Introduction

Obesity has nearly doubled worldwide since 1980( 1 ) and this has implications for maternal health. In the UK, the prevalence of first-trimester obesity more than doubled between 1989 and 2007 from 7·6 % to 15·6 %( Reference Heslehurst, Rankin and Wilkinson 2 ). Being overweight or obese at the start of pregnancy is associated with adverse health outcomes for the mother and baby( Reference Marchi, Berg and Dencker 3 – Reference Walter, Perng and Kleinman 14 ), including increased risk of gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, Caesarean section, miscarriage, preterm delivery, stillbirth, postpartum haemorrhage and infections and postpartum depression( Reference Marchi, Berg and Dencker 3 – Reference Kirkegaard, Stovring and Rasmussen 7 , Reference Poston, Caleyachetyy and Cnattingius 12 ). For the baby, maternal obesity is associated with increased risk of inter-uterine growth restriction, neural tube defects, congenital anomalies, large for gestational age, reduced likelihood and shorter period of exclusive breast-feeding, as well as increased risk of offspring adiposity and infant death( Reference Marchi, Berg and Dencker 3 – Reference Scott‐Pillai, Spence and Cardwell 5 , Reference Fraser, Tilling and Macdonald-Wallis 8 – Reference Knight-Agarwal, Williams and Davis 11 , Reference Godfrey, Reynolds and Prescott 13 ), and may have implications for the long-term health of the offspring in relation to risk of chronic disease. Furthermore, gaining too much weight during pregnancy (i.e. excessive gestational weight gain (GWG)) and postpartum weight retention (PPWR; calculated as weight after delivery minus pre-pregnancy weight( Reference Rasmussen and Yaktine 15 )) are established predictors of long-term obesity( Reference Marchi, Berg and Dencker 3 , 4 , Reference Leslie, Gibson and Hankey 6 , Reference Kirkegaard, Stovring and Rasmussen 7 , Reference Walter, Perng and Kleinman 14 ). Women are at an increased risk for weight gain during the reproductive years and the childbearing years can set some women on an upwards weight trajectory for the decades ahead. Having one child doubles the 5- and 10-year obesity incidence for women and many women who gain excessive weight during pregnancy remain obese permanently( Reference Spencer, Rollo and Hauck 16 ). Systematic review evidence( Reference Nascimento, Pudwell and Surita 17 – Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 ) and NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) Public Health Guidance( 4 ) both highlight that there are currently gaps in knowledge about effective and appropriate weight-management interventions in women during the postpartum period.

Effective strategies to support optimisation of weight before pregnancy, appropriate GWG and appropriate postpartum weight loss are, therefore, needed to help women regulate their weight during the childbearing years and beyond. The postpartum period is an opportune time to intervene to shape new health behaviours for several reasons. It is a stage in life when women may have heightened awareness about health in general and so may be receptive to information about lifestyle, thus representing a teachable moment in the lifecourse( Reference Phelan 20 ). It is also a time when many women will be starting to prepare for the next pregnancy (i.e. it is the pre-conception period for the next pregnancy) and so there is the potential to set women on a positive course for subsequent pregnancies. Furthermore, transitions in maternal health attitudes and behaviours have the potential to benefit the wider family as women have a major influence on household eating behaviours. On the other hand, the postpartum period is also a challenging time to intervene owing to the major physiological, psychological and social changes taking place in the lives of new mothers and this must be carefully considered when developing interventions for this group.

The present review will examine the trajectory of postpartum weight change, the health risks associated with PPWR or gaining weight between pregnancies, the predictors of PPWR, barriers to weight management during the postpartum period and what interventions currently tell us about how best to support weight management in postpartum women.

Trajectory of postpartum weight change

At birth, the weight of the baby, the amniotic fluid and placenta is lost, and by 6 weeks, blood volume has decreased to pre-pregnancy levels and the uterus has returned to its normal size. Excess weight remaining after this time is mainly body fat stores. Accordingly, there are large maternal weight losses in the first 6 weeks after birth, particularly in the first 2–3 weeks postpartum( Reference Gunderson, Abrams and Selvin 21 – Reference Schmitt, Nicholson and Schmitt 23 ). A prospective cohort study of 985 American women from different ethnic backgrounds (Asian, Hispanic, black and white), in the decade between 1980 and 1990, reported that about half of net gestational weight (net delivery weight minus pregravid weight at the first pregnancy) was lost by 6 weeks postpartum, with mean weight retention being 3–7 kg( Reference Gunderson, Abrams and Selvin 21 ). About one in three women reached their pre-pregnancy weight within 6 weeks after delivery and early net postpartum weight loss (6 weeks postpartum weight minus delivery weight) was similar for all BMI groups( Reference Phelan 20 ). In a more recent North Carolina cohort recruited between 2001 and 2005, about 20 % of women returned to their pre-pregnancy weight or less by 3 months postpartum( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 ).

Although many women will return to their pre-pregnancy weight within 1 year of delivery, estimates from a contemporary cohort of 413 women in America( Reference Lipsky, Strawderman and Olson 25 ) indicate that 24 % of the sample had major PPWR (>4·55 kg or 10 lb) at 1 year. This figure is similar to the findings from the North Carolina cohort described above (27 % of women retained at least 4·55 kg or more at 1 year postpartum)( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 ), but both these estimates are higher than that reported by Gunderson et al. ( Reference Gunderson, Abrams and Selvin 21 ) in 2001 where 15–20 % of women retained more than 4–5 kg (about 9–11 lb) at 1 year.

Retaining weight between pregnancies is an important contributor to obesity. Irrespective of pre-pregnancy BMI, it is estimated that one in five women move into a higher BMI category at 18 months postpartum( Reference Crosby, Collins and O’Higgins 26 ). The majority of women who have a normal BMI before their first pregnancy increase more than a half BMI unit at their second pregnancy( Reference Villamor and Cnattingius 27 ) and it has been estimated that about one in five (21·4 %) women with a normal pre-pregnancy BMI move into the overweight category post-pregnancy( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 , Reference Gunderson and Abrams 28 – Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ), and 7·6 % are classed as obese at 3 years( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ).

In women who are obese pre-pregnancy, 97 % will remain obese after 1 year( Reference McBain, Dekker and Clifton 31 ). Also, 40 % of obese women may gain two or more BMI units between the first and second pregnancies, and so may also move up to a higher obese class( Reference Jain, Gavard and Rice 32 ). Between 40 and 50 % of women who are overweight pre-pregnancy move into the obese category by 12 months postpartum( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 ). Gunderson et al. ( Reference Gunderson, Abrams and Selvin 21 ) examined late postpartum weight change between pregnancies in over 900 women (calculated as weight at the start of the second pregnancy minus weight at 6 weeks postpartum first pregnancy; median of 2 years) and found that weight loss varied according to pregravid BMI; the low and average BMI groups lost 4 kg more than the highest BMI group( Reference Gunderson, Abrams and Selvin 21 ). An increase in BMI between pregnancies is associated with significant health risks as described in the next section.

