Rotating shift (RS) workers, whose work schedules change between day and night shifts, have higher risks of health problems, such as CVD, abnormal metabolism, obesity and depressive symptoms, than do workers who engage in fixed day shifts (DS) (i.e. DS workers)(Reference Boggild and Knutsson1–Reference Khosravipour, Khanlari and Khazaie6). However, the growth in the percentage of the population aged 65 years and older has increased the social demand for nurses and caregivers, many of whom work on a RS to provide care 24 h a day and 7 d a week in medical and care facilities.

RS work is associated with changes in habitual food consumption. Previous studies(Reference Tada, Kawano and Maeda7,Reference Yoshizaki, Tada and Kodama8) have demonstrated that RS workers consumed fewer potatoes and starches, green/yellow vegetables, white vegetables, fruits, algae, fish and shellfish, and meats than DS workers. In contrast, they consumed more confectioneries/savoury snacks, alcoholic beverages and sugar-sweetened beverages than DS workers. The available data support the close associations of habitual food consumption/diet quality with the risk of developing lifestyle-related diseases(Reference Bo, Musso and Beccuti9–Reference St-Onge, Ard and Baskin14). Thus, these changes in habitual food consumption may cause a higher risk of health problems in RS workers.

RS work is also associated with changes in dietary behaviour. For example, the percentage of individuals who habitually skipped breakfast on workdays was higher among RS workers than among DS workers(Reference Togo, Yoshizaki and Komatsu15). Breakfast skipping is a dietary behaviour that may increase the risk of obesity through a lower quality of overall food consumption (e.g. lower fibre intake, poorer nutrient intake and higher energy density)(Reference Timlin and Pereira16) and/or the misalignment between meal timing and the circadian clock(Reference Scheer, Hilton and Mantzoros17).

Considering the association between RS work, habitual dietary intake, obesity and breakfast skipping on workdays, it may be possible that breakfast skipping on workdays contributes to changes in dietary intake and increases in BMI in RS workers. However, the association of breakfast skipping on workdays, dietary intake and BMI in RS workers has not been examined. A deeper understanding of the relationship between breakfast skipping on workdays, dietary intake and BMI may assist in the development of strategies to improve diet quality and lifestyle-related diseases in RS workers, including worksite food environment improvements.

A previous study on nurses has indicated that the diurnal preference for activity timing (i.e. chronotype or morningness-eveningness) is associated with food consumption and that a later chronotype in RS workers compared with DS workers contributes to the differences in food consumption between RS workers and DS workers(Reference Yoshizaki, Komatsu and Tada18). A diurnal preference is also associated with dietary behaviour. A previous study of nurses has shown that a later chronotype is associated with abnormal temporal eating patterns (i.e. irregularity in the timing and a later meal timing), which is an obesity-related eating behaviour(Reference Yoshizaki, Kawano and Noguchi19). A study conducted with non-shift working adults with type 2 diabetes(Reference Reutrakul, Hood and Crowley20) has shown that a later chronotype is associated with more frequent breakfast skipping. Furthermore, a later chronotype has also been associated with a higher BMI in RS workers(Reference Yoshizaki, Komatsu and Tada18). Thus, chronotype could be a confounder between breakfast skipping, food consumption and BMI.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to elucidate the association between breakfast skipping on workdays and habitual dietary intake or BMI among RS workers. For this purpose, we evaluated differences in habitual dietary intake and BMI between RS breakfast-consumers, RS breakfast-skippers, and DS workers and examined the association after controlling for diurnal preference. Considering the possibility of the mediating effects of habitual dietary intake on the association between breakfast skipping and BMI, we further examined the association while controlling for total energy intake and food consumption. In addition, considering that the effect of RS work on habitual food consumption and breakfast skipping has been reported only in studies conducted with female workers, we examined the associations between breakfast skipping and habitual dietary intake or BMI in female RS workers(Reference Tada, Kawano and Maeda7,Reference Yoshizaki, Tada and Kodama8,Reference Togo, Yoshizaki and Komatsu15,Reference Pan, Schernhammer and Sun21,Reference Han, Choi-Kwon and Kim22) .

