Introduction

African Americans have higher rates of obesity, food insecurity and poverty compared with white residents of the United States.(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory1–Reference Semega, Kollar and Creamer3) Public health professionals and nutrition educators have acknowledged the need to address institutional factors and structural racism that contribute to biases toward and health inequities among Americans of colour, although prior research related to racism has largely examined interpersonal discrimination.(Reference Bailey, Krieger and Agénor4,Reference Gee and Ford5) One common definition of structural racism is ‘the totality of ways in which societies foster discrimination, via mutually reinforcing [inequitable] systems like in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and criminal justice, that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources.’(Reference Krieger6) The disproportionate impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on both the health and economic livelihood of Americans of colour has brought renewed attention to the influence of structural racism on health.(Reference Singleton, Uy and Landry7,8) These overlapping systems of discrimination have contributed to the difference in food insecurity rates between African Americans and white residents of the United States and restricted African Americans’ ability to make healthful food choices.(Reference Barker, Francois and Goodman9,Reference Odoms-Young10)

Nutrition education has the potential to alleviate some of these stresses, when paired with macro-system changes. Such education may provide African American participants with knowledge to help overcome barriers imposed by structural racism. For example, a recent review of participation outcomes in the SNAP-Ed programme found a beneficial effect on food insecurity, which is disproportionately experienced by African Americans compared with white Americans.(Reference Rivera, Maulding and Eicher-Miller11) However, nutrition education alone is not enough to change behaviour in the face of institutional barriers to healthy eating.(Reference Mancino and Kinsey12) Several studies have identified an increased density of fast food restaurants, areas termed ‘food swamps’, in majority African American neighbourhoods,(Reference Hager, Black and Cockerham13–Reference Sanchez-Vaznaugh, Weverka and Matsuzaki15) a contributing factor to racial disparities in obesity rates.(Reference Cooksey-Stowers, Schwartz and Brownell16,Reference Cooksey Stowers, Jiang and Atoloye17) Nutrition educators and public health professionals must therefore also encourage broader policy, systems and environmental (PSE) changes to address and work towards dismantling these barriers. These PSE change interventions promote healthy eating and increased physical activity according to the social-ecological model of behaviour change, acknowledging influences on health behaviours beyond individual-level knowledge and motivation.(Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien18) These types of changes, especially when paired with education, could play an important role in addressing barriers to healthful eating imposed on African Americans.

A framework titled the ‘Equity-Oriented Obesity Prevention Framework’ provides a basis from which to address structural barriers faced by marginalised populations through nutrition education and nutrition-focused PSE changes.(Reference Kumanyika19) The framework uses a health equity lens and acknowledges influences beyond the primary pathway to obesity, including four groups of interventions to address obesity in marginalised populations: Increase Healthy Options, Reduce Deterrents, Improve Social and Economic Resources, and Build on Community Capacity. Interventions to increase healthy options include improving locations and marketing practices of supermarkets and improving standards for food provision in schools and worksites. Reducing deterrents to health behaviours could include decreasing targeted marketing of unhealthy foods and making unhealthy foods less affordable. The framework describes interventions to improve social and economic resources as strategies to increase food purchasing power, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).(Reference Kumanyika19) Finally, interventions described as building on community capacity include increasing community members’ voice in decision-making and increasing awareness of and demand for more healthful food through educational efforts to increase food and nutrition literacy and promote behaviour change. Despite the potential applications of this framework and its proposed interventions to address structural racism through nutrition-focused PSE changes and nutrition education, little published literature has directly related the framework to nutrition education or nutrition-focused PSE change interventions targeted to African Americans.

Additionally, there is also a lack of literature reviews which have examined interventions addressing the impacts of structural racism in the food environment among African Americans. Previous reviews have examined nutrition education and weight loss interventions tailored to African American populations,(Reference Fitzgibbon, Tussing-Humphreys and Porter20–Reference Di Noia, Furst and Park23) but these reviews have focused only on educational interventions alone, rather than interventions addressing structural barriers to healthy eating. Another review examined the built environment and its association with health behaviours among African Americans, but did not review interventions to improve it.(Reference Casagrande, Whitt-Glover and Lancaster24)

The primary aim of this scoping review is therefore to summarise the available literature and identify gaps in the knowledge base regarding nutrition education and PSE interventions designed for African Americans to address structural barriers to healthful eating patterns.

Methods

This review proceeded according to guidance for scoping reviews provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute.(Reference Peters, Godfrey and McInerney25) Findings are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR).(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin26) The protocol was registered a priori at Open Science Framework (osf.io/taj5c/).(Reference Greene, Houghtaling and De Marco27) The scoping review was guided by this research question: What nutrition education or nutrition-focused PSE change interventions have been conducted in an attempt to address structural racism faced by African Americans?

Search strategy

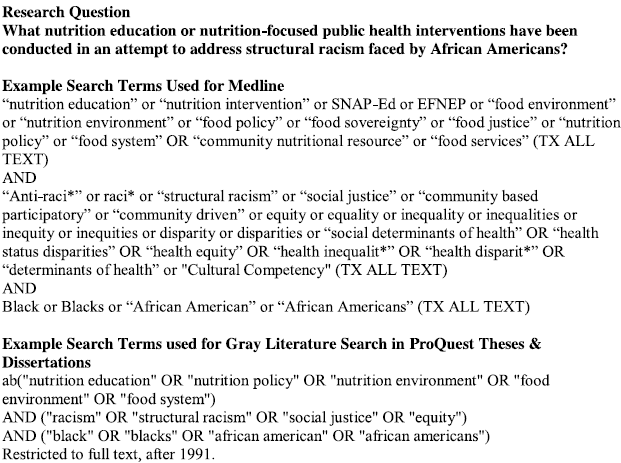

This scoping review began with an exploratory search of EBSCOhost’s Agricola, ERIC, SocINDEX and Psychinfo to ensure no scoping or systematic reviews had been published on this topic. Following our initial exploration, we developed our search strategy in partnership with a research librarian (R.L.M.). The review protocol was registered 31 October 2020 at Open Science Framework, and the search was performed in November 2020. Searches were repeated in May 2021 to identify any additional sources published since the November 2020 search. The EBSCOhost Medline database was added to the planned search strategy following the initial search and consultation with R.L.M. The inclusion of databases from diverse subject areas reflects the complexity and interdisciplinary nature of this investigation. On 8 August 2020, following the initial search, we developed an exhaustive search strategy for the terms which were used in the scoping review protocol. The search terms were also translated into the appropriate subject terms used in the four different peer-reviewed literature databases, Agricola, ERIC, SocINDEX, Psychinfo and Medline. An example of the search for each question is available in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Search strategies for the scoping review of nutrition interventions addressing structural racism among African Americans.

The review of grey literature consisted of a search of the ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database, websites and online resources pertaining to nutrition education provided the Cooperative Extension Service, such as the Association of Family and Consumer Science agents (neafcs.org) and the Regional Nutrition Education and Obesity Prevention Centers of Excellence (psechange.org) using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. Separate search terms were used for the grey literature search to narrow results to those most relevant to the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The reference lists of identified reports and articles were searched for additional sources, and the reference lists of additional articles identified in this manner were also searched for additional sources.

Eligibility criteria

Our research question and inclusion criteria were guided by the PCC (population, concept, context) mnemonic recommended by the JBI Reviewer’s Manual for Scoping Reviews.(Reference Peters, Godfrey and McInerney25) Studies were included only if the populations were majority (>50 %) African American and conducted in the context of the United States in the English language. This investigation is focused exclusively on African Americans in the United States because of their unique historical experience of enslavement, Jim Crow discrimination and the current discriminatory effects of ostensibly colour-blind policies in the food environment in the United States.(Reference Bailey, Krieger and Agénor4) We included studies conducted both with adults and with children to identify as many as articles as possible. The concept portion of our research question aimed to include publications detailing nutrition-focused interventions conducted specifically to the benefit of African Americans, including nutrition education and nutrition-focused PSE changes.

