Gram sabhas are open assemblies that constitute an integral part of a system of decentralized participatory local government in India. These talk-based, discursive public meetings are constitutionally mandated and have brought a form of direct democracy to Indian villages. They bear on the lives of 800 million people living in two million villages and are, in effect, the largest deliberative institution in human history. This book is a scholarly investigation into the gram sabhas’ potential for enhancing the capacity of ordinary citizens to engage with democracy under the enormously wide-ranging conditions and constraints that shape life in rural India. Our data are transcripts from 298 village assemblies from four neighboring South Indian states that were sampled and recorded within the framework of a natural experiment. And we use discourse analysis on this corpus of transcript data to gain insights into how India’s rural citizens engage with this form of direct democracy.

The 73rd amendment to the Indian constitution gives gram sabhas the power to discuss and legislatively intervene in many important decisions within the ambit of the gram panchayat, or village local government.Footnote 1 Within gram sabhas’ purview come such issues as the selection of beneficiaries for public programs, the allocation and monitoring of village budgets, and the selection of public goods such as roads, drains, and common property resources. Higher-level governments make use of them as a forum to announce new policy initiatives and public health alerts. Open to the public and focused on village development and governance, these meetings allow citizens to bring up a wide range of concerns from garbage collection to corruption. They provide a significant participatory space for community action and for political posturing and campaigning.

Rural India is far from an ideal site for deliberation. There are persistent economic inequalities and deep social cleavages linked to a highly stratified caste-based social structure. Acute gender inequality exists amidst high levels of poverty. Stark deprivations prevent the fulfillment of basic needs. These deficits are accompanied and aggravated by the problem of illiteracy. All these problems have made Indian democracy seem a puzzle to many observers. Unsurprisingly, a large body of literature has sought to understand why electoral democracy has thrived in India (e.g. Khilnani Reference Khilnani1999; Kaviraj Reference Kaviraj2011; Keane Reference Keane2009; Chatterjee and Katznelson Reference Chatterjee and Katznelson2012). Our book attempts to understand how this context shapes the deliberative, talk-based form of direct democracy in village assemblies.

Electoral democracy is based on the simple but elegant notion that tallying votes aggregates preferences. It is assumed that the political candidate elected by popular vote to represent a diverse set of citizens will also give representation to their collective interests. The limitations of this mechanism as a way of governing large, complex societies have increasingly become apparent throughout the world with challenges that range from elite capture (e.g. Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010), clientelism (Bardhan and Mookherjee Reference Bardhan and Mookherjee2016), and legitimation (e.g. Keane Reference Keane2009). This has led to a revival of the very old idea of direct democracy – that interests of diverse citizens can be represented by a process of discussion, debate, and dialogue that builds consensus. This form of deliberative democracy derives from the premise that “democracy revolves around transformation rather than simply the aggregation of preferences” (Elster Reference Elster1998).

As several scholars have pointed out (e.g. Mansuri and Rao Reference Mansuri and Rao2012), deliberation is not just a Western idea. It has formed the basis of decision-making throughout history in many different times and cultures. Recent discussions of democratic political deliberation, drawing largely on John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas, see it as ideally rooted in equality, rationality, and the free exchange of thoughtful argumentation of ideas. Deliberation, according to this understanding, is a mechanism for resolving reasonable differences within a pluralistic society. These theories assume three necessary preconditions for deliberation: first, parties in deliberation are formally and substantively equal; second, deliberation is based on reason rather than coercion, such that “no force except that of the better argument is exercised” (Habermas Reference Habermas1975, p. 108); third, the focus of deliberation should be the common good rather than the pursuit of individual interests. Public concerns, in other words, should prevail over private interests.

These stringent formal requirements have been questioned, refined, and extended in a variety of ways in the recent surge of scholarly interest in deliberative democracy. This literature has been primarily normative, with an emphasis on theory-building and institutional design (e.g. Bohman and Rehg Reference Bohman and Rehg1997; Dryzek 2002; Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson1996; Goodin Reference Goodin2003; Parkinson and Mansbridge Reference Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). It tends to focus on specifying the conditions under which deliberative democracy is likely to function, outlining variations in deliberative modalities, and emphasizing its many positive consequences for participants.

There are a few detailed empirical studies of deliberative democracy drawing on examples from Western democracies. These studies include Mansbridge’s (Reference Mansbridge1980) on town meetings in New England, Fung’s (Reference Fung2004) on neighborhood governance in Chicago’s South Side, Polletta’s (Reference Polletta2004 and Reference Polletta2006) on deliberative spaces in the United States (including online forums), and Steiner et al.’s (Reference Steiner, Bächtinger, Spörndli and Steenbergen2005) quantitative examination of parliamentary deliberation. There is also a growing empirical literature on deliberation in the developing world (Heller and Rao Reference Heller and Rao2015). There is work on gram sabhas, which we review later in this chapter, and extensive research on participatory budgeting.Footnote 2 Of particular relevance to this book is Baiochhi, Heller, and Silva’s (Reference Baiocchi, Heller and Silva2011) work using a similar sample-matching methodology that examines the impact of participatory budgeting in eight Brazilian cities. There is also Barron, Diprose, and Woolcock’s (Reference Barron, Diprose and Woolcock2011) book on an Indonesian project that used deliberative forums to resolve conflicts and build the “capacity to engage.” Apart from these studies, this literature is largely focused on ad hoc groups and meetings that are not institutionalized (Mansuri and Rao Reference Mansuri and Rao2012).

Our book analyzes discourses in the gram sabha, focusing on discussions, dialogues, and speeches. It provides insight into how the imbricated inequalities that mark everyday life shape the reach and contribution made by this deliberative form of direct democracy in rural India. Discourse analysis of the gram sabha allows us to revisit the normative claims underlying studies of deliberative democracy in a radically different context. This raises several important questions, including the role that political models based on deliberative democracy can play in social and communicative contexts of contemporary India, and in other non-Western contexts, that vary so greatly from those assumed by normative theorists of deliberative democracy.

How are we to understand the empirical reality of gram sabhas? Is equality a necessary precondition for deliberation? Can deliberation help nudge communities toward becoming better collective actors and encourage discursive equality? Can the existence of regularly scheduled and constitutionally empowered public forums create an effective public sphere? What role should the state play in influencing and facilitating these forums? What do villagers talk about and what impact does that talk have on turning villagers into citizens of a democratic polity? How are we to understand public discussions of governance and development engaged in by citizens who cannot read or write? What difference does literacy make for democratic deliberation? Does deliberation in non-Western contexts require a rethinking of democratic theory? How should we characterize the interaction between political and civil society in non-Western and poorer democracies, such as India?

Partha Chatterjee has influentially argued that the mass of India is better conceptualized as “political society” rather than “civil society.” Political society is seen (following Foucault) as a governed “population” – “differentiated but classifiable, describable, and enumerable.” Politics are seen as “a set of rationally manipulable instruments” for reaching large sections of the inhabitants of a country as the “targets of policy” (2001,173).Footnote 3 And although political society has voting rights and relishes and exercises those rights in high proportions, nevertheless, voting is viewed as the exercise of agency within a context of political manipulation and constrained choices. Civil society, on the other hand, according to Chatterjee, is reserved for a more privileged set of rights and freedoms and implies an active associational life in which free and equal citizens participate and deliberate at will. He argues that in India, unlike the West, “this is restricted to a fairly small section of ‘citizens’ – urban, educated, elites” (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee, Kaviraj and Khilnani2001, 172).

