President Johnson understood the Vietnam policy that he had inherited from Kennedy, and the presidential tapes make clear that McNamara had informed him of the rationale behind the policy of phasing out the US presence in Vietnam. When the administration strayed from that policy, key advisors including Roger Hilsman loudly remonstrated and finally, like most of the counterinsurgency experts from the Kennedy administration, left. During his first meeting on Vietnam on November 24, 1963, the new President framed the issue in far starker and more traditionally military terms than Kennedy had been inclined to do. Moreover, Johnson publicly committed the United States to the survival of South Vietnam, something his predecessor had been more equivocal and ambivalent about. As a result, Johnson’s senior advisors began to redefine the problems in Vietnam in ways that were more amenable to an overt US role. They emphasized Hanoi’s actions and external factors instead of weakness in the South. As early as February 1964, divisions began appearing between those who favored a decisive military response and those, like McNamara, who saw military options at best as a deterrent action, a form of political communication, rather than a means to victory on the battlefield.

In the early months of the transition, Johnson virtually dictated many of McNamara’s early memoranda to him. The Secretary thereafter learned to intuit what his boss wanted to hear. McNamara’s March 1964 report, which marked a turning point in the escalatory momentum toward a military solution to the situation in Vietnam, reflected Johnson’s stated preferences. Above all, in an election year, Johnson sought – and received – policies that were “disavowable,” measures that would do “something” with little or no domestic political cost. Johnson’s bullish, if not bullying, personality and search for a consensus also influenced McNamara’s disinclination to do more than imply reservations about the administration’s policy. It spurred him to gloss over divisions among advisors to produce documents that were designed to represent an administration-wide, if tenuous, consensus.

Within the narrow purview of his role as he defined it, the Secretary of Defense gave the President and Secretary of State the tools that he thought would most economically and effectively meet their objectives. In so doing, he set up the dynamic that would persist throughout the war. He would barter with the Chiefs to incrementally approve their plans for military escalation while he waited, in vain, for the State Department to take the lead in establishing the basis for a political solution.

Moreover, Johnson influenced the underlying economic rationale that had underpinned the CPSVN. Within days of becoming President, responding to changed economic conditions and to his own philosophical bent, Johnson made it clear to his advisors that he was less concerned about the balance of payments than Kennedy had been and more committed to Keynesian economics. Johnson’s main focus was on domestic issues and his ambition to surpass Roosevelt’s achievements under the New Deal. Many of Kennedy’s advisors, who had complained that he was overly concerned with the gold outflow and insufficiently Keynesian, applauded Johnson as he launched the Great Society programs. Faced with new domestic commitments that stretched the administration’s resources, McNamara started down a slippery slope of manipulating budgetary figures to underplay the costs of the conflict in Vietnam.

As well, Johnson refashioned decision-making processes to avoid messy and open policy debates, which influenced the quality of advice he received.1 Just as Kennedy had dismantled the formal NSC structures that had informed the Eisenhower administration’s policies, Johnson reorganized the flow of advice and information to better reflect his personality. Borrowing from a system that he had used as Senate Majority Leader, he convened weekly Tuesday lunches where key decisions were made with just his three principal advisors.2 He also relied on a different and narrowing set of advisors to inform his Vietnam policy. As the war escalated, he became more inclined to receive the views of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, of external advisors who did not have the full body of intelligence available and of Secretary of State Rusk. Key counterinsurgency experts that he disliked, most notably Roger Hilsman, were pushed aside.

If on the surface and in public, McNamara became responsible for the war, behind the scenes his role was remarkably consistent across the two administrations: he did not articulate strategy per se; he implemented policy and acted as a bridge between the strategy and ambitions determined by the White House and State Department and existing capabilities and constraints. With a new President who wanted to do “something” militarily, on the one hand, and existing constraints, on the other, he presented military options that provided alternatives to traditional military deployments. The constraints that most troubled McNamara were, as always, economic and budgetary ones. More surprisingly, given that he became the face of the administration’s “credibility gap,” McNamara felt the administration should rally public support for the expanding commitment in Vietnam. In spite of his private reservations, McNamara produced the key documents that made escalation in Vietnam more likely and slid into the role of scapegoat for a policy that he, sooner than most, considered flawed.

The traditional view of McNamara’s role in the Johnson administration, and specifically his contribution to the administration’s decisions to escalate in the period between 1964 and 1965, relies on a particular interpretation of his position in the Kennedy administration and on a tendency to minimize the importance of the CPSVN plans. The withdrawal plans are usually described as secret, tentative or the product of Kennedy’s vision alone; a mere blip in the otherwise inevitable upward trajectory of US involvement in Vietnam.3 However, this view conveniently ignores the complicating fact that McNamara led Kennedy’s withdrawal plans and that they were publicized, budgeted for and set within an intellectual framework, a strategy of sorts, even if that strategy was doomed to fail as the situation in Vietnam came undone.

McNamara himself appeared to confirm the orthodox interpretation of his role in escalating the war in Vietnam in his memoirs, In Retrospect. However, in earlier drafts, McNamara explained that publicly announcing a timetable for disengagement from Vietnam in October 1963 had been controversial and added that, “I recognized the possibility that the decision could be overturned. I urged that the decision be publicly announced, thereby setting it in concrete.”4 This goes against the grain of those who say that Johnson “consciously continued his predecessor’s Vietnam policy … to demonstrate his resolve by standing firm in Vietnam”5 or that “Johnson never heard of the secret plans for getting out.”6 In his first drafts, McNamara emphasized that Kennedy believed that a successful intervention in Vietnam relied on having a strong South Vietnamese political base and, in the absence of a reliable partner, moved toward a policy of withdrawal. McNamara identified several occasions during the Johnson administration – particularly, November 1964 and most of 1965 – when withdrawal could have been considered on the same premise.

The end point for US involvement as laid out in final draft of the CPSVN, in NSAM 263 and in the press statement that emerged from the October 1963 NSC meetings would come when “the insurgency has been suppressed or until the national security forces of the Government of South Viet-Nam are capable of suppressing it.”7 Johnson knew that the objective was or, not and. He also knew that McNamara had led efforts to make the second objective the preeminent one, that is, that he supported a movement toward self-help and felt that this was ultimately a war that only the South Vietnamese themselves could win.

One presidential recording of a conversation between Johnson and McNamara on February 25, 1964, shows that McNamara had communicated the standing policy on Vietnam to Johnson in detail. In the exchange, which is worth quoting at length, Johnson, like a good student, reiterated “what [McNamara] said to [him]” and revealed his particular lens and points of view. On the policy of self-help, Johnson explained:

And it’s their war, it’s their men, and we’re willing to train them, and we have found that, over a period of time that we kept the Communists from spreading like we did in Greece and Turkey with the Truman Doctrine … We’ve done it there by advising; we haven’t done it by going off dropping bombs, we haven’t done it by going out and sending men to fight and we have no such commitment there. But we do have a commitment to help the Vietnamese defend themselves. And we’re there for training and that’s what we’ve done.

Later in the conversation, he added, “All right then the next question comes is how in the hell does McNamara think, when he’s losing a war, that he can pull men out of there. Well McNamara’s not fighting a war, he’s training men to fight a war and when he gets them through High School, they will have graduated from High School … And if he trains them to fight and they won’t fight, he can’t do anything about it.” Johnson understood that Kennedy and McNamara’s policy was one of training and training alone.8

In public and before Congress, McNamara continued to defend the validity of his policy, arguing that it was still on track. He explained, “I don’t believe we should leave our men there to substitute for Vietnamese men who are qualified to carry out the task, and this is really the heart of the proposal. I think it was a sound proposal then and I think so now.”9 At about the same time, other key advisors, including Sorensen and Hilsman, reminded Johnson about both the limited character of the US commitment to South Vietnam and, for Hilsman’s part, the counterinsurgency aspects of the strategy there. In January 1964, for instance, Sorensen suggested that “you can continue to emphasize that the South Vietnamese have the primary responsibility for winning the war – so that if during the next four months the new government fails to take the necessary political, economic, social and military actions, it will be their choice and not our betrayal or weakness that loses the area.”10 Hilsman complained that the administration was straying from the strategic concept for South Vietnam because he believed that “if we can ever manage to have it implemented fully and with vigor, the result will be a victory.”11

Even if Johnson recognized that he was changing Kennedy’s policy, he was also responding to changed circumstances on the ground. The United States’ government’s complicity in the assassinations of Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu had created additional responsibilities. The period that followed Diem’s assassination produced a heightened sense that South Vietnam was on the verge of collapse and that projects, notably the strategic hamlets program, were falling short of their aims. For its part, Hanoi stepped up its activities in the South and dispatched combat troops in a bid to achieve a quick victory before the United States could enter the war in earnest.12

Crucially, as McNamara had feared in the summer and fall of 1963, the coup leaders had not “made this thing work” and instead almost immediately descended into acrimonious divisions.13 The gamble had not paid off and all of the problems that had undermined existing programs in South Vietnam throughout 1962 and 1963 – the country’s shaky economic viability, leadership, military focus and coherence as well as its “will to win” – worsened. Despite McNamara’s early reservations about the coup, which he shared with others, notably William Colby at the CIA, they expressed little bitterness. Instead, describing a professional ethic he shared with McNamara, Colby later wrote, “The basic discipline of the career officer, civilian or military, moved me to accept as mistaken even what appeared to be wrong; my attention was directed to the problems ahead that needed to be solved rather than to recriminations about the past.”14

The situation in Vietnam would have unsettled any administration’s plans to disengage. In December 1963, following his first trip back to Vietnam after the assassinations of Presidents Diem and Kennedy, McNamara found the situation “very disturbing” and warned that “current trends, unless reversed in the next 2–3 months, will lead to neutralization at best and more likely a Communist-controlled state.”15 In a tense meeting in Saigon, he berated the coup leaders for their inability to govern and implement realistic programs. In his private notes from the trip, he worried that the “greatest weakness is an indecisive, drifting government,” while “a second major weakness is a country team which lacks leadership, is poorly informed and is not working to a common plan.”16

At about the same time, DCI McCone, who traveled to Vietnam with McNamara, wrote, “It is abundantly clear that statistics received over the past year or more from the GVN officers and reported by the US mission on which we gauged the trend of the war were grossly in error.” About the Delta region that had disturbed McNamara only two months earlier, McCone wrote, “Conditions in the delta and in the areas immediately north of Saigon are more serious now than expected and were probably never as good as reported.”17

While they may have been heightened in the aftermath of Diem’s assassination, concerns about Vietnamese leadership, the lack of cooperation in the US country team, the overextension of the strategic hamlet program or even poor intelligence were not new. During the October 1963 NSC meetings, President Kennedy’s “only reservation” with announcing the planned phaseout in Vietnam was that “if the war doesn’t continue to go well, it will look like we were overly optimistic.”18 McNamara responded to Kennedy’s reservation by saying that although he was “not entirely sure” that the insurgency could be brought under control by 1965, the withdrawal could nevertheless go ahead by that date since it depended only on the South Vietnamese completing a predetermined training program.19

Two aspects of the NSC October 1963 meetings could have kept the CPSVN on track regardless of the situation on the ground. First, that the objective continued to be to help the South Vietnamese fight the insurgency themselves and, as a corollary to this, that the US government resisted taking on a greater role in fighting the insurgency despite repeated recommendations in Washington and from the field missions to do so. One field report in October 1963 had warned, “The current war in Vietnam is too important a business to leave to the Vietnamese politicians particularly in view of the fact that it is being waged at the expense of the US taxpayer.”20 In spite of an expanded assistance mission, the administration had defined the conflict in South Vietnam in terms that would limit the United States’ commitment. As Kennedy had indicated, “In the final analysis it is the people and the government [of South Vietnam] who have to win or lose this struggle.”21

Second, the NSC October 1963 meetings and the subsequent press statement had been designed to create bureaucratic momentum behind a policy of disengagement with the hope that it would prove irreversible. At the time, while McNamara accepted that “there may be shades of difference,” President Kennedy reasoned, “I think it ties it all down,” or, as McGeorge Bundy explained: “by God we hang everybody in every department on to it.” McNamara was adamant about and succeeded in having a press statement out in order to “peg” everyone behind a policy of disengagement.22

As McNamara scribbled in his first notes for In Retrospect: “[Kennedy] was willing to supply limited support – in the form of logistics and US military trainers and advisors to help the Vietnamese help themselves with the clear objective of withdrawing that support after it had been long enough to help the Vietnamese develop a capability to help themselves if they were capable of doing so. By July–October 1963, he and I agreed that time had come.”23 As the preceding chapter explained, the October 1963 announcement of a phased withdrawal was not premised on an optimistic reading of the situation in Vietnam. Rather, it hinged on other variables including the Kennedy administration’s interest in counterinsurgency. McNamara’s suggestion in the final draft of In Retrospect that it was only in December 1963 that he realized that “earlier reports of military progress had been inflated” was, at best, disingenuous.

It was not until January 1964, when it became clear that Johnson was uninterested in the CPSVN, that McNamara began advancing the argument that his plans had always been conditional on the situation in South Vietnam. His statements to various audiences at that time, including the House Armed Services Committee: (HASC), provide putative evidence that as far as McNamara was concerned the CPSVN had always been contingent on progress in the field, progress that he had believed was forthcoming in the fall of 1963.24 However, until that point, McNamara was largely, and at times deliberately, myopic to negative reports coming from the field. Instead, managerial priorities and realities in Washington conditioned the timetable and content of the CPSVN. By rewriting the history of the CPSVN, McNamara was also disguising the change in policy that was happening during the transition.

The decision to expand US involvement in South Vietnam as the situation there deteriorated was also, to some extent, a product of bureaucratic machinery rather than an individual’s decision. Yet, as one scholar has written, “The dominant variable of any advisory system is the personality of the President.”25 Given McNamara’s strict conceptions of loyalty, the President was in fact “the” determining variable in understanding his shift. And while it may be unfair to characterize Johnson’s approach to Vietnam as less sophisticated than Kennedy’s, this was precisely McNamara’s assessment. He explained that Johnson had removed key qualifiers to the US commitment to South Vietnam, notably a strong political base and the ability of the South Vietnamese to win the war themselves. He added, “In that sense, I think his view was what I termed more simplist [sic]. I don’t like the term but, for the minute, it conveys my thought.”26

President Johnson’s rather more “simplist” understanding of Vietnam shaped the terms of the debate and the scope of the recommendations that McNamara presented to him. In one telling exchange with McNamara on March 2, 1964, Johnson instructed McNamara: “I want you to dictate to me a memorandum of a couple of pages, uh four letter words and short sentences and several paragraphs so I can read it and study it and commit to memory … the Vietnam picture if you had to put in 600 words or maybe a thousand words if you have to go that long. But just like you’d talk.”27 These types of exchanges add credence to the view that Johnson lacked the nuance of his predecessor on foreign policy issues, “which left him vulnerable to clichés and stereotypes about world affairs.”28

The presidential recordings of conversations between President Johnson and McNamara also often reveal a hierarchical relationship confirming Yarmolinsky’s view that if McNamara’s relationship with Kennedy had been one of “real mutual trust and affection,” Johnson “was his boss, and he was Johnson’s most useful servant.”29 Whereas McNamara often interrupted Kennedy and at times dominated their conversations, Johnson lectured and dictated, instructing McNamara that “I’ll tell you what I’d say about it.” In exchanges that sometimes appeared excessive, Johnson complimented McNamara, calling him “McCan-do-man” or his “executive VP,” somebody he valued because “I need to issue instructions and see that they’re carried out.”30 McNamara’s old colleagues and friends, particularly Robert Kennedy, became “outraged by McNamara’s servility” and the “humiliations” he endured “out of deference to Johnson or his office.”31 Ultimately, McNamara’s relationship to Johnson reflected his ambivalent depiction of Johnson as someone who was “by turns open and devious, loving and mean, compassionate and tough, gentle and cruel … a towering, powerful, paradoxical figure.”32 Their relationship also explains McNamara’s role during the transition.