Subjects and methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional survey in 2010, in a population of nurses in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. Of the randomly selected nurses (n 5536, aged 20–59 years), a total of 3646 nurses (65·9 %) agreed to participate in the survey. Among these 3646 nurses, 1196 nurses were excluded from the analysis because of male sex (n 171), age < 20 years or > 59 years (n 128), missing data on sex (n 71), current work schedules (n 121), breakfast consumption habits (n 110), chronotype (n 261), and dietary intake (n 323), or BMI outliers (≥ 35·3 kg/m2) (n 11). Consequently, 2450 participants (1054 DS workers and 1396 RS workers) were analysed. More detail of this study has been shown in previous studies(Reference Togo, Yoshizaki and Komatsu5,Reference Tada, Kawano and Maeda7) .

Assessments

The questionnaire included habitual dietary intakes (Excel Eiyoukun)(Reference Takahashi, Yoshimura and Kaimoto23), breakfast consumption habits, diurnal preferences (a Japanese version of Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ))(Reference Ishihara, Saitoh and Inoue24) and demographic characteristics of the participants. Details of the questionnaire have been shown in previous studies(Reference Togo, Yoshizaki and Komatsu5,Reference Tada, Kawano and Maeda7) . The BMI were calculated from the self-reported heights and weights (weight/height2 (kg/m2)). For examining dietary compositions, the intake of each nutrient (i.e. protein, fat and carbohydrate) and food group consumption were adjusted by total energy intake using the residual method(Reference Willett25). Breakfast skipping was assessed by the response to the question, ‘How often did you usually have breakfast (a meal between 05.00 hours and 11.00 hours) on days of the DS?’ The participants were given a three-point Likert scale with responses defined as follows: (1) ‘Almost always (≥ 80 %)’; (2) ‘Sometimes (20 to < 80 %)’; and (3) ‘Almost never (< 20 %)’. The participants responded to the question by circling one of the given choices. A dichotomous variable was then created, where answers (1) were categorised as ‘consuming’ and answers (2) and (3) as ‘skipping’. Breakfast skipping on the start and end days of the evening/night shifts was also assessed in RS workers. For RS workers, we dichotomised the participants based on their responses to the three questions. We labelled those whose responses to all the three questions were ‘consuming’ as ‘RS workers who consumed breakfast (RS breakfast-consumers)’, and those whose responses to any of the three questions were ‘skipping’ as ‘RS workers who skipped breakfast (RS breakfast-skippers)’. We defined breakfast as a meal in the morning (between 05.00 hours and 11.00 hours) based on the previous results that all of the breakfast consumers of the DS and RS nurses had the first meal of the day of the DS between 05.30 hours and 08.30 hours(Reference Yoshizaki, Tada and Kodama8). The current paper focused only on workdays’ breakfast consumption/skipping due to the interest in the worksite environment.

Statistical analysis

To compare the differences in demographic characteristics and dietary habits between DS workers, RS breakfast-consumers and RS breakfast-skippers, a one-way ANOVA and the χ2 tests were used for the continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Post hoc analyses were performed using Tukey’s Student range tests for ANOVA. For categorical variables, residuals between the observed and expected frequencies were standardised to determine cells which were statistically different from the expected values.

To examine the differences of dietary habits and BMI in the RS breakfast-consumers and RS breakfast-skippers with those in DS workers, multivariable linear regressions were performed with dietary habits and BMI as the dependent variables, groups (dummy: DS workers (reference category) = (0, 0), RS breakfast-consumers = (1, 0), and RS breakfast-skippers = (0, 1)) as the independent variables, and the covariates (age, BMI at 20 years of age, years of experience as a nurse, years of experience as a RS worker, marital status, living alone, drinking habit(26), smoking habit(26), habitual sleep durations on nights between the DS and between days off, MEQ score, and physical activity level)(Reference Murase, Katsumura and Ueda27).

