1. Introduction

When jolted by a rough skydiving landing, psychologist James Easterbrook observed that his sense of space and time shrank and slowly re-expanded (Easterbrook Reference Easterbrook1982). This sparked his curiosity about how arousal influences attention. Later he published a review article in which he argued that under arousal, people rely more on central or immediately relevant information and less on peripheral information (Easterbrook Reference Easterbrook1959). Since his seminal paper, researchers have accumulated many more observations that arousal evoked by emotional events enhances some aspects of perception and memory but impairs others (for reviews, see Mather & Sutherland Reference Mather and Sutherland2011; Reisberg & Heuer Reference Reisberg, Heuer, Reisberg and Hertel2004). For example, victims of a crime tend to remember the weapon vividly but forget the perpetrator's face (Steblay Reference Steblay1992). People also pay attention to emotional information at the expense of neutral information (Dolcos & McCarthy Reference Dolcos and McCarthy2006; Knight et al. Reference Knight, Seymour, Gaunt, Baker, Nesmith and Mather2007). These examples fit with Easterbrook's formulation that arousal impairs attention to peripheral information. But arousing stimuli can sometimes enhance memory of peripheral neutral information (Kensinger et al. Reference Kensinger, Garoff-Eaton and Schacter2007; Knight & Mather Reference Knight and Mather2009). Thus, although it is clear that arousal shapes attention and memory, knowing that something is neutral or spatially peripheral is not enough to predict how it will fare under emotional conditions.

So, then, how does arousal influence the brain's selection of features to highlight versus suppress? An initial answer to this puzzle was provided by the arousal-biased competition (ABC) model, which posits that arousal does not have fixed rules about which types of stimuli to enhance or suppress. Instead, arousal amplifies the stakes of ongoing selection processes, leading to “winner-take-more” and “loser-take-less” effects in perception and memory (Mather & Sutherland Reference Mather and Sutherland2011). The ABC model builds on biased competition models proposing that stimuli must compete for limited mental resources (Beck & Kastner Reference Beck and Kastner2009; Desimone & Duncan Reference Desimone and Duncan1995; Duncan Reference Duncan2006). As conceptualized by Desimone and Duncan (Reference Desimone and Duncan1995), both bottom-up and top-down neural mechanisms help resolve competition.

Bottom-up processes are largely automatic, determined by the perceptual properties of a stimulus, and do not depend on top-down attention or task demands. For example, stimuli that contrast with their surroundings, such as a bright light in a dark room, engage attention automatically even if they are currently goal irrelevant (Itti & Koch Reference Itti and Koch2000; Parkhurst et al. Reference Parkhurst, Law and Niebur2002; Reynolds & Desimone Reference Reynolds and Desimone2003). Top-down goals can also bias competition in favor of particular stimuli that otherwise would not stand out. Although not included in the original biased competition models, past history with particular stimuli is also a source of selection bias (Awh et al. Reference Awh, Belopolsky and Theeuwes2012; Hutchinson & Turk-Browne Reference Hutchinson and Turk-Browne2012). For example, one's name or a novel stimulus tends to engage attention (Moray Reference Moray1959; Reicher et al. Reference Reicher, Snyder and Richards1976). In addition, faces, text, and emotionally salient stimuli all grab attention (e.g., Cerf et al. Reference Cerf, Frady and Koch2009; Knight et al. Reference Knight, Seymour, Gaunt, Baker, Nesmith and Mather2007; MacKay et al. Reference MacKay, Shafto, Taylor, Marian, Abrams and Dyer2004; Niu et al. Reference Niu, Todd and Anderson2012).

A core aspect of most current theories of visual attention is that these different signals are integrated into maps of the environment that indicate the priority or salience of stimuli across different locations (Itti & Koch Reference Itti and Koch2000; Soltani & Koch Reference Soltani and Koch2010; Treisman Reference Treisman1998). Regions in frontoparietal cortex integrating sensory and top-down signals help represent such priority maps (Ptak Reference Ptak2012). Moreover, having both feedforward and feedback connections between sensory regions and cortical priority maps enables distributed representations of prioritized information to modulate their own processing (e.g., lower-level visual features) even further (Klink et al. Reference Klink, Jentgens and Lorteije2014; Ptak Reference Ptak2012; Serences & Yantis Reference Serences and Yantis2007; Soltani & Koch Reference Soltani and Koch2010). Thus, priority signals are self-biasing to enhance efficient information processing in the brain.

In the ABC model, arousal further biases mental processing to favor high- over low-priority representations, regardless of whether initial priority is determined by bottom-up salience, emotional salience, or top-down goals. Thus, because spatially peripheral information is usually lower priority than central information, arousal usually impairs memory for it (Steblay Reference Steblay1992; Waring & Kensinger Reference Waring and Kensinger2011). Yet, when peripheral information is perceptually salient or goal relevant, arousal instead enhances memory for it (e.g., Kensinger et al. Reference Kensinger, Garoff-Eaton and Schacter2007, Experiment 4). But the ABC model does not tackle how this works in the brain. Previous brain-based models of emotion and cognition also do not account for the dual role of arousal. Most models posit that the amygdala enhances perception and memory consolidation of emotionally salient stimuli, but fail to address how arousal sometimes enhances and sometimes impairs information processing.

In this article we propose the glutamate amplifies noradrenergic effects (GANE) model, in which arousal amplifies the activation difference between high- and low-priority representations via local synaptic self-regulation of the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine (LC–NE) system. According to the GANE model, hearing an alarming sound or seeing something exciting leads to a surge in NE release, which, in turn, enhances activity of neurons transmitting high-priority mental representations and suppresses activity of neurons transmitting lower-priority mental representations. As already outlined, priority is determined by top-down goals, bottom-up factors, and high-level stimulus features (Beck & Kastner Reference Beck and Kastner2009; Desimone & Duncan Reference Desimone and Duncan1995; Fecteau & Munoz Reference Fecteau and Munoz2006).

According to the GANE model, the brain's primary excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, signals priority. Under arousal, elevated glutamate associated with highly active neural representations stimulates greater NE release, which then further increases glutamate via positive feedback loops. Thus, in these local “NE hotspots,” glutamate signals are amplified. At the same time, wherever NE is released and fails to ignite a local hotspot, inhibitory adrenoreceptors with lower thresholds of activation suppress activity. Higher NE concentration at hotspots also enhances delivery of energy resources to the site of active cognition, synchronizes brain oscillations, and modulates activity in large-scale functional networks. Thus, under arousal, local NE hotspots contrast with widespread NE suppression to amplify priority effects in perception and memory, regardless of how priority was instantiated.

2. Arousal-biased competition in perception and memory

We start by reviewing recent findings supporting Mather and Sutherland's (Reference Mather and Sutherland2011) ABC model and its novel predictions. Next, we turn to the question of how these arousal effects operate in the brain. A fundamental challenge in understanding how arousal influences cognition is that it sometimes enhances and sometimes impairs information processing. Although most emotion research focuses on how processing of emotional stimuli is enhanced compared with neutral stimuli, emotional arousal can also influence processing of neutral stimuli, and across studies, opposing effects are often seen. How can emotionally salient stimuli sometimes enhance memory for what just happened, but other times impair it? When do arousing stimuli enhance perception and when do they impair perception of subsequent stimuli? Many studies report that emotion increases selectivity (for reviews, see Levine & Edelstein Reference Levine and Edelstein2009; Mather & Sutherland Reference Mather and Sutherland2011; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Holland, Kensinger, Robinson, Watkins and Harmon-Jones2013), but how do we predict what gets selected?

2.1. Arousal enhances perception of salient stimuli, but impairs perception of inconspicuous stimuli

In previous research on how arousal influences subsequent perception, two types of findings were hard to reconcile. First, arousing stimuli impair perception of subsequent stimuli. For example, people preferentially perceive arousing stimuli (e.g., Anderson Reference Anderson2005; Keil & Ihssen Reference Keil and Ihssen2004) but fail to perceive or encode neutral stimuli close to arousing stimuli either in time (e.g., embedded in a rapid series of images after an arousing image) (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Most, Newsome and Zald2006) or in space (Kensinger et al. Reference Kensinger, Garoff-Eaton and Schacter2007; Tooley et al. Reference Tooley, Brigham, Maass and Bothwell1987). Second, hearing or seeing an arousing stimulus enhances visual perception of a subsequent Gabor patch (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Baek, Lu and Mather2014a; Padmala & Pessoa Reference Padmala and Pessoa2008; Phelps et al. Reference Phelps, Ling and Carrasco2006).

