1. INTRODUCTION

The editors’ aim in creating this themed issue of Organised Sound was to explore the resonances between questions raised by electroacoustic specialists and those taken up by scholars who work on the sounds of the pre-electric past. Since 1996, Organised Sound has been the leading journal for the study of electroacoustic music; for this issue we wanted to move beyond the traditional arena covered by ‘EA specialists’ and build a bridge between electroacoustic music studies and sound studies – by now a burgeoning field of inquiry that spans several disciplines, not least musicology and ethnomusicology, music theory and composition, anthropology, and sensory history. With this in mind, for the ‘New Wor(l)ds for Old Sounds’ issue, contributors were invited to apply the insights afforded by electroacoustic technologies, vocabularies, theories and practices to sounds and spaces created and used before the widespread adoption of electric sound.

When it came to setting a cut-off date for our call, the density of technological breakthroughs for electrified sound in the decades around 1900 presented us with a rich array of possibilities (Thompson Reference Thompson2002). We could have chosen 1895, the year in which American inventor Thaddeus Cahill first submitted a patent application (US 580035 A) for an electromechanical organ he dubbed the Telharmonium or, more prosaically, ‘The Art of and Apparatus for Generating and Distributing Music Electrically’. Another landmark year was 1905, when Max Kohl A.G., a German firm specialising in scientific instruments, introduced their Helmholtz Sound Synthesiser, one of several such devices built following designs by the German scientist and acoustician Hermann von Helmholtz (Pantalony Reference Pantalony2005; Wittje Reference Wittje2013). Or we could have reached back to 1865, when the German physicist and luthier Rudolph Koenig, working in Paris, advertised his own Helmholtz synthesiser, emphasising the ability to replicate the timbre of vowel sounds through the manipulation of overtones (Pantalony Reference Pantalony2009: 52–5).

Moving from the rarified world of scientific instruments to more publicly oriented technologies took us further into the twentieth century. On 2 November 1920, the first commercial radio station, Pittsburgh’s KDKA, crackled to life, broadcasting US presidential election returns in the contest between Warren Harding and James Cox (Hinds Reference Hinds1995: 3; Lewis Reference Lewis1992: 28). If Léon Theremin’s invention of his eponymous instrument in the Soviet Union in 1922 is an especially familiar milestone for specialists in electroacoustic music, the first commercial screening of motion pictures with sound-on-film technology the following year – Lee De Forest’s ‘Phonofilms’, premiered at New York’s Rivoli Theater – suggested new uses for electric sound in the context of mass entertainment (Wierzbicki Reference Wierzbicki2009: 86–7).Footnote 1 In 1924 German inventors Walter Schottky and Erwin Gerlach developed the ribbon microphone and ribbon speaker (Gerlach Reference Gerlach1924; Schottky Reference Schottky1924; Skudrzyk Reference Skudrzyk1954: 6), while across the Atlantic the first recordings using electric groove-cutting were made in Columbia’s New York lab, reaching the public in the form of the RCA Victor Orthophonic Victrola (Millard Reference Millard2005: 142–3). Other transformative developments were the release in 1927 of the first ‘talkie’, the American film The Jazz Singer, and the 1932 opening of the first concert hall wired for sound, New York City’s Radio City Music Hall (Thompson Reference Thompson2002: 229–31).

But we kept returning to the year 1925, and to a technological innovation that, although rarely foregrounded as a watershed in the history of electric sound, was to have profound and far-reaching repercussions. That year, American electrical engineer Chester Rice filed a set of patents that laid the groundwork for the development of the first commercial loudspeaker. Rice’s main patent describes an electromagnetic loudspeaker (US 1707570 A) with a corresponding amplification system (US 1728879 A), developed in collaboration with his colleague Edward Kellogg. In the patent filing, Rice also credits Kellogg’s Radio Receiving System (US 1584551, incorrectly cited as US 158455), with having a direct impact on his research. Together with an electric condenser (US 1714890 A) these patents made possible the development of the first loudspeaker to be sold commercially. Marketed by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) as the Radiola Loudspeaker Model 104, the loudspeaker promised its buyers nothing less than ‘acoustic perfection’.Footnote 2

2. NEW SOUND WORLDS

Adopting the terms commonly used today, the RCA Model 104 was an active speaker with built-in amplifier or, alternatively, a complete electroacoustic transducer: an instrument capable of converting an electric audio signal into audible sound (Millard Reference Millard2005: 145; Helmreich Reference Helmreich2015). Such technical descriptors gloss over what was most remarkable about RCA Model 104. As Kellogg and Rice stressed when they presented their new invention to the 1925 Conference for the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, they had developed the first loudspeaker capable of electronically producing all the frequencies necessary for replicating the full spectrum of audible sound (Kellogg and Rice Reference Kellogg and Rice1925: 464). In short, as RCA underscored in their advertising campaigns, their Model 104 was the first speaker that could reproduce sound accurately. It opened up new sound worlds for listeners, and compelled the development of new words to describe the production and reproduction of sound electronically. What better emblem, we thought, of the transition to a world resonating with sounds both acoustic and electric – and what better jumping-off point for a themed issue bridging the fields of electroacoustic music and sound studies?

