6696 results in Middle East government, politics and policy

2 - “Mr. Security”

-

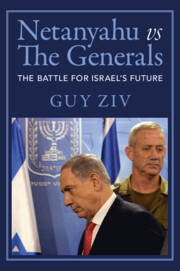

- Book:

- Netanyahu vs The Generals

- Published online:

- 11 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 51-87

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Netanyahu vs The Generals

- The Battle for Israel's Future

-

- Published online:

- 11 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024

5 - Stuck

- from Part II - Malta

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 119-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 188-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 168-175

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Moving On

- from Part II - Malta

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 149-167

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Libya

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 27-103

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Waiting

- from Part I - Libya

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 83-103

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Maps

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 176-187

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Detained

- from Part I - Libya

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 29-57

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Malta

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 117-167

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Staying On

- from Part I - Libya

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 58-82

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 1-26

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Turbulence at Sea

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 104-116

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Life Worlds of Middle Eastern Oil

- Histories and Ethnographies of Black Gold

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 20 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2023