6696 results in Middle East government, politics and policy

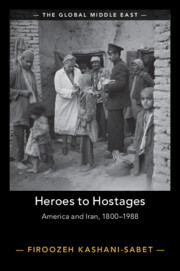

Heroes to Hostages

- America and Iran, 1800–1988

-

- Published online:

- 03 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 24 August 2023

Leaders in the Middle East and North Africa

- How Ideology Shapes Foreign Policy

-

- Published online:

- 03 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 17 August 2023

3 - Itineraries of Exile

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 70-96

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Figures

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp vi-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Feeling Palestine in South Africa

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 151-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion: The Way Home

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 219-228

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 229-251

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Jaffa: From the Blushing ‘Bride of Palestine’ to the Shamed ‘Mother of Strangers’

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 25-46

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - The Palestine of Tomorrow

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 183-218

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp v-v

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 252-259

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The ‘New Normal’

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 47-69

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Living in Memory: Exile and the Burden of the Future

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 97-117

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Who’s Afraid of the Right of Return?

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 1-24

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Broken Tiles and Phantom Houses: Urban Intervention in Tel Aviv-Jaffa Now

-

- Book:

- Displacement and Erasure in Palestine

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2023, pp 118-150

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Making Democracy Safe for Busines

- Published online:

- 22 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 06 July 2023, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Data Availability Statement

-

- Book:

- Making Democracy Safe for Busines

- Published online:

- 22 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 06 July 2023, pp xv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Case Study

-

- Book:

- Making Democracy Safe for Busines

- Published online:

- 22 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 06 July 2023, pp 77-107

-

- Chapter

- Export citation