Introduction

Takeaway, take-out and fast foods are common terminology used for various ‘out-of-home’ foods. ‘Takeaway foods’, commonly used in the UK and Australia, are defined as hot meals made to order and take away from small, independent outlets( Reference Miura, Giskes and Turrell 1 , Reference Jaworowska, Blackham and Long 2 ) whereas in the USA ‘take-out’ shares a similar definition. ‘Fast food’ mainly defines foods from national/multinational fast food chains (such as McDonald’s, Domino’s Pizza, Subway, Burger King, Pizza Hut, Kentucky Fried Chicken and Taco Bell)( Reference Block, Scribner and DeSalvo 3 – Reference Bauer, Hearst and Earnest 5 ) and can include dining in. However, ‘out-of-home’ foods do include multiple definitions and can come from a number of sources including vending machines, convenience stores, fast food outlets, takeaway food outlets, coffee shops, schools, etc.( Reference Nago, Lachat and Dossa 6 ). For the purpose of the present review, the terminology from the original articles reviewed has been maintained to represent the subtle differences between studies. Therefore, the terminology used by the authors has also been used interchangeably dependent on the literature in review. In instances of critique and where multiple studies are being discussed, ‘out-of-home foods’ has been used as this term broadly covers takeaway and fast food. Out-of-home foods have become increasingly popular over the past few decades and are thought to be one of the key proponents driving increasing levels of overweight and obese individuals( Reference Lachat, Nago and Verstraeten 7 ). The causes of obesity are complex( Reference Butland, Jebb and Kopelman 8 ) but the overconsumption of food and sugar-sweetened beverages, along with increased portion sizes, are also undoubtedly strong determinants( Reference Marteau, Hollands and Shemilt 9 ). A recent UK study found that 27 % of adults and 19 % of children consumed meals outside the home once per week or more and 21 % of adults and children ate takeaway meals at home once per week or more( Reference Adams, Goffe and Brown 10 ). Similar consumption patterns are common in other high-income and urban societies; particularly those in Europe, the USA and Australia( Reference Guthrie, Lin and Frazao 11 , Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulos 12 ). Kant et al. ( Reference Kant, Whitley and Graubard 13 ) found that more than 50 % of US adults reported consuming three or more out-of-home meals per week and more than 35 % reported consuming two or more fast food meals per week. While the majority of the research based on out-of-home foods has been undertaken in Australia, the UK and the USA, the same issues (poor dietary habits and increased prevalence of non-communicable disease) are of equal concern for urban centres in developing economies undergoing ‘nutrition transition’ in other parts of the world, such as Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America( Reference Popkin and Gordon-Larsen 14 ). Out-of-home foods tend to be less healthy, because they are more energy dense and nutrient poor, than foods prepared at home( Reference Lachat, Nago and Verstraeten 7 , Reference Nguyen and Powell 15 ). They often contain high quantities of unhealthy ingredients, including fat, salt and sugar, which are associated with weight gain and a variety of negative health outcomes( Reference Jaworowska, Blackham and Long 2 , Reference Duffey, Gordon-Larsen and Steffen 16 , Reference Jaworowska, Blackham and Stevenson 17 ). Frequent consumption of fast food and takeaway food has been associated with higher BMI and biomarkers of greater cardiometabolic risk( Reference Kant, Whitley and Graubard 13 , Reference Duffey, Gordon-Larsen and Steffen 16 , Reference Smith, Blizzard and McNaughton 18 ). While there is a consensus that being overweight (BMI 25–29·9 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)( 19 , 20 ) is associated with high consumption of energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods, the factors influencing their consumption are not well understood. Furthermore, there is no single causative factor to becoming overweight or obese although unhealthy dietary patterns are considered a key factor( Reference Butland, Jebb and Kopelman 8 ) that warrant intense investigation.

Recommendations and interventions have been implemented across the globe to challenge the rise in diet-related non-communicable diseases. In the UK, local government initiatives have aimed to tackle the impacts of takeaway food in local communities by working with the takeaway food industry to reformulate foods; reducing the amount of fast food consumed by school children; and addressing the proliferation of hot food takeaway outlets through planning regulations( 21 , 22 ). In Australia, the methods used to impede out-of-home food consumption have included a ban of fast food advertisements between 06·00 and 21·00 hours, a ban on takeaway outlets opening within 400 m of schools or leisure centres and taxes on high-fat fast foods and sugar-sweetened beverages( 23 ). Alternative interventions have been implemented in the USA; menu labelling of energy became law in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act( 24 ). In New York, consumer awareness of the energy information was assessed pre- and post-intervention and indicated that menu labelling on fast food generated a 2-fold increase in the percentage of customers making energy-informed choices( Reference Dumanovsky, Huang and Bassett 25 ). Nonetheless, the US Food and Drug Administration extended the compliance date to 5 May 2017, due to non-compliance in some states. In order to create effective public health interventions in relation to out-of-home food and obesity, it is necessary to explore the determinants of their consumption. Individual food choices and eating behaviours are influenced by many interrelated factors including cultural, environmental, demographic, biological, cognitive and behavioural( Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien 26 , Reference Franchi 27 ). Therefore, the overall aim of the present narrative review is to collate the existing research and provide a holistic overview of the key areas that make an impact on out-of-home food consumption, with a view to suggest future directions and recommendations.