How can we explain both the enhancing and impairing effects of arousing stimuli on perception of stimuli that appear close in time or space? Initial evidence supports the ABC hypothesis that inducing arousal should have two opposing effects on perception: Arousal should enhance processing of high-priority (more salient) stimuli but impair processing of lower-priority (less salient) stimuli. When asked to report as many letters as they could from a briefly flashed array (Fig. 1), participants reported more of the high-salience letters and fewer of the low-salience letters after hearing an arousing emotionally negative sound than after hearing a neutral sound (Sutherland & Mather Reference Sutherland and Mather2012). Similar results were obtained when arousal was induced by emotionally positive sounds (Sutherland & Mather, under review). These results indicate that arousal makes salient stimuli stand out more than they would otherwise.

Figure 1. Participants heard an arousing or neutral sound before a letter array was flashed briefly. They then reported as many of the letters as they could. Some of the letters were shown in dark gray (high contrast and, therefore, salient) and some in light gray (low contrast and less salient). Participants reported a greater proportion of the salient letters than the nonsalient letters, but this advantage for salient letters was significantly greater on arousing trials than on neutral trials, and the disadvantage for the nonsalient letters was significantly greater on arousing than on neutral trials (Sutherland & Mather Reference Sutherland and Mather2012).

The ABC model also explains the enhanced processing of emotional stimuli, the focus of most previous theoretical accounts (e.g., Kensinger Reference Kensinger2004; LaBar & Cabeza Reference LaBar and Cabeza2006; Mather Reference Mather2007; Murty et al. Reference Murty, Ritchey, Adcock and LaBar2010; Phelps Reference Phelps2004). People tend to prioritize emotional stimuli due to top-down goals (e.g., increasing pleasure and avoiding pain), their emotional saliency (e.g., associations with reward/punishment), and/or bottom-up salience (e.g., a gunshot is loud as well as a threat to safety [Markovic et al. Reference Markovic, Anderson and Todd2014]). Thus, arousing stimuli should dominate competition for representation at their particular spatiotemporal position (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Kennedy and Most2012).

If the arousing stimulus appears in the exact same location as a neutral stimulus presented less than a second later, it will impair perception of that neutral stimulus, an effect known as emotion-induced blindness (Kennedy & Most Reference Kennedy and Most2012; Most et al. Reference Most, Chun, Widders and Zald2005). On the other hand, arousing stimuli tend to enhance the dominance of high-priority stimuli that are nearby but not competing for the same spatiotemporal spot. An emotionally salient word that impairs perception of a subsequent target word flashed in the same location 50 or 500 ms later can instead enhance perception of a target word flashed 1,000 ms later (Bocanegra & Zeelenberg Reference Bocanegra and Zeelenberg2009), because after the longer interval, the priority of the target word is no longer overshadowed by the emotionally salient word.

2.2. Arousal enhances perceptual learning about salient stimuli but impairs learning about nonsalient stimuli

Interspersing emotional or neutral pictures with a visual search task had opposite effects on perceptual learning of salient and nonsalient targets (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Itti and Mather2012). In this study, the targets were always the same, but in one condition they were salient because they differed from the distractors, and in the other condition they were not salient because they were quite similar to distractors. Emotional images enhanced perceptual learning about the salient target lines but impaired learning of nonsalient targets (Fig. 2). Thus, whether arousal enhanced or impaired learning depended on the target's salience.

Figure 2. Estimated tuning curves for averaged “target” responses as a function of emotion in the high-salience condition (A) and low-salience condition (B). In the high-salience condition, having interspersed emotional pictures enhanced perceptual learning of the exact tilt of the target (55°), whereas in the low-salience condition, emotion impaired learning of the exact tilt of the same target. Figure adapted from Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Itti and Mather2012).

2.3. How arousal modulates neural representations depends on salience

A recent study took advantage of the fact that faces and scenes activate distinct representational regions in the brain to test the ABC hypothesis that arousal increases brain activation associated with processing of salient stimuli, whereas it decreases brain activation associated with processing of less salient stimuli (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Sakaki, Cheng, Velasco and Mather2014b). On each trial, one yellow-framed face and one scene image appeared briefly side-by-side and then a dot appeared in the former location of one of the images (Fig. 3A). The participants' task was to indicate the side on which the dot appeared. Participants responded fastest to dots that appeared behind the salient faces on trials preceded by a tone conditioned to predict shock and thereby induce arousal. In a follow-up functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study, there was an arousal×saliency interaction in visual category-specific brain regions, such that arousal enhanced brain activation in the region processing the salient stimulus (i.e., fusiform face area) but suppressed brain activation in the region processing the nonsalient stimulus (i.e., parahippocampal place area) (Fig. 3B) (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Sakaki, Cheng, Velasco and Mather2014b).

Figure 3. In the functional magnetic resonance imaging study by Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Sakaki, Cheng, Velasco and Mather2014b), tones conditioned to predict shock (CS+ tones) played before the display of a salient face, and a less salient scene (A) increased activity in the left fusiform face area (FFA) associated with face processing, while decreasing activity in the left parahippocampal place area (PPA) associated with scene processing, compared with tones conditioned not to predict shock (CS– tones) (B). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005. CS = conditioned stimulus; ISI = interstimulus interval.

2.4. Arousal enhances or impairs memory consolidation of representations depending on their priority

So far, we have focused on how arousal enhances processing of subsequent inputs; however, arousal should have similar effects on mental representations currently active at the moment arousal is induced. Previous research has indicated that arousal induced after initial encoding sometimes impairs and sometimes enhances memory of preceding information (Knight & Mather Reference Knight and Mather2009). The critical ABC hypothesis is that experimental manipulation of priority of information should alter the effect of subsequent arousal on memory consolidation.

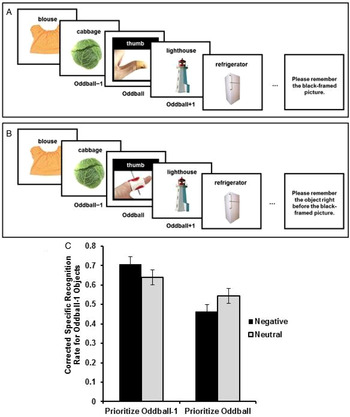

In the first study testing this hypothesis, participants viewed lists of objects one object at a time, with one perceptual oddball in each list (Fig. 4) (Sakaki et al. Reference Sakaki, Fryer and Mather2014a). The oddball was either emotionally salient or neutral. Some participants were asked to recall the name of the oddball picture as soon as the list presentation ended. In this condition, the object shown just before the oddball (e.g., the cabbage in Fig. 4) was low priority. Other participants were asked to recall the name of the object shown just before the oddball (oddball-minus-1 object). Thus, in this condition, the oddball-minus-1 object (e.g., the cabbage) was high priority. After a series of lists, memory for details of all oddball-minus-1 objects was tested. As predicted, positively or negatively emotionally salient oddball pictures enhanced memory for prioritized oddball-minus-1 objects and impaired memory for nonprioritized oddball-minus-1 objects.

Figure 4. Schematic representations of a neutral trial in the prioritize-oddball condition (A) and a negative trial in the prioritize-oddball-minus-1 condition (B). Memory performance for oddball-minus-1 objects differed as a function of their priority and the valence of oddball pictures (C). Oddball pictures depicted here were obtained from iStockPhoto for illustration purposes and differ from those used in the experiments. Figures from Sakaki et al. (Reference Sakaki, Fryer and Mather2014a).

Although the brain mechanisms underlying this priority×arousal interaction in memory have yet to be tested, fMRI evidence indicates that arousal enhances activity in regions processing a high-priority stimulus. For example, pairing shock with certain high-priority (i.e., standalone) neutral scenes enhances successful encoding-related activity in the parahippocampal place area (PPA), the brain region specialized to process scene information (Schwarze et al. Reference Schwarze, Bingel and Sommer2012). Thus, arousal-induced enhancement of brain activity processing prioritized information not only occurs during perception (e.g., Lee et al. Reference Lee, Sakaki, Cheng, Velasco and Mather2014b), but also predicts memory for such items.

2.5. Summary

Mather and Sutherland's (Reference Mather and Sutherland2011) ABC model accounts for both the enhancement and impairment effects of arousal on neutral stimuli across a wide variety of experimental contexts. It makes novel predictions: (1) Arousal before exposure to stimuli should amplify the effects of salience on perception and memory encoding; and (2) Arousal shortly after encoding information should amplify the effects of its goal relevance on memory consolidation. Both effects result from arousal's differential modulation of representations depending on priority. Other models also highlight the importance of interactions between arousal, attention, and goals (Kaplan et al. Reference Kaplan, Van Damme and Levine2012; Levine & Edelstein Reference Levine and Edelstein2009; Montagrin et al. Reference Montagrin, Brosch and Sander2013; Talmi Reference Talmi2013). However, so far there has been no account of how arousal amplifies the effects of priority in the brain.

3. Current brain-based models of arousal's modulatory effects

Before we present our account of how arousal can modulate neural representations differently depending on their priority, we outline how existing brain-based models of arousal and cognition fail to adequately address how arousal has opposite effects depending on representational priority (see Table 1 for an overview).

