16 results

1 - The Imperial State

- from I - 1750–1819: The Ends of the Ancien Régime

-

- Book:

- Modern Britain, 1750 to the Present

- Published online:

- 14 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 January 2025, pp 3-39

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 17 - Liberating Third World Theatre

-

-

- Book:

- A New History of Theatre in France

- Published online:

- 22 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 329-346

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Anti-Fleming Sentiment and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381

-

- Book:

- Flemish Textile Workers in England, 1331–1400

- Published online:

- 16 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 240-265

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Violence and the French Revolution

- from Part I - France

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Age of Atlantic Revolutions

- Published online:

- 18 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 195-224

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Sultans of the Open Lands (1858–1890)

-

- Book:

- Locusts of Power

- Published online:

- 16 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 25 May 2023, pp 24-83

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

12 - Genocidal Perspectives in the Roman Empire’s Approach towards the Jews

- from Part II - The Ancient World

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge World History of Genocide

- Published online:

- 23 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 04 May 2023, pp 330-352

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Entangled Empires

-

- Book:

- The Great Plague Scare of 1720

- Published online:

- 11 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 01 December 2022, pp 177-213

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Rebellion at the Workhouse

-

- Book:

- All for Liberty

- Published online:

- 09 December 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 December 2021, pp 116-144

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

All for Liberty

- The Charleston Workhouse Slave Rebellion of 1849

-

- Published online:

- 09 December 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 December 2021

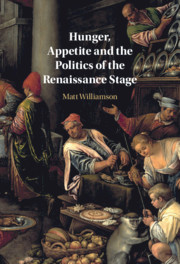

Hunger, Appetite and the Politics of the Renaissance Stage

-

- Published online:

- 28 May 2021

- Print publication:

- 10 June 2021

Chapter 4 - Camus’s Modernist Forms and the Ethics of Tragedy

-

- Book:

- Tragedy and the Modernist Novel

- Published online:

- 20 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 10 September 2020, pp 108-149

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Chains of Solidarity

- from Part I - Transnational Solidarity

-

-

- Book:

- Transnational Solidarity

- Published online:

- 04 July 2020

- Print publication:

- 09 July 2020, pp 61-75

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Towards Partition

- from Part II - Colonial Encounters

-

- Book:

- A History of Bangladesh

- Published online:

- 17 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 July 2020, pp 104-111

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Colonial Conflicts

- from Part II - Colonial Encounters

-

- Book:

- A History of Bangladesh

- Published online:

- 17 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 July 2020, pp 93-103

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

London's Hadrianic War?

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Immigration and the Common Profit: Native Cloth Workers, Flemish Exiles, and Royal Policy in Fourteenth-Century London

-

- Journal:

- Journal of British Studies / Volume 55 / Issue 4 / October 2016

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 October 2016, pp. 633-657

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation