1.1 Introduction

This chapter sets out the knowledge commons framework that forms the foundation for the case study chapters that follow.Footnote 1 The framework is inspired by and builds in part on the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) approach pioneered by Elinor Ostrom and her collaborators for studying commons arrangements in the natural environment (Ostrom 1990). The version of the framework set out in this chapter closely tracks the version published as chap. 1 of Governing Knowledge Commons (Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg Reference Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014), and in an earlier paper (Madison, Frischmann, and Strandburg 2010a), with some important updates and revisions added to reflect lessons learned in the course of conducting the case studies published in that book. By reproducing and further refining the framework here, we hope to inspire future researchers to adopt, extend, and continue to refine it.

The systematic approach to case study design and analysis provided by the knowledge commons framework aims to structure individual case studies in a useful and productive way and to make it possible eventually to produce generalizable results. Comparing and aggregating case studies performed according to the knowledge commons framework should enable an inventory of the structural similarities and differences between commons in different industries, disciplines, and knowledge domains and shed light on the underlying contextual reasons for the differences. This structured inquiry provides a basis for developing theories to explain the emergence, form, and stability of the observed variety of knowledge commons and, eventually, for designing models to explicate and inform institutional design. In addition, an improved understanding of knowledge commons should facilitate a more complete perspective on intellectual property (IP) law and policy and its interactions with other legal and social mechanisms for governing creativity and innovation.

1.1.1 What Do We Mean by Knowledge Commons?

“Knowledge commons” is shorthand. It refers to an institutional approach (commons) to governing the management or production of a particular type of resource (knowledge).

Commons refers to a form of community management or governance. It applies to resources and involves a group or community of people, but it does not denote the resources, the community, a place, or a thing. Commons is the institutional arrangement of these elements: “The basic characteristic that distinguishes commons from noncommons is institutionalized sharing of resources among members of a community” (Madison, Frischmann, and Strandburg 2010b: 841). Critically, commons governance is used by a wide variety of communities to manage many types of resources. Commons governance confronts various obstacles to sustainable sharing and cooperation. Some of those obstacles derive from the nature of the resources and others derive from other factors, such as the nature of the community or external influences. Communities can and often do overcome obstacles through constructed as well as emergent commons. Importantly, while commons-governed institutions generally offer substantial openness regarding both informational content and community membership, they usually impose some limits relating, for example, to who contributes, what contributions are incorporated into the shared pool, who may use the pooled knowledge, or how it may be used. The limitations imposed by a knowledge commons often reflect and help resolve the obstacles to sharing encountered in its particular context.

Knowledge refers to a broad set of intellectual and cultural resources. In prior work, we used the term “cultural environment” to invoke the various cultural, intellectual, scientific, and social resources (and resource systems) that we inherit, use, experience, interact with, change, and pass on to future generations. To limit ambiguity and potential confusion, and to preserve the wide applicability of the framework, we currently use the term “knowledge.” We emphasize that we cast a wide net and that we group together information, science, knowledge, creative works, data, and so on.

Knowledge commons is thus shorthand for the institutionalized community governance of the sharing and, in many cases, creation of information, science, knowledge, data, and other types of intellectual and cultural resources. Demand for governance institutions arises from a community’s need to overcome various social dilemmas associated with producing, preserving, sharing, and using information, innovative technology, and creative works.

Some initial illustrations of knowledge commons illustrate the variety of institutional arrangements that may be usefully studied using the GKC framework. Consider the following examples from the Governing Knowledge Commons book:

Nineteenth-century journalism commons

Astronomical data commons

Early airplane invention commons

Entrepreneurial/user innovation commons

Genomic data commons

Intellectual property pools

Legispedia (a legislative commons)

Military invention commons

News reporting wire services,

Online creation communities

Open source software

Rare disease research consortia

Roller derby naming commons

Wikipedia

At first glance, these examples may appear to be disparate and unrelated. Yet we believe that a systematic, comprehensive, and theoretically informed research framework offers significant potential to produce generalizable insights into these commons phenomena. Comparative institutional investigation of knowledge commons is relevant to understanding social ordering and institutional governance generally, including via intellectual property law and policy.

1.2 Intellectual Property, Free Riding, Commons, and the GKC Framework for Empirical Study

As discussed in more detail in our earlier work, our approach to the study of knowledge commons governance is founded on three basic propositions, which we simply state here, having elaborated upon them in detail in our earlier work: First, traditional intellectual property “free rider” theory fails to account for cooperative institutions for creating and sharing knowledge that are prevalent (and perhaps increasingly so) in society. Policy based solely on this traditional view is thus likely to fail to promote socially valuable creative work that is best governed by a commons approach and may, at least in some circumstances, impede such work. Second, the widespread recognition of certain well-known successes of the commons approach, such as open source software, can itself be problematic when it ignores the significant governance challenges that often arise for such institutions. A more nuanced appreciation of the benefits and challenges of knowledge commons governance is necessary for wise policy choices. Third, the development of a more sophisticated approach to knowledge commons governance will require systematic empirical study of knowledge commons governance “in the wild.”