Methods

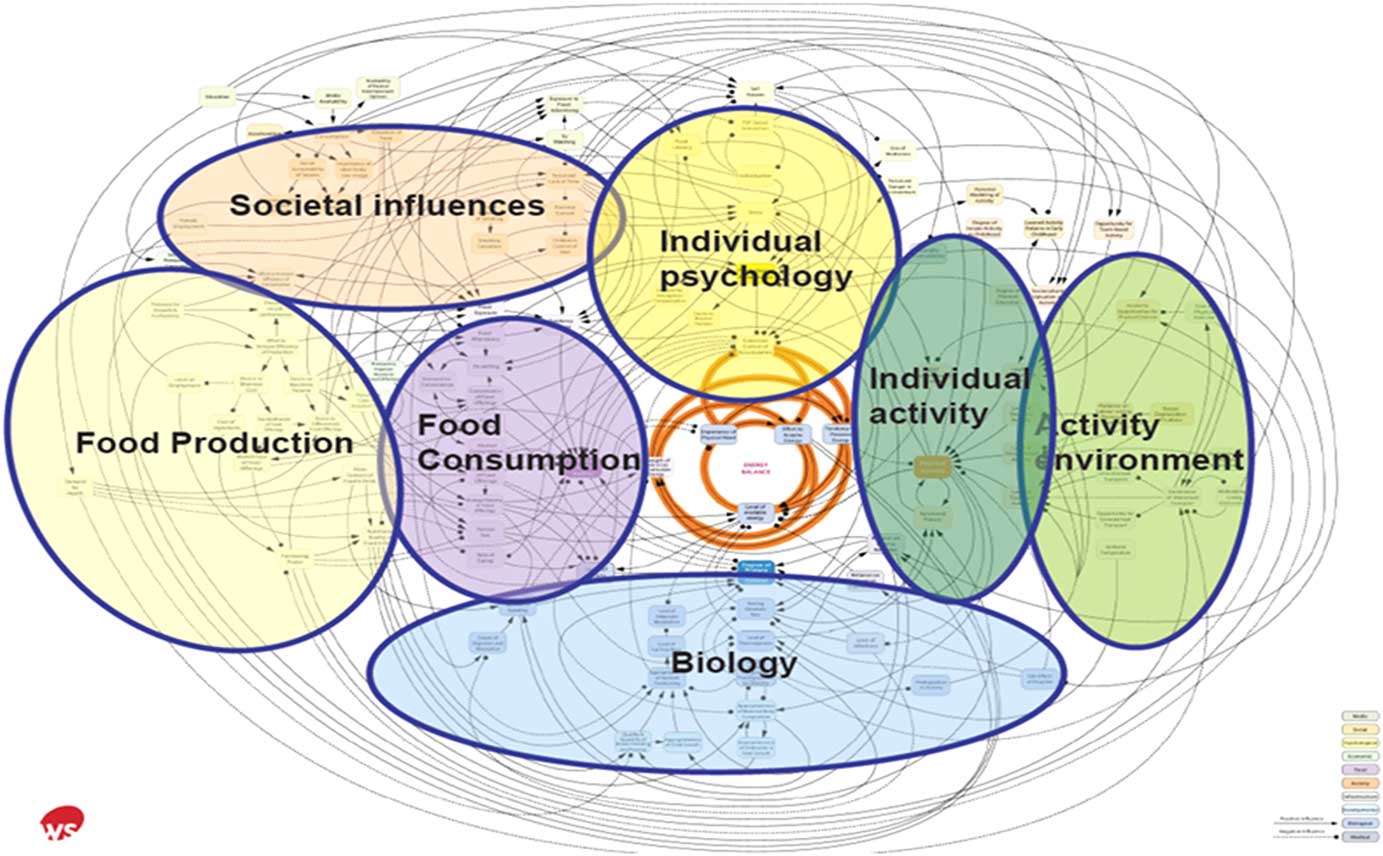

Literature searches were performed using the following electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Science Direct, Google and Google Scholar up to February 2017. The findings of the literature, retrieved from searches of computerised databases, were then disseminated into a coherent narrative review. The following key words were used: ‘fast food’, ‘takeaway food’, ‘take-away food’, ‘takeout’, ‘Western diet’, ‘obesity’, ‘food outlets’, ‘factors of consumption’, ‘determinants of consumption’, ‘foodscape’, ‘food environment’, ‘out-of-home food’, ‘consumers’, ‘socio-demographic correlates’, ‘socio-economic differences’, ‘food availability’, ‘food choice’, ‘food behaviour’, ‘unhealthy eating’ and ‘nutrition transition’. Additionally, key words were supplemented via a ‘snowball method’ in which references from relevant articles were reviewed and selected to find other studies. Articles were limited to human participants only and papers in the English language only were included. Despite slight variations between some of the definitions of fast food and takeaway food, the nutritional composition of both types of food is predominately unfavourable; therefore, literature on both definitions was included. The terminology used in this review fluctuates to represent the original studies. Therefore, the terminology used by the authors is dependent on the literature in review; in instances where both ‘takeaway’ and ‘fast foods’ are discussed, the term ‘out-of-home foods’ has been used. The different thematic factors associated with out-of-home food consumption were identified according to the Foresight obesity system map (Fig. 1)( 28 ). Themes were adjusted to be more applicable to out-of-home food and significant factors including demographic and socio-economic differences were added. Recommendations for future research in this area are also presented.

Fig. 1 Foresight obesity system map with thematic clusters( Reference Butland, Jebb and Kopelman 8 ).

Out-of-home food consumption

Numerous studies have shown increasing trends in frequency of out-of-home food consumption, predominately in Europe, USA and Australia( Reference Guthrie, Lin and Frazao 11 , Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulos 12 ). Yet, emerging research from low- and middle-income countries including Brazil( Reference Monteiro, Levy and Claro 29 ), Chile( Reference Albala, Vio and Kain 30 ), India( Reference Singh, Gupta and Ghosh 31 ), Iran( Reference Bahadoran, Mirmiran and Golzarand 32 ), Malaysia( Reference Fournier, Tibere and Laporte 33 ), Kenya and Tanzania( Reference Keding 34 ), among others, have presented similar findings; suggesting a transition to a ‘Western diet’. The Western-type diet pattern comprises overconsumption of sweets, desserts, soft drinks, red meat, processed meats and high-fat dairy products, with a lower consumption of fish (n-3 fatty acids), whole grains, fruit and vegetables( Reference Hu, Rimm and Stampfer 35 ). Western-type diet patterns have become deeply embedded within many societies and despite pressing health-related issues continue to grow( Reference Popkin 36 , Reference Jaworowska, Blackham and Davies 37 ). In the UK, a government report based on cross-sectional data indicated that 22 % of residents purchased takeaway food at least once per week and 58 % a few times per month( 38 ). When analysed longitudinally, time devoted to eating and drinking away from home increased significantly in the UK between 1975 and 2000( Reference Cheng, Olsen and Southerton 39 ), which concords with the increased prevalence of out-of-home eating establishments seen in parts of the UK between 1980 and 2000( Reference Burgoine, Lake and Stamp 40 ). Similarly, a US study showed fast food consumption in children increased 300 % between the period of 1977 to 1996( Reference Fraser, Edwards and Cade 41 ). Times of relative scarcity (lack of readily available foods) have receded into an era of availability (abundance of readily available high-energy-dense foods) and although most Western societies have managed to successfully reduce the burden of infectious disease, the current environment promotes a whole spectrum of dietary induced diseases( Reference Manzel, Muller and Hafler 42 ). That said, low- and middle-income countries with existing undernutrition and infectious diseases, that are undergoing development, urbanisation and nutrition transition, are now also experiencing a double burden of non-communicable diseases( Reference Agyei-Mensah and de-Graft Aikins 43 – Reference Shetty 45 ), therefore, highlighting the urgency of research on out-of-home foods.

