Overweight and obesity in childhood may lead to multiple adverse consequences that can impact a child’s physical and psychosocial development( Reference Farpour-Lambert, Baker and Hassapidou 1 ). The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents has increased by about 40 % in most Western countries between 1980 and 2013( Reference Ng, Fleming and Robinson 2 ). At the same time, a steeper increase, of about 60 %, has been observed in emerging economies( Reference Ng, Fleming and Robinson 2 ). As a response to these rising rates, several studies have addressed the aetiology of childhood obesity, in order to inform early prevention strategies( Reference Lobstein, Jackson-Leach and Moodie 3 ). When exploring the aetiology of obesity much emphasis has been placed on the impact of environmental and behavioural changes( Reference Lobstein, Jackson-Leach and Moodie 3 – Reference Mattes and Foster 5 ) that influence nutrition and physical activity( Reference Biro and Wien 6 ). Young children are highly dependent on their parents for food provision, and parental feeding practices may thus have a profound effect on children’s eating behaviours and weight status( Reference Ventura and Birch 7 – Reference Birch and Davison 11 ).

In Sweden, the prevalence of childhood obesity is about 4 %, compared with about 8 % in Southern Europe; on the population level, childhood obesity is less pronounced in Sweden than in other Western and European countries( Reference Ng, Fleming and Robinson 2 ). Moreover, recent epidemiological studies have found that childhood obesity is stabilizing and leveling off in Sweden although the social gradient has become more evident( Reference Rokholm, Baker and Sorensen 12 – Reference Sjoberg, Moraeus and Yngve 14 ). Weight disparities between children of Swedish background and children of first- or second-generation migrant background persist: in Sweden, children of Turkish, Iranian and South American background have up to three times higher odds of developing overweight or obesity( Reference Besharat Pour, Bergstrom and Bottai 15 , Reference Khanolkar, Sovio and Bartlett 16 ).

Most research studies on obesity-related parental feeding practices focus on three constructs: restriction, pressure to eat and monitoring( Reference Birch, Fisher and Grimm-Thomas 17 , Reference Musher-Eizenman and Kiefner 18 ). High levels of restriction, characterized by a high degree of parental regulation of the types and amounts of food consumed by children, have been associated with children’s increased eating in the absence of hunger, higher food responsiveness and lower responsiveness to satiety cues( Reference Birch, Fisher and Davison 19 – Reference Rollins, Loken and Savage 23 ). High levels of pressure to eat, a construct that describes pushing a child to eat without prioritizing his or her internal satiety cues, have been related to fussiness, pickiness and limited interest in food, along with reduced appetite( Reference Jansen, Roza and Jaddoe 22 , Reference Galloway, Fiorito and Lee 24 – Reference Galloway, Fiorito and Francis 26 ). Restriction and pressure to eat have been associated with children’s weight status in numerous studies( Reference Rodgers, Paxton and Massey 27 – Reference Farrow, Blissett and Haycraft 31 ), although a few studies have not found such associations( Reference Gregory, Paxton and Brozovic 25 , Reference Hurley, Cross and Hughes 32 , Reference Rhee, Coleman and Appugliese 33 ). Monitoring is a construct characterized by keeping track of a child’s food consumption. Although monitoring has been associated with lower food approach( Reference Jansen, Roza and Jaddoe 22 ), research on monitoring has been less extensive and less conclusive( Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo 34 ).

Previous research has identified several correlates of parental feeding practices, including parents’ perceptions of their children’s weight status and concerns about their children being overweight or having abnormal appetite( Reference Ek, Sorjonen and Eli 35 – Reference McPhie, Skouteris and Daniels 39 ). Parental feeding practices are embedded in broader sociocultural contexts, reflecting social norms and culturally conditioned values and attitudes( Reference Bornstein 40 , Reference Patrick, Hennessy and McSpadden 41 ). Feeding practices are thus influenced by perceptions of desirable weight status and body shape, which may vary substantially according to sociocultural norms( Reference Regber, Novak and Eiben 42 ) and socio-economic status( Reference Sjoberg, Lissner and Albertsson-Wikland 43 ). Experiences associated with socio-economic hardship, such as food insecurity, poverty and hunger, have also been linked to parental feeding practices( Reference Kaufman and Karpati 44 ).

