Introduction

The worldwide ageing population has increased, with the number of older people aged 65 years and older predicted to double to 1·5 billion in 2050(1,2) . Even though there has been an increase in average life expectancy, the health span, or period of life during which individuals are in good health, has not mirrored the same trajectory(Reference Kalache, de Hoogh and Howlett3). As a result, interest in promoting healthy ageing is growing.

Older adults remain a vulnerable population prone to malnutrition(Reference Cereda, Pedrolli and Klersy4), defined by the World Health Organization as ‘deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients’(5). Both caloric excess and nutrient inadequacy have been shown to be associated with increased risks of age-related chronic diseases and mortality(Reference Kalache, de Hoogh and Howlett3,Reference Bowman, Delgado and Henley6) . There is accumulating evidence to suggest that prevalence of obesity among older adults is increasing(Reference Decaria, Sharp and Petrella7–Reference Ma, Xi and Yang9), and saturated fats, trans fat, added sugars and sodium have been found to be consumed in excess by older adults(Reference Tucker10,Reference Choi, Crimmins and Kim11) . Risk of protein-energy malnutrition is also prevalent in older adults. A recent systematic review of 240 studies using the Mini Nutritional Assessment estimated that those at risk of protein-energy malnutrition range from 27 % (community) to 50 % (other healthcare settings) of populations(Reference Cereda, Pedrolli and Klersy4). Among older adults, the prevalence of sarcopenic obesity appears to be increasing, with its effects on functional decline, cardiometabolic diseases and mortality potentially more pronounced than sarcopenia or obesity alone(Reference Roh and Choi12).

A 2015 systematic review of 37 studies from 20 different countries indicates that community-dwelling older adults do not meet the estimated average requirement of essential nutrients, including vitamin D, thiamin, riboflavin, calcium, magnesium and selenium(Reference Ter Borg, Verlaan and Hemsworth13). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data show that more than 40 % of the US population, aged 51 years and over, did not meet the estimated average or adequate intake for nutrients, including fibre, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, calcium, potassium, and vitamins C, A, D, E and K(Reference Bruins, Bird and Aebischer14). Another recent US study of 5614 community-dwelling older adults found that almost 90 % had poor-quality diets, with more than 50 % not meeting most dietary guidelines for food groups and nutrients(Reference Choi, Crimmins and Kim11). A higher proportion of institutionalised older adults (35 %) also consume less than the estimated average requirements of protein when compared with community-dwelling and frail elderly (10 %)(Reference Tieland, Borgonjen-Van den Berg and van Loon15).

Healthy dietary patterns are associated with improved quality of life(Reference Govindaraju, Sahle and McCaffrey16), self-rated health(Reference Govindaraju, Sahle and McCaffrey16), better health outcomes(Reference Milte and McNaughton17) and reduced mortality(Reference Russell, Flood and Rochtchina18) among older adults. These healthy dietary patterns are generally rich in plant foods, with a strong focus on the inclusion of vegetables, legumes, fruits and whole grains, with adequate protein intake and lower intakes of meats and processed foods(Reference Chen, Maguire and Brodaty19). This results in higher intake of polyphenols, antioxidants and fibre, compounds associated with reduced inflammation(Reference Wu, Chen and Tsai20,Reference Medawar, Huhn and Villringer21) and oxidative stress(Reference Aleksandrova, Koelman and Rodrigues22), with the potential to modulate ageing-related biological pathways(Reference Medawar, Huhn and Villringer21). Plant-rich diets have been linked to longer telomere length, an indicator of ageing phenotype and disease risk, in observational studies(Reference Crous-Bou, Molinuevo and Sala-Vila23). Diet also plays a role in the prevention of sarcopenia(Reference Bauer, Biolo and Cederholm24,Reference Bloom, Shand and Cooper25) , and healthy diet patterns have been associated with lower odds of frailty by a 2019 systematic review of 13 observational studies(Reference Rashidi Pour Fard, Amirabdollahian and Haghighatdoost26). In addition, systematic reviews show that healthy diets such as the Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diets may protect against cognitive decline in ageing(Reference Chen, Maguire and Brodaty19,27–Reference van den Brink, Brouwer-Brolsma and Berendsen29) .

Poor nutritional intake and unhealthy dietary patterns among older adults are influenced by multifactorial determinants(Reference Clegg and Williams30). Contributing factors include chronic health conditions, social isolation(Reference Porter Starr, McDonald and Bales31), low socioeconomic status(Reference Nazri, Vanoh and Leng32), limited healthy food accessibility(Reference Choi, Crimmins and Kim11) and financial burden(Reference Turconi, Rossi and Roggi33). Poor nutritional intake can also be attributed to age-related physiological and functional changes such as poor appetite(Reference Clegg and Williams30), early satiety(Reference Fávaro-Moreira, Krausch-Hofmann and Matthys34), hypogeusia, anosmia(Reference Brownie35) and dental issues(Reference O’Connor, Milledge and O’Leary36). Hospitalised elderly patients are susceptible to disease-related undernutrition due to loss of appetite leading to poor oral nutritional intake(Reference Bounoure, Gomes and Stanga37) and weight loss exacerbated by acute illness(Reference Dent, Hoogendijk and Visvanathan38). In nursing homes, poor nutrition is commonly associated with cognitive and functional impairments, swallowing difficulty and depression(Reference Bell, Lee and Tamura39). Overall, prolonged poor nutritional intake among older adults is associated with reduced health-related quality of life and increased mortality(Reference Wei, Nyunt and Gao40).

