Food security occurs ‘when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’( 1 ). Food insecurity (FI) exists when these conditions are not met and is a major underlying cause of undernutrition enshrined in the UNICEF conceptual framework( 1 , 2 ).

FI is a major risk factor for adverse health outcomes among specific vulnerable populations including persons infected with HIV( Reference Weiser, Young and Cohen 3 , Reference Ivers, Cullen and Freedberg 4 ), women( Reference Whitaker, Phillips and Orzol 5 ) and children( Reference Whitaker, Phillips and Orzol 5 , Reference Cook, Frank and Berkowitz 6 ). Women’s responsibilities in managing family feeding( Reference Olson 7 ), gender bias in the experience of FI( Reference Hadley, Lindstrom and Tessema 8 ) and unequal control over household resources make them particularly vulnerable to FI and its consequences( Reference Weiser, Young and Cohen 3 ). Data from the USA indicate that, when faced with FI, women suffer a range of negative nutritional( Reference Laraia, Siega-Riz and Gundersen 9 ) and psychosocial consequences( Reference Laraia, Siega-Riz and Gundersen 10 , Reference Hromi-Fiedler, Bermúdez-Millán and Segura-Pérez 11 ).

Pregnant women are more likely to experience greater FI than non-pregnant women because they have higher nutrient demands, less physical ability to obtain and prepare food (especially later in pregnancy and early postpartum) and less ability to engage in income-generating labour( Reference Laraia, Siega-Riz and Gundersen 10 ). The three studies to date about FI among pregnant women have shown that FI has serious negative nutritional and psychosocial impacts on women’s health( Reference Laraia, Siega-Riz and Gundersen 9 – Reference Hromi-Fiedler, Bermúdez-Millán and Segura-Pérez 11 ). However, all of these studies were done in the USA and contextual differences between resource-rich and resource-poor settings make the generalizability of these findings questionable. For instance, a higher burden of infectious diseases and poverty in resource-poor settings may exacerbate women’s experiences of FI. Thus, it is important to document the burden and impacts of FI among pregnant women living in resource-poor settings.

The first step to understanding the consequences of FI is to be able to appropriately measure the FI construct. Measures of food security tend to focus on three important and hierarchical domains: availability, access and utilization of food( 12 ). Whereas measures of food availability (e.g. food stocks at national, community and household levels) and utilization (e.g. through assessment of nutritional status) are much easier to ascertain, measuring food access has been more difficult.

There is an increasing focus on assessing the access domain of FI given the emerging psychosocial impacts of FI. Approaches to measuring food access have included both indirect and direct methods( Reference Jones, Ngure and Pelto 13 ). Indirect methods of measuring food access tend to focus on proxy measures such as household income and expenditures, dietary diversity or other livelihood strategies. In contrast, direct, experience-based measures tend to rely on individuals’ and families’ behaviours and past experiences of FI using questionnaires( Reference Jones, Ngure and Pelto 13 ). The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS)( Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky 14 ) is perhaps the most frequently used experience-based measure of food access. The HFIAS consists of nine questions, each of which has four response options (no=0, rarely=1, sometimes=2, often=3). An overall HFIAS score can therefore be derived, with total scores ranging from 0 to 27, with higher scores reflecting more severe FI.

Existing scales for assessing food access, such as the HFIAS, focus on household FI. However, intra-household differences in the experience of FI( Reference Hadley, Lindstrom and Tessema 8 , Reference Abdullah and Wheeler 15 ) suggest that food access should also be assessed at the individual level. For this reason, we explored the reliability and validity of a modified HFIAS questionnaire, in which we focused on respondents’ individual experiences, rather than asking about those of the entire household. The resultant scale is an individually focused FI access scale, or the IFIAS.