1.2.1 The IAD Framework for Studying Natural Resource Commons

To develop a systematic empirical approach for studying knowledge commons governance, we turned to the work of Elinor Ostrom and collaborators, who faced a similar scholarly challenge in understanding natural resource commons, such as lakes and forests. There, simplistic “tragedy of the commons” models suggested a policy space bifurcated between private property and government subsidy or top-down regulation. Real-world observation of well-functioning commons governance arrangements exposed the inadequacies of such a simplistic theoretical approach to the variety and complexity of social and natural contexts involved.

In response, Ostrom and her collaborators developed the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework for structuring and analyzing case studies of natural resource commons and situating them with respect to private property and government subsidy or regulation. A framework approach is pre-theoretical, in that it “helps to identify the elements (and the relationships among these elements) that one needs to consider for institutional analysis. Frameworks … provide the most general set of variables that should be used to analyze all types of settings relevant for the framework … They attempt to identify the universal elements that any relevant theory would need to include” (Ostrom 2005: 28–29). It thus avoids the myopia (and mistakes) that can result from forcing the complexity of real-world social behavior into a single theory or model (such as “tragedy of the commons” or “free riding”) and opens up the theoretical space so that researchers can identify salient factors and social dilemmas that should drive theoretical understanding. A framework approach also systematizes the development of general observations that can be of use both for policymaking and for understanding how to craft and apply more specific theories and models for particular cases.

The IAD framework centers on the concept of an “action arena,” in which relevant actors interact with one another to deal with the social dilemmas associated with sharing and sustaining a particular natural resource in light of its characteristics and the environment and community in which it is situated. Interactions within an action arena are governed by “rules-in-use,” which may be formal or informal, to produce particular outcomes.

Structuring a case study according to the IAD framework involves asking specific questions about the resources, actors, environment, rules-in-use, and other aspects of a particular commons arrangement that assist the researcher in drilling down into the facts of a particular case (Ostrom 2005: 13–14). The IAD framework thus allows researchers to move beyond the overly general assumptions of the “tragedy of the commons” story to investigate how resources actually are governed, structuring the empirical inquiry so that comparisons are possible, while avoiding unwarranted assumptions related to particular theories or models. Using the information obtained by applying the IAD framework to structured case studies, natural resources researchers developed theories and models for particular commons situations, designed experiments to test those theories, and used statistical methods to look for regularities across cases. Based on this empirical work, Ostrom advanced a set of design principles for successful natural resource commons (Ostrom et al. 2007: 15181–82).

1.2.2 Developing a Framework for the Study of Knowledge Commons Governance

Several years ago, Ostrom and her colleagues began to apply the IAD framework to investigate the management of collections of existing knowledge resources (Ostrom and Hess Reference Ostrom, Hess, Hess and Ostrom2007). A direct application of the IAD framework to knowledge commons had its limitations, however. In particular, it neglected (or, at least, did not emphasize) certain ways in which knowledge resources and their associated communities differ from natural resources and the communities that use and manage them. In creating the Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) framework, we identified several important distinctions and modified and extended the IAD framework to better account for the distinctive character of knowledge commons.

First, knowledge resources must be created before they can be shared. Individual motivations for participating in knowledge creation are many and various, ranging from the intrinsic to the pecuniary. Motivations may also be social and thus interwoven with the character of the community. Therefore, knowledge commons often must manage both resource production and resource use within and potentially beyond the commons community.

Second, those who participate in knowledge production necessarily borrow from and share with others – and not in any fixed or small number of ways. Indeed, it may be impossible to divest oneself of knowledge to which one has been exposed. Inevitably, the intellectual products of past and contemporary knowledge producers serve as inputs into later knowledge production. As a result, knowledge commons must cope with challenges in coordinating and combining preexisting resources to create new knowledge.

Third, because knowledge is nonrivalrous once created, there is often social value in sharing it beyond the bounds of the community that created it. The public goods character of knowledge resources necessitates consideration not only of dynamics internal to a commons community but also of relationships between those communities and outsiders. Knowledge commons must confront questions of openness that may generate additional social dilemmas (Madison, Frischmann, and Strandburg 2009: 368–69).