Despite the important socio-economic and sociocultural dimensions of parental feeding practices, most studies of parental feeding have been conducted among largely ethnically homogeneous, middle-class Western populations( Reference Ventura and Birch 7 ). Only a few studies (four in the USA and one in Germany and the UK), all with rather small samples, have focused on differences in controlling feeding practices among parents of different ethnic background; these studies found that controlling feeding practices are used less frequently among white US( Reference Cardel, Willig and Dulin-Keita 45 – Reference Wehrly, Bonilla and Perez 48 ) and white European parents( Reference Blissett and Bennett 49 ), compared with parents of minority ethnic background. Studies with larger samples, including parents from migrant backgrounds, are needed in order to understand associations between feeding practices and parental ethnic, cultural and national backgrounds, and thereby inform contemporary public health efforts in Europe.

The aim of the present study was to investigate associations between maternal country of birth and feeding practices in a large multicultural sample in Sweden. Specifically, the study examined associations between maternal origin and self-reported restriction, pressure to eat and monitoring practices, and assessed the influence of child and maternal characteristics as potentially relevant confounders. Based on research conducted in comparable European settings, we hypothesized that mothers born outside Sweden are more likely to engage in controlling feeding practices( Reference Blissett and Bennett 49 ).

Methods

Setting, participants and data collection

The total sample included 1325 mothers of children aged 4 to 7 years. Data were collected through the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ)( Reference Birch, Fisher and Grimm-Thomas 17 ) and a background questionnaire, which included questions regarding sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics of children and mothers; all distributed questionnaires were in Swedish. Participants were recruited through three groupings: a population-based sample in Malmö, a school-based sample in Stockholm and a clinically based sample in Stockholm. In all three groupings, responses were collected by mail. In Malmö, the Swedish Population Registry was used to recruit mothers; 876 out of the total of 3007 mothers of 4-year-olds participated in the study (response rate 29 %)( Reference Nowicka, Sorjonen and Pietrobelli 50 ). In Stockholm, the school-based sample targeted five schools and twenty pre-schools from areas with low, medium and high prevalence of obesity (compared with rates in Stockholm county); 432 out of 931 parents participated (response rate 46 %)( Reference Ek, Sorjonen and Eli 35 , Reference Ek, Sorjonen and Nyman 51 ). In the present study we used only data provided by mothers (n 351 in total). We added a clinically based sample in order to identify differences between parents of overweight or obese children and parents of normal-weight children. This sample consisted of baseline data from mothers of ninety-eight children with obesity aged 4 to 6 years. The children were referred by primary health-care centres across the county to an ongoing randomized controlled childhood obesity trial (NCT01792531)( Reference Ek, Chamberlain Lewis and Ejderhamn 52 ). The response rate was 87·5 %. The recruitment process and data collection procedures have been described in detail elsewhere for the Malmö sample( Reference Nowicka, Sorjonen and Pietrobelli 50 ) and for the Stockholm samples( Reference Ek, Sorjonen and Eli 35 , Reference Ek, Sorjonen and Nyman 51 , Reference Ek, Chamberlain Lewis and Ejderhamn 52 ).