Unfortunately, older people often fail to recognise that they are at risk of poor nutrition(Reference Thompson Martin, Kayser-Jones and Stotts41). Nutrition knowledge, defined as the individual cognitive processes used to identify facts associated with diet, food, nutrition and its effects on the human body(Reference Barbosa, Vasconcelos and Correia42,Reference Zeldman and Andrade43) , has been shown to impact dietary behaviours. A systematic review by Barbosa et al. (2016) identified 6 of 10 studies demonstrated positive associations between nutrition knowledge and healthy eating habits including increased fruit and vegetable intake, and lower intake of fat, salt and simple sugars(Reference Barbosa, Vasconcelos and Correia42). Another systematic review by Spronk et al. (2013) investigated the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake, and found that the majority of studies reported weak (r < 0·5) but significant positive correlations(Reference Spronk, Kullen and Burdon44). Furthermore, participants of lower socioeconomic status were underrepresented in this review, which may have impacted the strength of association. Nevertheless, theoretical models of behaviour change exist which describe the strategies used to elicit behaviour change such as a change in eating behaviour. These include models such as the health belief model, social cognitive theory and the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour (COM-B) model by Michie et al. (Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West45). All of these models describe knowledge as a required precursor to action(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West45–Reference MacNab, Davis and Francis47). Although nutrition knowledge itself may not be sufficient to elicit change in eating behaviour, it is a requirement for behaviour change to occur(Reference Barbosa, Vasconcelos and Correia42,Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West45,Reference López-Hernández, Martínez-Arnau and Pérez-Ros48,Reference Worsley49) .

Although nutrition knowledge is important, older adults are known to have poorer nutrition knowledge compared with younger adults(Reference De Morais, Oliveira and Afonso50). Educational interventions have the potential to improve nutritional status, especially when coupled with behaviour change techniques, although there is only low quality of evidence from current studies due to methodological limitations(Reference Rea, Walters and Avgerinou51–Reference Baranowski, Ryan and Hoyos-Cespedes54).

Caregivers also have an important role in the care of older adults, as receiving help from caregivers is common in the older age groups owing to functional impairments(Reference Araujo de Carvalho, Epping-Jordan and Pot55). Nutrition education interventions for caregivers to improve nutrition knowledge have been associated with improved dietary habits(Reference Fernández-Barrés, García-Barco and Basora56,Reference Marshall, Agarwal and Young57) and can potentially improve or maintain nutritional status and reduce decline in dietary intake and malnutrition risk among older adults. Additionally, nutrition knowledge of healthcare professionals strongly influences their nutrition care practice and quality of nutrition education provided to their patients(Reference Zeldman and Andrade43,Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Pavlovic58) . Thus, ensuring adequate nutrition knowledge among older adults and their caregivers represents an important step in the process of facilitating and maintaining health.

To reliably assess and compare nutrition knowledge among individuals, determine the effectiveness of nutrition interventions and identify gaps in nutritional knowledge, nutrition knowledge assessment tools (NKATs) are required. Gaining a deeper insight into the gaps in nutrition knowledge of individuals enables the development of more effective nutrition education programmes and interventions(Reference Hendrie, Cox and Coveney59).

A 2016 systematic review found 25 studies that used questionnaires to assess adults’ nutrition knowledge(Reference Barbosa, Vasconcelos and Correia42). Another 2020 systematic narrative review identified 33 validated instruments for the assessment of nutrition knowledge of physicians and nurses(Reference Zeldman and Andrade43). However, neither review focused on older adults, and to our knowledge, no study has investigated tools developed to assess general nutrition knowledge for older adults or their carers. Hence, the objective of this scoping review is to investigate tools used to assess general nutrition knowledge of older adults and of their carers across all settings of care.

Methods

Scoping reviews seek to map a topic within existing literature; summarise and disseminate research findings; or identify research gaps within a wide range of sources and study designs(Reference Arksey and O’Malley60). The framework described by Arksey and O’Malley guided the methodological processes used in this scoping review, which comprised 5 stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results(Reference Arksey and O’Malley60). This review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines for scoping reviews(Reference Peters, Marnie and Tricco61), and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin62).

Identifying the research question

The research question was defined as ‘What tools are available to assess general nutrition knowledge of older individuals or their carers?’. Sources were included if they met all of the following eligibility criteria:

-

1) Older adult population or subpopulation (adults ≥ 60 years old or mean age ≥ 65 years) or their formal (professional caregivers) or informal (family or friends) carers;

-

2) The tool predominantly (≥50 %) assesses general nutrition knowledge using quantitative measures;

-

3) NKATs can be sourced with all items specified within the paper, supplementary material or reference list;

-

4) Any setting including community homes or other institutions (including nursing homes and hospitals);

-

5) Any study design available in full text and written in English.

We defined general nutrition knowledge as including a range of knowledge on topics such as expert and government dietary recommendations, portion sizes, food groups, nutrient health benefits and sources, healthier food and meal alternatives, relationships between diet and disease, and knowledge to discern common nutritional myths and facts(Reference Barbosa, Vasconcelos and Correia42). We excluded studies with a sole focus on specific nutritional topics (e.g. heart disease, osteoporosis or protein-energy malnutrition) or food type (e.g. legumes, dairy foods or whole grains). For this study, NKATs were defined as any instruments developed for the purpose of assessing nutrition knowledge including tools used before and/or after education sessions, and included questionnaires, interviews, surveys, tests, indices, scales and checklists. It was not a requirement for the tool to be validated for inclusion owing to the explorative purpose of this scoping review, although the validation status of each tool was specified. Where reference was made to a NKAT developed or included in another article, the article was sought and included if it satisfied the eligibility criteria. Hence, original tools of modified versions were also included if the full tool was available within the original paper or as supplementary material.

