Introduction

But Scheherazade rejoiced with exceeding joy and got ready all she required and said to her younger sister, Dunyazad, “Note well what directions I entrust to thee! When I have gone in to the King I will send for thee and when thou comest to me and seest that he hath had his carnal will of me, do thou say to me: O my sister, [if] thou be not sleepy, relate to me some new story, delectable and delightsome, the better to speed our waking hours; and I will tell thee a tale which shall be our deliverance, if so Allah please, and which shall turn the King from his blood-thirsty custom.”Footnote 1

Presented in the well-known collection of folktales One Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade's “delectable and delightsome” stories weave together rich narratives of fantasy and allure, encompassed within an over-arching framework of survival and redemption.Footnote 2 The main narrative evokes a Middle Eastern setting, introducing the Sultan Shahryar, ruler of the Sasanian Empire.Footnote 3 Upon learning of his wife's infidelity, the Sultan orders her execution. He then vows to protect himself from any future betrayal by marrying only virgins, consummating the marriages, and killing the women the next morning. After the Sultan establishes this pattern, Scheherazade seeks to become his wife with a plan to overcome his cruelty.Footnote 4 On their wedding night, Scheherazade begins to tell him a tale and leaves it unresolved. She continues telling stories of magic, romance, and adventure little by little each night to keep the Sultan curious and thereby postpone her execution. Through the course of her storytelling, the Sultan undergoes a transformation from brutal to merciful and grants Scheherazade her life.

While composers such as Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Maurice Ravel have responded to this source material by musically evoking the narrative and its sound-world, few compositions engaging with this material directly interrogate issues of gender and ethnic identity. Scheherazade.2, however, does address these issues by uniquely problematizing the implications of programmatic musical representation and the contingency of hermeneutical interpretation.Footnote 5 Composed in 2014 by John Adams (b. 1947), Scheherazade.2 brings the story-world of One Thousand and One Nights into the twenty-first century. Rather than conveying the fantastical tales told by Scheherazade, Adams introduces a modern representation of the protagonist and her personal story. Claiming to address misogyny through his musical storytelling, Adams describes the violence that permeates One Thousand and One Nights and refers to similar examples reflected in contemporary news and media images:

Thinking about what a Scheherazade in our own time might be brought to mind some famous examples of women under threat for their lives, for example the “woman in the blue bra” in Tahrir Square, dragged through the streets, severely beaten, humiliated and physically exposed by enraged, violent men. Or the young Iranian student, Neda Agha-Soltan, who was shot to death while attending a peaceful protest in Teheran [sic]. Or women routinely attacked and even executed by religious fanatics in any number of countries—India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, wherever. The modern images that come to mind certainly aren't exclusive to the Middle East—we see examples, if not quite so graphic nonetheless profoundly disturbing, from everywhere in the world including in our own country [United States] and even on our own college campuses.Footnote 6

John Adams explains that Scheherazade.2 was motivated by an exhibit featuring the history and evolution of One Thousand and One Nights at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris in 2012. Struck by the underlying violence and brutality in the folktales, he imagined a modern Scheherazade facing misogyny in the world today. Adams's suggested narrative of a twenty-first-century Scheherazade is conveyed in his symphony's four movements: I. Tale of the Wise Young Woman—Pursuit by True Believers; II. A Long Desire (Love Scene); III. Scheherazade and the Men with Beards; IV. Escape, Flight, Sanctuary. Adams provides an extra-musical program to guide interpretations, offering an outline of the story but allowing the individual listener to fill in the details:

So I was suddenly struck by the idea of a “dramatic symphony” in which the principal character role is taken by the solo violin—and she would be Scheherazade. While not having an actual story line or plot, the symphony follows a set of provocative images: a beautiful young woman with grit and personal power; a pursuit by “true believers”; a love scene which is both violent and tender; a scene in which she is tried by a court of religious zealots (“Scheherazade and the Men with Beards”), during which the men argue doctrine among themselves and rage and shout at her only to have her calmly respond to their accusations; and a final “escape, flight and sanctuary,” which must be the archetypal dream of any woman importuned by a man or men.Footnote 7

These notes appear on John Adams's webpage for Scheherazade.2, in the liner notes of the 2016 Nonesuch album, and in many programs distributed at live performances, exposing listeners to Adams's conceptions of his composition. By engaging with the program provided by the composer, a listener can approach the music with a particular frame of mind to imagine the dramatic action and settings that may correspond to salient musical events. However, the ambiguity in program music allows for interpretive flexibility as other ideas interact with the listener's experience of the music.Footnote 8 Even a slight alteration to the program notes can drastically impact the interpreted story. The notes accompanying some concert hall performances have in fact included a slightly different version of the story: the phrase describing the second movement's love scene, “which is both violent and tender,” is replaced by the provocative suggestion, “(who knows… perhaps her lover is also a woman?).”Footnote 9 While the audience is free to accept or reject the program in part or in whole, the suggestions Adams provides and their shifting details carry significant implications for interpretation.Footnote 10 Nevertheless, the program is only one component within the network of variables shaping the paradigm of subjectivity that determines how listeners might respond to the musical story.

The meaning a particular listener will derive from Scheherazade.2 is contingent upon a multiplicity of factors, highlighting power dynamics that involve complex interactions of agency, identity, and influence of interpretation.Footnote 11 The interactions of these components are further complicated as they intersect with Middle Eastern feminist concerns regarding Western representation of subjectivity. While a work such as Scheherazade.2 might typically invite either a feminist critique or an orientalist critique, this article blends the two lenses, using the framework of feminist orientalism to examine the intertwined implications of both angles of critique.Footnote 12 As a Western project alluding to the Arabian world of Scheherazade and the Sultan to tell a story about misogyny, Scheherazade.2 effectively construes such issues of misogyny as “Eastern.” The effect of displacing these problems of violence and oppression onto the East arguably provides a more palatable way for Western audiences to critique the West itself but ultimately impedes transnational efforts. While seeking broad-scale reparation and advocacy, Scheherazade.2 nevertheless reinscribes orientalist stereotypes through the constructed narrative of a gendered and racial “Other.” Through the course of this article, I apply a feminist orientalist critique—to the programmatic and musical representations; to the agency of listener, composer, and performer; and to the influence of different experiential contexts—to evaluate the ways in which Scheherazade.2 works to challenge and redress issues of misogyny while also perpetuating discourses of essentialization and appropriation. I argue overall that, by recognizing the feminist orientalist implications of Scheherazade.2, the reparative potential of the piece can be foregrounded and genuinely realized in a transnational context.Footnote 13

Feminist Orientalism and Middle Eastern Feminism

Scheherazade.2 tangles with representations of gender and ethnicity, extending beyond the proposed musical narrative to deeper dynamics of identity and power relations. By presenting a program describing Scheherazade's struggles and empowerment, Scheherazade.2 engages with contemporary socio-political issues of gender and ethnicity, implicated musically through tropes of femininity and exoticism. Scholars have discussed these tropes in terms of music and music scholarship reflecting gendered and imperial discourse, resonating with broader projects of feminism and decolonization studies that address issues of essentialism and appropriation.Footnote 14

Feminist scholars have, in recent years, engaged Edward Said's Orientalism Footnote 15 to examine the position of gender within the construction of this cultural dichotomy; as an imperialist masculine discourse, orientalism effectively feminizes the East as the “Other” of the dominant male Western figure.Footnote 16 As Lila Abu-Lughod describes, Said's work opened space in feminist scholarship and Middle East studies for new discussions: examining the gender and sexuality of orientalist discourse; deconstructing gender relations and stereotypes of the Middle Eastern woman; illuminating Middle Eastern feminism; and evaluating feminist critique within a global context.Footnote 17 Such lines of inquiry have contributed to considerations of how Western feminism is complicit in both challenging and perpetuating essentializing stereotypes. By imposing Western values and conceptions on generalized discussions of agency and subjecthood, Western feminist projects often reinscribe the orientalizing power binary.Footnote 18 As Abu-Lughod warns:

First, we have to ask what Western liberal values we may be unreflectively validating in proving that “Eastern” women have agency, too… The problem is about the production of knowledge in and for the West… As long as we are writing for the West about “the other,” we are implicated in projects that establish Western authority and cultural difference.Footnote 19

Abu-Lughod's concerns provide a foundation for approaching Scheherazade.2: as a Western musical project about the “Other,” how might this composition be complicit in reinscribing Western authority and cultural difference?