Only studies published between 1991 and the search date were included. This date was selected based on the 1991 ‘Pathway to Diversity’ document released by the Extension Committee on Organization and Policy (ECOP) which focused Cooperative Extension Service efforts on increasing diversity in staff and including more minority audiences in educational programming.(Reference Fowler and Johnsrud28) The Cooperative Extension Service operates through Land Grant Universities in the United States and implements federally funded nutrition education programmes such as SNAP-Ed. This document signalled a shift in the delivery of services by an organisation with a large reach which implements nutrition education and PSE interventions.

Data extraction and evidence mapping

Searches were conducted according to the strategy outlined above. The grey literature search was conducted by the first author (M.G.). All search results were exported to Zotero software and saved. Duplicates were removed, and the results were then exported to Excel (Office 365, v16·0; Microsoft Inc. Redmond, Washington). M.G. and D.H independently reviewed titles and abstracts, then independently reviewed articles for inclusion. Any disagreement regarding which articles to include was resolved through consensus or a third reviewer (B.H.) if needed.

Standardised data extraction tools were designed by M.G. using Excel to address the relevant data for each research question. Descriptive information extracted from all articles included authors, publication year, study design, study objectives, setting, population and an intervention description. Additional information extracted from articles included how the intervention addressed structural barriers to healthy eating among African Americans, evaluation design and evaluation results. Intervention descriptions from all articles were compared with constructs of the Equity-Oriented Obesity Prevention Framework proposed by Kumanyika to determine which constructs were targeted.(Reference Kumanyika19)

M.G. extracted data from all articles and distributed an equal number of articles selected for inclusion to B.H., D.B., M.D. and C.S. for data extraction, such that data were extracted from all articles by the first author and one co-author. Any disagreement in data extraction was resolved through consensus, and by a third reviewer (D.H.) if necessary.

Results

The literature search resulted in 1513 title and abstract records pertaining to our review question (Fig. 2). Titles and abstracts were largely excluded from full text review because they were not conducted in the United States, were not conducted in a majority African American population or described an observational study in which authors did not conduct an intervention. Of the 101 full-text articles screened, 30 articles met the inclusion criteria.(Reference Trude, Surkan and Cheskin29–Reference Suarez-Balcazar, Hellwig and Kouba47,Reference Suarez-Balcazar, Hellwig and Kouba47–Reference Locher, Waselewski and Sonneville58) Of the full-text articles that were excluded, the majority (54 %) were rejected because the interventions studied did not directly address structural or institutional barriers to healthy eating in African Americans’ food environments. Following our initial search which resulted in twenty-four articles, an additional five articles were identified through searching of reference lists,(Reference Wilcox, Parrott and Baruth53–Reference Baker, Motton and Seiler57) and one additional article was identified in the repeated search in May 2021.(Reference Locher, Waselewski and Sonneville58) The article included in the repeated search was published in May 2020 and detailed a meal delivery programme designed to supplement WIC among African American mothers in Michigan.(Reference Locher, Waselewski and Sonneville58)

Fig. 2. PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Of the thirty articles which met our inclusion criteria (Table 1), most were conducted in urban settings (n = 21, 70 %), and a small number were conducted in rural settings (n = 5, 17 %) or conducted interventions that covered both settings or were not classified as rural or urban (n = 4, 13 %). The majority of included studies were conducted to benefit adults (n = 18, 60 %), and a smaller number benefitted children (n = 6, 20 %) or both adults and children (n = 6, 20 %). Nearly all sources included in the review (n = 28, 93 %) were peer-reviewed journal articles, though a small number (n = 2, 7 %) were doctoral dissertations or master’s theses. No results from the search of web pages met the inclusion criteria.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of studies detailing nutrition-focused interventions that address structural barriers in African Americans’ food environments (n = 35)