Most data on weight loss after pregnancy focus on weight loss in the first few months, with some examining weight change up to 18 months( Reference Lipsky, Strawderman and Olson 25 ) and much less attention being given to the postpartum period beyond 18 months which, for many women, will represent the pre-conceptual period for a subsequent pregnancy( Reference Lipsky, Strawderman and Olson 25 ). Understanding weight change over the entire inter-pregnancy period is critical to inform interventions that can help women stabilise their weight between pregnancies. Lipsky et al. ( Reference Lipsky, Strawderman and Olson 25 ) examined weight change between 1 and 2 years postpartum in a cohort of 413 women in New York. They found that about one in four women gained weight (more than 2·25 kg) during this late postpartum phase. Women who were overweight or obese at the 1-year postpartum time point were more likely to gain weight between 1 and 2 years than women with a normal pre-pregnancy BMI (OR 2·38 and 2·92, respectively). The Active Mothers Postpartum study( Reference Østbye, Peterson and Krause 33 ) of 450 overweight and obese women assessed weight at 6 weeks and 12, 18 and 24 months and also showed an upwards trajectory for weight between 12 and 24 months, particularly for women in obese class II and III. Reasons why some women seem to gain weight after about 12 months postpartum are unknown but are likely to be owing to environmental and lifestyle factors related to caring for one or more children postpartum. Studies that assess such factors alongside weight status from the early to late postpartum period will help to identify if there are specific modifiable factors that need to be targeted to achieve long-term weight stabilisation in postpartum women.

As well as helping us to understand women’s weight trajectories after pregnancy, this study( Reference Østbye, Peterson and Krause 33 ) highlights the importance of measuring weight at regular intervals through the entire postpartum period in order to differentiate between retention of GWG and weight gain that originates solely during the postpartum period( Reference Schmitt, Nicholson and Schmitt 23 , Reference Lipsky, Strawderman and Olson 25 ). This is an important distinction to make in epidemiological studies examining the relationship between PPWR and adverse health outcomes for mother and baby. Indeed, it has been suggested that the term PPWR be preserved for a short duration after parturition (for example, up to 12 to 18 months postpartum)( Reference Schmitt, Nicholson and Schmitt 23 ) and the term ‘postpartum weight difference’ may be more appropriate for studies examining the extended postpartum period; together these represent the ‘inter-pregnancy’ period for women who go on to have more children. Weight at the start of subsequent pregnancies is therefore a function of the woman’s BMI before her first pregnancy, the amount of weight gained during pregnancy, the amount of gestational weight that is lost postpartum and weight gain that originates during the postpartum period. Abebe et al. ( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ) found three groups of postpartum weight trajectories in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study of nearly 50 000 mothers where weight had been measured at 0·5, 1·5 and 3 years. Most women (86 %) had a low level of PPWR (0·5 kg) and a slight gain in weight over 3 years (<2 kg), 5·6 % had a high PPWR at 6 months (8 kg) followed by marked weight loss over the next 2·5 years (2·63 kg/year on average), and 8·5 % had high weight retention (5 kg) at 6 months and an increase in weight over the next 2·5 years (by 1·43 kg/year).

A longitudinal study using a series of interviews with thirty-six women from pregnancy through to the postpartum period( Reference Devine, Bove and Olson 34 ) observed that women broadly fell into four different trajectories characterised by their orientations towards their weight and diet and physical activity during pregnancy and into the postpartum period. These were named as ‘relaxed maintenance’, ‘exercise’, ‘determined’ and ‘unhurried’. The ‘relaxed maintenance’ trajectory discussed having their own strategies that enabled them to maintain their weight without having to focus on it too much. The ‘exercise’ trajectory was characterised by women who described exercise as a priority for them before, during and after pregnancy; they were similar to the ‘relaxed maintainers’ in their eating behaviours but different from the ‘relaxed maintainers’ in relation to prioritising ‘formal’ exercise. The ‘determined’ trajectory was comprised of women who perceived themselves to be overweight before pregnancy and were determined to lose their pregnancy weight and a bit more in the postpartum period. The ‘unhurried’ trajectory comprised women who were quite relaxed about their weight, diet and activity and had chosen not to prioritise weight loss during the postpartum year.

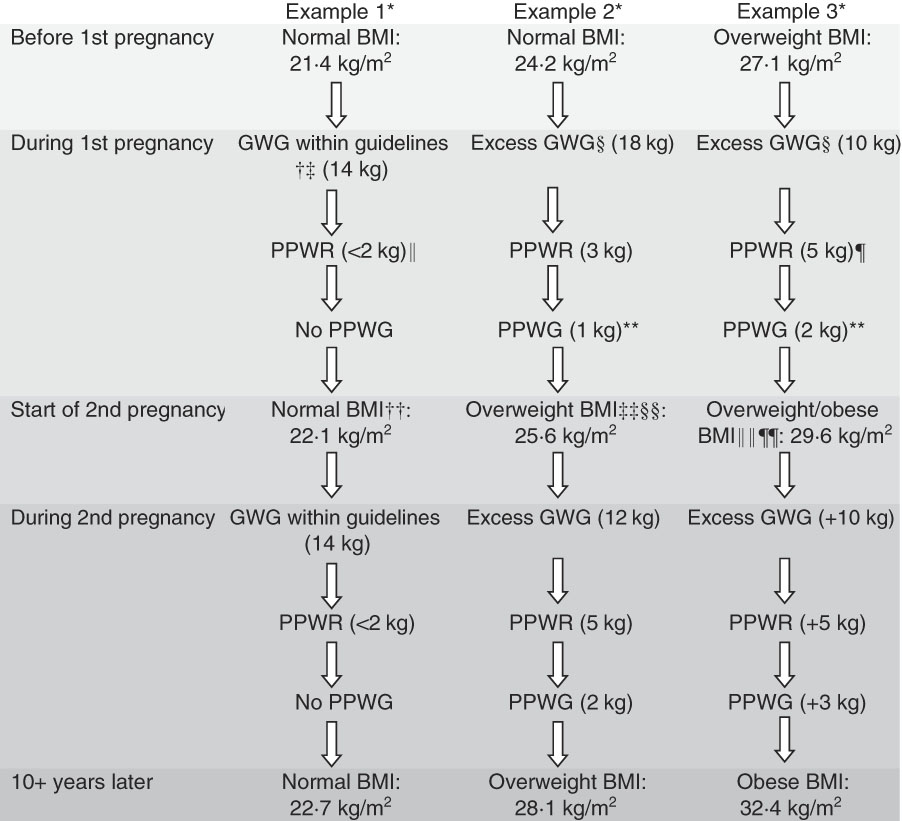

Fig. 1 shows an example of three weight stories or trajectories for women from the first to second pregnancies through to a decade later and illustrates how women can easily change BMI categories during this time through the accumulation of small weight gains at key stages; for example, gaining too much weight during pregnancy and/or not losing all weight gained during pregnancy and/or gaining weight during the late postpartum period (which is the pre-conception period for the next pregnancy).