Sertaç Sehlikoglu describes waves of feminist scholarship and recent trends in the discussion of agency and subjecthood, illustrating how these themes have been conceived and reconceived in recognition of bias and in response to cultural and historical contexts.Footnote 20 Sehlikoglu identifies a key concern extending across these waves in terms of agency and power. Due to a Western bias towards “interpreting difference and asymmetry as inequality and hierarchy,” important sites of Middle Eastern women's agency are erased: “The troublesome portrayal of Muslim women ‘as victims of male brutality who must be rescued from traditional, oppressive male morality, which is imagined as a total control over female bodies and actions’ has proven to be the dominant obstacle in Middle Eastern scholarship.”Footnote 21 By framing power and agency in such ways, scholarly attempts to elevate women effectively disempower them through orientalizing implications. The focus on the representation of agency and subjectivity will further guide the critique of Scheherazade.2 throughout this article.

The issues posed by Abu-Lughod and Sehlikoglu demonstrate the need to recognize and address bias in Western feminist projects. In scholarship as well as in other cultural mediums, the Western producer's conscious or unconscious assertion of Western values over those of the “Other” fails to fully recognize agency and reinscribes the power binary favoring the West. This reinscription of orientalizing tropes manifests significantly in the framework of feminist orientalism. In her description of this concept, Joyce Zonana draws from Saad Abdulrahman Al-Bazei's idea of Western “self-redemption”: “transforming the Orient and Oriental Muslims into a vehicle for… criticism of the West itself.”Footnote 22 Zonana adapts this idea to feminist critique, exploring the implication of gender dynamics in orientalizing rhetoric. By projecting the issues of oppression onto an Eastern subject and thereby displacing the source of misogyny, the reinscription of the “Other” enables Western consumers to contemplate local problems without threatening their “Western superiority.” Feminist orientalist critique highlights this problematic reinforcement of Western superiority; by recognizing these implications, scholars can address and counteract how the proliferation of stereotypes and assumptions about the East are being used to further the Western feminist project. Instead, efforts can be made to pave the way to “establishing genuine alliances among women of different cultures” and engage “more self-critical, balanced analysis of the multiple forms both of patriarchy and of women's power.”Footnote 23 A critique of Scheherazade.2 informed by the framework of feminist orientalism enables a deep exploration parsing the paradoxical nuances of the music and its broader implications.

Distinct cultural perspectives and attitudes contribute to particular articulations of the power dynamics between “the West” and “the East.” The concept of American orientalism provides a lens for applying feminist orientalist critique to the unique implications of the “imperial feelings” infused in the U.S. cultural position. Sunaina Maira describes American orientalism as a form of orientalism distinct from the history of European colonization; instead, it is driven by America's “imperialism without colonies,” the nationalistic conquest and appropriation of “Other” cultures.Footnote 24 Drawing from William Appleman Williams, Maira explains the “imperial feelings” that underlie the American “empire as a way of life”: “Imperial feelings are the complex of psychological and political belonging to an empire that are often unspoken, sometimes subconscious, but always present, the ‘habits of heart and mind’ that infuse and accompany structures of difference and domination… U.S. imperial culture also displays feelings of imperial guilt… ambivalence about empire.”Footnote 25 These “imperial feelings” manifest, for example, in the case of “white savior complex,” the perceived motivation of a Western subject's mission to rescue the “Othered” woman from her oppressive Third World culture.Footnote 26 American orientalism and its “imperial feelings” contribute to feminist orientalist discourse through continued explicit or implicit “Othering.” These intersecting theories provide a space for parsing the multiplicity of stories comprising Scheherazade.2 and the ways in which this composition challenges and reinforces orientalizing stereotypes and oppression.

Framing the Musical Narrative

As listeners approach Scheherazade.2, their perceptions of the musical story will be shaped not only by Adams's programmatic descriptions and commentary, but also by various other factors surrounding the themes and performances of the piece. For example, listeners recognizing the issues of misogyny presented in the program may experience the music in the contexts of both the Me Too movement—whether in its original 2006 context or in the context of its viral social media proliferation in 2017—and the Washington, D.C. Women's March of January 2017. More literary-minded listeners may focus on their past exposure to One Thousand and One Nights, imagining the fantastical folk tales as they experience the dramatic symphony. The medium through which a listener encounters the music also affects its interpretation, whether first heard in a live performance or through the one existing recording released by Nonesuch in 2016 with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. Scheherazade.2 has been performed by dozens of symphony orchestras in the United States and internationally since its premiere in 2015, with each performance presenting the piece in a slightly different context of programming.Footnote 27

As a significant example of programming, Adams's piece may be paired with Scheherazade, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's well-known nineteenth-century representation of One Thousand and One Nights. Footnote 28 If audience members were to attend a concert of Scheherazade followed by Scheherazade.2, they would experience the juxtaposition of the Romantic story and the modern story, with the added “point 2” suggesting that Adams's piece might be considered as a sequel to Rimsky-Korsakov's. A brief exploration of Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade demonstrates the narrative approach that audiences may adopt to inform readings of Adams's piece.

Composed in 1888, Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade portrays various scenes from One Thousand and One Nights. The four-movement symphonic suite imitates the overarching frame structure of the folktales as individual stories conveyed in each movement.Footnote 29 Various musical themes depicting characters and events interact throughout the piece, with the prominent solo violin representing Scheherazade's narrative voice.Footnote 30 Through Scheherazade, Rimsky-Korsakov evokes romantic, fantastical stories just as Scheherazade related, such that listeners “carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an Oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairy-tale wonders.”Footnote 31 As a modern foil to Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, Scheherazade.2 engages the same diegesis but differs in that it focuses on the narrating protagonist rather than the stories she tells. Adams also employs a four-movement form for his dramatic symphony, and he also constructs Scheherazade's voice through a solo violin part.Footnote 32 While musical events in the two works play out differently, the intertextuality of symphonic structure, violin narrative role, and shared literary source material can shape perceptions of characters and events. Imbued with sexual politics and exotic musical tropes, the accrued meaning of Scheherazade sets a precedent for the interpretive mindset carried into Scheherazade.2.

Rimsky-Korsakov's suite begins with a loud, low unison statement in E minor, with a heavy expressive marking and in the dark timbres of low brass, clarinet, bassoon, violin, and low strings. The foreboding nature of the strong dynamics and accented rhythm suggest that this theme represents the Sultan (Example 1).Footnote 34

Example 1. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, first movement, the Sultan's theme, mm. 1–7.Footnote 33

The solo violin theme follows as a musical opposition to the Sultan (Example 2).Footnote 35 The smooth and virtuosic undulating line and the high register singing quality of the violin's timbre suggest stereotyped conceptions of femininity, indicating the persona of Scheherazade. Her expressive cadenza segues into the musical storytelling, in which instruments and themes may be associated with the characters and events suggested in the programmatic movements.

Example 2. Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, first movement, Scheherazade's theme, mm. 14–17.