A series of responses from audio professionals and other experts is included in the paper by Kellogg and Rice Their colleague at RCA, John Preston Minton, who was later awarded patent US 1855582 A for his own loudspeaker, furnished his response with figures delineating six curves (generated using his own acoustic measurements) that demonstrated what he described as the multi-directional, ‘steady progress’ in sound reproduction technologies between 1921 and 1925 (Kellogg and Rice Reference Kellogg and Rice1925: 477). He summarised the main improvements as follows:

1. The extension of the range of response (i.e. loudness at various frequencies) to include both higher and lower frequencies.

2. The gradual elimination of the sharp peaks and depressions, i.e. uniformity of response.

3. The assurance of a more nearly equal response at all frequencies.

4. The reduction of non-linear distortion.

5. The introduction of pure low-frequency response.

Minton’s list celebrates advancements made collectively by the many people working to perfect the electronic reproduction of sound. Earlier in the piece, too, he gestures to individual and institutional interest in this area of inquiry, observing that ‘much credit for the gradual evolution of the loud speaker is due to many other works in this and the allied fields of voice, ear, and music analysis … from our universities and our industrial research laboratories’ (Kellogg and Rice Reference Kellogg and Rice1925: 477).

From the beginning, then, speakers embodied cross-disciplinary collaboration. Their successful development depended on the specialised knowledge of a diverse collection of experts: electrical engineers, specialists in magnetic design, mechanical engineers, chemical engineers – and, particularly before the advent of computers, musicians.Footnote 3 Because it was so challenging to measure and predict the sound coming from a specific transducer design, virtually all good transducers were designed in tandem with musicians who listened closely to the reproduced sound, and assessed it in comparison with the original signal (Meyer, personal communication 2018). The ‘fidelity’ of these electroacoustic marvels – literally, their ability to ‘faithfully’ reproduce sound – hinged in part on skills honed by many a practising musician.

3. NEW WORDS

New technologies gave rise to new words. Existing words for scientific concepts, and the names of existing scientific or musical instruments, were often combined or abbreviated. Cahill’s Telharmonium combined ‘telephony’ with ‘harmonium’, for example, while Radiola, a diminutive of ‘radio’, was also an abbreviated reference to the ‘radio music box’ it described.

An etymological exception is the word that gained widespread currency with the runaway success of RCA 104: ‘loudspeaker’ or, simply, ‘speaker’. Just what this electroacoustic transducer ought to be called was not a foregone conclusion, but the proposed solutions tended to be variations on the theme of an amplified human voice.Footnote 4 Kellogg and Rice described their invention using an evocative compound noun, ‘loud speaker’, and it appeared elsewhere as the hyphenated ‘loud-speaker’. In Germany, the scene of so much electroacoustic research, the equivalent expression ‘Lautsprecher’ also caught on. The notion of a device that ‘spoke loudly’ was not new, of course: in France in the early 1900s, the term ‘haut-parleur’ had been used to describe an amplified telephone (Lyle Reference Lyle1902). In 1884, the English expression ‘loud speaker’ is recorded in Britain, in what seems to have been an isolated occurrence; Bell Labs subsequently named their own transducer, used to amplify speeches, a ‘loud-speaker’.Footnote 5 Since Kellogg and Rice’s invention reached out to a broader market than did the devices developed for public address systems, it is probably via the RCA 104 that the term ‘loud speaker’ and its variants (i.e. ‘loud-speaker’, ‘loudspeaker’) entered common parlance.

Somewhat surprisingly given the impact of the invention it describes, the paper by Kellogg and Rice, published as ‘Notes on the Development of a New Type of Hornless Loud Speaker’, has not figured regularly in musicological scholarship. It has, however, been cited more frequently in audio engineering and acoustical studies – at least 60 times since its publication according to Google Scholar which, while admittedly not providing a comprehensive sampling, nonetheless gives a sense of the disparity. The number of citations increases slightly when we include references in which the author, intentionally or not, replaces ‘loud speaker’ with ‘loudspeaker’. In their patent filing, Kellogg and Rice used ‘loud-speaker’ and ‘loud speaker’ interchangeably, but not the verb-plus-noun ‘loudspeaker’.

These forms differ significantly in their implications. The original, ‘loud speaker’, could be interpreted either as two words, that is, an adjective modifying the noun (‘speaker’, with the stress falling on the noun), or alternatively, as a single word (with the stress falling on the first syllable).Footnote 6 This latter formation is what linguists term a ‘synthetic compound’ or ‘compound noun’. Opting for ‘loud-speaker’ or ‘loudspeaker’ obviates the question of whether the name of the device is a single word or two. As a single word, it evokes a new entity altogether – one that bears traces of the human voice but is not human itself. ‘Loudspeaker’ can describe a machine, in other words, but not a human. Ultimately, it was this ‘android’ form that caught on.