The gram sabha does not fit easily within this binary classification as either an instrument for administering a mass, “manipulable,” poor, political society or as an associational institution expressing the will of autonomous, formally equal citizens exercising rights within a robust civil society. At one level the gram sabha is an archetypical extension of political society. Benefits granted by the state are doled out via processes of Cartesian commensuration to people it categorizes as below the poverty line (BPL). This status is determined by strict quantitative measurement and targeting. Nevertheless, by creating a space for the rural poor to speak within a relatively equal discursive playing field, the gram sabha allows people to question and critique political elites on issues ranging from policy choices to policy implementation and corruption. It allows villagers to critique the rules of commensuration used by the state to define a deserving beneficiary, to make dignity claims, and to forge and carry out concrete democratic civic actions.

In this sense then, gram sabhas are an example of state engineering by the federal government to create the infrastructure of democracy through which to facilitate “induced participation” (Mansuri and Rao Reference Mansuri and Rao2012). The effect however approximates some of the features and benefits associated with civil society. Gram sabhas are an attempt to create “invited spaces” (Brock et al. Reference Brock, Cornwall and Gaventa2001) for deliberative participation within a formal, constitutionalized system of local government. They do not fit well within Chatterjee’s vision of India as a polity sharply split between political and civil society.

Deliberative institutions, like the gram sabha, are becoming increasingly important in the world as forums to allocate resources to the poor (Mansuri and Rao, Reference Mansuri and Rao2012). By moving decision-making power from government bureaucracies to villages and neighborhoods, these institutions have been viewed as a way to wrest power from elites. They are ways of making the implementation of development interventions more efficient and improving the equity and transparency of allocations. “Citizen engagement” of this kind is seen as the key to accountability. This has led to a vast literature scrutinizing government accountability. Scaling up such deliberative systems effectively remains a challenge however (Fox Reference Fox2016). Systems that work in a few villages or neighborhoods often do not work as hoped when they are expanded to entire countries (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1967; Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Pritchett and Woolcock2013; Majumdar et al. Reference Majumdar, Rao and Sanyal2017). Gram sabhas, because they are mandated by the constitution and are institutionalized, already function at a huge scale. They provide an ideal ground for understanding the challenges of setting up systems of citizen engagement across entire societies and countries.

In this book we study the quality of discourse and not the impact of deliberative processes on “hard outcomes,” such as better quality or delivery of public goods or lowering corruption. It is important to note that there is a growing body of evidence that shows that when institutions for “social accountability” and citizen engagement are effectively developed and nurtured with government commitment, they can have tangible effects on hard outcomes (Mansuri and Rao Reference Mansuri and Rao2012; Fox Reference Fox2015). This is also true of the villages analyzed in this book. In an econometric analysis of 5,180 randomly chosen households from a subset of the same villages we analyze, Besley, Pande, and Rao (Reference Besley, Pande and Rao2005) find that when gram sabhas are held governance sharply improves. Focusing on a specific policy administered at the local level (access to a BPL card, which provides an array of public benefits), they find that policies were more effectively targeted to landless and illiterate individuals when a gram sabha was held. Effects were large, raising the probability of receiving a BPL card by 25 percent. The reason gram sabhas result in better identification of poor families is related to one of their primary roles in village government. BPL lists are first determined on the basis of a survey conducted by the government that identifies poor households using a given set of criteria. In many states, however, the lists of beneficiaries identified as meeting these criteria have to be ratified by the gram sabha. This allows for public verification of the people included on the list. It also provides villagers an opportunity to point out wrongful inclusions and unjust exclusions as well as scope for questioning and critiquing the government’s definition of poverty.

Valuing such systems of democratic engagement and participation accords with the holistic view of “development as freedom” championed by Amartya Sen (Reference Sen1999). His vision marks a shift from a traditional preoccupation with economic growth, outcomes, and instrumental ends and calls for an increased sensitivity to human agency, capabilities, and associational freedoms (Heller and Rao Reference Heller and Rao2015). For all these reasons, it is important to train our lens on the discursive landscape of gram sabhas. In this book, accordingly, we engage in a talk-centered analysis aimed at understanding how ordinary citizens and villagers interact and engage with the state, focusing on what is discussed in these assemblies, what ordinary citizens say, and how they say it. We also analyze how state actions influence the discursive vitality and scope of gram sabhas.

A Brief History of the Gram SabhaFootnote 4

Early History

While Indian electoral democracy was only instituted in the first half of the twentieth century, the practice of public reasoning and deliberation is a much older phenomenon, dating back to Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions from as early as the fifth century BCE. Religious councils hosted by early Indian Buddhists, for example, often focused on resolving debates within and across religious traditions. Importantly, they “also addressed the demands of social and civic duties, and furthermore helped, in a general way, to consolidate and promote the tradition of open discussion on contentious issues” (Sen Reference Sen2005, p. 15). In the third century BCE, such practices became celebrated under the reign of Ashoka, who sought to codify rules for public discussion that emphasized mutual respect and honor (Lahiri Reference Lahiri2015). By the sixteenth century, under the reign of Akbar, interfaith dialogues were explicitly aimed at the pursuit of reason rather than reliance on tradition. The priority given to equality and reason in deliberation echoes standards in contemporary deliberative theory. Perhaps even more significantly, their explicit sponsorship by the state reveals the extent of such deliberative councils’ structural importance in ancient and medieval India.

Even in this early period, participants in such public debates extended beyond the intellectual, political, and religious elites. Early debates – in sabhas, panchayats, and samajs – often included both notable big men and peasants, in contestation with each other and in opposition to the state. Indeed, “the term sabha (association) itself originally indicated a meeting in which different qualities of people and opinions were tested, rather than the scene of a pronunciamento by caste elders” (Bayly Reference Bayly1996, p. 187). Of course, the inclusiveness and accessibility of such public debates should not be overstated. Like other emergent public spheres, India’s growing deliberative institutions were uneven in their reach and were still predominantly the province of the educated. Despite their limited scope, however, the presence of a bounded, but critical public sphere suggests an important foundation for future participatory and democratic politics.

By the late nineteenth century, Western liberal philosophers had begun to articulate a vision of participatory democracy in which equal citizens could collectively make decisions in a deliberative and rational manner. These ideas would profoundly shape, and be shaped by, the British presence in India. Of particular relevance for the trajectory of Indian deliberation was Henry Maine, who was sent to India in the 1860s to advise the British government on legal matters. While serving in the subcontinent, he came across several accounts by British administrators of thriving indigenous systems of autonomous village governments, whose structure and practice shared many characteristics of participatory democracy (Maine Reference Maine1876). Maine had been influenced by J. S. Mill, who argued that universal suffrage and participation in a democratic nation would greatly benefit from the experience of such participation at the local level (Mill Reference Mill1860). Observing Indian village governments, Maine came to articulate a theory of the village community as an alternative to the centralized state. These village communities, led by a council of elders, were not subject to a set of laws articulated from above, but had more fluid legal and governance structures that adapted to changing conditions, while maintaining strict adherence to traditional customs (Mantena Reference Mantena2010).