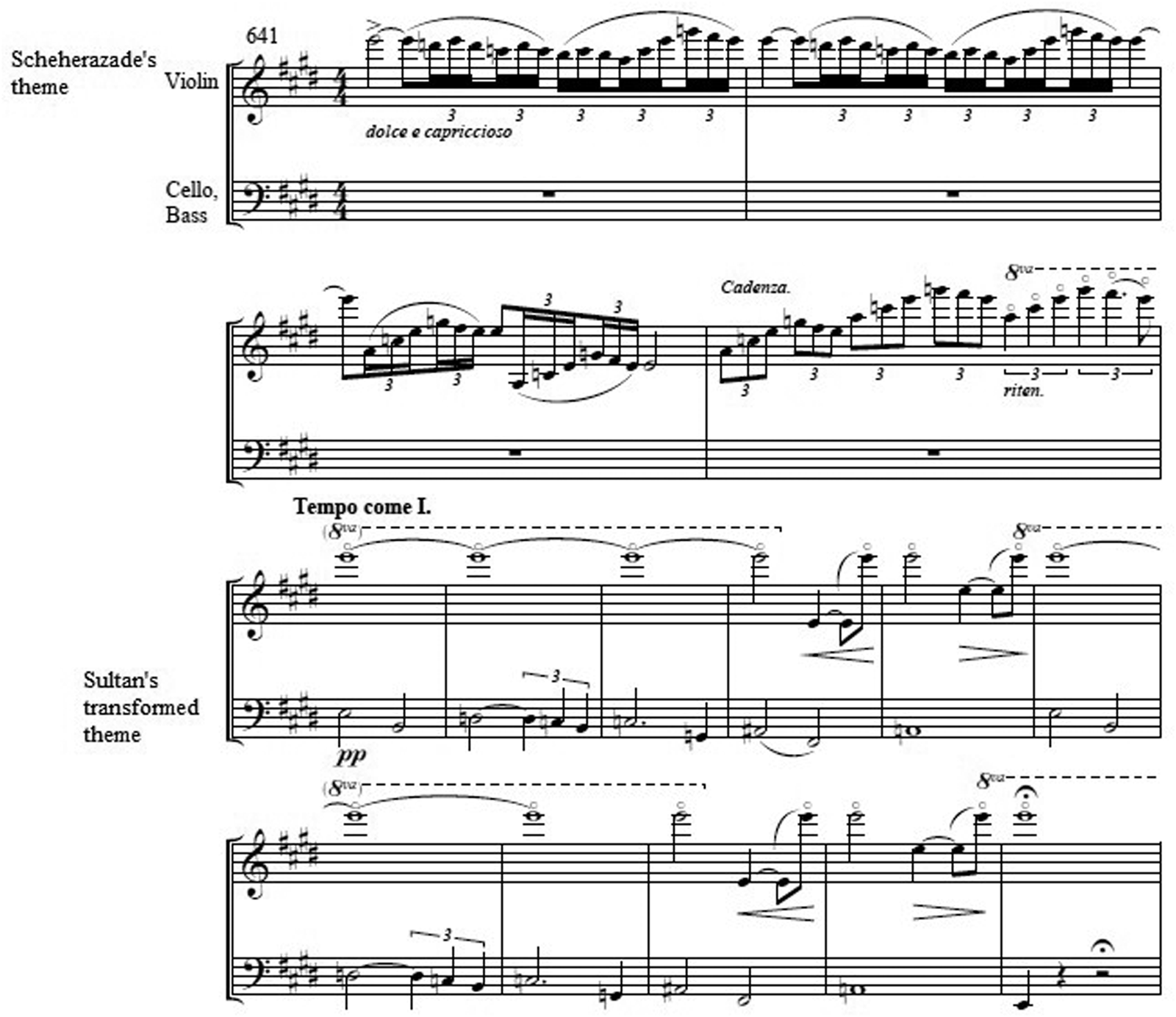

Scheherazade's narrating theme returns throughout the symphony, and her most prominent reappearance occurs near the end of the fourth movement. At the end of her final cadenza, she sustains a high E, overlapping with a new statement of the Sultan's theme. The Sultan is now drastically subdued; his texture is reduced to cello and bass, now pianissimo, and his initial volatile rhythm and accents are now calm. This thematic treatment suggests that the persona of Scheherazade overcomes the Sultan and transforms his violent nature, reflecting the empowered ending of One Thousand and One Nights (Example 3).Footnote 36

Example 3. Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, fourth movement, Scheherazade's theme overlapping and transforming the Sultan's theme, mm. 641–55.

Scheherazade's ornamented arabesque line is a prominent exotic marker, and additional signifiers of exoticism pervade the piece: distinctive and accented rhythmic patterns, quick chromatic ornaments decorating the melody, gapped scales, and colorful harmonies.Footnote 37 The orchestral instruments are at times employed to sound foreign, highlighting woodwind instruments and percussion instruments, including tambourine, snare drum, and triangle.Footnote 38 The programmatic movement titles referencing One Thousand and One Nights contribute to the piece's exoticism, evoking the Arabian world of the folk tales. The indicators of femininity and exoticism in Scheherazade's persona guide listeners to construct a story around the suggested characters and events and recognize the narrative potential of Scheherazade's empowerment. Those familiar with the effects of the tropes and allusive musical representations of Scheherazade possess an important context for understanding the identities and narrative evoked in Scheherazade.2.

A listener's interpretation of Scheherazade.2 may be further influenced by familiarity with John Adams's other works and their socio-cultural and political implications. Many of Adams's compositions, particularly his operas, invoke historical figures and controversial social issues, inviting the audience to reflect on resonances beyond the musical context. For example, Adams's opera The Death of Klinghoffer (1991) incited critical commentary regarding his musical characterization and portrayal of Palestinian identity.Footnote 39 The Gospel According to the Other Mary (2012) and Girls of the Golden West (2017) both represent projects in which the characters and plot engage with themes of gendered and ethnic marginalization and envoicement. Recognizing these issues implicated in Adams's musical projects gives listeners a general framework for approaching his compositions.Footnote 40

Furthermore, scholars have noted Adams's tendency to mythologize his operatic characters, portraying and describing them as archetypes.Footnote 41 For example, discussing his collaboration with Peter Sellars to create Nixon in China (1987), Adams explained their project's ability to “lift the story and its characters, so numbingly familiar to us from the news media, out of the ordinary and onto a more archetypal plane.”Footnote 42 Richard Taruskin further explores this line of thought, critiquing the practice as he describes the main characters of the opera and their transformation into “mythical representations of their countries—naively idealistic young America and ancient, visionary China.”Footnote 43 Listeners of Scheherazade.2 might recognize this kind of treatment in the dramatic symphony, finding a musical archetype of “Scheherazade” entangled with issues of identity and essentialization in the programmatic representation of narrative and identity.

The programmatic instrumental medium of Scheherazade.2 is significant as listeners map their anticipatory notions onto the musical events, interpreting Scheherazade's persona and imagining her experiences in the symphony. Adams's Scheherazade is set against the full orchestra, facing opposition from all sides. Rather than reappearing as a consistent melodic motif, Scheherazade's persona is distinguished by the prominent timbre and virtuosity of the solo violin, evoking her subjectivity. The violin's initial entrance begins with an expressive sustained high D, then flows into a sinuous melody with acrobatic leaps. Her triplet figures and sustained notes obscure the meter and rhythm, perhaps representing a non-conformity to metric order and dominant power. She is accompanied gently by soft sustained chords in the strings and brief gentle gestures in the cimbalom, celesta, harp, and viola, highlighting the solo violin's voice (Example 4).

Example 4. John Adams, Scheherazade.2, first movement, solo violin's initial appearance suggestive of Scheherazade's persona, mm. 14–22.