Although all these variants cluster within the same lexicographical unit, their popularity waxed and waned at different times. According to Google’s Ngram viewer,Footnote 7 occurrences of ‘loud speaker’ in published articles peaked in 1926; it is worth noting in this regard that Kellogg and Rice used this form in their paper (i.e. ‘hornless loud speaker’), as did Minton in his response. The hyphenated form ‘loud-speaker’ peaked later, in 1944, and the synthetic form ‘loudspeaker’ appears to have peaked in 1956.Footnote 8 Just when the abbreviated form ‘speaker’ came into its own is less clear, but by 1953 it was available to be wielded casually by Roald Dahl: a character in ‘My Lady Love, my Dove’, from his short story collection Someone Like You, says archly to her husband, ‘Maybe the great radio engineer doesn’t know how to connect the mike to the speaker?’ (Dahl Reference Dahl1953: 66).Footnote 9 Still harder to track is the relative frequency of these variants in printed advertising – the medium that surely had the greatest impact on usage among members of the general public. RCA advertisements in the late 1920s seem already to have tended towards the synthetic compound ‘loudspeaker’.

4. NEW WORLDS FOR OLD SOUNDS

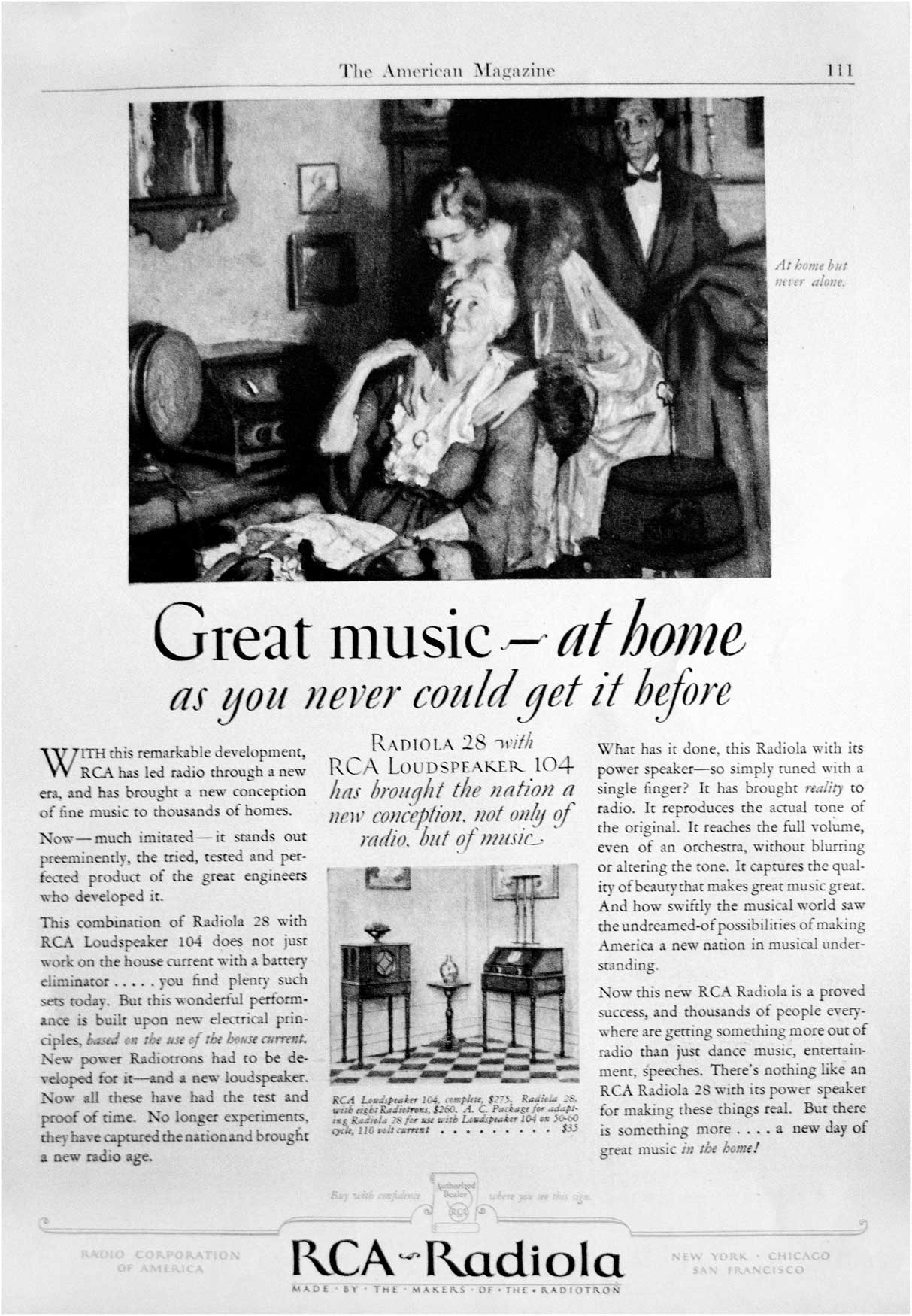

Initially, at least, Kellogg and Rice imagined the primary use of their speaker to be in the concert hall, writing explicitly that ‘[i]t is, therefore, not a household device, its field of application being rather in auditoriums’ (Kellogg and Rice Reference Kellogg and Rice1925: 468). RCA nevertheless marketed the new loudspeaker for domestic use, deploying such taglines as ‘Power – for home concerts’. A representative advertisement from the period, reproduced in Figure 1, humanises the machine. The intimate scene of a family gathered around the Radiola is accompanied by the tagline ‘At home, but never alone’,Footnote 10 while the text underneath declares hyperbolically that the RCA 104 power speaker

has brought reality to radio. It reproduces the actual tone of the original. It reaches full volume, even of an orchestra, without blurring or altering the tone. It captures the quality of beauty that makes great music great. And how swiftly the musical world saw the undreamed-of-possibilities of making America a new nation in musical understanding … [T]here is something more … a new day of great music in the home. (original emphasis)Footnote 11

Figure 1 Representative RCA Radiola advertisement from the 1920s. Reproduction courtesy of Margaret Schedel.