Table 1. Brain-based emotion-cognition theories.

3.1. Modular vs. “multiple waves” of emotion enhancement in perception

Noticing things like snakes and guns can increase the odds of survival. Consistent with this adaptive importance, emotionally salient stimuli are often detected more rapidly than neutral stimuli (Leclerc & Kensinger Reference Leclerc and Kensinger2008; Mather & Knight Reference Mather and Knight2006; Öhman et al. Reference Öhman, Flykt and Esteves2001). Explaining the privileged status of emotional stimuli has been the focus of brain models of emotion perception. One common assumption is that the evolutionary value of noticing emotional stimuli led to a specialized emotion module or pathway to evaluate emotional salience (Tamietto & de Gelder Reference Tamietto and de Gelder2010). For example, in their multiple attention gain control (MAGiC) model, Pourtois et al. (Reference Pourtois, Schettino and Vuilleumier2013) argue that emotional salience shapes perception via amplification mechanisms independent of other attentional processes. In the MAGiC model, the amygdala and other modulatory brain regions amplify neural responses to emotional relative to neutral stimuli along sensory pathways. The model also posits that these modulations occur parallel to and sometimes in competition with signals from bottom-up (exogenous) and top-down (endogenous) attentional control systems (see also Vuilleumier Reference Vuilleumier2005b).

In contrast, Pessoa and Adolphs (Reference Pessoa and Adolphs2010) argue against a modular approach to emotion enhancement in perception. In their multiple waves model, affectively and motivationally significant visual stimuli rapidly engage multiple brain sites, including the amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior insula, and anterior cingulate cortex, that then bias processing to favor these stimuli. From their perspective, the amygdala helps prioritize emotional aspects of information processing by coordinating activity in other regions involved in selective attention. Thus, in the multiple waves model, emotion influences general-purpose perceptual and attention systems rather than harnessing independent brain mechanisms to enhance perception of emotional items.

The latter perspective is more compatible with our findings than are separate-system models; if emotional stimuli were processed via a system separate from that processing neutral stimuli, it is not clear how emotional arousal could have both enhancing and impairing effects on neutral stimuli depending on their priority. However, even this modulatory multiple waves approach to emotion–cognition interactions fails to explain the full picture of how emotional arousal influences cognitive processing, as it focuses only on the enhanced perception of arousing stimuli and ignores how arousal affects perceptual selectivity more generally.

3.2. Canonical amygdala modulation model of emotional memory enhancement

The act of noticing something creates initial trace representations that require additional resources over the next few minutes, hours, and days to consolidate into a longer-lasting memory. Much research indicates that emotional arousal experienced before, during, or after an event can enhance these memory consolidation processes (Hermans et al. Reference Hermans, Battaglia, Atsak, de Voogd, Fernández and Roozendaal2014). The prevailing view of how emotion affects memory consolidation is that the amygdala enhances processes in the hippocampus and other memory-related brain regions in the medial temporal lobes, such that memory for emotional events is enhanced compared with memory for neutral events (e.g., McGaugh Reference McGaugh2004). Consistent with this idea, activity in the amygdala during encoding predicts later memory for emotional items, but not memory for neutral items, as does greater amygdala functional connectivity with medial temporal brain regions (Dolcos et al. Reference Dolcos, LaBar and Cabeza2004; Kilpatrick & Cahill Reference Kilpatrick and Cahill2003; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Strange and Dolan2004; Ritchey et al. Reference Ritchey, Dolcos and Cabeza2008).

Converging rodent and human research indicates that NE facilitates the amygdala-mediated enhancement of emotional information. For example, NE released in the amygdala during arousal is associated with enhanced memory for the emotionally arousing event (McIntyre et al. Reference McIntyre, Hatfield and McGaugh2002). Infusion of noradrenergic agonists into the basolateral amygdala after training also enhances memory for emotionally arousing events (Hatfield & McGaugh Reference Hatfield and McGaugh1999; LaLumiere et al. Reference LaLumiere, Buen and McGaugh2003). In humans, administration of the β-adrenergic antagonist propranolol impairs emotional memories, whereas pharmacological agents that increase NE levels, such as a selective NE reuptake inhibitor, tend to enhance them (Chamberlain & Robbins Reference Chamberlain and Robbins2013), and enhanced amygdala activity during encoding emotional stimuli is reduced by propranolol (Strange & Dolan Reference Strange and Dolan2004). Thus, NE–amygdala interactions enhance memory for emotional events.

Activation of the amygdala by NE can also impair memory for neutral information encountered near something emotional. For example, as already described earlier in the context of the Sakaki et al. (Reference Sakaki, Fryer and Mather2014a) study, people often have worse memory for neutral-low priority information shown immediately before an emotional compared with a neutral “oddball” stimulus. Patients with amygdalar damage do not exhibit decrements in memory for neutral words preceding emotional oddball words, and in normal individuals, a β-adrenergic antagonist prevents this retrograde memory impairment (Strange et al. Reference Strange, Hurlemann and Dolan2003).

Although not usually articulated, the amygdala modulation hypothesis presumably explains these impairment effects for neutral stimuli in terms of a trade-off in which the amygdala focuses resources on emotional stimuli, leaving fewer resources available to process and consolidate the neutral stimuli. However, this trade-off explanation fails to explain how NE–amygdala interactions can also enhance memory for nonarousing information (e.g., Barsegyan et al. Reference Barsegyan, McGaugh and Roozendaal2014; Roozendaal et al. Reference Roozendaal, Castello, Vedana, Barsegyan and McGaugh2008).

3.3. Biased attention via norepinephrine model

In the biased attention via norepinephrine (BANE) model, Markovic et al. (Reference Markovic, Anderson and Todd2014) propose that affectively salient stimuli activate the LC–NE system to optimize their own processing. Like the ABC model (Mather & Sutherland Reference Mather and Sutherland2011), the BANE model builds on biased competition models of attention (Markovic et al. Reference Markovic, Anderson and Todd2014). The BANE model proposes that affect-biased attention “is distinct from both ‘classic’ executive top-down and bottom-up visual attention and is at least in part circumscribed by a different set of neural mechanisms” (Markovic et al. Reference Markovic, Anderson and Todd2014, p. 230). In the BANE model, emotional salience is detected by an “anterior affective system,” including the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex, based on the recent history of reward and punishment. In turn, the amygdala's recruitment of the LC–NE system serves as an additional specialized pathway that further biases attention and memory in favor of the affectively relevant information that triggered NE release. However, like other models of emotion and cognition, the BANE model focuses exclusively on how affectively salient stimuli outcompete less salient stimuli and does not address how arousal induced by these stimuli sometimes enhances and sometimes impairs processing of proximal neutral information.

3.4. Emotional attention competes with executive attention for limited mental resources

Another line of work focuses on how emotional stimuli compete for executive resources (Bishop Reference Bishop2007; Choi et al. Reference Choi, Padmala and Pessoa2012; Eysenck et al. Reference Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos and Calvo2007), with some researchers positing that a ventral affective system competes with a dorsal executive system (Bush et al. Reference Bush, Luu and Posner2000; Dolcos et al. Reference Dolcos, Iordan and Dolcos2011). For example, when task-irrelevant emotional stimuli capture attention, they diminish dorsal executive brain region function and therefore disrupt working memory for neutral faces that were just seen (Dolcos & McCarthy Reference Dolcos and McCarthy2006; Dolcos et al. Reference Dolcos, Diaz-Granados, Wang and McCarthy2008). However, meta-analyses indicate that emotional responses are associated with both the ventral and dorsal prefrontal cortical regions (Phan et al. Reference Phan, Wager, Taylor and Liberzon2002; Shackman et al. Reference Shackman, Salomons, Slagter, Fox, Winter and Davidson2011), and so the notion that emotional distractors lead the ventral prefrontal cortical region to inhibit the dorsolateral prefrontal cortical region (Dolcos et al. Reference Dolcos, Diaz-Granados, Wang and McCarthy2008) is unlikely to be universal across different contexts.

Instead of a ventral/dorsal antagonism model, the dual competition model posits that emotional stimuli compete for resources at both perceptual and executive levels of processing (Pessoa Reference Pessoa2009; Reference Pessoa2013). For example, when participants heard tones predicting shock, regions within the frontoparietal network were activated (Lim et al. Reference Lim, Padmala and Pessoa2009). Recruitment of these regions during intense emotional arousal should make them less available for concurrent neutral task-related processing and lead to behavioral impairments. At the perceptual level of the dual competition model, both cortical and subcortical structures help amplify visual cortex responses to emotional stimuli, again leading to the impaired perception of other concurrent stimuli.