Identifying relevant studies

A 3-step search strategy(Reference Peters, Marnie and Tricco61) was adopted and conducted by 2 researchers. An initial scoping search on MEDLINE and CINAHL was conducted to gain familiarity with the scope of literature and identify relevant key search terms (online Supplementary Material 1) for the development of a search strategy. Following review of the search strategy by an experienced librarian, a comprehensive electronic database search was conducted from their inception until September 2020 across the following databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, Global Health and Embase (see online Supplementary Material 2 for the final MEDLINE search strategy). A second search was conducted from September to November 2020 to further identify potentially relevant sources.

In addition to academic databases, a range of search strategies were developed and conducted in September 2020 across a number of grey literature search engines and databases, including Google and Google Scholar (online Supplementary Material 3). An examination of the reference lists from relevant sources was also undertaken.

Study selection

Records were imported to a reference manager (EndNote, version X9). Single screening of the articles’ title and abstract was conducted, followed by retrieval and further screening of full texts of eligible articles by 2 reviewers. Additional sources found through grey literature databases and reference lists were subjected to the same study selection process as the academic database sources. Any disagreements from the screening process were discussed and amended by consensus or further adjudication by a third reviewer. In cases where the full tool was not provided, authors were contacted for the full tool to evaluate whether the tool meets the eligibility criteria for inclusion.

Charting the data

Relevant information from included studies was extracted independently by 2 reviewers using a data charting form. Charted information was then cross-checked to ensure all necessary details were accurate. Authors were contacted for additional details that may not have been reported in the paper, including pilot testing and psychometric properties of the tool. Any disagreements were discussed or resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. The following data were charted: article features (author, year, country), population (older adults or carers), context (community- or institution-based) and features of the NKAT (name, design purpose, details of development or modification, content, structure, number of items, validity and reliability of tool).

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Information from the data charting form was synthesised into a summary table. Studies were categorised based on the target population of the NKAT (i.e. older adults or carers). Information regarding the development, validity and reliability of each NKAT was classified according to key methodological processes and expert recommendations for developing and validating nutrition knowledge questionnaires, as outlined and summarised by Trakman et al. (2017)(Reference Trakman, Forsyth and Hoye63). The table of charted information included: author(s); year; country; type of setting; NKAT; target population; aim of tool; structure, content and method of administration of tool; development, modification and pilot testing of tool; validity and reliability of tool.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