Despite his flattering remarks, Johnson allowed and even encouraged McNamara to become the public face of escalation in Vietnam. In the key period of the spring of 1964, Senator Morse first designated the war in Vietnam as “McNamara’s war,” a moniker President Johnson reveled in. The presidential recordings are replete with references to Johnson’s amusement with the notion: he laughed that it was unfair that it was “only McNamara’s war”33 or described the situation as “your war in Vietnam.”34 For his part, McNamara slavishly took responsibility for the complicated situation because it would “take a lot of heat off of you Mr. President.”35 When, in September 1964, press reports first started pointing the finger at Johnson for the administration’s policy in Vietnam, he teased McNamara that it “looks to me that [Texas Governor] John Connally, the two of you got together and transferred it from McNamara’s war to Johnson’s war,” that he had “never heard a word about Johnson’s war until the two of you got together,” and mused that “I kind of enjoyed [Senator Barry] Goldwater’s talk about McNamara’s war.”36 Ultimately, just as Kennedy had made McNamara the public face of the withdrawal plans and charged him with the organization of a policy for Vietnam, Johnson ensured that McNamara was also identified with the decision to escalate.

However, the impetus for escalation had come from Johnson, not McNamara. Johnson had defined the parameters of the discussion on Vietnam with his almost immediate commitment to “win” in Vietnam.37 McNamara wrote that “President Johnson made clear to Lodge on November 24 [1963] that he wanted to win the war, and that, at least in the short run, he wanted priority given to military operations over ‘so-called’ social reforms. He felt the United States had spent too much time and energy trying to shape other countries in its own image. Win the war! That was his message.”38 Although in an interview with CBS in the wake of that meeting, Ambassador Lodge stated that “policy [was] unchanged and that “it was not a decision-making type meeting,” Johnson’s “message” influenced the shape of policy in the ensuing months.39

Within weeks, Johnson wrote to General Taylor that “The more I look at it, the more it is clear to me that South Vietnam is our most critical military area right now” (emphasis added).40 In turn, this fed into the kind of advice he demanded from McNamara. During McNamara’s first trip back to Vietnam in December 1963, his team’s terms of reference as he communicated them to Ambassador Lodge were to plan for “varying levels of pressure all designed to make clear to the North Vietnamese that the US will not accept a communist victory in South Vietnam and that we will escalate the conflict to whatever level is required to ensure defeat.”41 With Mansfield and others floating the idea that negotiated neutralism might be an avenue the administration should explore for South Vietnam, Rusk felt it necessary to reassure the South Vietnamese with an “authoritative statement of American war aims and policy on neutralization.”42 That policy was established before McNamara had left Washington. As Forrestal wrote to Lodge, the primary reason that “McNamara is coming out” was to send a signal “that we are against neutralism and want to win the war.”43

In the same February 25, 1964, tape where Johnson spelled out the Kennedy/McNamara policy, he also revealed his distinctive perspective and biases. For instance, he told McNamara, “We have a commitment to Vietnamese freedom. Now, we could pull out of there, the dominos would fall, that part of the world would go Communist.” This was a stronger commitment than McNamara had allowed in his October 1963 report.44 It was also the only exchange where Johnson directly addressed the withdrawal plans. The remarks challenge the idea that he chose to continue Kennedy’s policy in Vietnam. He said: “I always thought it was foolish to make any statements about withdrawing. I thought it was bad psychologically. But you and the President thought otherwise and I just sat silent.”45

During his “silent” years as Vice President, and on the rare occasions when he had been consulted, Johnson had encouraged “tougher” responses. During his trip to South Vietnam in May 1961, he promised that the United States would stand “shoulder to shoulder” with South Vietnam and, in a seemingly unprompted way, asked Diem if he needed US or SEATO intervention.46 In his trip report, he reiterated the domino theory and argued that “The failure to act vigorously to stop the killing now in Viet Nam may well be paid for later with the lives of Americans all over Asia.”47 Even while he recognized the dangers of finding the United States embroiled in a “jungle war,” he argued for a substantial increase in economic aid and a more active military role. He ended his report to the President ominously: “There is a chance for success in Viet Nam but there is not a moment to lose. We need to move along the above lines and we need to begin now, today, to move.”48 Kennedy and McNamara largely ignored the Vice President’s warnings and recommendations.

Now that Johnson was President, however, McNamara could not ignore him, and on paper, McNamara became a leading force behind the decisions to favor military tools in Vietnam. At the same time that McNamara was insisting on the limited character of the US commitment to Vietnam, his memoranda encouraged aggressive policies that represented a clear break with the policies he had supported until then. As early as December 1963, armed with his negative appraisal of the situation in Vietnam, McNamara recommended that the administration should be “preparing for more forceful moves.”49 By March 1964, in his first joint trip back to South Vietnam with Maxwell Taylor, his already pessimistic appraisal of the situation darkened further and he came out even more strongly in favor of the very same military response that he had resisted during the Kennedy administration.

McNamara’s March trip report was riddled with contradictions and reflected long-standing bureaucratic conflicts. McNamara wrote that the policy of phased withdrawal and of considering the conflict as one for which “the South Vietnamese must win and take ultimate responsibility” was “still sound.” At the same time, he inferred that this was no longer a substitute for victory in the traditional sense. Now he wrote, “The US at all levels must continue to make emphatically clear that we are prepared to furnish assistance and support for as long as it takes to bring the insurgency under control.”50 The report’s suggested policy directions were equally contradictory. On the one hand, it stated the “so-called ‘oil spot’ theory is excellent” and reiterated the key role for counterinsurgency programs. On the other, it recommended preparing for graduated “air pressure” over North Vietnam.51 Until this point, the counterinsurgency strategy had been designed as a substitute to conventional force and precluded a bombing program. Even if the report made due reference to neutralization and withdrawal, it also quickly rejected them as viable policy options.

Ambassador Ormsby-Gore’s notes from a dinner with McNamara the night before he departed on this March trip suggest that even if McNamara was publicly expanding the commitment to South Vietnam and proposing policy options that would extend “American military commitments,” in private, he still held on to a policy he later ascribed to Kennedy, namely that there would be no point in expanding the US commitment to South Vietnam without a viable political base in the country. The Ambassador found McNamara “more despondent about the situation there than I have ever seen him” and very concerned about South Vietnam’s new leadership’s ability to “restore morale and achieve growing popular support.” Later, he wrote: “He was not in a belligerent mood and although he has spoken to me previously about examining the possibilities of hurting the North Vietnamese, I gained the strong impression that unless he came back feeling that there was a reasonable chance of pulling the situation round in South Vietnam, there would be no value in risking a further extension of American military commitments in the area such as would result from trying to carry the conflict over the border into the North.”52

Instead, McNamara’s trip and report were stage-managed with a view to placating emerging divisions in the administration and on the home front in an election year. Just days before the trip, Johnson basically dictated what would eventually became the report’s policy suggestions: “I’d like you to say that there are several courses that could be followed.” These were: sending in troops, neutralization that would result in “Commies … swallow[ing] up South Vietnam,” pulling out which would result in dominos falling throughout the region or continuing training.53 In other words, the crucial March 1964 report was not so much a reflection of McNamara’s views as it was what Johnson said he’d “like [McNamara] to say.”

William Bundy, who replaced Hilsman as Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, wrote most of the March report as well as McNamara’s subsequent speech in Washington before the latter had even left for Saigon. The State Department was on the ascendancy on Vietnam in these early months. William Sullivan headed a State-led working group that had supplanted the Special Group (CI) in overseeing activities in Vietnam. The State Department took a more traditional approach to the problems in Vietnam and moved away from counterinsurgency theories. In particular, from December 1963, the department sought to resuscitate the Jorden report that McNamara had previously suppressed and Rostow had championed, which argued that the problems in Vietnam were a result of external aggression from the North rather than a product of failures in the South.54

While it was true that Hanoi had accelerated infiltration and stepped up its activities in the wake of the Diem coup, this changed focus also reflected a willingness in the State Department to prepare for actions against the North. By February, both Rostow and William Bundy thought the trip team should “make an effort to produce a lucid assessment of the relative role of external intrusion” and that “the answer may lie in hoarding certain firm, relatively recent evidence.”55 Sensing the public relations opportunity, Johnson suggested McNamara himself “carry off the plane a recoilless rifle as evidence of North Vietnamese support.”56