Many interventions described in the included studies consisted of nutrition education in combination with a PSE intervention (n = 12, 40 %) (Table 2). For example, Trude et al. led two studies (2018 and 2019) which evaluated the effect of a multicomponent intervention to increase access to and promotion of healthier foods in corner stores in African American neighbourhoods which also included nutrition education.(Reference Trude, Surkan and Cheskin29,Reference Trude, Anderson Steeves and Gittelsohn44) Campbell (1999), Allicock (2012), Baruth (2013) and Wang (2013) implemented church-based interventions which provided nutrition education and also changed church environments to support healthy eating.(Reference Allicock, Campbell and Valle37–Reference Wang, Lee and Hart39,Reference Campbell, Demark-Wahnefried and Symons51) Other articles described combined environmental and systems interventions (n = 7, 23 %), such as changes to stocking habits and the retail environment in corner stores,(Reference Gittelsohn, Song and Suratkar30) or the addition of a community garden at a medical clinic which also provided produce to patients and local community members.(Reference Milliron, Vitolins and Gamble49) Articles including environmental interventions alone (n = 4, 13 %) included diverse strategies, such as the placement of new grocery stores, community gardens and calorie information in retail settings.(Reference Bleich, Herring and Flagg40) Three studies (10 %) consisted of direct education alone, which empowered and taught African Americans to advocate for healthy options in their community,(Reference Backman, Scruggs and Atiedu48,Reference Conlon, Kahan and Martinez55) or taught participants about racially targeted junk food advertisements.(Reference Isselmann DiSantis, Kumanyika and Carter-Edwards41) Two studies which examined policy interventions alone (7 %) focused on changes to WIC package revisions and how they affected availability of healthy food in stores.(Reference Cobb, Anderson and Appel31,Reference Hillier, McLaughlin and Cannuscio46) One study (3 %) examined a combined policy and system intervention to provide Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program (FMNP) coupons,(Reference Stallings, Gazmararian and Goodman43) and one study examined a systems intervention alone, which provided biweekly grocery deliveries to low-income pregnant women.(Reference Locher, Waselewski and Sonneville58)

Table 2. Details of sources describing nutrition-focused interventions addressing structural barriers to healthy eating in African Americans’ food environments

Interventions addressed structural racism in African Americans’ food environment through interventions targeted to retail settings and/or corner stores (n = 7, 23 %), farmers’ markets and/or produce distribution (n = 7, 23 %), community gardens (n = 5, 17 %), church settings (n = 5, 17 %), school and/or early care settings (n = 3, 10 %), or consisted of direct education alone (n = 4, 13 %). Several studies targeted more than one of these settings simultaneously. One such example is the Chicago Food System Collaborative, which worked to add a farmers’ market to a low-income African American neighbourhood, change the types of food offered in neighbourhood schools and add salad bars to ten of those schools.(Reference Suarez-Balcazar, Hellwig and Kouba47)

Evaluation designs of the included articles were majority quasi-experimental pre-test–post-test designs (n = 16, 53 %). Other designs included qualitative methods alone (n = 5, 17 %), randomised controlled trials (n = 4, 13 %), post-only measures (n = 2, 7 %) and process evaluations alone (n = 3, 10 %). All five of the articles using qualitative methods alone evaluated perceptions of systems and/or environmental changes, four of which related to farmers’ markets and/or produce distribution efforts. Among the twenty-two articles which used quantitative evaluation methods, twenty found some positive evaluation result and two did not find any impact of the studied intervention. Notable intervention outcomes included weight loss or decreased BMI or BMI Z-score,(Reference Barnidge, Baker and Schootman42,Reference Ard, Carson and Shikany50,Reference Choudhry, McClinton-Powell and Solomon52) increased fruit and/or vegetable consumption,(Reference Stallings, Gazmararian and Goodman43,Reference Campbell, Demark-Wahnefried and Symons51,Reference Wilcox, Parrott and Baruth53,Reference Baker, Motton and Seiler57) and changes in purchasing behaviours.(Reference Trude, Surkan and Cheskin29,Reference Bleich, Herring and Flagg40)

Comparison of results to the ‘Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention’ framework

