Inadequate food consumption patterns during childhood and adolescence are linked not only with the occurrence of obesity in youth(Reference Niemeier, Raynor and Lloyd-Richardson1), but also with the subsequent risk of developing diseases such as cancer(Reference Maynard, Gunnell and Emmett2), obesity(Reference Lichtenstein, Kennedy and Barrier3) and CVD(Reference De Henauw, Gottrand and De Bordeaudhuij4) in adulthood. Adolescence is a potentially critical period for body composition in later life and the development of obesity in adulthood(Reference van Lenthe, Kemper and van Mechelen5). This may be due to the hormonal changes regulating appetite, satiety and fat distribution that occur during puberty(Reference Lustig6). In addition, adolescence is a time of dramatic behavioural changes in which children test their autonomy and assert independence from their parents, which may affect both eating behaviours(Reference Lytle and Kubik7) and physical activity(Reference Berkey, Rockett and Field8). Since poor dietary habits in this critical period of adolescence(Reference Dietz9) might continue into adulthood and then become extremely resistant to modification(Reference Lobstein and Frelut10), the establishment and maintenance of a healthy diet early in life is of great public health importance.

Up to now, investigations of adolescents’ dietary intake and eating habits have been carried out in several European countries only on a national or regional level. For example, in Germany(Reference Mensink, Kleiser and Richter11) and Spain(Reference Aranceta Bartrina, Serra-Majem and Perez-Rodrigo12), it was found that adolescents eat less vegetables, fruit, bread and potatoes than recommended, and too much meat (and meat products). In Greece(Reference Yannakoulia, Karayiannis and Terzidou13) and Belgium(Reference Huybrechts, Matthys and Vereecken14), the intakes of energy-dense and low-nutritious foods were high. Moreover in England(Reference Glynn, Emmett and Rogers15) the foods consumed mostly were white bread, fried chips and confectionery.

However, differences in methodology, population groups and age categories make it difficult to use these data for a detailed evaluation of dietary intake among adolescents from a European perspective(Reference Lambert, Agostoni and Elmadfa16). The HEalthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence Cross-Sectional Study (HELENA-CSS) provided for the first time the opportunity to examine food consumption of a large sample of adolescents across several European countries using standardized, harmonized and validated instruments and procedures for the dietary intake assessment.

Therefore, the purpose of the present analysis was to describe and evaluate food consumption among anthropometrically and socio-economically well-characterized European adolescents. Although assessment of food consumption is – especially for children and adolescents – an adequate and moreover practical approach to evaluate and improve dietary habits, there are no generally accepted reference values for the food intake of adolescents. Hence, for the evaluation we used two sets of food-based dietary recommendations for children and adolescents that are designed to translate nutrient-based recommendations into practical, total diet concepts(17), namely the Optimized Mixed Diet (OMD)(Reference Kersting, Alexy and Clausen18) and the Food Guide Pyramid (FGP)(19).

Materials and methods

Study design and population

The HELENA-CSS is a multi-centre investigation that was conducted between 2006 and 2007 in ten European cities (Athens and Heraklion (Greece), Dortmund (Germany), Ghent (Belgium), Lille (France), Pecs (Hungary), Rome (Italy), Stockholm (Sweden), Vienna (Austria) and Zaragoza (Spain)). Detailed information about the study has been reported elsewhere(Reference Moreno, Gonzalez-Gross and Kersting20, Reference Moreno, De Henauw and Gonzalez-Gross21). The main objective of HELENA-CSS was to obtain reliable and comparable data on a variety of nutritional and health-related parameters in a sample of more than 3000 European adolescents (boys and girls aged 12·5–17·5 years)(Reference Moreno, Gonzalez-Gross and Kersting20). Therefore, a random cluster sampling among all classes from all schools in the ten cities was carried out(Reference Moreno, De Henauw and Gonzalez-Gross21). The ethical committee of each city approved the study and signed informed consent was obtained from the adolescents as well as their parents(Reference Beghin, Castera and Manios22).

Data on food intake from Heraklion and Pecs were not available for the current analysis. Furthermore, specific inclusion criteria (complete data on energy and food intakes for 2 d obtained by the HELENA-DIAT 24 h recall and data on anthropometry) were defined for the analysis and fulfilled by 2330 adolescents. Among these, adolescents with plausible dietary recalls were ascertained by relating their reported total energy intake to their BMR, as described below. Hence, the sample analysed here included 1593 adolescents (54 % female).