It is recommended that measures of FI be validated through qualitative( Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky 14 , Reference Alaimo, Olson and Frongillo 16 ) and quantitative approaches( Reference Frongillo 17 , Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Segall-Corrêa and Kurdian Maranha 18 ) so as to ensure their appropriateness. Although the HFIAS has been used and validated to assess FI in a number of countries( Reference Jones, Ngure and Pelto 13 ), we did not find any study that had adapted and/or validated this scale to assess individual-level FI. Therefore, to ensure that FI access measures obtained using the IFIAS are reliable, valid and reflect specific contextual factors, we collected qualitative and quantitative data from pregnant women participating in the Prenatal Nutrition and Psychosocial Health Outcomes (PreNAPs) study.

Materials and methods

Data were collected in the context of the PreNAPs study, a longitudinal observational study designed to document the relationships between food access, nutritional and psychosocial exposures and a number of physical and mental health outcomes among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women in post-conflict northern Uganda. Data were collected between 10 October 2012 and 29 August 2013 at the antenatal care clinic of Gulu Regional Referral Hospital (GRRH) in Gulu, northern Uganda. The antenatal care clinic of GRRH is a busy primary care clinic, attending to approximately 400 newly pregnant women on a monthly basis. All services at GRRH, including medications, are offered free of charge, as they are in other public hospitals and clinics in Uganda.

Population

Women were invited to participate in the PreNAPs study if they were between 10 and 26 weeks’ gestation, lived within 30 km of GRRH and had a known HIV status. Women whose HIV status was unknown were excluded. HIV-infected women were oversampled to achieve a ratio of one HIV-infected to two HIV-uninfected participants; and thus the proportion of HIV-infected women in our sample is much higher than the 10·3 % age-adjusted prevalence of HIV observed at various antenatal care clinics in northern Uganda( Reference Fabiani, Nattabi and Pierotti 19 ).

Study design

We used a mixed-methods approach to validate the IFIAS. Prior to administration, questionnaires were adapted for use with our specific study population (e.g. by changing the HFIAS into the IFIAS) and translated into Acholi and Langi, the two dominant Luo languages in the area, and then back-translated into English by three Acholi/Langi-speaking key informants. These included a medical psychiatrist working for GRRH, a study nutritionist and a midwife. Discrepancies in conceptual and semantic equivalence were resolved through discussions. The research team discussed all translated versions and adaptation of the questionnaires until final versions of the questionnaires were agreed upon.

Qualitative validation of the IFIAS

We conducted qualitative cognitive interviews with a subset of cohort participants to ensure the appropriateness of the IFIAS questions (n 26). As in the main study sample, about one-third (34·6 %) of the cognitive interview participants were HIV-infected. Cognitive interviewing is a methodology used to evaluate sources of error/improve quality of survey instruments( Reference Willis 20 ) that has been used successfully to understand respondents’ experiences with the Radimer/Cornell FI questions( Reference Alaimo, Olson and Frongillo 16 ). Cognitive interviews were oriented around the nine IFIAS questions. Specifically, we used cognitive testing methods to assess:

-

1. Comprehension of questions, i.e. to determine whether respondents perceived the intent of IFIAS questions as intended.

-

2. Retrieval from memory information relevant to the questions, i.e. to determine whether respondents were able to repeat questions we had asked them and the thought processes they went through to come up with a response to the question.

-

3. Response process, i.e. to assess whether the response options are appropriate and/or adequate.

Cognitive interviews were conducted by an Acholi-speaking study nutritionist (H.K.).

Quantitative validation of the IFIAS

We also validated the IFIAS quantitatively among the entire study cohort (n 403). Because there is no ‘gold standard’ for measuring FI access, we employed approaches that involve establishing construct rather than criterion validity of the IFIAS (Table 1). Construct validity is defined as the extent to which a given measurement corresponds to theoretical concepts (constructs) concerning the phenomena under study, while criterion validity is the extent to which measurements obtained using a new scale concur with those determined with an established diagnostic test or gold standard( Reference Porta 21 ). Construct validity is further divided into convergent and discriminant validity( Reference Strauss and Smith 22 ). Whereas convergent validity looks at establishing whether a given test measure or outcome is not correlated with concepts or constructs one would expect it to be related with, the goal of discriminant validity is to demonstrate that a given test measure or outcome is not correlated with concepts or constructs that are generally considered to be unrelated to it. Discriminant validity has been erroneously referred to as divergent validity( Reference Strauss and Smith 22 ). In the current study, we assessed the convergent validity of the IFIAS using a number of measurements (Table 1).

