No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

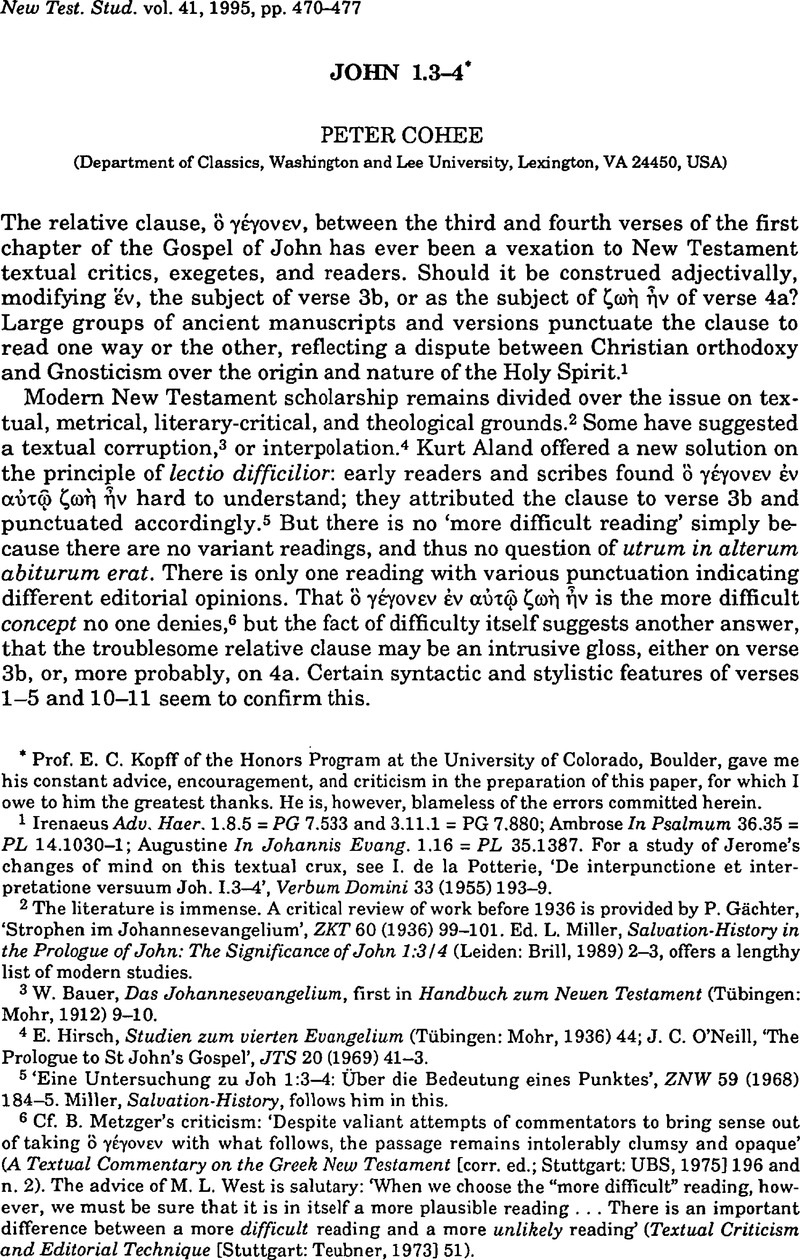

1 Irenaeus Adu. Haer. 1.8.5 = PG 7.533 and 3.11.1 = PG 7.880; Ambrose In Psalmum 36.35 = PL 14.1030–1; Augustine In Johannis Evang. 1.16 = PL 35.1387. For a study of Jerome's changes of mind on this textual crux, see Potterie, I. de la, ‘De interpunctione et inter-pretatione versuum Joh. 1.3–4’, Verbum Domini 33 (1955) 193–9.Google Scholar

2 The literature is immense. A critical review of work before 1936 is provided by Gächter, P., ‘Strophen im Johannesevangelium’, ZKT 60 (1936) 99–101Google Scholar. Ed. L., Miller, Salvation-History in the Prologue of John: The Significance of John 1:3/4 (Leiden: Brill, 1989) 2–3Google Scholar, offers a lengthy list of modern studies.

3 Bauer, W., Das Johannesevangelium, first in Handbuch zum Neuen Testament (Tübingen: Mohr, 1912) 9–10.Google Scholar

4 Hirsch, E., Studien zum vierten Evangelium (Tübingen: Mohr, 1936) 44Google Scholar; O'Neill, J. C., ‘The Prologue to St John's Gospel’, JTS 20 (1969) 41–3.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

5 ‘Eine Untersuchung zu Joh 1:3–4: Über die Bedeutung eines Punktes’, ZNW 59 (1968) 184–5Google Scholar. Miller, Salvation-History, follows him in this.