Dietary intake assessment

Dietary intake data were obtained using a self-administered, computerized, 24 h recall, named HELENA-DIAT, which was based on Young Adolescents’ Nutrition Assessment on Computer (YANA-C)(Reference Vereecken, Covents and Matthys23) and validated in Flemish adolescents and then improved and culturally adapted by adding national dishes to reach a European standard(Reference Vereecken, Covents and Sichert-Hellert24). The program is organized in six meal occasions and the participants can select from about 400 predefined food items and are free to add non-listed foods manually. Special techniques are used to allow a detailed description and quantification of foods, e.g. pictures of portion sizes and dishes. Amounts eaten could be reported as grams or by common household measures. After a short introduction by a trained researcher, the adolescents completed the HELENA-DIAT 24 h recall by themselves during school time while research staff were available in the classroom to assist the adolescents if necessary. They completed the HELENA-DIAT twice on non-consecutive days within a time span of two weeks, to achieve information closer to habitual food intake than assessing food intake on consecutive days.

Since the purpose of the data analysis was to describe food consumption of European adolescents in a detailed and practice-oriented way, we used the forty-five predefined food groups to which each consumed single food item had been assigned in HELENA-DIAT (e.g. mozzarella is assigned to the HELENA food group ‘cheese’). The intake (g/d) of each food group and total daily energy intake (kJ/d) were calculated for each participant from the mean of the two respective 24 h recalls. Total daily energy intake was used to exclude potentially implausible recalls by comparing it to the BMR estimated with the equations of Schofield(Reference Schofield25). Using the well-acknowledged approaches of Goldberg et al.(Reference Goldberg, Black and Jebb26) and Johannson et al.(Reference Johansson, Solvoll and Bjorneboe27), overall, 574 (43 % male and 57 % female) adolescents were assigned as under-reporters and 163 (61 % male and 39 % female) adolescents were assigned as over-reporters. Both under- and over-reporters were hence excluded from the analysis.

To compare the adolescents’ food intake with age-specific food-based dietary guidelines we used the total diet concepts of the OMD for children and adolescents living in a European country, developed by the German Research Institute of Child Nutrition(Reference Kersting, Alexy and Clausen18), and the dietary guidelines for Americans, the FGP, developed by the US Department of Agriculture(19).

The OMD recommendations are categorized into eleven food groups, and the forty-five HELENA food groups were assigned to these, e.g. the HELENA food group ‘cheese’ was assigned to the OMD group ‘milk and milk products’. If a HELENA food group could not be assigned to any OMD group, it was allocated as ‘others’, e.g. meat substitutes and vegetarian products (Table 1). Recommended food group intakes are given in g/d and are sex- and age-group-specific based on the respective recommended energy intake. For this analysis we used the OMD recommendations for boys and girls in the age groups 13–14 years and 15–18 years(Reference Kersting, Alexy and Clausen18).

Table 1 Categorization of the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescents) food groups into the foods groups of the Optimized Mixed Diet (OMD)Footnote * and the Food Guide Pyramid (FGP)Footnote †

* See Kersting et al. (2005)(Reference Kersting, Alexy and Clausen18).

† See US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture (2005)(19).

The FGP is structured into six food groups to which the HELENA food groups were assigned or were respectively allocated as ‘others’ (Table 1). The FGP recommendations are stated as daily numbers of servings from each food group(19). What counts as a serving is specified separately and exemplarily for several foods in each group by means of ounces or household measures such as cups or teaspoons, e.g. 1 serving of milk products is equal to 1 cup of yoghurt(28–33). To derive food-specific weights for the respective serving sizes (e.g. cups)(Reference Cleveland, Cook and Krebs-Smith34), we used data on the number of grams per household measure in the ‘MyPyramid Equivalents Database, 2·0 for USDA Survey Foods’(35), e.g. 1 cup of yoghurt equates to 245 g. Mean weights of the exemplary foods(28–33) of each food group were then assumed as the food-group-specific weight of one serving. These weights were multiplied with the recommended sex- and age-group-specific number of servings for each food group within the FGP. For the current analysis we used the FGP recommendations for boys and girls in the predefined age groups 9–13 years and 14–18 years of the FGP.

Anthropometric measurements

Measurements were performed by trained staff in a standardized way(Reference Nagy, Vicente-Rodriguez and Manios36) with the adolescents barefoot and in underwear. Weight was measured with an electronic scale to the nearest 0·1 kg, and height was measured with a telescopic stadiometer to the nearest 0·1 cm. BMI was calculated from height and weight (kg/m2). Sex- and age-independent BMI standard deviation scores (BMI-SDS) were calculated using Z-values for BMI, calculated via the LMS method by Cole et al.(Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal37) and overweight was defined according to age- and sex-standardized BMI cut-off points based on data of Cole et al.(Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal37) Skinfold thicknesses were measured three times on the left side of the body with a Holtain calliper to the nearest 0·2 mm. Body fat percentage was calculated from triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses using Slaughter's equations(Reference Slaughter, Lohman and Boileau38).