Of the thirty included articles which studied interventions addressing structural racism in African Americans’ food environments, many targeted more than one aspect of the Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention Framework (Table 3). Nearly all (n = 25, 83 %) targeted the ‘Increase Healthy Options’ construct of the framework, largely by providing additional sources of fresh fruits and vegetables in African American communities. These types of interventions included things like the addition of new community gardens(Reference Barnidge, Baker and Schootman42,Reference Milliron, Vitolins and Gamble49,Reference Grier, Bennette and Covington54,Reference Baker, Motton and Seiler57) or farmers’ markets,(Reference Alkon and Norgaard32,Reference Suarez-Balcazar, Hellwig and Kouba47,Reference Cyzman, Wierenga and Sielawa56) or including more fresh produce in existing retail environments.(Reference Trude, Surkan and Cheskin29–Reference Cobb, Anderson and Appel31,Reference Trude, Anderson Steeves and Gittelsohn44,Reference Hillier, McLaughlin and Cannuscio46) A majority of the included articles (n = 18, 60 %) targeted the ‘Build on Community Capacity’ construct, mostly through nutrition education to provide behaviour change knowledge and skills and promote healthier behaviours. A small number of studies targeted the ‘Improve Social and Economic Resources’ (n = 2, 7 %) and the ‘Reduce Deterrents’ (n = 2, 7 %) constructs. Those studies targeting ‘Improve Social and Economic Resources’ described interventions which provided additional funding for food targeted to African American families, through additional funds to be spent at farmers’ markets,(Reference Stallings, Gazmararian and Goodman43) or funds to be spent on grocery delivery services.(Reference Locher, Waselewski and Sonneville58) Studies targeting ‘Reduce Deterrents’ included an intervention to make consumers aware of marketing tactics used by vendors of unhealthy food to target African Americans,(Reference Isselmann DiSantis, Kumanyika and Carter-Edwards41) and an intervention to make consumers aware of the calorie content of sugar-sweetened beverages.(Reference Bleich, Herring and Flagg40)

Table 3. Comparison of included study interventions to interventions suggested by the ‘Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention’ framework

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to identify and describe the available literature describing nutrition interventions that address structural racism in the food environment that impacts African Americans. This review is the first to describe available literature regarding nutrition interventions which specifically addressed structural barriers to healthy eating in this population. Despite the recent recognition of structural racism as a threat to public health and food security among African Americans,(Reference Singleton, Uy and Landry7,8) none of the studies meeting our inclusion criteria specifically named structural racism as a factor in the development or implementation in the studied interventions. This finding underscores the need for academic institutions and public health nutrition practitioners to acknowledge and address structural racism affecting African Americans through nutrition education and PSE change interventions.

The ‘Equity-Oriented Obesity Prevention Framework’ provides a basis from which to refocus nutrition interventions and PSE changes to address health equity issues and the impact of structural racism on marginalised populations.(Reference Kumanyika19) Many studies included in this review addressed the ‘Increase Healthy Options’ and ‘Build on Community Capacity’ constructs of this framework, by providing additional fresh produce in African Americans’ communities and direct nutrition education programmes targeted to African Americans, respectively. Though these strategies may be well intentioned, charity-focused strategies such as these are not adequate to address structural barriers to healthy eating.(Reference Wicks, Trevena and Quine59) Further, nutrition education programmes that focus on individual responsibility in the context of these barriers may be seen as patronising and unhelpful.(Reference Kolavalli60) This may be related to an ideology of ‘cultural racism’ described by the sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva which asserts that the standing of marginalised populations in society is due to a cultural deficit in those populations.(Reference Bonilla-Silva61) In public health practice and research, this ideology manifests itself as a ‘lifestyle hypothesis’ in which marginalised populations are blamed for health disparities owing to supposed lack of knowledge and flawed decision-making.(Reference Bassett and Graves62) Charity-focused strategies to educate and provide additional healthy options to marginalised populations may be perpetuating these ideologies if they do not acknowledge and address structural racism. To best support health equity, it will be vital to implement strategies featured in other portions of the Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention framework alongside those focused on increasing healthy options and providing education.