As in the ABC framework, competition is a core feature of these models. These models, however, consider only one type of competition: that between arousing and neutral stimuli/tasks. Critically, our empirical results indicate that arousal also influences competition between two neutral stimuli, such that processing of high-priority stimuli is enhanced, whereas processing of lower-priority stimuli is impaired. It is not clear how, in competition models that focus on competition between arousing and neutral stimuli, arousal would interact differently with low- and high-priority neutral information. For example, such models cannot account for the differential effects of arousing sounds on subsequent perceptually salient versus nonsalient letters (Fig. 1).

3.5. Competition between items for memory consolidation

In a different type of competition account, Diamond et al. (Reference Diamond, Park, Campbell and Woodson2005) propose that there is “ruthless competition” between novel and existing memory representations, such that encoding a new emotional experience suppresses recently potentiated synapses, creating memory for emotional events at the cost of memory for information learned just before the emotional event (Diamond et al. Reference Diamond, Park, Campbell and Woodson2005).

This ruthless competition hypothesis argues that the acquisition of new information via the hippocampus depotentiates the most recently activated synapses and that this suppression of recently formed memories is greater when the new information induces emotion or stress. Thus, inducing arousal should impair memory for a preceding sequence of items, regardless of whether those preceding items were themselves emotional or not. That is not the case, however. Inducing arousal via emotional or cold-pressor stress immediately after participants study a mixed list of emotional and neutral pictures selectively enhances memory for preceding emotional, but not neutral, pictures (Cahill et al. Reference Cahill, Gorski and Le2003; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Graham and Zorawski2008).

3.6. An arousing stimulus sometimes impairs and sometimes enhances memory of what just happened

How can inducing arousal enhance memory for preceding emotional items but not neutral items? Investigators proposed that emotional arousal “tags” synapses associated with representations of emotional items, making these synapses the selective target of protein synthesis-dependent long-term potentiation (Bergado et al. Reference Bergado, Lucas and Richter-Levin2011; Richter-Levin & Akirav Reference Richter-Levin and Akirav2003; Segal & Cahill Reference Segal and Cahill2009; Tully & Bolshakov Reference Tully and Bolshakov2010). The emotional tagging hypothesis predicts that emotionally salient stimuli are remembered better than neutral stimuli because emotional tags allow those particular synapses to capture the plasticity-related proteins released with subsequent inductions of arousal.

A problem for the emotional tagging model is that inducing emotional arousal sometimes enhances memory for preceding neutral stimuli (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Wais and Gabrieli2006; Dunsmoor et al. Reference Dunsmoor, Murty, Davachi and Phelps2015; Knight & Mather Reference Knight and Mather2009; Nielson & Powless Reference Nielson and Powless2007; Sakaki et al. Reference Sakaki, Fryer and Mather2014a). Neither the emotional tagging hypothesis nor any of the other hypotheses outlined earlier can account for this retrograde enhancement of something neutral. In contrast to the emotional tagging hypothesis, behavioral studies demonstrate that whether something arousing will yield retrograde enhancement or impairment depends on the priority of the preceding information (sect. 2.5) (Ponzio & Mather Reference Ponzio and Mather2014; Sakaki et al. Reference Sakaki, Fryer and Mather2014a).

3.7. Summary

Although there are many models describing how emotion enhances perception, attention, and memory in the brain, these theories fail to account for both the enhancing and impairing effects of emotional arousal (see Table 1 for a summary). In the following sections, we make the case for GANE, a model of how NE released under arousal can impact high- and low-priority representations differently despite its diffuse release across the brain.

4. Locus coeruleus, NE, and arousal

Like the GANE model, other theories also argue that the LC–NE system is important for emotion–cognition interactions (Markovic et al. Reference Markovic, Anderson and Todd2014; McGaugh Reference McGaugh2000; Reference McGaugh2004; McIntyre et al. Reference McIntyre, McGaugh and Williams2012). However, they have focused mostly on how NE interacts with the amygdala to enhance processing and consolidation of emotional stimuli at the expense of processing neutral stimuli (e.g., Strange & Dolan Reference Strange and Dolan2004; Strange et al. Reference Strange, Hurlemann and Dolan2003). In contrast, we argue that the LC–NE system promotes selectivity for any prioritized stimuli, irrespective of whether they are emotional or nonemotional.

In this section, we review the functional anatomy of the LC–NE system. A small nucleus in the brainstem known as the locus coeruleus (LC) releases NE when people are aroused – whether by a reward or punishment, a loud noise, or a disturbing image. LC axons are distributed throughout most of the brain (Gaspar et al. Reference Gaspar, Berger, Febvret, Vigny and Henry1989; Javoy-Agid et al. Reference Javoy-Agid, Scatton, Ruberg, L'heureux, Cervera, Raisman, Maloteaux, Beck and Agid1989; Levitt et al. Reference Levitt, Rakic and Goldman-Rakic1984; Swanson & Hartman Reference Swanson and Hartman1975), enabling NE to modify neural processing both locally and more globally in large-scale functional brain networks. How does the LC influence information processing in most cortical and subcortical regions? One might think that a hormone released under conditions of arousal would amp up brain activity. But instead, NE quiets most neuronal activity. In turn, this quiet backdrop makes those select few representations that NE amplifies stand out even more.

4.1. Functional neuroanatomy of the LC–NE system

The LC is the primary source of cortical NE and helps determine arousal levels (Berridge & Waterhouse Reference Berridge and Waterhouse2003; Berridge et al. Reference Berridge, Schmeichel and Espana2012; Samuels & Szabadi Reference Samuels and Szabadi2008a; Reference Samuels and Szabadi2008b). Tonic, or background, levels of LC activity help regulate levels of wakefulness (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Yizhar, Chikahisa, Nguyen, Adamantidis, Nishino, Deisseroth and de Lecea2010). Phasic, or transient, bursts of LC activity occur in response to novel, stressful, or salient stimuli (Aston-Jones & Bloom Reference Aston-Jones and Bloom1981; Foote et al.Reference Foote, Aston-Jones and Bloom1980; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Aston-Jones and Redmond1988; Sara & Bouret Reference Sara and Bouret2012; Sara & Segal Reference Sara and Segal1991; Vankov et al. Reference Vankov, Hervé-Minvielle and Sara1995) or to top-down signals associated with decision outcomes or goal relevance (Aston-Jones & Cohen Reference Aston-Jones and Cohen2005; Aston-Jones et al. Reference Aston-Jones, Rajkowski and Cohen1999). Emotionally salient stimuli also induce LC phasic activity irrespective of whether stimuli are positive (Bouret & Richmond Reference Bouret and Richmond2015; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Aston-Jones and Redmond1988) or aversive (Chen & Sara Reference Chen and Sara2007; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Aston-Jones and Redmond1988).

With highly divergent branching axons, the LC projects to every major region of cortex, despite its relatively small number of neurons (13,000 per hemisphere in humans) (Foote & Morrison Reference Foote and Morrison1987). Subcortical regions that underlie memory, attention, and emotional processing, including the hippocampus, frontoparietal cortex, and amygdala, are also innervated by the LC (Berridge & Waterhouse Reference Berridge and Waterhouse2003). LC axon varicosities release NE into extracellular space, allowing it to activate a broad swath of receptors within a diffusion zone (Beaudet & Descarries Reference Beaudet and Descarries1978; Descarries et al. Reference Descarries, Watkins and Lapierre1977; O'Donnell et al. Reference O'Donnell, Zeppenfeld, McConnell, Pena and Nedergaard2012).

In target brain sites, NE binds to multiple receptor subtypes (i.e., α1, α2, and β receptors) that are located both pre- and postsynaptically on neurons and astrocytes (Berridge & Waterhouse Reference Berridge and Waterhouse2003; O'Donnell et al. Reference O'Donnell, Zeppenfeld, McConnell, Pena and Nedergaard2012; Terakado Reference Terakado2014; Tully & Bolshakov Reference Tully and Bolshakov2010). Whereas α2-adrenoreceptors limit global and local NE release by acting as autoreceptors and decrease cell excitability, β-adrenoreceptor activation generally increases cell excitability, network activity, and synaptic plasticity (Berridge & Waterhouse Reference Berridge and Waterhouse2003; Marzo et al. Reference Marzo, Bai and Otani2009; Nomura et al. Reference Nomura, Bouhadana, Morel, Faure, Cauli, Lambolez and Hepp2014; Starke Reference Starke2001). α1-Adrenoreceptors recruit phospholipase activation and typically increase cell excitability via the inhibition of potassium channels (Wang & McCormick Reference Wang and McCormick1993). Thus, the relative density and localization of adrenoreceptor subtypes help determine how arousal-induced NE release will affect neural processing in different brain regions.