Socio-economic characteristics

Socio-economic characteristics were assessed with a self-reported questionnaire(Reference Iliescu, Beghin and Maes39). The adolescents reported whether their parents were overweight (yes/no) and their parents’ educational level (lower education/lower secondary or higher secondary/higher education/university degree). The familial affluence scale, which was previously validated(Reference Currie, Molcho and Boyce40), was used as an indicator of the adolescents’ material affluence. It was based on information about family car ownership, having one's own bedroom, Internet availability and computer ownership. Furthermore, migration status (born outside the country they lived in during the study: yes/no) and smoking status (ever smoked: yes/no) were assessed.

Health-related characteristics

Physical activity was assessed with the self-administered Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents covering questions about physical activity during the last 7 d(Reference Hagstromer, Bergman and De Bourdeaudhuij41). Total minutes per week (min/week) were computed and assigned to moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

To assess the nutritional knowledge of the adolescents, the validated Nutritional Knowledge Test was used(Reference Kersting, Sichert-Hellert and Vereecken42). For evaluation, correct answers to the twenty-three multiple-choice questions were summed up and used as a percentage of the total number of questions.

Diet-related preferences and determinants of healthy eating were examined using the Food Choices and Preferences Questionnaire and the Determinants of Healthy Eating Questionnaire(Reference Moreno, De Henauw and Gonzalez-Gross21). For this analysis we used questions about frequencies of breakfast skipping, bringing fruit to school and fruit availability at home.

Statistical analyses

SAS procedures (SAS statistical software package version 9·13; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) were used for data analysis. A P value < 0·01 was considered statistically significant. Sample weights were applied to adjust for exclusion of study participants due to insufficient data. The sampling weight calibrates the sample in such a way that it matches the European population with regard to sex and age group.

Differences in characteristics between boys and girls were tested using ANOVA for normally distributed variables, the Kruskal–Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables, or the χ 2 test for categorical variables.

Weighted intakes of food groups by the adolescents were calculated as medians (25th and 75th percentiles). Wilcoxon's rank-sum tests, applicable for non-normally distributions and paired observations, were used to test if the median of the individual differences between dietary intake and recommendations of each individual was zero(Reference Kirkwood and Sterne43).

Results

The present data analysis included 732 (46 %) boys and 861 (54 %) girls. Characteristics regarding anthropometry, socio-economic status and health are presented in Table 2 stratified by sex. In comparison with boys, girls had a lower BMI-SDS (0·2 v. 0·4) but a higher percentage of body fat (24·6 % v. 16·3 %), which was to be expected. Gender differences regarding socio-economic characteristics could only be observed for the percentage of overweight mothers (about 13 % in girls and 8 % in boys). With respect to health-related characteristics, boys reported significantly more physical activity than girls (about 640 min/week v. 430 min/week) and less frequent breakfast skipping (about 11 % v. 16 %), whereas girls reported a higher availability of fruit at home (about 47 % v. 41 %) and at school (about 14 % v. 6 %).

Table 2 CharacteristicsFootnote * of the study sample: 1593 European adolescents from the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescents) Study stratified by sex

* Values are presented as weighted frequencies, means (sd) or medians (25th and 75th percentiles).

† Significant differences between groups tested using ANOVA for normally distributed variables, Kruskal–Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables, or the χ 2 test for categorical variables.

‡ Derived from the sex- and age-specific cut-offs proposed by the International Obesity Task Force, which correspond to an adult BMI cut-off of 25 kg/m2(Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal37).

§ Estimated according to the equations of Slaughter et al.(Reference Slaughter, Lohman and Boileau38).

∥ Obtained from questions about adolescents’ perception.

¶ Higher secondary education and higher education or university degree.

** Based on information about family car ownership, having one's own bedroom, Internet availability and computer ownership.

†† Participant is born outside the country they lived in during the study.

‡‡ Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

§§ Percentage of questions answered correctly in the Nutritional Knowledge Test.

∥∥ Strongly agree with this statement from the Food Choices and Preferences Questionnaire.

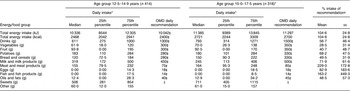

The weighted dietary intakes of food groups consumed by the European adolescents, stratified by sex and age group, and compared with the OMD, are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Boys and girls of both age groups significantly exceeded the OMD recommendations for energy intake (105 %, P < 0·01), except for the 15·0–17·5-year-old boys.

Table 3 Dietary intakes of food groups compared with the Optimized Mixed Diet (OMD), stratified by age group, among 732 European boys aged 12·5–17·5 years from the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescents) Study

*Values are presented as medians (25th and 75th percentiles).