Fig. 1 An example of three weight trajectories for women as they progress from the first pregnancy to second pregnancy then through to a decade later, illustrating the stages where women can easily gain weight, and so change BMI categories, during the childbearing years. * Height=1·68 m; example 1, weight=60·3 kg; example 2, weight=68·0 kg; example 3, weight=76·2 kg. † Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines( Reference Rasmussen and Yaktine 15 ). ‡ Norwegian mother and child cohort – 35·5 % women gained within IOM guidelines( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ). § Norwegian mother and child cohort – 40 % women gained in excess of IOM guidelines( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ). II North Carolina cohort – 20 % of women returned to their pre-pregnancy weight or less by 3 months postpartum( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 ). ¶ Two American cohorts – 24–27 % of women had major postpartum weight retention (PPWR) (>4·55 kg or 10 lb) at 1 year( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 , Reference Lipsky, Strawderman and Olson 25 ). ** New York cohort – one in four women gained weight (more than 2·25 kg) between 1 and 2 years postpartum( Reference Lipsky, Strawderman and Olson 25 ). †† On average, women with a normal BMI gained 1 kg/m2 between their first and second pregnancies( Reference Bogaerts, Van den Bergh and Ameye 37 ). ‡‡ 18 months after having first baby one in five women moved into a higher BMI category( Reference Crosby, Collins and O’Higgins 26 ). §§ 21·4 % of women with a normal pre-pregnancy BMI moved into the overweight range and 7·6 % moved into the obese range at 3 years( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ). IIII 40 % of obese women gain two or more BMI units between their first and second pregnancies( Reference Jain, Gavard and Rice 32 ). ¶¶ 40–50 % of overweight women pre-pregnancy moved into the obese category by 12 months postpartum( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 , Reference Endre, Straub and McKinney 107 ). GWG, gestational weight gain; PPWG, postpartum weight gain.

Overall, it is clear that there is significant variability in postpartum weight trajectories between women and it is likely that new mothers will be ready to engage with weight-management interventions at different stages after birth. The optimal time to engage women in postpartum weight management is still unknown( Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 ) and, given what we know about the chaotic nature of the postpartum period and the wide differences in women’s lived experience of the postpartum period, it is likely that flexibility is needed regarding postpartum interventions. Whilst some women may be ready to engage with weight management a few months after birth, others may not be ready to engage until much later. Interventions that have flexibility regarding time to opt in may be more likely to have optimal reach, but this is something that needs to be tested in trials that allow opt in over a wider postpartum period.

Health risks associated with postpartum weight retention or gaining weight between pregnancies

The health implications of weight gain between successive pregnancies, which can be owing to retaining gestational weight and/or weight gain that originates in the postpartum period, have been examined in several cohorts. A large Swedish cohort( Reference Villamor and Cnattingius 27 ) of more than 150 000 women who had their first two singleton births between 1992 and 2001 examined if change in BMI between the first and second pregnancies was associated with risk of adverse outcomes during the second pregnancy. Women who gained more than three BMI units between pregnancies (average 2 years), compared with those who gained less than one BMI unit between pregnancies, had an increased risk of pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), Caesarean delivery and stillbirth, and the relationship was linearly related to the amount of weight gained. Another study based on data from a similar time frame also found that an increase in inter-pregnancy BMI was associated with increased risk of GDM( Reference Ehrlich, Hedderson and Feng 36 ).

More contemporaneous cohorts provide estimates of risk to the infant and mother from inter-pregnancy weight gain according to first-pregnancy BMI. A study of nearly 8000 women who had two consecutive live, singleton births between 2009 and 2011 in Belgium( Reference Bogaerts, Van den Bergh and Ameye 37 ) found that inter-pregnancy weight change was associated with increased risk for perinatal complications, including an increased risk of Caesarean delivery (OR 2·04) in overweight or obese women who gained two or more BMI units between pregnancies. Inter-pregnancy weight change also influenced risk for those who were underweight or normal weight, with a weight gain of more than two to three BMI units between pregnancies in these women being associated with an increased risk of GDM (OR 2·25 for a gain of more than two BMI units) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (OR 3·76 for a gain of more than three BMI units). Furthermore, for underweight or normal-weight women, losing more than one BMI unit between pregnancies was associated with a halving in the risk for macrosomia in the infant but a doubling in the risk for low birth weight. The change in the BMI profile of the population from the first to second pregnancy was notable: in the first pregnancy, 18 % were overweight and 7 % were obese; in the second pregnancy, 22 % were overweight and 10 % were obese.

An Australian cohort of 5371 women who had first and second consecutive singleton live births between 2000 and 2012( Reference McBain, Dekker and Clifton 31 ) also examined risk according to pregravid BMI. Women who were normal weight in their first pregnancy and gained more than four BMI units by the start of the second pregnancy had an increased risk of GDM, macrosomia and having a large-for-gestational-age infant. As for the Belgium study above, a reduction in BMI of more than two units in normal-weight women was associated with increased risk of small for gestational age. The risks for overweight or obese women were slightly different, with an increase in BMI of more than two units being associated with an increased risk of GDM in the second pregnancy but having no association with risk of macrosomia, small for gestational age or large for gestational age in the infant. A reduction in BMI of more than two units in overweight or obese women between pregnancies was, however, associated with reduced risk of small for gestational age and GDM. Effects on placental weight have been proposed as a potential mediating factor in the relationship between BMI and risk of large for gestational age or small for gestational age; weight loss has been associated with increased risk of low placental weight, and weight gain with increased risk of placental oversize( Reference Wallace, Bhattacharya and Campbell 38 ).

Consistent with the findings above, a retrospective cohort study of an Australian obstetric population( Reference Knight-Agarwal, Williams and Davis 11 ) between 2008 and 2013 (n 14 875) reported that an inter-pregnancy increase in BMI of more than three BMI units in multiparous women was associated with a higher risk of low 5-min Apgar score (OR 3·2), GDM (OR 3·3) and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (OR 3·9). Wallace et al. ( Reference Wallace, Bhattacharya and Campbell 39 ) reported similar findings in relation to recurrent pregnancy complications in a retrospective cohort study of 24 000 women who had singleton births between 1986 and 2013 in Aberdeen city in Scotland and also noted that women with a healthy BMI at their first pregnancy were more sensitive to the potential risk or benefits associated with weight change during pregnancy.

These studies highlight the need to focus attention not just on women who are overweight or obese at the start of pregnancy but on all women, as shifts in BMI can easily occur between pregnancies even in women who are normal weight at the start of their first pregnancy.

Predictors of postpartum weight retention

Epidemiological studies have identified a number of predictive factors of PPWR, including biological, lifestyle, socio-economic and psychological factors, which may account for the wide variance in PPWR( Reference Gunderson and Abrams 28 ).

