In the last two decades a growing literature has shown how central banking during the classical gold standard was a very active exercise, in conflict with the established view of banks of issue during this period having the mere task of converting banknotes into gold and vice versa. The well-documented case of Belgium (Ugolini Reference UGOLINI, Ögren and Øksendal2012a, Reference UGOLINI2012b) has paved the way for comparative studies showing, for instance, that central banks in core countries actively sterilised the impact of international shocks deriving from the exogenous rise of the British discount rate (Bazot et al. Reference BAZOT, BORDO and MONNET2016; Bazot et al. Reference BAZOT, MONNET and MORYS2022). At the periphery this policy of resistance to exogenous shocks was run with less effectiveness, yet studies on Portugal, Scandinavia and Austria have shown how central banks, in general, pursued strong policies of direct intervention aimed at stabilising the exchange rate (Reis Reference REIS2007; Jobst Reference JOBST2009; Ögren Reference ÖGREN, Ögren and Øksendal2012; Øksendal Reference ØKSENDAL, Ögren and Øksendal2012). Well aware that, in the periphery, variations of the discount rate were meant to be detrimental to commerce but to have a much lower positive effect on the exchange rate than in core countries, central banks decided to make wide recourse to alternative devices, usually based on the use of foreign exchange reserves. In fact, interventions in monetary and financial markets, both at home and abroad, represented more the rule than the exception; as noticed in the case of Norway, ‘the core of monetary policy was not to play along, rather, to avoid having to dance to the tunes of “the rules”’ (Øksendal Reference ØKSENDAL, Ögren and Øksendal2012, p. 37).

In general terms, it has been claimed that the same applied to Italy too; according to Bonelli and Cerrito (Reference BONELLI and CERRITO1999), for instance, the development of central banking in Italy since the early 1890s was the result ‘not of the adherence to the rules of the gold standard … rather of their failure’ (p. 289; author's translation). Despite such strong statements, in fact, little is known of the extent and of the specific types of direct market interventions put in place in the attempt to stabilise the exchange rate. In contrast with the abundance of the macroeconomic literature on the topic (Fratianni and Spinelli Reference FRATIANNI and SPINELLI1997; Tattara and Volpe Reference TATTARA, VOLPE, Marcuzzo, Officier and Rosselli1997; Tattara Reference TATTARA2003), specific and detailed micro studies of the exchange rate policies conducted by the Italian banks of issue are de facto non-existent, while a handful of publications treat the topic only as part of wider subjects. Among these, Spinelli and Trecroci (Reference SPINELLI, TRECROCI, Fratianni, Muscatelli, Spinelli and Trecroci2012) analysed discount rate policies during the pre-World War I period, but they struggled to establish a clear direction of causality between the discount rate and the exchange rate. Cesarano et al. (Reference CESARANO, CIFARELLI and TONIOLO2012) focused on the relation between exchange rate stability and the amount of international reserves held by the Banca d'Italia (henceforth BdI) but their analysis, apart from a quick mention of the 1907 crisis, has a macroeconomic perspective. De Cecco (Reference De Cecco1990), on the other hand, looked at the role played by the so-called gold devices and at direct interventions performed by Italian banks of issue – both the BdI and its predecessor, the Banca Nazionale nel Regno (henceforth BN) – but his analysis is limited to a section of a book's introduction and leaves most aspects just sketched. The most detailed micro studies of central banking in Italy between 1893 and World War I are those by Bonelli and Cerrito (Bonelli Reference BONELLI1991; Bonellli and Cerrito Reference BONELLI and CERRITO1999, Reference BONELLI and CERRITO2000), which provide key information on various institutional aspects of the operations performed by the BdI, but dedicate little space to the specific analysis of the exchange rate policy.

In the framework of the renewed interest in the actual nature and functioning of central banking during the classical gold-standard era, the lack of knowledge in the Italian case represents a significant gap in the historiography. In fact given, as the article will show, that Italian authorities engaged with different markets and a variety of devices, it also contributes to a more specific recent theme emerging in this literature, namely the determination and choice of the market(s) for central bank interventions (Jobst and Ugolini Reference JOBST, UGOLINI, Bordo, Eitrheim, Flandreau and Qvigstad2016).