4.2. NE decreases neuronal noise in sensory regions during arousal

In the 1970s, researchers proposed that LC–NE activity enhances signal-to-noise ratios in target neurons in sensory regions (Foote et al. Reference Foote, Freedman and Oliver1975; Freedman et al. Reference Freedman, Hoffer, Woodward and Puro1977; Segal & Bloom Reference Segal and Bloom1976; Waterhouse & Woodward Reference Waterhouse and Woodward1980). For example, recording from individual neurons in awake squirrel monkeys revealed that NE application reduced spontaneous activity more than it reduced activity evoked by species-specific vocalizations (Foote et al. Reference Foote, Freedman and Oliver1975). Noradrenergic regulation of signal-to-noise ratios is characterized by two simultaneous effects: (1) most neurons in a population decrease spontaneous firing, and (2) the few neurons that typically respond strongly to the specific current sensory stimuli either show no decrease or an increase in firing, unlike the majority of neurons for which the stimuli typically evoke weak responses (Foote et al. Reference Foote, Freedman and Oliver1975; Freedman et al. Reference Freedman, Hoffer, Woodward and Puro1977; Hasselmo et al. Reference Hasselmo, Linster, Patil, Ma and Cekic1997; Kuo & Trussell Reference Kuo and Trussell2011; Livingstone & Hubel Reference Livingstone and Hubel1981; O'Donnell et al. Reference O'Donnell, Zeppenfeld, McConnell, Pena and Nedergaard2012; Oades Reference Oades1985; Waterhouse & Woodward Reference Waterhouse and Woodward1980).

Intracellular recording data in awake animals support and extend these early observations. Both inhibitory and excitatory neurons are depolarized in aroused cortex when mice run (Polack et al. Reference Polack, Friedman and Golshani2013). Yet, consistent with earlier reports of a quieter cortex under arousal, inhibitory neurons are more depolarized than excitatory neurons (Polack et al. Reference Polack, Friedman and Golshani2013). Moreover, surround inhibition dominates sensory responses during wakefulness compared with anesthesia, increasing the speed and selectivity of responses to stimuli in the center of the receptive field (Haider et al. Reference Haider, Häusser and Carandini2013). NE mediates the increase in widespread depolarization and the increase in inhibitory activity in visual cortex that together increase the signal-to-noise ratio (Polack et al. Reference Polack, Friedman and Golshani2013). The effect of NE has also been characterized as increasing the gain on the activation function of neural networks (Fig. 5) (Aston-Jones & Cohen Reference Aston-Jones and Cohen2005).

Figure 5. Norepinephrine gain modulation makes the non-linear input–output function more extreme, increasing the activity of units receiving excitatory input and decreasing the activity of units receiving inhibitory input. Adapted from Aston-Jones and Cohen (Reference Aston-Jones and Cohen2005).

Arousal is also characterized by cortical desynchronization, both globally when comparing wakefulness with anesthesia (Constantinople & Bruno Reference Constantinople and Bruno2011) or locomotion with being stationary (Polack et al. Reference Polack, Friedman and Golshani2013) and locally among neurons corresponding to attended representations (Fries et al. Reference Fries, Reynolds, Rorie and Desimone2001). Such decreases in cortical slow wave synchrony under arousal are likely mediated by LC activity (Berridge & Foote Reference Berridge and Foote1991; Berridge et al. Reference Berridge, Page, Valentino and Foote1993). Synchronous slow wave neural activity may gate sensory inputs, whereas desynchronized activity permits communication of cortical representations of stimuli across the brain (Luczak et al. Reference Luczak, Bartho and Harris2013). Cortical cell depolarization, desynchronization, and increased responsiveness to external input also occur with pupil dilation (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Froudarakis, Cadwell, Yatsenko, Denfield and Tolias2014; Vinck et al. Reference Vinck, Batista-Brito, Knoblich and Cardin2014), and pupil dilation tracks LC activity (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, O'Connell, O'Sullivan, Robertson and Balsters2014).

4.3 Summary

Years of research indicate that NE suppresses weak or random neuronal activity, but not strong activity. This is consistent with the increased selectivity seen under arousal (sect. 2). In the next section, we outline a model of how NE has such different outcomes depending on activity level.

5. Glutamate amplifies noradrenergic effects: The core noradrenergic selectivity mechanism under arousal

Now we turn to our GANE model, a novel brain-based account of how arousal amplifies priority effects in perception and memory. We propose that local glutamate–NE interactions increase gain under arousal. Glutamate is the most prevalent excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain (Meldrum Reference Meldrum2000). Glutamate receptors such as α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors mediate rapid excitatory synaptic transmission, neural network connectivity, and long-term memory (Bliss & Collingridge Reference Bliss and Collingridge1993; Lynch Reference Lynch2004; Traynelis et al. Reference Traynelis, Wollmuth, McBain, Menniti, Vance, Ogden, Hansen, Yuan, Myers and Dingledine2010).

In addition to point-to-point transmission across a synapse, some glutamate escapes the synaptic cleft, resulting in “glutamate spillover” (Okubo et al. Reference Okubo, Sekiya, Namiki, Sakamoto, Iinuma, Yamasaki, Watanabe, Hirose and Iino2010). In this section, we outline evidence that glutamate spillover attracts and amplifies local NE release via positive feedback loops. These self-regulating NE hotspots generate even greater excitatory activity in the vicinity of synapses transmitting high-priority representations, in contrast with NE's suppressive effects in the more widespread non–hotspot regions.

5.1. The NE hotspot: How local NE–glutamate positive feedback loops amplify processing of high-priority information

5.1.1 High glutamate activity stimulates adjacent NE varicosities to release more NE

The first demonstrations of glutamate-evoked effects on NE found that glutamate increased NE release via NMDA and non-NMDA glutamate receptors on LC axons (Fink et al. Reference Fink, Göthert, Molderings and Schlicker1989; Göthert & Fink Reference Göthert, Fink, Bönisch, Graefe, Langer and Schömig1991; Lalies et al. Reference Lalies, Middlemiss and Ransom1988; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Zaczek and Coyle1980; Pittaluga & Raiteri Reference Pittaluga and Raiteri1990; Reference Pittaluga and Raiteri1992; Vezzani et al. Reference Vezzani, Wu and Samanin1987; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Andrews and Thukral1992; see also Jones et al. Reference Jones, Snell and Johnson1987). In these studies, glutamate-evoked NE release occurred for NE varicosities in all cortical structures investigated in vitro: olfactory bulb, hippocampus, and throughout neocortex. In vivo experiments replicated the effect with targeted glutamate in rodent prefrontal cortex (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Valentino and Robine1992). Other neurotransmitters associated with arousal, such as histamine (Burban et al. Reference Burban, Faucard, Armand, Bayard, Vorobjev and Arrang2010) and orexin (Tose et al. Reference Tose, Kushikata, Yoshida, Kudo, Furukawa, Ueno and Hirota2009), enhance glutamate-evoked NE release. Central to our hypothesis, glutamate-evoked NE release occurs in human neocortex (Fink et al. Reference Fink, Schultheiß and Göthert1992; Luccini et al. Reference Luccini, Musante, Neri, Brambilla Bas, Severi, Raiteri and Pittaluga2007; Pittaluga et al. Reference Pittaluga, Pattarini, Andrioli, Viola, Munari and Raiteri1999).

How do these glutamate–NE interactions occur? LC axon varicosities rarely make direct synaptic contacts (e.g., only ~5% in rat cortex) (Vizi et al. Reference Vizi, Fekete, Karoly and Mike2010), but the distribution of these varicosities suggests they should often be found near glutamate terminals at excitatory synapses in neocortex (Benavides-Piccione et al. Reference Benavides-Piccione, Arellano and DeFelipe2005; Gaspar et al. Reference Gaspar, Berger, Febvret, Vigny and Henry1989). Another critical point is that LC neurons produce the NMDA receptor subunits needed for glutamate to modulate the release of NE from LC axon varicosities (Chandler et al. Reference Chandler, Gao and Waterhouse2014; Grilli et al. Reference Grilli, Zappettini, Zanardi, Lagomarsino, Pittaluga, Zoli and Marchi2009; Petralia et al. Reference Petralia, Yokotani and Wenthold1994; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Brodsky, Gorman and Inturrisi2003).

New technologies enable the visualization of glutamate spillover in cerebellum, neocortex, and hippocampus (Okubo et al. Reference Okubo, Sekiya, Namiki, Sakamoto, Iinuma, Yamasaki, Watanabe, Hirose and Iino2010; Okubo & Iino Reference Okubo and Iino2011). Multiple action potentials in a row yield sufficient spillover glutamate to activate nonsynaptic NMDA and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) (which are co-expressed on NE varicosities and enhance glutamate-evoked NE release in rodent and human cortices [Luccini et al. Reference Luccini, Musante, Neri, Brambilla Bas, Severi, Raiteri and Pittaluga2007]), but probably yield insufficient glutamate to recruit lower-affinity AMPA receptors (Okubo et al. Reference Okubo, Sekiya, Namiki, Sakamoto, Iinuma, Yamasaki, Watanabe, Hirose and Iino2010). Extracellular concentrations of the spillover rapidly decrease as distance from the synaptic cleft increases (Vizi et al. Reference Vizi, Fekete, Karoly and Mike2010), and the upper limit of glutamate spillover effects is estimated to be no greater than a few micrometers (Okubo & Iino Reference Okubo and Iino2011).

