Family meals are an important social activity that may influence dietary intake and health. Many quantitative studies have examined family meals among children and adolescents, but few investigate the prevalence, predictors and outcomes of family meals among adults. The present analysis seeks to begin to fill that knowledge gap by analysing a large, contemporary US survey to examine the frequency of family meals among adults, the characteristics of adults who more or less often eat family meals, and the association between frequency of family meals and body weight.

Prevalence of family meals

Studies of the prevalence of family meals among children and adolescents report a wide variation of findings, partly because of measurement differences in survey question wording and dissimilarity of the samples. For example, some studies use questions that assess only dinner/supper family meals(Reference Sen1–Reference Taveras, Rifas-Shiman and Berkey3), while some consider all meals that could be family meals(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson4–Reference Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan7). Other investigations examine samples of very different ages. Overall, studies of family meals are more frequent among younger than older children and adolescents, with the majority of US young people eating family dinners together five or more days per week(Reference Sen1, Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson4, Reference Woodruff, Hanning and McGoldrick8, Reference Anderson and Whitaker9).

Studies of adult family meal prevalence in different nations report a prevalence of 46 % to 70 % of families eating a daily main meal together(Reference Warde and Martens10–Reference Holme12). In the USA, one study reported that 34 % of adults definitely agreed that ‘Our whole family eats together’(Reference Putnam13), while another noted that 75 % stated they ate together as a family at least five nights per week(Reference Herbst and Stanton14). Two analyses of family meal consumption by parents of adolescents found that over half of parents and about half of their adolescent children reported they ate family meals on four or five days per week(Reference Boutelle, Lytle and Murray5, Reference Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer and Story6). Overall, studies of the prevalence of family meal consumption reveal a wide range of findings for samples of children, adolescents and adults in several nations.

Predictors of family meals

Studies of the predictors of family meals have focused upon sociodemographic variables among children and adolescents. A review of Minnesota studies of family meals in adolescents(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson4) reported that girls, younger adolescents, Asian-Americans, those of higher socio-economic status and those whose mothers were unemployed reported they more frequently ate family meals. However, a review of research about family meals in the USA concluded that few characteristics of children were related to family meal participation(Reference McIntosh, Dean and Torres15). These findings about children and adolescents suggest that while gender, age, ethnicity, socio-economic status and work status may be predictors of the frequency of family meals, existing evidence is inconclusive.

Few analyses examine predictors of family meals among adults. In four Nordic nations(Reference Holme12) no gender differences existed in frequency of family meals, but adults who were older, less educated, not employed and in working class occupations more often ate family meals.

The extent to which sociodemographic variations in family meals is consistent or incongruous between adults and adolescents remains unclear. Furthermore, it is not clear how sociodemographic variables like marital status and parenthood that are not relevant to assess in studies of children and adolescents may be associated with frequency of adult family meals.

Body weight outcomes of family meals

A growing body of research has quantitatively analysed the relationships between frequency of family meals and body weight among children and adolescents. Most of these studies are cross-sectional surveys that have reported an inverse relationship between frequency of family meals and various measures of body weight(Reference Sen1, Reference Taveras, Rifas-Shiman and Berkey3, Reference Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan7, Reference Gable, Chang and Krull16–Reference Yuasa, Sei and Takeda18), although some studies have reported that the inverse relationship was limited to one gender(Reference Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan7, Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Eisenmann19, Reference Mikkila, Lahti-Koski and Pietinen20), ethnic group(Reference Rollins, Belue and Francis21) or social class category(Reference BeLue, Francis and Rollins22). In contrast, other cross-sectional studies have reported no association between family meal frequency and measures of body weight(Reference Woodruff, Hanning and McGoldrick8, Reference Utter, Scragg and Schaaf23–Reference Wurback, Zellner and Kromeyer-Hauschild27) or a direct association in some subgroups(Reference BeLue, Francis and Rollins22). A smaller number of longitudinal studies have examined frequency of family meals and change in body weight in children and adolescents over periods that ranged from 1 to 5 years, and have reported inverse associations(Reference Sen1, Reference Gable and Lutz24, Reference Price, Day and Yorgason28) or no significant associations(Reference Taveras, Rifas-Shiman and Berkey3, Reference Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan7).

Few studies provide quantitative data about how family meals are related to body weight among adults; those that do suggest that the association may be different for adults and young people. For example, a survey of students reported that eating fast food for family meals was not significantly associated with body weight for those adolescents, but more frequent fast food for family meals was related with higher body weight for their parents(Reference Boutelle, Fulkerson and Neumark-Sztainer29).