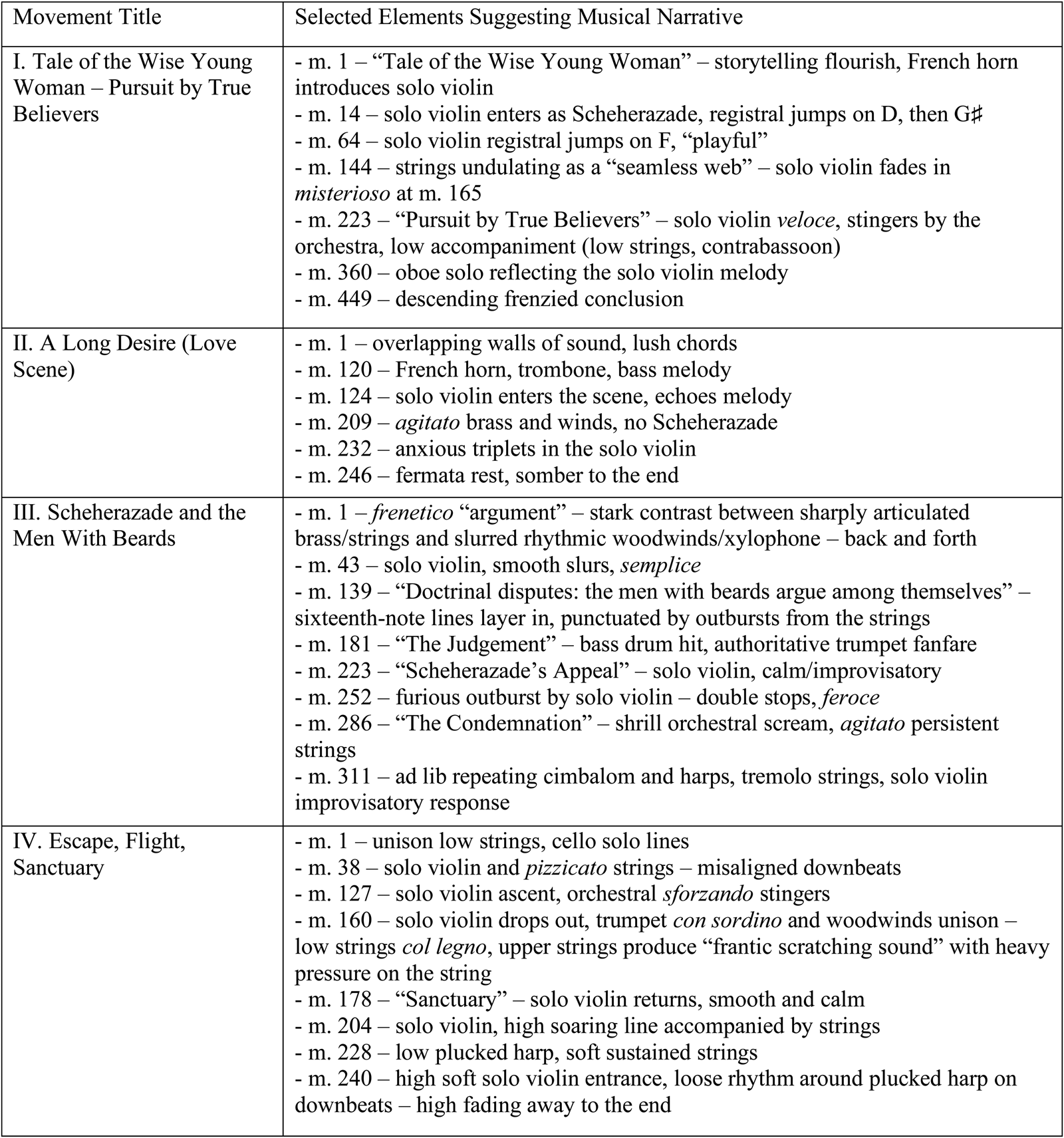

Other characters in the narrative—suggested at times as individual instruments or small ensembles—emerge in a distinctive manner. It is largely left to the listener to imagine how Scheherazade's interactions with these characters might play out, based on programmatic clues and musical expression. As Figure 1 shows, distinctive musical elements lend themselves to potential narrative interpretation emerging from traditional topical and hermeneutic analysis informed by program notes and Adams's specific descriptions in the score. The violin's rhythmic outbursts through the remainder of the first movement may indicate Scheherazade's agitation in the face of orchestral enemies; who are the enemies, and what is the nature of their abuse? In the second movement, “A Long Desire (Love Scene),” overlapping walls of sound construct a lush atmosphere, a love scene from which Scheherazade is at first absent. What kind of “love scene” is this, and what does Scheherazade encounter when she finally enters? Who is Scheherazade's lover, and what tenderness and violence are present?Footnote 44 The third movement, “Scheherazade and the Men with Beards,” introduces a growing animosity, with an even more pronounced disparity between the violin and the rest of the orchestra. The movement begins with stark segmentation between two groups: sharply articulated statements by the strings and low winds juxtaposed against slurred bubbling rhythmic retorts in the higher woodwinds and xylophone. What is the nature of their argument, and what is Scheherazade saying when the solo violin enters with smooth, calm legato lines?

Figure 1. Narrative structure of Scheherazade.2 Footnote 45

The ending of Scheherazade.2 leaves room for listeners to interpret Scheherazade's fate. Adams's program suggests that Scheherazade achieves a successful “Escape, Flight, and Sanctuary,” but the music and program do not clearly indicate the nature of this sanctuary or why this particular outcome “must be the archetypal dream.” The solo violin is foregrounded: free, flowing, and solemn. She is accompanied only by sustained strings, low plucked harp, and gentle percussion rolls, with the bulk of the orchestra absent (Example 5). Some may hear the violin's narrative role overcoming the orchestral counterpart and understand the event as an absolute victory for Scheherazade. The majority of the orchestra falls away, spotlighting the violin and suggesting Scheherazade has left the enemy behind. As in her initial entrance, her rhythmic figures in this final statement obscure the meter, and her articulations rarely coincide with the plucked harp, perhaps indicating a sense of defiance. Her final notes, D-flat and E-flat, are an octave higher than her opening D, perhaps representing an elevation of empowerment. Other listeners, however, may interpret the story as incomplete, sensing only a temporary sanctuary while the threat remains. Still others may understand the ending as an illusion, imagining that Scheherazade does not actually succeed in her search for safety but merely dreams of it. Scheherazade's interactions with programmatic representation and musical tropes suggest different interpretations, each of which carry broader socio-political and cultural implications.

Example 5. Adams, Scheherazade.2, fourth movement, Scheherazade's final monologue, mm. 252–63.

Accepting Scheherazade's identity as a Middle Eastern woman, as indicated in the program and music of Scheherazade.2, bears significant implications for a listener's interpretation of the story and its relevance to a broader socio-political context. Adams's construction of identity in Scheherazade.2 utilizes programmatic suggestions and musical tropes in unique ways, creating a representation that provides certain details while leaving space for listeners to interpret Scheherazade's subjectivity individually. The programmatic descriptions and intertextual connections to One Thousand and One Nights and Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade indicate that Scheherazade is a Middle Eastern woman. Her gender is referenced explicitly in Adams's program, her femininity musically reinforced by the violin's virtuosic melodies and lush timbre. A Middle Eastern ethnicity is less clearly delineated, suggested through the titular allusion to One Thousand and One Nights. Furthermore, Adams's suggestive program notes implicating “true believers” and religious zealots (“men with beards”) carry an Islamic connotation in the context of the United States post-9/11.

Musical evocations of exoticism, most prominent in the cimbalom, reinforce a Middle Eastern identity for Scheherazade. Listeners interpreting these suggestions may perceive Scheherazade.2 as a piece participating in the negative appropriative implications of exoticism. However, while recognizing this problematic engagement, listeners may also perceive a subversive effect to the exotic referents in a contemporary context. In his discussion of musical exoticism in the global age (c. 1960 to today), Ralph Locke describes ways in which recent applications of exotic tropes carry different meanings in the context of globalization and postmodern ideology. While the conflation of “Otherness” (following Said's ideas of orientalism) evoked in traditional exoticism reinforces stereotypes and prejudices, exoticism in this postmodern context can instead “challenge those prejudices.”Footnote 46 As Locke proposes, contemporary applications of exoticism reflecting a postmodern perspective and a globalized musical palette may suggest that, in these instances, composers “are using exoticism to try to kill off exoticism.”Footnote 47 For example, Adams's blatant use of the cimbalom in his postmodern composition arguably subverts the conventional exoticizing tropes, challenging the marginalizing actions taken by Western producers of cultural art. In this case, Adams's exotic evocation can be interpreted as a statement against the reductive suggestions of traditional musical exoticism; his music implicitly critiques the ways in which the canon of European orchestral music and Western cultural art forms have been complicit in colonialism and structures of gender oppression.