That spillover glutamate is sufficient to activate NMDA, but not AMPA receptors is another key factor. Unlike AMPA receptors, NMDA receptors require synchronized glutamate stimulation and neuron depolarization to activate (Lüscher & Malenka Reference Lüscher and Malenka2012). Thus, local glutamate spillover must co-occur with phasic depolarizing bursts of activity in LC neurons to recruit additional local NE release. Furthermore, a unique feature of NMDA receptors is that they require a co-agonist, which could be either glycine or D-serine (Wolosker Reference Wolosker2007). Glutamate stimulates astrocytes to release these co-agonists (Harsing & Matyus Reference Harsing and Matyus2013; Van Horn et al. Reference Van Horn, Sild and Ruthazer2013), and both glutamate and NE stimulate astrocytes to release glutamate (Parpura & Haydon Reference Parpura and Haydon2000). These additional glutamate interactions should further enhance NMDA receptor-mediated NE release (Fig. 6) (Paukert et al. Reference Paukert, Agarwal, Cha, Doze, Kang and Bergles2014). Together, these local glutamate–NE interactions support the emergence and sustainment of hotspots in the vicinity of the most activated synapses when arousal is induced.

Figure 6. Norepinephrine (NE) “hotspot” mechanism. (1A) Spillover glutamate (green dots) from highly active neurons interacts with nearby depolarized NE varicosities in a positive feedback loop involving N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and other glutamate receptors that leads to greater local NE release (maroon dots). The glutamatergic NMDA receptors require concomitant depolarization of noradrenergic axons (lightning symbol). Thus, hotspots amplify prioritized inputs most effectively under phasic arousal. (1B) Glutamate also recruits nearby astrocytes to release serine, glycine (orange dots), and additional glutamate. (2) Greater NE release creates concentration levels sufficient to activate low-affinity β-adrenoreceptors, which enhances neuron excitability. (3) Via activation of β- and α2A-auto-receptors, NE can stimulate and inhibit additional NE release, respectively. (4) Within hotspots, NE engages β-adrenoreceptors on pre-synaptic glutamate terminals to increase glutamate release. (5) Finally, NE binding to postsynaptic β-adrenoreceptors also inhibits the slow after-hyperpolarization, enabling the neuron to fire even longer. AMPA=α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; mGluR=metabotropic glutamate receptor.

Consistent with the existence of glutamate–NE interactions, local NE release in the region of an activated novel representation depends on the coincident timing of the novel event and an arousing event (Rangel & Leon Reference Rangel and Leon1995). For example, when footshock was administered to a rat while it explored a novel environment, NE levels rose substantially higher and remained elevated longer than when footshock was administered to the rat in its holding cage (Fig. 7) (McIntyre et al. Reference McIntyre, Hatfield and McGaugh2002). The amygdala presumably activated in response to the novelty of the new environment (Weierich et al. Reference Weierich, Wright, Negreira, Dickerson and Barrett2010), and glutamate associated with that representational network amplified the NE release initiated by the shock.

Figure 7. A rat receiving a foot shock (FS) in its home cage exhibits a brief increase in norepinephrine (NE) levels (gray triangles). A novel training environment does not increase NE on its own (black squares), but NE levels increase dramatically when shock is combined with that novel training environment (black diamonds). Figure reprinted with permission from McIntyre et al. (Reference McIntyre, Hatfield and McGaugh2002).

Hotspot effects have also been observed in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis immediately after training rats on an inhibitory avoidance task (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Chen and Liang2009). When infused separately at low doses, glutamate and NE each had no effect. But when infused together at the same low doses, they produced marked memory enhancements. Infusion of a higher dose of glutamate led to memory enhancements that were blocked by propranolol, indicating that the glutamate effect required β-adrenergic activity, which, as we describe next, is another key feature of our hotspot model.

5.1.2. α- and β-adrenoreceptors exert different effects on neuronal excitability and require different NE concentrations to be activated

To be engaged, β-adrenoreceptors require relatively high NE concentrations, α1-adrenoreceptors more moderate levels, and α2-adrenoreceptors the lowest NE concentrations (Ramos & Arnsten Reference Ramos and Arnsten2007). Thus, under arousal, α2-adrenoreceptor effects should be widespread, whereas β-adrenoreceptors should be activated only at hotspot regions because the local glutamate-evoked NE release there results in higher NE levels. Next, we describe the importance of this distinction for adrenergic autoreceptors.

5.1.3 Adrenergic autoreceptors inhibit or amplify their own NE release

Autoreceptors at NE varicosities serve as neural gain amplifiers by taking opposing action at low and high local levels of NE. The predominant presynaptic noradrenergic autoreceptor in humans is the α2A-adrenoreceptor (Starke Reference Starke2001), which inhibits NE release when it detects low or moderate levels of NE (Delaney et al. Reference Delaney, Crane and Sah2007; Gilsbach & Hein Reference Gilsbach, Hein, Südhof and Starke2008; Langer Reference Langer2008; Starke Reference Starke2001). In contrast, presynaptic β-adrenoreceptors amplify NE release when activated by high levels of NE (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Goshima and Misu1986; Misu & Kubo Reference Misu and Kubo1986; Murugaiah & O'Donnell Reference Murugaiah and O'Donnell1995a; Reference Murugaiah and O'Donnell1995b; Ueda et al. Reference Ueda, Goshima, Kubo and Misu1985). In addition, α2A-adrenoreceptors may lose affinity for NE when neurons are depolarized (Rinne et al. Reference Rinne, Birk and Bünemann2013), which would remove their inhibitory influence as a region becomes highly active. However, this loss of affinity recovers at saturating levels of NE (Rinne et al. Reference Rinne, Birk and Bünemann2013), which should help prevent the runaway excitation that could otherwise emerge because of the NE–glutamate feedback loop. Together with glutamate-evoked NE release (see sect. 5.1.1), the opposing effects of these different autoreceptors at low and high levels of NE provide an elegant way for the LC to modulate signal gain depending on the degree of local excitation.

5.1.4 Elevated local NE at hotspots engages β-adrenoreceptors on the glutamate terminals transmitting the prioritized representation

This stimulates an even greater release of glutamate, thereby amplifying the high-priority excitatory signal (Ferrero et al. Reference Ferrero, Alvarez, Ramirez-Franco, Godino, Bartolome-Martin, Aguado, Torres, Lujan, Ciruela and Sanchez-Prieto2013; Gereau & Conn Reference Gereau and Conn1994; Herrero & Sánchez-Prieto Reference Herrero and Sánchez-Prieto1996; Ji et al. Reference Ji, Cao, Zhang, Feng, Zhang, Ma and Li2008; Kobayashi et al. Reference Kobayashi, Kojima, Koyanagi, Adachi, Imamura and Koshikawa2009; Mobley & Greengard Reference Mobley and Greengard1985). That β-adrenoreceptors require relatively high NE concentrations to be engaged further biases this form of cortical autoregulation towards the most active synapses. Through these feedback processes, high-priority representations are “self-selected” to produce a stronger glutamate message and excite their connections more effectively under arousal. This stronger glutamate message should also promote selective memory of such stimuli (see sect. 6.1). In contrast, activation of lower threshold α2-adrenoreceptors inhibits glutamate release (Bickler & Hansen Reference Bickler and Hansen1996; Egli et al. Reference Egli, Kash, Choo, Savchenko, Matthews, Blakely and Winder2005), providing a mechanism for inhibiting lower-priority neural activity under arousal.

5.1.5 Higher NE levels at hotspots help prolong the period of neuronal excitation by temporarily inhibiting processes that normalize neuron activity

Under normal conditions, the slow after-hyperpolarization current habituates a postsynaptic neuron's responses following prolonged depolarization (Alger & Nicoll Reference Alger and Nicoll1980). However, even here, NE seems to benefit prioritized inputs by prolonging neuronal excitation via β-adrenoreceptors inhibiting the slow after-hyperpolarization (Madison & Nicoll Reference Madison and Nicoll1982; Nicoll Reference Nicoll1988).

In summary, different receptor subtypes enable NE to ignite hotspots in regions with high glutamate levels while inhibiting activity elsewhere. As we outline later, this diversity in NE receptor subtypes also plays an important role in shaping synaptic plasticity to favor prioritized representations under phasic arousal.

5.2. NE hotspots modulate interneurons and GABAergic transmission to increase lateral inhibition of competing representations

Increases in glutamate and NE at hotspots should also enhance inhibitory activity that mediates competition among neurons. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the most widespread inhibitory transmitter from neurons that suppress the responses of other neurons or neuronal circuits (Petroff Reference Petroff2002). Strong glutamate activity in cortical circuits stimulates local GABAergic activity, which increases the inhibitory effects of highly active regions on neighboring, competing neural circuits (Xue et al. Reference Xue, Atallah and Scanziani2014). Increases in NE also activate inhibition directly, with intermediate concentrations engaging maximal suppression (Nai et al. Reference Nai, Dong, Hayar, Linster and Ennis2009).