Parental feeding practices

CFQ is an established, self-administered, seven-factor questionnaire assessing parental feeding practices, beliefs and attitudes related to obesity proneness among children and adolescents( Reference Birch, Fisher and Grimm-Thomas 17 ). The Swedish version of CFQ has been validated using confirmatory factor analysis and an optimal fit was obtained after excluding two questions regarding parental reward( Reference Nowicka, Sorjonen and Pietrobelli 50 ). Restriction, pressure to eat and monitoring are all CFQ factors. Restriction (Cronbach’s α=0·81) was measured by six items:

-

1. ‘I have to be sure that my child does not eat too many sweets (candy, ice cream, cake or pastries)’;

-

2. ‘I have to be sure that my child does not eat too many high-fat foods’;

-

3. ‘I have to be sure that my child does not eat too much of his/her favourite foods’;

-

4. ‘I intentionally keep some foods out of my child’s reach’;

-

5. ‘If I did not guide or regulate my child’s eating, he/she would eat too many junk foods’; and

-

6. ‘If I did not guide or regulate my child’s eating, he/she would eat too much of his/her favourite foods’.

The response options were scored: 1=‘disagree’, 2=‘slightly disagree’, 3=‘neutral’, 4=‘slightly agree’, 5=‘agree’.

Pressure to eat (Cronbach’s α=0·69) was measured by four items:

-

1. ‘My child should always eat all of the food on his/her plate’;

-

2. ‘I have to be especially careful to make sure my child eats enough’;

-

3. ‘If my child says “I am not hungry”, I try to get him/her to eat anyway’; and

-

4. ‘If I did not guide or regulate my child’s eating, he/she would eat much less than he/she should’.

The response options were scored: 1=‘disagree’, 2=‘slightly disagree’, 3=‘neutral’, 4=‘slightly agree’, 5=‘agree’.

Monitoring (Cronbach’s α=0·77) was measured by three items:

-

1. ‘How much do you keep track of the sweets (candy, ice cream, cake, pies, pastries) that your child eats?’;

-

2. ‘How much do you keep track of the snack food (potato chips, Doritos, cheese puffs) that your child eats?’; and

-

3. ‘How much do you keep track of the high-fat foods that your child eats?’.

The response options were scored: 1=‘never’, 2=‘rarely’, 3=‘sometimes’, 4=‘mostly’, 5=‘always’.

Another CFQ factor is concern about child weight; in the present study, concern about child weight (Cronbach’s α=0·86) was examined as a potential confounder. It consisted of three items:

-

1. ‘How concerned are you about your child eating too much when you are not around him/her?’;

-

2. ‘How concerned are you about your child having to diet to maintain a desirable weight?’; and

-

3. ‘How concerned are you about your child becoming overweight?’.

The responses options were: 1=‘unconcerned’, 2=‘a little concerned’, 3=‘concerned’, 4=‘fairly concerned’, 5=‘very concerned’.

Mean scores for each subscale were calculated; for each practice, higher scores represented more frequent use.

Background characteristics

A sociodemographic and anthropometric questionnaire was designed using items from established instruments. Data were collected on children’s age (in years), gender (boy or girl), height (in centimetres) and weight (in kilograms), and on mothers’ age (in years), height (in centimetres), weight (in kilograms) and level of education (more than 12 years or less than 12 years). Mother’s country of birth was self-reported in the background questionnaire based on the question ‘In which country were you born?’, with two answer options: ‘I was born in: (i) Sweden, (ii) another country, please specify’.

BMI (kg/m2) was calculated for children and their mothers, and was then used to establish the categories of overweight/obese and normal weight. The mothers’ weights and heights were self-reported in all samples. The children’s weights and heights were self-reported in the population-based non-clinical samples and measured by trained health-care professionals in the clinical sample. Child weight categories were created using age- and gender-specific international cut-offs for BMI( Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal 53 ).