Diet is a modifiable determinant of health; however, societies portraying a ‘Westernised’ lifestyle are consuming diets high in out-of-home foods and experiencing a prevalence of obesity( Reference Duffey, Gordon-Larsen and Steffen 16 , Reference Anderson, Key and Norat 46 ). The challenges in considering the effects of fast foods are not solely related to the nutritional composition, but are also dependent on expanding portion sizes( Reference Young and Nestle 47 ). Poor diet and obesity in turn predispose humans to CVD( Reference Smith, Blizzard and McNaughton 18 , Reference Mente, de Koning and Shannon 48 , Reference Carrera-Bastos, Fontes-Villalba and O’Keefe 49 ), type 2 diabetes( Reference van Dam, Rimm and Willett 50 , Reference Pereira, Kartashov and Ebbeling 51 ) and various cancers( Reference Anderson, Key and Norat 46 ). Interestingly, obesity rates can vary substantially between nations: England had a prevalence of 24·8 % in 2011; however, neighbouring European countries demonstrated much lower rates such as France (12·9 %; 2010), Belgium (13·8 %; 2008) and the Netherlands (11·4 %; 2010)( 52 ); suggesting that cultural differences could be a contributing factor. Urban and rural communities in developing economies have also shown contrasting dietary patterns and consequent obesity( Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng 53 ).

Societal influences

Food messages are delivered to a wide demographic through multiple techniques and channels including advertisements and television( Reference Story and French 54 ). The trend emerging in the dietary patterns of the world has particularly encouraged an obesogenic culture of eating among adolescents( Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett 55 ). Fast food has been seen as a key aspect of youth identity, a way of expressing a youthful self and lifestyle image, whereas healthy food has been shown to conflict with the normal image of being young( Reference Ioannou 56 ). Food identity refers to individuals choosing or feeling pressured to eat in a manner that is influenced by others; to project a social or political statement within certain groups. According to Stok et al. ( Reference Stok, de Vet and de Wit 57 ), subjective peer norms play an important role in adolescent eating behaviour, above and beyond sociodemographic variables (Table 1). A recent review on dietary behaviour in youth found consistent evidence that suggested that individual unhealthy food consumption was associated with peer unhealthy food consumption( Reference Sawka, McCormack and Nettel-Aguirre 58 ). Nonetheless, it must be noted that out-of-home food consumption can be affected by individual experiences, behaviours and attitude (which are discussed in later sections). Contrary to this, healthier eating practices are becoming increasingly popular among younger age groups due to appearance pressures( Reference Bugge 59 ).

Table 1 Summary of studies investigating the effects of societal influences and/or individual activities on out-of-home food consumption

Other individuals chose fast food restaurants as a way to spend time with friends, family or someone special( Reference Srivastava 60 ). Studies have suggested culturally agreed norms where individuals consume more when in a group or with friends, rather than alone( Reference Cavazza, Graziani and Guidetti 61 , Reference Higgs and Thomas 62 ). A recent study by Higgs & Thomas( Reference Higgs and Thomas 62 ) also explored the social influences of eating including the phenomenon of ‘modelling’ food consumption, when the norm is set by another individual with or without their presence. Environmental cues such as empty food wrappers and contextual information such as providing information about what others have eaten can all trigger increased consumption( Reference Higgs and Thomas 62 ). Finally, individuals can be pressured by others to make certain food choices. In New Zealand, Maubach et al. ( Reference Maubach, Hoek and McCreanor 63 ) researched the considerations of parents when shopping for their families, and found that price, marketing and children altered food choice (Table 1). Thus parents may experience family pressure to purchase out-of-home foods, despite having other views based on nutritional knowledge( Reference Maubach, Hoek and McCreanor 63 ). Findings from the discussed studies suggest that social influences on food consumption could play an important role in the development and maintenance of obesity.

Individual activity

Over the past few decades the development of convenient out-of-home food has competed successfully against home-prepared food in Western societies( Reference Guthrie, Lin and Frazao 11 , Reference Trapp, Hickling and Christian 64 ). Economic development and rapid urbanisation in non-Western areas of the world, such as China, have also driven a change in consumption patterns and eating and cooking behaviours( Reference Zhai, Du and Wang 65 ). A large-scale study by Smith et al. ( Reference Smith, Emmett and Newby 66 ) showed a shift in dietary patterns and food preparation since 1965 due to a significant decline in time spent cooking in the home and growing trends in out-of-home food consumption. It is now thought that US adults consume two-thirds of their daily intake from home sources and the remaining third from out-of-home sources, including fast food and restaurants( Reference Smith, Emmett and Newby 66 ). A UK study aiming to document the prevalence of time spent cooking in 2005 showed that 60 % of women and 33 % of men reported spending 30 min of continuous cooking daily( Reference Adams and White 67 ). Less time spent cooking could be an indicator of increased consumption of convenience foods( Reference Jackson and Viehoff 68 ). The findings also suggested that being female was the main determinant of time spent cooking, with little influence from older age, greater education, unemployment, lower social class and living with others( Reference Adams and White 67 ). Nevertheless, the level of attrition within the study was substantial and could introduce bias. Furthermore, data collected in 2005 may not represent accurately more recent trends.