Subtypes of interneurons respond differently to NE in ways that should further increase neural gain. Although LC–NE activity activates interneurons that mediate lateral inhibition (Salgado et al. Reference Salgado, Garcia-Oscos, Martinolich, Hall, Restom, Tseng and Atzori2012a), it can also suppress interneurons with feedforward connections (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Walling, Milway and Harley2005), such that a strong signal will inhibit competing representations while enhancing activity in other neurons within its processing pathway.

5.3. NE directs metabolic resources to where they are most needed

To optimize processing of salient events, NE also helps coordinate the delivery of the brain's energy supplies, allowing it to mobilize resources quickly when needed (e.g., Toussay et al. Reference Toussay, Basu, Lacoste and Hamel2013). The brain's most essential energy supplies, oxygen and glucose, are delivered via the bloodstream. One key way that NE coordinates energy delivery is by increasing the spatial and temporal synchronization of blood delivery to oxygen demand within the brain. For example, in mice, as NE levels increase, overall blood vessel diameter in the brain decreases, but the spatial and temporal selectivity of blood distribution to active task-relevant regions increases (Bekar et al. Reference Bekar, Wei and Nedergaard2012).

In addition to distributing blood flow, NE also interacts with astrocytes locally to mobilize energy resources throughout the cortex. When a particular area of the brain needs more energy, it can obtain fuel not only from glucose, but also from glycogen in astrocytes (Pellerin & Magistretti Reference Pellerin and Magistretti2012). NE speeds up the process of obtaining energy from glycogen (Magistretti et al. Reference Magistretti, Morrison, Shoemaker, Sapin and Bloom1981; Sorg & Magistretti Reference Sorg and Magistretti1991; Walls et al. Reference Walls, Heimbürger, Bouman, Schousboe and Waagepetersen2009). While α1- and α2-adrenoreceptors mediate glutamate uptake and glycogen production in astrocytes, β-adrenoreceptors stimulate the breakdown of glycogen to provide rapid energy support in highly active local regions (O'Donnell et al. Reference O'Donnell, Zeppenfeld, McConnell, Pena and Nedergaard2012), further amplifying NE hotspot activity.

5.4. Summary

At the local neuronal level, NE suppresses most activity, but amplifies the strongest activity as a result of the differential effects of NE on different adrenoreceptor subtypes. The amplification of strong activity occurs via “NE hotspots,” where positive feedback loops between local NE and glutamate release increase the strength of activated representations. To sustain higher levels of activity, hotspots also recruit limited metabolic resources. At the circuit level, the increased glutamate and NE produced at hotspots recruit nearby astrocytes that supply additional energy to active neurons. On a broader scale, NE facilitates the redistribution of blood flow towards hotspots and away from areas of lower activity. Thus, by influencing multiple levels of brain function, NE selectively amplifies self-regulating processes that bias processing in favor of prioritized information.

6. Roles of the LC–NE system in memory

So far we have focused on how arousal increases the gain on prioritization processes in perception, attention, and initial memory encoding. Now we turn to memory consolidation processes. Experiencing an emotionally intense event influences the vividness and longevity of recent memory traces, enhancing or impairing them based on their priority (e.g., Fig. 4) (Knight & Mather Reference Knight and Mather2009; Sakaki et al. Reference Sakaki, Fryer and Mather2014a). Much research has indicated that NE is involved in memory consolidation effects (for a review, see McGaugh [Reference McGaugh2013]), but there has been little focus on the interplay between NE's enhancing and impairing effects during memory consolidation.

The durability of memories depends on adjustments in the strength of communication across synapses via processes known as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). Whether neural activity triggers LTP or LTD depends on the relative timing of spikes in pre- and postsynaptic neurons (Nabavi et al. Reference Nabavi, Fox, Proulx, Lin, Tsien and Malinow2014), and whether LTP and LTD are maintained depends on protein synthesis processes (Abraham & Williams Reference Abraham and Williams2008). We propose that two main NE mechanisms modulate LTP and LTD, leading to “winner-take-more” and “loser-take-less” outcomes in long-term memory: (1) hotspot modulation of the probability of LTP (higher NE levels engaging LTP) and LTD (relatively lower NE levels promoting LTD), and (2) NE-enhanced protein synthesis supporting long-term maintenance of LTP and LTD.

6.1. NE gates spike-timing-dependent LTD and LTP

Long-term potentiation and long-term depression are often studied in brain slices in a petri dish using high-frequency electric stimulation to induce LTP and repeated slow stimulation to induce LTD. But in the brain's natural context involving constant barrages of pre-synaptic activity generating postsynaptic spikes, the relative timing of pre- and postsynaptic activity helps determine whether LTP or LTD occurs. Furthermore, to avoid constant up-and-down adjustment of synapses based on random firing patterns, neuromodulators such as NE and dopamine signal when the relationship between pre-synaptic and postsynaptic activity is likely to be meaningful (Pawlak et al. Reference Pawlak, Wickens, Kirkwood and Kerr2010). In vivo studies indicate that spike-timing-dependent LTP or LTD requires these neuromodulators (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Rozas, Treviño, Contreras, Yang, Song, Yoshioka, Lee and Kirkwood2014; Johansen et al. Reference Johansen, Diaz-Mataix, Hamanaka, Ozawa, Ycu, Koivumaa, Kumar, Hou, Deisseroth and Boyden2014). In particular, by binding to G-coupled receptors, NE modulates kinases and phosphatases that determine whether LTP or LTD induction occurs (Treviño et al. Reference Treviño, Huang, He, Ardiles, De Pasquale, Guo, Palacios, Huganir and Kirkwood2012b; Tully & Bolshakov Reference Tully and Bolshakov2010).

Different adrenoreceptor subtypes appear to mediate NE's regulation of spike-timing-dependent LTP and LTD. Spike-timing-dependent LTP is initiated primarily by β-adrenoreceptor activation, whereas α1-adrenoreceptors promote spike-timing-dependent LTD (Salgado et al. Reference Salgado, Kohr and Trevino2012b). Critically, Salgado and colleagues reported that the LTP promoting activation of β-adrenoreceptors requires concentrations of NE ~25-fold higher (8.75 µM) than the NE concentration that promotes α1-adrenoreceptor-mediated spike-timing-dependent LTD (0.3 µM) in vitro. This agrees with an in vivo estimate of a 30-fold increase in NE associated with LTP in dentate gyrus (Harley et al. Reference Harley, Lalies and Nutt1996). The increase in NE required to support spike-timing-dependent LTP is substantially higher than the increases in NE levels seen when experimenters stimulate LC and measure NE in cortex or hippocampus using microdialysis (e.g., approximately twice baseline [Florin-Lechner et al. Reference Florin-Lechner, Druhan, Aston-Jones and Valentino1996], ~0.5 µM [Palamarchouk et al. Reference Palamarchouk, Zhang, Zhou, Swiergiel and Dunn2000]). Thus, there is a discrepancy between the NE levels needed for spike-timing-dependent LTP to occur and the levels measured in laboratory studies. Our GANE model accounts for this difference, as it posits that LC activation interacts with prioritized representations to elicit much higher NE release in a select few local hotspots than elsewhere, such that the average cortical sampling location would not detect the NE levels needed to support LTP.

The NE hotspot model supports a range of simultaneous NE modulatory actions. At high-priority hotspots, NE levels should be sufficiently high to engage β-adrenoreceptors and initiate spike-timing-dependent LTP (Salgado et al. Reference Salgado, Kohr and Trevino2012b; Treviño et al. Reference Treviño, Huang, He, Ardiles, De Pasquale, Guo, Palacios, Huganir and Kirkwood2012b). Conversely, areas with lower glutamate activity, where NE levels are by comparison modestly increased, would undergo LTD as a result of the engagement of relatively higher affinity α1-adrenergic receptors (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Rozas, Treviño, Contreras, Yang, Song, Yoshioka, Lee and Kirkwood2014; Salgado et al. Reference Salgado, Kohr and Trevino2012b; Treviño et al. Reference Treviño, Frey and Köhr2012a). Variations in NE levels in the alert brain thereby support bidirectional plasticity (Salgado et al. Reference Salgado, Kohr and Trevino2012b; Treviño et al. Reference Treviño, Huang, He, Ardiles, De Pasquale, Guo, Palacios, Huganir and Kirkwood2012b).