This new device claims to democratise the sounds of high art, bringing ‘great music’ into ordinary American households, without distortion. The invocation in the advertisement of music of the European classical tradition bears emphasising; RCA’s ads are targeted squarely at white America, where capital was concentrated.Footnote 12

As the RCA speaker brought the edifying sounds of European art music into the (affluent white) American home, it pointed confidently to a technological future in which America would lead the way. Another advertisement for the Radiola 28 (a radio) with RCA Loudspeaker 104 announces presciently that the pairing ‘has brought the nation a new conception, not only of radio, but of music’.Footnote 13 Still, what the inventors of this loudspeaker, and indeed the company that manufactured and sold it, could not have envisioned was a conception of music so radically new that it was completely dependent on loudspeakers: electroacoustic music.

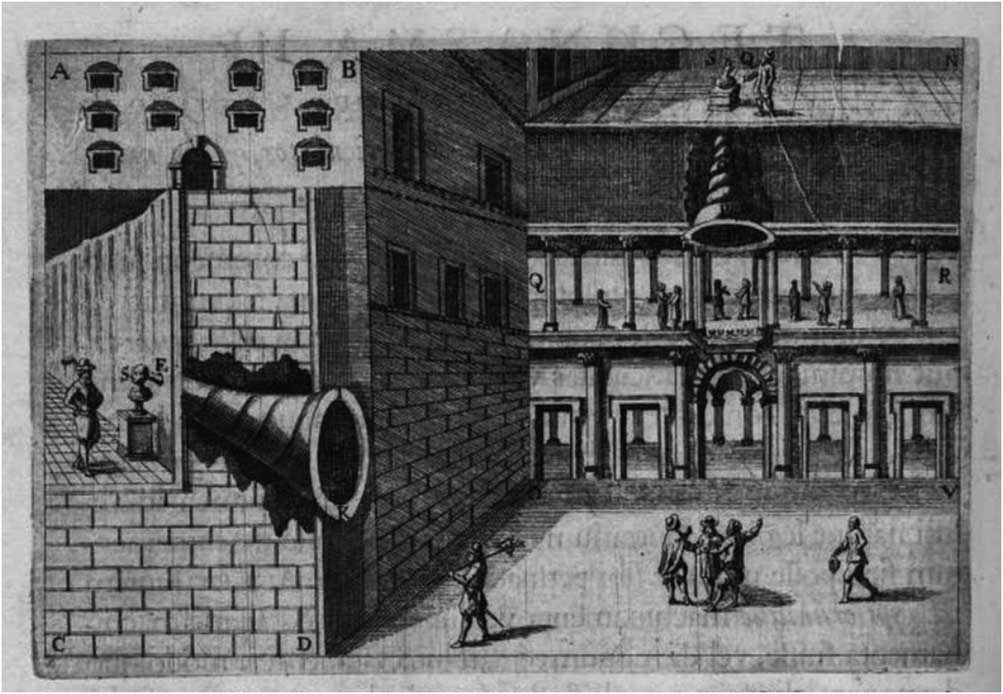

A productive link between our discussion of RCA Model 104 and sonic technologies of the pre-electric past can be made via the treatise Phonurgia nova (Kircher Reference Kircher1673) – roughly, New Sound-Making – written by one of the most celebrated of early modern thinkers, the German Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher (1601–08).Footnote 14 Phonurgia nova describes a vast array of sound-producing instruments and amplifying devices, real, historical and imagined: from architectural conduits for sound, such as whispering galleries (resulting from smoothly surfaced, ellipsoidal vaulted ceilings) to such acoustic illusions as talking statues (Figure 2; see also Spohr Reference Spohr2012 and Tronchin Reference Tronchin2009).

Figure 2 Athanasius Kircher, Phonurgia nova (Kempten, 1673: 162). Public domain.