The shift in out-of-home food choice coupled with an increase in sedentary behaviour has contributed to an obesity epidemic in the 21st century( Reference Lachat, Nago and Verstraeten 7 , Reference Jacobs 69 , Reference Pieroni and Salmasi 70 ). Lowry et al. ( Reference Lowry, Michael and Demissie 71 ) reported a positive association between television/computer screen time and consumption of fast food and sugar-sweetened beverages in a sample of students (Table 1). The findings suggested a pattern of unhealthy behaviours, which support previous research stating that television viewing and fast food consumption were positively associated with BMI( Reference Jeffery and French 72 ). The use of out-of-home foods may also be attributable to individuals working more and experiencing feelings of time scarcity( Reference Celnik, Gillespie and Lean 73 , Reference Devine, Farrell and Blake 74 ); this has been especially evident among women (Table 1)( Reference French, Story and Jeffery 75 – Reference Welch, McNaughton and Hunter 77 ). Urbanisation, economic growth and educational achievement in low- and middle- income countries have all been shown to influence the consumption of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods( Reference Malik, Willett and Hu 78 ). One study presented findings that individuals seeking professional success wanted to avoid spending time and effort clearing up after meals, to create time for other activities (Table 1)( Reference Botonaki and Mattas 79 ). As a result, it would appear that the time constraints of working long hours coupled with the advances of new technology may contribute to an increase in people’s consumption of out-of-home energy-dense foods( Reference Pieroni and Salmasi 70 ).

Food environment

The food environment (or ‘foodscape’) has been extensively studied over the last 20 years, with a major increase in out-of-home food establishments that is concordant with the proliferation of obesity( Reference Burgoine, Forouhi and Griffin 80 ). A review by Albuquerque et al. ( Reference Albuquerque, Stice and Rodríguez-López 81 , Reference Allison, Matz and Pietrobelli 82 ) acknowledged the importance of genetic factors in the aetiology of obesity and inferred that natural selection has assisted the spread of genes that increase the risk for an obese phenotype. However, cumulatively all genomic markers along with their presumptive genes have only been shown to have small effects on BMI (less than 5 % of the total heritability)( Reference Speliotes, Willer and Berndt 83 ) and risk of obesity( Reference Tan, Zhu and He 84 ), further suggesting that obesity is more likely to be contextual (environmental influences that cause its inhabitants to become obese). Environments that encourage the consumption of food and/or discourage physical activity have been labelled ‘obesogenic’ (Table 2)( Reference Reidpath, Burns and Garrard 85 ). In Norfolk, UK, the number of takeaway outlets was reported to have grown by 45 % between 1990 and 2008, a trend which has been reflected across the rest of the UK( Reference Maguire, Burgoine and Monsivais 86 ). This abundance of unhealthy and energy-dense food in the environment, noted by Feng et al. ( Reference Feng, Glass and Curriero 87 ), has been shown to disrupt an individual’s ability to make healthy food choices( Reference Maguire, Burgoine and Monsivais 86 ). A number of US studies have demonstrated that neighbourhood exposure to fast food outlets increased consumption near the home in addition to contributing to a poor diet (Table 2)( Reference Moore, Diez Roux and Nettleton 88 , Reference Athens, Duncan and Elbel 89 ). A prospective study across a 1-year period found that neighbourhoods with a high density of fast food outlets promoted an increase in weight and waist circumference in those who visited frequently( Reference Li, Harmer and Cardinal 90 ). Nevertheless, the link between neighbourhood availability of out-of-home food and a higher BMI and greater odds of obesity( Reference Burgoine, Lake and Stamp 40 , Reference Burgoine, Forouhi and Griffin 80 , Reference Li, Harmer and Cardinal 91 ) has been challenged. For example, Turrell & Giskes( Reference Turrell and Giskes 92 ) reported no relationship between the purchasing of takeaway food, road distance to the closest takeaway outlets and the number of takeaway outlets in the local food environment of Brisbane, Australia. They found that dietary inequalities between socio-economic groups appeared to have a stronger influence on the purchasing of takeaway food( Reference Turrell and Giskes 92 ). This suggests that the food environment may be more complex, with economic and sociocultural factors potentially influencing food consumption and food-related behaviours( Reference Giskes, van Lenthe and Avendano-Pabon 93 ). Whilst many of these studies may not capture the full complexity of the food environment it must be noted that an additional layer of research involving individual interactions or response to that environment( Reference Cerin, Mitáš and Cain 94 ) also requires further investigation.

Table 2 Summary of studies investigating the effects of the food environment and/or socio-economic differences on out-of-home food intake

SES, socio-economic status, GIS, geographic information system.

The many studies referring to ‘obesogenic environments’ make simple correlations between environment and obesity and do not explore the sociological and behavioural determinants of food consumption. For example, a large study by Pieroni & Salmasi( Reference Pieroni and Salmasi 70 ) stated that there was a clear correlation, but no causal relationship, with the higher availability of fast food outlets and increased BMI (Table 2). In a more recent study, Polsky et al. ( Reference Polsky, Moineddin and Dunn 95 ) reported an increase in obesity figures among adults living in close proximity to a number of fast food outlets, suggesting that a food environment with a high occupancy of fast food outlets is most likely to make an impact on weight status (Table 2). Overall, the literature suggests that the food environment is an important factor to consider when contemplating the reasons for out-of-home food consumption and is a potential target for change. However, other factors including age group, socio-economic status and culture are considered important influences and it is often impossible to differentiate the cause and effect, especially within a cross-sectional design study. Likewise, the food environment is regarded as merely one factor in the causes of obesity, which are complex and multifaceted( Reference Butland, Jebb and Kopelman 8 ).