To examine the independent effects of breakfast skipping on the days of the DS and the evening/night shift on dietary habits in the RS workers, multivariable linear regressions were performed with dietary habits as the dependent variables; breakfast skipping on days of the DS, breakfast skipping on start days of the evening/night shift and breakfast skipping on end days of the evening/night shift as the independent variables (dummy: eating = 0 and skipping = 1); and the covariates (the number of evening/night shifts was also used as a covariate).

In the multivariable linear regressions, which were performed with BMI as a dependent variable, an extended model with the covariates was used: Model 1 = breakfast skipping on days of the DS, breakfast skipping on start days of the evening/night shift, and breakfast skipping on end days of the evening/night shift as the independent variables, and the covariates (the number of evening/night shifts was also used as a covariate); Model 2 = Model 1 plus total energy intake and food consumption. Regarding the missing data in the covariates, since Little’s χ 2 test suggested that the missing data were missing completely at random, multivariable analyses were performed using the data set of subjects without missing data (i.e. complete-case data set) (n 2216). P values less than 0·05 using two-tailed tests were considered statistically significant. The corrections for multiple tests in the multivariable linear regressions for dietary habits were performed using the adaptive Benjamini–Hochberg procedure(Reference Benjamini and Hochberg28). The procedure controlled for the false discovery rate (FDR) using a sequential modified Bonferroni correction for multiple hypothesis testing. The initial FDR threshold was 0·05. All the statistical analyses were performed with a STATA MP 16 (Stata Corporation).

Results

The demographic characteristics of the DS workers, RS breakfast-consumers and RS breakfast-skippers are shown in Table 1. Age, years of experience as a nurse, years of experience as a RS worker, habitual sleep duration on nights between the DS, habitual sleep duration on nights between days off, MEQ score and the frequency of breakfast skipping were significantly (P < 0·05) different between the groups. The BMI was significantly (P < 0·05) higher in both the RS breakfast-skippers and RS breakfast-consumers compared with the DS workers. The BMI at 20 years of age was significantly (P < 0·05) higher in the RS breakfast-skippers than in the DS workers. The percentage of individuals who were married, living alone, habitual drinkers and habitual smokers among the RS workers were also significantly (P < 0·05) different compared with the other groups or with only the DS workers. The physical activity level did not differ (P > 0·05) between the groups.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the participants

DS, day shift; RS, rotating shift; MEQ, Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire.

* ANOVA.

† χ2 test.

‡ Adjusted residuals greater than 1·96.

§ Adjusted residuals less than –1·96.

The energy-adjusted habitual nutrient intakes and food consumption of the DS workers, RS breakfast-consumers and RS breakfast-skippers are also shown in Table 2. Consumption of potatoes and starches, green/yellow vegetables, white vegetables, fruits, algae, fish and shellfish, confectioneries/savoury snacks, alcoholic beverages, and sugar-sweetened beverages were significantly (P < 0·05) different between the DS workers and RS breakfast-skippers. In contrast, consumption of these did not differ between the DS workers and RS breakfast-consumers. The total energy intake was significantly (P < 0·05) higher in the RS breakfast-consumers than in the DS workers, but lower in the RS breakfast-skippers compared with the DS workers. Protein intake was significantly (P < 0·05) lower in the RS breakfast-skippers compared with the DS workers and RS breakfast-consumers.

Table 2 Habitual dietary intakes of the participants

DS, day shift; RS, rotating shift.

* Adjusted by total energy intake using the residual method.

† ANOVA.