Juxtaposing Kircher’s Phonurgia nova with the advertisements and scientific papers connected to RCA Model 104 makes obvious that the values that accrue to sound, and to the instruments that generate and amplify sound, are culturally and temporally contingent. The speakers patented as US 1707570 A and US 1728879 A were the copyrighted products of human ingenuity, exemplifying the rapid march of scientific progress. Sold as RCA Model 104, this technology could be consumed. Gathering around their very own Radiola, buyers supported and participated in a new age of technological discovery – and reaped its benefits. By the same token, Kircher’s treatment of sound-amplifying instruments reflects the Baroque preoccupation with the wondrous (i.e. meraviglia, merveilleux) – a preoccupation that figures prominently in one of the contributions to this special issue, Rebecca Cypess and Steven Kemper’s ‘The Anthropomorphic Analogy’, discussed in greater detail below. In a brief glossary appended to the main text, Kircher defines phonurgia as ‘the capacity to bring about the marvellous by means of sound’ (Kircher Reference Kircher1673: fol. Gg3r).Footnote 15 Indeed, the subtitle of his treatise boldly proclaims that he will describe the ‘Mechanico-Physical Wedding of Art and Nature, Conducted by the Phonosophical Groomsman’ (Conjugium mechanico-physicum artis et naturae paranympha phonosophia concinnatum): the union of the technological (i.e. that devised by humans) and the natural (i.e. that created by God), with Kircher as witness and guide. Phonurgia nova evidently captured the imagination of his contemporaries, and by the next decade it was made accessible to less learned readers – those who did not read Latin – with its translation into German as Neue Hall- und Thon-Kunst (New Art of Resonance and Sound)... (Kircher Reference Kircher1684).Footnote 16

Calling to mind the density of electroacoustic inventions in the years around 1925, there was a flurry of interest in sound and amplifying instruments in the 1670s and 1680s, intensified no doubt by the foundation of scientific societies such as the Royal Society in England (1660) and the Académie Royale des Sciences in France (1666). In 1677 for instance, natural philosophers in the Académie Royale determined the speed of sound to be roughly 356 m/s (in modern units; modern measurements place it at 343 m/s). Some years earlier, the English engineer and spy Samuel Morland authored Tuba Stentoro-Phonica, an Instrument of Excellent Use, as Well as at Sea as at Land (Morland Reference Morland1672), getting embroiled along the way in a dispute with Kircher over who ought to be credited with the invention of this marvellous ‘speaking trumpet’ (stentorophonicon; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2000: 113–16, Mancosu Reference Mancosu2006: 609–10).

But a more familiar seventeenth-century treatise, Johannes Kepler’s Harmonices mundi libri V (The Harmony of the World), printed in Linz in 1619, bridges the gap between sound in the pre-electric past and modern electroacoustic music. The treatise is justly celebrated for its presentation of Kepler’s third law of planetary motion. What is less often noted is that the universal ‘harmony’ Kepler describes is fundamentally musical:

[T]he motions of the heavens are nothing but a kind of perennial harmony (in thought not in sound) through dissonant tunings, … and tending towards definite and prescribed resolutions, individual to the six terms (as with vocal parts) and marking and distinguishing by those notes the immensity of time. (Kepler Reference Kepler1619, trans. Reference Kepler1997, 446)

While Kepler’s use of ‘harmony’ in this passage is explicitly theoretical, the treatise also includes an abundance of references to musica practica and the world of sounding music: snippets of Gregorian chant, a notated rendition of Ottoman cantillation, repeated references to Orlande de Lassus’s motet In me transierunt (from his Sacrae cantiones quinque vocem, 1562), and – not least – an appeal to composers to make audible the music of the spheres in a heliocentric universe. Kepler calls on his contemporaries to recreate in a six-voice motet the melodies of the six planets as they moved through the heavens, harmonious in their orbits.Footnote 17

In 1979, two professors at Yale University, John Rodgers (Geology) and Willie Ruff (Music), in partnership with computer specialist Mark Rosenberg, responded to Kepler’s challenge – but not with human voices. Using a computer sound synthesiser, specifically the IBM 360/91 computer housed at Princeton University, running the synthesis program MUSIC 4BF, they devised and recorded what they termed a ‘realization’ of Kepler’s data on planetary movement (Rodgers and Ruff Reference Rodgers and Ruff1979), updating it to include the three planets not yet discovered in Kepler’s lifetime. The resulting LP (Kepler Label LP 1571) was issued with a reprint of a companion article, ‘Kepler’s Harmony of the World: A Realization for the Ear’, which had appeared in the May 1979 issue of American Scientist. Where Kepler had imagined human singers replicating what was inaudible, Rodgers and Ruff used technology both to generate the sounds and to ensure their faithful reproduction. They send the listener to the sun, courtesy of hi-fi headphones and MUSIC 4BF: ‘High fidelity earphones greatly enhance the spatial effect of the general planetary movement around the Sun’, they write, before admonishing the reader: ‘Note that the positions of the planets change in their orbits in Stereo from side to side. Always play the recording in Stereo’ (LP 1571 liner notes).Footnote 18

The connections between the pre-electric and electrified sound worlds are, of course, aesthetic as well as technological. Kepler’s commitment to a rational universe – a cosmos ordered by ratio – also resembles the aesthetic positions articulated by Karlheinz Stockhausen in his increasingly universalist discussions of electroacoustic composition. Stockhausen closes his essay ‘The Concept of Unity in Electronic Music’ (Stockhausen Reference Stockhausen1962) with a passage that exemplifies his confidence in a mode of composition in which the parameters of timbre, pitch, intensity and duration are governed by a ‘common principle’. He argues that

if … it has become necessary … to bring all the spheres of electronic music under a unified musical time, and to find one general set of laws to govern every sphere of musical time itself, this is simply a result of the condition imposed by electronic music that each sound in a given work must be individually composed. (Stockhausen,Reference Stockhausen1962: 48)

Here and elsewhere, it is evident that for Stockhausen it was through electronics that the music of the spheres was to be made audible, because electronics made it possible at last to actually, and conceptually, coordinate ratios in a unified way. For Stockhausen as for Kepler, mathematically ordered music made perceptible the divine order of the universe. ‘God’, asserted Stockhausen in terms that would have been familiar to Kepler, ‘is the greatest musician of all times: the greatest composer’ (Stockhausen Reference Stockhausen1989: 114).