Applying a feminist orientalist critique reveals how, through the programmatic and musical representation of Scheherazade's essentialized Middle Eastern identity, Scheherazade.2 in some ways perpetuates traditions of orientalizing exploitation while also challenging those essentializing stereotypes. Revisiting Adams's commentary clarifies the complexity of the music's feminist orientalist effects. Adams's specific examples of the women in Tahrir Square and Tehran and his list of “any number of countries—India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, wherever” effectively evokes a conflated “East” as the location of misogyny and violence. He then continues to clarify that these examples of violence “certainly aren't exclusive to the Middle East—we see examples, if not quite so graphic nonetheless profoundly disturbing, from everywhere in the world including in our own country [United States] and even on our own college campuses.”Footnote 48 In his statement, Adams acknowledges a worldwide issue of gendered violence while citing Middle Eastern examples. By explicitly drawing attention to the universal presence of misogyny, Adams's comment may carry subversive potential, challenging the essentializing “Othering.” Rather than foregrounding the programmatic conflation of an essentialized “Other,” the universal angle of Scheherazade.2 may open space for misogyny to be recognized and confronted around the world. However, by highlighting specific countries in the Middle East, Adams nevertheless reinforces a connection between these regions and practices of violent oppression. By first asserting the issues of misogyny in the Middle East, Adams's claim to similar problems—“if not quite so graphic nonetheless profoundly disturbing”—in the United States is arguably made more palatable to the Western audience, but it fails to offer transnational reparation. The rhetoric of this message, even while couched in progressive rhetoric, effectively reinforces Western superiority while further marginalizing the “Other,” projecting the source of misogyny and the more graphic examples of violence onto the Eastern subject. Combined with the ambiguous use of musical exoticism, this programmatic comment shapes a frame of reference through which audiences may hear and interpret this piece as a continuation of orientalizing and appropriative discourse.

Another facet of the feminist orientalist critique of Scheherazade.2 implicates John Adams's agency as the piece's composer. Different articulations of his subject position range from “white savior” to “race and gender traitor,” imbuing his role with both problematic and reparative implications. Scheherazade.2 tells a musical story of a woman's intimate experiences fabricated by a white U.S. American male composer, presenting the problem of appropriation. By attempting to tell the story of a victimized woman who is racialized as “Other,” it could be argued that Adams positions himself as a “white savior,” adopting an authorial voice that contributes to the marginalizing implications of feminist orientalism. As Gayatri Spivak notes, the subaltern group, defined by its difference from the dominant group, is denied the voice-consciousness to know and speak for itself.Footnote 49 Through this perspective, Adams's authorial voice in Scheherazade.2 prevents Scheherazade's empowerment by essentializing the subaltern and the feminine, erasing her agency by constructing her story through his own musical representation. While his program denounces misogyny, his appropriation of the female voice effectively operates as another form of oppression and perpetuates the issues he claims to address.

However, a perspective considering the potential for reparation allows that Adams's privileged position as a white U.S. American male composer does not necessarily disqualify him from commenting on issues of marginalization. Recognition of Adams's support for the literary, musical, and real-world Scheherazade figures confronting misogyny indicates that Adams demonstrates a traitorous identity. In her discussion of standpoint theory, Sandra Harding identifies “traitorous” contradictory identities in members of a dominant group who advocate for members of a marginalized group: “male feminists; whites against racism, colonialism, and imperialism; heterosexuals against heterosexism; economically over-advantaged people against class exploitation.”Footnote 50 Such individuals defy expectations that they adhere to the social scripts of the dominant group of which they are members and use their power to challenge the marginalizing actions of fellow members of the dominant group, making them “traitors” to that group. By using his privilege as an educated white male composer, Adams is, to some degree, able effectively to give voice through his music to women facing oppression and abuse, as well as call out problematic Western projects that perpetuate misogynistic practices.Footnote 51

Recognizing the feminist orientalist implications of Scheherazade.2 allows the listener to parse the complexities of perspective, agency, and meaning. The ambiguity inherent in Adams's program music does in fact broaden the applicability of the story in a productive way, while also to an extent reinscribing the stereotypes and oppression it seeks to confront. By providing an unfixed narrative, Scheherazade.2 creates space for cultural diversity and recognition of different forms of oppression to manifest in each individual's interpretation. While to some degree participating in essentializing discourse, the recognition of universal misogyny presented in Scheherazade.2 opens up a conceptual space for women of different races and ethnicities to confront misogyny in their own contexts, filling in details according to experience, and encouraging listeners to consider other stories shaped through other perspectives. Through this approach to understanding Scheherazade.2, listeners can acknowledge and strive to overcome its problematic implications by instead pursuing ways to share and interact with the piece in ways that realize its potential for reparation.

Modes of Reception and Interpretation

There are different modes of engaging with the conceptual space of Scheherazade.2, shaped through the unique combinations of physical space, human bodies, and material elements of mediation. Experiencing the music in live performance and experiencing the music through recording affect the listener's impressions in different ways. When listening to the recording released by Nonesuch Records, the listener hears a balanced ensemble, with each instrumental part clearly projected through the speakers or earphones. Above this equilibrium, the violin consistently emerges over the orchestra. This textural separation may contribute to positive interpretations of the empowered woman, supported by aural indications of Scheherazade overcoming the orchestral oppression. However, while the sound is balanced, it is also compressed and physically removed, perhaps making the experience less powerful and minimizing Scheherazade's actions. In a live performance, the acoustics may not be balanced, and certain instruments may overwhelm others at various points in the piece. The solo violin may not always seem as loud and strong as it might in the recording, and this fluctuation of the violin's prominence affects the perceived narrative. The physical presence of the ensemble is also significant; the audience feels the sound vibrate around the hall and through their bodies, and seeing the orchestra surround the soloist and conductor may provide a sense of the oppression Adams proposes.Footnote 52

The soloist's physical presence is especially significant to the audience's interpretation. Adams composed the violin part embodying Scheherazade specifically for his friend and colleague, Leila Josefowicz (b. 1977), whose performances lend tangibility to the interpretation of Scheherazade Adams proposes. Writing on opera performance, Carolyn Abbate emphasizes the visual significance of watching the soloist, highlighting the way in which the opera singer brings the art to life and assumes the position of creative expression. Abbate argues that while an audience visually and aurally stares at a female performer (seemingly reinforcing the objectification of women), the female performer's active performance before the passive audience actually subverts the gender roles and empowers her, challenging the male gaze.Footnote 53 Abbate's conceptualization of subverting this dichotomy applies well to live performances of Scheherazade.2. Seeing the physical performance of the violinist (at present, likely Leila Josefowicz) enhances the music's drama and emotion.Footnote 54 Josefowicz is renowned for her emotive and virtuosic performances of new music, and her role as soloist fuels this piece's expressive power.Footnote 55 The visual dimension of Josefowicz's performance lends itself directly to interpreting Scheherazade's story; her facial expressions and body movements give the impression that she is literally interacting with other characters and experiencing the dramatic action (Figure 2).Footnote 56 Although the audience observes the performance, Josefowicz assumes the active, subjective role; in this sense, Josefowicz is able to embody Scheherazade effectively and thus achieve empowerment for her. Many media reviews of Scheherazade.2 performances comment on Josefowicz's powerful realization of Scheherazade's solo violin role. For example, a review in The New York Times praises Josefowicz's “stunning performance, by turns commanding and vulnerable, slashing and sensual.”Footnote 57 In his review of the Seattle Symphony's performance, Thomas May offers a similarly laudatory assessment:

On a purely visual level, Josefowicz's facial expressions and body language were as fascinating as those of a brilliant actress or singer whose character has to fight for her life. And her musicianship is one of a kind — completely in tune with the shifting emotional landscape of Adams’ harmonic musical language, which is complex, but not in the over-intellectualized, 20th-century avant-garde way. Its complexity reflects first and foremost the emotional complexity of the musical content. Josefowicz brought all these layers to life.Footnote 58

Figure 2. “Photo Gallery,” Leila Josefowicz, photo by Chris Lee, accessed February 14, 2019, https://www.leilajosefowicz.com/photo-gallery/.