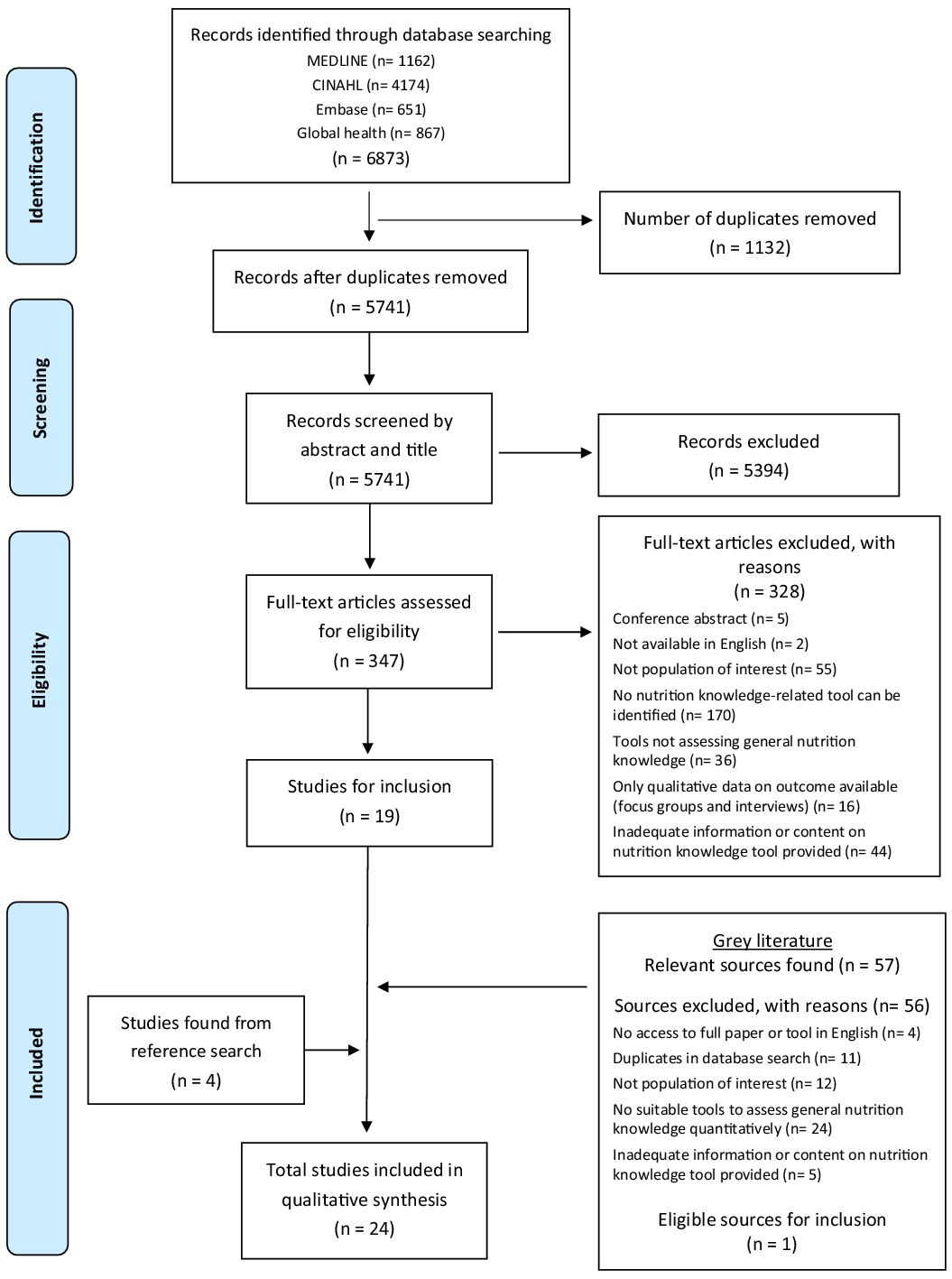

A total of 6934 articles were identified, that is, 6873 references from the database search, in addition to 57 grey literature sources and 4 articles from the reference list search. This resulted in a total of 24 articles, of which 23 NKATs were included in qualitative synthesis(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64–Reference Wang, Yang and Hu87). The selection process of sources of evidence has been summarised in Fig. 1. Most studies were conducted in the United States(Reference Crogan66–Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69,Reference Mann, Hildreth and Draughn73,Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75,Reference Pogge and Eddings78,Reference Rosenbloom, Kicklighter and Patacca79,Reference Shannon and Pelican81,Reference Thomas, Almanza and Ghiselli83,Reference Howard, Gates and Ellersieck86) , followed by Australia(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64,Reference Brennan, Singh and Brennan71) and the UK(Reference Moynihan, Mulvaney and Adamson74,Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle76) , and Israel(Reference Boaz, Rychani and Barami65), Scotland(Reference Anderson, Umapathy and Palumbo70) Singapore(Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72), Canada(Reference Southgate, Keller and Reimer82), France(Reference Rousset, Droit-Volet and Boirie80) and Korea(Reference Yu and Kim84). Table 1 summarises the tool characteristics of included studies.

Fig 1. PRISMA diagram.

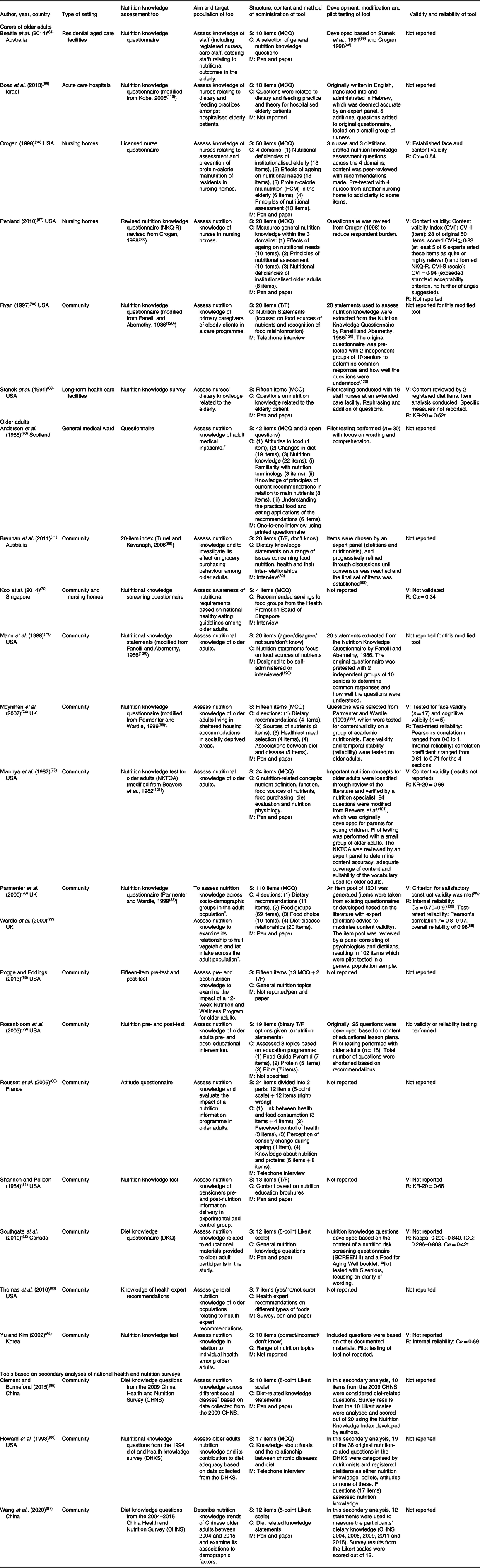

Table 1. Summary of included studies with nutrition knowledge assessment tools(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64–Reference Wang, Yang and Hu87)

C, content; Cα, Cronbach’s alpha; ICC, intraclass correlation; KR-20, Kuder-Richardson 20 coefficient; M, method of administration; MCQ, multiple choice questions; R, reliability; S, structure; T/F, V, validity.

* Indicates that a subpopulation of the study were older adults.

† Reported as adequate or relatively reliable by the author.

