By 1965, the administration was primed to make military moves in Vietnam. Johnson’s landslide electoral victory in his own right had strengthened his place as Commander-in-Chief, and the Tonkin Gulf resolution, as McNamara observed, gave him “a blank check authorization for further action.”1 In relatively quick order, between January and July 1965, troop numbers increased, and their mission changed. At the start of the year, 23,300 “advisors” were present in Vietnam. A month later, the graduated bombing campaign Operation Rolling Thunder began with a first deployment of Marines just a few weeks later. By April, troops – no longer advisors – numbered over 60,000. The first combat unit, the 173rd Airborne Brigade, arrived in May. And in June and July, McNamara increased the troop ceiling to 120,000 then 175,000 men. The year ended with more than 184,000 US troops in Vietnam and plans for a troop increase to 400,000 in the following year and a further 200,000 the year after that.

Each of these increases reflected unsatisfying compromises and a built-in momentum of military escalation. Johnson chose escalation in Vietnam but ignored the domestic and economic implications of those decisions. For a time, McNamara thought he could plan for escalation without damaging his own ambitions in the defense department or the US economy. By July, he felt otherwise. As the troop numbers and US responsibilities in South Vietnam expanded, McNamara argued for calling up the reserves and for a budgetary realignment. His advice went unheeded and the first rupture in his relationship to the President emerged. Furthermore, McNamara supported incremental increases in troops and air sorties even though he had little faith in their chances of military success because he believed that negotiations would be forthcoming and that the war would therefore be short. The illusion of civilian control gave way to the reality that war has a momentum of its own. The notion that the war would be short-lived gave way to the reality that the administration had no realistic outcome in mind and no appetite for political dialogue with the North. By the fall, McNamara considered leaving.

The documentary record largely validates Johnson’s prediction that McNamara would be judged as a “warmonger,” the architect of the decisions to escalate in 1965. However, as his colleagues at the OSD cautioned, McNamara’s written record is problematic and, in some ways, misleading. Daniel Ellsberg, who rejoined the Department of Defense in 1964 as McNaughton’s special assistant, explained that memoranda in the OSD were written and marked as “drafts” on the understanding that “other people could see them; that they could be leaked,” that they were primarily designed to provide “talking points” even if the drafter thought it was “terrible idea.”2 McNamara countered Johnson’s accusation that his colleagues at the OSD were leaking information by boasting that virtually everyone in his department was “in the dark” over decisions in Vietnam.3 The written record, therefore, is incomplete by design. Unbeknownst to McNamara, McNaughton, who as the war escalated became his point man on Vietnam and one of his few confidants, kept secret diaries. Together with the recordings of Johnson’s phone conversations with McNamara, the diaries provide a glimpse into McNamara’s private thoughts at this key juncture in the Vietnam War and in his career as Secretary of Defense.

As he saw it, McNamara’s job was to loyally defend the administration’s policy and precluded a role in articulating strategy. PPBS, DPMs and all his innovations at the OSD were explicitly designed to plan for force requirements in support of a strategy articulated in the White House or the State Department. From a bureaucratic perspective, if strategy is the broader articulation of the objectives to be achieved by the application of military force, a theory on the use of those forces, according to McNamara’s view of the bureaucratic process, should have come from the State Department and White House. His role as Secretary of Defense was to think about tactics, namely translating strategy into a series of military exchanges in the cheapest possible way and in a way that guaranteed maximum civilian control. As he explained in an oral history for the OSD, the Secretary of Defense’s role was only to “comment on the military implications.”4 This definition of his job underpinned each of his recommendations in 1965.

McNamara and all of President Johnson’s senior advisors understood that 1965 would be a time for decision (see Figure 8.1). In January 1965, McNamara and McGeorge Bundy wrote to President Johnson that defeat in Vietnam was inevitable unless the United States used military power “decisively” or “deploy all our resources along the track of negotiation.”5 However, using the same economic rationale that had underpinned the CPSVN, McNamara resisted deploying ground troops: it would be difficult to fund through the MAP and it would put new strains on the balance of payments at a time when the situation was improving. Even while he supported acting “decisively,” McNamara pushed back on the JCS and McGeorge Bundy’s suggestion for “larger US forces” because of what he called their “general heaviness.”6

Figure 8.1 President Lyndon B. Johnson (left) and Secretary of Defense McNamara (right) drive at the LBJ ranch, December 22, 1964.

In spite of McNamara and others’ recommendations, Johnson avoided grappling with the economic consequences of his decisions on Vietnam. He avoided trade-offs that might have prevented the inflation and international monetary crisis that Vietnam caused. Just as counterinsurgency advisors who influenced strategy departed in 1964, so too did key advisors on the economic front, chiefly Treasury Secretary Dillon, who, in March 1965, submitted his resignation. From the outset, Dillon had been unimpressed with the new Commander-in-Chief’s command of economic issues. Dillon warned that cooperation from allies and the private sector on sustaining the dollar’s role under Bretton-Woods system required assurances that the administration would not export inflation and thus would keep an eye on spending and on its balance of payments. Unlike Kennedy, Johnson often refused to return Dillon’s phone calls as colleagues warned that the President was “usurping” the Treasury Secretary’s role.7

In February, economic and military issues were heightened and intertwined. In the span of just a few days, the course of the US war in Vietnam changed as did the tenor of transatlantic cooperation on international monetary issues. On February 1, Johnson referred to the prospect of devaluation during an impromptu exchange with the press. Seething from previous experiences where he had noted the President’s “confusion” on economic matters, Dillon reprimanded White House staff that “talk makes everything worse” and offered to provide Johnson’s assistant Bill Moyers “a paper which I published last spring which reflects my detailed thoughts.”8 When the President’s off-the-cuff statement appeared in the Wall Street Journal on February 4, Dillon wrote to the newly appointed Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers that a “change in the price of gold” was not “acceptable or proper.”9 On the very same day, de Gaulle convened a press conference where he attacked the role of the dollar in the Bretton-Woods system and suggested a return to the gold standard. France’s previous cooperation on international monetary issues came to an end and Dillon’s departure exacerbated the feeling in Europe and elsewhere that the Johnson administration would not exercise fiscal restraint.