Seeing Josefowicz also affects understandings of Scheherazade's identity and the feminist orientalist implications of Scheherazade.2. The fact that a Canadian-American female violinist assumes the role of Scheherazade reinforces the perspective recognizing universal misogyny, undermining stereotypes of Middle Eastern violence and illustrating that misogyny is an issue worldwide. Seeing the white female violinist (and perhaps seeing the white male figure of John Adams conduct) may encourage a more self-aware and self-critical response from the Western audience. In an interview with the author, Josefowicz described her perspective on how her own identity and that of Adams might be understood:

[John Adams] can't help that he's white, nor can I. He can't help that he's male, I can't help that I'm female. It's sort of like, let's focus on the quality of what's being done, the people that are delivering the quality, who are they? We're not judging, choosing, in my head and in his head, we're not basing anything on whether someone's a woman or whether someone's a man or African American or what. I mean, straight, gay. We're so self-consciously categorizing everything now… There are so many gray areas of this that make this such a complex issue. For someone, whoever, to come forward and make a generalization of any kind probably is not right. This is far too complex an issue for that.Footnote 59

Her statement reflects the complexities of American orientalism and feminist orientalism. Her words condemn oppression and seek to deconstruct the power dynamics of identity politics, positioning Josefowicz as a race traitor who challenges the narratives that sustain the elevation of white voices. However, like Adams, Josefowicz's privileged position—a Western woman, well-trained, and highly regarded as a performer—places her in a dominant group telling the story of the oppressed Scheherazade. Following the programmatic projection of oppression onto the Eastern subject, Josefowicz's embodiment of Scheherazade in some ways problematizes her participation in the Scheherazade.2 project that arguably appropriates the voice of an “Othered” woman and reinscribes Western dominance.

Experiencing the music through the recording presents a different set of implications, replacing the physical presence of the soloist and orchestra with the materiality and imagery of the album. For listeners of the Nonesuch recording, the visual component of the CD album cover art contributes interesting and significant visual cues (Figure 3). Without further context, the listener will perhaps perceive the image of an unknown veiled Middle Eastern woman as a representation of Scheherazade. However, examining the artwork's origin reveals a deeper story. This piece, titled “I Am Its Secret,” is part of a photographic series called “Women of Allah” created in the 1990s by Iranian-born artist Shirin Neshat.Footnote 60 Her project comments on the changing cultural landscape in the Middle East following the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979, exploring the complexities of women's identities and social roles. “I Am Its Secret” is a photograph of Neshat herself. The image contains rich symbolism—in the veil, the penetrating stare, and the bulls-eye target pattern—challenging the male gaze and the generalized assumption that reads veiling as a signifier of oppression. Even the Farsi script, which could merely serve to evoke a sense of the Middle East, carries deeper meaning as a transcription of poetry by Forough Farokhzad.Footnote 61

Figure 3. Nonesuch album cover of John Adams's Scheherazade.2: LP package design by John Heiden for SMOG Design. Front cover image: “I Am Its Secret,” Shirin Neshat, 1993. Image used with permission from Nonesuch Records, Inc.

Seeing Neshat's image on the album cover adds layers of meaning to Scheherazade.2 and contributes to the feminist orientalist critique. To an uninformed Western listener perceiving the image as an anonymous Middle Eastern woman, this visual component may suggest essentialized exoticism. The image of a Middle Eastern woman reinforces the programmatic commentary that projects the problems of misogyny onto the “Other.” On the other hand, to the listener who sees the image and already knows or proceeds to learn about Shirin Neshat and her artwork, the album cover conveys the powerful statement of an Iranian woman defying oppression on her own terms. In this sense, the album cover makes space for Scheherazade.2 to tell a genuine story of empowerment instead of a generalized construal, but does not inevitably do so.

The reception of Scheherazade.2 demonstrates the various interpretations that arise from different encounters with the music. Media reviews of the piece typically offer narrative descriptions, telling variations of a story constructed from the program notes and commenting on various aspects of the music. These reviews reflect the difficulty of locating a fixed narrative in the piece, with the ambiguity leaving room for media writers to tell their own stories and prioritize certain aspects over others. Reviews of the Nonesuch recording describe the quality of Adams's composition and Josefowicz's performance. Only brief comments indicate that these reviews refer to the album and not a live performance. In Tom Huizenga's NPR review, he describes the piece “unfolding in a potent drama, masterfully illuminated by conductor David Robertson and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra,” and Andrew Farach-Colton positively states that “the recording is beautifully balanced.”Footnote 62

Other media reviews commenting on performances by major ensembles follow a similar approach, largely offering praise but also raising concerns about the piece's broader implications. The articles analyzed here voice the perspectives of critics writing for the U.S. media, and to some extent they reflect the thoughts of individual listeners and general audiences. As such, these reviews present a largely white, Anglo-American viewpoint. In her review of a performance by the Seattle Symphony, Claire Biringer approaches Scheherazade.2 as an educator of Western music history, emphasizing the “dead white male” composers that dominate the canon. While Adams is not dead, Biringer recognizes his privileged position contributing to the canon of white male composers; she notes the difficulty of accepting “the fact that symphonic music in 2016 remains in a place where female characters are still primarily given life by male composers.”Footnote 63 However, she asserts that Scheherazade.2 is a sign of progress rather than a problematic proliferation of gender imbalance. While recognizing that “classical music is still a man's world,” Biringer describes how the landscape is slowly shifting to one where females are experiencing “small victories: the joy of new music, an empowered female character, and John Adams, composing a gender-conscious rendition of a centuries-old tale.”Footnote 64 She views Adams as a sympathetic white male composer seeking to use his privilege to advance minority voices, a positive and perhaps necessary agent in bringing the musical Scheherazade to life.

Rebecca Wishnia echoes this sentiment by foregrounding the advocacy of women composers; she observes that since no female composers were featured in the San Francisco Symphony's regular season that year (2016–17), it was fortunate “that this man [Adams] cares enough to speak” on their behalf.Footnote 65 More recently, in his review of a performance by the Boston Symphony, Jeremy Eichler seems to view Adams's composition as more problematic, but controversial in a way that raises awareness of the problem. He suggests that while Adams may contribute to the proliferation of the “white male” canon, the message of Scheherazade.2 draws attention to the neglect of female composers and supports the progressive perspectives of those seeking to address this imbalance:

There is now for instance more discussion than ever before about why the seasons of every symphony orchestra in the land, and even many new music festivals, are dominated by the music of male composers. Clearly when the next Scheherazade is written, it will be time for a woman to tell her own story.Footnote 66

These reviews draw attention to the various facets of Scheherazade.2 implicated in this feminist orientalist critique. The reviews suggest that Adams's composition, though the product of a masculine imagination, may pave the way for female voices to be heard more prevalently in the Western musical world. However, little attention is given to the ethnic, racial, and cultural implications of Adams's project. Eichler finds “some larger conceptual issues unresolved,” wondering how Adams “simultaneously trades on the exoticism of this legend… while at the same time critiquing it from within a reimagined modern frame.”Footnote 67 However, while Eichler finds this troubling, most reviewers simply comment on an “exotic flavor” without delving deeper into the cultural issues it presents. While Scheherazade.2 dramatizes a message of empowered resistance that is productive for Western feminist contexts, the orientalizing discourse through which this message is conveyed may reinscribe a colonialist “Othering” of the Middle Eastern woman. By foregrounding Western feminist ideals, such discourse marginalizes and impedes the productivity of Middle Eastern and transnational feminisms, disrupting the potential for reparative work in a global context. Recognizing and addressing the feminist orientalist implications of Scheherazade.2 can contribute to revealing similar tendencies underlying other cultural projects on a broader scale. Drawing more attention to these wide-ranging issues can work towards balancing the power dynamics in both the musical canon and performance institutions as well as in social and political situations on a broad scale.