Socio-economic differences

An unequal distribution of health – geographically, ethnically and socially – has detrimental effects on those of low socio-economic status( Reference Wilkinson and Pickett 96 ). In the USA, research has shown that the rates of obesity and poor health were most prevalent in the least educated and poverty-stricken population groups( Reference Drewnowski and Specter 97 , Reference Braveman, Cubbin and Egerter 98 ). Studies in the UK investigating neighbourhood deprivation and access to fast food outlets have found an association with increased levels of obesity( Reference Maguire, Burgoine and Monsivais 86 , Reference Cummins, McKay and MacIntyre 99 , Reference Macdonald, Cummins and Macintyre 100 ). A recent report showed a strong link between deprivation and density of fast food outlets, with deprived areas having more fast food outlets per 100000 of the population( 101 ). These findings corroborate those in Australia( Reference Reidpath, Burns and Garrard 85 ), New Zealand( Reference Pearce, Blakely and Witten 102 , Reference Utter, Denny and Crengle 103 ), Germany( Reference Schneider and Gruber 104 ), Canada( Reference Smoyer-Tomic, Spence and Raine 105 ) and the USA( Reference Zenk and Powell 106 ), where it has been observed that those living in the poorest areas had a higher exposure to fast food outlets than those in less deprived areas (Table 2). In contrast, high socio-economic status and urban residence were associated with the consumption of energy-dense foods in adolescents in China( Reference Shi, Lien and Kumar 107 ), suggesting accelerated nutrition transition within communities experiencing economic growth. However, in West Africa( Reference Zeba, Delisle and Renier 108 ), Bangladesh( Reference Shafique, Akhter and Stallkamp 109 ) and Indonesia( Reference Hanandita and Tampubolon 110 ), income inequality and economic development have been shown to increase the odds of a double burden of malnutrition; the coexistence of both under- and overweight. In Scotland, UK, consumption of takeaway food was significantly higher in the most deprived quintile( Reference Barton, Wrieden and Sherriff 111 ). Research from Australia investigating the frequency and types of takeaway foods consumed by different socio-economic groups found that individuals from disadvantaged groups were consistently consuming less healthy takeaways than those from advantaged groups (Table 2)( Reference Miura, Giskes and Turrell 1 , Reference Miura, Giskes and Turrell 112 ). Lake et al. ( Reference Lake, Hyland and Rugg-Gunn 113 ) explored perceptions and practice of healthy eating and reported that individuals from a higher socio-economic group were more likely to agree with the statement ‘my eating patterns are healthy’. Despite some conflicting findings between the effects of socio-economic status on the food environment and out-of-home consumption, the greater part of the literature suggests that those from lower socio-economic groups would be more susceptible to inequalities in diet and as a result obesity and chronic disease.

Other studies on the socio-economic disparities in the food environment have concentrated on the notion of food security; defined by the 1996 World Food Summit as ‘a situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’( 114 ). Food insecurity, on the other hand, refers to the limited access to affordable, quality and nutritious food, but also with restrictions on the facilities to store, cook and consume those foods( Reference Borch and Kjaernes 115 ). A mail survey on adults from disadvantaged suburbs of Brisbane city, Australia, reported that approximately one in four households were food insecure based on results from an eighteen-item food security screening questionnaire( Reference Ramsey, Giskes and Turrell 116 ). The economic and physical access constraints to nutritious food in deprived areas have contributed to what are sometimes defined as ‘food deserts’( Reference Whelan, Wrigley and Warm 117 , Reference Wrigley 118 ). A particularly interesting finding from the Brisbane study was that food-insecure households were two and a half times more likely to report more frequent hamburger consumption compared with those who were not food insecure( Reference Ramsey, Giskes and Turrell 116 ). These findings support the notion that food insecurity may encourage the purchasing of out-of-home food, especially in deprived areas( Reference Hendrickson, Smith and Eikenberry 119 ). Thus, targeting areas of high deprivation and ensuring food security may be a strategy for facilitating healthy eating( Reference Trapp, Hickling and Christian 64 ).

Less healthy takeaway food choice has been shown to be associated with a poorer level of education( Reference Miura, Giskes and Turrell 1 , Reference Miura, Giskes and Turrell 112 ). However, research suggests that poor health literacy is a stronger predictor of health than variables such as age, ethnicity, income, employment status and education level( 120 ) and is recognised as a cause of health inequalities in both rich and poor countries( Reference Marmot 121 ). Health literacy refers to an individual’s knowledge and skills in matters of health and illness( Reference Nutbeam 122 ). Boulos( Reference Boulos 123 ) stated that most written resources containing health information were deemed too advanced for the general UK population, with an average reading age of nine. Thus, it was found that limited health literacy was related to unhealthy lifestyle behaviours such as poor diet( 124 ). An emerging concept is food literacy that encompasses individual food skills, community food security and health literacy( Reference Cullen, Hatch and Martin 125 ). Carbone & Zoellner( Reference Carbone and Zoellner 126 ) specified that literacy was a determinant of dietary patterns and that increased food literacy was positively associated with healthier eating practices. For example, a study on young adults reported that those with low levels of health literacy used food labels significantly less( Reference Cha, Kim and Lerner 127 ), suggesting that their food choices were less informed by nutrition information. Therefore, it would appear crucial to consider literacy levels when conducting any out-of-home food intervention or research. Some nutrition studies include validated health literacy assessments to understand participant knowledge of aspects, such as nutrition facts labels, and how they might interpret or act upon the information( Reference Zoellner, Krzeski and Harden 128 ). Conversely, even if the population had increased health or food literacy, conflicting food messages from a myriad of sources means making healthy choices challenging for society.

Food production and cost

The growing success of the fast food industry is based upon food that is quick, convenient and uniform in production( Reference DeMaria 129 ). Competing consumer demands and preferences could also be responsible for increased out-of-home food intake. The combined use of sugar, fat and salt is common in the food industry to enhance palatability and can also act as cheap bulking agents( Reference Glanz, Basil and Maibach 130 ). Developed economies are known to be using high levels of salt, fat and sugar in takeaway food( Reference Jaworowska, Blackham and Long 2 ) but a similar global trend has also been seen in populations from developing economies such as South East Asia( Reference Baker and Friel 131 ). Those on a lower income have argued that higher-energy-dense food is cheaper than lower-energy-dense food( Reference Davis and Carlson 132 ). Yet, in the USA, Davis & Carlson( Reference Davis and Carlson 132 ) found no statistical support that higher-energy-dense food was cheaper and stated that the relationship between price and energy density was indeed the opposite (Table 3). Similarly, a study in Sweden stated that the cost of nutritious food did not increase, between 1980 and 2012, more than the cost of food in general (Table 3)( Reference Håkansson 133 ). However, both sets of results were not without limitations; the studies may not be universally representative, suggesting that alternative studies using the same method, during other time periods, locations and foods, could yield different findings.