Nevertheless, in response to de Gaulle’s presentation, McNamara and Johnson went on the offensive to prove that the administration was, in fact, still dealing with the balance of payments deficit. In a statement to Congress, Johnson unequivocally rejected devaluation and, with transatlantic cooperation now in doubt, proposed new measures to curtail private capital flows. He rebuffed de Gaulle and said, “Those who fear the dollar are needlessly afraid. Those who hope for its weakness, hope in vain.”10 On a parallel track, McNamara spoke to a group of bankers and business representatives at the White House. Using data from his recent annual report on the balance of payments, he projected a reduction of defense expenditures that impacted the international balance of payments from their peak of $2.8 billion in 1961 to a projected $1.25 billion in 1967. He explained that efforts from preceding years were beginning to “take shape,” including the Defense Department’s use of local forces and “thinning out” of overseas deployments.11

In Vietnam, however, the scene was set for an increased deployment and the implementation of military plans that had been designed in 1964. On February 7, the US base of Camp Holloway in Pleiku was attacked. McGeorge Bundy, who was in Vietnam, encouraged Johnson to move forward on more aggressive measures. Over the next week, with fresh Viet Cong attacks in South Vietnam and after a first series of US reprisal air attacks, Johnson approved Operation Rolling Thunder. Where previous bombing raids were designed to retaliate, now their purpose was to punish and bring “sufficient pressure to bear on the DRV to persuade it to stop its intervention in the South.”12 During a series of NSC meetings, McNamara supported this sustained bombing campaign. Wheeler remarked, “The secretary of defense is sounding like General LeMay. All he needs is a cigar.”13 The administration also finally released the Jorden Report and began planning for the deployment of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, which had been activated in the aftermath of the Tonkin events. Ostensibly deployed to carry out “active defense” of the US base in Da Nang, the Marines landed in March. In a moment of great symbolism, the President canceled a planned meeting on the balance of payments to make room for an NSC meeting on Vietnam.14

Johnson’s military and civilian advisors never agreed on the bombing program’s central objectives. In South Vietnam, they included lifting morale, curtailing infiltration and supporting the ground campaign. Where North Vietnam was concerned, they were designed to “communicate” and induce the North’s representatives to come to the negotiating table. In Washington, they were intended to do “something” that played to US technological advantages and minimized both the chances of domestic upheaval and the prospect of a military confrontation with the Soviet Union or China. In April, DCI McCone resigned in anger after unsuccessfully lobbying for a more aggressive bombing campaign even as he was censoring CIA reports that McNamara also read and which questioned the effectiveness of any bombing program.15 For the Joint Chiefs, a bombing campaign was a step in the right direction. John McConnell succeeded LeMay as Air Force Chief of Staff. Like the other Chiefs who were all gradually replaced under McNamara, McConnell lacked the military clout of his predecessor and was more willing to get behind Wheeler’s efforts at glossing over disagreements and discomfort in the services to produce common JCS positions that fit within the civilian advisors’ parameters.16 The Chiefs therefore supported the administration’s bombing campaign despite their discomfort and reservations over its military value.

McNamara’s support of the bombing program fit with his own priorities and philosophy at the Department of Defense. It promised a creative and civilian-controlled substitute for the introduction of ground troops. With pressure building to do “something,” Taylor and McNamara questioned the suitability of “white-faced soldiers” as they both tried to preempt deployments of ground troops. McNamara never believed that bombing alone would end the war nor that it would do very much to solve the central problem of guerrillas in the South. For him, Operation Rolling Thunder was not designed to produce military outcomes but to “signal political resolve” to the North and thus encourage a political settlement. McNamara also believed the bombing program would limit the budgetary impact and domestic repercussions of escalation. Bombing, instead of MAP-dependent programs, would obviate the need for the type of expensive and “heavy” defense installations that had weighed down the balance of payments. Crucially, bombing would draw more readily on the armed services’ budget and, in so doing, hide the financial costs of escalation.