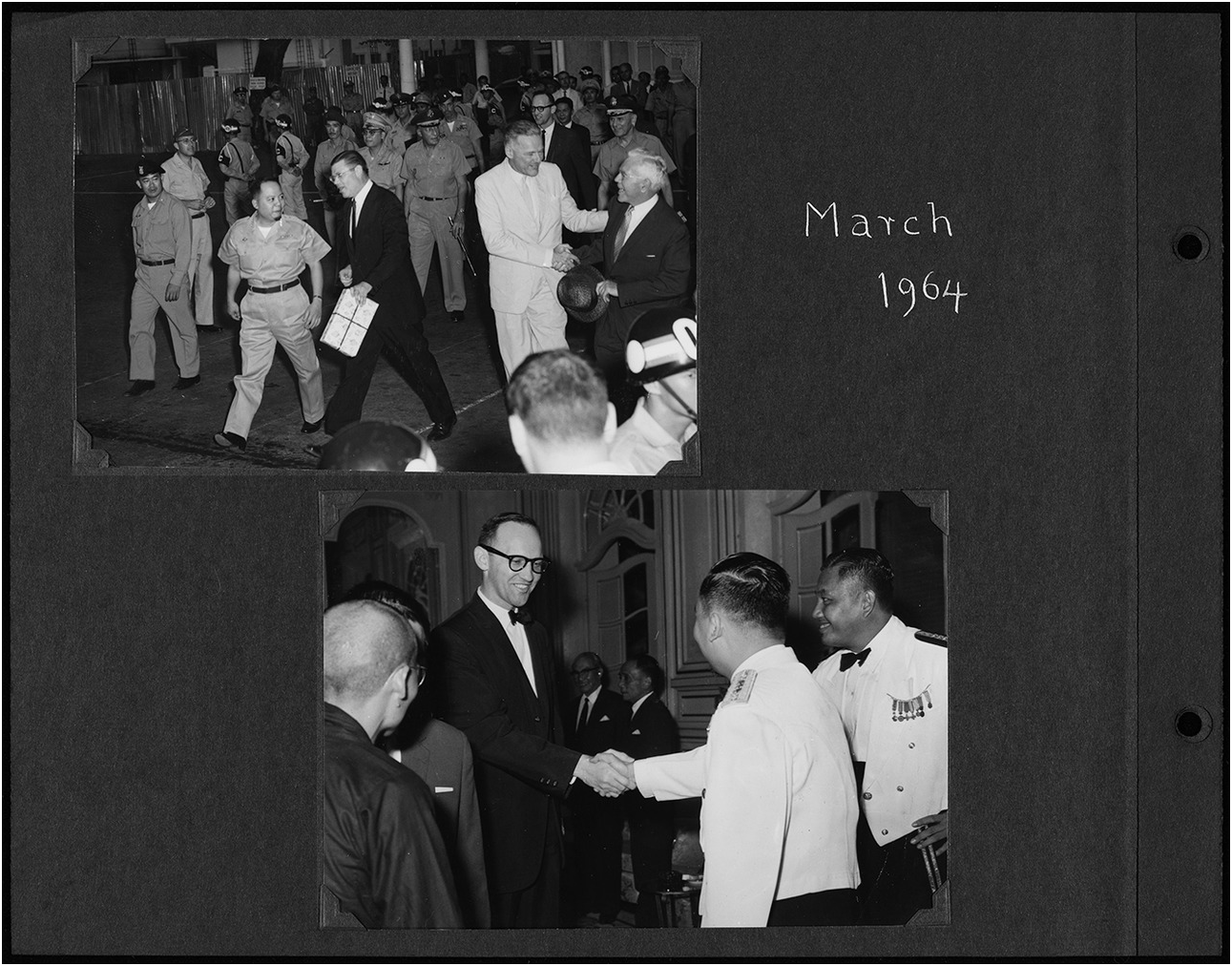

McNamara’s March trip was a public relations exercise (see Figure 7.1). The uptick of terrorist activities in South Vietnam, including the bombing of a movie theater in Saigon in February, had created pressures for the administration to do more, at least to protect its own citizens. However, given the electoral calendar, Johnson wanted to delay actions that might be too visible or contentious. In December 1963, McNamara had considered “disavowable actions.” A month later, the President approved sabotage actions against the North known as OPLAN 34A that were only nominally under South Vietnamese control. By March, McNamara lifted his resistance to the introduction of jets to Vietnam under the Air Force’s Farmgate operations: officially, they were introduced for “logistical reasons”; unofficially, they were deployed to prepare strikes on the North “contrary to policy that US was to train VNAF [Vietnamese Air Force].”57 In his notes from the March trip, McNamara looked for “plausibly deniable” actions that might “make plain US can bring military pressures to bear on North Vietnam without being overt.”58 His new Assistant Secretary for International Security Affairs, John T. McNaughton, cautioned that “there is no magic formula” before they left for Vietnam.59 Yet this was exactly what the administration sought: a policy that would shift the situation on the ground without attracting attention outside Vietnam.

Figure 7.1 A page from John T. McNaughton’s scrapbooks. Left: Secretary of Defense McNamara arrives in Saigon and walks with newly minted Prime Minister General Khanh to his right and Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge to his left. His Assistant for International Security Affairs McNaughton is in the background, flanked by General William Westmoreland to his left and General Paul Harkins to his right, March 8, 1964. Right: McNaughton at a reception at the US Embassy in Saigon, undated (March 1964). The trip was largely a public relations exercise; the trip report was written before they left.

The administration also wanted a policy that could give the impression that civilians and the military were united. McNamara’s instructions to the trip team speak to his efforts at forcing a consensus. He indicated that they would not prepare a final written report, but that, instead, he would report orally to the President. He asked them to minimize contact with the press and not to send interim reports back to their own departments.60 Where divisions existed, McNamara overruled them. In January and February, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had suggested the administration move toward victory by removing “self-imposed restrictions,” but McNamara capitalized on divisions in their midst. Where the Army agreed with McNamara that the problems in Vietnam inherently lay in the South, the Air Force suggested an aggressive push on the North. McNamara distilled the Chiefs’ contradictory views under his recommended “actions.” Before he left, he proudly told Johnson, “Divide and conquer is a pretty good rule in this situation. And to be quite frank, I’ve tried to do that in the last few weeks and it’s coming along quite well.”61

Crucially, McNamara had to reconcile the momentum toward escalation with continued insistence that withdrawal was still on the cards as the South Vietnamese were trained. Robert Thompson counseled that while the prospects for winning were “gloomy,” the situation was “not yet desperate” if the administration refocused on pacification without a too strong US presence. He now cautioned against mentioning withdrawal and suggested the administration might put a positive spin by saying it would stay “as long as it may be necessary.”62 Accordingly, McNaughton edited Bundy’s passage of the trip report to add that assistance would be provided “regardless of how long it takes” and that “previous judgments that the major part of the US job could be completed by the end of 1965 should now be soft pedaled and placed on the basis that no such date can now be set realistically until we see how the conflict works out.”63 Still, within ten days of submitting the report, planning for the withdrawal of US forces from Vietnam was formally, though not publicly, terminated.64 When the 1,000-man withdrawal did go ahead, it was done on the basis of “efficiencies” rather than as part of a larger program of phasing out.

Ultimately, the mood that Ormsby-Gore had observed on the eve of the trip was likely less a reflection of McNamara’s concerns about what he might find in South Vietnam and more about the momentum he could see was gathering in Washington around the option of using military force and against his plans for phased withdrawal.65 This is not to say that Johnson did not share McNamara’s concerns about the policies on offer. In a private conversation with Richard Russell on the eve of McNamara’s departure, Johnson worried about the options available to him and the lingering feeling that he was boxed in, not “know[ing] any way to get out.”66 Nevertheless, he encouraged McNamara to come back with recommendations that increased US involvement in South Vietnam.