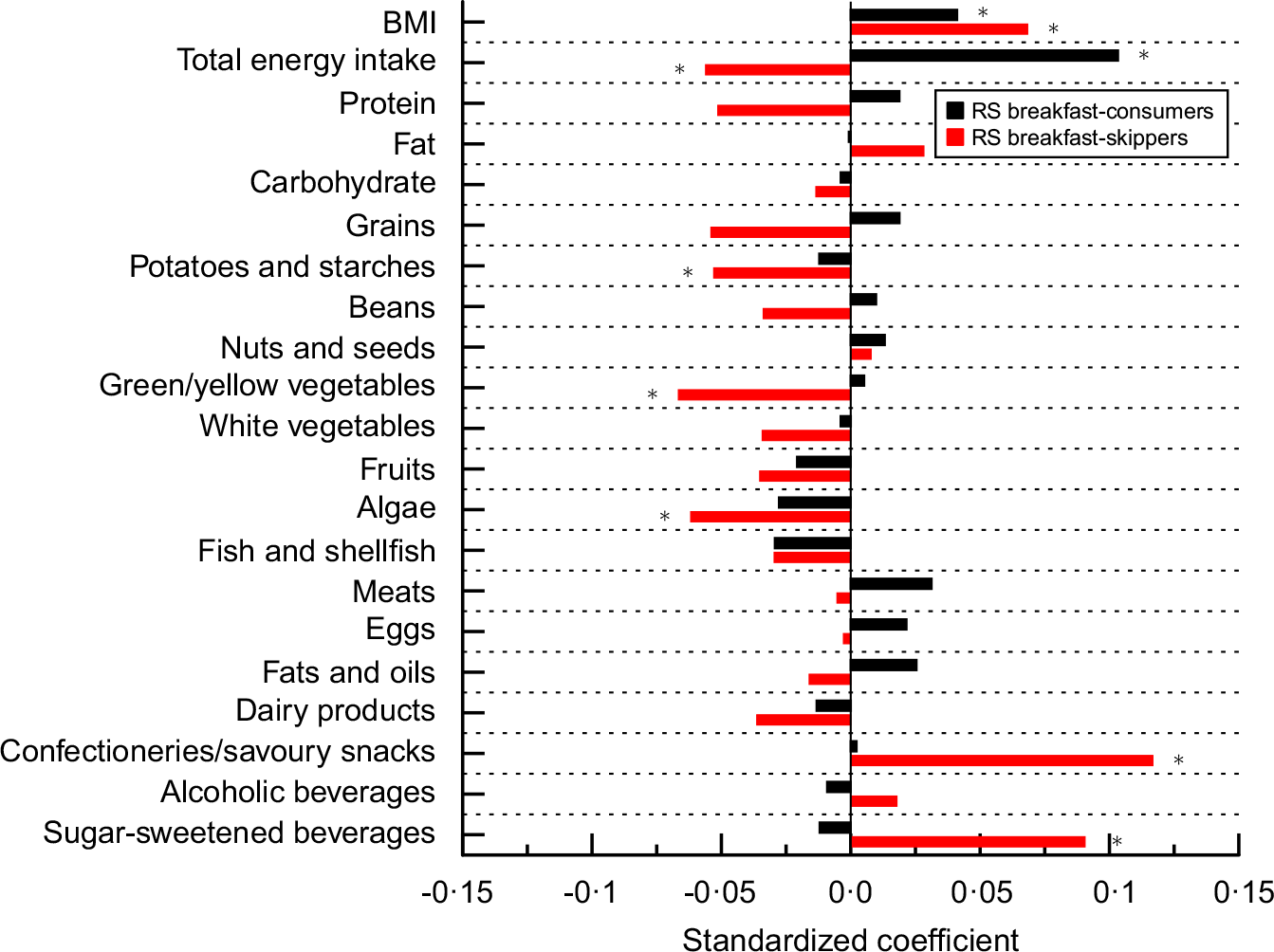

The BMI, energy-adjusted habitual nutrient intakes, and food consumption in the RS breakfast-consumers and RS breakfast-skippers relative to those in the DS workers in the multivariable linear regressions are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1. In the RS breakfast-skippers, the total energy intake and consumption of potatoes and starches, green/yellow vegetables, and algae were significantly (P < 0·05) lower than that of the DS workers. In contrast, the consumption of confectioneries/savoury snacks and sugar-sweetened beverages was significantly (P < 0·05) higher in the RS breakfast-skippers than that of the DS workers. The BMI was significantly (P < 0·05) higher in the RS breakfast-skippers than in the DS workers. In the RS breakfast-consumers, the total energy intake was significantly higher (P < 0·05) than in the DS workers. In contrast, the energy-adjusted habitual nutrient intakes and consumption of all the food groups were not different (P > 0·05) from those of the DS workers. The BMI was significantly (P < 0·05) higher in the RS breakfast-consumers compared with the DS workers. These results did not change when the reference group was changed from DS workers to DS breakfast-consumers, whose response to the question on the days of the DS was ‘consuming,’ (n 804), except for potatoes and starches (P = 0·073) (online Supplementary Table S1).