Fourth, intangible knowledge resources are not naturally defined by boundaries that limit their use. Depending upon the knowledge at issue and the circumstances of its creation, creators may or may not be able to limit use by others as a practical matter, for example, through secrecy. In essence, the boundaries of knowledge resources are built rather than found. Boundaries come from at least two sources. Intangible knowledge resources often are embodied in tangible forms, which may create boundaries around the embedded knowledge as a practical matter. Additionally, law and other social practices may create boundaries around knowledge resources, as, for example, in the case of the “claims” of a patent. The creation of boundaries is partly within and partly outside the control of the members of a knowledge commons community and generates a series of social dilemmas to be resolved.

Fifth, the nonrivalry of knowledge and information resources often rides on top of various rivalrous inputs (such as time or money) and may provide a foundation for various rivalrous outputs (such as money or fame). Knowledge commons must confront the social dilemmas associated with obtaining and distributing these rivalrous resources.

Sixth, knowledge commons frequently must define and manage not only these resources but also the make-up of the community itself. Knowledge commons members often come together for the very purpose of creating particular kinds of knowledge resources. The relevant community thus is determined not by geographical proximity to an existing resource, but by some connection – perhaps of interest or of expertise – to the knowledge resources to be created. Moreover, the characteristics of the knowledge created by a given community ordinarily are determined, at least to some extent, by the community itself. Thus, neatly separating the attributes of the managed resources from the attributes and rules-in-use of the community that produces and uses them is impossible.

Finally, because of the way in which knowledge resources and communities are co-created, both tend to evolve over time. Thus, to understand knowledge commons governance, it is often crucial to engage with the particular narratives of the community, which may be grounded in storytelling, metaphor, history, and analogy. The property scholar Carol Rose emphasizes the role of narratives, especially of origin stories, in explaining features of property regimes that are not determinable strictly on theoretical or functional grounds, particularly if one assumes that everyone begins from a position of rational self-interest (Rose 1994: 35–42). The stories that are told about knowledge commons, and by those who participate in them, are instructive with respect to understanding the construction, consumption, and coordination of knowledge resources. Particular histories, stories, and self-understandings may be important in constructing the social dilemmas that arise and in determining why a particular knowledge commons approaches them in a particular way.

The GKC framework for conducting case-based research and collecting and comparing cases is intended to be inclusive, in that various disciplinary perspectives, including law, economics, sociology, and history, may be relevant to applying it to particular cases. By design, and in light of our still-nascent understanding of knowledge commons governance, the GKC framework remains a work in progress, which will be most valuable if it is developed and honed as more examples are studied. Indeed, the description here already reflects some reorganization and fine-tuning of our initial take on the framework as presented in earlier work (Madison, Frischmann, and Strandburg 2010a).

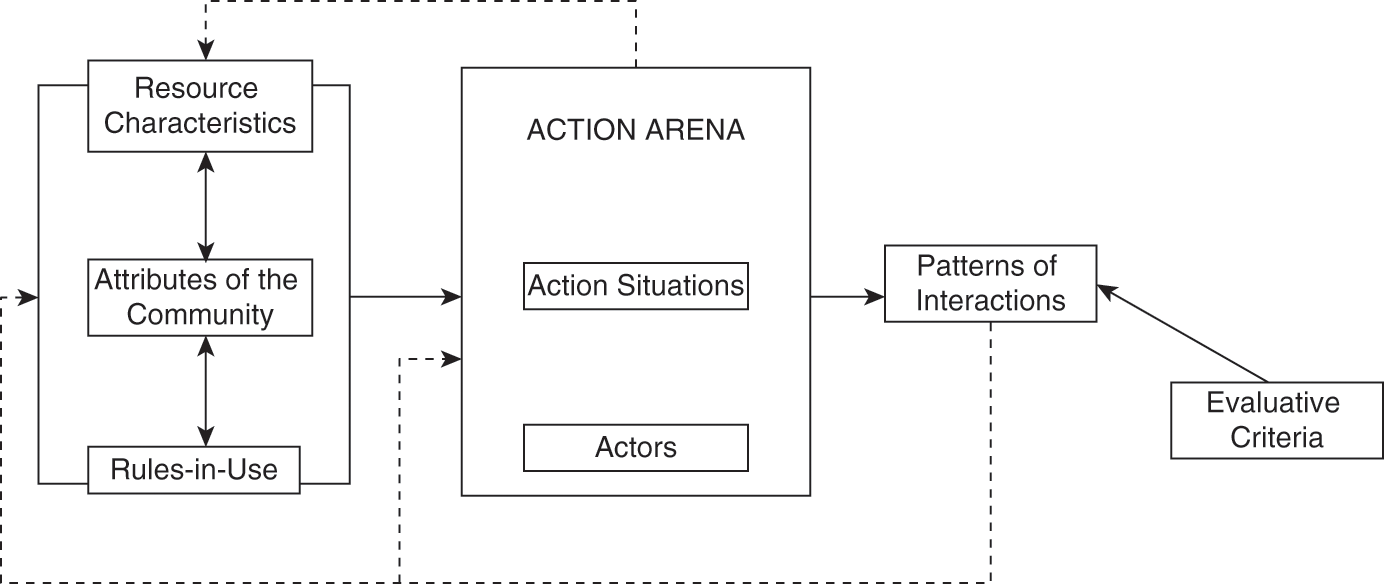

We illustrate the GKC framework and its relationship to the IAD framework with the flow charts in Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