Excess gestational weight gain

GWG outside of Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations( Reference Rasmussen and Yaktine 15 ) has consistently been identified as a predictor of PPWR, both in the short and long term( Reference Gunderson and Abrams 28 , Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 , Reference Siega-Riz, Viswanathan and Moos 40 – Reference Martin, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks 46 ), and high pre-pregnancy BMI may increase the likelihood of PPWR( Reference Gunderson and Abrams 28 , Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 , Reference Martin, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks 46 , Reference Gore, Brown and West 47 ). A meta-analysis of nine observational studies of singleton pregnancies found women gaining above IOM recommendations retained, on average, an additional 3·06 kg 3 years after delivery, and 4·72 kg on average after>15 years compared with women who gained weight within recommendations( Reference Nehring, Schmoll and Beyerlein 41 ). Similarly, a meta-analysis investigating the association between GWG and PPWR and obesity in singleton pregnancies reported that gaining in excess of IOM guidelines, compared with within guidelines, is associated with retaining approximately 3 kg more up to 21 years postpartum( Reference Mannan, Doi and Mamun 42 ). Indeed, high pre-pregnancy BMI and excess GWG have been suggested as indicators of a general susceptibility to gaining weight( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ), and excessive GWG and PPWR in one pregnancy are risk factors for similar developments in subsequent pregnancies( Reference Linné and Rössner 29 ).

Most studies investigating excess GWG and PPWR focus on women with singleton pregnancies. The presence of multiple fetuses influences GWG; for example, mean GWG has been estimated as 10·0–16·7 kg in a singleton pregnancy in normal-weight adults v. 15·5–21·8 kg in a twin pregnancy( Reference Rasmussen and Yaktine 15 ). Only two studies, to our knowledge, have reported data on GWG and PPWR in twin pregnancies. These retrospective cohort studies of fifty-nine( Reference Petit, Schrimmer and Alblewi 48 ) and 118( Reference Hickman, Roland and Newman 49 ) twin pregnancies, respectively, found that more than 30 % of women exceeded GWG guidelines for a twin pregnancy and, as for singleton pregnancies, pre-pregnancy obesity( Reference Petit, Schrimmer and Alblewi 48 ) and excess GWG were associated with a higher risk of PPWR( Reference Hickman, Roland and Newman 49 ). Although this suggests that excess GWG may have similar influences on PPWR in singleton and multiple pregnancies, mothers of multiples are likely to face additional demands in the postpartum period as a result of caring for two or more babies and this may make weight management more challenging for mothers of multiples v. mothers of singletons.

A high level of PPWR is probably attributable to the extension of sub-optimal diet and activity patterns from pregnancy into the postpartum period where weight management in general becomes a major challenge. However, there may be biological factors at play, for example, the increased insulin resistance associated with excess gestational weight gain, particularly the excess adipose tissue that tends to result from excess GWG, may extend into the postpartum stage( Reference Hedderson, Gunderson and Ferrara 50 ).

Breast-feeding

Infant feeding method may also influence PPWR and breast-feeding is beneficial for maternal and infant health. Breast-feeding may influence PPWR due to the energy cost of producing milk; however, this could be offset by an increase in appetite experienced by the mother during lactation. Indeed, its effect on postpartum weight is still uncertain, with studies reporting mixed results ranging from a positive association with postpartum weight loss to no association with PPWR in women who breast-feed compared with those who do not( Reference Gunderson and Abrams 28 , Reference Neville, McKinley and Holmes 51 ). A systematic review of observational studies (thirty-seven prospective and eight retrospective studies) found that, overall, the majority (63 %; n 27) reported no association between breast-feeding and postpartum weight change. However, among the studies of highest methodological quality (n 5), four studies did report a positive association between breast-feeding and postpartum weight change( Reference Neville, McKinley and Holmes 51 ). Studies published since have not yet clarified this relationship( Reference Martin, Hure and Macdonald-Wicks 46 , Reference Kirkegaard, Nohr and Rasmussen 52 ). One of the challenges in trying to estimate the impact of breast-feeding on weight loss is quantifying details on the exclusivity and duration of breast-feeding; data on partial v. exclusive breast-feeding are not always collected in studies and the extent of breast-feeding can change very quickly during the postpartum period. This makes it difficult for women to report their breast-feeding patterns and, ideally, data collection at multiple time points is needed to enable accurate characterisation of infant feeding method. As well as the potential for misclassification of the exposure, observational studies examining the relationship between breast-feeding and postpartum weight change may not fully control for confounding by maternal characteristics( Reference Neville, McKinley and Holmes 51 ).

Racial–ethnic influences

Research suggests there may be racial–ethnic differences in PPWR. It is unclear whether this variation is owing to biological factors, or attributable to disproportionate exposure to social factors that affect health, or prevailing cultural factors that influence weight management in women. Data from a population-based cohort study in Norway modelled the relationship between ethnicity and weight retention at 14 weeks postpartum, finding women from minority groups had significantly higher PPWR than Western European women; those from the Middle East retained 2·0 kg, South Asia 2·8 kg and Africa 4·4 kg, more weight in comparison. A review from the USA of twelve studies( Reference Headen, Davis and Mujahid 53 ) examining racial–ethnic differences in GWG and PPWR found Asian, black American and Hispanic women were more likely to have GWG outside of the IOM’s guidelines compared with white women. Specifically, the prevalence of inadequate GWG was greater in Asian, Hispanic and black women, whereas the prevalence of excessive GWG was greater among white women; although more than 40 % of Hispanic and black women gained above the IOM upper recommended limit. Black women were more likely to retain considerable amounts of weight postpartum compared with both Hispanic and white mothers. Studies were inconclusive as to whether Hispanic women retained more or less weight postpartum. A few studies have examined the relationship between ethnicity and PPWR in European cohorts. The ABCD multi-ethnic cohort( Reference van Poppel, Hartman and Hosper 54 ) of 4213 women from the Netherlands found that Turkish women had significantly more weight retention than Dutch women. A population-based cohort study of 642 women in Norway( Reference Waage, Falk and Sommer 55 ) found women from minority groups had significantly higher PPWR than Western European women; those from the Middle East retained 2·0 kg, South Asia 2·8 kg and Africa 4·4 kg, more weight in comparison with Western women. Research in relation to ethnicity has been limited by the broad classification of racial–ethnic groups as ‘black’ or ‘Hispanic’ or ‘Latino’ which masks the different cultural backgrounds enveloped within such definitions; for example, ‘Hispanic’ or ‘Latino’ is used to categorise a range of different ethnicities, including Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban and Dominican( Reference Bogaerts, Van den Bergh and Ameye 37 ). Accounting for immigrant v. non-immigrant status within a country or region also tends to be overlooked but is essential to help enhance our understanding of the relative influence of biological, cultural and environmental factors in racial–ethnic differences in PPWR( Reference Headen, Davis and Mujahid 53 ).

Psychosocial factors

A number of psychosocial factors have been associated with PPWR. Pedersen et al. ( Reference Pedersen, Baker and Henriksen 56 ) found that PPWR was higher in women who were more likely to feel depressed, anxious or distressed in pregnancy and at 6 and 18 months postpartum. Those who were depressed or anxious during pregnancy and into the first 6 months postpartum were at highest risk for PPWR at 18 months( Reference Pedersen, Baker and Henriksen 56 ). Depressive symptoms at delivery, and depression and life stress during the first year postpartum, are also positively associated with greater PPWR( Reference Goldstein, Rogers and Ehrenthal 57 , Reference Whitaker, Young-Hyman and Vernon 58 ). Poor psychological health presents a unique set of challenges during the postpartum period, in addition to the challenges of caring for a new baby, and is likely to negatively affect the woman’s ability to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviours which reduce PPWR.