5. FUNDAMENTALS AND RESONANCES

In its very formation, the word ‘electroacoustic’ obviously implicates the electric. While we could have simply proposed a crossover issue between sound studies and electroacoustic music, we have chosen instead to be deliberately provocative, and to encourage our authors and readers to expand their conception to ‘follow Kircher’ as it were, and consider together the sounds of different times and places. The vocabulary and methodologies developed by electroacoustic musicians to build a sonic lexicon of timbre and space, research the sounds of the past and contextualise the impact of technology on sonic creativity are well suited to historically oriented sound studies, but we also wanted our authors to explore connections between disparate timeframes.

Our theme is potentially chaotic, encompassing as it does the vast territory of sound studies and the specialised field of electroacoustic music studies. Yet, just as we had hoped, a number of threads coalesce and run through the diverse contributions: the notion that the old and the new can contextualise each other; that sounds and sound instruments can index the relationships among humans, between humans and machines, and between humans and their environments; and that thinking sonically often means thinking across disciplines.

Evidence for a ‘sonic turn’ in and beyond the humanities is everywhere: in the calls for papers of recent interdisciplinary conferences, in the popularity of sound-oriented blogs, in the formation of sound studies interest groups in academic professional societies, in the collaborations of electroacoustic composers with social scientists, and, not least, in the purview of Organised Sound itself. Keywords in Sound (Novak and Sakakeeny Reference Novak and Sakakeeny2015) offers a ‘conceptual lexicon’ of words for sound, with entries delineating both the rich intellectual history and the theoretical valences of selected ‘keywords’; the disciplinary backgrounds of the contributors range from music’s various subdisciplines, to anthropology, to historians of texts and sound media.

Studies exemplifying a historicist turn to the sonic draw attention to the acoustic properties of ancient and early modern spaces, and those of more recent built environments (Atkinson Reference Atkinson2016; Blesser and Salter Reference Blesser and Salter2007; Fisher Reference Fisher2014); they search archival documents for the sounds of colonial encounter (Rath Reference Rath2005) and the hubbub of England in the Victorian period and earlier (Picker Reference Picker2003; Cockayne Reference Cockayne2007); they find traces of the noisy mediaeval city in manuscript illuminations (Dillon Reference Dillon2012); they document sound and its silencing to trace shifting urban identities and values (Bjisterveld Reference Bjisterveld2008; Thompson Reference Thompson2002); they investigate the properties of instruments and technologies, from monochords to metronomes, developed to chart interval space and measure musical time (Grant Reference Grant2014), to cassette tapes (Bohlman and McMurray Reference Bohlman and McMurray2017); they consider the collision of early recording technology with contemporary Western musical aesthetics (Rehding Reference Rehding2005).

Collaborative digital projects recreate past sound worlds: the ‘First Sounds’ website, created by audio historians Patrick Feaster and David Giovannoni, with others, recovers and makes available digitally the earliest known recorded sounds (Feaster and Giovannoni Reference Feaster and Giovannoni2008–18; Rawes 2008–Reference Rawes18). Other projects embed reconstructed sounds in 3D virtual space, as in Mylène Pardoen’s The Sound of Eighteenth-Century Paris, realised in collaboration with researchers from the Centre Interdisciplinaire de Réalité Virtuelle (CIREVE), the Évolution des Procédés et des Objets Techniques (Epotec) group and the Centre de Recherches Historiques-Laboratoire de Démographie et d’Histoire Sociale (CNRS/EHESS).Footnote 19 Others situate records (both aural and textual) of sound in specific locations, as with Ian Rawes’s ever-expanding London Sound Survey (Rawes 2008–Reference Rawes18, Reference Rawes2014). Data sonification, another bustling field of activity, now reaches into the pre-electric past. In time for the 400-year anniversary of the publication of The Harmony of the World (1619), music technologist Kelly Snook – heading a team of programmers, musicians, engineers, and artists – is producing yet another realisation of Kepler’s music of the spheres. Her ‘Kepler Concordia’ (Snook Reference Snook2017) is an instrument that embeds immersive ambisonic sonifications of his calculations within a distinctly twenty-first century Virtual Reality environment.

The interest in timbre, changing technologies and acoustics that animates these projects also drives the work of our authors. These six articles venture into vastly different regions of the sonic past, from singing birds as observed in Classical Antiquity, to organists in early modern Italy, to nineteenth-century orchestra machines, to shellac recordings in early twentieth-century India. Each article works through its words and its worlds in surprising and productive ways.