This argument had an impact on colonial administration. As India became fertile territory for experiments in governance, the liberal British Viceroy Lord Ripon instituted local government reforms in 1882 for the primary purpose of providing “political education,” and reviving and extending India’s indigenous system of government (Tinker Reference Tinker1954). The implementation of these reforms followed an erratic path, but an Act passed in 1920 set up the first formal, democratically elected village councils, with provinces varying widely in how councils were constituted, in the extent of their jurisdiction, and in how elections were held (Tinker Reference Tinker1954).

Beyond influencing colonial policy, Maine’s description of self-reliant Indian village communities came to shape the thinking of Mohandas Gandhi, who made it a central tenet of his vision for an independent India (Rudolph and Rudolph Reference Rudolph and Rudolph2006; Mantena Reference Mantena2012). Gandhi’s philosophy of decentralized economic and political power, as articulated in his book Village Swaraj, viewed the self-reliant village as emblematic of a “perfect democracy,” ensuring equality across castes and religions and self-sufficiency in all needs. These villages would come to form “an alternative panchayat raj, understood as a nonhierarchical, decentralized polity of loosely federated village associations and powers” (Mantena Reference Mantena2012, p. 536). Stressing nonviolence and cooperation, this Gandhian ideal elevated local participation to being not just for the sake of the political education of India’s new citizens but a general form of democratic self-governance.

Gandhi’s proposal, however, was defeated during the Constituent Assembly Debates. B. R. Ambedkar, the principal architect of the constitution and a fierce advocate for the rights of Dalits (formerly known as “untouchables” and classified by the government as Scheduled Castes), was deeply skeptical of village democracy. Arguing against it he proposed, “What is the village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism?” (Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr2015, p. 86). Ambedkar’s insistence on recognizing the realities of entrenched social and economic inequality severely limited his belief in the possibility of a robust, participatory democracy in India. He suggested that India would enter democracy as a “life of contradictions,” in which political equality would be in continuous conflict with persistent social and economic inequality. This animated his principled arguments that the constitution should guarantee more than just formal equality through the vote. He demanded that the constitution play a major role in the nation’s development by including the guarantee of education and employment, the abolition of caste and other social ills, and the provision of certain forms of group representation.

Village democracy did not entirely disappear from the Indian constitution, however. Article 40 stated that “the State shall take steps to organize village panchayats and endow them with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as units of self-government.” Though this article was a mere “directive principle,” or non-judiciable guidepost for policy, some state governments did set up formally constituted village democracies. In 1947, India’s largest state, Uttar Pradesh, pioneered the approach of instituting a deliberative body that it called a gaon sabha, which met twice a year to discuss and prioritize the concerns of the village (Retzlaff Reference Retzlaff1962.

By the 1950s a confluence of domestic and international factors led to a renewal of calls for citizens having greater voice in their communities’ development (Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr2015). India became a particularly fertile ground for such policies, which led a renewed call to strengthen village democracy. A government committee, led by a senior politician, Balwantray Mehta, was formed to spearhead the initiative. It released a report in 1957 that set the foundation of Panchayati Raj, a government-led plan to decentralize democracy into three tiers of local government empowered to direct the local development agenda (Mehta Reference Mehta1957).

Deliberation under Panchayati Raj

As states came to adopt the panchayati structure, most were far from realizing the Gandhian ideal of egalitarian self-governance. Deliberation and participation under this new structure was meant to elicit the “felt needs” of the village, which depended on the ability of the village to be a cohesive body that was capable of articulating a general will. In practice “the tendency of the spokesmen for the village to come from the powerful, landed classes within rural life was widely acknowledged,” and any “actual felt needs that threatened village solidarity – such as a desire for land reform, the abolition of caste hierarchies, or sexual equality – were quickly ruled out” (Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr2015, p. 92). Even S. K. Dey, the first Union Cabinet Minister for Cooperation and Panchayati Raj, admitted that many villages had nominal success, with paper forms completed but no actual programs implemented (Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr2015, p. 94). The gradual adoption of panchayat implementation proceeded unevenly across the country, with more success in some states than others.

The modern gram sabha was pioneered by the government of Karnataka, which passed an act in 1985 establishing democratically elected mandal panchayats (a mandal consisted of several villages), with clearly delineated functions and appropriate budgets. Gram sabhas played a central role in the Karnataka mandal panchayat system. All eligible voters in a mandal were members of the sabha, which would be held twice a year. The sabhas were tasked with discussing and reviewing all development problems and programs in the village, selecting beneficiaries for anti-poverty programs, and developing annual plans for the village (Aziz Reference Aziz, Singh and Sharma2007). In practice, the sabhas were resented by village councilors because they were subject to queries and demands for explanations from citizens. Their answers often elicited heated reactions. Gram sabhas were largely abandoned after the first year of the implementation of the 1985 act. If the meetings were held, they were conducted without prior announcement or were held in the mandal office, which could not accommodate more than a few people (Crook and Manor Reference Crook and Manor1998).

Despite this, the Karnataka reforms were seen as an important innovation in village government and received wide support across the political spectrum. A movement to amend the Indian constitution to strengthen Article 40 with tenets drawn from the Karnataka Act gained momentum. This resulted, in 1992, in the passage of the 73rd constitutional amendment, which gave several important powers and functions to village governments. The three-tier system of decentralization and its accompanying forum for deliberation, the gram sabha, were formally codified. It mandated that all Indian villages would be governed by an “executive” elected village council, the gram panchayat,Footnote 5 and there would be a “legislature” formed by the gram sabha, an assembly of all citizens of the village, that would hold public meetings at least two times a year. Lastly, the amendment required that at least 33 percent of seats in village councils would be reserved for women, and seats would also be reserved for disadvantaged castes by a number proportionate to their population in the village.

Following the passage of this amendment, Kerala, India’s most literate state, which had a long history of progressive politics, initiated a radical program of participatory decentralization (Isaac and Franke Reference Isaac and Franke2002), where the gram sabha played a central role. The program rested on three pillars. It devolved 40 percent of the state’s development budget to village panchayats, gave substantial powers to these councils, and instituted a People’s Campaign. This was a grassroots program to raise awareness, train citizens to exercise their rights, and help them become active participants in the panchayat process. The latter goal was to be achieved primarily by participating in gram sabhas.

Gram sabhas have become central to Kerala’s village planning process, which is based on a set of nested piecemeal stages (Isaac and Heller Reference Isaac, Heller, Fung and Wright2003). Working committees and “development seminars” are held in conjunction with gram sabhas to make them practical spaces of deliberative decision-making and planning. Instead of open deliberation, attendees are divided into resource-themed groups or committees. The discussions within each group yield consensual decisions regarding the designated resource. This structure is geared toward increasing the efficiency of consensual decision-making. And it is facilitated by various training programs to instruct citizens on deliberative planning as well as local bureaucrats on methods for turning plans into effective public action.