The need for research about adult family meals and body weight

Almost all existing quantitative studies of family meals and body weight sampled only children and adolescents, and sometimes their parents. However, findings drawn only from young people are limited in several ways, including: (i) representativeness of samples focusing on children and adolescents; (ii) divergence between young people and adults in experiencing and reporting about family meals; and (iii) differential effects of family meals on young people and adults.

The representativeness of child and adolescent samples is limited because they include only a portion of all families. The 2000 US Census found that households included 26 % with one individual living alone, 21 % with two spouses with no children, 27 % with two parents with children, 10 % with one parent with children, 3 % with unmarried partners with no children and 13 % other configurations(Reference Hobbs30). Many families include only adults with no children in the household as childless couples or those whose children have grown and left home. The prevalence, predictors and outcomes of family meals for adults without children may differ from those of households that include children(Reference Putnam13).

Divergence in family meal participation, experience and interpretation may occur between young people and adults. Compared with their parents, children and adolescents in the same household report eating fewer family meals, think family meals are less important, and are less sensitive to problems in scheduling family meals(Reference Boutelle, Lytle and Murray5, Reference Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer and Story6). Adolescents often have educational, extracurricular, employment and social involvements that prevent them from eating family meals, even when the parents and other family members eat together.

Differential effects of family meals may occur when joint meals provide benefits to young people that may not be beneficial and may even be disadvantageous for adults. Understanding family meals among many age categories, including adults, is important because family meals involve all members of the family. A suggestive example of such differential effects was seen in a study that found no association of frequency of family meals with adolescents’ weights, but higher weights among parents eating some types of family meals(Reference Boutelle, Fulkerson and Neumark-Sztainer29).

These and other limitations in existing research suggest that new studies of adult family meals are essential to more fully understand family meal prevalence, predictors and outcomes. Adult research is needed to complement and extend the substantial body of research in samples of children and adolescents.

We hypothesized that the prevalence of family meals among adults would be high, with most eating with other family members daily. We hypothesized that predictors of adult family meals would be congruent with Holme's(Reference Holme12) finding of more frequent family meals among older, less educated and unemployed adults, with no gender differences. We further hypothesized that whites more often eat family meals compared with black and Hispanic adults, who marry less frequently(Reference Cherlin31). We anticipated that married people more often eat family meals due to expectations about joint eating(Reference Bove, Sobal and Rauschenbach32) and that parents more often eat family meals based on child-rearing norms that prescribe joint eating(Reference McIntosh33). We hypothesized that, as with adolescents, the more often adults eat family meals the lower will be their body weights, and the less often they eat family meals the more likely that they will be overweight or obese.

Methods

Design and sample

Data for the present analysis were drawn from the Cornell National Social Survey (CNSS), an annual pilot-tested cross-sectional telephone survey conducted by the Survey Research Institute (SRI; Ithaca, NY, USA). The CNSS sample was collected in November and December of 2009 using random digit dialling to select households with listed and unlisted telephone numbers in the Continental USA provided by GENESYS Sampling Systems (Fort Washington, PA, USA). Within contacted households, the adult with the most recent birthday was sampled. Telephone interviews were conducted in English by trained interviewers using computer-assisted telephone interviewing software. The final sample size for the 2009 CNSS was 1000 completed interviews, with a cooperation rate (completed interviews/potential interviews) of 61 %(Reference Capagrossi and Miller34). The study was conducted in accordance with the Cornell University Institutional Review Board procedures about informed consent and data confidentiality.

Measures

Frequency of family meals was assessed using an item adapted for adults from the widely used question in the University of Minnesota EAT (Eating Among Teens) studies(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson4). The CNSS question asked: ‘In a typical week, how often do you eat a meal together with the family members who currently live with you? Never, 1 or 2 times, 3 or 4 times, 5 or 6 times, 7 times, over 7 times’. The inclusion of the ‘over 7 times per week’ category permitted family meals to be reported beyond dinner/supper meals. In addition to these six frequency categories, respondents also could reply that the question was not applicable because they were not living with family. The midpoint of each class interval (with >7 set to 9 meals) was used to construct a continuous measure of frequency of family meals per week.