However, as the administration increasingly drew on the services’ budgets, the SASC rather than the SFRC took on a greater role in overseeing policy. A major constraint on funding for Vietnam was thus removed. Chairman of the SASC Russell was determined that the services have all the resources that they needed despite his misgivings about the Vietnam commitment. As presaged in Vinson’s exchange with McNamara in 1964, the SASC’s charge that McNamara was shortchanging the services tilted the balance of power toward the Chiefs and increased pressure on civilian decision-makers to give them more of “something.” On March 1, 1965, just under a year after planning for withdrawal had been suspended and, with it, pressures to decrease funds allocated to Vietnam, McNamara wrote to the Chiefs: “Occasionally, instances come to my attention indicating that some in the Department feel restraint imposed by limitations of funds. I want it clearly understood that there is an unlimited appropriation available for financing aid to Vietnam. Under no circumstance is lack of money to stand in the way of aid to that nation.”17

Despite McNamara’s promises of “an unlimited appropriation,” the SASC understood that McNamara’s budget was undervalued and that it relied on problematic assumptions. In his testimony to the SASC, McNamara admitted that he used “somewhat arbitrary assumptions regarding the duration of the conflict in Southeast Asia,” namely that the war would end, as if by magic, by June 30 of each given fiscal year.18 He then submitted supplemental requests to make up the difference. Ironically, one of McNamara’s greatest contributions to the defense budgeting process was to extend time horizons to better capture the full costs of defense programs and operations. In Vietnam, he did the opposite. He then used his authority as Secretary of Defense to create new channels for additional funds, including submitting supplemental requests to Congress and creating an “Emergency Fund, SEA,” which was specifically earmarked for the services’ production and construction needs. The first supplemental request specifically for Vietnam passed in May 1965 for $13.1 billion, most of which McNamara had known he would need when he first presented the FY65 budget in December 1963, while his request for the Emergency Fund, SEA, was submitted in August 1965.19

In a further manipulation of the budgetary process, McNamara drew on the services’ operating budgets and existing resources. He avoided stockpiling equipment as had been done during the Korean War and instead relied on existing services’ stocks. He calculated ammunition costs based on past usage even as operations increased and were projected to increase further. Using this technique to provide support to forces in the field drew the costs of operations in Vietnam from the services’ normal operating budgets.20 McNamara’s creative accounting eventually became a focal point for congressional anger over the administration’s policies in Vietnam because it had blurred the costs of operations in Vietnam.

Moreover, as the Vietnam War escalated, McNamara accelerated cost-saving measures elsewhere. This kept the overall defense budget down and allowed the administration to continue to preserve a pretense of fiscal responsibility. He accelerated the base closure program at home and abroad and instituted new programs aimed at greater cost-effectiveness within the Department of Defense. Crucially, as part of a broader program aimed at either delaying and canceling expensive new programs and procurement decisions for the FY66 budget, McNamara explicitly embraced a nuclear posture based on MAD in March 1965. The idea that existing stocks of nuclear weapons were sufficient to prevent a nuclear confrontation preempted a growing chorus for an anti-ballistic missile (ABM) program, which McNamara believed was “massive, costly” and likely ineffective.21

For a time, McNamara’s accounting gimmicks and cost-saving measures largely avoided a politically charged debate about the potential inflationary effects of spending on Vietnam. In June 1965, the Great Society legislation passed, as did a further tax cut. But McNamara’s creative bookkeeping was inevitably a short-term solution. It could be sustained only if the war was brought to a swift end or if the budget was adapted to the reality that the United States was in fact fighting a “war” in Vietnam.

During the first months of 1965, McNamara believed a bombing program would be relatively inexpensive and induce a political solution to the problems in Vietnam and thereby prevent the introduction of ground troops. Although the first deployment of Marines had landed in Da Nang on March 8, in a conversation on March 30, McNamara warned the President against the recommendations coming from the Chiefs to send additional forces for purposes other than defense. He explained that Taylor believed that ground troops would have “great difficulty” in a “counterinsurgency role” and concluded that “Our troops, while admirably trained, are poorly trained as counter-guerrilla.”22 He also warned that the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces could match increases in South Vietnamese and US forces. In spite of this, the administration planned for additional troops in more offensive roles. Johnson remarked: “I don’t think anything will be as bad as losing and I don’t see any way of winning but I would sure want to feel that every person who had an idea, that his suggestion was fully explored.”23 Unfortunately, alternative plans that were politically palatable to Johnson and militarily feasible did not emerge.

Instead, various advisors and agencies played down the risks behind the introduction of ground troops. They argued that the United States could play to its distinct advantages and thus avoid a similar experience to the French. The Air Force thought that existing airlift capabilities could vastly increase mobility and thus change the traditional ratios of forces needed to defeat an insurgency. Later, Lodge, too, who would return to Vietnam in the summer of 1965, was optimistic about the United States’ naval power: “We don’t need to fight on the roads,” he explained, “We have the sea.” Lodge “visualized our meeting Viet Cong on our own terms,” and added, “We don’t need to spend all our time in the jungles.”24 The problem, as McGeorge Bundy warned, was quite simple: “I see no reason to suppose that the Viet Cong will accommodate us by fighting the kind of war we desire.”25

In March, McNamara and his colleagues at the OSD became increasingly uncomfortable with the shifting sands on Vietnam. McNaughton was sent to Vietnam to study the JCS recommendations to deploy three divisions and step up air raids to deal with a “bad and deteriorating” situation. McNaughton returned from Vietnam with an updated version of his three options. To McNamara, he wrote that policy was “drifting” and warned about the lack of clear objectives and tendency within the US government to discount options “between ‘victory’ and ‘defeat.’” He candidly spelled out the objectives of the US presence in Vietnam, which he quantified as 70% “to avoid a humiliating US defeat,” 20% to prevent Chinese domination of the country and region and only 10% to guarantee “a better, freer way of life” in South Vietnam. He added that they also included “to emerge from the crisis without unacceptable taint from the method used” and “not – to ‘help a friend.’” He laid out the central paradox of growing US involvement in Vietnam: on the one hand, the “main aim” was strengthening South Vietnam; on the other, planned efforts would “probably fail to prevent collapse.” The key objective, therefore, if the United States could not effectively organize a viable pacification program, was to negotiate a way out and ensure that if and when South Vietnam did collapse, the United States emerge as a “good doctor,” its international credibility as unharmed as possible.26

Within a month, however, McNamara himself went to Vietnam and Honolulu and returned supporting the deployment of 82,000 troops, suggesting they would “be effective against the Viet Cong and would release ARVN forces for more distant operations.”27 This number was less than the JCS recommended and more than Taylor wanted. It flew in the face of his own trip notes where he and many of the advisors worried about the dangers inherent to introducing US troops, the continuing poor standards in ARVN forces and the South Vietnamese government’s inability to date to “consolidate its political bases in the countryside.” He projected that troop numbers would go up to 270,972 in a second phase with the United States adopting increasingly offensive roles.