Unfortunately, our results found very few studies which addressed the ‘Reduce Deterrents’ and ‘Improve Social and Economic Resources’ constructs of the framework, strategies which might better address disparities in nutritional status and structural racism experienced by African Americans. Several ways in which structural racism manifests in the food environment, such as an increased prevalence of unhealthy food outlets (‘food swamps’) in African American neighbourhoods and targeted marketing of unhealthy foods to African Americans,(Reference Cooksey-Stowers, Schwartz and Brownell16,Reference Cooksey Stowers, Jiang and Atoloye17,Reference Grier and Kumanyika63–Reference Nguyen, Glantz and Palmer65) cannot be addressed by increasing healthy options alone. The most robust strategies to address structural racism would address the ‘Improve Social and Economic Resources’ aspect of the framework, because racial health disparities will persist as long as there are disparities in socioeconomic status. Sociologists have argued that socioeconomic status is a ‘fundamental cause’ of health disparities, because as new treatments and methods of disease prevention arise, they will be available to those with the economic resources to take advantage of them.(Reference Link and Phelan66) These differences in socioeconomic status have been proposed to be one mechanism through which racism leads to health disparities.(Reference Harrell, Burford and Cage67) In the face of these underlying racial disparities in wealth, income, education and occupational status, interventions focused on proximate causes of health disparities (such as food choice) will not eliminate these disparities.(Reference Hummer and Hamilton68) Our results demonstrate that few nutrition-focused interventions have attempted to address disparities in social and economic resources or remove deterrents to healthful eating patterns that disproportionately affect African Americans. Future work should work to fill this gap in the literature and investigate interventions conducted with African Americans which address these aspects of the framework.

Structural racism also affects other marginalised populations’ ability to access enough healthful, culturally appropriate food, including Hispanic Americans and Indigenous populations. Researchers have acknowledged and studied the effects of structural racism on food insecurity, obesity and nutritional status in these populations and have called for efforts to address these disparities.(Reference Singleton, Uy and Landry7,Reference Odoms-Young10,Reference Dougherty, Golden and Gross69) Despite this, no other scoping reviews have been published to date which examine interventions to address structural racism in the food environment among these populations in the United States. Reviews have examined ‘culturally adapted’ or ‘culturally tailored’ nutrition education and health promotion interventions in Hispanic and Indigenous populations.(Reference Joo and Liu70–Reference Vincze, Barnes and Somerville72) A recent scoping review of family-based obesity prevention programmes conducted with Hispanic audiences found that only half of the interventions acknowledged the role of social determinants of health in obesity.(Reference Soltero, Peña and Gonzalez73) It will be particularly important for future work to address structural barriers to healthful eating among Native Americans in the United States. Despite similar rates of food insecurity and poverty among Native Americans compared with African Americans, a 2020 review of dietary policies and programmes in the United States found that only a small percentage of included studies aimed to benefit Native Americans, while African American populations were well studied.(Reference Russo, Li and Chong74)

Despite the limitations of interventions which focus on proximal causes of disparities in nutritional status, our results have implications for federally funded nutrition programmes and other implementers of programmes that are required to focus on these proximal causes through nutrition education and nutrition-focused PSE changes. Our results map out existing strategies that have been implemented in an attempt to address structural barriers to healthful eating among African Americans, and these strategies may serve as examples that federally funded nutrition education programmes may wish to implement or build upon. Studies which met our inclusion criteria implemented diverse strategies to address structural racism, and very few of these studies attempted to do so through direct education alone. For example, the interventions which resulted in positive changes to fruit and vegetable consumption included PSE interventions at majority African American churches,(Reference Baruth and Wilcox38,Reference Campbell, Demark-Wahnefried and Symons51) community gardens(Reference Baker, Motton and Seiler57) and farmers’ market vouchers.(Reference Stallings, Gazmararian and Goodman43) All three of the interventions in this review which resulted in weight loss consisted of combined nutrition education and environmental changes, either through community gardens,(Reference Barnidge, Baker and Schootman42) changes to the school environment(Reference Choudhry, McClinton-Powell and Solomon52) or changes at multiple locations in a community.(Reference Ard, Carson and Shikany50) These combinations of education and PSE interventions and/or multi-level, multi-component interventions may be more effective in supporting healthful eating choices than approaches using direct education alone.(Reference Trude, Surkan and Cheskin29,Reference Ewart-Pierce, Ruiz and Gittelsohn75) Guidance provided for obesity prevention programmes such as SNAP-Ed has also encouraged the use of direct education in combination with multi-level, multi-component interventions.(76) Our results indicate that the majority of the approaches to address structural racism in African Americans’ food environment which implemented direct education did so in combination with a PSE change intervention. Those public health practitioners implementing nutrition education and/or PSE change interventions who wish to refocus their efforts to better address structural racism should therefore consider implementing interventions which combine PSE changes and nutrition education.