Heller, Harilal, and Chaudhuri (Reference Heller, Harilal and Chaudhuri2007) have studied the impact of the People’s Campaign in Kerala with qualitative and quantitative data from 72 gram sabhas. They have found that the campaign has been effective, with positive effects on the social inclusion of lower-caste groups and women in decision-making. Gibson (Reference Gibson2012), examining the same data, has argued that the key explanation for the effectiveness of gram sabhas in Kerala is the high level of participation by women. Over the last two decades all other Indian states have implemented the various tenets of the 73rd amendment. They have done so with varying levels of intensity and commitment. None has done so as effectively as Kerala.

Gram sabhas are thus deliberative forums embedded within an electoral system. The gram panchayat or village council and its leadership is elected every six years and gram sabhas are held either two or four times a year, depending on the state. In these forums citizens engage with elected officials and local bureaucrats. The politicians who participate are acutely aware that they are interacting with potential voters who have the power to reelect them or vote them out of office. This creates a relatively egalitarian discursive space (Rao and Sanyal Reference Rao and Sanyal2010). Low-caste citizens, who may hesitate to say some things in social settings, are less hesitant to say them in the gram sabha knowing that they are engaging in a kind of political performance. Politicians, in their turn, engage in a different kind of political performance in which they try to appear to be responsive to citizens, and try to avoid expressing the kind of quotidian prejudice that would turn away potential voters. Gram sabhas are now a permanent feature of the political landscape. The crucial question remains whether these egalitarian performances will become normalized over time to create an effective democratic space for deliberation and accountability.

Scholarly Work on the Gram Sabha

The effects of several aspects of the decentralization amendment (including the strength of electoral democracy, the impact of quotas for women and lower castes, and the implications of elections for distributive politics and clientelism) have been the subject of a large body of research (e.g. Chattopadhyay and Duflo Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004; Besley et al. Reference Besley, Pande, Rahman and Rao2004, Reference Besley, Pande and Rao2005; Bardhan and Mookherjee Reference Bardhan and Mookherjee2006; Beaman et al. Reference Beaman, Chattopadhyay, Duflo, Pande and Topalova2009; Ban and Rao Reference Ban and Rao2008; Chauchard Reference Chauchard2017). A small and growing body of scholarship has examined the sabha itself, and whether it serves as a mere “talking shop,” or constitutes a true deliberative forum in which citizens are able to raise and resolve issues of public relevance.

In previous work (Rao and Sanyal Reference Rao and Sanyal2010), using the same transcripts that we use in this book, we have found that participation in the gram sabhas acts as a vehicle for creating a shared, intersubjective understanding of what it means to be poor. We highlighted how lower-caste villagers use the discursive space of the gram sabha to transgress social norms and make claims for dignity. We showed how marginal groups use the gram sabha to voice their concerns, and how, through them, previously “hidden transcripts” became public and forced public discussion to take place on sensitive social issues that many would rather have avoided.

Our and others’ research has also shown that gram sabha deliberations often deviate from the ideal of rational argumentation. Sanyal’s (Reference Sanyal, Heller and Rao2015) work has highlighted citizens’ displays of emotions in gram sabha discussions and pointed to the mixed role of emotions – their constructive role as enforcers of accountability and justice and their negative role as cognitive impediments that can disrupt gram sabhas and hamper their ability to arrive at rationally actionable collective decisions.

Public discussions of common issues at the gram sabha are most effective when citizens are well informed and can demand accountability from public officials. Limited information and media coverage, however, often leave citizens at a “disadvantage when negotiating with local governments” (Bhattacharjee and Chattopadhyay Reference Bhattacharjee and Chattopadhyay2011, p. 46). Analyzing transcripts from gram sabhas in West Bengal, Bhattacharjee and Chattopadhyay find that villagers try to use information from media to negotiate with elected officials and inquire about entitlements. These requests, however, are easily ignored or dismissed by gram panchayat members, who can evade requests by claiming that the media is misleading audiences or is uninformed. The authors attribute this to the “thinness” of news coverage, which does little to empower citizens to confront officials. Despite this troubling picture, the authors acknowledge that the very act of demanding entitlements, even seemingly small and selfish claims for rice or pensions, reflects citizens’ “capacity to aspire” for a better life (Appadurai Reference Appadurai, Rao and Walton2004).

The low-literacy and high-inequality contexts in which deliberation within gram sabhas usually takes place raise the possibility that they are simply “talking shops” that bear no relationship to democratic dialogue. This hypothesis is explicitly tested by Ban, Jha, and Rao’s (Reference Ban, Jha and Rao2012) quantitative analysis of coded versions of the same gram sabha transcripts studied here. Deriving hypotheses from rational choice models of group decision-making under uncertainty, that work analyzed the transcript data to test three competing hypotheses concerning the types of equilibrium that characterize gram sabha interactions: (a) “cheap talk,” in which discussions are not substantive even though they may appear equitable; (b) elite capture, in which discussion is dominated by the interests of landowning and wealthy citizens; and (c) “efficient democracy,” in which meetings follow patterns of good democratic practice. This study found that in villages with more diversity in caste groups, and less village-wide agreement on policy priorities, the topics discussed track those of interest to the median household. In villages with less caste heterogeneity, the priorities of landowners are more likely to dominate the discourse (consistent with elite domination). The study concluded that gram sabhas are much more than mere opportunities for cheap talk. Rather, they closely follow patterns observed in a well-functioning “efficient” democracy.

Scholars have begun to examine whether deliberation in gram sabhas is gendered in nature, and how policies aimed at inclusion might mitigate gender biases. Sanyal, Rao, and Prabhakar (Reference Sanyal, Rao and Prabhakar2015) examine the differences in speech employed in the gram sabha by women who identify as belonging to self-help groups (SHGs) and women who do not (and likely do not belong to SHGs). They have found that women SHG members possess more “oratory competency.” This question is further explored in two recent working papers by Parthasarathy et al. (Reference Parthasarathy, Rao and Palaniswamy2017) and Palaniswamy et al. (Reference Palaniswamy, Parthasarathy and Rao2017). These authors use text-as-data methods on an original sample of transcripts from Tamil Nadu to evaluate whether and how women participate in village assemblies. They have found that despite the relatively high rates of attendance, women speak much less than men. They also show that a state intervention that builds women’s networks and trains them to engage with village government dramatically increases both women’s presence and frequency of speech at the sabha. Though the authors are optimistic about the potential of such policies to make deliberative spaces more inclusive, they also caution that the intervention shifts the topic of conversation toward the program itself, potentially crowding out organic demands and requests.

This book contributes to the literature by conducting a large-N discourse analysis of 298 transcripts of village assemblies from four neighboring states in Southern India recorded between 2003–2004: Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. It studies the nature of speech, how “voice” and collective discussions are expressed, the uses to which citizens put the gram sabha, and how agents of the state react to the concerns expressed in these village assemblies. It also employs a unique natural experiment to determine if deliberative spaces can be influenced and structured by state policy. Finally, it asks the crucial questions of how illiteracy affects the quality of deliberation and whether literacy is a precondition for effective deliberation.

Methodology

The Natural Experiment

Our choice of villages where we recorded the gram sabhas was guided by a natural experiment. We discuss the findings from this in Chapters 3 and 4. The experiment was to match similar villages on either side of modern state borders that share administrative histories, speak a common mother tongue, and have similar social structures. We assumed that given these shared sociolinguistic characteristics, discourse within them would be less affected by linguistic differences or differences in social structure and culture than by state policy and the underlying political economy of the state. Our sampling design of matching similar villages occupying different sides of state borders, therefore, allowed us to investigate and highlight the extent to which state policy can shape the nature of discourse in deliberative forums.