Table 3 BMI and habitual dietary intakes in rotating shift (RS) breakfast-consumers and RS breakfast-skippers relative to day shift (DS) workers in multivariable linear model analysis

MEQ, Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire; B, unstandardised coefficient.

Adjusted by age, BMI at 20 years of age, years of experience as a nurse, years of experience as a RS worker, marital status, resident status, drinking habit, smoking habit, habitual sleep durations on nights between DS and between days off, physical activity level, and MEQ score.

Fig. 1 Standardised coefficients of rotating shift (RS) workers who consumed breakfast (RS breakfast-consumers) and RS workers who skipped breakfast (RS breakfast-skippers) on BMI and habitual dietary intakes in multivariable linear regression. Adjusted by age, BMI at 20 years of age, years of experience as a nurse, years of experience as a RS worker, marital status, resident status, drinking habit, smoking habit, habitual sleep durations on nights between day shifts (DS) and between days off, physical activity level, and Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) score. *P < 0·05. Reference group = DS workers.

In the RS workers, the association of breakfast skipping on the days of the DS, start days of the evening/night shift and end days of the evening/night shift with dietary intakes are shown in Table 4. Multivariable linear regression showed that breakfast skipping on the days of the DS and end days of the evening/night shift were independently and significantly (P < 0·05) associated with a lower total energy intake and higher consumption of confectioneries/savoury snacks and sugar-sweetened beverages. These associations survived the FDR correction except for breakfast skipping on the end days of the evening/night shift for consumption of confectioneries/savoury snacks and sugar-sweetened beverages. Breakfast skipping on the days of the DS was also significantly (P < 0·05) associated with a higher fat intake, lower carbohydrate intake, and a lower consumption of grains and white vegetables. These associations survived the FDR correction except for white vegetables. Breakfast skipping on the end days of the evening/night shift was significantly P < 0·05) associated with a lower consumption of fats and oils.

Table 4 Coefficients of breakfast skipping on days of the day shift (DS), start days of the evening/night shift and end days of the evening/night shift on habitual dietary intakes in rotating shift (RS) workers in multivariable linear model analysis

MEQ, Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire; FDR, false discovery rate; B, unstandardised coefficient.

Adjusted by age, BMI at 20 years of age, years of experience as a nurse, years of experience as a rotating shift worker, the number of evening/night shifts, marital status, resident status, drinking habit, smoking habit, habitual sleep durations on nights between day shifts and between days off, physical activity level, and MEQ score.

* P < 0·05 after FDR corrections.

The associations between breakfast skipping and BMI are shown in Table 5. In Model 1, breakfast skipping on the days of the DS was associated with a higher BMI, at a trend level (P < 0·10) (Table 5). In Model 2, breakfast skipping on the days of the DS was positively and significantly (P < 0·05) associated with BMI (Table 5), whereas the total energy intake was significantly (P < 0·05) associated with BMI (online Supplementary Table S2).

Table 5 Coefficients of breakfast skipping on BMI in rotating shift (RS) workers in multivariable linear model analysis

β, standardised coefficient; MEQ, Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire; DS, day shift.

* Adjusted by age, BMI at 20 years of age, years of experience as a nurse, years of experience as a rotating shift worker, the number of evening/night shifts, marital status, resident status, drinking habit, smoking habit, habitual sleep durations on nights between day shifts and between days off, physical activity level, and MEQ score.

† Adjusted by variables in Model 1, total energy intake and food group consumption.