Ever the political animal, Johnson was especially concerned about the domestic reaction to the growing commitment in Vietnam. The timing of the trip and McNamara’s subsequent speech in Washington coincided with increasing murmurs in the SFRC and in editorial pages about the situation in South Vietnam and President de Gaulle’s renewed push for neutralization of the entire Indochinese peninsula. In January 1964, an exchange of letters between Senator Mansfield and Johnson spurred a discussion within the administration about the limits of the United States’ commitment to Vietnam. Using the same arguments McNamara had made in the preceding months, Mansfield addressed the danger of “another China in Vietnam” and noted, “Neither do we want another Korea. It would seem that a key (but often overlooked) factor in both situations was a tendency to bite off more than we can chew. We tended to talk ourselves out on a limb with overstatements of our purpose and commitment.” He ended with a warning to the President that “there ought to less official talk of our responsibility in Vietnam and more emphasis on the responsibilities of the Vietnamese themselves.”67 In the days before the trip, in front of the SFRC, both Rusk and McNamara had to rebut liberal senators’ contention that the situation was hopeless, that it was essentially a civil war as the influential columnist Walter Lippmann had written and to justify why the administration was not pursuing the neutralization route.68 “The basic purpose of the speech,” Sullivan explained, “is to obtain broad support and particularly to state objectives which will be endorsed by the Mansfields and the Lippmanns. More pointedly, it is intended to separate the Mansfields from the Morses.”69

Thus, ten days after his return from Vietnam, in the speech that William Bundy had also written for him on the back of the trip report, McNamara publicly defended a shift toward a more open-ended commitment to counter growing criticism in the United States. His speech continued to make reference to Vietnam as a “test case” for counterinsurgency even while it now put more onus on the external dimensions of the conflict.70 Whereas the October 1963 announcement promised a commitment until “the insurgency has been suppressed or until the national security forces of the Government of South Viet-Nam are capable of suppressing it,” he now publicly pledged a US commitment for “as long as it takes,” as Robert Thompson had suggested.71 The speech, and the trip report, were pieces of a delicate balancing act aimed at convincing disparate critics that the administration was not planning a major escalation, that the fundamental policy was continuing but instead, as Johnson explained to McNamara, “going to do more of the same, except we’re going to firm it up and strengthen it.”72

The March 1964 shift represented the particular flavor of an administration with Lyndon Johnson at its helm. Just as the October 1963 policy and the CPSVN flowed from a policy framework set out by President Kennedy, McNamara’s increasingly hawkish recommendations in early months of 1964 flowed from President Johnson. In addition, Johnson’s reorganization of national security decision-making had an indirect influence on policy outcomes: it elevated Rusk on Vietnam policy. The idea that Johnson continued Kennedy’s policy has also relied on stressing the continuity of personnel. The reality is that key advisors were quickly sidelined, including Robert Kennedy, who had led the Special Group (CI), and Averell Harriman, who was made roving Ambassador for African Affairs. Other advisors, such as Sorensen, Forrestal and Hilsman, who had signaled early on to Johnson that the administration was not keeping to the Kennedy administration’s policy, were also set aside.

Rusk, instead of more junior counterinsurgency experts such as Hilsman, now had greater clout. In the October 1963 NSC meetings, when the Kennedy administration committed itself publicly to a policy of disengagement, Hilsman and Harriman, not Rusk, had represented the State Department. Rusk was in Europe at a NATO summit at the time. Not only was he absent from the key NSC meetings, he was brought up to speed on the policy only after the public announcement had been made. Since the strategy that underpinned McNamara’s withdrawal plans stemmed from advisors like Hilsman rather than Rusk, their subsequent removal from decision-making on Vietnam was also significant.

Sorensen, who had alerted Johnson to the limits of Kennedy’s commitment and who had suggested ways of disengaging from Vietnam in a way that would not endanger US credibility, was the first to go. Kennedy’s assassination had particularly affected him. In January, he indicated that he “didn’t want to come back” to the White House, which he described as a “very sad place.”73 In private, he spoke harshly about Johnson: “to me he personified the kind of hyperbole and hypocrisy that defined the worst aspects of politics in my eyes.”74 These comments suggest that his reasons for leaving hinged on his personal dislike of Johnson.75

Forrestal was also sidelined and eventually left. In the early days of the transition, Forrestal had gone along with the administration’s moves. At McGeorge Bundy’s request, he produced an economic and political program to match McNamara’s planning for graduated escalation. However, he was ambivalent about the administration’s proclivity to define the conflict in increasingly conventional military terms. By the spring of 1964, he broke with McGeorge Bundy and wrote, “What we are dealing with is social revolution by illegal means, infected by the cancer of Communism.” He also went back on his suggestion that physical security achieved through military means was a prerequisite for the other social and economic programs. He now said: “I believed this, too, until after the third or fourth trip to Vietnam. But the problems are not separable. The Viet Cong know this. It is why they are winning. To the extent we manage our economic assistance, our military action, and our political advice so as to perpetuate a social and economic structure which gave rise to the very problem we are fighting, we will fail to solve the problem.” Ultimately, by January 1965, he too left the administration, disillusioned and depressed.76

As for Hilsman, under the new administration he reaped the consequences of his antagonistic relationship with both the military and his boss, Rusk, whom he had continuously circumvented in the past. Although as a fellow Texan, Hilsman felt that he and President Johnson “should have gotten along,” he became isolated in the new administration.77 Rusk later said, “I fired him because he talked too much at Georgetown cocktail parties.”78 Taylor explained that Hilsman was dismissed because he had antagonized military advisors by second-guessing their recommendations – “it just shows what happens when you put a West Pointer in the State Department” – and because he “drove McNamara mad.”79 In an effort to avoid a noisy departure, he was offered the Ambassadorship in the Philippines where he had spent a part of his childhood. He chose instead to resign.80 Despite the administration’s attempts to contain the news of his resignation, it made the front page of the New York Times of February 25, 1964, where he insisted, “I am not quarreling with policy” and praised Johnson for his “vigor and sureness.”81

Not one to keep his opinions to himself, however, Hilsman protested loudly within corridors of power that the administration was not continuing Kennedy’s policy and he continued to voice this opinion after he left government. In a document entitled “Last Will and Testament: South Viet-Nam and Southeast Asia,” which he sent to Rusk on March 10, 1964, Hilsman reacted to the administration’s gradual move away from the counterinsurgency strategy he had helped to design. He reminded his former boss that the strategy rested on the “Strategic Concept for South Vietnam,” though he did not mention that the “Strategic Concept” was his work. He described the strategy as still “basically sound” even while he acknowledged its failings on the field. He also responded to the administration’s choice to consider more traditional, military tools and wrote: “In sum, I think we can win in Viet-Nam with a number of provisos. The first is that we do not over-militarize the war – that we concentrate not on killing the Vietcong and the conventional means of warfare, but on an effective program for extending the areas of security gradually, systematically and thoroughly. This will require better team work in Saigon than we have had in the past and considerably more emphasis on clear and hold operations and on policy work than we ourselves have given to the Vietnamese.”82

By May 1964, after a final meeting with McNamara, Robert Thompson too was forced to acknowledge that the new administration was no longer listening to him and that “his usefulness had come to an end.” The British advisory mission closed at the end of 1964 by which time Thompson had concluded that the war was no longer winnable and the administration should move to negotiations.83 In a scathing analysis of the Johnson administration, he explained how, in the early months of 1964, in part because the new President relied “too much” on military advisors and “tradition” rather than advisors like him, the “original position, in which the United States was merely helping the South Vietnamese to win its own war, was gradually changed, to one in which it had to interfere in South Vietnam.”84

Ultimately, all the key individuals who questioned the administration’s decisions on Vietnam or provided the intellectual rationale for a counterinsurgency strategy were pushed out. McNamara, who could have kept their voices alive within national security decision-making, chose to be loyal to the President. Many months later, in March 1965, after the start of Operation Rolling Thunder, McNamara reassured Johnson that the administration was in general agreement and that leaks to the press were less likely now. He noted, “There’s been more unity both beneath and above surface on Vietnam in the last few months than at any time in the last several years. And more unity in the upper levels than you did, let’s say in the Hilsman/CIA/Defense Department wrangle.”85

Personnel changes in Washington shifted the focus away from counterinsurgency in Vietnam, as did practical realities about the South Vietnamese and US mission’s inability to execute and implement existing plans. Coups in Vietnam succeeded themselves and each fresh government promised a new pacification plan. But political instability and corruption undermined each attempt. The US mission, which splintered along bureaucratic lines, was also incapable of coordinating different civilian and military programs. In the military field, where many irregular forces had already been subsumed under military command, the “conventionalization” of forces began in earnest. One Special Forces history explained how “very few hamlet militia were trained after November 1963, almost none after April 1964.”86

The administration’s move toward a more open-ended commitment to Vietnam in 1964 had important repercussions on the economic issues that had underpinned the CPSVN. The counterinsurgency strategy had dovetailed with McNamara’s efforts to tackle the balance of payments deficit, while the CPSVN addressed the SFRC’s attack on the MAP as well as the Kennedy administration’s general tendency toward fiscal restraint. By contrast, Johnson embraced Keynesian economics and was willing to run large deficits. Even so, while the administration moved to a more “forceful” program in Vietnam that no longer fell within the limited purview of a traditional military assistance program, Johnson encouraged McNamara to cut costs and especially to undervalue costs for Vietnam lest they scuttle his domestic ambitions by provoking a congressional debate over his ambition to have both “guns and butter.”87 Given his bridging role at the OSD, McNamara early on recognized the tensions inherent in the White House’s competing ambitions.