Conclusion

Exploring the changing relationships and meanings of Scheherazade.2 through a feminist orientalist critique illuminates the project's range of implications. In some cases, the reparative dimensions may be foregrounded, allowing the music and its story to promote productive advocacy and change; in other cases, the orientalizing tendencies are highlighted, problematizing the piece's essentialized representations and appropriated narrative. Recognizing these implications and their real-world potential invites critical response and initiative. By taking actions that will further foreground the reparative potential and further diminish problematic reinscription, feminist orientalist critique can move towards effecting tangible change. As discussed throughout this article, the agency of each person involved with Scheherazade.2 bears significance, giving each person the opportunity to turn the music into a positive force of redress.

Reparation may be achieved through framing the piece in contexts that acknowledge and counteract essentialization. Josefowicz's interview response explains her conception of the dynamic influences that shape interpretation and the potential for further shifting of meaning and effect:

John [Adams] has a very special way of really thinking about world issues and uses these thoughts and these ideas for inspiration for his composition… [Scheherazade.2] came right before the whole “Me Too” thing, which is crazy… it is a universal issue we are far from overcoming… He wanted to, I think… de-romanticize this whole story. Oh, the Arabian Nights and the Thousand and One Nights, and she seduces the king, well yeah, why? Why does she do that? Not because she's a seductress per se, she does it to save her own life. And how many came before her that didn't have the gumption, the courage, the instincts of survival that she had, that's what he wanted to focus on, not the romanticized version of some seductress to the king… [The ending] is something that is left to the listener, and I like that, because it's, you hear it the way you want to hear it and there's no wrong way to hear it. There's never a wrong way to hear music in general. So it's kind of like life right now, there aren't really clear answers, are there? That's what this is also like, and again, it's de-romanticizing, which is so important. De-romanticizing this sort of, happily-ever-after sort of mentality, which is not real. Things can end well I suppose, in various ways, but change is constant, right?Footnote 68

Josefowicz highlights the importance of de-romanticizing the story of Scheherazade, but the next step is to de-essentialize the story. Moving beyond the Western agenda implicated in Scheherazade.2 can pave the way to reparation on a global scale. Josefowicz's comment about the Me Too movement focuses on the Western feminist agenda, highlighting the viral social media campaign that grew as a hashtag to counter sexual harassment and assault in the United States.Footnote 69 By consciously making connections to similar movements in other countries, the reparative intention may be more fully realized. Scheherazade.2 may then truly present a conceptual space that affirms different stories of oppression and empowerment from around the world and encourages listeners to consider and share their own experiences and those of others.

Josefowicz is a prominent figure of Scheherazade.2, offering both musical interpretation through performance and verbal interpretation through commentary. Critics largely acclaim the powerful performance of Josefowicz, raising the issue of the sustainability of Scheherazade.2 beyond her presence; the piece would function differently if another violinist assumed the solo role, perhaps especially if violinists of different genders and ethnicities were to take on the part.Footnote 70 This idea demonstrates the power of each performer and conductor to influence how Scheherazade's story occurs through their distinct musical interpretations and communication with audiences. As the composer and sometimes-conductor, John Adams also offers influential perspectives. His role is constantly fluid as he conducts his composition with various ensembles (or as others conduct it), as he provides commentary on his role as composer, and as audience members and critics respond to his musical actions and commentary. Adams's authorial voice carries a certain power, giving him the opportunity to expound upon the piece's reparative dimensions. In doing so, he can promote Scheherazade.2 and other relevant cultural projects in ways that look beyond the Western context to transnational healing. For instance, as the feminist orientalist critique contained in this essay has revealed, Adams's reference to cases of victimized Middle Eastern women in the media contributed to the reinscribing projection of oppression on the East. By discussing other worldwide contemporary events in relation to the story of Scheherazade.2, Adams's commentary may work to break down the binary and contribute to genuine advocacy and activism on a global scale.

Concert halls convey different ideological perspectives, as performances of Scheherazade.2 interact with each institution's broader programming and patronage. Programming Scheherazade.2 may disrupt trends of traditional canonic adherence or promote engagement with modern compositions. In this socio-cultural context, the musical communities surrounding each concert hall and orchestra also carry meaningful agency. The contextual possibilities arising from the concert hall setting demonstrate the variability of meaning of Scheherazade.2, within a single performance and across many performances over time. The programming of a concert influences how the audience will perceive Scheherazade.2; as noted previously, programming Scheherazade.2 alongside Rimsky-Korsakov or other pieces evoking nineteenth- or twentieth-century exoticism reinforces the orientalizing reinscription of the “Other.” Instead, positioning Scheherazade.2 with other compositions drawing attention to gender and ethnic power imbalances may allow the music's message to achieve its reparation. For example, breaking down generic borders and introducing Scheherazade.2 alongside pieces such as MILCK's “Quiet” or the collaborative project “A Thousand Hands: A Million Stars” would engage artists, performers, and audiences in a broader project, creating possibilities for reparative responses through the shared personal stories of pain and survival.Footnote 71 As performers, conductors, and music institutions take steps toward reparation, the agency of the individual listener again takes on a more active role as each individual's unique interpretation and application of the music's message contributes to unlocking the reparative potential of Scheherazade.2.

Scheherazade.2 conveys a meaningful message about contemporary power dynamics complicated by implications of feminist orientalism. Different dimensions of the project are foregrounded in different situations, impacting the story understood by each listener and affecting the music's interaction with the unique social dynamics of each community. Despite the appropriative and orientalizing tendencies, Scheherazade.2 should not be wholly dismissed. Rather, as I have argued, recognizing the piece's paradoxical nuances gives us the opportunity to overcome problematic implications and promote reparative possibilities. By capitalizing on the elements of global advocacy and reparation, John Adams and Leila Josefowicz, along with every conductor, performer, listener, and scholar involved with Scheherazade.2, carry the potential to create meaning with this piece and effect positive change. We can realize the reparative potentials of Scheherazade.2 through our critical responses and conscious actions, pursuing a broader dimension of genuine transnational social advocacy that could empower countless Scheherazades.

Appendix 1

Select Performances and Reviews of Scheherazade.2

The Scheherazade.2 Performance Records page provided on the Boosey & Hawkes website includes the dates, ensembles, conductors, and locations of most of the performances listed below.Footnote 72 This appendix supplements the Boosey & Hawkes list, adding the repertoire performed alongside Scheherazade.2 in U.S. concerts and select media reviews reflecting on the respective performances. It is worth repeating here that Leila Josefowicz has performed as the soloist in all these performances.

March 26–28, 2015—World Premiere

Ensemble: New York Philharmonic

Conductor: Alan Gilbert

Location: Avery Fisher Hall, New York, NY, United States

Programmed Alongside: Anatoli Liadov, The Enchanted Lake; Igor Stravinsky, Petrushka

Select Reviews:

– Anthony Tommasini, “Review: John Adams Unveils ‘Scheherazade.2,’ an Answer to Male Brutality,” The New York Times, March 27, 2015.

– George Grella, “Aided by Josefowicz's Fire, Adams Returns to Form with “Scheherazade.2,” The Classical Review, March 29, 2015.

– Russell Platt, “Woman of the World: The Violinist Leila Josefowicz Plays John Adams's Latest Piece,” The New Yorker, March 30, 2015.

April 17–18, 2015

Ensemble: Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Music Hall, Cincinnati, OH, United States

Programmed Alongside: Anatoli Liadov, The Enchanted Lake; Ottorino Respighi, Pines of Rome

Select Reviews:

– Janelle Gelfand, “John Adams’ Powerful Scheherazade for Our Time,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 18, 2015.

– Mary Ellyn Hutton, “Adams’ “Scheherazade.2” Resonates with the CSO,” Music in Cincinnati, April 19, 2015.

May 7, 9, 2015

Ensemble: Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Atlanta Symphony Hall, Atlanta, GA, United States

Programmed Alongside: Anatoli Liadov, The Enchanted Lake; Ottorino Respighi, Pines of Rome

Select Reviews:

– Mark Gresham, “ASO Review: John Adams’ “Scheherazade.2” celebrates an archetype of women,” ArtsATL, May 8, 2015.

– James L. Paulk, “At ASO, Leila Josefowicz is dazzling in John Adams’ ‘Scheherazade.2,’” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution May 8, 2015.