Table 3 Summary of studies investigating food prices of energy-dense and/or nutritious foods

NDNS, National Diet and Nutrition Survey; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; CNPP, Centre for Nutrition Policy and Promotions.

The argument that healthy food costs more also relies on how to measure cost, since energy from different sources is not equal. Monsivais & Drewnowski( Reference Monsivais and Drewnowski 134 ) evidenced that energy-dense foods were least expensive and most resilient to inflation. Monsivais et al. ( Reference Monsivais, McLain and Drewnowski 135 ) then furthered this research by using a sophisticated technique to investigate food cost based on nutrient density across a 4-year time period (Table 3). The results showed an increasing disparity between the price of nutrient-dense foods and less nutrient-dense foods( Reference Monsivais, McLain and Drewnowski 135 ). An additional study analysing the macronutrient content of 106 foods reported that protein increased the cost of food and carbohydrate reduced the cost of food (Table 3)( Reference Brooks, Simpson and Raubenheimer 136 ). Furthermore, a recent UK study found that healthy foods were approximately three times more expensive than unhealthier foods per 100 kcal (418 kJ) and that the rise in price over the 10-year period was steeper for healthy foods (Table 3)( Reference Jones, Conklin and Suhrcke 137 ). A systematic review and meta-analysis of twenty-seven studies concluded that healthier diet patterns were on average about $1·50/d more expensive( Reference Rao, Afshin and Singh 138 ). Findings from the above studies suggest that healthier foods and beverages have been consistently more expensive than less healthy ones. A cross-sectional study on fast food consumption and body weight in the UK stated that lower-priced fast food meals and snacks were positively associated with increased weight, especially for the overweight and obese( Reference Pieroni and Salmasi 70 ). Moreover, exposure to increased numbers of out-of-home food outlets in economically deprived areas in conjunction with higher levels of food insecurity may exacerbate purchasing of out-of-home foods. It is important to note that the majority of the literature on cost of out-of-home food has been sourced from high-income countries, highlighting a need for similar studies in low- and middle-income nations. One systematic review on general food prices in 162 different countries suggested that those from poorer countries or the poorer households would be most adversely affected by a rise in cost( Reference Green, Cornelsen and Dangour 139 ); however, out-of-home foods were not debated.

Demographic

Previous research has categorised out-of-home food consumption according to gender. A study on Australian adults found that men consumed takeaway foods more frequently than women (Table 4)( Reference Smith, McNaughton and Gall 140 ). This could be explained in part by findings showing that gender was the strongest determinant of time spent cooking at home (as mentioned previously), with women more likely to be proponents( Reference Adams and White 67 ). Nevertheless, the same Australian research group reported an increased risk of cardiometabolic disease in young women who consumed takeaway foods twice per week or more( Reference Smith, Blizzard and McNaughton 18 ). A recent study suggested that older men’s dietary patterns were associated with cues for fast food outlets (Table 4)( Reference Mercille, Richard and Gauvin 141 ). Other studies observed that men received a higher proportion of their energy intake from foods prepared and consumed out of the home( Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulou 142 , Reference Vandevijvere, Lachat and Kolsteren 143 ). However, a UK study found that the only gender difference was seen in children; boys consumed more takeaway meals at home than girls (Table 4)( Reference Adams, Goffe and Brown 10 ). This suggested that alternative patterns of out-of-home eating existed in the UK or had altered in recent years( Reference Adams, Goffe and Brown 10 ). Other findings have suggested that women and older adults are more vulnerable to being overweight and obese, and inverse associations of nutritional biomarkers including vitamins D, E, C, B6, B12, folate and carotenoids, with increased consumption of out-of-home foods( Reference Kant, Whitley and Graubard 13 ). Therefore, despite some studies suggesting that males consume out-of-home foods more frequently, the health implications may not be as severe as those seen in females. The increased risk to females may be attributable to lower amounts of physical activity and/or a lower BMR than males. However, this is a speculation and thus requires further investigation.

Table 4 Summary of studies investigating out-of-home food consumption and demographic influences

PCA, principal component analysis; NuAge, Nutrition and Successful Aging; GIS, geographic information system; BiB, Born in Bradford; SES, socio-economic status.

In the UK, the consumption of meals out-of-home and takeaway meals at home was particularly widespread among the younger age groups and was shown to peak in those aged between 19 and 29 years( Reference Adams, Goffe and Brown 10 ). Previous studies reported comparable findings in other European countries( Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulou 142 – Reference O’Dwyer, Gibney and Burke 145 ), the USA( Reference Guthrie, Lin and Frazao 11 , Reference Kant and Graubard 146 ) and New Zealand( Reference Smith, Gray and Fleming 147 ). Likewise in Australia, consumption of takeaway was shown to increase from adolescence to young adulthood( Reference Smith, McNaughton and Gall 140 ) and a relatively high consumption of fast food occurred between the ages of 18 and 45 years (Table 4)( Reference Mohr, Wilson and Dunn 148 – Reference Dunn, Mohr and Wilson 150 ). In Vietnamese adolescents out-of-home food consumption was positively associated with residence in urban areas and amount of pocket money (Table 4)( Reference Lachat, Khanh le and Khan 151 ).