Even as he integrated the notion that South Vietnam’s problems were externally driven in his reports and pubic pronouncements, McNamara was reluctant to call the situation in Vietnam a “war.” By keeping the Defense Department’s peacetime accounting, it was relatively easier for him to underestimate the true costs of the war. In the first months of the administration, Johnson instructed McNamara to underestimate his annual budget requests for the Department and for Vietnam specifically. McNamara submitted the budget to Congress in the fall knowing full well that he would submit a supplementary request in the spring. He suggested this delaying technique to President Johnson but as early as December 1963 expressed concern that it might “screw up the integrity of the budgeting process here.”88

McNamara’s willingness to loosen his control of the budget is explicable when set against the backdrop of the administration’s broader economic policies. Unlike Kennedy, who erred on the side of fiscal conservatism and, in so doing, angered his liberal economic advisors, Johnson was applauded for his willingness to embrace Keynesianism. He proceeded with Kennedy’s planned tax cut even as he significantly increased federal spending on social programs as part of his Great Society. To Walter Heller, he explained that he was a “Roosevelt New Dealer” and “to tell you the truth, John F. Kennedy was a little too conservative to suit my taste.”89 While Kennedy had ruled out the possibility of expanding spending on the back of the balance of payments deficit and faced greater resistance from the business community as well as Congress, these constraints bothered Johnson much less.90

Paradoxically, President Johnson seemed to reassure the business community and, as some of the offset programs with European allies and a “buy American” program within the Defense Department began to take effect, the balance of payments crisis seemed to have subsided by 1964. Also, as Secretary Dillon, who stayed on for the first year of the Johnson administration, recalled, “Now Mr. Johnson had plenty of other things to do and he didn’t have this sort of interest. He knew it was important. He supported our effort in helping international monetary cooperation – and later on I think he developed a real interest in it when he had more time. But that came, I guess, after I’d left.”91

Dillon, who had benefited from an unusually close relationship with President Kennedy and encouraged him to err on the side of fiscal prudence, saw his influence wane in the transition and recalled a President who “wasn’t interested in what was going on” on the economic front.92 In December 1963, he tried in vain to attract the new President’s attention to defense outlays overseas and was irritated when Johnson went further than his predecessor in promising to keep six divisions in Europe “so long as they are needed,” adding “and under present circumstances there is no doubt that they will continue to be needed.” He warned the President that the Republicans could use the need to reduce overseas deployments, not least for balance of payments reasons, as a campaign issue and that it was time for substantial troop reductions especially in Europe.93

Johnson promised Senator Harry Byrd, the Senate Finance Committee’s Chairman, a reduction in federal expenditures to below the $100 billion mark in exchange for the passage of the Kennedy tax cut.94 Although this reduction had largely been agreed on between Dillon and President Kennedy, it allowed Johnson to “appear even more conservative in cutting expenditures than maybe he really was.”95 In order to keep expenditures down while moving ahead with the costly Great Society programs, Johnson had to cut back elsewhere, notably on the defense budget. Although the PPBS program was explicitly designed not to have budgetary ceilings de facto, McNamara reintroduced them to fit Johnson’s guidelines. As he explained to Johnson in a private discussion about the FY64 budget, the JCS wouldn’t “know that I set the dollar limit first.”96

Kennedy’s liberal critics praised the “spectacular savings” made to the defense budget and what they saw as the reallocation of funds to welfare spending. They also applauded Johnson’s “great skill in dealing with Congress”97 even while some mournfully noted that, on the domestic front, “President Kennedy apparently had to die to create a sympathetic atmosphere to his program.”98 At the Defense Department, the published numbers were impressive. McNamara cut the defense budget by almost $2.5 billion in FY64 and a further $1.2 billion in both FY65 and FY66. He achieved these cuts by moving ahead with his base closure and cost reduction programs, both initiated under the Kennedy administration, but more problematically by delaying procurement decisions.99 For a time, McNamara’s efforts kept Vietnam off the radar and avoided a congressional debate on the administration’s broader economic policies.