Gergely Loch’s ‘Between Szőke’s Sound Microscope and Messiaen’s Organ: The cultural realities of blackcap song’ starts with a description of a primordial sonic phenomenon, the song of the blackcap warbler. Birdsong figures prominently in the history of electroacoustic sound: ornithology was one of the first scientific fields to use biological acoustics, and Ottorino Respighi’s inclusion of a gramophone recording of nightingales in Pines of Rome (1924) is often cited for its pioneering combination of recorded sound with live performance. Loch, a musicologist, uses his own 2017 recording of the blackcap to tease out the dichotomy between sound-based and note-based analysis. He draws on descriptions of the blackcap’s song in natural history texts ranging from the relatively brief mentions in Classical Antiquity, to the more extensive discussions that began appearing in the sixteenth century and continued through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He uses these historical responses to contextualise two twentieth-century engagements with the blackcap’s song: the ‘sonic magnification’ of the song by self-described ornithomusicologist Péter Szőke using a ‘sound microscope’, and the more familiar translations of birdsong into music notation by composer and ornithophile Olivier Messiaen.

Birds were a favourite subject for builders of automata, and the mechanical nightingale was immortalised in Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘Nattergalen’. Fans of the science fiction television series Black Mirror will recognise in Andersen’s tale a familiar obsession with the technological, a preference for the mechanised and mechanical over the real. In their article ‘The Anthropomorphic Analogy: Humanizing musical machines in the early modern and contemporary eras’ musicologist Rebecca Cypess and music technologist/composer Steven Kemper delve deep into seventeenth-century theorisations of human bodies and musical instruments, before directing their attention to the present, using insights from early modern thought to contextualise current trends in embodied performance. Weaving together the writings of René Descartes with meditations by Giambattista Marino, treatises by the musicians Girolamo Diruta and Michael Praetorius, and images by Giovanni Battista Bracelli and Nicolas de Larmessin, the authors present case studies of humanoid musical robots and their counterpart: cybernetically augmented humans. Their work returns anthropomorphic analogies to the study of organology, reviving earlier embodied language that receded during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the advent of recorded sound and the increasing fascination with disembodied sound and the acousmatic veil.

Sharing this interest in organology and cybernetics, music theorist Jonathan De Souza’s ‘Orchestra Machines, Old and New’ examines the sonic and social affordances of orchestras – ‘modes of collective performance’ as he puts it – that either implicitly or explicitly operate as networks. De Souza’s juxtapositions of the technical and social, of human and non-human musical agents, of nineteenth-century orchestra machines with twenty-first-century machine orchestras, suggest in the first place that the abstraction (i.e. ‘network’) shared by the acoustic orchestra in its various manifestations (e.g. the vastly different orchestras of Haydn, Mahler and Count Basie; instrumental ensembles in non-Western traditions) and the electroacoustic orchestra in its various forms (e.g. the laptop orchestra or mobile phone orchestra) offers a productive means of comparing them. Identifying both varieties of collective music-making as systems connecting people and instruments (constrained, of course, in ways that shape actions, interactions, sounds and ideas), De Souza draws attention to the ethical questions that arise when we consider the relationships of power – that is, the politics – characteristic of these networks.

Where De Souza takes up networks and collectivities, sound artist and sound studies scholar Budhaditya Chattopadhyay focuses on dislocation and disembodiment in ‘Orphan Sounds: Locating historical recordings in contemporary media’. Chattopadhyay is interested specifically in the unmooring of sounds preserved on old media – early shellac and cylinder recordings from India – when they are redeployed in digital forms in a post-digital ‘convergent’ present: ‘old’ sounds set free in a world of ‘new’ media. He takes up questions of sonic localisation, stressing the increased fluidity of the relationship between sound and place when localised (and historical) sounds become un-sited and ‘timeless’ in the course of digitisation.

Chattopadhyay uses as case studies two of his own sound-based projects: ‘Story of a Forgotten Melody’ (2006), in which early twentieth-century recordings of music in the Bengali Bishnupur Gharana tradition were made available online; and ‘Eye Contact with the City’ (2011), a sound and video installation that juxtaposes ‘found sounds’, retrieved from shellac records and reel-to-reel tapes source in Bangalore flea markets, with the sounds of the urban present. If the ideal acousmatic signal exists outside of place, time and context, Chattopadhyay suggests that digitised audio samples from the past can become these ideal signals, freed from their original ‘object’ associations and free to acquire new meanings in a globally dispersed media environment. Bringing together perspectives from media archaeology, electroacoustic musicology and sound studies, Chattopadhyay thematises the interplay between old and new, and reminds the reader that old technology, too, was itself once new.

Although the first four articles concentrate on the pre-electric past, they would not have been out of place in previous themed issues on sonic imagery, embodiment, networked music, or situating the avant-garde. The next ‘on-theme’ article takes on a novel subject for this journal: its author uses an electroacoustic approach to discuss recordings of non-EA works that are not recontextualised in an electroacoustic sphere. In ‘Code-switching and Loanwords for the Audio Engineer: The flow of terminology from science, to music, to metaphor’, audio engineer/composer Nicolas Nelson focuses on the specialised language of audio engineers, and explores how field-specific words and expressions (e.g. ‘tinny’, ‘throwing bass’, ‘scratchy sound’) emerged and crossed over into everyday usage as engineers sought to describe sounds that could not be captured using pre-existing words. Particularly fascinating is the evolution of the word ‘range’, which initially included extra-musical sounds such as bow noise or the intake of breath.