Table 1 Definitions of terms conceptually important for testing the reliability and validity of measurement scales

IFIAS, individual-level food insecurity access scale.

Survey data collection

At enrolment into the cohort study, trained interviewers administered a questionnaire lasting approximately 45min. Individual-level FI was assessed using the IFIAS. Sociodemographic data collected included maternal characteristics such as age, education, residence, and previous experience with displacement or residence in a camp for internally displaced people (IDP). Wealth was based on the possession of twenty different household assets obtained using the socio-economic module of the 2009–10 Uganda National Panel Survey( 23 ). Health information including gestational age (based on first day of the last menstrual period) and maternal HIV status (determined at the antenatal care clinic prior to enrolment into the PreNAPs study) were also documented. Diet quality was assessed using the women’s dietary diversity score (WDDS)( Reference Kennedy, Ballard and Dop 24 ). The WDDS is based on the sum of nine food groups consumed in the 24 h preceding the food recall interview. The following set of food groups are recommended for calculating the WDDS: (i) starchy staples; (ii) dark green leafy vegetables; (iii) other vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; (iv) other fruits and vegetables; (v) organ meats, meat and fish; (vi) eggs; (vii) legumes; (viii) nuts and seeds; and (ix) milk and milk products.

Data analysis

Cognitive interviews were transcribed in Acholi and translated into English immediately after each interview. We then looked for common themes and discrepancies in respondents’ answers to each question. Understanding of the meanings of items and/or important phrases in each item was then summarized or tallied, as appropriate.

Survey data were entered into EPIDATA 3·1 and analyses were conducted using the statistical software package STATA 12. The IFIAS score and FI categories were based on pregnant women’s responses to the nine-item scale, as recommended by Coates et al. for the HFIAS( Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky 14 ). Frequency distributions of responses to all nine IFIAS items were also performed. We derived a wealth index proxy variable, asset index, using the principal component analysis methodology. Per this methodology, households with higher values on the principal component analysis-generated asset index represent greater household wealth relative to others in the sample( Reference Filmer and Pritchett 25 ).

The reliability of the IFIAS was assessed using both exploratory factor analysis and Cronbach’s test for internal consistency (Table 1). For factor analysis, we used varimax-rotated exploratory factor analysis, retaining factors with eigenvalues above 0·5. We developed subscales using items that consistently grouped together and had factor loadings with values greater than 0·45. The internal consistency of the entire nine-item IFIAS and emergent subscales was assessed using Cronbach’s α. Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0·7 or greater were considered to be reliable( Reference Santos 26 ).

As recommended by Frongillo( Reference Frongillo 17 ), we tested the parallelism of IFIAS item responses by plotting the proportion of affirmative responses within categories (tertiles) of household asset index. Additionally, we documented the dose–response association between the IFIAS score and indicator variables for socio-economic status and diet quality by assessing how the mean asset index and WDDS varied across quartiles of IFIAS scores.

We determined the convergent validity of the IFIAS using Pearson’s correlation coefficients (for exploring how IFIAS was correlated with continuous variables) and t tests (for differences in IFIAS by dichotomous variables). We used non-parametric tests for assessing trends (for categorical variables with more than two categories and assuming ordinal groupings) to compare the performance of the IFIAS scores within categorical measures of education, wealth and diet quality.

Multivariate linear regression was used to examine the independent effects of individual, demographic and socio-economic characteristics on IFIAS scores. We included variables with P values ≤0·20 in bivariate analyses into the multivariate model, but only retained variables with P values ≤0·05 in the final model.