Method of Matching on Administrative History and Common Language

The map of British India was stitched together from the remnants of the Mughal Empire. After Mughal dominance over the subcontinent disintegrated over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Hindu and Muslim generals, courtiers, local chieftains, and sundry other powerful figures started exercising dominance over territory. Gradually these actors carved out autonomous kingdoms. The British East India Company entered India in the sixteenth century initially for the purpose of trade. In the process of establishing trade routes and consolidating trade monopolies, they gradually began to extend control over territory through treaties and armed force. Depending upon the relations of power and the local political situation in various places, territory came to be directly governed by the Crown, gradually extending to large states that were known as “presidencies.” In other places, indigenous rulers were installed and endowed with large incomes and some local autonomy. These “princely states” were indirectly controlled by British “residents.”

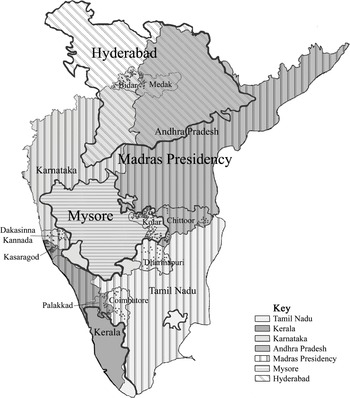

The shape of these territories closely reflected their historical antecedents. In Southern India, the state of Hyderabad was ruled by a Nizam, the first of whom was a Mughal governor who had seized control from its erstwhile suzerains over a large portion of the empire’s territory in the Deccan plateau. The state of Mysore was constructed in the early nineteenth century from the remnants of the kingdom of Tipu Sultan. Tipu’s reign was characterized by creative and successful resistance to British rule until successive defeats in the Third (1792) and Fourth Mysore Wars (1799). These were among the most decisive battles in the history of British colonial expansion. Part of Tipu’s empire was carved into Mysore state, and a member of the Wodeyar family (considered to be descended from the original Hindu rulers of the state) was installed on the throne. Much of the rest of South India became the Madras “presidency” under direct British rule. It was cobbled together by gradual expansion from its capital, the port city, from which the region then took its name.

Indian independence in 1947 brought with it a number of social movements that promoted unified linguistic identities for states. And a number of leading Indian politicians and intellectuals were advocating that Indian states be reorganized along linguistic lines in the belief that they could then be more rationally governed. A commission was instituted to undertake the painstaking process of meticulously examining historical antecedents and census data. The task was to solve the jigsaw puzzle of putting together new, linguistically unified states by merging districts that had the same majority language. The commission’s report was published in 1955 and its recommendations implemented in 1956. In the South, this led to the creation of four states – Andhra Pradesh (AP), largely Telugu speaking; Tamil Nadu (TN), Tamil speaking; Karnataka (KA), Kannada speaking; and Kerala (KE), Malayalam speaking. AP was pieced together from Hyderabad and the Telugu speaking parts of the Madras presidency.Footnote 6 Karnataka was carved out by merging the erstwhile princely state of Mysore with Kannada speaking parts of Hyderabad, and the Madras and Bombay presidencies. Kerala was formed by merging the princely states of Travancore and Cochin with parts of the Madras presidency. The rest of the Tamil speaking areas of Madras presidency became Tamil Nadu.

The States Reorganization Commission’s report (Govt. of India, 1955) details the process by which decisions were made to assign particular districts to particular states. The primary consideration was the language spoken by a majority of its residents. But this was coupled with sensitivity to fair assignments of economically valuable cities and ports, and with some sense of whether the merger made historical and cultural sense. The imperfections in this process are particularly apparent along the borders of the new states that were invariably multilingual, often with a mixed linguistic culture or identity. It is in the midst of these inevitable “mistakes” to be found on either side of the borders of the modern South Indian states where we focus our attention.

The way the borders of the modern South Indian states were overlaid upon the old political configurations can be seen in Map 1. Along the redrawn state borders there are districts that belonged to the same political entity prior to 1956 but were assigned by the Commission to different states. The villages along the modern border share a common history, having been part of the same political and administrative entity for over two hundred years. Following Bayly (Reference Susan1999) and Dirks (Reference Dirks2002), we argue that shared administrative and political histories should have caused the social structures of these divided districts to be similar. After all, until 1956, the villages had shared a common history of land tenure (closely related to caste (Kumar Reference Kumar1962, Reference Kumar1992)), administration, and reform, dating as far back as the Mughal period at least.

The villages in our sample are located on the borders of linguistically defined states. There is therefore considerable overlap among the languages spoken in villages along the border areas of these states. We selected blocks (subdistrict-level entities that are approximately equivalent to counties) on either side of the border matched by the mother tongue of the majority of people in each block. Within these matched blocks, we compared differences among villages across the border.

The core idea behind the natural experiment is made immediately evident by looking at Map 1. The Madras presidency and Hyderabad state are the two old administrative units that are relevant for our analysis. Within these old states we picked eight matched districts that were later split into different states after the reorganization. These four pairs are Bidar and Medak in Hyderabad, Dharmapuri and Chittoor, Kasaragod and Dakshina Kanada, and Coimbatore and Pallakad in different parts of the Madras presidency. Bidar and Dakshina Kanada are now in the state of Karnataka. Medak and Chittoor were in erstwhile AP. Dharmapuri and Coimbatore are in Tamil Nadu. And Pallakad and Kasaragod are in Kerala.

Within these districts we picked a set of blocks using the language matching strategy, and then a set of villages, randomly selected within each block, which were also matched by language. Details about the sampling and matching process follow. Our sampling was designed so that we could reasonably expect that discourse would be similar unless it has been shaped by state policy.

Sampling

In order to select the blocks within these districts that were best matched on language, we computed the linguistic distanceFootnote 7 for all combinations of blocks in each district pair. To choose the best matched block pairs we ranked all the pairs and selected the top ranked pairs, stopping when we found three (two for the Kerala–Tamil Nadu border) unique block pairs for each district pair.

The blocks were divided into several gram panchayats (GPs), each of which consisted of between 1 and 6 villages depending on the state. From each sampled block, in the states of AP, KA, and TN, we randomly sampled 6 GPs in every block. In Kerala the population per GP is roughly double that in the other three states. For this reason, in Kerala, we sampled 3 GPs in every block. This procedure gave us a total of 201 GPs. The complete sample has been used for other analyses (e.g. Besley et al. Reference Besley, Pande, Rahman and Rao2004), but for the purposes of this study we removed Kolar district because it was not matched historically to any of our other districts.