The primary aim of NKATs varied depending on the purpose of the study. Although most studies generally aimed to assess nutrition knowledge of older adults(Reference Anderson, Umapathy and Palumbo70,Reference Mann, Hildreth and Draughn73–Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle76,Reference Yu and Kim84) or their carers(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64–Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69) in different contexts, some studies specifically used NKATs to assess change in nutrition knowledge in order to measure the impact of interventions or programmes(Reference Pogge and Eddings78–Reference Southgate, Keller and Reimer82); investigate the relationship between nutrition knowledge and behaviour(Reference Brennan, Singh and Brennan71,Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller77) ; assess awareness of national dietary guidelines or health expert recommendations(Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72,Reference Thomas, Almanza and Ghiselli83) ; or assess knowledge based on nutrition-related responses collected from population health surveys(Reference Clement and Bonnefond85–Reference Wang, Yang and Hu87).

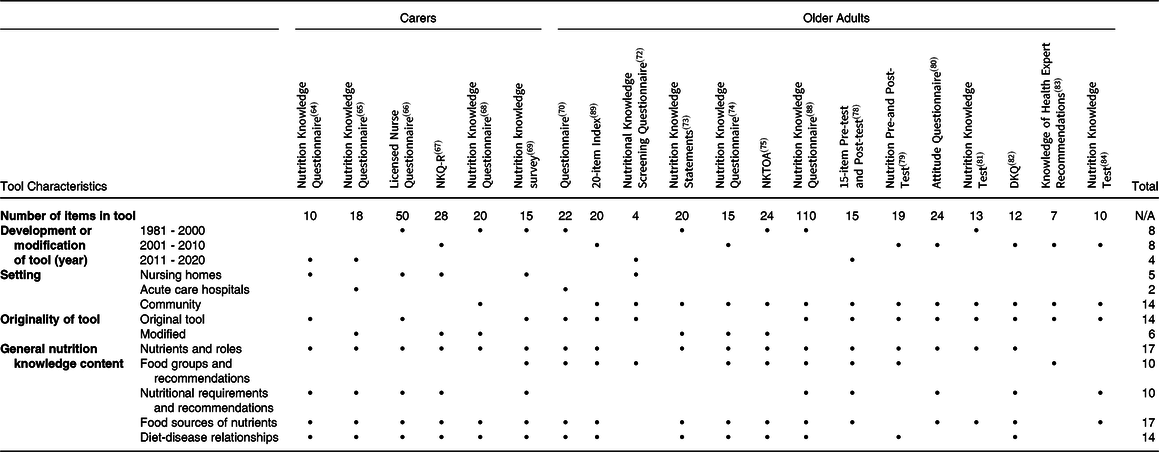

Of the total 23 NKATs, the majority of tools were designed for older adults (n = 17), while 6 tools were for carers of older adults, of which 4 were developed specifically for nurses. NKATs were either (i) original or modified versions of original tools (n = 20), or (ii) based on secondary analyses of national health and nutrition surveys (n = 3).

(i) Original and modified nutrition knowledge assessment tools

Table 2 provides a summary of key characteristics of each NKAT. 20 NKATs were either developed by the authors of the study(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64,Reference Crogan66,Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69,Reference Anderson, Umapathy and Palumbo70,Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72,Reference Pogge and Eddings78–Reference Yu and Kim84) , developed by other authors(Reference Parmenter and Wardle88,Reference Turrell and Kavanagh89) , or adapted or modified from pre-existing tools(Reference Boaz, Rychani and Barami65,Reference Penland67,Reference Ryan68,Reference Mann, Hildreth and Draughn73–Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75) . 8 NKATs were developed or modified prior to the year 2000(Reference Crogan66,Reference Ryan68–Reference Anderson, Umapathy and Palumbo70,Reference Mann, Hildreth and Draughn73,Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75,Reference Shannon and Pelican81,Reference Parmenter and Wardle88) , 8 between 2001 and 2010(Reference Penland67,Reference Moynihan, Mulvaney and Adamson74,Reference Rosenbloom, Kicklighter and Patacca79,Reference Rousset, Droit-Volet and Boirie80,Reference Southgate, Keller and Reimer82–Reference Yu and Kim84,Reference Turrell and Kavanagh89) , and more recently, 4 between 2011 and 2020(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64,Reference Boaz, Rychani and Barami65,Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72,Reference Pogge and Eddings78) . The NKATs varied in the number of items, ranging from 4 to 110 items each.

Table 2. Summary of key characteristics of original and modified nutrition knowledge assessment tools(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64–Reference Anderson, Umapathy and Palumbo70,Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72–Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle76,Reference Pogge and Eddings78–Reference Yu and Kim84,Reference Turrell and Kavanagh89)

N/A, not applicable.

Community-based settings represented the focus of most NKATs(Reference Ryan68,Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72–Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75,Reference Pogge and Eddings78–Reference Yu and Kim84,Reference Parmenter and Wardle88,Reference Turrell and Kavanagh89) . Within institutional care settings, only 5 tools were developed for use in nursing homes(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64,Reference Crogan66,Reference Penland67,Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69,Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72) , and 2 for acute care settings(Reference Boaz, Rychani and Barami65,Reference Anderson, Umapathy and Palumbo70) .

Multiple-choice questions represented the most commonly used tool structure among the NKATs. Other structure types included questions with binary options (true/false or agree/disagree to nutrition statements) and Likert scales.