Discussion

The results showed that RS breakfast-skippers had a lower total energy intake, lower diet quality and higher BMI than DS workers. The RS breakfast-consumers had a higher total energy intake and higher BMI than the DS workers. In the RS workers, breakfast skipping on the days of the DS and end days of the evening/night shift was associated with a lower total energy intake and lower diet quality (i.e. a lower carbohydrate intake; higher fat intake; lower consumption of grains, white vegetables, and fats and oils; higher consumption of confectioneries/savoury snacks and/or sugar-sweetened beverages). Breakfast skipping on the days of the DS was positively and significantly associated with BMI in the RS workers, while controlling for total energy intake and food consumption. The results suggest that breakfast skipping on workdays may contribute to a difference in the dietary intake and BMI between the RS workers and DS workers and may increase BMI in the RS workers, independent of dietary intake.

Consumption of potatoes and starches, green/yellow vegetables, algae, confectioneries/savoury snacks, and sugar-sweetened beverages was different between the RS breakfast-skippers and the DS workers (Fig. 1, Table 3). Among these, the consumption of confectioneries/savoury snacks and sugar-sweetened beverages was associated with breakfast skipping on the days of the DS (Table 4). The consumption was also associated with breakfast skipping on the end days of the evening/night shift before the FDR correction (Table 4). These results indicate that some of the previously reported differences in dietary consumption between the RS workers and DS workers(Reference Tada, Kawano and Maeda7,Reference Peplonska, Kaluzny and Trafalska29–Reference Hemio, Puttonen and Viitasalo31) may have been caused by breakfast skipping on workdays in the RS workers. The consumption of green/yellow vegetables and algae was not significantly associated with breakfast skipping on any of the days of the shifts (Table 4). However, all the coefficients of breakfast skipping had negative values for the green/yellow vegetables (Table 4), indicating that each negative effect of breakfast skipping on the days of the DS, start days of the evening/night shift and end days of the evening/night shift may have contributed to the significantly lower consumption of green/yellow vegetables in the RS breakfast-skippers than in the DS workers (Table 2).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that breakfast skipping on workdays may be associated with habitual dietary intake and BMI in RS workers. Additionally, our results showed that breakfast skipping on workdays may be associated with a higher BMI in the RS workers, independent of dietary intakes (Table 5). Considering that breakfast skipping was associated with a lower total energy intake (Table 4), which, in turn, was associated with a lower BMI (online Supplementary Table S2), the entire effect of breakfast skipping on BMI may have been smaller than the independent effect (Table 5). These results are supported by previous findings in adults, including non-RS workers. For example, a previous study conducted with US adults(Reference Zeballos and Todd32) has shown that breakfast skipping was associated with a lower energy intake and low quality of diet. Another study using data from a National Nutrition Survey in Japan demonstrated that breakfast skipping was associated with low quality of diet in adults aged 18–49 years(Reference Murakami, Livingstone and Fujiwara33). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that the timing of the meal intake (i.e. breakfast skipping, a later dinner time or higher energy intake at dinner) contributed to increases in BMI and obesity(Reference Bo, Musso and Beccuti9,Reference Ma, Bertone and Stanek34) , after statistically controlling for total energy intake in individuals not engaged in night shift work. One of the possible mechanisms underlying this association may have been the decrease in insulin sensitivity later in the day(Reference Van Cauter, Désir and Decoster35).

Habitual nutrient intake and food consumption between the RS breakfast-consumers and DS workers or DS breakfast-consumers did not differ. Considering that the percentages of breakfast consumers of the RS workers were not high (i.e. 62·8 % and 59·0 % on the days of DS and end days of the night shift, respectively), interventions for increasing the frequency of breakfast consumption on these days, including improvements in the worksite food environment in the morning, may be a population strategy for improving diet quality and BMI in the RS breakfast-skippers. However, it should be noted that previous intervention studies have indicated that eating breakfast increased total energy intake and weight(Reference Sievert, Hussain and Page36,Reference LeCheminant, LeCheminant and Tucker37) . Our results also showed that the total energy intake and BMI were both higher in the RS breakfast-consumers than in the DS workers (Table 3) or DS breakfast-consumers (online Supplementary Table S1) and that the total energy intake was positively associated with BMI in the RS workers (online Supplementary Table S2). Future studies should carefully examine the effects of interventions for breakfast consumption, including not only the diet quality, but also the total energy intake and BMI in the RS breakfast-skippers.