Results

Participant characteristics

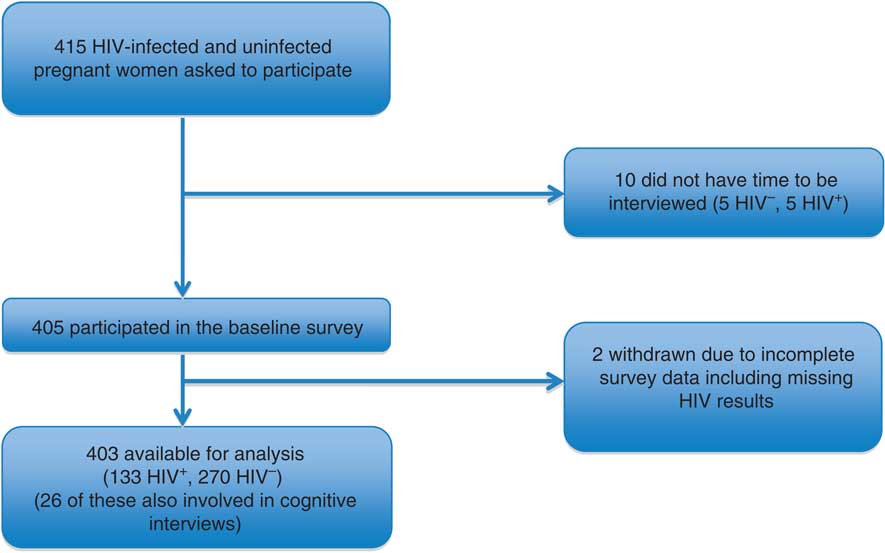

Of the 415 participants asked to participate in the PreNAPs study, 405 were enrolled (Fig. 1). The ten women who refused enrolment declined, citing ‘no time’. Of the 405, two participants did not complete the entire interview, requesting to come later but never returned, and were excluded from the analysis. Of the 403 remaining participants, 33·0 % (n 133) were HIV-infected.

Fig. 1 Diagram of participant flow in the present study

Participants selected for the cognitive interview study were similar, but not identical, to the sample in the parent study (Table 2). They were primarily Acholi-speaking Christians, with a mean age of about 25 years and lived with approximately four other people. A greater proportion of cognitive interview participants had less education.

Table 2 Characteristics of pregnant participants in the validation study of the individual-level food insecurity access scale (IFIAS), northern Uganda, October 2012–August 2013

IDP, internally displaced people; IQR, interquartile range; WDDS, women’s dietary diversity score.

Data are presented as percentage for categorical variables; or as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range for continuous variables.

* See Filmer and Pritchett( Reference Filmer and Pritchett 25 ) for details on derivation of the asset index.

† Categories constructed based on Coates et al.( Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky 14 ).

‡ See Kennedy et al.( Reference Kennedy, Ballard and Dop 24 ) for derivation of the WDDS.

The mean IFIAS score was 9·5 (sd 5·7) for participants in the overall study and 9·3 (sd 5·2) for women participating in the cognitive interviews. Based on the categorization procedure suggested by the authors of the HFIAS( Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky 14 ), 74·5 % of respondents in the main survey perceived themselves to be moderately or severely food insecure.

Cognitive interview results

As one of the first cognitive interview activities, participants were asked to paraphrase the main message of each of the IFIAS items (Table 3). In general, their responses indicated that the items were understood as we had intended. For example, for item 1, we asked respondents what they thought ‘enough food’ meant. Responses were translated to mean phrases like ‘food that is enough for me, my family members, children and visitors’ (n 8) and ‘food that satisfies me’ (n 6).

Table 3 Participants’ interpretations and understanding of the questionnaire items on the individual-level food insecurity access scale (IFIAS) in cognitive interviews (n 26) among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women attending antenatal care services in northern Uganda, October 2012–August 2013