It was not until 1966, with Pierre Schaeffer’s TARTYP (TAbleau Récapitulatif de la TYPologie) chart, that a systematic description of timbre was proposed – and to date it has not been widely adopted by audio engineers.Footnote 20 As machines made it possible to capture new sounds, the vocabulary slowly evolved to describe them. Nelson challenges the assumption that recordings faithfully reproduce an acoustic musical signal, and considers the evolution of musical and metaphorical discourse with the emergence of the specialised field of recording engineers.

Our final article, Will Schrimshaw’s ‘The Tone of Prime Unity’, likewise reaches beyond the explicit constraints of the initial call. That it nonetheless illuminates the tension between imagined non-electric worlds (here figured as ‘natural’) and the electrified environments in which we now live, serves as a reminder that chronological markers can become incidental in the face of conceptual problems. Schrimshaw takes up a distinctly utopian thread in R. Murray Schafer’s sonic philosophy, namely the concept of ‘the tonal center’ or ‘prime unity’ that Schafer posited in The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Drawing inspiration from pre-electric theorisations of sound’s metaphysical power – the music of the spheres, as well as the Indian notion of anaháta (i.e. that which is unstruck, unbeaten, or, more poetically, that which is unsounded) – Schafer proposed that a modern community naturally settles on, or tunes into, a single frequency which matches the frequency of the prevailing electrical signal (e.g. 60Hz in the United States; 50Hz in the United Kingdom). Schafer’s technologically dependent concept of prime unity suggests a utopianism rooted in the post-industrial world that stands in contrast to his well-documented preference for the acoustic over the amplified, and the pastoral over the urban.

Schrimshaw works through correspondence between Schafer and Marshall McLuhan in order to interrogate the contradictions introduced into Schafer’s project of utopian soundscape design by this celebration of a pervasive electrical signal as a unifying device for communities, local and international. Schrimshaw’s study points out the sinister uses and side effects of unconscious auditory influences. At the same time, it suggests a recuperation of Schafer’s ‘prime unity’, in which passive acceptance of the side effects of infrastructure and engineering is replaced with active involvement in sound design, and the development of utopian soundscape practices that are not predicated on a rejection of the industrial and electrified world.

As always, Organised Sound publishes exceptional articles whose scope extends beyond the issue’s theme. This issue features the recent research of one of Organised Sound’s long-time board members, Jøran Rudi, on the Scandinavian computer-music pioneer Knut Wiggen (1927–2016). Wiggen saw non-intervallic electronic music as the necessary culmination of musical development and described the need for differing modes of listening that included emotional listening, intellectual listening and technical listening. His computer program MusicBox, which enabled users to transform experiences of sound into object-oriented building blocks that could be combined into musical compositions, can be seen as a precursor to current software platforms such as Max/MSP and PD. As Rudi explains, for Wiggen music was an intellectual construction, structured independently from the emergent qualities of sound itself. We hope that Rudi’s work marks just the beginning of scholarship taking up Wiggen’s compositional and technical contributions to electroacoustic studies.

6. CROSS FADE

Musicologists sometimes find more in common with historians studying the same time periods and geographical locations than with the musicians in their own departments. Yet the co-editors of this issue developed a close working relationship in the wake of discovering that our specialties, historical sound studies and computer-music composition respectively, share many foundational texts. During the course of late-night discussions after concerts, we found ourselves lamenting the fact that there are not many forums that explicitly engage the two streams of thought. We hope the articles collected here will inspire scholars of the past and composers of the present (and composing scholars and scholar-composers of the present and future), to converse and collaborate further.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to our brave authors, and to Organised Sound editor-in-chief Leigh Landy, for being willing to experiment with this thematic issue; to Perrin Meyer, of Meyer Sound Laboratories, for clarifying the collaborative dimensions of loudspeaker design; to Geoff Chew, Michael Scott Cuthbert, Lester Hu, Thomas Schmidt, Alexander Rehding, Jason Stoessel, for helping us puzzle through possible translations of Kircher’s Greek-Latin neologism ‘phonurgia’ and to Eric Bianchi (Fordham University) for proposing the most elegant of solutions to Kircher’s linguistic convolutions; to William Ashworth (University of Missouri-Kansas City and Linda Hall Library consultant for the History of Science) for anticipating that an LP with Kepler on the cover and an American Scientist article inside was just the thing a musicologist needed; to our colleague August Sheehy (Stony Brook University, Department of Music) for encouraging us to think about the ‘family resemblances’ between the harmonious universes of Stockhausen and Kepler; and to another colleague, Elyse Graham (Stony Brook University, Department of English), who helped us describe the circuitous linguistic pathways along which the new wor(l)ds – loud speaker, loud-speaker, loudspeaker – that lie at the heart of this issue came to be.