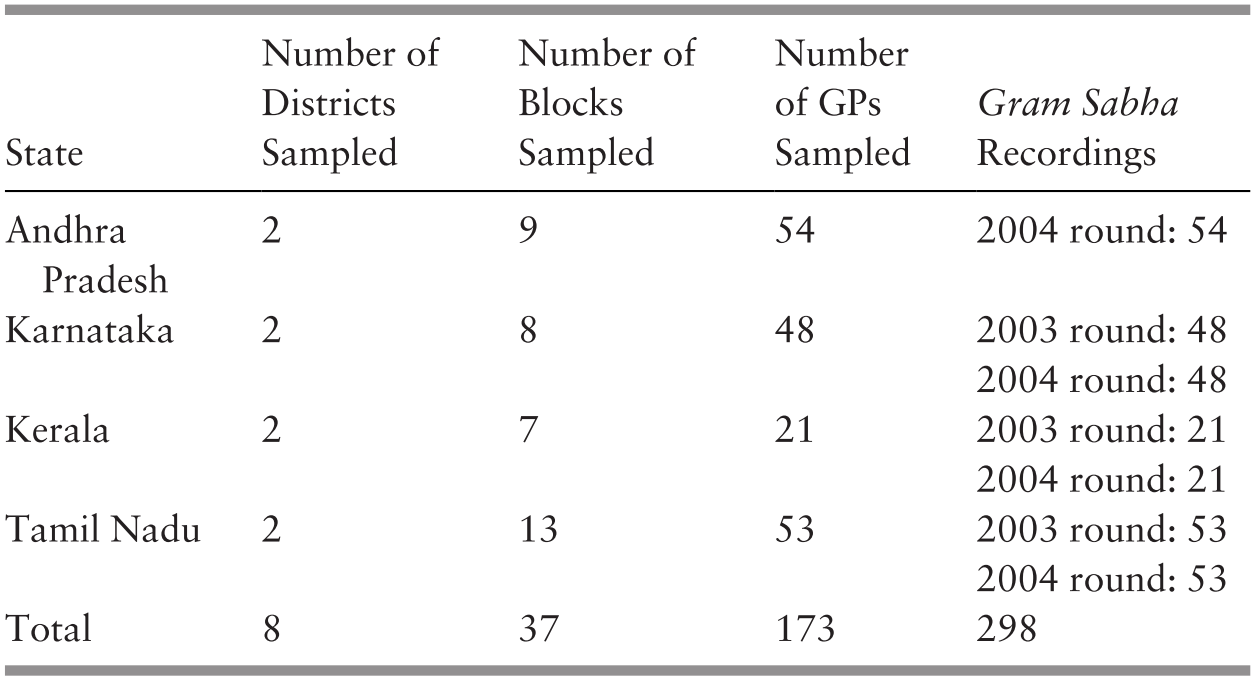

The blocks were divided into several GPs, each of which consisted of between 1 and 6 villages depending on the state. We conducted gram sabha recordings over two rounds in 2003 and 2004. Due to budgetary limitations we omitted recording gram sabhas in Andhra Pradesh in round 1. In round 1, in the other three states, we randomly selected 48 GPs from Karnataka, 21 wards from Kerala, and 53 GPs from Tamil Nadu, resulting in a total gram sabha sample from these three states of 122. In round 2 we expanded the sample to include the state of Andhra Pradesh, where we visited 54 randomly chosen GPs in 9 blocks. Table 1.1 provides a breakdown of the gram sabha sample by state, district block, and round, showing that in total we have 298 gram sabhas in the sample.

Data Collection and Some Summary Findings

Data for this study are drawn from tape recordings of 298 gram sabhas in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. We hired field investigators conversant in the local languages and in English. They were tasked with tape recording the gram sabhas, transcribing them, and translating them into English. One or two field investigators visited each of the gram sabhas in our sample to record the meetings after obtaining permission from the gram panchayat president. They were also asked to dress in a simple manner and to locate themselves in an unobtrusive spot at these meetings in order not to be noticeable or influence the meeting in any way. In our large sample, there were only two or three meetings where the field investigators ended up influencing the proceedings. Our methodology worked well in capturing the discussions that took place in these meetings. The recordings were transcribed into the speakers’ respective local language and then translated into English by the same field investigators. Each transcript was also accompanied by detailed corresponding information on attendance at the particular gram sabha – the numbers of men and women attending, a rough estimate of attendance by caste, the gender and caste identity of speakers, and their official designation or social position (e.g. school principal, self-help group leader or member, club leaders, villager, etc.). Similar information was also noted for speakers who represented the state, such as political leaders, panchayat functionaries, and government bureaucrats. We also collected data on how long the meetings went on, whether they were announced beforehand, and the physical conditions under which they were held.

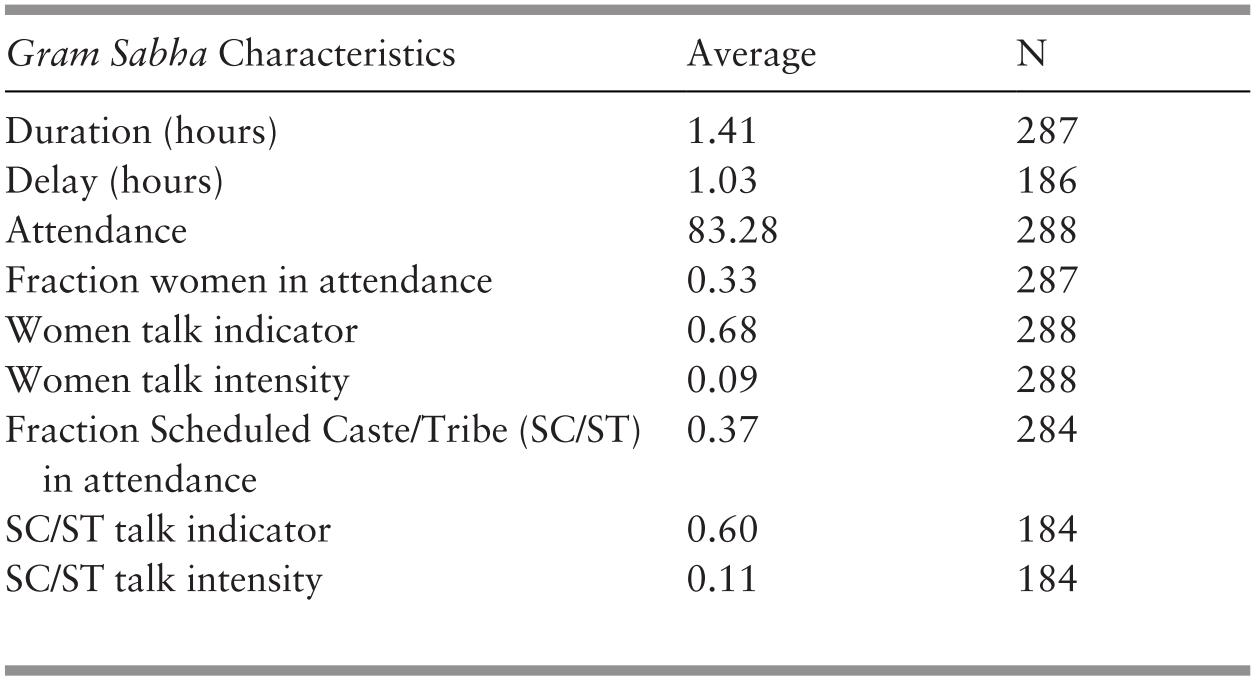

Table 1.2 provides summary information from the transcript data. The average gram sabha lasted about 84 minutes and was convened about an hour after the scheduled time (which is not atypical for public functions in India). Each transcript is therefore several pages long. About 83 people attended on average, a tiny fraction of the village population, which ranges from 2,000 to 10,000 depending on the state. Besley, Pande, and Rao (Reference Besley, Pande and Rao2005) report results from a regression analysis of household survey data from the same sample and show that, after controlling for household characteristics and village fixed effects, illiterate individuals, dalits, the landless, and the less wealthy are more likely to attend the gram sabha, while women are less likely to attend them. This is primarily because of the gram sabha’s role in selecting BPL beneficiaries, which is likely to include economically disadvantaged families. However, Besley, Pande, and Rao (Reference Besley, Pande and Rao2005) also show that this extreme form of selection is less acute in villages with higher literacy levels, where gram sabhas have more representative participation.