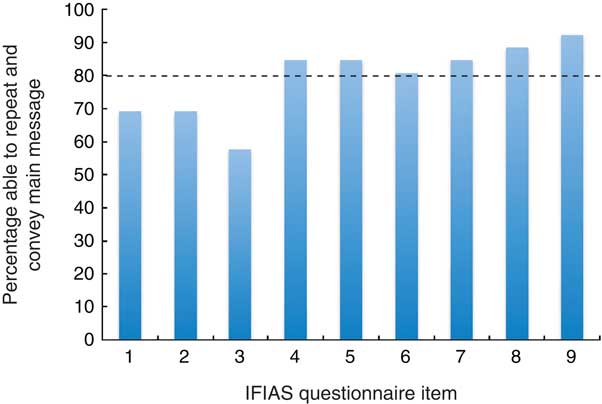

A majority of the respondents (>80 %) in the cognitive interview study were able to appropriately repeat and convey the primary meaning of IFIAS items 4 to 9 (Fig. 2). For IFIAS items 1 and 2, the proportion of participants in the cognitive interview study who were able to convey their meaning dropped to slightly below 70 %. The most difficult to understand IFIAS item was item 3 (concerning if a respondent had to eat a limited variety of foods due to a lack of resources), with 58 % of cognitive interview participants able to repeat it and provide adequate information with regard to what the item meant.

Fig. 2 Proportion of respondents who were able to repeat and convey the main message of each question item of the individual-level food insecurity access scale (IFIAS) among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women (n 26) attending antenatal care clinics in northern Uganda, October 2012–August 2013. --- indicates 80% mark at which cognitive interview participants were able to appropriately repeat and convey the correct meaning of IFIAS items 4–9

IFIAS survey results

Overall, affirmative responses (rarely+sometimes+often) on each of the nine IFIAS items ranged from 16·0 to 87·9 % (Table 4). As expected, responses to IFIAS items indicating less severe FI such as item 2 (not able to eat the kind of foods you preferred) were more prevalent than items indicating more severe FI such as item 9 (going a whole day and night without eating food). Item 2 received the most affirmative responses while item 9 received the least.

Table 4 Distribution of affirmative responses to items on the individual-level food insecurity access scale (IFIAS) and varimax-rotated factor loadings of the items among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women (n 403) attending antenatal care services in northern Uganda, October 2012–August 2013

Reliability and construct validity

Two factors emerged from rotated exploratory factor analysis of the IFIAS items. We labelled these as ‘mild to moderate FI access’ (factor 1) and ‘severe FI access’ (factor 2). Items 1–6 loaded on to the mild to moderate FI access factor with factor loadings ranging from 0·49 to 0·76, while items 7–9 loaded on to the severe FI factor with factor loadings ranging from 0·58 to 0·76. Of all items, item 4 loaded most poorly on to the mild to moderate FI factor with a loading of 0·49, while item 9 was the poorest to load on the severe FI factor with a loading of 0·58. The mild to moderate FI factor (items 1–6) explained 75·4 % of the total variance while the severe insecurity factor explained 15·0 % of the variance. The nine-item IFIAS and the two subscales had moderate to high internal consistency. Cronbach’s α for the full IFIAS scale was 0·87, 0·86 for the subscale consisting of items 1–6 and 0·75 for the subscale consisting of items 7–9.

Parallelism across tertiles of household asset index

Figure 3 shows the proportion of affirmative responses to each of the nine IFIAS items across tertiles of household asset index. Women in the lowest and middle asset tertiles showed little difference in response to IFIAS items 1–5, but the proportion of affirmative responses on these items for women in the highest asset tertile was markedly lower. For IFIAS items 6–9, we observed clear parallelism of IFIAS item response curves across the asset index tertiles. Affirmative responses to each of the nine IFIAS items, especially items 6–9, showed clear parallelism across tertiles of women’s household asset index.

Fig. 3 Item response curves showing proportion of respondents who answered affirmatively to each question item of the individual-level food insecurity access scale (IFIAS) across tertiles of household asset index among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women (n 403) attending antenatal care clinics in northern Uganda, October 2012–August 2013

Dose–response associations

We observed dose–response associations between severity of FI (represented by the quartile of FI score) and mean (i) household asset index and (ii) WDDS (Fig. 4). Mean asset index and WDDS of the fourth quartile of FI scores was the lowest compared with the first quartile of FI. Unlike the performance of the IFIAS on the parallelism requirement, the overall score on the IFIAS showed a clear-cut dose–response association with respect to WDDS and asset index variables.