†Values are presented as mean (sd) of the respective percentages of each individual's intake compared with the recommendation.

‡Wilcoxon rank-sum test shows that the median of differences between dietary intake and recommendations of each individual is significantly different from zero (P < 0·01).

§Maximum 1004 kJ/d (240 kcal/d) for age group 12·5–14·9 years; maximum 1130 kJ/d (270 kcal/d) for age group 15·0–17·5 years.

Table 4 Dietary intakes of food groups compared with the Optimized Mixed Diet (OMD), stratified by age group, among 861 European girls, aged 12·5–17·5 years from the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescents) Study

*Values are presented as medians (25th and 75th percentiles).

†Values are presented as mean (sd) of the respective percentages of each individual's intake compared with to the recommendation.

‡Wilcoxon rank-sum test shows that the median of differences between dietary intake and recommendations of each individual is significantly different from zero (P < 0·01).

§Maximum 816 kJ/d (195 kcal/d) for age group 12·5–14·9 years; maximum 921 kJ/d (220 kcal/d) for age group 15·0–17·5 years.

For both age groups of adolescent boys and girls, the average daily intakes and the OMD recommendations were significantly different for all food groups. For drinks, the HELENA boys and girls fulfilled the recommendations by about 60 %. Boys of the two age groups reached the recommendations for vegetables and fruit by only about 30 % and 40 %, respectively, whereas girls had slightly higher values (about 35 % and 50 %, respectively). OMD recommendations for potatoes as well as bread and cereals were reached by about 70 % and 50 %, respectively, for both genders. OMD recommendations for milk and milk products as well as for eggs were achieved to higher degrees by boys (70 % for milk products and 80 % for eggs) compared with girls (60 % of the recommendations for both food groups). For the meat and fish food groups, the European adolescents – especially the boys – exceeded the OMD recommendations. Boys had an average meat intake of about 230 % of the recommendations, girls of about 190 %. The average fish intake was about 160 % of the recommendations for boys and 150 % for girls. The OMD recommendation on oils and fats was fulfilled up to 40 % (girls) to 50 % (boys). Finally, the average intake of sweets (including sweetened beverages) was between 400 g and 700 g. The OMD tolerates a sweet intake of 10 % of the recommended energy intake, i.e. 837–1130 kJ/d (200–270 kcal/d). For comparison, 837–1130 kJ/d would be about 40–50 g of chocolate or potato crisps, about 60–80 g of wine gums or 450–650 ml of soft drinks. Therefore, the adolescents highly exceeded the OMD recommendations.

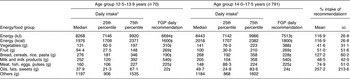

Similar results were found when comparing weighted dietary intakes of food groups of the HELENA participants with the FGP, as shown in Tables 5 and 6, stratified by sex and age group. As for the OMD, the adolescents’ average energy intake significantly exceeded the FGP recommendation for energy (about 120 %) in both boys and girls (P < 0·01). Furthermore, all food groups (except the meat, fish, eggs and pulses group for 13-year-old boys) showed significant differences between average daily intakes and recommendations.

Table 5 Dietary intakes of food groups compared with the Food Guide Pyramid (FGP), stratified by age group, among 732 European boys, aged 12·5–17·5 years from the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescents) Study

*Values are presented as medians (25th and 75th percentiles).

†Values are presented as mean (sd) of the respective percentages of each individual's intake compared with the recommendation.

‡Wilcoxon rank-sum test shows that the median of differences between dietary intake and recommendations of each individual is significantly different from zero (P < 0·01).

Table 6 Dietary intakes of food groups compared with the Food Guide Pyramid (FGP), stratified by age group, among 861 European girls, aged 12·5–17·5 years from the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescents) Study

*Values are presented as medians (25th and 75th percentiles).

†Values are presented as mean (sd) of the respective percentages of each individual's intake compared with the recommendation.

‡Wilcoxon rank-sum test shows that the median of differences between dietary intake and recommendations of each individual is significantly different from zero (P < 0·01).

Similar to the case of evaluating by use of the OMD, the fruit and vegetable intakes of the European boys were on average about 35 % of the FGP recommendations, while girls reached slightly higher values of about 40 % for vegetables and about 50 % for fruit recommendations. The intakes of bread, cereals, rice and pasta equalled on average about 130 % of the FGP recommendations for both genders. In the group of milk and milk products, boys fulfilled the FGP recommendations by 65 % and girls by about 50 %. In the group of meat, fish, eggs and pulses, boys also reached the recommendations to a higher degree of about 90 % compared with girls with about 75 %. The highest exceeding of the recommendations occurred in the oils, fats and sweets group, with more than 250 % in both genders.

