. Moreover, CREDs often come in the form of altruistic giving to other in-group members, further ratcheting up the level of in-group cooperation in prosocial religious groups. For example, Xygalatas et al. (Reference Xygalatas, Mitkidis, Fischer, Reddish, Skewes, Geertz, Roepstorff and Bulbulia2013) investigated the prosocial effects of participation in, and witnessing of, the Kavadi, an extreme set of devotional rituals for Murugan, the Tamil god of war, among Hindus in Mauritius. The act of witnessing this intense, pain-inducing set of rituals increased anonymous donations to the temple as much as participating did. Donation sizes correlated with perceptions of the pain involved. This suggests that extreme ritual worship such as this one is likely to be a CRED-like phenomenon in addition to any signaling functions that it carries.

Although reliance on CREDs evolved for adaptive reasons originally unrelated to religion, their exploitation by prosocial religions helps explain why (1) religious participants, and especially religious leaders, must engage in sacrifices (e.g., vows of poverty and chastity make leaders more effective transmitters of faith and commitment); (2) martyrdom emerges prominently in religious narratives and actions; and (3) Big Gods are believed to demand extravagant sacrifices and worship, thereby causing CREDs, which in turn deepen faith in these Big Gods.

Finally, cultural evolution may have shaped the rituals of prosocial religions for the effective transmission of standardized religious beliefs and doctrines across large populations. Following Whitehouse's formulation (2004), we propose that cultural evolution may have increasingly favored the “doctrinal mode” of ritual, in which some subset of rituals becomes high frequency, low arousal, highly repetitious, and obligatory. The idea is that these types of repetitious rituals may cue norm psychology and increase the transmission fidelity of certain religious ideas (Herrmann et al. Reference Herrmann, Legare, Harris and Whitehouse2013; Kenward et al. Reference Kenward, Karlsson and Persson2010), thereby helping to maintain religious uniformity in large populations, not only among those individuals attending the ritual (more on this subsequently), but also across a larger imagined community of coreligionists.

5.2. Synchrony and fictive kinship

Prosocial religions often harness collective rituals that are characterized by shared, synchronous arousal, a phenomenon Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1915) termed collective effervescence. Historians have suggested that this synchronous arousal was the key to understanding the military innovation of close-order drill, which increased unit solidarity (McNeill Reference McNeill1982; Reference McNeill1995). Recent empirical work shows that the experience of synchrony increases feelings of affiliation (Hove & Risen Reference Hove and Risen2009; also see Paladino et al. Reference Paladino, Mazzurega, Pavani and Schubert2010; Valdesolo et al. Reference Valdesolo, Ouyang and DeSteno2010) and facilitates feelings of fusion with the group, which may in turn encourage acts of sacrifice for the group (Swann et al. Reference Swann, Gomez, Seyle, Morales and Huici2009). One study found that joint music-making promotes prosocial behavior even among 4-year-olds (Kirschner & Tomasello Reference Kirschner and Tomasello2010). Experimental work has also shown that participation in synchronous song and dance results in greater trust, greater feelings of “being on the same team,” and more cooperation in economic games (Wiltermuth & Heath Reference Wiltermuth and Heath2009). Even witnessing fire-walking puts the heart-rate rhythms of friends and relatives in sync with those of the walkers (Konvalinka et al. Reference Konvalinka, Xygalatas, Bulbulia, Schjoedt, Jegindo and Wallot2011). As noted earlier, synchronous rituals may also affect self-regulation: Rowing synchronously with team members leads to higher levels of pain tolerance (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Ejsmond-Frey, Knight and Dunbar2010), which should improve team performance.

Many have observed that the prosocial religious groups that often unite people across ethnic, linguistic, and geographic boundaries evoke kinship in referring to each other (Atran & Henrich Reference Atran and Henrich2010; Nesse Reference Nesse1999). Christians often describe themselves as belonging to a “brotherhood,” a common term that often applies today to the global fraternity (ikhwan) of Islam (Atran & Norenzayan Reference Atran and Norenzayan2004). In fifth-century BCE China, Confucius famously observed that anyone in the world sharing his moral and religious commitments should be viewed as a “brother” (Analects 12.5; Slingerland Reference Slingerland2003, p. 127), and throughout Chinese imperial history the emperor was known as the “Son of Heaven” and viewed as the both the mother and father of the populace.