Many diet-related health issues stem from adolescence, a time when young people require an increase in nutrients( Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Wall and Story 152 , Reference Luszczynska, de Wit and de Vet 153 ) but often make unhealthy choices( Reference Dwyer, Evans and Stone 154 , Reference Slining, Mathias and Popkin 155 ). Fast food is considered important to adolescents because it is one of the limited types of food that is affordable amongst that group. Furthermore, the types of food consumed by young people are an important symbol of social and cultural belonging( Reference Bugge 59 ) and relate to food identity discussed earlier. A Swiss study that examined the importance of balanced food choices suggested that lack of cooking skills may play a part in driving younger age groups to consume more convenience foods (Table 4)( Reference Hartmann, Dohle and Siegrist 156 ). Statistics have shown a downward trend in consumption of both meals out and takeaway meals at home in older adults( Reference Adams, Goffe and Brown 10 ). Older age groups may have less disposable income( Reference Banks, Breeze and Crawford 157 ) and may find out-of-home foods unfamiliar, with a lack of exposure in younger years when eating habits develop( Reference Kant and Graubard 146 ). It must be noted that other reasons are also likely to be relevant and are yet to be discussed in this review.

In Los Angeles, USA, areas with a high population of immigrants lacking acculturation were associated with healthier dietary behaviour( Reference Zhang, van Meijgaard and Shi 158 ). Yet, according to Block et al. ( Reference Block, Scribner and DeSalvo 3 ), fast food outlets in New Orleans, USA, were geographically associated with predominately black and low-income neighbourhoods after controlling for environmental confounders (commercial activity, presence of highways, and median home values). Correspondingly, a study in Texas, USA, found that non-whites exhibited higher obesity rates, increased availability of fast food establishments in their local environment and higher consumption of fast food meals than their white counterparts( Reference Dunn, Sharkey and Horel 159 ). In the USA, one Puerto Rican immigrant described a feeling of ‘Americanness’ and belonging when dining out at fast food restaurants( Reference Wilkinson and Pickett 96 ), suggesting a ‘Westernised’ identity through the consumption of fast food. A study on the variations in fast food consumption in India reported that Indians preferred fast food from global chains compared with Indian fast food because they said that global brands were of better quality (Table 4)( Reference Srivastava 60 ). Likewise, minority ethnic groups of females living in the UK have incorporated the less healthy aspects of the Western diet including fast foods (such as fried fish, pizza, fries and fatty snack foods) into their diet when time was limited( Reference Lawrence, Devlin and Macaskill 160 ). However, a study in Bradford, UK, found a negative association between BMI and fast food outlet density in a South Asian group of women (Table 4)( Reference Fraser, Edwards and Tominitz 161 ), which would indicate a lack of acculturation. El-Sayed et al. ( Reference El-Sayed, Scarborough and Galea 162 ) stated that there was a lack of consensus regarding the aetiology of obesity and relative risk among large ethnic minority groups when compared with Caucasians in the UK. In a review, Fraser et al. ( Reference Fraser, Edwards and Tominitz 161 ) argued that there was little research conducted outside of the USA to explain whether ethnicity was related to access to and consumption of fast food. Additionally, ethnic minorities are disproportionately represented in low-income areas, thus socio-economic status is a confounding variable. Therefore, the limitations related to current research on ethnicity as a determinant of out-of-home food consumption warrant further investigation.

Biological

Humans have biological needs and adequate nutrition is regarded as essential, enabling a number of vital mechanisms to occur, to maintain homeostasis within the human body( Reference Burger and Berner 163 ). Genes have been shown to exert multiple and subtle influences on overall levels of nutrient intakes, meal sizes and frequencies( Reference de Castro 164 ). For example, internal and external cues can activate ghrelin, identified as the hunger hormone, which can affect appetite and adiposity, among other factors( Reference Pradhan, Samson and Sun 165 ). Hunger is known to increase motivation to seek out food, but, coupled with the bountiful availability of food in today’s environment, may trigger the brain reward system that evolved in environments of relative scarcity( Reference Berridge, Ho and Richard 166 ). A review on neuroimaging studies in obese participants provided evidence of altered control over appetite and the reward system, due to insulin resistance, reduced leptin secretion and other abnormal hormonal signals( Reference Wang, Volkow and Thanos 167 ). The reward deficiency syndrome, which represents a dysfunction or deficiency in the dopamine D2 receptor (a possible mediator of the rewarding property of palatable foods) has been considered a factor in the development of obesity, with many individuals demonstrating psychological dependence( Reference Wang, Volkow and Thanos 167 ). Other psychobiological personality traits including the ‘sensitivity to reward’ have been shown to make an indirect impact on weight status due to the availability of dopamine and level of activation in the mesocorticolimbic (reward) pathways in the midbrain (Table 5)( Reference Davis, Patte and Levitan 168 ).

Table 5 Summary of studies investigating biological and/or psychological effects of consuming palatable foods including out-of-home foods

STR, sensitivity to reward; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

A cross-sectional study in the USA reported that fast food consumption and BMI were correlated with impulsivity in adults (Table 5)( Reference Garza, Ding and Owensby 169 ). Previous studies have found a tendency to choose lesser immediate benefits of fast food intake over the longer-term health risks associated with unhealthy eating (Table 5)( Reference Maubach, Hoek and McCreanor 63 , Reference Dunn, Mohr and Wilson 149 , Reference Dunn, Mohr and Wilson 150 ). Neuroimaging studies in human subjects have shown activation sites in regions of the brain during impulsive moments, indicating a potential biological mechanism( Reference Boettiger, Mitchell and Tavares 170 ). Indeed, functional MRI studies show that the brain’s response to hunger and satiety during exposure to appetising food is somewhat driven by hedonic mechanisms( Reference Burger and Berner 163 ). ‘Hedonic’ hunger is a phenomenon which describes the way sensory factors including sight, smell and palatability combined with an availability of food can heighten appetite to a level that overwhelms the inborn control mechanisms( Reference Butland, Jebb and Kopelman 8 ). Fast food advertisements, outlets and menus provide environmental cues that can influence desirability( Reference Garber and Lustig 171 ). This aggressive style of out-of-home food marketing can lead to overindulging( Reference Davis, Patte and Levitan 168 ). The combination of food-associated cues, impulsive decision making and hedonic hunger is suggested to inhibit control over food cravings. A sample of students from an Australian university recalled their last food craving and revealed that visual imagery was the strongest determinant for food cravings, followed by gustatory and olfactory sensory triggers (Table 5)( Reference Tiggemann and Kemps 172 ).