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented as means (for continuous variables) and percentages (for categorical variables). Taking into consideration the large sample size (n 1325) and implications of the central limit theorem for normality in larger sample sizes, parametric tests were chosen. One-way ANOVA and χ 2 analyses were performed in order to explore possible differences in continuous and categorical variables across the groups established through mother’s place of birth. Once statistical significance was attained through ANOVA, post hoc analyses were performed using Bonferroni tests for multiple comparisons, in order to identify differences in continuous variables across the groups based on mother’s place of birth (these results are not reported in the present paper). Multiple linear regression was carried out, with restriction, pressure to eat and monitoring as dependent variables and mother’s place of birth as the primary exposure variable, to test the crude (Model I), partly adjusted (for child weight, Model II; and for concern about child weight, Model III) and fully adjusted models (Model IV). Unstandardized regression coefficients (b) were interpreted as the difference in scores between the reference group (Swedish-born mothers) and each of the three categories (Nordic/Western European-born, Eastern/Southern European-born and non-European-born). The confounders included child’s age, gender and weight status and mother’s age, weight status, level of education and concern about child weight. All P values <0·05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0.

Results

Study population

Table 1 provides an overview of the seventy-three countries, including Sweden, represented in the sample. Out of 1325 participating mothers, forty-one mothers did not indicate their country of origin and thus the total valid sample includes 1284 mothers. Of the mothers, 923 were born in Sweden, 159 were born in a European country other than Sweden and 202 were born outside Europe. No country of origin, except Sweden, was represented by more than 5 % of the whole sample.

Table 1 Mothers’ reported countries of origin, grouped by sociogeographic similarities, in the sample of mothers (n 1325) of children aged 4–7 years, Malmö and Stockholm, Sweden

Country of origin not reported: n 41.

† Included in the ‘Nordic/Western European’ group due to sociocultural similarities.

Mothers born in Europe were from thirty countries. The most represented European country was Denmark (thirty mothers), followed by Poland (twenty-one mothers). Mothers who were born outside Europe had origins in forty-two countries. The Middle East and North Africa region was the most represented, with 114 mothers from twelve countries, comprising 9 % of the valid cases; fifty-nine mothers were born in Iraq, which was the most represented country outside Europe.

Based on sociogeographic similarities and group size we created four sub-samples: (i) mothers born in Sweden (n 923); (ii) mothers born in a Nordic country or in Western Europe (including the USA and Australia, due to sociocultural similarities; n 70); (iii) mothers born in Eastern or Southern Europe (including Russia; n 93); and (iv) mothers born in the Middle East and North Africa, Asia, Latin America or sub-Saharan Africa, which we grouped under the heading of non-European-born (n 198).

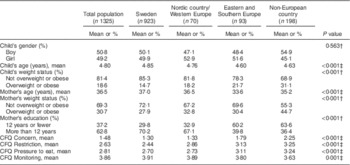

Table 2 shows the descriptive characteristics of the total sample and of the four sub-samples. Significant differences were found between the four sub-samples in children’s and mothers’ weight status and mothers’ education level. Mothers born in Sweden had a higher education level and lower levels of overweight and obesity in comparison with the mothers from the other three sub-samples. Swedish-born mothers reported the lowest level of concern about child weight, the lowest level of restriction and pressure to eat, and the highest level of monitoring practices, compared with mothers from the other three sub-samples.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics of the study population of mothers (n 1325) of children aged 4–7 years, Malmö and Stockholm, Sweden

CFQ, Child Feeding Questionnaire.

P value: significance level is 0·05.

Includes n 41 where country of origin was not reported.

† Chi-square test for categorical variables.

‡ One-way ANOVA for continuous variables.