6.2. NE increases protein synthesis processes that promote memory consolidation: Critical role of β-adrenoreceptors

Arousal levels in the minutes and hours before or after an event also influence later memory for it. Here we review evidence that these wider time window effects of arousal depend on NE's enhancement of protein synthesis processes that determine the long-term durability of salient memories. Critically, such regulation of memory processes by NE appears to be mediated by β-adrenoreceptors, which we propose are selectively activated in high-priority representational networks.

The role of NE in gating the synthesis of plasticity-related proteins has been recognized for more than a decade (Cirelli et al. Reference Cirelli, Pompeiano and Tononi1996; Cirelli & Tononi Reference Cirelli and Tononi2000). For example, plasticity-related proteins promoted by an LC–NE novelty signal can enhance long-term memory consolidation of another salient, but otherwise poorly consolidated event (i.e., learning that stepping off of a platform leads to a weak shock) that occurs 1 hour later or even 1 hour prior to the novelty experience (Moncada & Viola Reference Moncada and Viola2007; Moncada et al. Reference Moncada, Ballarini, Martinez, Frey and Viola2011).

Blocking β-adrenoreceptors or protein synthesis prior to novelty exposure prevents novelty facilitation of LTP (Straube et al. Reference Straube, Korz, Balschun and Frey2003). What is particularly striking is that β-adrenoreceptor activation at time 1 primes synapses to induce LTP at time 2 an hour later, even when β-adrenoreceptors are blocked by propranolol during time 2 (Tenorio et al. Reference Tenorio, Connor, Guévremont, Abraham, Williams, O'Dell and Nguyen2010). However, if protein synthesis processes are blocked during time 2, the time 1 priming event does not lead to enhancement. The plasticity marker, Arc protein, is recruited by β-adrenoreceptor activation in the presence of NMDA receptor activation (Bloomer et al. Reference Bloomer, VanDongen and VanDongen2008). Hotspots are characterized by high levels of glutamate release and β-adrenoreceptor activation; thus, emotional arousal should elevate Arc selectively in NE hotspots.

β-Adrenergic activation after learning or weak LTP induction can also convert short-term LTP to more lasting protein synthesis-dependent late LTP (Gelinas & Nguyen Reference Gelinas and Nguyen2005; Gelinas et al. Reference Gelinas, Tenorio, Lemon, Abel and Nguyen2008). Likewise, stimulating the basolateral amygdala either before or after tetanization of the hippocampus converts early LTP to late LTP via a β-adrenoreceptor mechanism (Frey et al. Reference Frey, Bergado-Rosado, Seidenbecher, Pape and Frey2001). Activation of β-adrenoreceptors also shields late LTP from subsequent depotentiation (Gelinas & Nguyen Reference Gelinas and Nguyen2005; Katsuki et al. Reference Katsuki, Izumi and Zorumski1997).

Creation of long-lasting memories depends on the protein synthesis cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA)/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) pro-signaling cascade (Kandel Reference Kandel2012; O'Dell et al. Reference O'Dell, Connor, Gelinas and Nguyen2010). Neuronal ensembles in which the cAMP/PKA/CREB cascade has been activated, as happens with the engagement of β-adrenoreceptors, have been found to be selectively allocated to the engram representing a memory (Han et al. Reference Han, Kushner, Yiu, Cole, Matynia, Brown, Neve, Guzowski, Silva and Josselyn2007). Furthermore, increasing excitability via different methods mimics the effects of CREB overexpression, suggesting that neurons are recruited to an engram based on their neural excitability (Frankland & Josselyn Reference Frankland and Josselyn2015; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Won, Karlsson, Zhou, Rogerson, Balaji, Neve, Poirazi and Silva2009). Thus, by modulating CREB and other aspects of neural excitability, NE hotspots should help determine which neurons are allocated to an engram and stabilized in long-term memory.

6.3. Summary

Local NE concentration is the key to understanding how NE mediates arousal's dichotomous effects on memory. Previous research has indicated that different NE levels regulate different forms of spike-timing-dependent plasticity by engaging distinct adrenoreceptors. Whereas NE binding to moderate-affinity α1-adrenergic receptors leads to LTD and memory suppression, NE binding to lower-affinity β-adrenoreceptors leads to LTP and memory enhancement. We propose that local discrepancies in NE levels arise from self-regulating NE–glutamate interactions. Where NE concentrations become high enough to engage low-affinity β-adrenoreceptors, a cascade of intracellular events triggers protein synthesis processes that enable long-term memory consolidation of the high-priority trace. In contrast, more modest increases in NE levels at less active regions lead to LTD, ensuring less important events are forgotten. Before or after encoding, the confluence of protein synthesis and β-adrenoreceptor activation selectively strengthens memory consolidation when these mechanisms are recruited close in time.

7. Beyond local GANE: Broader noradrenergic circuitry involved in increased selectivity under arousal

Beyond local effects, NE increases biased competition processes by altering how different brain structures interact. With its widely distributed afferents, the LC–NE system influences neural processing in many brain regions when an arousing event occurs. NE release can translate local hotspot effects to more global winner-take-more effects by modulating neuronal oscillations. Furthermore, cortical and subcortical priority signals modulate glutamate release in sensory regions and the hippocampus as mental representations are formed and sustained. As previously reviewed (see sect. 5.1), glutamate is essential for NE release to selectively amplify the processing of significant information. Thus, by stimulating local glutamate release and recruiting LC firing, key brain structures can optimize synaptic conditions for arousal to ignite hotspots.

7.1. Activation of inhibitory networks by NE primes neuronal synchronization among high-priority neural ensembles

So far, we have reviewed evidence that NE hotspots amplify the effects of priority, enhancing salient features while suppressing noisy background activity. In this section, we discuss the possibility that neuronal oscillations communicate activity in local hotspots more globally (Singer Reference Singer1993).

The first candidate is gamma synchrony (30–80 Hz). Conceptual frameworks of neural oscillations posit that gamma synchrony supports gain modulation in local networks (Fries Reference Fries2009), such that a target area can oscillate in phase with only one of two competing inputs. As a result, the synaptic input that more successfully synchronizes its activity with the target region is amplified, whereas the less synchronized input is suppressed. Gamma synchrony is likely a key component of selective attention (Baluch & Itti Reference Baluch and Itti2011; Fries Reference Fries2009; Fries et al. Reference Fries, Reynolds, Rorie and Desimone2001).

Gamma oscillations are generated by a feedback loop between excitatory pyramidal cells and fast-spiking parvalbumin-positive inhibitory interneurons (Buzsáki & Wang Reference Buzsáki and Wang2012; Cardin et al. Reference Cardin, Carlen, Meletis, Knoblich, Zhang, Deisseroth, Tsai and Moore2009; Carlen et al. Reference Carlen, Meletis, Siegle, Cardin, Futai, Vierling-Claassen, Ruhlmann, Jones, Deisseroth, Sheng, Moore and Tsai2012; Sohal et al. Reference Sohal, Zhang, Yizhar and Deisseroth2009). Noradrenergic release activates these interneurons (Cox et al. Reference Cox, Racca and Lebeau2008; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Huganir and Kirkwood2013; Toussay et al. Reference Toussay, Basu, Lacoste and Hamel2013) and increases gamma synchrony in these target regions (Gire & Schoppa Reference Gire and Schoppa2008; Haggerty et al. Reference Haggerty, Glykos, Adams and LeBeau2013; Marzo et al. Reference Marzo, Totah, Neves, Logothetis and Eschenko2014). Emotional arousal also modulates gamma oscillations in regions that process motivational significance, such as the amygdala, sensory cortex, and prefrontal cortex (Headley & Weinberger Reference Headley and Weinberger2013). These results suggest that arousal-induced NE release selectively biases gamma oscillations in favor of the most activated representations in local neuronal ensembles.

Consistent with the hotspot model, increases in local gamma power during cognitive processing in humans are associated with increases in glutamate levels (Lally et al. Reference Lally, Mullins, Roberts, Price, Gruber and Haenschel2014). Increases in local gamma power are also associated with successful memory encoding in humans (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Zaghloul, Jacobs, Williams, Sperling, Sharan and Kahana2013). Likewise, in rats, fear conditioning increases gamma synchronization in sensory cortex (Headley & Pare Reference Headley and Pare2013). Increased gamma power predicts retention of tone–shock associations and enhanced representations of the tone associated with shock in the primary auditory cortex (Headley & Weinberger Reference Headley and Weinberger2011).

Recent research indicates that β-adrenoreceptors recruit in-phase oscillations with gamma activity, whereas α1-adrenoreceptors recruit out-of-phase oscillations (Haggerty et al. Reference Haggerty, Glykos, Adams and LeBeau2013). Given the higher threshold for activating β-adrenergic than α1-adrenergic receptors (see sect. 5.1), these results suggest that high NE levels at hotspots engage β-adrenoreceptors, recruit in-phase oscillations, and increase local network connectivity for prioritized representations. Elsewhere, lower NE levels should only be sufficient to engage α1-adrenoreceptors and thereby reduce local gamma power and diminish local synchronization.