McNamara also supported expanding the bombing program, although its value was in doubt. His military advisors had indicated that it had had little effect on infiltration and the State Department concluded that “over-eagerness” for negotiations would be “counter-productive and self-defeating.” For McNamara, the bombing program was meant to reduce infiltration and spur negotiations, yet McNamara was now defending bombing to “convince Hanoi authorities that they cannot win,” and added that “It is the creation of this frame of mind which will finally end infiltration.”28 He presented some of his concerns and doubts to Johnson and warned that bombing “cannot be expected to do the job alone” and that it would not constitute a strategy for “victory.” Nevertheless, he defended the program on “psychological” and “physical” grounds.29

Although the theory of graduated pressure was aimed at encouraging negotiations, Johnson had no appetite for them. In April and May, he rejected British and UN attempts at mediation and only grudgingly accepted McNamara’s suggestion to pursue a bombing pause in May with a view to kick-start negotiations. Johnson was uncomfortable with the bombing pause because he did not believe North Vietnam was prepared to negotiate in good faith. The fact that Robert Kennedy had privately lobbied for the pause did not help and Johnson disdainfully referred to it as “Bobby Kennedy’s pause.” The pause lasted less than a week and bore no results. The President felt vindicated and told McNamara, “I would say to Mansfield, Kennedy, Fulbright that we notified the other people – and for six days we have held off bombing. Nothing happened. We had no illusions that anything would happen. But we were willing to be surprised … No one has even thanked us for the pause.”30

Similarly, a brief renewed interest in pacification in the spring and summer of 1965 was political cover for the administration’s escalation against growing domestic criticism from the left, including from “Mansfield, Kennedy and Fulbright.” In April, Johnson spoke of a Tennessee Valley Authority–type of economic development program for Southeast Asia and sparked a renewed interest in economic and social development programs in Washington. In the weeks before Johnson’s speech, McNamara had responded to SFRC criticism of the US posture in Vietnam. To Senator Morse, one of the two holdouts from the Tonkin Gulf Resolution and an increasingly vocal critic of Vietnam, McNamara defended the MAP program role in guaranteeing a “minimum risk of United States involvement in local wars along the far-flung frontier of freedom.”31 Lodge returned to Vietnam in August 1965 together with Edward Lansdale with a mandate to refocus attention on pacification. While McNamara and McNaughton continued to argue that the solution to the problems in Vietnam were rooted inside South Vietnam, for the administration, pacification efforts never amounted to much more than public relations.

The way Johnson framed discussion in March and April 1965 explains the break between McNaughton and McNamara’s private doubts and their public support of escalation. First, Johnson had grown increasingly frustrated with his advisors and policies in Vietnam, which seemed either politically impractical or doomed to fail. He chastised McNamara, Rusk and the Joint Chiefs and said that he was “tired of taking the blame.”32 McNamara stepped in because, as he told Rusk, “someone has to make a decision.”33 Second, Johnson influenced the administration’s decision to downplay changes in policy. McNamara understood that the program he was proposing marked a qualitative and quantitative shift. He recommended that the administration reach out to congressional leaders about the changed mission. Johnson overruled him to avoid a public debate.34

The origins of McNamara’s eventual disillusionment with the war were rooted in the early months of 1965 and became more acute in the follow-up decisions of July. Insofar as McNamara viewed the role of Secretary of Defense as a resource allocation function, he was concerned with the looming gap between the administration’s growing commitment in Vietnam and in its inability to rally the domestic resources to sustain the expansion. His falling-out with the administration also hinged on what he considered to be a lack of an overarching strategy with a clear end point that would justify escalating costs within the DOD. In March 1965, while Johnson praised the “psychological impact” of sending the Marines rather than the “Sunday school stuff” that had preceded it, McNamara complained that the administration needed a clearer plan and should “be less rigid about talks.” He used similar language to McNaughton’s and told Johnson, “My sense is that we’re drifting from day to day and we ought to have inside government what we’re going to say tomorrow and then next week.”35 Although he complained about the lack of strategy, he did not step in to fill the void.