The article is structured as follows: Section I looks at the evolution of the Italian exchange rate over the period under study. Sections II and III analyse the features (Section II) and effectiveness (Section III) of the interventions performed in the early 1880s. Sections IV to VI focus on specific subperiods, such as the difficult phase of the late 1880s–90s (Section IV), the transition and short-term crises around the turn of the century (Sections V), and the time of stability since 1905 (Section VI). Section VII provides some concluding remarks.

I

Before addressing the key issues of this article, an analysis of the pattern of the lira exchange rate is in order; given the depth and strength of commercial and financial links between the two countries, the price in lire of the fully convertible French franc is the most suitable measure to look at. As in the literature the period 1880–1913 is usually divided according to the prevalent exchange rate regime (Cesarano et al. Reference CESARANO, CIFARELLI and TONIOLO2012; Bazot et al. Reference BAZOT, MONNET and MORYS2022), we present the dataFootnote 1 desegregated by subperiods, as this also helps better contextualise the specific cases of intervention analysed in the article.

The first phase (1883–6)Footnote 2 can be defined as the era of the de jure and actual adherence to the gold standard: following the return to convertibility in 1883, the exchange rate stabilised around parity (100 lire per 100 francs), remaining below the gold export point of 100.5 (Ferraris Reference FERRARIS1901) until the end of 1886 (Figure 1a). During this period, variations (Figure 1b) were also limited in numbers and in size, within a band of about 0.2 per cent. Exceptions can be noted in January 1884 (when, despite the size of the variation, the exchange rate nonetheless remained below par), in October 1884 (with the exchange rate above par but below the gold export point), and May 1885 with the exchange rate above the upper gold point.

Figure 1a. Monthly exchange rate lira–French franc (lire per franc), January 1883 – December 1886

Source: see text, footnote 4.

Figure 1b. Monthly percentage variation of the exchange rate, January 1883 – December 1886

Source: see text, footnote 4.