Discussion

The present analysis provides for the first time evidence from a comprehensive and standardized dietary assessment that food intake in adolescents on a European level is not optimal in the light of European and US food-based dietary concepts. In particular, adolescents eat less than half of the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables and less than two-thirds of the recommended amount of milk (and milk products), but consume much more meat (and meat products) and oils, fats and sweets than recommended. Median total energy intake may be estimated to be nearly in line with the recommendations, although statistically significant differences emerge.

Although both food-based dietary guidelines are based on low physical activity levels(19, 44), the recommended energy intake in the OMD is about 1255–2510 kJ/d (300–600 kcal) higher than in the FGP. Therefore, the recommended intakes of the food groups potatoes (with rice and pasta), bread and cereals, as well as oils and fats, in the OMD is more than twice as high (about 450–650 g and 35–45 g, respectively) as in the FGP (about 200–300 g and 20–30 g, respectively), which explains the different achievement levels for the OMD and FGP in this study sample.

Unsatisfactory consumption of fruit, fruit juice and vegetables as well as milk and other dairy products has been reported for adolescents living in Central and Eastern Europe(Reference Parizkova45) and in Northern Europe(Reference Samuelson46). However, in Southern European countries intake of fruit and vegetables is higher than in Nordic regions(Reference Cruz47). A remarkable low fruit and even lower vegetable intake has been shown in the Pro Children Project, a cross-European survey focusing on fruit and vegetable intake in 11-year-old children in nine European countries(Reference Yngve, Wolf and Poortvliet48), similar to the youngest age groups of HELENA. A large proportion of the participants of the Pro Children Project stated a frequency of fruit and vegetable intake which was less than once per day. Similarly, a quarter of our HELENA adolescents did not consume any fruit during the two recalled days. Also a meta-analysis of Pomerlau et al.(Reference Pomerleau, Lock and Knai49) in fourteen sub-regions showed that the mean intake in adolescents across Europe was well below European public health recommendations for this food group, which are set to 400 g/d(Reference Byrne50).

On the other hand, adolescents consumed about 200 % of the OMD meat and meat products recommendation and also the consumption of sweets was far too high. Meat and meat products were previously also reported to be consumed frequently in Central, Eastern(Reference Parizkova45) and Northern Europe(Reference Samuelson46). Furthermore, snacking – for which food items like sweets and savoury snacks are most popular(Reference Samuelson46, Reference Cruz47) – is reported to be common in Northern Europe(Reference Samuelson46). In Western Europe, sucrose and fat intakes are high, and most amounts of protein are from animal sources, whereas fibre intake is low(Reference Rolland-Cachera, Bellisle and Deheeger51), pointing to similar food consumption patterns as those found in the HELENA sample.

Bread and bread products were consumed in large quantities in Central, Eastern(Reference Parizkova45) and Northern Europe(Reference Samuelson46), whereas an opposite picture for this food group resulted in HELENA from comparison with the two recommendations due to different definitions of food groups. For instance, the FGP includes cakes, pies, biscuits and savoury snacks in the bread and cereals group, whereas they are characterized as sweets in the OMD. Since snacks may have an adverse effect on body weight(Reference Janssen, Katzmarzyk and Boyce52), the conclusion that bread and cereal consumption is regarded as sufficient according to the FGP may be questionable. The same applies for meat, fish, eggs and pulses, which are considered as one group in the FGP and as separate groups in the OMD. A distinction between these food groups might be of importance, since consumption of fish and pulses has been found to benefit health(Reference Yashodhara, Umakanth and Pappachan53, Reference Venn and Mann54), contrary to meat(Reference Micha, Wallace and Mozaffarian55). Another important difference is that drinks are included in the OMD concept, but not in the FGP. Alcoholic beverages in particular are allocated as tolerated foods like sweets in the OMD, since they are characterized by low nutrient density, but high hedonic rating among adolescents. Regarding the FGP, beverages are not a single food group and thus all beverages are allocated as ‘others’. However, although alcohol consumption is common among European adolescents(Reference Samuelson46, Reference Cruz47), only about 6 % of the HELENA adolescents reported to have consumed alcoholic beverages during the two recall days and thus alcohol intake seems to be of minor importance in this sample. Hence, food intake quality can be estimated considerably different depending on what recommendations are used. In this analysis, it appears that the OMD – and to a greater extend the FGP – might overestimate the real dietary quality of adolescents with regard to special food groups, in particular the diverse group of sweets and snack foods. Furthermore, the oils and fats group in both the OMD and FGP did not include hidden fat from convenience foods, sauces or milk products. Therefore, oil and fat consumption may have been underestimated in the dietary survey.