Psychological

The range of determinants of out-of-home food consumption is broad and varies when viewed on an individual basis. Taste has been a fundamental determinant of highly palatable foods such as fast food (Table 5)( Reference Glanz, Basil and Maibach 130 ). The findings from a study conducted on Australian adults, between the ages of 18 and 45 years, suggested that fast food consumption was influenced by a general demand for meals that were tasty, satisfying and convenient( Reference Dunn, Mohr and Wilson 150 ). However, the assumption that individuals consider unhealthy foods, such as fast food, to be tasty has been challenged. A study in France reported that healthier foods were found to be tastier and more desirable due to a sense of increased quality when compared with unhealthier foods (Table 5)( Reference Werle, Trendel and Ardito 173 ). Thus, it would appear that taste is relatively subjective and may vary cross-culturally and between nations. That said, food manufacturers utilise cost-effective ingredients, such as salt, fat and sugar, to meet consumer demand and boost sales( Reference Glanz, Basil and Maibach 130 ). Food addiction studies have focused on palatable foods, such as fast foods, that contain fat, salt and sugar among other ingredients, which increase their desirability( Reference Garber and Lustig 171 ). The combination of these three ingredients are used to optimise palatability which is regularly referred to as the ‘bliss point’( Reference Moss 174 ). A study in Connecticut used a twenty-eight-item self-reported measure to assess food cravings, defined as ‘an intense desire to consume a particular food (or food type) that is difficult to resist’ (Table 5)( Reference Chao, Grilo and White 175 ). Results showed significant positive associations with having a higher BMI and craving high-fat foods (including fast food), carbohydrates/starches and sweets( Reference Chao, Grilo and White 175 ). Complementary to this research, Gearhardt et al. ( Reference Gearhardt, Rizk and Treat 176 ) reported that addictive-like eating increased craving for food in general but most of all for processed foods (Table 5). However, only overweight and obese women were included in the study and the results may not be representative of lean and normal-weight individuals. These studies highlight an association between being overweight or obese and experiencing food cravings or addictive-like eating patterns. That said, the entire concept of food addiction is not without debate. Corwin( Reference Corwin 177 ) argued that food addiction may not necessarily be a true phenomenon, partly because food is a necessity of life, but also due to the role of economic deprivation and food environments that are saturated with large numbers of takeaway and fast food outlets.

Study limitations

The majority of the literature on out-of-home foods was sourced from Australia, the USA and the UK, with some literature addressing the emerging phenomena of nutrition transition in low- and middle-income countries. This has restricted the comparability of the prevalence of out-of-home food consumption between countries, limiting our understanding of the implications of out-of-home food consumption in other parts of the world, outside the USA, Australia and the UK. Results are also limited to the cross-sectional design of the studies and longitudinal studies are warranted to confirm patterns of relationships found. The quality of some of the research is also challenged as a result of small sample sizes or unrepresentative populations (such as undergraduate students). Due to the wide scope of the present review, the lack of robust data and the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria of systematic reviews, including study populations, study design, comparison groups and measured outcomes, it is currently impossible to compare information systematically. With further future studies this may then be possible to allow a more representative survey of the research ‘landscape’.

Implications for policy and practice

There is currently much debate over the potential avenues for diet-related disease intervention and findings from the present review have highlighted some of the main factors influencing out-of-home food consumption, for instance, use of planning regulations to restrict the opening of new out-of-home food outlets in deprived areas to help individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Other potential interventions include fiscal policies (incentives and taxation); however, research suggests that taxation of fast food would adversely affect the poorest of Western societies( Reference Propper 178 ). This is evident as food insecurity is particularly widespread among deprived communities, with healthier food substitutes not always being readily available( Reference Cotti and Tefft 179 ). Despite these concerns, the lack of relevant literature on taxation in different populations indicates that the impact is relatively unknown( Reference Green, Cornelsen and Dangour 139 ). An alternative action would be to target those producing and selling out-of-home foods, with help and guidance for food product reformulation and labelling or ‘sign-posting’ of healthier food options( Reference Hillier-Brown, Summerbell and Moore 180 ). On a positive note, the WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2013–2020( 181 ) has aimed to reduce the impact of unhealthy diets through multisector action. The array of actions include reducing advertisement of unhealthy foods, promoting healthy foods by increasing accessibility and affordability, economic interventions, recipe reformulations to reduce sugars, salt and fats in processed foods, and improving food security( 181 ).

Conclusion

Food, whether out-of-home food or home-made meals, is linked to all aspects of life and most importantly health; thus the food consumed will either keep individuals in good health or increase pressure on already exhausted health systems. With obesity being endemic in many of the World’s countries, most notably those adopting modern ‘Westernised’ diets and lifestyles, it is suggested that today’s diet contains an overabundance of energy-dense foods. There is not one sole reason why people eat out-of-home foods and this narrative literature review presents some key factors that influence consumption, many of which are intertwined. Economic disadvantage in the food environment appears to be a strong determinant of access to out-of-home foods and consequent intake. However, further research is warranted to understand socio-economic differences between types and frequencies of out-of-home food intake. In addition, the biological and psychological drives combined with a culture where overweight and obesity are becoming the norm makes it ‘fashionable’ to consume out-of-home food. Further research to understand this complex interplay is essential. Lastly, there are a limited number of qualitative studies regarding out-of-home foods; therefore, extending previous research with more in depth studies may aid the understanding of the underlying reasons and motivations of out-of-home food consumption.

Overall, there is a strong warrant for further research into the out-of-home food phenomenon; to strengthen knowledge on the determinants of out-of-home food consumption within populations (and if this varies between countries); to assist the formation of a coherent body of evidence; and to support the development of effective interventions to reduce the impact of out-of-home foods on public health.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

The submitted article represents the original work of the authors. H. G. J. was responsible for researching, writing and preparing the manuscript. I. G. D., L. D. R. and L. S. provided intellectual input, proof reading and corrections.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.