6 Cf. criticism, B. Metzger's: ‘:Despite valiant attempts of commentators to bring sense out of taking ό γέγονεν with what follows, the passage remains intolerably clumsy and opaque’ (A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament [corr. ed.; Stuttgart: UBS, 1975] 196Google Scholar and n. 2). The advice of West, M. L. is salutary: ‘When we choose the “more difficult’ reading, however, we must be sure that it is in itself a more plausible reading … There is an important difference between a more difficult reading and a more unlikely reading’ (Textual Criticism and Editorial Technique [Stuttgart: Teubner, 1973] 51).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

7 B 1 in Diels, H. and Kranz, W., Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker (5th ed.; Berlin: Weidmann, 1934)Google Scholar. And how very interesting that the subject, and in the proemium of this work, is an eternal Logos misunderstood by the World! This remarkable ‘Reminiszenz’, which Prof. John C. Gibert of the Department of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder, kindly brought to my attention, had been noted by Norden, E., Die antike Kunstprosa (2 vols.; Leipzig: Teubner, 1898) 2.472–3Google Scholar; cf. Bauer, Johannesevangelium, 11.

8 Cf. Norden, Kunstprosa, 1.36–7.

9 Schlügl, R., ‘Joh 1,1–18’, ZKT 35 (1911) 754Google Scholar; Bultmann, R., ‘Der religionsgeschichtliche Hintergrund des Prologs zum Johannesevangelium’, in: EYXAPΣITHPION. Studien zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments (ed. H., Schmidt; 2 vols.; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1923) 2.3–5Google Scholar; Gächter, ‘Strophen’, 102; M.Boismard, -E., ‘Le prologue de Saint Jean’, Lectio Divina 11 (1953) 103–4Google Scholar; Haenchen, E., 'Probleme des johanneischen “Prologs’’, ZTK 60 (1963) 308Google Scholar; Rissi, M., ‘Die Logoslieder im Prolog des vierten Evangeliums’, TZ 31 (1975) 321Google Scholar; Miller, Salvation-History, 5.

10 Käsemann, E., ‘Aufbau und Anliegen des johanneischen Prologs’, Libertas Christiana 26 (1957) 78Google Scholar; O'Neill, ‘Prologue’, 49.

11 ‘Ut ait Lucilius bonum schema est, quotiens sensus variatur in iteratione verborum, et in fine positus sequentis sit exordium, qui appellatur climax.’

12 Miller, Salvation-History, 4, 9,10.

13 Ibidem, 9–10.

14 Boismard, ‘Prologue’, 107.

15 J. Irigoin, ‘La composition rythmique du prologue de Jean (I, 1–18)’, RB 78 (1971) 506–7.

16 Athal, D., Structure et significance des cinq versets de I'hymne johannique au Logos (Louvain: Nauwelaerts, 1972) 30.Google Scholar

17 Kühner, R. and Gerth, B., Grammatik der griechischen Sprache (3rd ed.; Hannover/Leipzig: Hansche, 1904)Google Scholar II.2.248.4.

18 The opening words of which are noteworthy: ‘Ev αύτῶ γàρ ζμεν …!

19 Norden, Kunstprosa, 2.472.

20 Fifteen times in the Gospel alone: 5.30; 6.63; 8.15, 28; 9.33; 10.41; 11.49; 12.19; 14.30; 15.5; 16.23; 18.9, 20, 31; 21.3.

21 Blass, F. and Debrunner, A., A Greek Grammar of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago, 1961) §, 258Google Scholar. Cf. Smyth, H. W., Greek Grammar (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1956) § 1126 and § 1135.Google Scholar

22 Cf. Bauer, Johannesevangelium, 10.

23 This is tenuous, especially when we compare the three clauses of verse 1. But the word order seems to have a different purpose, as noted.

24 Metzger, Commentary, 196.

25 Ibidem.

26 Cf. Miller, Salvation-History, 45, 51.

27 Cf. Smyth, Greek Grammar, § 995.

28 Boismard, ‘Prologue’, 106–7.

29 Gächter, ‘Strophen’, 101; Irigoin, ‘Composition’, 504, 507–8.

30 Bauer, Johannesevangelium, 15; Käsemann, ‘Aufbau’, 81–2; Miller, Salvation-History, 6.

31 O'Neill, ‘Prologue’, 42.

32 West, Textual Criticism, 59: ‘sometimes one sees a conjecture dismissed simply on the ground that all the manuscripts agree in a different reading. As if they could not agree in a false reading, and as if it were not in the very nature of a conjecture that it departs from them!’ Cf. Metzger, Commentary, 217.

33 Aland, «Untersuchung’, 188–9; Miller, Salvation-History, 33–9.

34 ‘Untersuchung’, 188.

35 In Annuaire du Collège de France 87 (1986–1987) 611–12Google Scholar, a reference which I owe to the kindness of Prof. E. C. Kopff.

36 Salvation-History, 33–5.