October 15–16, 2015—European Premiere

Ensemble: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, Netherlands

October 29, 2015—UK Premiere

Ensemble: London Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Barbican, London, United Kingdom

January 8, 12, 13, 2016

Ensemble: Finnish Radio Symphony

Conductor: Hannu Lintu

Locations: Konzerthaus, Großer Saal, Wien, Austria

Kongresshaus, Innsbruck, Austria

Grosses Festspielhaus, Salzburg, Austria

February 19–20, 2016—Performances Recorded for Nonesuch Album

Ensemble: St. Louis Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: David Robertson

Location: Powell Symphony Hall, St. Louis, MO, United States

March 2–4, 2016—Australian Premiere

Ensemble: Sydney Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: David Robertson

Location: Sydney Opera House, Sydney, Australia

March 17–19, 2016—U.S. West Coast Premiere

Ensemble: Seattle Symphony

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Benaroya Hall, Seattle, WA, United States

Programmed Alongside: Edward Elgar, Military March No. 3 in C minor; Ottorino Respighi, Pines of Rome

Select Reviews:

– Thomas May, “‘Scheherazade.2’ triumphs at Seattle Symphony,” The Seattle Times, March 18, 2016.

– Claire Biringer, “Scheherazade in a Man's World: Feminism, Classical Music and Scheherazade.2,” Vanguard Seattle, March 30, 2016.

April 14, 2016

Ensemble: Los Angeles Philharmonic

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Walt Disney Hall, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Programmed Alongside: Ottorino Respighi, Fountains of Rome, Pines of Rome

Select Reviews:

– Mark Swed, “Review: Violinist Leila Josefowicz is a powerful storyteller in John Adams’ ‘Scheherazade.2,’” Los Angeles Times, April 15, 2016.

May 4–5, 2016

Ensemble: Toronto Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Peter Oundjian

Location: Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto, ON, Canada

September 2, 2016—Swiss Premiere

Ensemble: Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Victoria Hall, Genève, Switzerland

September 15–17, 2016—German Premiere

Ensemble: Berliner Philharmoniker

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Philharmonie, Berlin, Germany

October 20–21, 2016

Ensemble: Minnesota Orchestra

Conductor: Edward Gardner

Location: Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Programmed Alongside: Hector Berlioz, Overture to Benvenuto Cellini; Maurice Ravel, Second Suite from Daphnis et Chloé

Select Reviews:

– Kathy Berdan, “Minnesota Orchestra Review: Violinist Josefowicz Fascinating in ‘Scheherazade.2,’” Twin Cities Pioneer Press, October 20, 2016.

– Terry Blain, “Violinist Leila Josefowicz Played Like ‘a Warrior Princess’ in Minnesota Orchestra's ‘Scheherazade.2’ Concert,” Star Tribune, October 21, 2016.

November 5–6, 2016

Ensemble: Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich

Conductor: Alexander Liebreich

Location: Tonhalle, Großer Saal, Zürich, Switzerland

December 8, 2016

Ensemble: London Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Barbican, London, United Kingdom

December 9, 2016—French Premiere

Ensemble: London Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Dijon, France

December 10, 2016

Ensemble: London Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Philharmonie de Paris, Paris, France

February 22–25, 2017

Ensemble: San Francisco Symphony

Conductor: Michael Tilson Thomas

Location: Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, CA, United States

Programmed Alongside: Sergei Prokofiev, Romeo and Juliet

Select Reviews:

– Joshua Kosman, “Adams unleashes a powerhouse with ‘Scheherazade.2,’” San Francisco Chronicle, February 23, 2017.

– Rebecca Wishnia, “Sorrow and Strength in John Adams's Scheherazade.2,” San Francisco Classical Voice, February 28, 2017.

March 2, 4, 7, 2017

Ensemble: Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Esa-Pekka Salonen

Location: Symphony Center, Chicago, IL, United States

Programmed Alongside: Claude Debussy, Prélude À l'Après-Midi d'un Faune; Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring

Select Reviews:

– Lawrence A. Johnson, “Josefowicz, Salonen and CSO Deliver Compelling Virtuosity in Adams Premiere,” Chicago Classical Review, March 3, 2017.

– John Von Rhein, “Salonen, CSO Help Deliver a Potent New John Adams Work,” Chicago Tribune, March 3, 2017.

April 17–18, 2017—Japanese Premiere

Ensemble: Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Alan Gilbert

Location: Tokyo Opera City Concert Hall, Tokyo, Japan

October 5, 2017

Ensemble: Iceland Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Daniel Bjarnason

Location: Harpa, Reykjavik, Iceland

March 1–3, 2018

Ensemble: Boston Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Alan Gilbert

Location: Boston Symphony Hall, Boston, MA, United States

Programmed Alongside: Claude Debussy Jeux; Jean Sibelius, En Saga

Select Reviews:

– Jeremy Eichler, “At BSO, hearing anew the legend of Scheherazade,” Boston Globe, March 2, 2018.

– Jeffrey Gantz, “BSO Tells Scheherazade.2 & Other Stories,” The Boston Musical Intelligencer, March 2, 2018.

July 13–14, 2018

Ensemble: Grand Teton Music Festival Orchestra

Conductor: Markus Stenz

Location: Walk Festival Hall, Teton Village, WY, United States

Programmed Alongside: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 6, “Pastoral”

Event: Grand Teton Music Festival

October 25, 2018

Ensemble: Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Concert Hall, Oslo, Norway

November 29–30, December 1, 2018

Ensemble: Cleveland Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Severance Hall, Cleveland, OH, United States

Programmed Alongside: Aaron Copland, Quiet City, Appalachian Spring; John Adams, Short Ride in a Fast Machine

Select Reviews:

– Zachary Lewis, “Cleveland Orchestra gives American music royal treatment with composer John Adams,” Cleveland Advance Local, November 30, 2018.

– Daniel Hathaway, “Cleveland Orchestra with Adams & Josefowicz (Nov. 30),” Cleveland Classical, December 4, 2018.

March 8, 2019

Ensemble: Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Marin Alsop

Location: Strathmore, Baltimore, MD, United States

Programmed Alongside: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade

Select Reviews:

– Simon Chin, “BSO offers two musical portraits of the beguiling narrator Scheherazade,” The Washington Post, March 11, 2019.

September 19, 21, 2019

Ensemble: Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra

Conductor: Ward Stare

Location: Eastman Theatre, Rochester, NY, United States

Programmed Alongside: Mason Bates, “Mothership”; Cindy McTee, “Einstein's Dream”; Steve Reich, Three Movements

Event: KeyBank Rochester Fringe Festival

Select Reviews:

– David Raymond, “David Reviews ‘Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra: Scheherazade.2,’” Rochester City News, September 20, 2019.

September 26–28, 2019

Ensemble: Philadelphia Orchestra

Conductor: John Adams

Location: Verizon Hall, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Programmed Alongside: Maurice Ravel, Alborado del gracioso; Igor Stravinsky, Song of the Nightingale

Re-broadcast on WRTI 90.1 radio on May 10–11, 2020

Select Reviews:

– David Patrick Stearns, “John Adams is Conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in Ravel, Stravinsky—and Himself—in a Journey Worth Taking,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 27, 2019.

– Gregg Whiteside, “The Philadelphia Orchestra in Concert on WRTI 90.1: John Adams and Leila Josefowicz in the Spotlight,” WRTI 90.1, May 4, 2020.

January 11–13, 2020

Ensemble: Oregon Symphony

Conductor: Alexander Liebreich

Location: Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, Portland, OR, United States

Programmed Alongside: Charles Ives, The Unanswered Question; Richard Strauss, Also sprach Zarathustra

Select Reviews of Nonsuch Records Scheherazade.2 album:

– Tom Huizenga, “Review: John Adams, ‘Scheherazade.2,’” NPR, September 22, 2016.

– Andrew Farach-Colton, “Adams Scheherazade.2,” Gramophone.

– Sarah Bryan Miller, “CD Reviews: SLSO Team Makes a Convincing Case for ‘Scheherazade.2,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 21, 2016.

– Robert Levine, “Adams’ Scheherazade.2—A 21st Century Rethinking,” Classics Today.