Fig. 4 Dose–response association between mean asset index, women’s diet diversity score (WDDS) and quartile of food insecurity access measured by the individual-level food insecurity access scale (IFIAS) among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women (n 403) attending antenatal care clinics in northern Uganda, October 2012–August 2013

Factors associated with food insecurity

In bivariate analyses, FI status was significantly and positively associated with maternal age, number of children below 18 years, maternal HIV infection and marital status (i.e. being separated, divorced or widowed; Table 5). Conversely, we observed negative associations between FI and the asset index, formal employment status and WDDS.

Table 5 Bivariate associations between demographic and socio-economic characteristics and score on the individual-level food insecurity access scale (IFIAS) among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women (n 403) attending antenatal care services in northern Uganda, October 2012–August 2013

IDP, internally displaced people; WDDS, women’s dietary diversity score.

* Children defined as <18 years.

† See Filmer and Pritchett( Reference Filmer and Pritchett 25 ) for details on derivation of the asset index.

‡ See Kennedy et al.( Reference Kennedy, Ballard and Dop 24 ) for derivation of the WDDS.

Contextual factors important for the northern Uganda study setting such as previous history of displacement or stay in an IDP camp were also adversely associated with FI.

In a multivariate linear regression analysis, FI was associated with maternal age, number of children below 18 years, asset index, HIV status, formal employment status, diet diversity and previous stay in an IDP camp (Table 6). These analyses further confirm the conceptual and contextual relevance of the IFIAS, given that the IFIAS scores were associated with factors expected to be related to them a priori.

Table 6 Final multivariate model of covariates of individual-level food insecurity among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women (n 403) attending antenatal care services in northern Uganda, October 2012–August 2013

IDP, internally displaced people; WDDS, women’s dietary diversity score.

Discussion

In this first mixed-methods validation study of an individually focused FI access scale among pregnant women of mixed HIV status, our data indicate that the IFIAS is an appropriate measure of individual-level FI access. Specifically, most pregnant women understood each of the nine items in the IFIAS (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Further, the output of the IFIAS provided moderate to high reliability (Table 4), strong construct validity (Tables 4–6 and Figs 3 and 4) and fidelity towards conceptual and contextual factors (Tables 5 and 6) associated with FI in the northern Uganda setting. The HFIAS, the original scale from which the IFIAS scale is derived, was designed to be relevant across different contexts and cultures and our results with the IFIAS further affirm that it can be used in a number of settings.

During quantitative validation of the IFIAS, rotated exploratory factor analysis produced two main factors: the mild to moderate FI factor and the severe FI factor. These groupings differed from the three groupings the creators of the HFIAS had proposed( Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky 14 ). Instead of item 1, items 2–4 and items 5–9 on the IFIAS emerging as three different factors as intended with the HFIAS, we observed two new groupings: items 1–6 and items 7–9. This is similar to findings from previous authors’ work with item 1 of the HFIAS( Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser 27 ) or of the Radimer/Cornell scale( Reference Leyna, Mmbaga and Mnyika 28 ), whose wording in both scales is similar. There, neither term emerged as a stand-alone factor in the exploratory factor analyses. However, the inclusion of IFIAS items 5 and 6 together with items 2–4 in the same grouping is novel to our study. Reports by Mohammadi et al.( Reference Mohammadi, Omidvar and Houshiar Rad 29 ) using data from Iran and by Kneuppel et al.( Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser 27 ) using data from rural Tanzania indicated that item 5 grouped together with HFIAS items 1–4 while item 6 grouped with items 7–9. In the study by Kneuppel et al., the factor loading for item 6 in each of their two emergent factors was above their selected cut-off of 0·5, indicating that potentially HFIAS item 6 can group with HFIAS items 1–5, as was observed in our study.