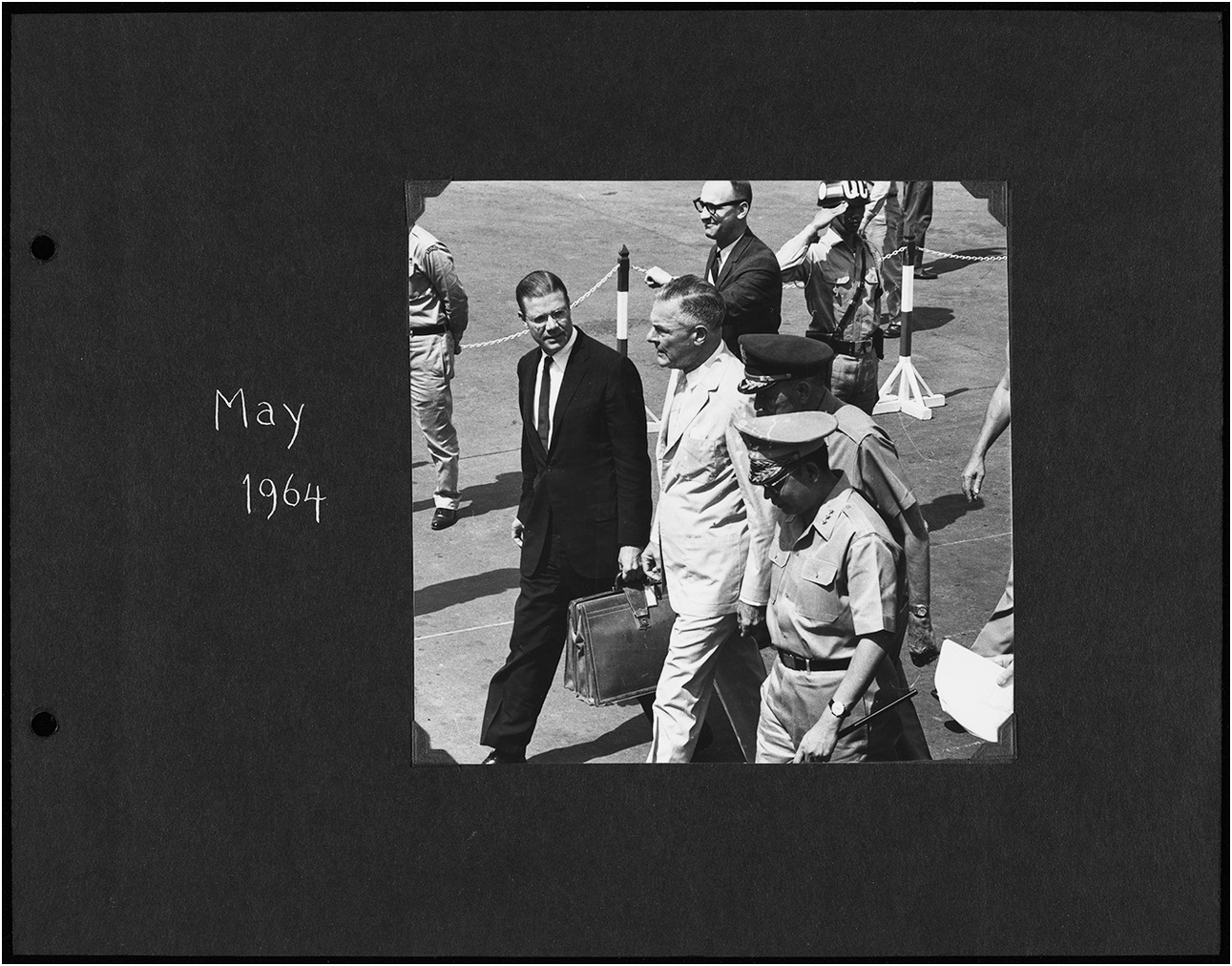

As Kennedy’s counterinsurgency and fiscally conservative advisors’ influence waned in the Johnson administration, the rationale for the CPSVN fell apart. Instead, by May 1964, when McNamara returned again to Vietnam, he had to contend with obvious failures in the field and particularly with the growing pressure to do “something” to stop the situation in South Vietnam from unraveling (see Figure 7.2). McNamara blamed Lodge for many of the program’s failures. In his memoirs, he described Lodge as “aristocratic and patrician to the point of arrogance.”100 In private, he thought Lodge lazy, as the Ambassador was known to disdain administrative tasks and run “a pretty relaxed daily regime.”101 He scarcely respected the rest of the country team. He described Joseph Brent, the head of the USOM, as “washed up”; Ogden Williams, who headed the rural affairs program, as “not filled with a sense of urgency”; and concluded that there was “no effective direction of the counterinsurgency program in the country team.”102

Figure 7.2 A page from John T. McNaughton’s scrapbooks. Secretary of Defense McNamara arrives again in Saigon. He walks with Ambassador Lodge, General Harkins (who was about to retire), General Khanh and McNaughton behind him, May 12, 1964.

In lieu of the existing policy, a bureaucratic consensus around bombing North Vietnam emerged. Ambassador Lodge joined the chorus of advisors who argued that a bombing program could bolster existing programs in the South, that it could create breathing room for the South while forcing the North to negotiate or reduce infiltration. McNamara’s May trip was thus designed to study when and whether to start bombing and how it could complement activities in the South. Where previous South Vietnamese leaders had resisted such a bombing program, the new Prime Minister Nguyen Khanh, with some nudging from Lodge, now described it as “desirable.” McNamara agreed to study the bombing program even if the presidential recordings, even more than the written record, reveal that he questioned its effectiveness and bemoaned Wheeler’s emphasis on “planes.” He explained to Johnson: “And the planes, Max Taylor agrees, are not the answer to the problem. Whether we should have more planes is another question but it’s not going to make any difference in the short-term, that’s for certain.”103

Still, with an election nearing, Johnson needed political protection against Lodge and the Chiefs. McNamara returned from his May trip to a letter from Representative Carl Vinson, the Chairman of the HASC, who drew attention to an article in US News & World by one of his constituents, an Air Force widow who, in contrast to liberal critics, decried the “incompetence, cowardice… among many of the public officials directing war operations.”104 With his strong foreign policy credentials and centrist views on social issues, Lodge was a potential political threat to Johnson, who might add to the chorus about civilian timidity in Vietnam. In March, while McNamara was in Vietnam, Lodge had won the Republican primary election in New Hampshire although he was not officially campaigning as he was precluded from doing so as a civil servant.105 Fearing public criticism on Vietnam policy, Johnson asked McNamara to “build up a record” of support for Lodge. In a press conference, the President had underhandedly commented that “he makes recommendations from time to time. We act promptly on those recommendations.”106 For his part, McNamara quoted Lodge’s memos in his testimony to the SFRC.107

The Chiefs were equally troublesome for Johnson. In April, Johnson warned McNamara, “Well let’s give [Wheeler] more of something. Because I’m going to have a heart attack if you don’t give him more of something.”108 Thus, when McNamara arrived in Vietnam in May, he told MACV that the main priority was winning the war and that they would have everything they needed to achieve that objective. In May 1961 and again in May 1964, for Johnson, traditional military means could achieve a “winning” formula, something neither McNamara nor even Maxwell Taylor recommended.109 Even though he described the Chiefs as “fools,”110 in April 1964, Johnson asked McNamara if he had “anybody [who] has a military mind that can give us a military plan for winning that war.” This represented a break in policy on Vietnam because until this point the Chiefs had very little say in designing policy.111 A recording on April 30, 1964, is particularly revealing in this regard. Johnson indicated that “What I want is somebody that can lay up some plans to trap these guys and whoop hell out of them, kill some of them, that’s what I want to do,” to which McNamara responded, “I’ll try to bring something back that’ll meet that objective.”112

By the spring of 1964, Johnson appeared to fall into the trap Galbraith had warned of in the spring of 1962, namely “the mystique of conventional force, and the recurrent feeling that, in the absence of any other feasible lines of action, the movement of troops might help.”113 Despite lacking an overarching strategy, McNamara’s May 1964 report and the NSC discussion that followed set the administration on a path to conventional war against North Vietnam. In reference to the overall objective to “win,” McNamara’s trip report warned that “We are continuing to lose. Nothing we are now doing will win.”114 However, in the NSC discussions, it was McCone (“we should go in hard and not limit our actions to pinpricks”) and McGeorge Bundy who argued most vehemently for planning a bombing program against the North.115 In the next days, Bundy reiterated his conviction that military planning should move forward within a “larger framework – the US national interest and the future of Southeast Asia – that I hope we will all be thinking as the discussion goes on.”116

However, Galbraith’s concern about traditional deployments of troops was also an economic one. In the key May 1964 discussions, McNamara argued that any planning for a bombing program should also involve an information program for the public and Congress, who would ultimately have to fund expanded operations. Rusk argued that doing so could put the President in a “precarious position.”117 Again in June 1964, McNamara suggested to Johnson that “many of us agree” that “if we’re going to go up the escalating chain, then we’re going to have to educate the people Mr. President and we haven’t done so yet.” Johnson refused, remarking, “They’re going to be calling you a warmonger.”118

Nevertheless, at Johnson’s request to have “a military mind” give “a military plan for winning the war,” McNamara led a meeting in Honolulu in June 1964 with CINCPAC and MACV commanders where the full range of military plans and contingencies was considered. These included the use of tactical nuclear weapons, the deployment of ground troops and the first version of a JCS list of 94 targets that would become a major bone of contention between civilians and the military. On the basis of that list, McNamara began planning for a graduated escalation bombing program.119 Economists such as Thomas Schelling, who was an old friend of McNaughton’s dating back from their work on the European Payments Union and then at Harvard University, provided the intellectual rationale for a progressively escalating bombing campaign. In theory, bombing would signal to North Vietnam that the United States was serious about preserving an independent South Vietnam and thus induce them to reduce their infiltration and opt for negotiated settlement. Crucially, it promised maximum civilian control and the greatest economy of effort each step of the way, precluding the need for the deployment of ground troops.

The notion of tying air strikes to a political settlement had gained traction since McNamara’s last two trips to Vietnam. The idea, at first, was to send messages to Hanoi through the nominally independent commission in charge of overseeing the Geneva Accords in Indochina, which included representatives from Canada, Poland and India. In December 1963, McNamara’s notes of a meeting with Harkins and Lodge included the following comment: “associate the plan with the warning to the NVN [North Vietnamese] thru the Pole (stop or we will hurt you),” and in March 1964, McNamara’s questions included “if the escalation track is chosen, could we start with recon over North Vietnam Laos [and] move to negotiation in an international body at every step.”120 In May, Lodge, who had been pessimistic about the prospects for negotiation, had come around to the idea that “strikes against the North coupled with the Canadian gambit” might be the key to success.121 As a result, about two weeks after McNamara met with his military advisors in Honolulu, the Canadian ICC Commissioner, Blair Seaborn, went to Hanoi to convey the message that “the US public and official patience with North Vietnamese aggression is growing extremely thin.”122

For McNamara, therefore, military planning was aimed at inducing political not military or battlefield outcomes. Military advisors were not, therefore, relevant to decision-making. President Johnson and McNamara’s differing views about the proper role of military authorities was particularly evident where staffing in South Vietnam was concerned. In June 1964, when General William Westmoreland replaced Harkins, discussions turned to replacing Ambassador Lodge as well. President Johnson favored Taylor, suggesting that “Taylor can give us the cover we need with country, conservatives and Congress.” McNamara tried repeatedly to stall Taylor’s selection by suggesting George Ball as his “first choice.” He also proposed Gilpatric, McGeorge Bundy and even himself. Echoing complaints that had followed the creation of MACV in the spring of 1962, McNamara worried that Taylor’s selection would spark criticism that the administration was “putting [Vietnam policy] in the hands of the military” and that there were inherent “problems with a military man.” Rather than respond to the substance of McNamara’s criticism, Johnson curtly dismissed it, saying, “Well that’s what it is.”123