Parental feeding practices

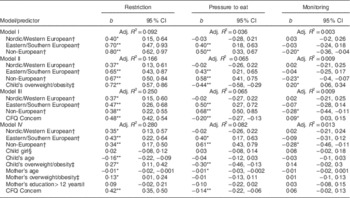

Restriction

Table 3 shows the results of the multiple linear regression analyses. Maternal origin was found to explain 9 % of the variance in restriction for Model I, the crude model. In Model II (adjusted for child’s weight status), the explained variance increased to 17 %. In Model III (adjusted for maternal concern), the explained variance increased to 25 %. In the fully adjusted model, the explained variance was 28 %. This indicates that child weight and maternal concern seem to be more important than mothers’ characteristics, such as age, weight status and education, in influencing feeding practices. Among the studied variables, maternal concern about child weight was highly influential. The first two models showed similar patterns with regard to the effect of mother’s country of birth (Nordic/Western European-born, Eastern/Southern European-born and non-European-born: b=0·40, 0·70 and 0·80 for the crude model and 0·37, 0·65 and 0·67 for the model adjusted for child’s weight status, respectively). However, adjusting for concern resulted in a different pattern; this pattern remained consistent after adjusting for all other confounders (b=0·37, 0·47 and 0·38 for the model adjusted for concern, and 0·35, 0·43 and 0·34 for the fully adjusted model, respectively). This indicates that concern about child weight accounts for some of the effect of maternal origin on restriction. For example, the difference in maternal concern can explain 52 % ((0·80 – 0·38)/0·80=0·52) of the difference in restriction between Swedish-born and non-European-born mothers.

Table 3 Crude and adjusted unstandardized regression effects (b; with 95 % confidence intervals) when predicting feeding practices from children’s and mothers’ characteristics in the total sample of mothers (n 1325) of children aged 4–7 years, Malmö and Stockholm, Sweden

CFQ, Child Feeding Questionnaire.

Includes n 41 where country of origin was not reported.

*P<0·05, **P<0·001.

† Compared with Swedish-born mothers.

‡ Compared with normal weight.

§ Compared with male child.

|| Compared with ≤12 years.

Moreover, in the fully adjusted model, weight status and the age of both the child and the mother were important. Child’s (b=0·27; 95 % CI 0·11, 0·42) and mother’s (b=0·13; 95 % CI 0·01, 0·24) weight status were positively associated, while child’s (b=−0·16; 95 % CI −0·22, −0·09) and mother’s age (b=−0·01; 95 % CI −0·02, −0·001) were negatively associated with restriction.

Pressure to eat

Maternal origin explained 3·6 % of the variance in the use of pressure to eat (Table 3). The explained variance increased to 6·5 % when adjusting for child’s weight status. Adjusting for concern yielded the same explained variance of 6·5 %. In the fully adjusted model, the variance increased to 8·2 %. In contrast, for pressure to eat, the effect of mother’s country of birth showed a consistent pattern, with Swedish- and Nordic/Western European-born mothers demonstrating the lowest values and non-European-born mothers demonstrating the highest values. In all models, no significant differences were observed between Swedish-born mothers and Nordic/Western European-born mothers with regard to pressure to eat. Mothers born in Eastern/Southern Europe had higher scores on pressure to eat, and non-European-born mothers had the highest scores. As in the case of restrictive feeding practices, child weight status and maternal concern about child weight were most influential. In the fully adjusted model, child’s weight status (b=−0·30; 95 % CI −0·46, −0·13) was negatively associated with pressure to eat, as was maternal concern about child weight (b=−0·14; 95 % CI −0·22, −0·06). Maternal age, education and BMI had weak associations with pressure to eat in Model IV.

Monitoring

In comparison with restriction and pressure to eat, the explained variance in monitoring was much lower in all models. The explained variance reached 1·3 % in the fully adjusted model (Table 3). Non-European-born mothers scored significantly lower in monitoring compared with Swedish-born mothers in all models. In Model II (adjusted for child’s weight status), child’s weight status was positively associated with use of monitoring (b=0·20; 95 % CI 0·06, 0·34). In Model III (adjusted for maternal concern), concern was also positively associated with use of monitoring (b=0·09; 95 % CI 0·03, 0·15); however, neither of these two confounders was significantly associated with monitoring in the fully adjusted model. Child’s gender and maternal education were not associated with monitoring.