| Gram Sabha Characteristics | Average | N |

|---|---|---|

| Duration (hours) | 1.41 | 287 |

| Delay (hours) | 1.03 | 186 |

| Attendance | 83.28 | 288 |

| Fraction women in attendance | 0.33 | 287 |

| Women talk indicator | 0.68 | 288 |

| Women talk intensity | 0.09 | 288 |

| Fraction Scheduled Caste/Tribe (SC/ST) in attendance | 0.37 | 284 |

| SC/ST talk indicator | 0.60 | 184 |

| SC/ST talk intensity | 0.11 | 184 |

Table 1.2 shows that a third of the attendees, on average, are women and 37 percent are dalits. Women and dalits do not speak much at the meeting. The “indicator” variable has a value of 1 when any person in a category speaks in a gram sabha, while the “intensity” variable is the time that any person in that category speaks as a proportion of the total length of the gram sabha.Footnote 8 With this metric we see that 68 percent of gram sabhas had at least one woman speak, but women spoke on average for 9 percent of the gram sabha’s length. Sixty percent of gram sabhas had at least one dalit person speak, but they spoke, on average, for 11 percent of the time.Footnote 9

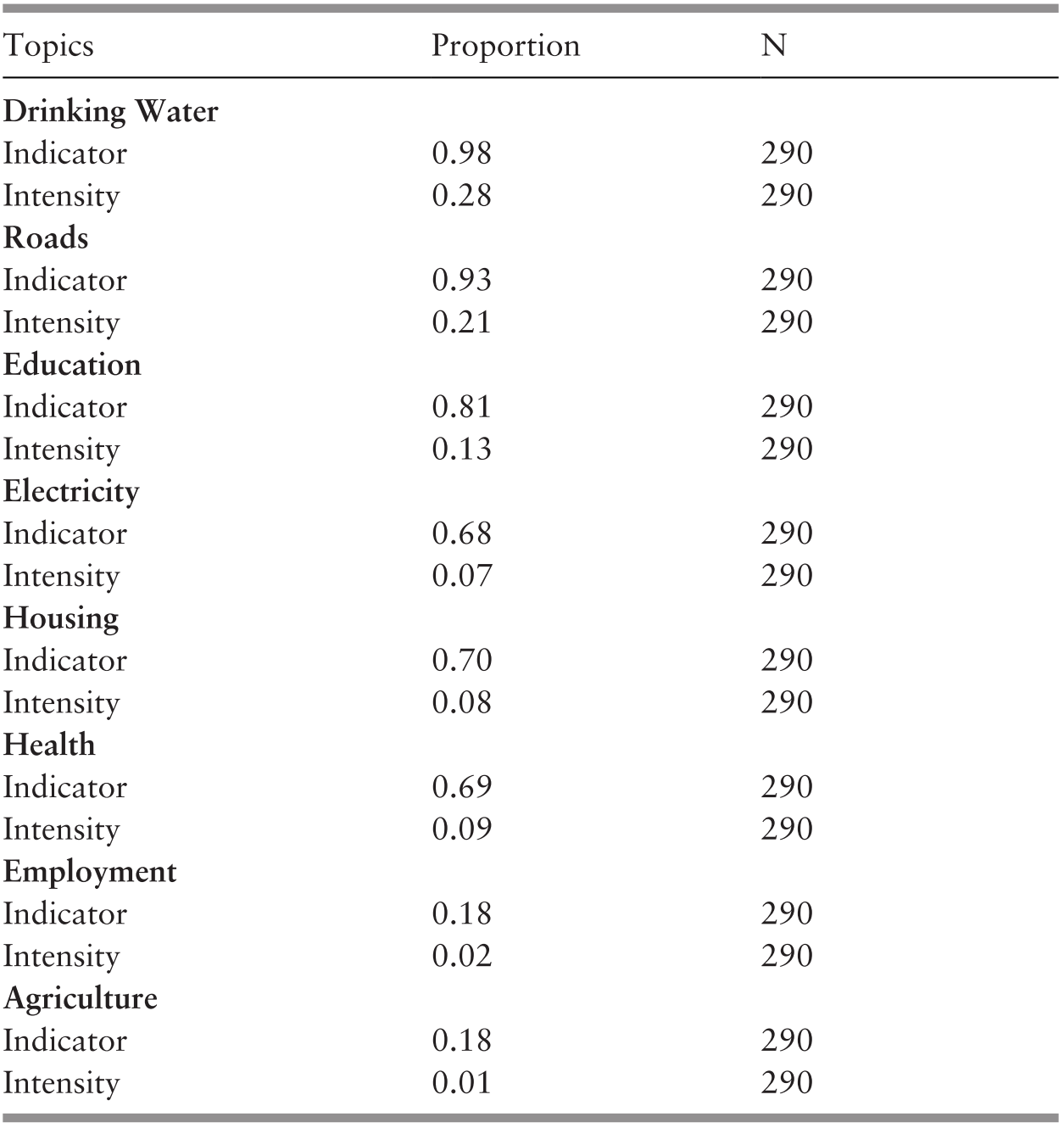

The typical gram sabha meeting begins with a presentation by the president or the secretary of the gram panchayat (henceforth GP). This is followed by a public discussion open to all participants during which, typically, villagers mention their demands and grievances, and the secretary or a member of the GP responds to them. These discussions generally center on routine problems (insufficient water supply, lack of roads, nonfunctioning streetlights, and other important infrastructure). Table 1.3 summarizes the topics discussed in the gram sabha using broad categories. We found that the discussions were dominated by issues related to drinking water and village roads, followed by education, electricity, housing, and health. Concerns about employment and agriculture featured less prominently. Discussions also addressed such complex problems as the legitimacy of having to pay taxes when obligated funds failed to arrive, and the fairness of caste-based affirmative action as a principle of resource allocation.

| Topics | Proportion | N |

|---|---|---|

| Drinking Water | ||

| Indicator | 0.98 | 290 |

| Intensity | 0.28 | 290 |

| Roads | ||

| Indicator | 0.93 | 290 |

| Intensity | 0.21 | 290 |

| Education | ||

| Indicator | 0.81 | 290 |

| Intensity | 0.13 | 290 |

| Electricity | ||

| Indicator | 0.68 | 290 |

| Intensity | 0.07 | 290 |

| Housing | ||

| Indicator | 0.70 | 290 |

| Intensity | 0.08 | 290 |

| Health | ||

| Indicator | 0.69 | 290 |

| Intensity | 0.09 | 290 |

| Employment | ||

| Indicator | 0.18 | 290 |

| Intensity | 0.02 | 290 |

| Agriculture | ||

| Indicator | 0.18 | 290 |

| Intensity | 0.01 | 290 |

Analysis of Transcripts

After identifying topics discussed and the identity of speakers, we were in a position to pursue our main goal. This was to undertake a talk-centered analysis (Eliasoph Reference Eliasoph1996; Eliasoph and Lichterman Reference Eliasoph and Lichterman2003) to understand the nature and quality of deliberation within a comparative framework – between-state comparisons of bordering villages and within-state comparisons analyzed with attention to village literacy levels. We did this by using NVivo to categorize our transcripts by district and literacy levels. We started by using NVivo for coding things like public demands versus private demands and other inductive codes. These included the types of speeches used by citizens. We categorized these as complaint, accusation, negotiation, demand, request, and pleas.