When bombing failed to achieve a quick political solution, McNamara hoped a more significant escalation might. In a later oral history interview, McNamara remarked that one key lesson that he had learned from the Bay of Pigs disaster was that the United States should “not move militarily except with massive force in relation to the requirement; and then that massive force [should be] controlled with utmost care and restraint.”36 This seems to have been his position in June and July when Westmoreland requested additional troops. McNaughton and McNamara prepared a series of draft reports that culminated in Johnson’s July 28 press conference announcement that ground troops in Vietnam would increase to 125,000 men. Some months later, McNaughton wrote in his diaries: “Bob was a ‘B’ man (fight hard and bargain out); I said I was a ‘C’ man because our chemists won’t permit ‘B’ (‘C’ is to withdraw, seeking the best possible cover for it).” He added that Rusk was an ‘A’ man: “make the enemy back down.”37

In his first draft report in June, McNamara argued that the United States should either escalate decisively or get out. If it chose to escalate, he recommended increasing troops to 200,000, mobilizing the reserves and expanding the air campaign, including mining North Vietnamese harbors while intensifying diplomatic efforts. The United States would henceforth take over lead responsibility for fighting the war in the South and the North and, the logic went, force Hanoi to the negotiating table or at least encourage a more favorable settlement.38 Reaction to the report was immediate, none more so than from McGeorge Bundy, who described it as “rash to the point of folly.” Bundy echoed earlier comments that both McNamara and McNaughton had made when he challenged the assumptions underlying McNamara’s recommendations: troop increases “untested in the kind of war projected,” increased bombing “when the value of air action we have taken is sharply disputed” and a naval quarantine “when nearly everyone agrees the real question is not in Hanoi, but in South Vietnam.”39

Bundy’s comments beg the question: by taking a more aggressive stand, had McNamara suddenly overcome all his doubts or did he instead feel compelled to don more hawkish views within the administration to force the notion of incremental increases to a logical conclusion? That McNamara would reject all his previous concerns to support the introduction of large-scale ground troops, an option he had consistently resisted up to this point, is improbable. That he would suddenly share Westmoreland’s views was similarly doubtful.

Instead, as escalation loomed, the OSD took a more active role in overseeing operations in the field. McNaughton, with Wheeler’s special assistant Andrew Goodpaster, had started to study existing estimates of what the United States might have to do to win in Vietnam. Another McNamara confidant, Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance, had set up a number of working groups on Vietnam. Crucially, Alain Enthoven at the Office of Systems Analysis became involved on Vietnam for the first time. Enthoven later explained that the idea behind his work was that by systematically analyzing data, the OSD could “forestall the over-Americanization of the war, the pervasive optimism of official estimates on how well we were doing and the twisted priorities that developed in the expenditure of billions of dollars.”40 McNamara and Enthoven would later become infamous for their reliance on metrics to assess operations in Vietnam. At the time, however, the Secretary of Defense was reacting to the paucity of reliable estimates from the field. Westmoreland often relied on anecdotal evidence and “instinctive” recommendations and projections. This frustrated McNamara as progress failed to materialize.41

By better quantifying the costs of the troop deployments, McNamara could also force the civilians involved in decisions to consider their economic implications and to confront the in-built momentum of troop increases. Each incremental troop introduction created fresh needs for more troops. General Krulak, who had been reassigned to oversee the logistics of the Marines in the Pacific, had reacted angrily to Westmoreland’s increases in Navy deployments in March 1965. He argued that their deployment to Phu Bai airbase had more to do with the Army’s investment in a communications facility in the area, a central component of Westmoreland’s request for additional troops, than it did with military practicalities. In his words, “dollar economics wagged the tail of the military deployment.”42 As troops were deployed, and new programs set up, their security and logistical needs expanded as well, rapidly ballooning the numbers and costs of US personnel in the country.

For the OSD, the key difference between McNamara’s first draft and Johnson’s announcement was on the issue of aligning resources to new commitments. With Enthoven and Vance, McNamara agreed that the planned escalation would have to include a publicity campaign and “felt that we should make it clear to the public that American troops were already in combat.”43 Instead, Johnson said the United States was fighting a “different kind of war.”44 The OSD advisors also recommended calling up the reserves and national guard, extending tours of existing troops, increasing draft calls and submitting a substantial budgetary supplement to Congress. McNamara reached out to John C. Stennis, the Chairman of the Defense Subcommittee in the Appropriations Committee, to prepare him for the eventuality.45 In private, the OSD advisors felt that a tax increase would now become inevitable, and Vance referred to the 1961 Berlin Crisis when Kennedy had considered a temporary tax to offset potential inflationary pressures of increased defense spending.46 These measures were never taken.

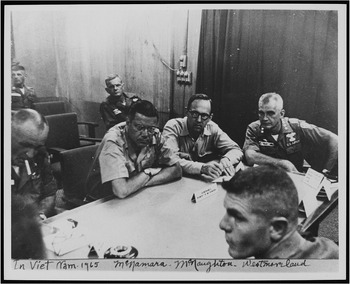

McNamara later suggested that the only time he openly disagreed with Johnson was on these key budgetary decisions made in July. He could not argue otherwise: where previous disagreements were smoothed over in private, in this instance, the President quite publicly overruled him. On July 15, McNamara had been sent on another performative trip to Vietnam to rubber-stamp the decision to escalate (see Figure 8.2). In Saigon, he heard from Vance that Johnson had decided not to ask for supplementary funds, and although Johnson initially accepted a reserve call-up, he reneged on this too within a few days. Johnson publicly talked of being at war but refused to put the domestic economy on a war footing for political reasons. In the absence of congressional support, the President did not seek a tax increase. He worried that the upcoming Medicare bill and Voting Rights Act would be compromised if a “war psychosis” took hold.47 Bundy and Rusk likewise worried that such moves would “elicit drama” at home and abroad and argued that the administration should downplay the change in policy.48 As a result, Johnson recommended that McNamara use his transfer authority – in other words, drawing from resources elsewhere in the defense budget – and seek supplemental funding only in January after the administration’s domestic legislative agenda had passed.49

Figure 8.2 Secretary of Defense McNamara (left), John T. McNaughton (middle) and General Westmoreland (right) listen to a briefing in Saigon, Vietnam, July 1965.