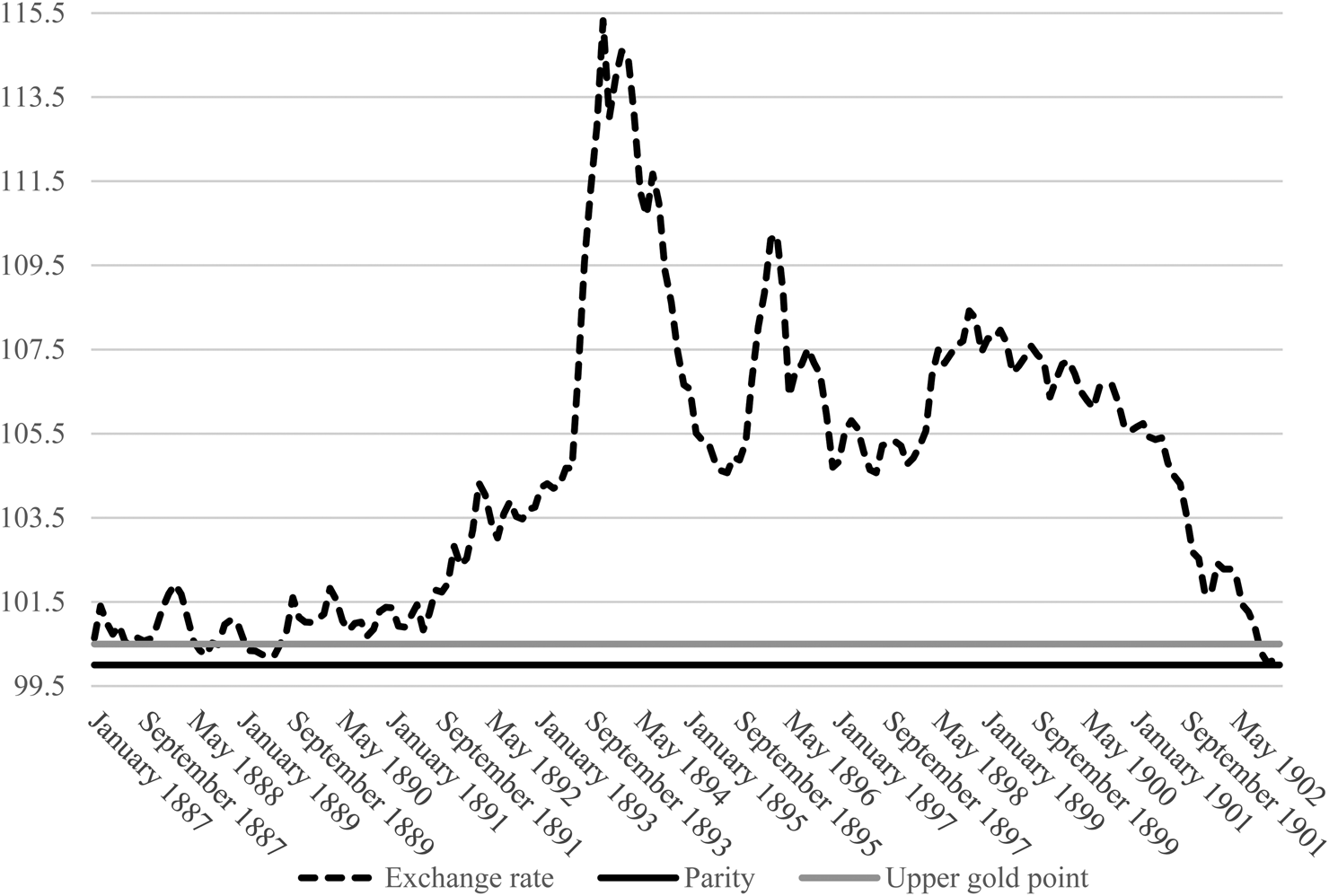

In the second period (1887–1902) the lira was de facto inconvertible into metal, despite the de jure adherence to the gold standard till the end of 1893. This phase can therefore be described as a period of floating exchange rate, and appears to be punctuated by episodes of sudden depreciations, such as in November 1891, and by an open and long-lasting crisis between 1893 and 1898. With a few limited exceptions at the beginning of the period, exchange rates never returned to below the upper gold point and for some years the premium over gold reached values even above 10 per cent of the parity (Figure 2a). Variations were frequent and deep too, with the most extreme reaching an order of magnitude (2.5 per cent) more than ten times those of the previous phase (Figure 2b).

Figure 2a. Monthly exchange rate lira–French franc (lire per franc), January 1887 – December 1902

Source: see text, footnote 4.

Figure 2b. Monthly percentage variation of the exchange rate, January 1887 – December 1903

Source: see text, footnote 4.

Towards the end of 1902 the exchange rate again reached par.Footnote 3 This was the beginning of a phase of de facto ‘shadowing’ of the gold standard (but not de jure adherence) which was pursued until the eve of World War I, although since September 1911 the exchange rate never returned below what would have been the upper gold pointFootnote 4 (Figure 3a). During the period up to 1909 the exchange rate remained very stable, with fluctuations contained in a band similar to that of the early 1880s. In this scenario of high stability, February 1904 stands out as a remarkable exception.

Figure 3a. Monthly exchange rate lira–French franc (lire per franc), January 1903 – December 1913

Source: see text, footnote 4

Figure 3b. Monthly percentage variation of the exchange rate, January 1903 – December 1913

Source: see text, footnote 4.

The picture presented above reveals cases of short-term depreciations, lasting in general one or two months, surfacing independently from the overall trends. The identification of these episodes, and their possible definition as ‘crises’, is central to the analysis of this article focusing precisely on the reactions to these circumstances. Just because of the general conditions in which these episodes took place, the ‘crisis’ attribute cannot be associated with a specific given degree of depreciation; in different subperiods similar fluctuations were or were not perceived as crises to react to. As the advice to act upon a crisis originated from the Treasury, its attitude towards different degrees of devaluation can be used as a guide to identify truly critical moments. During the period 1883–6 banks of issue were pressured by the Treasury to intervene anytime the exchange rate passed par with the French franc. For instance, between October 1884 and March 1885 the BN was asked to intervene in connection with exchange rate levels which were never above 100.35. In line with standard attitudes of the time, however, actual crises were only identified with levels of the exchange rate above the gold export point, such as in April–May 1885. The perspective changed after 1888 when the agio became a permanent feature of the Italian exchange rate and the Treasury took a more ‘relaxed’ attitude. Nonetheless, exceptional peaks were seen with concern and in November 1891, in conjunction with the crisis on the French stock market, the BN was again pressured to act. Up until the return to the de facto adherence to the gold standard towards the end of 1902, this remains the last documented episode of a request to intervene in the exchange rate market. In fact, since 1892 the very definition of short-term currency crisis disappeared in a context of extreme exchange rate volatility and the abandonment of the de facto (and then de jure too) adherence to the gold standard. In this situation, the very exchange rate targets become more and more elusive, besides some scattered reference to the value of 110 as a kind of ‘psychological’ resistance point. After the period of the floating exchange rate, during the ‘shadowing’ phase exchange rate targets (hence definitions of exchange rate ‘crisis’) returned to levels comparable to those of the early 1880s. Again, values above parity were regarded with concern and exchange rates above the gold export point as proper crises. In this context, the episode of January–February 1904 is emblematic. Interestingly, despite the international tensions visible in all markets, in November 1907 there was no exchange rate ‘crisis’ as such. This anomaly remains of interest for what it can nonetheless reveal about exchange rate policies and interventions.