The loadings that we observed on items 7–9, however, are similar to those described by Deitchler et al. in their analysis of seven data sets involving the HFIAS from six different countries( Reference Deitchler, Ballard and Swindale 30 ). Based on their findings, the authors recommended a three-item scale including items 7, 8 and 9 of the HFIAS, and called it the Household Hunger Scale. The relatively high factor loadings for items 7, 8 and 9 into a separate subscale that we observed provides further support for the cross-cultural validity of the Household Hunger Scale.

The reliability coefficients of the full IFIAS and one of the two emergent subscales observed were above the 0·85 cut-off recommended by Frongillo( Reference Frongillo 17 ) and thus suggested high internal consistency of FI scales (Table 4). Whereas the reliability coefficient of the subscale with items 7–9 was lower than the recommended cut-off, the observed value of 0·75 is also higher than 0·70, which is a generally accepted cut-off value for internal consistency of measurement scales( Reference Santos 26 ). The reliability of the full IFIAS and its subscales was in the same range as what has been reported by previous authors validating FI scales in other sub-Saharan settings( Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser 27 , Reference Leyna, Mmbaga and Mnyika 28 ). Kneuppel et al. validated the HFIAS in rural Tanzania and reported Cronbach’s α values ranging from 0·83 to 0·90, while Leyna et al. also working in Tanzania with the Radimer/Cornell scale reported values ranging from 0·78 to 0·89.

The proportion of affirmative responses on each of the nine items on the IFIAS generally followed expected patterns, with greater proportions of participants reporting affirmative responses to items indicating moderate (rather than severe) FI (Table 4). The observed trends in affirmative responses, previously reported elsewhere( Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser 27 ), were along an FI severity continuum. However, unlike the initial HFIAS report( Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky 14 ), but consistent with observations from previous studies with the HFIAS( Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser 27 ), we did not find the greatest number of affirmative responses to IFIAS item 1 (Table 4 and Fig. 3). Indeed, IFIAS item response patterns indicate that item 2 had the highest proportion of affirmative responses, followed by item 4. These results may relate to the possibility that individual and household FI are related but differ. Additionally, this may imply that worrying about food may be perceived differently in different contexts, and/or that actually worrying about food is unlikely to be as prevalent as, for example, consuming a less diverse diet – a common occurrence in resource-poor settings. It has been reported, for example, that relatively more Bangladeshi households affirmed consuming lower-quality food than worried about their food supply( Reference Coates, Frongillo and Rogers 31 ).

In the absence of a clear-cut ‘gold standard’ measure of individual-level FI, we relied on establishing other aspects of validity of the IFIAS. We evaluated how measures of FI obtained by the IFIAS stood together as a unified construct or broke into domains or subscales as originally intended by the developers of the HFIAS. We found that the IFIAS broke into two domains (Table 4), rather than the three primary HFIAS domains of being anxious and uncertain about food, relying on a diet of insufficient quality and subsisting on reduced food quantities. However, results from exploratory factor analysis indicated that two domains or subscales emerged with the IFIAS items 1–6 in one domain and items 7–9 in a separate domain. Since this grouping is still consistent with the items’ relative importance in establishing FI severity, we believe this outcome is an indication of appropriate construct validity.

It is recommended that measures obtained by FI scales demonstrate parallelism on item response curves and dose–response relationships with respect to economic and diet quality indices( Reference Frongillo 17 , Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Segall-Corrêa and Kurdian Maranha 18 ). As Fig. 3 shows, a greater proportion of persons in the lowest tertile of asset index gave affirmative responses to each of the nine IFIAS items compared with those in the highest tertile of asset index. From item 1 through item 5, differences between the proportions of responses on each IFIAS item between participants within the different asset index tertiles are less dramatic than for items 6–9. As one progresses from item 6 to item 9, clear parallel trends emerge in the proportion of affirmative responses across the tertiles. We did not detect much difference in the perceptions of anxiety and uncertainty about food or limited diet quality, as reflected in IFIAS items 1 through 5, between the poorest and middle tertiles. As one transitions from IFIAS item 6 to item 9, one sees more severe forms of FI including actual reductions in food stocks and greater hunger.