Low levels of sleep at 3 months postpartum were identified as a predictor of PPWR( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 ) in a North Carolina cohort of 688 women, and sleeping 5 h or less at 6 months postpartum was strongly associated with PPWR at 1 year( Reference Gundersen, Rifas-Shiman and Oken 59 ) in a Massachusetts cohort of 940 women. Furthermore, short sleep duration in the first year postpartum is associated with higher maternal adiposity at 3 years postpartum( Reference Taveras, Rifas-Shiman and Rich-Edwards 60 ). Low sleep duration may have an impact on the ability of mothers to undertake lifestyle behaviours such as physical activity and planning and preparing healthy meals. Alternatively, lack of sleep may operate on metabolic pathways influencing insulin resistance, energy expenditure and appetite( Reference Lucassen, Rother and Cizza 61 ).

Sociodemographic and lifestyle factors

Other sociodemographic and lifestyle factors predictive of PPWR have also been identified. A prospective cohort study of women in North Carolina reported that predictors of PPWR, at both 3 (n 688) and 12 months (n 550) postpartum, included young maternal age, unemployment, low educational attainment, having a baby who was hospitalised, disordered eating behaviours and high total energy intake( Reference Siega-Riz, Herring and Carrier 24 ). Exercise frequency, changes in dietary intake, single status, age under 20 years or over 40 years at delivery( Reference Olson, Strawderman and Hinton 43 ), parity( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 , Reference Maddah and Nikooyeh 44 ) and smoking cessation( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ) have also been significantly associated with PPWR. Lower income is also related to greater PPWR( Reference Pedersen, Baker and Henriksen 56 ), with the impact of GWG in excess of IOM guidelines reported to be three times greater in lower- than higher-income women( Reference Olson, Strawderman and Hinton 43 ). However, the recent work of Abebe et al. ( Reference Abebe, Von Soest and Von Holle 30 ) on the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study highlighted that PPWR or inter-pregnancy weight gain was still an important issue for women in their cohort who had a relatively high level of income and education.

Barriers to weight management in the postpartum period

Qualitative research provides important insights into the key barriers and facilitators of health-related behaviours in different populations at different life stages. The challenges that women face with postpartum weight loss have been captured in the work of Montgomery et al. ( Reference Montgomery, Bushee and Phillips 62 ) who conducted phenomenological interviews with twenty-six women aged 25–35 years about their experiences of weight management after pregnancy. The over-riding sentiment that was evident from these interviews was that women really struggled to balance the demands of the postpartum period with weight management, or indeed, taking care of themselves in general. The key challenges discussed by women were time and motivation issues, and the need for support. The women discussed the many different calls they had on their time including infant care responsibilities (which on their own can be overwhelming), alongside caring for other children, running a home and also working outside the home. Women also discussed how the routines they used to have had changed. They also felt their priorities had changed, meaning their own needs came last; hence personal care, including finding time to eat well and be active, were at the bottom of their list. They discussed the importance of support from partners, family, health professionals, friends and other mothers, commenting that this can either be a positive facilitator, or, on the other hand, can act to discourage them from taking time for themselves and making positive changes to their diet. The same challenges were also evident in the work of Devine et al. ( Reference Devine, Bove and Olson 34 ), who conducted a series of interviews with thirty-six women from pregnancy through to the postpartum period, which clearly described the increased complexity of life in general after having a baby.

Some work has focused specifically on physical activity; Evenson et al. ( Reference Evenson, Aytur and Borodulin 63 ) used a questionnaire to examine self-reported beliefs, barriers and enablers to being active in 530 women at 3 and 12 months postpartum. The most common barriers were lack of time, issues with child-care and tiredness. The most common enablers were partner support and the desire to feel better. More recently, Saligheh et al. ( Reference Saligheh, McNamara and Rooney 64 ) explored women’s perceptions of the postpartum period and their physical activity during this time using interviews (n 14) and identified similar barriers at the personal level but, in addition, a lack of motivation and confidence to engage in activity were also discussed in their interviews. Environmental barriers to physical activity were lack of access to affordable and appropriate activities and poor access to public transport. The qualitative work of Groth & David( Reference Groth and David 65 ), with forty-nine ethnically diverse women interviewed during the first year after childbirth, indicated that walking was perceived as a good form of postpartum exercise but also highlighted the need for social support to enable and encourage this activity. Neiterman & Fox( Reference Neiterman and Fox 66 ) reported a difference in the physical activity discourse according to social class amongst a sample of sixty-three Canadian women. They noted that working-class women appeared to invest less time and money in exercise strategies, avoiding activities that cost money for the activity itself or the transport to engage in the activity. This was in contrast to middle-class women who talked about going to the gym, hiring a personal trainer or attending a boot camp. For some women time to exercise is viewed as important ‘me’ time, whereas for other women time to exercise makes them feel conflicted about being away from the baby and so is not viewed in the same positive terms( Reference Devine, Bove and Olson 34 , Reference Saligheh, McNamara and Rooney 64 , Reference Neiterman and Fox 66 ).

Having a baby is a life-changing event for women. It is a period of major adjustment to the new demands of motherhood whilst still recovering from the physical demands of pregnancy and childbirth, alongside the general demands of running a home and coping with other family responsibilities. Women are concerned about pregnancy having a lasting or long-term effect on their body weight and do express a desire to gain control of their body and get back to feeling like themselves( Reference Devine, Bove and Olson 34 , Reference Neiterman and Fox 66 , Reference Fox and Neiterman 67 ). Many women feel pressure to conform to the feminine body ideals perpetuated by society which centre around removal of all signs of pregnancy as soon as possible after the birth of the baby( Reference Neiterman and Fox 66 , Reference Fox and Neiterman 67 ). Readiness and ability to take positive action will vary substantially between individuals owing to the myriad of factors related to self-care behaviours, some of which may be outside of their control, such as the amount of sleep they can get and the onset of postnatal depression.

The difficulty of weight management at this stage of the lifecycle should not be underestimated, given the many factors that influence a woman’s ability to engage in positive lifestyle behaviours, and careful consideration must be given to the design of interventions targeted at new mothers.

Weight-management interventions in the postpartum period

A number of systematic reviews examining effective strategies for weight loss in postpartum women have been published in the last decade and are summarised in Table 1 ( Reference Nascimento, Pudwell and Surita 17 – Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 , Reference Berger, Peragallo-Urrutia and Nicholson 68 – Reference Hoedjes, Berks and Vogel 71 ). The metrics used to assess effectiveness vary: differences in weight change between intervention and control groups are the most frequently reported primary outcome as well as the proportion of participants losing 5 or 10 % of body weight( Reference Nascimento, Pudwell and Surita 17 – Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 , Reference Berger, Peragallo-Urrutia and Nicholson 68 – Reference Hoedjes, Berks and Vogel 71 ). Alongside this, researchers also report other measures that may be more meaningful to participants themselves, such as the proportion of women returning to their pre-pregnancy weight, or less, after intervention, or the proportion of women meeting their own pre-specified weight-loss target after intervention( Reference Ferrara, Hedderson and Brown 72 ).

Table 1 Summary of systematic reviews examining strategies for weight loss in postpartum (PP) women

WL, weight loss; OW, overweight; OB, obese.

Overall, the quality of the trials included in these systematic reviews is mixed, with many trials lacking statistical power to fully evaluate effectiveness and nearly all studies failing to report method of randomisation and procedures for blinding of outcome assessments. Nonetheless, based on evidence to date, interventions including both diet and physical activity along with individualised support and self-monitoring are more likely to be successful in promoting postpartum weight loss( Reference Amorim Adegboye and Linne 18 , Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 , Reference Hoedjes, Berks and Vogel 71 ). Randomised controlled trials of exercise-only interventions are currently too limited to draw meaningful conclusions about the best ways to engage postpartum women in physical activity( Reference Nascimento, Pudwell and Surita 17 , Reference Berger, Peragallo-Urrutia and Nicholson 68 – Reference Choi, Fukuoka and Lee 70 ).

The most recent systematic review in this field by Lim et al. ( Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 ) explored lifestyle intervention strategies associated with weight loss in postpartum women. Out of twenty-two studies reporting body weight, nine (41 %) demonstrated a significant decrease in body weight compared with the control group. In meta-analyses, the lifestyle postpartum weight interventions significantly reduced body weight by 2·3 kg relative to control groups but there was significant heterogeneity in this analysis. Within this systematic review, the trial reporting the largest weight loss postpartum was a 12-week individualised structured diet and physical activity intervention( Reference O’Toole, Sawicki and Artal 73 ). At 1 year, the intervention group lost 7·3 kg and 6 % body fat relative to a loss of 1·3 kg and 1·5 % body fat in the control group; however, this was a small study (n 40) and only 65 % (thirteen out of twenty) of the intervention group and 50 % (ten out of twenty) of the control group completed the 1-year follow-up. Lim et al. ( Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 ) found that intervention setting (individual or group), intervention location (home-based or centre-based), type of media used as support (in-person only, telephone support, or telephone and web support combined) and the number of technology-based media used to provide support (less than three media or three or more media) had no significant effect on weight loss. They did find that a shorter duration (6 months or less) resulted in significantly greater weight loss compared with interventions of 6 months’ duration or more. However, this appeared to be largely driven by the aforementioned small trial( Reference O’Toole, Sawicki and Artal 73 ) that reported a large mean weight loss: the difference between shorter and longer intervention duration was no longer significant when this study was removed from the analysis. Therefore, to date, there is no consensus on the optimum intervention setting, duration and mode of delivery for postpartum weight loss.

Arguably, the most convincing trials in this field will be those that can demonstrate longer-term weight changes, i.e. continued weight loss or maintenance of weight loss in the long term rather than just short-term weight loss; a few studies have shown promise in this regard. Bertz et al. ( Reference Bertz, Brekke and Ellegard 74 ) conducted a factorial design study to investigate the effect of a 12-week diet, exercise, or diet and exercise combined behavioural modification intervention on body weight in lactating women and included a follow-up at 12 months (9 months after the intervention had ceased). Only the dietary intervention resulted in clinically relevant weight loss (9·7 % at 12 weeks and 11·8 % at 1 year). The intervention delivery consisted of: a one-to-one counselling session with a dietitian at the research clinic (1·5 h); a home visit half way through the intervention (1 h); and women were asked to report their weight biweekly via text message. The study had been carefully designed with due consideration of participant burden and the dropout rate was very low, indicating good acceptability for the intervention.

Two recent, year-long, trials have demonstrated the potential to use technology to support the delivery of interventions targeting women during the postpartum period. Nicklas et al. ( Reference Nicklas, Zera and England 75 ) adapted the Diabetes Prevention Program (an intensive face-to-face lifestyle intervention) into a web-based lifestyle intervention for postpartum women called ‘Balance after Baby’. Women who had GDM in their most recent pregnancy took part in the study (n 75; 57 % white; 34 % low income). As well as the web-based content, participants were also encouraged to contact a lifestyle coach weekly for the first 12 weeks of the intervention then every other week for weeks 13–24, and monthly for the last 6 months. Study participants were also given 10 months’ membership of the local YMCA as well as body weight scales, pedometers and measuring cups and spoons. The intervention group lost a mean of 2·8 kg between 6 weeks and 12 months postpartum compared with a gain of 0·5 kg in the control group. Phelan et al. ( Reference Phelan, Hagobian and Brannen 76 ) recently explored the addition of an Internet-based weight-loss programme to the US Women Infant and Children (WIC) programme for low-income women. They conducted a 12-month cluster randomized controlled trial comparing usual care (WIC programme) with the WIC programme plus the 12-month web-based weight-loss programme. Of the 391 women who took part in the study, 82 % were Hispanic and 50 % had a household income under 20 000 US dollars. The study completion rate was high (90 %); retention was possibly helped by payments for completion of study assessments at baseline, 6 and 12 months. The 12-month weight loss was significantly greater in the intervention group (mean weight loss 3·2 kg) compared with the standard care group (mean weight loss 0·9 kg) and 33 % of the intervention group returned to their preconception weight by 12 months compared with 19 % of the standard care group. The web-based programme consisted of weekly lessons, self-monitoring tools, a message board and monthly face-to-face visits held at WIC clinics. Both trials engaged women from across the socio-economic spectrum, indicating that these approaches show promise for hard-to-reach groups.

The trials above demonstrate the potential to positively influence postpartum body weight in the longer term but many gaps exist in the evidence base in this area. There is a need for more research to explore what the optimal setting, mode of delivery, recruitment approach (including optimal stage to engage postpartum women) and intervention duration are to achieve and maintain changes in lifestyle behaviours that promote weight loss, and maintenance of a healthy weight, at this life stage( Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 ). Intervention approaches that appeal to hard-to-reach groups who often have the highest need and are likely to benefit most are urgently required and this is a key consideration in order to ensure that well-intended programmes do not widen inequalities.

Setting and mode of delivery

New mothers face challenges engaging in behaviour change interventions, owing to the many demands of motherhood and the lifestyle restrictions that come with having a new baby, as discussed previously. As a result, some postpartum interventions have reported low intervention adherence and high attrition, thus raising concerns about reach and retention, particularly for disadvantaged groups( Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 , Reference O’Toole, Sawicki and Artal 73 , Reference Craigie, Macleod and Barton 77 – Reference Chang, Nitzke and Brown 82 ). An example of this is the Active Mothers Postpartum study; despite high initial motivation to enrol in the study( Reference Østbye, Krause and Lovelady 78 ), and even with the provision of group sessions, multiple times per week and at various times of day, women found it difficult to attend owing to the competing needs of their baby, home- and work-life. Thus, despite considerable evidence that group approaches are associated with significant weight loss in the general population( Reference Madigan, Daley and Lewis 83 ), they may not be appealing for many women during the postpartum period. Child-care issues and demanding care schedules dominate the postpartum period and so going out, whether that be to an exercise class or to a slimming group, is difficult for many women and this is a pivotal factor for intervention development in this field.