Discussion

The present study is the first to investigate differences in controlling feeding practices between Swedish-born and non-Swedish-born mothers. The study accounted for potential confounding variables, including mother’s education and weight status, child’s gender and weight status and mother’s concern about child weight, while examining potential associations between mother’s region of origin – as defined through groupings by country of birth – and feeding practices. The analysis found significant associations between mothers’ migrant backgrounds and their feeding practices. Specifically, the analysis found that non-Swedish-born mothers, whether European-born or non-European-born, were more likely to report using restriction. In contrast, Swedish-born mothers and Nordic/Western European-born mothers reported similar levels of pressure to eat; these levels were lower in comparison with mothers born in Eastern/Southern Europe and mothers born outside Europe. Among the potential confounding variables, child’s weight status and concern about child weight were the most influential. Specifically, maternal concern about child weight accounts for some of the effect of maternal origin on restriction.

Compared with restriction and pressure to eat, the analyses showed much smaller differences between the groups regarding monitoring. In all four groups, most mothers scored higher on monitoring than on the other two practices, possibly reflecting the social desirability of endorsing monitoring practices. This ceiling effect made it difficult to examine associations between maternal background and monitoring, due to the limited variance of the results. Thus, the remainder of the discussion focuses on the analysis of relationships between maternal background, restriction and pressure to eat.

The current study extends the growing body of research on parental feeding practices by linking feeding practices and maternal migrant backgrounds. Only one other European study explored feeding in a multicultural context( Reference Blissett and Bennett 49 ). The study, which involved British and German mothers of children aged 2–12 years, found that German participants of Afro-Caribbean origin used restrictive feeding practices more often and monitoring less often than white German-born and UK-born participants. In another multicultural context, a US study showed that restrictive feeding was higher among Hispanic mothers of pre-school children, compared with non-Hispanic white mothers( Reference Worobey, Borrelli and Espinosa 47 ). Another study based in the USA, with slightly older parents, also showed that Hispanic parents endorsed the highest levels of restriction and pressure to eat, while non-Hispanic white parents endorsed the lowest levels( Reference Cardel, Willig and Dulin-Keita 45 ). However, while the aforementioned studies focused on ethnicity as a variable, the present study is the first to examine associations between migrant background and feeding practices.

There are three possible reasons why non-Swedish-born mothers report higher use of controlling feeding practices. First, controlling feeding practices may reflect culturally conditioned modes of parental communication with children. In a cross-cultural study that compared US families of diverse ethnic backgrounds with Swedish families, clear differences were observed in the dynamics of play between parents and infants, with US families showing a much higher interaction tempo than Swedish families( Reference Hedenbro, Shapiro and Gottman 54 ). Interestingly, the researchers observed that the US children were not overwhelmed by the higher tempo and that the Swedish children were not understimulated by the lower tempo. Similarly, the perception and reception of feeding practices may be culturally conditioned, and it is important to note that most studies where controlling feeding practices were found to be counterproductive were conducted among white US families, with negative influences particularly pronounced for girls( Reference Birch, Fisher and Davison 19 ). In other studies, especially those conducted among Hispanic and African-American families, no link was observed between the level of controlling feeding practices and weight gain in children( Reference Cachelin and Thompson 46 , Reference Powers, Chamberlin and van Schaick 55 , Reference Robinson, Kiernan and Matheson 56 ). It is possible, then, that controlling feeding may not substantially disrupt children’s self-regulation of appetite in an environment where controlling feeding practices are more common and have fewer negative connotations.