In contrast, fruit intake may be slightly underestimated in the present analysis since fruit juice has not been included in the fruit group, as it has been shown that children and adolescents have problems distinguishing fruit juice from sweetened fruit drinks or lemonades(Reference Wind, Bobelijn and De Bourdeaudhuij56). In the OMD(Reference Kersting, Alexy and Clausen18) and FGP recommendations(19) one glass of 100 % fruit juice (200 ml) can be counted as one portion of fruit. Median intake of fruit and vegetable juice was 100 ml/d in girls and boys of both age groups (data not shown). Therefore, if fruit and vegetable juice would be added to the fruit group (assuming that children and adolescents are commonly drinking fruit but not vegetable juice(Reference Wind, Bobelijn and De Bourdeaudhuij56)), boys would on average fulfil the OMD and FGP fruit recommendations and girls would even exceed them. Therefore, our results may potentially be rather pessimistic with regard to fruit intake. However, it is not clear whether the reported half glass of juice is really 100 % juice and, moreover, a quarter of the sample did not report any juice consumption during the two recalled days at all (data not shown).

There are some gender differences regarding the compliance with the dietary recommendations that were to be expected. Whereas girls fulfilled more of the recommendations concerning fruit and vegetables, boys in their turn were better for milk and milk products as well as meat and meat products (i.e. more overconsumption when the OMD recommendations are considered). This gender difference is in line with the already often described observation that girls have an overall healthier choice of foods than boys(Reference Huybrechts, Matthys and Vereecken14, Reference Samuelson46, Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp57).

Furthermore, it has been shown that girls are more likely to under-report their dietary intake than boys(Reference Novotny, Rumpler and Riddick58), which is also a considerable problem in HELENA. Self-reported dietary intake tends to be particularly problematic in adolescents(Reference Brady, Lindquist and Herd59) and the 24 h recall used in HELENA was identified to have substantial under-reporting bias(Reference Vereecken, Covents and Matthys23, Reference Vereecken, Dohogne and Covents60). Therefore, under- and over-reporters were excluded for analysis. The excluded adolescents differed significantly from those eligible for analysis regarding their anthropometric and most socio-economic characteristics, but only for few health-related characteristics (data not shown) and thus could be assumed to have similar health consciousness. However, the included adolescents might have been more willing to participate in a dietary study. In a further analysis we examined the difference between the included and excluded adolescents regarding the fulfilment of the OMD and FGP recommendations, and observed that the groups indeed differed significantly in their adherence to the dietary concepts in nearly all food groups (except for drinks, fruits, eggs and fish for OMD and fruits for FGP; data not shown). This result points to the fact that data of the excluded adolescents were seriously biased. Therefore, it can be assumed that the data obtained in the present analysis from the included participants are reliable and allow meaningful information about food intake in European adolescents. Future evaluation of the HELENA dietary data should examine the reporting bias in more detail.

Since it is important to improve dietary habits early in life, the consumption of fruit and vegetables, the most neglected food group among adolescents in this and other surveys, should be promoted in children and adolescents in line with the strive for reducing the burden of diet-related diseases in later life. Evidence confirms that multi-component, multi-media approaches at the school setting, including behavioural and situational prevention, have been more successful(Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp57, Reference Blanchette and Brug61) than educational campaigns(Reference Pomerleau, Lock and Knai49). In line with this, the HELENA project comprises a computer-tailored intervention, which provides adolescents with individualized feedback about their dietary behaviour(Reference Moreno, Gonzalez-Gross and Kersting20, Reference Maes, Vereecken and Gedrich62, Reference Maes, Cook and Ottovaere63). Moreover, in the HELENA Study, information of adolescents’ food preferences will be used to guide the development of healthy new food products by the food industry(Reference De Henauw, Gottrand and De Bordeaudhuij4).

Some limitations of the present study need to be mentioned. To begin with, the HELENA-CSS cohort is not a fully representative European sample, but due to the selection procedure of classes from all schools in the cities representativeness can be at least achieved on the city level. This procedure is anticipated to give a fair approximation of the average picture of the situation, if the objective is only to describe the adolescents’ characteristics, as was the case in our study(Reference Moreno, De Henauw and Gonzalez-Gross21). Furthermore, the 24 h recall used in HELENA has been shown to be prone to under-reporting in a validation study(Reference Vereecken, Covents and Matthys23, Reference Vereecken, Dohogne and Covents60). However, owing to the exclusion of over- and under-reporters in our sample, systematic bias should have been reduced. Large within-person variation might be of concern, given that dietary data were assessed by only two 24 h recalls (and not on Fridays and Saturdays and holidays, since the 24 h recalls were all completed during school days). On the other hand, the still large sample size (nearly 1600 adolescents) should have alleviated large within-person variations(Reference van't Veer64). Additionally, the sample weights that were constructed after over- and under-reporters were excluded calibrated the sample in such a way that it matched the European population with regard to sex and age group.