Overall, trials to date suggest that a highly flexible and individualised approach to weight-loss interventions is needed in the postpartum period, shifting away from structured community-based programmes, to home-based or more adaptable ‘anytime, anyplace’ approaches such as those enabled by telephone and Internet technologies( Reference Spencer, Rollo and Hauck 16 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 , Reference O’Toole, Sawicki and Artal 73 , Reference Craigie, Macleod and Barton 77 – Reference Macleod, Craigie and Barton 79 , Reference Herring, Cruice and Bennett 84 ). This approach may facilitate wider engagement, participation and reach, particularly for disadvantaged women with low levels of social support. Most interventions in postpartum women to date have largely been delivered by a range of professionals (for example, nurses, fitness instructors, dietitians, trained counsellors, study assistants) using a more traditional face-to-face approach, with very few using modern technologies such as the Internet and mobile telephones as a primary mode of delivery or as an adjunct to traditional face-to-face support. This is a promising avenue for exploration and many trials are underway that will start to test these alternative modes of engagement.

Unlike during pregnancy, women have few routine health appointments during the postpartum stage. In the UK and many other countries, women will have a 6-week postnatal appointment with their general practitioner to assess recovery from childbirth and contraception. This is generally a short appointment which does not lend itself easily to an extended discussion of the women’s wider health, including lifestyle and psychosocial aspects. Other than this postnatal appointment, women will come into contact with health visitors at key milestones in the babies’ development, for example, at immunisation appointments and for key developmental assessments. Although NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) recommends( 4 ) that general practitioners, health visitors and practice nurses should offer support with weight management after childbirth, it may be challenging for health professionals to add this to their already long list of duties and responsibilities. Research from cohorts of mothers in Australia( Reference Van der Plight, Olander and Ball 85 ) and North Carolina( Reference Ferrari, Siega-Riz and Evenson 86 ) indicates that women feel they receive much less physical activity and weight-loss advice after pregnancy than during pregnancy( Reference Van der Plight, Olander and Ball 85 ), with 89 % of women reporting they received no weight-loss advice from a healthcare provider during the first 3 months postpartum( Reference Ferrari, Siega-Riz and Evenson 86 ). Future studies should explore how health professionals would feel about giving such advice to postpartum women and what is the best way to do this in the face of short appointments and other competing priorities such as child safety. At the very least, any routine appointments with health professionals where women may come into contact with health professionals in the postpartum period could be utilised to signpost women to appropriate information sources and effective weight-management interventions.

Optimal stage to engage postpartum women

There is no consensus on the optimum time to engage women in postpartum weight management. In the trials included in the systematic review of Van der Plight et al. ( Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 ), the stage at which participants were recruited ranged from within 1–2 d following birth (24–48 h) to 3–12 months postpartum, and no clear pattern with stage of intervention commencement and intervention success was evident during the postpartum period. Engagement with women during pregnancy right through to the postpartum period may offer the best chance of long-term weight-management success, if issues around retention can be overcome( Reference Wilkinson, van der Plight and Gibbons 87 ). Alternatively, it may be the case that interventions that have flexibility regarding time to opt in may be more likely to have optimal reach for the reasons discussed in the sections above. Both of these recruitment approaches are worthy of investigation.

The recruitment approach used in different trials varies according to the post-birth recruitment window specified in a trial protocol and so can encompass recruitment via the health service as well as community-based recruitment approaches. Whatever the approach, lifestyle interventions have the potential to widen health inequalities( Reference Marmot, Goldblatt and Allen 88 ) and researchers should be cognisant of this when developing their recruitment strategy and ensure process evaluation measures( Reference Moore, Audrey and Barker 89 ) are in place to fully evaluate the reach and effectiveness of their methods across the socio-economic spectrum.

Engaging women during pregnancy may help instil positive habits in relation to diet and activity that are carried through to the postpartum stage and beyond. A small number of gestational weight-gain interventions in pregnancy have included follow-up into the postpartum period; however, these studies found no statistically significant difference between the intervention and standard maternity care groups for postpartum weight loss or PPWR( Reference Agha, Agha and Sandell 90 ).

Ideally, we need to work towards a scalable and sustainable portfolio of intervention strategies that start pre-conceptually, continue during pregnancy and are sustained well into the postpartum period in order to develop a seamless continuum of care for women. Offering women support with weight management during pregnancy that does not then continue into the postpartum stage of life is unlikely to lead to maintenance of behaviour change. Furthermore, women’s needs with regard to weight-management support may change from pregnancy to the postpartum stage, as discussed in the section on barriers above, and intervention approaches need to be designed with this in mind.

Intervention duration

Postpartum interventions to date have mostly been of 12–16 weeks’ duration, with few lasting for more than 6 months( Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 ). This is reflective of weight-loss research in general, which is dominated by trials of relatively short duration that focus only on weight loss. Whilst many intervention approaches may induce clinically relevant weight loss in the short term, much less is known about weight-loss maintenance (6 months and beyond)( Reference Avenell, Broom and Brown 91 – Reference Middleton, Patidar and Perri 93 ), which is key to maintaining clinical benefits( Reference Sniehotta, Simpson and Greaves 92 ). There is increasing recognition of the need for trials to focus attention on maintenance of weight loss and, importantly, for interventions to be designed specifically for this purpose( Reference Sniehotta, Simpson and Greaves 92 ). Careful consideration of the behaviour change theory that is used to inform the intervention design is needed to ensure it encompasses the processes that underpin initiation and maintenance of behaviour change( Reference Penn, White and Lindström 94 – Reference Sciamanna, Kiernan and Rolls 97 ). This theoretical basis is vital as it will direct the behaviour change techniques that are included within the intervention.

There are specific aspects of trial design that need to be considered in order to advance the field of postpartum weight-management research, namely: randomisation, blinding, attrition, engagement, identification of active ingredients in multi-component interventions, cost-effectiveness, and implementation research, as discussed below.

Previous trials in this field have scored poorly in evaluations of trial quality, particularly in the categories of failing to report the detail of the randomisation process and the approach to blinding outcome assessment( Reference Amorim Adegboye and Linne 18 , Reference Van der Plight, Wilcox and Hesketh 19 , Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 ). Frameworks exist to improve the reporting of trials and these should be consulted at the trial design stage to minimise risk of bias( Reference Boutron, Altman and Moher 98 ).