Previous animal and human studies have shown that changing meal timing can shift the phase of the circadian clock(Reference Mendoza, Graff and Dardente38–Reference Wehrens, Christou and Isherwood40). Additionally, a previous study(Reference Yoshizaki, Kawano and Tada41) indicated that the phase angle of a 24-h rhythm in the cardiac autonomic nervous system activity was delayed among RS workers compared with DS workers on the days of the DS, whereas the sleep–wake cycle was not. Given that the misalignment between the sleep–wake cycle and the circadian rhythm causes physical/mental problems(Reference Scheer, Hilton and Mantzoros17,Reference Nguyen and Wright42,Reference Leproult, Holmback and Van Cauter43) , interventions for having breakfast in the RS breakfast-skippers may also be effective for preventing physical/mental problems via the improvement of the misalignment on the days of the DS. Therefore, the effects of the interventions on the phases of the circadian clock, as well as on diet quality, total energy intake and BMI, should be carefully examined.

Although the underlying physiological mechanisms in the association of breakfast skipping with habitual nutrient intake and food consumption are unclear, previous studies have shown several possibilities. For example, a 7-d intervention study in healthy and normal-weight adults(Reference Gwin and Leidy44) found that breakfast skipping increased the level of plasma ghrelin and activation in the brain area associated with a food reward. Other studies have indicated that consumption of food with high added sugar may displace the consumption of more nutrient-dense food(Reference Murphy and Johnson45–Reference Deshmukh-Taskar, Radcliffe and Liu47). This may explain the relationship between breakfast skipping and the higher consumption of confectioneries/savoury snacks and sugar-sweetened beverages and lower consumption of grains, green/yellow vegetables, and algae in the RS workers in the current study results.

We acknowledge the following limitations in this study. First, the current samples consisted of only Japanese female nurses. The generalisation of our results to the general RS workers may have been limited. Second, variables such as breakfast skipping, habitual dietary intake and BMI were self-reported. However, a previous study has reported that BMI computed from self-reported weight and height is well validated(Reference Hodge, Shah and McCullough48). Third, due to the lack of any standard definition of breakfast, we defined breakfast as a meal in the morning (between 05.00 and 11.00) based on the results that all breakfast consumers of the DS and the RS nurses in the previous study had the first meal of the day of the DS between 05.30 and 08.30(Reference Yoshizaki, Tada and Kodama8). To compare the association between breakfast skipping and habitual dietary intake among different samples, a standardised definition of breakfast may be needed. Finally, this cross-sectional study could not establish the cause-and-effect relationship between breakfast skipping, habitual dietary intake and BMI. Longitudinal studies or interventional studies are required to test whether breakfast skipping affects habitual dietary intake and BMI in RS workers.

In conclusion, breakfast skipping on workdays may contribute to a difference in the dietary intake and BMI between RS workers and DS workers and may increase BMI in RS workers, independent of dietary intake. These findings have important implications for the development of novel strategies to improve the worksite food environment for the prevention of poor health caused by habitual dietary intakes in RS workers.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We thank Toshiko Hirasawa, who was the President of the Kanagawa Nursing Association at the time that data for this study were collected, and all the individuals who participated in this study. Authorship: T.Y., Y.T., T.K. and F.T. conceptualised the study; T.Y. and F.T. analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors played an important role in interpreting the results, provided substantive feedback on the manuscript and approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, Japan (Approval Number: H22027). Informed consent was obtained from all participants by making it clear that proceeding to the survey after reading the information sheet on the front page of the anonymous questionnaire and submitting their results was indicative of informed consent.

Financial support:

This study was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists 20K19720, Research Activity Start-up 20800085, Scientific Research (C) 22500690, Challenging Exploratory Research 15K12693, Scientific Research (B) 15H03094).

Conflict of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980023000794