One of the major strengths of the present study, besides the large sample size, is the geographical spread over ten European cities. Another strength is the use of the multiple source method, taking into account both between- and within-individual variability of the dietary intake data. Nevertheless, wide distributions of the achievement of the guidelines occurred, as can be seen in the standard deviations. Moreover, the present study is one of the first examining the total daily food consumption and not only the consumption of specific food groups among well-characterized adolescents across Europe with highly standardized and validated procedures. We used for the first time two existing food-based dietary concepts fulfilling public health approaches to translate nutrient-based recommendations into practical food-based recommendations. Such concepts are useful to evaluate food intake particularly in adolescents, especially since they were adapted for adolescents’ energy requirements. Since both concepts revealed broadly the same main conclusions, it can be proposed that food consumption has been truly evaluated in this large sample of European adolescents. Nevertheless, the HELENA food and nutrient intake data, together with biomarkers of nutritional status, may allow development of tailored food-based dietary guidelines for European adolescents that are still missing. In this endeavour it may be a specific challenge to consider particular national or regional food habits, e.g. pasta, potatoes, type of bread.

To conclude, the present study provides new, reliable evidence about food consumption patterns of European adolescents. In the light of actual food-based dietary concepts from Europe and the USA, European adolescents consume far too little fruit, vegetables and milk products, but far too much meat, meat products and sweets. A key message from this analysis might be that adolescents do not need to eat more or less (regarding energy), but need to rearrange their food patterns. The results do urge the need to improve the dietary habits of adolescents in order to maintain health in later life.

Acknowledgements

The HELENA Study took place with the financial support of the European Community Sixth RTD Framework Programme (Contract FOOD-CT: 2005-007034). The contents of this paper reflect the views of the authors and the rest of the HELENA Study Group members only; the writing group takes sole responsibility for the content of the paper and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. T.D.V. was financially supported by the Research Foundation, Flanders (Grant no. 1174609N 01). None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose. L.A.M. coordinated the project. L.A.M., M.G.-G. and M.K. designed and carried out the HELENA project. N.J. carried out preliminary data analysis. K.D. performed further data analyses and drafted the manuscript. M.K. provided critical input on the data analyses and on earlier versions of the manuscript and supervised the study. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data of the submitted manuscript. The participation of all adolescents in the HELENA Study is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendix

The HELENA Study Group

Coordinator: Luis A. Moreno.

Core Group members: Luis A. Moreno, Frédéric Gottrand, Stefaan De Henauw, Marcela González-Gross, Chantal Gilbert.

Steering Committee: Anthony Kafatos (President), Luis A. Moreno, Christian Libersa, Stefaan De Henauw, Jackie Sánchez, Fréderic Gottrand, Mathilde Kersting, Michael Sjöstrom, Dénes Molnár, Marcela González-Gross, Jean Dallongeville, Chantal C. Gilbert, Gunnar Hall, Lea Maes, Luca Scalfi.

Project Manager: Pilar Meléndez.

Universidad de Zaragoza (Spain): Luis A. Moreno, Jesús Fleta, José A. Casajús, Gerardo Rodríguez, Concepción Tomás, María I. Mesana, Germán Vicente-Rodríguez, Adoración Villarroya, Carlos M. Gil, Ignacio Ara, Juan Revenga, Carmen Lachen, Juan Fernández Alvira, Gloria Bueno, Aurora Lázaro, Olga Bueno, Juan F. León, Jesús Mª Garagorri, Manuel Bueno, Juan Pablo Rey López, Iris Iglesia, Paula Velasco, Silvia Bel.

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Spain): Ascensión Marcos, Julia Wärnberg, Esther Nova, Sonia Gómez, Esperanza Ligia Díaz, Javier Romeo, Ana Veses, Mari Angeles Puertollano, Belén Zapatera, Tamara Pozo.

Université de Lille 2 (France): Laurent Beghin, Christian Libersa, Frédéric Gottrand, Catalina Iliescu, Juliana Von Berlepsch.

Research Institute of Child Nutrition Dortmund, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn (Germany): Mathilde Kersting, Wolfgang Sichert-Hellert, Katharina Diethelm.

Pécsi Tudományegyetem (University of Pécs) (Hungary): Dénes Molnar, Eva Erhardt, Katalin Csernus, Katalin Török, Szilvia Bokor, Angster, Enikö Nagy, Orsolya Kovács, Judit Repásy.

University of Crete School of Medicine (Greece): Anthony Kafatos, Caroline Codrington, María Plada, Angeliki Papadaki, Katerina Sarri, Anna Viskadourou, Christos Hatzis, Michael Kiriakakis, George Tsibinos, Constantine Vardavas, Manolis Sbokos, Eva Protoyeraki, Maria Fasoulaki.