Johnson was ultimately more interested in political cover than in making any substantive decisions about Vietnam. Events worked in his favor. In June, the Republican party confirmed the arch-conservative Cold Warrior Barry Goldwater as its presidential candidate. Casting the Republican senator as a dangerous extremist, Johnson sought to mollify both sides of the aisle. He thus delayed key decisions and moved to a holding pattern that would demonstrate toughness and moderation in equal measure. In August, a series of naval incidents in the Bay of Tonkin provided just the opportunity to get bipartisan support behind his ambiguous policies. On August 2, North Vietnamese vessels attacked the destroyer USS Maddox. Taylor argued for a strong response. None came as McNamara cautioned that the event was not significant militarily, that “Taylor [was] over-reacting” and that it was not clear that the attacks had been intentional.124 Moreover, on August 3, he told the President that the actions had likely been a defensive response to US and South Vietnamese recent covert operations in the area, the “plausibly deniable” actions the administration had stepped up in the preceding months.125

However, the following day, the Maddox and another destroyer, the Turner Joy, reported further attacks. Almost immediately, the OSD began receiving reports that “freak weather events” and “overeager sonarmen” might have produced false reports.126 In an NSC meeting on August 4, some advisors worried that the administration might be accused of “fabricating the incident.” McCone unambiguously stated that North Vietnamese actions had been defensive. Unmoved, Rusk concluded: “An immediate and direct reaction by us is necessary. The unprovoked attack on the high seas is an act of war for all practical purposes. We have been trying to get a signal to Hanoi and Peking. Our response to this attack may be that signal.”127 Ultimately, before the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin had settled, the State Department prepared a draft congressional resolution and presidential speech, which argued that the administration should receive bipartisan support for retaliatory and “defensive” actions. McNamara and Rusk led a flurry of congressional outreach efforts to convince both sides that the actions envisaged would meet their preferences. To conservative senators, McNamara shared intelligence that the North Vietnamese were likely responding to recent attacks and insisted the military would have all they needed; to liberal senators, he insisted on the limited character of the response. Tracing a moderate path, Johnson explained to the American people that he had been compelled to respond, that his actions demonstrated “firmness” and were “limited and fitting” as he launched Operation Pierce Arrow, the retaliatory air attacks over North Vietnam.128

By August 10, Johnson signed the Tonkin Gulf resolution into law. Only Senators Morse and Ernest Gruening dissented. Congress, the resolution read, “approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”129 The resolution gave the President free reign in Vietnam. It was a political masterstroke, a “tribute to the Secretaries of State and Defense” as Johnson put it. By lunchtime on August 10, Johnson concluded that it was now time for the administration to take the initiative in Vietnam and “asked for prompt study and recommendations as to ways this might be done with maximum results and minimum danger.”130

The August incidents and the ensuing resolution produced several important outcomes for the Johnson administration and thus for McNamara. First, it provided Johnson with official bipartisan support around one of his most politically troublesome foreign affairs problems, enough to carry him through the election. However, in conducting air strikes over North Vietnam, the administration inadvertently opened floodgates. The pressures to continue bombing and to escalate further in Vietnam with every fresh incident grew steadily. With less congressional pushback, the administration spent the rest of the year planning for the military escalation that would come in 1965.

In November, William Bundy headed a new interdepartmental committee that, together with McNaughton, spelled out options for Vietnam that would essentially frame the debate for the next year. Option A involved “present policies indefinitely” with no US-led negotiation track. Option B, the “fast squeeze,” added “fairly rapid” military moves in support “of our present objective of getting Hanoi completely out of South VN [Viet Nam] and an independent and secure South VN reestablished.” Option C, the final “progressive squeeze and talk,” promised a “steady deliberative approach” of “graduated military moves” with negotiations in mind; but, rather ominously, these “would have to be played largely by ear.”131 Only the recently promoted Chairman of the JCS Wheeler defended Option B to McNamara. Option C, in all its vagueness, therefore became the reasonable policy.132

The administration prepared to escalate despite widespread misgivings. McNamara noted, “Dean [Rusk] believes the harder we try and fail the worse we are hurt.”133 McNaughton, despite similar concerns that he shared privately with Forrestal, who was preparing to leave, questioned the shift toward a deepening commitment in Vietnam when there were “clear indications of the inability of the South Vietnamese to defend themselves.”134 Still, a policy of self-help was no longer viable and decisions loomed. While McNaughton, and indeed Senator Russell, argued that Khanh’s lack of cooperation and South Vietnamese weakness might provide a front for withdrawal, the option was widely rejected. Although they began to consider options for the deployment of ground troops, neither McNamara nor Taylor believed they were a good idea. Where before Westmoreland and others had argued that a stable government in South Vietnam was a precondition for initiating a more sustained bombing campaign, that it would divert resources and attention from the more pressing problems on the pacification front, both McNamara and Taylor now felt that military actions might offer a “glimmer of light” to the South.135

Instead, as would become even more pronounced in 1965, bombing promised a controllable and economical alternative to the deployment of troops, a more palatable route than the other options presented and a policy where a consensus could hold. Although McNamara did not envisage going after the JCS’s full ninety-four targets, he nonetheless cultivated ambiguity to keep them in line. As he conferred with them about further retaliatory moves, he wrote to the President that they “consider this first step towards attack on the 94 target list; if no action, most chiefs feel should withdraw from South Vietnam.”136 The President’s response was appropriately vague: “say to chiefs we are reaching a point where our policy may have to harden – don’t want to start something we can’t finish, and in agreement there must be retaliatory actions that are swift.”137 On the civilian side, others worried about the efficacy of the bombing: “the problem is the need to convince military leaders (and not only on the GVN side) that gimmickry and technology are not decisive. For example, air power can be most helpful if properly used but can also be counter-productive,” one member of the Vietnam Working Group complained.138 Whatever consensus existed, therefore, was forced and relied on ambiguity. It failed to clarify objectives and left basic questions over strategy unanswered.

The transition to the Johnson administration marked a change for McNamara. The new Commander-in-Chief had little interest for counterinsurgency and preferred options that conveyed toughness. He felt less constrained by some of the economic issues that had weighed on Kennedy. He therefore was more open to considering traditional military tools. By 1965, all the advisors that had advanced the underlying rationale for pacification programs in Vietnam had left. For all intents and purposes, counterinsurgency ideas would not resurge for another two years. At the same time, with each successive coup in South Vietnam, the situation worsened, and with it, the policy of self-help became increasingly tenuous. The planning for withdrawal was swiftly dropped, but McNamara continued to maintain the veneer of a US commitment that was limited to assistance long after he and his colleagues had concluded that South Vietnam would collapse without direct US involvement. In just a few months, McNamara canceled the plans that he had carefully developed between July 1962 and the fall of 1963. He did so because of his definition of his job: he saw himself less as a strategist and more as a resource allocator, someone who could align plans and resources to a strategy set out by the State Department and the President. When the “strategy” changed, so too did planning in the OSD.

More than anything, 1964 was a year where the Johnson administration sought to delay difficult political and military decisions. In an election year, the onus was on identifying military actions in Vietnam that were deniable or covert and that would avoid domestic reactions. Johnson was most interested in placating sources of dissent, be it Lodge, the Chiefs, liberal critics from his own party or fiscal conservatives from both sides of the aisle. As a result, McNamara was sent on successive trips to Vietnam for public relations purposes and to do as he had in the fall of 1963, namely enforce a consensus and thus minimize politically damaging discord. The Tonkin Gulf incidents occurred at a time when the administration had already decided to do “something” militarily. The resulting congressional resolution gave the administration the breathing space to consider military options more freely. By 1965, Johnson had decided to act militarily but he now delayed economic decisions. It was Johnson’s failure to contend with economic factors that would strain McNamara’s relationship with the President to breaking point.