Nutrition researchers and public health professionals have recently renewed calls for efforts to address structural racism and its effects on the nutritional status of marginalised groups.(Reference Singleton, Uy and Landry7,8,Reference Aaron and Stanford77) Our results demonstrate that, despite these calls to action, few studies have been published that have addressed the issue, and even fewer have addressed aspects of the ‘Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention’ framework that may be best suited to addressing the problem, improving social and economic resources of African Americans and reducing deterrents to healthy behaviours. Future work will need to address this gap in the literature, by linking programmes which provide targeted economic assistance to African Americans to nutritional outcomes, or by examining the effects of interventions which reduce deterrents, such as providing point-of-choice nutritional information targeted to African Americans. Researchers will also need to address the lack of literature describing nutrition interventions in other marginalised populations to address structural racism, and may wish to use methods similar to ours to describe the available literature concerning those populations.

In addition to these implications for research, our results may help inform public health nutrition practice. Those practitioners whose funding sources specify that they may only implement nutrition education and PSE changes but wish to address structural barriers too may consider implementing combined PSE change and nutrition education interventions like those described in our results, such as in church or school settings. Although nutrition education and PSE changes will not sufficiently address underlying causes of health disparities, our results demonstrated that several interventions had positive outcomes such as weight loss and increased fruit and vegetable intake. Those practitioners without those restrictions or who are already implementing interventions to address structural racism faced by African Americans should work to implement interventions which work to address underlying causes of racial health disparities and the other aspects of the ‘Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention framework’.

Limitations

While our search was guided by a research librarian (R.L.M.), it was limited to five databases of peer-reviewed literature. These databases were selected based on the interdisciplinary nature of this investigation, but there may have been additional articles available in other databases that were not included in this review. Additionally, the grey literature search was limited to a search of one database of dissertation and theses. There may be additional dissertations and theses related to the subject that were not available in this database.

Our investigation only addressed nutrition education and PSE interventions benefitting African Americans. Other marginalised populations in the United States experience structural racism in their food environments, and further reviews should address interventions conducted with these populations. There may be interventions which have addressed structural barriers to healthy eating conducted with other marginalised populations that could also be beneficial for African Americans.

Possibly the most serious limitation of our review is the lack of evidence produced by academic institutions and public health nutrition practitioners that directly addressed our research question. Academic institutions are not immune to the effects of ‘colour-blind’ racism and ideologies of white supremacy.(Reference Gray, Joseph and Glover78,Reference Nardi, Waite and Nowak79) It may therefore have been misguided to search for solutions to address structural racism in the food environment which originated from these institutions. Although we hope that this investigation will serve as a starting point for future work and illustrate gaps in the literature, future work may need to look for answers in spaces beyond the peer-reviewed and grey literature and examine efforts that have not been described in these publications.

Conclusion

Public health professionals are increasingly developing an understanding of how structural racism produces racial health and obesity disparities in the United States.(Reference Bailey, Krieger and Agénor4,Reference Aaron and Stanford77) Nutrition educators have also acknowledged that providing education alone is not enough to change nutrition behaviours, and that influences on nutrition behaviour exist beyond the control of individuals.(Reference Mancino and Kinsey12,Reference Braun, Bruns and Cronk80) This scoping review has described the available literature reporting interventions addressing structural racism affecting African Americans through nutrition education or other nutrition-focused PSE changes and compared those results with the ‘Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention’ framework. Results demonstrated that nearly all articles addressed the issue by providing additional healthy options or nutrition education, charitable strategies which do not address underlying causes of racial disparities in nutritional status. More work will need to be done to address other aspects of the framework, including reducing deterrents to healthy eating and improving social and economic resources of African Americans. Because African Americans experience high rates of obesity and food insecurity and encounter structural barriers to healthy eating in their food environment, researchers should address these gaps in the literature if they seek to serve this population adequately.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Authorship

M.G., D.H. and R.M. conceptualised the review. M.G. and R.M. designed the search strategy. M.G. and D.H. independently performed the initial title and abstract screen and the full-text screen for inclusion. M.G., B.H., C.S., M.D.M. and D.B. performed data extraction. M.G. wrote the first draft of the manuscript with contributions from R.M. All authors contributed to, reviewed, edited and commented on subsequent drafts of the manuscript.