II

The pattern of the lira exchange rate shows how episodes of short-term depreciation surfaced from the very beginning of the country's return to the gold standard. We argued that whether or not these fluctuations were considered as threatening and deserving direct intervention was usually not a decision made by the ‘central bank’; rather, banks of issue responded to the advice provided by the Treasury. Nonetheless, once asked to intervene, banks could decide which specific devices to use and in which markets to operate. The most immediate choice to be made was between manoeuvring the discount rate and implementing direct interventions in the exchange rate market. In the Italian context, the latter led to a further decision as to whether to act on the bonds or in the bills market.

At the beginning of the 1880s, the BN director Giacomo Grillo showed substantial ‘theoretical’ trust in the use of the discount rate to mitigate gold outflows, and on a few occasions this device was used with this explicit intent.Footnote 5 In practice, however, Grillo was aware that the possibility allowed by the Treasury to the banks of issue to discount bills also at a rate below the official one undermined the effectiveness of this device both in addressing as well as in preventing exchange rate fluctuations. In October 1884, for instance, Grillo drew the Treasury minister's attention to the fact that, in the opinion of the BN, the tensions visible on the exchange rate market had derived from a previous excess in this practice; this had led to a repatriation of high-quality commercial bills usually discounted abroad, and the consequent decline in the accumulation of hard currencies.Footnote 6

The awareness of the limitations in the effectiveness of discount rate variations might explain why the use of this policy was only part of a wider set of devices. During the same period another type of intervention consisted in the BN selling international bills of exchange owned in its portfolio or borrowing from lines of credit with international correspondents, to make hard currencies available to Italian traders in the form of cheques. This approach was a common device at the time, very similar to the one adopted by the Portuguese central bank (Reis Reference REIS2007). Discrete and effective, it was a much preferred alternative to gold export. Between October 1884 and March 1885, for instance, the BN committed about 43 m. to offer cheques payable in Paris and London in the main national financial centres, an operation judged as ‘often successful’.Footnote 7 In April 1885, the BN performed similar operations, committing 29 m. in the Swiss market to offset the sales of Italian bills, and selling in the domestic market 9 m. worth of cheques payable in Paris and London.

However, the bills market was only one of the contexts in which, according to the monetary authorities, the exchange rate was determined. The other market was the one for bonds, with the view that a decline of the price of Italian bonds (Rendita) floated in Paris vis-à-vis the price in Italy could trigger speculative movements able to influence the exchange rate. Two factors were behind the link between the bond prices and the exchange rate. Firstly, international bondholders could cash their coupons in gold and as institutional filters such as the so-called affidavit struggled to stop Italian investors too from engaging in these operations, a depreciation of the lira vis-à-vis gold (or gold-convertible currencies) led to an export of gold to deal with an increased demand for payment of coupons in metal, further exacerbating the original depreciation. Secondly, price differentials between the international and the domestic market could make it convenient to purchase bonds abroad (against payment in gold) and to sell them back in Italy. Considerations such as these made the BN spend about 6 m. in October 1884 and 25 m. in April of the following year to try and stabilise the Rendita price in Paris.