Sociodemographic predictors were assessed using direct questions about the respondents’ gender, age in years, ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, other/multiple), marital status (married or not), presence of children under 18 years of age in the household (present or not), years of educational attainment and employment (employed full-time year-round or not). These dichotomous measures were used because of limited sample sizes available for finer categorization. Also, the CNSS data analysed here did not differentiate household categories in families without children present, i.e. those who were childless non-parents v. those who were parents whose children had grown and left home.

Body weight outcomes were assessed with three measures. Questions asked respondents to self-report their height and weight, which were used to construct a continuous measure of BMI (as kg/m2)(35). Self-reported height and weight may include reporting bias(Reference Gorber, Tremblay and Moher36), although one study reported high correlations between measured and self-reported weight (r = 0·97) and height (r = 0·93)(Reference Sobal, Hanson and Frongillo37). In the present analysis, under-reported weight would lead to underestimated associations between family meals and body weight. Dichotomous indicators of overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) were constructed from BMI(35) to examine both slightly heavier overweight individuals as well as much heavier obese individuals. Our sample had a slightly higher prevalence of overweight and obesity than national US data(Reference Flegal, Carroll and Ogden38).

Analysis

Missing values led to exclusion of thirty-four cases, resulting in an initial analytic sample of 966. An additional eighty-two cases reported having no family with whom to eat a family meal, and we excluded these cases from predictor and outcome analyses. We report significant main effects at P < 0·05 or less and interactions at P < 0·10(Reference Jaccard and Turrisi39).

Descriptive analyses examined the frequency of all variables to characterize the sample and provide the overall prevalence of the frequency of family meals. We compared respondents who reported they were not living with family members with whom they could eat family meals with all others, and differences were tested using χ 2 analysis and t tests.

Predictor analyses examined the association between frequency of family meals and seven sociodemographic characteristics in the CNSS data using multiple linear regression analysis.

Outcome analyses examined whether the frequency of family meals was associated with three measures of body weight. Multiple linear regression was used to model the frequency of family meals as a predictor of BMI adjusting for all sociodemographic variables; and separate multiple logistic regressions were used to model the frequency of family meals as a predictor of overweight and obesity adjusting for all sociodemographic variables. In addition to the main effects of each sociodemographic variable, a two-way interaction term between having children in the household and family meals also was included in the outcome models in order to test potential differences in the relationship between family meals and body weight in adults with and without children. These interaction analyses will help to consider the extent to which prior studies of family meals among children and adolescents can be generalized to families that have no children at home.

Results

Respondents without family members

Almost 9 % of this sample reported that they had no family members living in their household with whom to eat family meals. Compared with respondents with family, those without family with whom to share meals were significantly older and less likely to be married, to live with children or to be employed full-time year-round (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of respondents, body weight and prevalence of family meals, by having someone with whom to eat family meals: nationally representative US adult sample, 2009 Cornell National Social Survey

Significance: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

†Differences were tested using t tests and χ 2 analysis.

‡BMI data are available for 900 respondents.

Sample characteristics

In the remaining analytic sample (Table 1), slightly over half were women, the mean age was about 50 years, over three-quarters were white, most were married, under half had children in the household, on average they had education past secondary school, almost half were employed full-time year-round, most were overweight and a fifth were obese.

Prevalence of family meals

On average, respondents ate six family meals per week. The overall prevalence of family meals included 7 % of respondents reporting they never ate family meals, 21 % stating they ate family meals seven times per week, and 32 % more than seven times weekly (Table 1).

Predictors of family meals

Being married was a strong, direct predictor of frequency of family meals, with married respondents eating about two more family meals per week than unmarried respondents (+1·99, P < 0·01; Table 2). Full-time, year-round employment was a significant inverse predictor of family meals (−0·65, P < 0·01). Other sociodemographic variables were not significantly associated with family meal frequency.

Table 2 Multivariate model of demographic predictors of frequency of family meals: nationally representative US adult sample, 2009 Cornell National Social Survey

Significance: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

†The statistical significance of regression coefficients was examined using t tests.

‡White, non-Hispanic is the reference group.