The final July report and ensuing decisions represented an uncomfortable blend of policies that were aimed at producing a compromise and consensus, but which satisfied no one. They did not go as far as Westmoreland’s initial recommendations and went too far for its critics. Although McNamara wrote that the war was entering a conventional phase where the United States could “seek out the Viet Cong in large scale units,” to the Joint Chiefs, he drew on CIA reports to argue that this was “highly improbable.” Wheeler argued for more offensive actions while he admitted that the “lack of tactical intelligence” might impede their effectiveness.50 As he was wont to do, Johnson relied on advisors who did not have access to the full body of intelligence on Vietnam to validate his decisions. He convened the “Wise Men,” a group of prominent figures that included John McCloy, Dean Acheson and Robert Lovett, who encouraged him to act decisively in Vietnam.51 McNamara grew increasingly irritated with Johnson’s reliance on external advisors like the “Wise Men” who often encouraged the President to disregard the OSD’s concerns.

The problem was also that alternatives were not presented to a President who wanted to act militarily in Vietnam but also wanted to avoid international or domestic consequences. Arguably, no policy that could satisfy Johnson’s competing objectives existed. The JCS took a full month to submit their “Concept for Vietnam.” It dismissed the theories of graduated pressure and argued instead for a far more aggressive use of military force. Similarly, George Ball, who argued that the administration should be prepared to let South Vietnam collapse, “had [his] day in court” but was outnumbered in an administration who feared the international repercussions of withdrawal from Vietnam. Johnson refuted Ball’s argument that the South Vietnamese could not win, and he jokingly remarked, “But I believe that these people are trying to fight. They’re like Republicans who try to stay in power, but don’t stay there long.”52 The concluding section of McNamara’s report offered just a hint of optimism about the path ahead: “The overall evaluation is that the course of action recommended in this memorandum – if the military and political moves are properly integrated and executed with continuing vigor and visible determination – stands a good chance of achieving an acceptable outcome within a reasonable time in Vietnam.”

The ambiguous idea of an “outcome” was itself a product of a compromise and reflected an unsatisfactory consensus about objectives in Vietnam. McNamara and McNaughton’s first drafts had talked of a “settlement” because military escalation was geared toward political negotiations. They also introduced the idea of an extended bombing pause to that effect. Lodge had suggested using the term “outcome” instead because he did not believe a political settlement was likely: “perhaps a conference between North and South Vietnam could produce something at the right time,” he thought, “when our side is strong enough, but that is doubtful too.”53 Similarly, Lodge’s Deputy U. Alexis Johnson commented that the administration should “say nothing further with respect to negotiations” and opposed the idea of a pause.54

McNamara sought a political settlement because he had little faith in South Vietnam’s ability to fight the war itself. The central dilemma of how the United States could “win” with a collapsible ally in the South was left in limbo during the July decisions. In the early months of 1965, McNamara supported the idea that the United States should wait until South Vietnam stabilized before escalating. By July, his public position had become aligned with that of the JCS, namely that escalation might provide the breathing room for South Vietnam to strengthen. In private, however, McNaughton and McNamara supported the idea of a coalition government with a Communist role in the South on the assumption that the existing South Vietnamese government would never be strong enough to survive alone.

However, McNamara merely implied this position in his statements at NSC meetings. He rejected the country team’s “more optimistic” assessment of what he termed the “non-government” in South Vietnam. Lodge argued that the United States should act “regardless of the Government” as the United States could not “count on stability in South Vietnam.”55 Although the country team noted some improvement under Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky and President Nguyen Van Thieu, McNamara estimated that they would not last the year. By early August, he made a remarkable admission: “no country in history has been victorious in battle when its central government has been weak and unstable.”56

McNamara had become the public face of an escalation that made no sense. If a military victory was impossible and if South Vietnam would not, as he believed, become viable in the foreseeable future, then a political settlement, however tenuous, was the only feasible outcome. The State Department had no appetite for negotiations, yet escalation went ahead all the same. As Secretary of Defense, McNamara understood that the United States could not escalate significantly, as it was doing, without committing resources to that end. But no publicity campaign, no reserve call-up and no tax increase occurred. Within months, even Johnson’s liberal Council of Economic Advisers worried that the administration could not push through with the Great Society programs, the war in Vietnam and keep inflation down without a tax increase.57 McNamara understood all these things in July and yet still went on record supporting the United States taking a leading role in Vietnam. In the months that followed, it would put him at loggerheads with Johnson and precipitate his decision to leave government.

During the July decisions on Vietnam, McNamara began to discreetly prepare for a life after the DOD. When he had accepted the position of Secretary of Defense, he had asked for the “closest possible, personal working relationship with the President and … [his] full backing and support so long as he is carrying out the policies of the President.”58 Had he concluded that this condition was no longer being met and that his usefulness to the President had come to an end? Was he angry about becoming a figurehead for an escalation that he did not want? Was he anxious that the piecemeal fashion in which Johnson accepted his recommendations would undermine his record of success at the DOD? The record is not clear. One of Johnson’s “Wise Men,” John McCloy, offered him the Ford Foundation presidency. He noted, “I told him I had given the matter of my future a little thought but I showed a conditional interest.”59 The job offers accelerated in the fall of 1965, including the presidency of US Steel, which sent his old mentor Tex Thornton to lobby on their behalf. The presidency of the Rockefeller and especially the Ford Foundation attracted him most. He eventually demurred: “when the Vietnam thing got so serious he had to withdraw himself from consideration.”60

McNamara was torn between his private views about the weaknesses of the administration’s policy and his conception of loyalty to the Commander-in-Chief and of the role as Secretary of Defense. Given his privileged vantage point, he understood that if the war continued, its economic costs could not be hidden indefinitely and could scuttle his objectives at the Defense Department. He had taken an oath of office where he had sworn to protect the Constitution, which included a duty to tell the truth to the Congress. And yet he could not get past his loyalty to the office of the President. As he explained in an interview given after he was fired, “Around Washington, there is this concept of higher loyalty. I think it’s a heretical concept, this idea that there’s a duty to serve the nation above the duty to serve the President, and that you’re justified in doing so. It will destroy democracy if it’s followed. You have to subordinate a part of yourself, a part of your views.”61

Ultimately, McNamara committed no “heresy” and remained out of loyalty to the President, but he did this at a personal and professional cost. On November 2, 1965, Norman Morrison, a Quaker anti-war activist, self-immolated outside McNamara’s office window. Morrison’s wife released a statement, which McNamara later quoted in In Retrospect that read: “He felt that all citizens must speak their convictions about our country’s actions.” Unlike Morrison, McNamara failed to do this at time when his convictions had real import. He had allowed escalation in Vietnam to go forward under false pretenses and in an economically unsustainable fashion. He had put loyalty to the President over his better judgment. On a personal level, in his memoirs he reflected on the tragedy of Morrison’s death and his reflexive tendency to “bottle[e] up [his] emotions”: “at moments like this I often turned inward instead.”62 He turned inward in many ways, both emotionally and professionally. From July onward, he fell into a pattern where he held back “in deciding how hard to push” with Johnson, putting his “feel for his relations and effectiveness with the President” above his professional obligation to present the White House with the truth.63

As the year went on, his influence on the President waned and his position became increasingly tenuous. Between July and December, continued military difficulties created additional pressures to further expand the US commitment in Vietnam. The disastrous battle of the Ia Drang Valley in November 1965, the first major engagement between US and North Vietnamese forces, created a fresh demand for more troops. Returning from another trip to Vietnam, McNamara recommended troop increases to about 400,000 in 1966 and to 600,000 in 1967. At the same time, McNamara told Johnson: “I am more and more convinced that we ought to think of some action other than military action as the only program there. I think if we do that by itself, it’s suicide. I think pushing out 300,000, 400,000 Americans out there without being able to guarantee what it will do is a terrible risk and a terrible cost.”64

As troop numbers and air sorties increased into the fall of 1965 with little success, McNamara and colleagues around him returned to the ideas of the Kennedy administration and its focus on counterinsurgency. In September 1965, Hilsman, who was now a professor at Columbia University, criticized the administration and declared that the decision to bomb North Vietnam was “tragic.” On Johnson’s instructions, McGeorge Bundy “read the riot act” to Hilsman and “arranged to have the same tune played at him hard by people he respects, beginning with Averell Harriman and Adam Yarmolinsky.”65 Yarmolinsky, who was now McNaughton’s deputy, continued to correspond with Hilsman. In November 1965, Hilsman sent him an article by Bernard Fall that was highly critical of the bombing program and its “confidence in total material superiority,” arguing that the administration was inextricably tying its credibility to a doomed and “fundamentally weak” South Vietnamese government, noting that the “bomber can’t do anything about that.”66 In June 1965, Fall had received several visits from American policy-makers, including Army Chief Johnson and Paul Kattenburg. The latter had secretly met with Fall in his home and transmitted Fall’s critical views to the Vietnam Working Group.67 At the time, Fall was largely ignored.

By contrast, in November, even while Yarmolinsky patronized Hilsman’s “academic uneasiness in an uneasy world,” he nonetheless forwarded both Hilsman’s letter and the Fall article to McNamara and John McNaughton, adding, “I think this is probably worth your reading in its entirety, and perhaps assigning for analysis.”68 Two months later, McNamara referred to this article in an exchange with McNaughton. In his diary, McNaughton noted: “He referred also to an article which said that you can’t lick guerrilla wars without a political base and you can’t lose them if you have such a base … The implication was that Thailand would resist guerrilla efforts even if SVN [South Vietnam] went down the drain. Also, the point was made that a great power can absorb political defeats, but not military ones – and that our great mistake was to let a likely political defeat get turned into a likely military defeat.”69

As military reports looked increasingly unfavorable, McNamara renewed his pressure for negotiations and for a bombing pause. In mid-November, Look magazine published an Eric Sevareid interview with US Ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson before the latter’s death in July. In it, Stevenson accused the administration of shutting the door on UN Secretary General U Thant’s mediation efforts.70 In private, Johnson dismissed Stevenson as an “amateur” and as having a “martyr complex.” Nevertheless, McNamara used the opportunity to encourage Johnson to look for political openings and to implement a longer bombing pause. He presented the President with his assessment that the chances of military success were now even or “1 in 3.” He told the President, “We may not find a military solution. We need to explore other means.”71 McNaughton’s diaries recorded a revealing exchange with U. Alexis Johnson. He wrote, “He (and State) think the future holds more than the present, and therefore had to be dragged into the present Pause. I (and DOD) think the future holds less than the present, that things are getting worse, that we have to pour more in to stand still – so strong diplomatic initiatives (and a compromise) are called for now.”72

Johnson resisted the pause, as did many of his civilian and military advisors: “Don’t we know a pause will fail?” he asked his Secretary of Defense and presented the JCS view that a pause would undo existing military progress.73 McNamara pushed back, dismissing the Chiefs’ arguments as “baloney,” and agreed with Johnson that they could use concerns over the budget and inflation to force the Chiefs to demur.74 In early December, ignoring Johnson’s pressures, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve William McChesney Martin increased interest rates, in large part because of his concerns over escalation in Vietnam and its inflationary effects.75 McNamara drew on this embarrassing development for his own purposes.