Although the solidarity between bond prices and the exchange rate was well known at the time, and the description of the mechanisms analysed above can be found quite frequently in contemporary articles and commentaries (Di Martino Reference DI MARTINO2022b), Italian central bankers seem to operate with a wide margin of uncertainty. In this phase interventions thus took place simultaneously on the bills as well as the bond market, with no precise indication of whether one was seen as more important than the other. Besides, when acting on the bond markets, the BN did not seem to have very precise targets in terms of prices to try and defend. In fact, decisions on where and how to intervene appear to be based mainly on idiosyncratic empirical considerations. In October 1884, for instance, in correspondence to the Treasury Grillo argued that the need to operate on the Paris bond market was made evident by the results of an enquiry made by the BN, which had identified the decline of bond prices among the reasons for the exchange rate depreciation. In April 1885, the intervention was officially motivated by the risk of a ‘disastrous liquidation’.

III

Also in light of these considerations, one relevant question about the strategies for intervention chosen by the BN in the early 1880s concerns the two interrelated aspects of their effectiveness and sustainability. To investigate these issues we need to venture into the analysis of three different aspects: the availability of resources to operate; the effect of direct intervention on market behaviour; and the overall effectiveness of the discount rate policy.

To analyse the first point, the key variable of interest would be the volume of forex reserves, the resources more suitable for direct market interventions. For the period up to 1894, however, it is impossible to derive a consistent series; as the legislation disallowed the (official) cumulation of forex assets, these were not reported separately in the annual or monthly balance sheets.Footnote 8 Neither did the management of the BN usually provide quantitative indications in internal reports.Footnote 9 The only available source is a private letterFootnote 10 in which Grillo argued that the level of forex reserves was about 21 m. at the end of 1884, and only an estimated 5 m. by the end of April 1885. Although patchy, this indication makes clear that the operations on the bills market performed between October 1884 and March 1885 had exhausted the amount of available forex reserves, which appears not to have been built up again. In fact, from the 1887 BN annual report to the shareholders it is possible to reconstruct the two main reasons why the bank did not commit itself to piling up a robust stock of forex assets: firstly, a general lack of availability of good-quality international bills in the Italian market; secondly, as the Italian legislation did not allow forex reserves to be included in statutory ones, an investment in foreign bills would have reduced the volume of funds for operations in the domestic market, creating a potential liquidity shortage.Footnote 11

Whatever the reasons for the limited amount of forex assets in the BN portfolio, the implication was that different resources had to be found for interventions in the bond market in October 1884 and May 1885, and for the other operations made in the same month. In October substantial help came from the Treasury, which lent the bank 6 m. worth of foreign assets.Footnote 12 In the following April, however, operations could only be made by exporting metal. Figure 4 shows the pattern of the amount of metallic reserves held by the BN in the months immediately before and after the two interventions in October 1884 and May 1885.

Figure 4. BN metallic reserves, million lire (monthly frequency), September 1884 –August 1885

Source: De Mattia (Reference DE MATTIA1967), table 19.

Data show how the decline in metallic reserves was already noticeable in October (about 10 m.) despite the financial support from the Treasury. In April, however, the loss of reserves was deeper, with a decrease of about 26 m. In fact, the actual decline consisted of about double this amount, but the bank managed to refill the metallic reserves alienating about 27 m. worth of biglietti consorziali.Footnote 13

The analysis of the availability of resources to be used for direct intervention reveals that they were indeed limited; a more precise assessment of how limited, however, also requires looking at the other side of the coin, i.e. the effectiveness of such manoeuvres. A way to answer this question can be provided by measuring the strength of direct intervention in the bond market in changing the convenience of operations of arbitrage. As recalled in the previous section, the BN intervened in the bond market on the basis of the expected solidarity between bond prices and the exchange rate. However, we also know that, although aware of this mechanism, the BdI lacked a precise sense of the exact quantitative relation among these variables and of a clear price to target. Daily data on bond prices and exchange rates for October 1884 and April–May 1885 can be used to investigate this relation and the meaningfulness and effectiveness of direct interventions. According to Tattara (Reference TATTARA2002), perfect market integration led to equilibrium conditions between the price of Italian bonds in Paris and Rome when expressed in the same currency, and by taking into account a transaction cost of the arbitrage of about 0.5 per cent of the price of Rendita on the domestic market. If we take the changes in the international and national prices of Italian bonds as the independent variables (as assumed by contemporary observers), this implies that it was the exchange rate that had to vary to restore equilibrium. If the exchange rate depreciated below this level, this implies that other elements too impacted on this variable. Figures 5 plots for the two periods October 1884 (Figure 5a) and April–May 1885 (Figure 5b) the daily price of Italian bonds in both Rome and Paris, the actual exchange rate and the equilibrium rate, i.e. the one that would have made the difference between the domestic price of the Italian bond (-0.5 per cent transaction costs) and the international one (in lire) equal to zero.