The most common topics for general nutrition knowledge questions across all tools were related to: nutrients and roles (e.g. benefits of vitamin E(Reference Penland67)), food sources of nutrients (e.g. food sources of vitamin C(Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75)), diet–disease relationships (e.g. diseases related to the amount of fat(Reference Moynihan, Mulvaney and Adamson74); effect of fibre intake on constipation(Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75)), food groups and recommendations (e.g. recommended daily number of servings of vegetables(Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72); recommended intake of milk and dairy products for older adults(Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69)), and nutritional requirements and recommendations (e.g. changes in calcium requirements for older adults(Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69); nutritional requirements for nursing home residents to promote healing of pressure ulcers(Reference Crogan66)).

The majority of tools assessed a broad range of general nutrition topics (4 or more)(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64–Reference Penland67,Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69,Reference Anderson, Umapathy and Palumbo70,Reference Moynihan, Mulvaney and Adamson74,Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75,Reference Pogge and Eddings78,Reference Southgate, Keller and Reimer82,Reference Parmenter and Wardle88,Reference Turrell and Kavanagh89) , although 2 NKATs assessed only knowledge on food groups and recommendations(Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72,Reference Thomas, Almanza and Ghiselli83) .

(ii) Tools based on secondary analyses of national health and nutrition surveys

3 secondary analyses of large national health and nutrition surveys were considered separately to the tools described above. In these cases, survey responses from a section of a larger survey were extracted with the purpose of assessing nutrition knowledge. Such secondary analyses involved the development of a distinctive scoring system which enabled nutrition knowledge of respondents to be determined.

The China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) consisted of a 12-item section with 10 diet-related knowledge statements and 2 physical activity-related statements. Adult participants expressed their degree of agreement to the statements on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). The information collected from the responses was analysed by Clement and Bonnefond (2015)(Reference Clement and Bonnefond85) to compare nutrition knowledge across different social classes based on the 2009 CHNS. In a similar approach, Wang et al. (2020)(Reference Wang, Yang and Hu87) performed a secondary analysis to describe nutrition knowledge trends and to examine associations between demographic factors and nutrition knowledge, based on responses of older adults from the 2004–2015 CHNS.

Similarly, the 1994 Diet and Health Knowledge Survey (DHKS) directed by the United States Department of Agriculture contained 36 nutrition-related questions. 5 questions, consisting of 17 items, were determined by Howard et al. (1998)(Reference Howard, Gates and Ellersieck86) to assess nutrition knowledge. The data provided by the older adult population in response to the specific items were analysed to determine their nutrition knowledge and its relationship to diet adequacy.

Psychometric properties of nutrition knowledge assessment tools

With regard to original and modified NKATs, psychometric properties of validity were provided for 6 (26 %) NKATs and reliability for 9 (38 %) NKATs (Table 1). The extent to which validity and reliability of these tools were measured and tested was varied but limited. For instance, the majority of tools were pilot tested in a small sample of the target population(Reference Boaz, Rychani and Barami65,Reference Crogan66,Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69,Reference Anderson, Umapathy and Palumbo70,Reference Mann, Hildreth and Draughn73,Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75,Reference Rosenbloom, Kicklighter and Patacca79,Reference Southgate, Keller and Reimer82,Reference Yu and Kim84,Reference Parmenter and Wardle88) ; however, only 1 tool was reviewed by an expert panel but without details of content validity provided(Reference Turrell and Kavanagh89). Of 6 NKATs that were tested for validity, content validity was most commonly reported(Reference Crogan66,Reference Penland67,Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69,Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75,Reference Parmenter and Wardle88) , followed by face validity(Reference Crogan66,Reference Moynihan, Mulvaney and Adamson74)) , cognitive validity(Reference Moynihan, Mulvaney and Adamson74) and construct validity(Reference Parmenter and Wardle88).

Less than half the NKATs that were tested for internal consistency reliability (determined by Cronbach’s alpha (Cα) and Kuder–Richardson 20 (KR-20) coefficients)(Reference Crogan66,Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69,Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72,Reference Moynihan, Mulvaney and Adamson74,Reference Mwonya, Ralston and Beavers75,Reference Shannon and Pelican81,Reference Southgate, Keller and Reimer82,Reference Yu and Kim84,Reference Parmenter and Wardle88) had values below the cut-offs considered adequate, except for the Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire by Parmenter and Wardle, which achieved adequate internal reliability(Reference Parmenter and Wardle88).

The secondary analyses(Reference Clement and Bonnefond85–Reference Wang, Yang and Hu87) relied on different indices or scoring systems to assess nutrition knowledge, although no reliability or validity metrics specific to the components that assessed nutrition knowledge were reported.

Discussion

This is the first scoping review conducted to explore tools to assess the general nutrition knowledge of older people and their carers. Our findings identified 24 relevant sources with 23 different NKATs (including 3 secondary analyses). The format and structure of the NKATs, as well as the type and breadth of general nutrition topics assessed, differed substantially across the tools. NKATs also generally lacked validity and reliability testing.

The majority of NKATs found in our scoping review assessed knowledge of older adults in the community. The importance of older adults’ nutrition knowledge has been highlighted by 3 large cross-sectional studies which showed associations of older adults’ nutrition knowledge and healthy dietary intake. Wardle et al. (2000) found that, out of 1040 adult respondents (with 23 % of respondents over 65 years of age) in England, those in the highest knowledge quintile were almost 25 times more likely to meet recommendations for fruit, vegetable and fat intake than those in the lowest quintile(Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller77). A National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(Reference Vaudin, Wambogo and Moshfegh90) found that adults aged 60 years and older (n = 3056) with nutrition information awareness and application had higher diet quality. Taiwan participants aged over 65 (n = 1937)(Reference Lin and Ya-Wen91) who completed the Elderly Nutrition and Health Survey had inadequate knowledge, especially about nutrition and disease and restricted their diets based on traditional practices.