Similar to the observation of parallelism across questionnaire item response curves noted above, we observed dose–response associations between FI measures and mean asset index and WDDS (Fig. 4). This further suggests strong convergent validity with our individually focused FI scale.

Construct validity was further established by assessing the convergence of measures of FI with other demographic, socio-economic and contextual factors expected to be associated with FI. Indeed, bivariate and multivariate analyses indicated that higher FI scores were positively associated with being older, having many children below 18 years, being HIV-infected and having a history of previous stay in an IDP camp (Tables 5 and 6). On the other hand, and as expected, IFIAS measures were negatively associated with higher asset index, being formally employed and WDDS. Others have documented the relationship between FI and respondents’ increased age and greater number of children( Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser 27 , Reference Nagata, Magerenge and Young 32 ) and household socio-economic indicators( Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser 27 ) such as household wealth status and the education level of either spouse.

Most of the factors associated with FI in our study are well known to be related to FI( Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser 27 , Reference Nagata, Magerenge and Young 32 ). We were, however, surprised to find that having ever resided in an IDP camp is significantly associated with FI even several years after the civil war in northern Uganda ended. The IDP camps were closed during the period 2007–2012 with former IDP camp residents often returning to homes and farms that had been neglected for years. Factors contributing to greater perceived individual FI access among former IDP residents need to be investigated so that appropriate interventions can be targeted and implemented.

The strengths of the present study include the use of multiple measures of reliability and validity; comparison of scale performance across a multiplicity of conceptually driven and contextual determinants of FI; and use of a number of statistical tests to assess the utility of the IFIAS as a measure of individual-level FI among HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women in northern Uganda.

There are also several limitations. In order to conserve resources, we conducted the cognitive interviews concurrently with the main survey; ideally cognitive interviews would have preceded the survey. Thus, we were unable to test modifications of the IFIAS items based on cognitive interview results. The finding from cognitive interviews that IFIAS item 3 was the most difficult to understand is novel to our study, and it might have impacted negatively on our findings. The cross-sectional study design precluded assessment of the stability of FI measures over time. This limitation will be addressed by repeated measures of FI in the PreNAPs cohort. Finally, while our study is designed to have strong internal validity, our cohort does not represent the general pregnant women’s population in Gulu or northern Uganda due to the oversampling of HIV-infected women. Our oversampling of HIV-infected women does, however, provide us with insights as to differences in FI between HIV-infected and uninfected women.

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrates strong reliability, internal validity and contextual fidelity of measures of FI obtained using the IFIAS from HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women. We encourage other researchers to use and validate the IFIAS in other settings and among other populations (e.g. the elderly, lactating women) and to compare scores and prevalence of FI categories obtained with the IFIAS with those obtained using the HFIAS.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the GRRH administration in allowing them to conduct the study at the hospital’s antenatal care clinic and providing space for the research team within the hospital buildings. The authors thank Sophie Becky Ajok, the coordinator for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services at GRRH antenatal clinic, for helping them recruit pregnant women to the study. They also thank PRENAPS Uganda staff: Stella Adoch, Gladys Acayo, Winifred Achoko, Daniel Acidri and Claire Biribawa, for their dedication and hard work on this study. Lastly, they gratefully acknowledge Rebecca Stoltzfus, Patsy Brannon and Saurabh Mehta for comments on earlier drafts. Financial support: Funding was provided by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Feed the Future Innovation Laboratory for Collaborative Research in Nutrition for Africa (award number AID-OAA-L-10-00006 to Tufts University). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of USAID. S.L.Y. was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number K01 MH098902). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: B.K.N., S.L.Y., J.A. and J.K.G. conceived and designed study. B.K.N., H.K. and A.A. supervised data collection. H.K. conducted cognitive interviews. B.K.N. and S.L.Y. performed all the data analyses. B.K.N. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: Cornell University Institutional Review Board and Gulu University Institutional Review Committee approved the study protocol. The permission to carry out the study in Uganda was granted by the Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology. Written informed consent was sought from all study subjects before they were enrolled into the study.