Figure 1.1 Based on a flow chart used to illustrate the IAD framework (Ostrom 2005: 15). It pictures the way in which relevant variables, including the biophysical characteristics of the natural resource, the attributes of the community, and the rules-in-use in the community influence the way in which actors interact in particular action situations to produce patterns of interactions and outcomes, which may be evaluated from a social perspective through evaluative criteria. The dotted lines illustrate the way in which the outcomes from a given pattern of interactions can influence the input variables, for example, by leading to destruction or sustainability of the resource or to modifications of the rules-in-use because the community is dissatisfied with the outcomes.

Figure 1.2 The GKC framework. Because of the more complex relationships among resources, participants, and governance structures in knowledge commons, relevant attributes may not divide as neatly into categories as they do when one is describing a pool of natural resources. Thus, in the leftmost part of the chart, we connect the resources characteristics, community attributes, and rule-in-use to emphasize their interrelated and contingent character. The dotted line leading directly from the action arena to resource characteristics illustrates the way in which interactions in the action arena, by creating intellectual resources, feed directly back into resource characteristics without being mediated by ongoing patterns of interactions.

Figure 1.2 also collapses a distinction made in the original IAD framework between “patterns of interactions” that follow from the action arena and outcomes that follow from the patterns of interaction. The patterns of interactions generated by the formal and informal rules systems of a knowledge commons are often inseparable from the outcomes it produces. How people interact with rules, resources, and one another, in other words, is itself an outcome that is inextricably linked with and determinative of the form and content of the knowledge or informational output of the commons. In an open source software project, for example, the existence and operation of the open source development collaborative, the identity of the dynamic thing called the open source software program and the existence and operation of the relevant open source software license and other governance mechanisms are constitutive of one another.

With this general picture in mind, we now lay out the GKC framework for empirical study of knowledge commons in the box, “Knowledge Commons Framework and Representative Research Questions.” More detail about the various aspects of the framework is provided in our earlier work and illustrated in the case studies in this book.

During the course of a case study, the framework of questions summarized in the box is used in two ways. First, it is used as a guide in planning interviews with relevant actors, documentary research, and so forth. Second, it is used as a framework for organizing and analyzing the information gained from interviews, relevant documents, and so forth. Though we list the various “buckets” of questions in the framework sequentially, in practice the inquiry is likely to be iterative. Learning more about goals and objectives is likely to result in the identification of additional shared resources; understanding the makeup of the community will lead to new questions about general governance, and so forth.

Knowledge Commons Framework and Representative Research Questions

Background Environment

What is the background context (legal, cultural, etc.) of this particular commons?

What is the “default” status, in that background context, of the sorts of resources involved in the commons (patented, copyrighted, open, or other)?

Attributes

Resources

What resources are pooled and how are they created or obtained?

What are the characteristics of the resources? Are they rival or nonrival, tangible or intangible? Is there shared infrastructure?

What technologies and skills are needed to create, obtain, maintain, and use the resources?

Community Members

Who are the community members and what are their roles?

What are the degree and nature of openness with respect to each type of community member and the general public?

Goals and Objectives

What are the goals and objectives of the commons and its members, including obstacles or dilemmas to be overcome?

What are the history and narrative of the commons?

Governance

What are the relevant action arenas and how do they relate to the goals and objective of the commons and the relationships among various types of participants and with the general public?

What are the governance mechanisms (e.g., membership rules, resource contribution or extraction standards and requirements, conflict resolution mechanisms, sanctions for rule violation)?

Who are the decision makers and how are they selected?

What are the institutions and technological infrastructures that structure and govern decision making?

What informal norms govern the commons?

How do nonmembers interact with the commons? What institutions govern those interactions?

What legal structures (e.g., intellectual property, subsidies, contract, licensing, tax, antitrust) apply?

Patterns and Outcomes

What benefits are delivered to members and to others (e.g., innovations and creative output, production, sharing, and dissemination to a broader audience, and social interactions that emerge from the commons)?

What costs and risks are associated with the commons, including any negative externalities?