The impact of McNamara’s intervention was effective, if short-lived. When Johnson’s skeptical advisors pushed for an early resumption of bombing, McNamara interrupted his vacation to visit the President at his Texas ranch to convince him otherwise.76 McGeorge Bundy explained that the President “acquiesced” to McNamara’s request after Taylor also “[came] around” to the idea and notably after Johnson received the results of a Harris poll, whose question he had personally written, indicating support for the pause.77 Nevertheless, using his personal access to the President, McNamara overrode widespread resistance to the pause from advisors as disparate as Rusk, William Bundy, Thompson and Clark Clifford, the Chairman of the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board, who would eventually succeed McNamara. Using similar language to Johnson, Clifford felt that the administration had “talked enough about peace” and that a pause would therefore be a sign of weakness.

In an underhanded critique of their existing intelligence, McNamara also preempted the Chiefs’ anger by asking them, “If at any time you believe the pause is seriously penalizing our operations in the South, please submit to me immediately the evidence backing up your belief.”78 The pause produced a flurry of diplomatic activity. Johnson “talked directly with [Ambassador to the UN Arthur] Goldberg and Harriman,” who, if only for symbolic reasons, was appointed as “someone moving throughout the world trying for peace.”79 Whether or not McNamara played on the fact that he had recently considered leaving, he nevertheless and finally used his influence on the President to force a political opening.

On January 29, the pause ended in failure. Only two weeks earlier, McNamara had shared his view that “the Pause is paying off very well,” but Johnson and most of his advisors disagreed.80 Rusk shared Johnson’s view that the pause had been a mistake and produced no diplomatic breakthrough as McNamara had predicted: “The enormous efforts made in the last 34 days,” Rusk concluded, “have produced nothing.”81 To add to McNamara’s humiliation, Johnson reconvened the “Wise Men” who encouraged him to extend the bombing campaign to include targets McNamara had heretofore resisted: the only “worthy” targets, they suggested, were the petroleum, oil and lubricant (POL) industrial targets in the Haiphong and Hanoi areas.82

In his diaries, McNaughton noted the following exchange: “Bob mentioned that ‘for your information, the bombing resumes tomorrow noon.’ I asked what the theory is. He said ‘First, to give the right signal to the North [we have not weakened]; second, to give the right signal to the South; third to increase the cost of infiltration [more North Vietnamese devoted to repair]; fourth, to keep pressure on the North to settle; and fifth, to give us a chip for the bargaining table.’”83 He might have added a sixth, unstated objective, which was to rebuke McNamara. Johnson grew increasingly frustrated with McNamara’s “softness” on Vietnam and suspicious of his friendship with Robert Kennedy.84 McNamara had ultimately staked his personal relationship with Johnson on the bombing pause, and when it failed to produce clear successes, Johnson blamed him first.

The United States’ involvement in Vietnam changed substantially from January to December 1965. So too did McNamara as a person and as a Secretary of Defense. At the start of the year, with McGeorge Bundy, he had written to the President that “our obligations to you simply do not permit us to administer our present directives in silence and let you think we see really hope in them.”85 As the year went on, he allowed Johnson’s political calculations to distort his recommendations and learned to calibrate his views to the President’s biases. In his diary, McNaughton noted an exchange with Ray Cline, a colleague at the CIA, where “he referred to the last days of Stalin (per Khrushchev), when no one could tell his woes to anyone for fear he would be turned, and done, in. I mentioned that we even have a minor degree of the same problem in Washington!”86 McNamara was, in effect, silenced. He had become the public face of a US military commitment to Vietnam that he questioned. He provided the rationale for Operation Rolling Thunder, which he initially welcomed, and for the deployment of troops that soon followed, which he did not.

More important, with his accounting gimmicks, he had allowed the administration to sidestep an informed debate on the extension of its commitment to Vietnam. McNamara understood that the 1965 decisions marked a turning point where the nature of US involvement in Vietnam changed. He knew also that the war could not be sustained without either rallying domestic support and resources or providing a clearer end point. Neither was forthcoming and yet he stayed. The most probable reason for this was rooted in his view that no one better than he could resist the pressures to escalate further and in the threat that, as a result, China would enter the war. Above all, he stayed out of his loyalty to the presidency.

McNamara’s mistakes in Vietnam were not that he was the preeminent “hawk,” the key advisor pressuring President Johnson to escalate in Vietnam with air power and troops, but that he defined his job and loyalty in a way that was too constraining. As the official OSD history explains, “McNamara had promised an efficient and affordable defense. Vietnam ruined those goals.”87 Given this and the fact that he had been quicker than most to assess the economic costs and strategic weaknesses underpinning Johnson’s chosen policy for Vietnam, he should have spoken out for his own office as well as for the administration, if not for his country.