Another possible interpretation of the study’s findings is that parents are more likely to employ controlling feeding practices when facing stressful situations. Studies have shown links between stress and feeding( Reference Gemmill, Worotniuk and Holt 57 ), and between stress and childhood obesity( Reference Shankardass, McConnell and Jerrett 58 ). Furthermore, in the related area of parental mental health, studies have found associations between parental depression or anxiety and feeding practices( Reference Gemmill, Worotniuk and Holt 57 , Reference El-Behadli, Sharp and Hughes 59 – Reference Hurley, Black and Papas 63 ). It is important to note that behavioural changes caused by depression and stress may differ( 64 ). Symptoms may vary considerably depending on the context and length of depressive or stressful periods. Because experiences of migration are associated with increased long-term stress( Reference Ornelas and Perreira 65 , Reference Arbona, Olvera and Rodriguez 66 ) and structural vulnerabilities, parents may be less able to be attentive to children’s needs and may engage in pressuring or restrictive feeding practices as a result. The results of our recent analysis of associations between sense of coherence (a concept linked to resilience to stress), parental feeding practices, parental socio-economic status and parental migrant origin support this suggested nexus between migration, stress and controlling feeding( Reference Eli, Sorjonen and Mokoena 67 ).

Possible regional differences in concern about child weight offer a further explanation of differences in parental feeding practices. Our results suggest that variations in controlling feeding practices are partly explained by differences in the weight status of children and, even more so, by maternal concern about child weight; notably, in the case of restriction, maternal concern overrides the effect of maternal origin. In our study, higher proportions of non-Swedish-born mothers reported concern over child weight. These results are in line with a 2013 study that analysed data from eight European countries and found that about half of parents in Southern Europe were concerned about their children’s potential for unhealthy weight, in comparison with one-third of parents in Northern and Central Europe( Reference Regber, Novak and Eiben 42 ). Of note, large proportions of parents, especially in Southern Europe, were concerned about their children’s potential for both underweight and overweight. The authors argue that ‘having both concerns may imply the presence of a more universal uneasiness, of which weight concerns may be just one part’( Reference Regber, Novak and Eiben 42 ). Such regional differences may reflect both specific anxieties about eating, weight and the body, and anxieties born of economic inequality and uncertainty( Reference Offer, Pechey and Ulijaszek 68 ). As the mothers of non-Swedish origin who participated in our study were able to complete the questionnaire in Swedish – suggesting they had gone through some acculturative processes – it is also possible that increased maternal concern about child weight was accentuated by integrating into Swedish society, where emphasis is placed on lean body weight and appearance( Reference Brewis, Wutich and Falletta-Cowden 69 ).

The present study has several strengths and limitations. The study has a larger sample (n 1325) than previous studies that examined associations between parental national or ethnic background and controlling feeding practices. The large sample and the diversity of participants’ birthplaces (a total of seventy-two countries, apart from Sweden), in combination with the use of a population registry, make the study particularly robust. Since detailed Swedish registers are widely accessible, the final sample was found to reflect demographic aspects measured on the regional level, with the exception of level of education( 70 ). The study’s main limitation was the use of self-reports to determine BMI in the population-based and school samples. Cultural values affect the reporting of weight and height( Reference Johnson, Bouchard and Newton 71 , Reference Wen and Kowaleski-Jones 72 ), such that overestimation and underestimation are possible, especially for those children who have developed obesity( Reference Himes 73 , Reference Huybrechts, Himes and Ottevaere 74 ). Another limitation is lack of information about fathers’ countries of birth, as there might be some differences between families with one parent of non-Swedish background and families with two parents of non-Swedish background. An additional limitation may have been posed by language: the questionnaires were in Swedish only, which may have affected the quality of responses provided by participants who were not fluent in Swedish, and may have influenced the sample as well. Furthermore, the use of a cross-sectional design did not allow us to analyse whether mothers of non-Swedish origin have changed their feeding practices after moving to Sweden as a result of their migration experience. Finally, the interpretation of the results was limited by the parameters set for comparison; in the analysis, the participants’ countries of origin were grouped based on their geographic location (European and non-European) in most cases and sociocultural similarities in a few cases. The extent to which place of birth correlates with food and feeding practices can vary considerably between individuals, as well as between and within migrant groups, and it is likely that some non-Swedish-born participants were acculturated to aspects of the mainstream Swedish lifestyle, including dietary practices( Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser 75 ). As recent critiques have shown, acculturation is a multidimensional process that reflects migration type (e.g. economic v. asylum-seeking migration), the structures and values of the receiving society, the ethnic identification, values and practices of migrant groups, and the varying degrees of social inclusion and exclusion migrants encounter( Reference Schwartz, Unger and Zamboanga 76 ). Since acculturation is a non-linear process, the study did not assume a participant’s extent of acculturation based on demographic variables (e.g. years of residence in Sweden) and the analysis, therefore, did not aim to provide a subgrouping of non-Swedish-born participants based on extent of acculturation.