Weight-loss interventions in general are prone to high levels of attrition( Reference Moroshko, Brennan and O’Brien 99 ) and this is a particular issue for trials in postpartum women( Reference Berger, Peragallo-Urrutia and Nicholson 68 , Reference Phelan, Hagobian and Brannen 76 , Reference Madigan, Daley and Lewis 83 ). While many trials do achieve a retention of 70 % or greater, some trials have reported attrition rates as great as 53 %( Reference O’Toole, Sawicki and Artal 73 ). Attrition can affect study power, bias and generalisability( Reference Fewtrell, Kennedy and Singhal 100 ). The nature of the intervention and the research methodology itself can both influence attrition rates, i.e. women will drop out if they find it too difficult to engage with the intervention and/or they find the ‘research’ or data collection aspect burdensome because of the nature and quantity of outcomes being assessed and where the assessments are taking place. Just as women may struggle to be in a particular place at a particular time to engage with a weight-loss group or face-to-face session, equally they may struggle with the same issue if required to attend an appointment for study outcome assessment( Reference Wilkinson, van der Plight and Gibbons 87 ). Consideration of this is needed at the trial design stage and possible solutions, such as conducting study follow-up visits at the woman’s home and/or offering payments to compensate for time required for study visits, should be pilot tested in order to guide the design of future trials. The issue of differential attrition owing to dissatisfaction with being randomised to a usual-care group in a weight-loss trial is also important to consider as this has been observed in the postpartum setting( Reference Lim, O’Reilly and Behrens 35 , Reference Macleod, Craigie and Barton 79 , Reference Wilkinson, van der Plight and Gibbons 87 ) and can have a negative impact on trial outcomes( Reference McCambridge, Kypros and Elbourne 101 ). The nature of the study outcomes should be pilot tested to ensure they are acceptable for this group, for example, Craigie et al. ( Reference Craigie, Macleod and Barton 77 ) encountered difficulties in obtaining skinfold thickness and fasting blood samples in the WeighWell weight-loss intervention with postpartum women living in areas of social disadvantage. A compromise may have to be reached between what the researchers would ideally like to measure or assess and what is pragmatic for this population in terms of type of measures, frequency of measurement of outcomes and location where the measurements are collected.

One aspect that is currently lacking in interventions in the field of postpartum weight management is assessment of cost-effectiveness, which is vital to inform decisions around scale up and implementation and should be built in at the earliest stages of trial design. In addition to this, process evaluations( Reference Moore, Audrey and Barker 89 ) also provide key information about how, why and for whom an intervention works or does not work and will ultimately guide the pathway to implementation. A further key opportunity to advance this field is to ensure better description of intervention content. Weight-management interventions are typically multi-component and should follow best practice regarding the development, evaluation and reporting of complex behaviour change interventions in order to allow elucidation of the active ingredients( Reference Craig, Dieppe and Macintyre 102 ). Better description of intervention content( Reference Hoffmann, Glasziou and Boutron 103 ), including description of behaviour change techniques used in intervention and control groups using recognised taxonomies( Reference Michie, Ashford and Sniehotta 104 ), monitoring engagement with key components and including of mediator and moderator analysis will all advance this field in terms of understanding what works best and for whom.

Generating evidence of efficacy is only the first step to identifying solutions in this field; implementation research is needed to guide the adaptation of efficacy trials so they are ready for scale up and incorporation into existing antenatal and postnatal care pathways. This is a vital step towards influencing public health policy and practice. Further insights on this topic are provided by Horodyska et al. ( Reference Horodyska, Luszczynska and Hayes 105 ) who discuss a number of considerations for implementation of diet and physical interventions, whilst Harrison et al. ( Reference Harrison, Skouteris and Boyle 106 ) focus specifically on implementing research on preventing obesity across the preconception, pregnancy and postpartum cycle into practice.

Future research

Since postpartum women are difficult to reach and retain, future research must consider how to make weight-management interventions an attractive and attainable proposition for women who are juggling multiple, competing demands. Carefully designed, evidence and theory-based, high-quality trials are needed to advance this field. Ideally, intervention approaches need to be flexible and allow sustained contact over the medium to long term in order to facilitate a focus on maintenance of weight loss and also allow re-engagement with women after life events that may disrupt weight-management progress, such as illness and relationship difficulties. Feasibility and pilot studies are essential to test the acceptability of new intervention approaches and trials should include process evaluations( Reference Moore, Audrey and Barker 89 ) to aid interpretation of the primary outcome through consideration of factors such as success of recruitment strategies, acceptability of the intervention to women, fidelity of implementation and reasons for poor engagement or high attrition. When considering outcomes, in addition to the primary anthropometric outcomes, consideration should be given to examination of breast-feeding behaviour, maternal self-esteem, body image, and spill-over effects on family. However, participant burden remains a key consideration for postpartum interventions.

As with all public health interventions, ability to scale up in a cost-effective way is of paramount importance when it comes to identifying sustainable approaches to tackling the challenge of weight management after pregnancy. A number of weight-loss intervention trials are underway in postpartum women, as evidenced by the number registered on clinical trials websites. Many of these studies are using web- and mobile-based technology as a way of delivering the intervention or as a component of the intervention. Testing promising approaches such as this will help to unravel the key components associated with weight-loss success in this group. Ultimately, we need to generate a range of appealing and effective intervention options for postpartum women, as a one-size-fits-all approach is not a viable solution.

In addition to interventions, serial measurements of weight into the late postpartum phase in cohorts where women have had a baby will help better understanding of postpartum weight trajectories and determinants of PPWR v. weight gain during late postpartum period, particularly between 1 and 2 years postpartum and beyond. Also, epidemiological studies with more specific categorisation of ethnicities and racial groups are needed to fully explore pregnancy-related weight gain and loss in different cultures.

Conclusion

The topic of weight management in women is one of major public health importance as the impact of the obesity epidemic on the health of mothers and babies becomes apparent. Much of the research to date has focused on weight management during pregnancy but there is increasing recognition of the importance of correcting weight before and between pregnancies. Women are at increased risk for weight gain during the reproductive years and, for some, the childbearing years can set women on an upwards weight trajectory for the decades ahead. The postpartum period is an opportune time to intervene to shape new health behaviours as there may be heightened awareness about health at this time. However, the postpartum period is also a challenging time to intervene owing to the major physiological, psychological, and social changes taking place in the lives of new mothers.

There is significant variability in postpartum weight trajectories between women and it is likely that new mothers will be ready to engage with weight-management interventions at different stages after birth. Interventions that have flexibility regarding time to opt in may be more likely to have optimal reach, but this is something that needs to be tested in trials that allow opt in over a wider postpartum period.

Systematic reviews indicate that interventions including both diet and physical activity along with individualised support and self-monitoring are more likely to be successful in promoting postpartum weight loss. High levels of attrition and poor engagement have been an issue in previous trials in this area. The difficulty of weight management at this stage of life should not be underestimated and careful consideration must be given to the design of interventions targeted at new mothers in order to identify the most appropriate settings and methods of supporting weight loss post-pregnancy. What works at other life stages may not necessarily work here owing to specific barriers to weight management encountered in the postpartum period.

Acknowledgements

M. C. M. drafted the manuscript; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interests to declare.