Outcomes of family meals

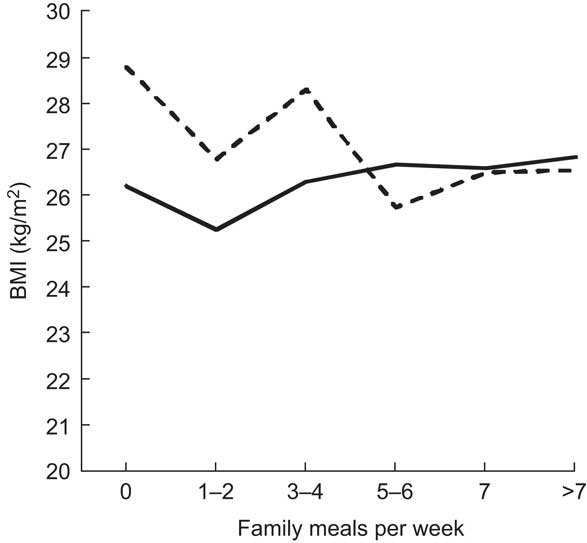

The frequency of family meals was not significantly associated with BMI, overweight or obesity in multivariate linear and logistic regression analysis adjusting for sociodemographic variables (Table 3). However, the interaction term between family meals and children in the household was associated with BMI (P < 0·10). In this model, adults in households with children had marginally higher BMI than adults in childless households (+1·72, P < 0·10), but more frequent family meals in this group were associated with lower BMI compared with households without children, where family meals were not associated with BMI (Fig. 1).

Table 3 Multivariate model of body weight by frequency of family meals and demographic characteristics, and the interaction between having any children at home and frequency of family meals: nationally representative US adult sample, 2009 Cornell National Social Survey

Significance: (*)P < 0·10, *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

†The statistical significance of linear regression coefficients was examined using t tests, and of logistic regression coefficients using Wald statistics.

‡White, non-Hispanic is the reference group.

Fig. 1 Regression-adjusted mean BMI by family meals per week for adults in households with (— — —) and without (——) children: nationally representative US adult sample, 2009 Cornell National Social Survey. Regression adjustment included gender, age, race, married, years of education and full-time, year-round employment

Discussion

The present study is unique as one of the first analyses that focus on family meals and body weight among a large representative sample of US adults, when most prior studies of family meals have focused on children and adolescents. While there were some similarities between these findings about adult family meals and studies of adolescents, several differences also existed.

A minority of this sample reported that they had no family members to eat with and therefore could not eat family meals. Sociodemographically, these individuals were older and more likely to be unmarried, not have children at home and not be employed full-time year-round. In studying family meals, it is important to recognize that some people do not have family members in their household and therefore cannot eat family meals as defined here; they should be excluded from family meal analyses so that they are not confused with people who live with family members but do not eat with them.

We found that the majority of adults (53 %) reported eating family meals seven or more times per week, and 72 % five or more times per week. These data provide a current national estimate of the frequency of family meals among adults in the USA and are consistent with studies in more limited US samples(Reference Putnam13, Reference Herbst and Stanton14).

Our estimates revealed more frequent family meals than have studies of adults in other nations(Reference Warde and Martens10–Reference Holme12) and most studies of adolescents(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson4). Differences in the prevalence of family meals may have occurred because of methodological variations, including differences in samples from different places and cultures, variations in sampling procedures, disparities in the questions used to assess family meals, and our exclusion of respondents who did not have family members with whom they could eat from our analytic samples. The higher prevalence of family meals among adults did not appear to occur because adult-only households more frequently ate family meals, because we found that the presence of children in the household was not a significant predictor of the frequency of family meals. Differences between adolescent and adult reporting of family meals may have occurred because adults better remember family meals, have a broader definition of family meals, are more committed to eating family meals than younger people, and place a higher priority on family meals than do adolescents who may skip family meals more often than adults(Reference Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer and Story6).

The findings about the sociodemographic predictors of family meals revealed that being married and not being employed full-time year-round were significantly associated with more frequent family meals in adults. Married individuals may eat more frequent family meals because they share joint households and a partnership where eating together is a marital ideal(Reference Bove, Sobal and Rauschenbach32). Individuals who are employed full-time year-round may eat family meals less frequently because of time demands of work and commuting, compared with part-time and seasonal workers, unemployed, retired and disabled individuals who have greater time available to them(Reference Jabs and Devine40). This finding of an inverse association between adult employment and frequency of family meals is congruent with some studies of adults(Reference Holme12) and adolescents(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson4). Overall, both marriage and employment provide social structures that may influence patterns of family meals among adults. These two variables do not apply directly to children and most adolescents and therefore were not highlighted in studies of younger individuals, but they do provide insights about social structures that influence family meals.

We found no overall association between frequency of family meals and any of the measures of body weight. This is congruent with a few studies of adolescents that reported no relationship(Reference Woodruff, Hanning and McGoldrick8, Reference Mamun, Lawlor and O'Callaghan25, Reference Wurback, Zellner and Kromeyer-Hauschild27), but incongruent with the majority of adolescent studies that reported an inverse relationship(Reference Sen1–Reference Taveras, Rifas-Shiman and Berkey3). However, a significant interaction in our analysis suggests that among adults there may be an inverse association between family meals and BMI in households with children, and no association between family meals and body weight for adults without children. In this model, adults in households with children were marginally heavier overall, but this was concentrated among adults with fewer family meals.

There are three potential explanations for the observed association between family meals and body weight only among adults with children: (i) family meals may influence the body weight of parents; (ii) parents’ body weight may influence the frequency of family meals; or (iii) both may be affected by other factors. It is important to consider all of these possible explanations because our cross-sectional data do not allow us to clearly establish the direction of causation.

First, frequency of family meals may influence parental body weight by encouraging parents to engage in social control over their own and their children's eating(Reference Umberson41). Eating as a family with children present may promote parental modelling of healthy food intake for children(Reference Bove, Sobal and Rauschenbach32) that moderates and minimizes food intake in an effort to promote a healthy meal environment, which influences the weight of the child and the parents. Family meals may also physiologically influence the body weight of parents by slowing their rate of eating(Reference Kokkinos, Roux and Alexiadou42).

Second, the body weight of parents may influence the frequency of family meals if heavier parents prepare fewer family meals. Sociologically, this might occur if heavier parents do not desire to serve as models of eating behaviour for their children, if they eat foods that they consider inappropriate for children, or if they engage in dieting or overeating behaviours that are incompatible with family meals. Also, if heavier parents are trying to lose weight, they may promote fewer family meals in order to avoid engaging in food shopping and preparation which is associated with additional food intake and higher body weights(Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg43).

Third, frequency of family meals and body weight may both be caused by other psychological, social, economic and cultural factors. For example, complex schedules, conflicting food preferences or family discord may lead to parental stress. Stress, in turn, may lead both to less frequent family meals and weight gain. Similarly, parents who generally conform more loosely to social norms may not participate in the ritual of family eating and also may have less desire to maintain a healthy body weight(Reference Block, Zaslavsky and Ding44).

While some prior studies had suggested unhealthy impacts of some types of family meals on parents’ weights(Reference Boutelle, Fulkerson and Neumark-Sztainer29), our findings suggest that, overall, family meals are associated with slightly lower body weights for parents. However, the CNSS data did not assess either food settings or food sourcing for family meals. Considering food settings like family meals at home, at the homes of others and at restaurants may help to understand these inconsistent findings. Food sourcing, like whether the food for family meals was cooked at home, prepared in a restaurant or had other origins, may also offer additional insight about family meals and body weight(Reference McIntosh, Kubena and Tolle45).

There are several limitations to the present study which deserve special note. While the sample was sizeable and representative of the USA, it was not sufficiently large to conduct separate stratified analysis of sub-populations like ethnic minorities. Cultural differences in family meals and associations with body weight may be particularly important to understand in the targeting of interventions which promote healthy eating or attempt to facilitate body-weight management. Measurement limitations include potential self-report biases, particularly socially desirable responses to questions about family meals and body weight. Under-reporting of weight(Reference Gorber, Tremblay and Moher36) would be expected to underestimate the relationships observed in the present analysis.

These findings have several implications and applications. They provide novel large-scale survey data about family meals and body weight among a broad cross-section of adults in the USA. Most adults report eating family meals daily, which is more often than adolescents report eating family meals. Marriage is associated with more frequent family meals among adults and full-time year-round employment is related to fewer family meals. Family meals are only marginally associated with body weight among adults living with children and not associated among adults not living with children. Our results are important to consider in counselling, educational, programme and policy decisions about providing and promoting family meals. Future studies about family meals would benefit from broader sampling of adults and young people, larger samples which contain sufficient numbers of respondents from diverse populations and settings to facilitate subgroup analysis, assessment of multiple members of the same households, and consideration of both nuclear and extended family meals. Further, while the present investigation focused on body weight as one potential outcome of family meals, future work should examine other health, psychological and social outcomes(Reference Story and Neumark-Sztainer46) which may be associated with family meals.

Acknowledgements

The research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector. The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this study. J.S. and K.H. participated in design of the study and writing the manuscript, and K.H. conducted the data analysis.