Only 1 NKAT(Reference Ryan68) was found for caregivers of older adults in the community. Home-based or domiciliary caregivers play a crucial role in the nutritional care of older adults, which often involve monitoring of dietary intake and hydration, shopping assistance, meal preparation and feeding when necessary(Reference Marshall, Agarwal and Young57). These caregivers spend more time providing care than healthcare professionals(Reference Iizaka, Okuwa and Sugama92) and may also be better positioned to provide nutrition care for community-dwelling older adults owing to greater awareness of individual needs, preferences and beliefs that could be overlooked by paid caregivers(Reference Marshall, Agarwal and Young57). This, coupled with the finding that carers of community-dwelling older adults lacked adequate dietary knowledge(Reference Avgerinou, Bhanu and Walters93), makes assessment of caregivers’ nutritional knowledge also crucial. NKATs developed for caregivers within community-based settings could assist in identification of knowledge gaps and misperceptions, which would be useful in guiding nutrition education programmes to optimise nutritional care and health outcomes of older adults.

With the exception of the Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire used by Beattie et al. (2014)(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64), no other NKAT intended for carers other than nurses in institutional settings, such as physicians, allied health professionals or food service staff, was found. Healthcare professionals are more likely to interact with patients within institutional settings and therefore have an important role in the nutrition care of older adults. Insufficient knowledge among healthcare professionals in hospital units has been cited as the main barrier for good nutritional management, with 25 % of doctors and nurses reported to have difficulty in identifying undernourished patients requiring nutritional therapy(Reference Mowe, Bosaeus and Rasmussen94). A systematic review by Zeldman and Andrade (2020)(Reference Zeldman and Andrade43) that assessed physicians’ and nurses’ knowledge of nutrition for adults over 18 years found mean nutrition knowledge scores from 32·5 % (poor) to 72 % (fair), and found scores were lowest for questions related to topics of nutrient digestion, absorption and metabolism, as well as nutrition in chronic diseases and conditions. Studies assessing knowledge regarding specific needs of older adults were not found in this 2020 review(Reference Zeldman and Andrade43). There is evidence to suggest that adequate healthcare professionals’ nutrition knowledge and awareness of nutritional consequences faced by older people, as assessed by NKATs, does in fact facilitate appropriate nutrition care and prevent poor nutrition(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Pavlovic58).

Given that protein-energy malnutrition rates are estimated to be higher in long-term care or rehabilitation hospitals (29 %), hospitals (22 %) and nursing homes (17·5 %) when compared with community settings (3 %)(Reference Cereda, Pedrolli and Klersy4), NKATs developed to assess knowledge specific to protein-energy malnutrition, are also needed. Our scoping review assessed tools about general nutrition knowledge and was not specifically focused on protein-energy malnutrition. Few NKATs incorporating questions related to protein-energy malnutrition in older adults(Reference Beattie, O’Reilly and Strange64,Reference Penland67,Reference Crogan and Evans95) were identified. Koo et al. (2014) found knowledge of daily nutritional requirements was not related to protein-energy malnutrition risk in older adults, but their tool did not include questions related to protein-energy malnutrition(Reference Koo, Kang and Auyong72). Specific tools such as the Knowledge of Malnutrition – Geriatric (KoM-G) questionnaire, validated for use in nursing homes(Reference Schönherr, Halfens and Lohrmann96), may be more suitable to assess nutrition-related knowledge of carers of older adults working within institutions. However, given the increasing rates of sarcopenic obesity and associated risks of functional decline(Reference Koliaki, Liatis and Dalamaga97) as well as beneficial cognitive impacts of diet(27), a focus on assessing general nutrition knowledge is still recommended.

In this scoping review, we found that the majority of NKATs for older adults and their carers were outdated, having been either developed or modified over 10 years ago. The recognition of the role of diet and its contribution to ageing, the characterisation of ageing syndromes such as frailty and sarcopenia, and the role of diet in reducing the risk of cognitive decline indicate updates to NKATs are needed(Reference Chen, Maguire and Brodaty19,Reference Bloom, Shand and Cooper25,Reference Rashidi Pour Fard, Amirabdollahian and Haghighatdoost26) . In addition, recent progress and developments within the food industry have led to increased food variety and accessibility(Reference Kliemann, Wardle and Johnson98). Over the past decade, major changes in food consumption trends such as fad diets (e.g. gluten-free and paleo diets(Reference Zopf, Reljic and Dieterich99)), functional foods(Reference Sloan100), and food takeaway and delivery(Reference Keeble, Adams and Sacks101) have emerged. Additionally, advances in nutritional science and the understanding of diet and health continually inform dietary recommendations, guidelines and policies(Reference Kliemann, Wardle and Johnson98,Reference Volkert, Beck and Cederholm102,103) . This includes associations between trans fats and coronary heart disease(Reference Brownell and Pomeranz104), the benefits of higher protein consumption in acute and chronic illness(Reference Bauer, Biolo and Cederholm24) and lower mortality among older people with higher BMI(Reference Javed, Aljied and Allison105,Reference Winter, MacInnis and Wattanapenpaiboon106) . Further, increased production and availability of ultra-processed foods has led to higher consumption of these foods(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Moubarac107), and has been associated with abdominal obesity(Reference Sandoval-Insausti, Jiménez-Onsurbe and Donat-Vargas108), incident dyslipidaemia(Reference Donat-Vargas, Sandoval-Insausti and Rey-García109) and frailty risk(Reference Sandoval-Insausti, Blanco-Rojo and Graciani110) among older adults. The need to revise outdated NKATs has been recognised(Reference Volkert, Beck and Cederholm111) and is evident with the example of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire by Parmenter and Wardle (1999)(Reference Parmenter and Wardle88), which was revised by Kliemann et al. (2016)(Reference Kliemann, Wardle and Johnson98) (GNKQ-R) to ensure questions were up to date with current dietary recommendations for the general adult population. Similarly, it is suggested that existing NKATs developed prior to year 2000 should be revised and re-validated to confirm that questions in such tools are reflective of current food trends, nutrition evidence and nutritional priorities.