Using NVivo became increasingly difficult and problematic as we got deeper into the analysis. This was because of the nature of the data. Unlike interview scenarios where interviewee responses to questions can be conveniently coded thematically or conceptually using software-based tools, it proved difficult to code large chunks of conversation that continued on for many pages. Discussion on any given topic could continue at great length with multiple people participating and with panchayat officials responsively intervening in-between. Software-based coding techniques could not effectively or efficiently capture the differentiated qualities and content of the discourse taking place in the gram sabhas that we wanted to study.

We therefore moved to an older analytic strategy. We painstakingly identified patterns through repeated readings of the transcripts and noted down our observations regarding the content, framing, and emotional character of speeches by citizens, political leaders, and bureaucrats. Our method allowed us to explore in a fuller and deeper way the crucial, even intimate, interplay between oral democracy coming to life through gram sabhas at the grassroots of rural life in India and the role of the state.

At the initial stages of the analysis, we had frequent conversations to share and discuss our independent readings of the transcripts and observations regarding emergent patterns. Through this deliberative process and using an inductive logic, we developed a list of master themes to guide the systematic comparisons that followed. These included identifying different forms of citizenship performances by focusing on what villagers said and how they said it, how they spoke to the agents of the state, and the depth to which particular issues were discussed. We were also able to classify different types of state enactments through focusing on different facilitation regimes enacted by panchayat leaders and bureaucrats and being attentive to emphases placed in the speeches by state officials.

Our comparative analysis of gram sabha deliberations was undertaken by identifying and categorizing our observations on emerging patterns and documenting them by copying the relevant sections of the transcripts that corroborated each pattern. Eventually we developed sets of extensive notes and primary data on our pair-wise comparisons by state and literacy. At the end of this analytical exercise we developed the conceptual labeling of different kinds of talk and citizen performances and state enactments that are discussed in Chapters 2 and 3.

For the comparison by literacy, we focused on the ways in which demands were articulated and the specificity and detail of information contained in the demands made by villagers and on their efforts to seek accountability from public officials and panchayat leaders. We paid particular attention to numerical information contained in speech concerning budgets, for instance. We also paid attention to whether or not villagers voiced critiques of the panchayat and state action. We carefully tracked the intensity and style of speech in which such criticism was expressed. This book, in other words, is a product of years of immersion in the data. Although software-based quick coding helped in the initial stages of the analysis, the bulk of the analysis presented in the book was generated by traditional comparative method.

Advantages and Limitations

Our method allowed a detailed examination of a large sample of transcripts that combined the interpretative advantages of qualitative textual analysis with causal analysis derived from large-N quantitative work. Nevertheless, there were certain disadvantages to the method that we want the reader to keep in mind throughout the reading of this book.

First, unlike an ethnography such as Mansbridge’s (Reference Mansbridge1980) classic study of deliberation in Vermont or Baiocchi’s (Reference Baiocchi2005) in-depth work on participatory budgeting in Porto Allegre, we were unable to make extended visits to each one of the 173 gram panchayatsFootnote 10 in our sample. We were therefore not in a position to understand or comment upon the hyper-local context from which the gram sabhas we observed were produced. We did not have direct access, in other words, to the complex social and political dynamics underlying the discussions we recorded. Second, we do not know whether the promises made in the course of the discussions we heard were realized. We cannot say whether the promised road was constructed or whether citizens who were promised subsidized houses received them. Third, the data are, at the time of this writing, thirteen to fourteen years old and rural India has seen many changes during the intervening period.

There is related work that one of us has conducted in one of the states in our sample, Karnataka. That work reports on changes in how citizens engaged in village government over the period 2007–2011 (Rao et al. Reference Rao, Ananthpur and Malik2017). Similarly, there is work in Andhra Pradesh by Veeraraghavan (Reference Veeraraghavan2017) that describes the nature of village government systems using more recent data. There is also recent work on gram sabhas that one of us has been involved with in Tamil Nadu that uses data from 2015 (Parthasarathy, Rao, and Palaniswamy Reference Parthasarathy, Rao and Palaniswamy2017; Palaniswamy, Parthasarathy, and Rao Reference Palaniswamy, Parthasarathy and Rao2017). In the concluding chapter we place our findings based on our older transcripts within the context of this work to offer our thoughts about how much has changed and not changed since the time our data was collected. We believe that despite the changes that have taken place over the last fourteen years, most of our analysis remains relevant.

Our analysis was conducted in English. All the transcripts were translated from their respective languages – Kannada, Tamil, Telugu, and Malayalam – into English. The translations were not of uniform quality in the accuracy of their English. This is evident in some of the passages from the transcripts that we include in the text. We decided early on not to edit the English given to us by the translators except to correct obvious grammatical and spelling mistakes. We wished to preserve as much as possible the flavor of the original discussions.

Despite these limitations, our data has one key advantage. It allows us to make significant contributions to the literature on deliberation and civic life in non-Western contexts, particularly in settings marked by extreme poverty and disadvantage. Our data reflects the very large number of people living below $1 a day and who actively participate in democratic discourse despite high levels of illiteracy. The large number of sampled gram sabhas in diverse settings allows us to conduct a comparative analysis of discourse across multiple political and social contexts and levels of literacy. The density of our data is enough to study the variations between gram sabhas and the associated effects. This allows us to inductively tease out commonalities and differences in the discourse within gram sabhas as they vary across contexts.

In analyzing the data in Chapters 2, 3, and 4, we are guided by Mansbridge’s “minimalist” definition of deliberation (adapted from Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000), and we critically revisit its relevance for our data in the concluding chapter. Mansbridge defines deliberation as “mutual communication that involves weighing and reflecting on preferences, values and interests regarding matters of common concern” (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge, Heller and Rao2015, p. 27). Of the wide variations in discursive styles that we observe, more fall into this frame than any other definition of deliberation that we are aware of. They range from chaotic and disruptive forms of communication in northern Karnataka to extremely practical discussions on budgets and resource allocation in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. We argue, orally “weighing” in public such concrete things as money and construction projects works toward equalizing voice and agency. So too does orally performing the subtler attributes and aspects of democratic citizenship through the embodied assertion of dignity and the capacity and right to speak and be heard. Taking into account the acute epistemic injustices (Fricker Reference Fricker2007) that prevail in India’s rural societies, discourse within the gram sabha that creates democratic voice is as important as its effect on development outcomes. The change in direct deliberative voice in village assemblies ought to be seen as part of a process of creating a civic space where citizens can engage with elites, and with the government, in a manner that helps develop a more equal public sphere.