Future research

The findings suggest that additional research is needed to elucidate the reasons underlying the use of pressuring and restrictive practices by mothers of migrant backgrounds. Although recent research has identified parental resilience to stress( Reference Eli, Sorjonen and Mokoena 67 ) and parental socio-economic status( Reference Cardel, Willig and Dulin-Keita 45 ) as associated with feeding practices, it is also possible that child feeding practices are embedded in broader food-related practices( Reference Birch and Davison 11 ). Feeding practices are related to the preservation of cultural, communal and familial identities in the context of migration( Reference Sukovic, Sharf and Sharkey 77 , Reference Rabikowska 78 ), and it is still unknown how migration influences child weight status and parental concern about child weight. Differences within the relatively large groups of European-born and non-European-born mothers need to be explored further. Similarly, analysis by migration type (e.g. economic migration v. asylum seeking) would allow for a more nuanced understanding of associations between diverging processes of migration – upon the trauma and stress they involve – and parental feeding practices. Finally, future research should examine associations between parental migration and additional feeding practices, particularly encouragement and role modelling( Reference Gevers, Kremers and de Vries 79 ).

Conclusion

Differences in controlling feeding practices between Swedish-born and non-Swedish-born mothers were identified in a large sample of mothers of diverse countries of birth. Swedish-born and Nordic/Western European-born mothers were less likely to report using pressuring or restrictive feeding practices – practices that may promote unhealthy eating behaviours among children. Child weight and maternal concern about child weight were important confounding variables, especially for restriction. The study highlights the importance of national and migration background in influencing parental feeding practices. Future research should examine the processes that underlie differences between Swedish-born and non-Swedish-born mothers’ feeding practices. This could inform the development of inclusive interventions for promoting healthy feeding and eating practices in diverse societies, with sensitivity to the values and experiences of migrant parents, and an understanding of the hardships and structural barriers they encounter throughout the migration process.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank all the participating mothers, Anne Normann from the Childhood Obesity Unit in Malmö, students from Uppsala University (Eva Pettersson, Lisa Lundberg, Sandra Davidsson, Angelica Uhlander) who helped with data collection and data entry, and John Barthelemy from Skåne University Hospital who helped with data entry. Financial support: This work was supported from funds to P.N. by VINNOVA Marie Curie International Qualification (grant number 2011–03443), the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Society of Medicine, Swedish Saving Bank, Nestlé, Kellogg’s, Karolinska Institutet, Jerring Foundation, Samariten Foundation, Magnus Bergvall Foundation, Fredrik and Ingrid Thurings Foundation, Helge Ax:son Johnsson Foundation, ìShizu Matsumuraîs Donation, Foundation Frimurare Barnhuset in Stockholm, Foundation Barnavård and Crown Princess Lovisa Foundation for Pediatric Care. The funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: P.N. conceived the study, designed the statistical approach together with M.S., and supervised the coordination of the study and manuscript process. M.S. performed the statistical analyses and drafted the initial manuscript. K.E. interpreted data and edited the manuscript. A.E., L.L., J.N., C.M., A.P., C.-E.F., K.S. and M.S.F. made a substantial contribution to conception and design, data collection and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to reviewing and approving the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Regional Ethical Board in Lund (approval number 2009/362) and by the Regional Ethical Board in Stockholm (approval numbers 2011/1329-31/4, 2012/1104-32, 2012/2005-32, 2013/486-32 and 2013/1628-31/2). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.