Ultimately, our findings indicate little recent research in the development and validation of NKATs with a primary focus on the assessment of general nutrition knowledge in older adults or their carers. It is essential that NKATs are validated and reliable, to confirm that the tools are measuring what they intend to measure(Reference Trakman, Forsyth and Hoye63). Ideally, NKATs should meet psychometric properties of reliability, as well as construct and content validity(Reference Heaney, O’Connor and Michael112), such as with the application of the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) methodology to standardise and assess what constitutes good content validity(Reference Terwee, Prinsen and Chiarotto113). However, our findings show that the majority of NKATs were not validated or tested for reliability, or had inconsistencies in measures used to test psychometric properties. Kouvelioti and Vagenas (2015)(Reference Kouvelioti and Vagenas114) also reported similar issues where 70 % of tools assessing nutrition knowledge of athletes and coaches lacked validity and reliability. Likewise in a more recent review, Newton et al. (2019) reported about 69 % of NKATs used in school-based settings developed for pre-adolescents and adolescents were not validated, with 60 % without reliability testing(Reference Newton, Racey and Marquez115). Similarly, Spronk et al. (2014) reported 8 of 29 (28 %) studies investigating the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake used validated NKATs(Reference Spronk, Kullen and Burdon44), whereas Tam et al. (2019) detailed only 15·6 % of studies used well-validated NKATs to evaluate effectiveness of education interventions on nutrition knowledge(Reference Tam, Beck and Manore116). Lack of reliability and validity testing of NKATs was most likely attributed to the resource- and time-intensive process that comes with validating questionnaires(Reference Trakman, Forsyth and Hoye63). In addition, the reliability of some NKATs included in this review was reported as adequate by some studies(Reference Stanek, Powell and Betts69,Reference Southgate, Keller and Reimer82) despite coefficient values not meeting the cut-offs commonly considered adequate in the literature(Reference Trakman, Forsyth and Hoye63). This may be due to limitations associated with the use of these statistical values, which can be difficult to interpret and may be inappropriately used to assess reliability for questionnaires of different structure, length and type(Reference Trakman, Forsyth and Hoye63).

Strengths and limitations

We searched multiple databases as well as grey literature sources, allowing a comprehensive overview of the topic, and followed the Joanna Briggs best practice guidelines for scoping reviews.

However, this scoping review has limitations. Firstly, a number of potentially relevant articles were excluded because the full form of the NKAT was not available or not provided by the cited reference, within the paper or as supplementary material (i.e. only sample questions were available, or actual questions were not listed). Secondly, our search was limited to studies or NKATs in English language only. Thirdly, only tools that predominantly assessed general nutrition knowledge were included in this review. Tools that primarily focused on assessing other areas of nutrition-related areas (e.g. nutrition or health literacy, understanding of food labelling, nutrition attitudes, beliefs and behaviours) and knowledge on specific topics (e.g. heart disease or protein-energy malnutrition) were excluded. Finally, this review only focused on tools that collected quantitative responses (e.g. those that have a definitive correct answer). As knowledge is multidimensional, consideration of other data collection methods, such as focus groups and interviews, may also be required to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of nutrition knowledge.

Future directions and conclusion

This review has demonstrated that a variety of nutrition knowledge assessment tools developed for older adults and their carers exist for use within community- and institution-based settings. However, the majority of tools had unknown, or lacked, adequate validity or reliability. Therefore, nutrition knowledge scores should be interpreted with caution when administered to older adults or their carers. Further research is needed to validate existing or develop new nutrition knowledge assessment tools to ensure adequate validity and reliability, as well as to reflect current evidence, food trends and policies influencing nutrition knowledge. Development of tools to assess knowledge related to elderly nutrition is also needed for a range of healthcare professionals and informal caregivers providing care for older adults. Further research into these areas, including types of knowledge required(Reference Deroover, Bucher and Vandelanotte117) as well as behaviour change strategies, can guide evidence-based nutrition education programmes and public health campaigns to more effectively reduce the risk and burden of nutritional deficiencies and promote healthy ageing. In addition to general nutrition knowledge tools, specific tools to assess knowledge of risks for and treatment of protein-energy malnutrition may be needed. Ensuring adequate nutrition knowledge among older adults and their carers represents an important step towards improved quality of life and better health outcomes among the ageing population. This must not be overlooked, particularly in light of the recent coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic where consumption of a healthy diet is more important than ever for vulnerable population groups (including the elderly) as they are at the greatest risk of poor health outcomes and mortality(Reference Butler and Barrientos118).

Acknowledgements

The authors received no financial support for this work.

S.C., R.W.: primary authors, developed search strategy, and performed literature review, screening, data charting, data analysis and interpretation. F.O’L.: designed the study concept and experimental design, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. V.H.: provided advice on study design and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All included authors approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422421000330.