Institut für Ernährungs- und Lebensmittelwissenschaften – Ernährungphysiologie. Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms Universität (Germany): Peter Stehle, Klaus Pietrzik, Marcela González-Gross, Christina Breidenassel, Andre Spinneker, Jasmin Al-Tahan, Miriam Segoviano, Anke Berchtold, Christine Bierschbach, Erika Blatzheim, Adelheid Schuch, Petra Pickert.

University of Granada (Spain): Manuel J. Castillo, Ángel Gutiérrez, Francisco B. Ortega, Jonatan R Ruiz, Enrique G. Artero, Vanesa España-Romero, David Jiménez-Pavón, Palma Chillón, Magdalena Cuenca-Garcia.

Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca per gli Alimenti e la Nutrizione (Italy): Davide Arcella, Elena Azzini, Noemi Bevilacqua, Pasquale Buonocore, Giovina Catasta, Laura Censi, Donatella Ciarapica, Paola D'Acapito, Marika Ferrari, Myriam Galfo, Cinzia Le Donne, Catherine Leclerq, Giuseppe Maiani, Beatrice Mauro, Lorenza Mistura, Antonella Pasquali, Raffaela Piccinelli, Angela Polito, Raffaela Spada, Stefania Sette, Elisabetta Toti, Maria Zaccaria.

University of Napoli ‘Federico II’ Department of Food Science (Italy): Luca Scalfi, Paola Vitaglione, Concetta Montagnese.

Ghent University (Belgium): Ilse De Bourdeaudhuij, Stefaan De Henauw, Tineke De Vriendt, Lea Maes, Christophe Matthys, Carine Vereecken, Mieke de Maeyer, Charlene Ottevaere.

Medical University of Vienna (Austria): Kurt Widhalm, Katharina Phillipp, Sabine Dietrich, Birgit Kubelka, Marion Boriss-Riedl.

Harokopio University (Greece): Yannis Manios, Eva Grammatikaki, Zoi Bouloubasi, Tina Louisa Cook, Sofia Eleutheriou, Orsalia Consta, George Moschonis, Ioanna Katsaroli, George Kraniou, Stalo Papoutsou, Despoina Keke, Ioanna Petraki, Elena Bellou, Sofia Tanagra, Kostalenia Kallianoti, Dionysia Argyropoulou, Katerina Kondaki, Stamatoula Tsikrika, Christos Karaiskos.

Institut Pasteur de Lille (France): Jean Dallongeville, Aline Meirhaeghe.

Karolinska Institutet (Sweden): Michael Sjöstrom, Patrick Bergman, María Hagströmer, Lena Hallström, Mårten Hallberg, Eric Poortvliet, Julia Wärnberg, Nico Rizzo, Linda Beckman, Anita Hurtig Wennlöf, Emma Patterson, Lydia Kwak, Lars Cernerud, Per Tillgren, Stefaan Sörensen.

Asociación de Investigación de la Industria Agroalimentaria (Spain): Jackie Sánchez-Molero, Elena Picó, Maite Navarro, Blanca Viadel, José Enrique Carreres, Gema Merino, Rosa Sanjuán, María Lorente, María José Sánchez, Sara Castelló.

Campden BRI (UK): Chantal Gilbert, Sarah Thomas, Elaine Allchurch, Peter Burgess.

SIK – Institutet foer Livsmedel och Bioteknik (Sweden): Gunnar Hall, Annika Astrom, Anna Sverkén, Agneta Broberg.

Meurice Recherche & Development asbl (Belgium): Annick Masson, Claire Lehoux, Pascal Brabant, Philippe Pate, Laurence Fontaine.

Campden BRI Magyarország (Hungary): Andras Sebok, Tunde Kuti, Adrienn Hegyi.

Productos Aditivos SA (Spain): Cristina Maldonado, Ana Llorente.

Cárnicas Serrano SL (Spain): Emilio García.

Cederroth International AB (Sweden): Holger von Fircks, Marianne Lilja Hallberg, Maria Messerer

Lantmännen Food R&D (Sweden): Mats Larsson, Helena Fredriksson, Viola Adamsson, Ingmar Börjesson.

European Food Information Council (Belgium): Laura Fernández, Laura Smillie, Josephine Wills.

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (Spain): Marcela González-Gross, Jara Valtueña, Ulrike Albers, Raquel Pedrero, Agustín Meléndez, Pedro J. Benito, Juan José Gómez Lorente, David Cañada, David Jiménez-Pavón, Alejandro Urzanqui, Francisco Fuentes, Rosa María Torres, Paloma Navarro.