Figure 5a. Italian public bonds price in Rome and Paris, actual exchange rate and equilibrium exchange rate (daily), October 1884

Source: Ministero delle Finanze, Annuario del Ministero delle Finanze, 1885.

Figure 5b. Italian public bonds price in Rome and Paris, actual exchange rate and equilibrium exchange rate (daily), 8 April – 20 May 1885

Source: Ministero delle Finanze, Annuario del Ministero delle Finanze, 1886.

As far as October 1884 is concerned, the first thing to notice is how the actual exchange rate tended to remain higher than the equilibrium rate, suggesting that a set of factors affected the pattern of this variable, and that the support to the Rendita in Paris could only partly solve the problem. In this context, the intervention by the BN, which took place in the days after 13 October, appears rather successful: after the lowest price of the 14th (corresponding to the highest level of the exchange rate), the price of Italian bonds increased, leading to a decline in the equilibrium and, although only to an extent, in the actual exchange rate too.

Compared to October 1884, the 1885 crisis was deeper with the exchange rate passing the gold export point. Also in this episode, instances can be noticed when gaps opened between the actual exchange rate and the equilibrium rate. At the beginning of the period and then again at the beginning of May, the actual rate was below the equilibrium rate, suggesting that the arbitrage process was not immediate. More often, however, the actual rate was higher, an indication that, likewise in October 1884, the differences between the prices of the Rendita in Italy and abroad could only partially explain the exchange rate devaluation. In this situation, as recalled in the previous section, the BN intervened largely to avoid deepening the crisis, not necessarily to restore the exchange rate at the previous levels. In this perspective the initial intervention performed on 16 April had a positive impact on the price of the Italian bonds in Paris and the equilibrium exchange rate. The pattern of the crisis, however, reveals the problem highlighted before, the inability to sustain this sort of intervention for long enough: in the face of the constant decline in the price of bonds from 18 April to the end of the month, the BN was de facto unable to act.

The last point about the effectiveness of the interventions concerns the use of the discount rate leverage. Indeed, as Figure 6 shows, the BN increased the official rate parallel to the development of direct interventions in exchange rate markets, an approach that reflected a degree of trust in this device.

Figure 6. BN official discount rate (monthly average), September 1884 – August 1885

Source: De Mattia (Reference DE MATTIA1967), table 20.

It was exactly the limited effectiveness of this manoeuvre in April 1885, however, that changed Grillo's view. In discussing the 1885 events a few years later, Grillo argued that Italy's peripheral position in the world of international finance made the rise of the discount rate useless in contrasting capital outflows.Footnote 14

IV

The chronology of interventions made in the early 1880s reveals a very fragile situation characterised by the scarcity of resources to operate in exchange rate markets, in particular the lack of sufficient foreign assets in the portfolio of the BN. Difficult as they were, however, interventions in the early to mid 1880s took place in a much better context than in the following decade and half. Since 1887, the definite exhaustion of foreign assets reserves in the BN balance sheet teamed up with the consequences of the break-up of the traditional political–military alliance with France, and the decision to gravitate instead towards the German sphere of influence. This decision contributed to alienating the sympathy for Italian bonds and bills in their main international market, while the support offered by German banks appeared timid and weak; as the director of the BN Grillo noticed in summer 1889, in case of crisis ‘we could only rely on our own strengths’.Footnote 15

In this blinkered scenario, the approach by the BN (and later the BdI) appeared to be inspired by two basic ideas. The first was the consolidation of the principle of the ineffectiveness of the use of the discount rate lever. The second was the definition of the bond market as the main centre of exchange rate tensions; most likely because of the sheer increase in the amount of Italian bonds quoted abroad,Footnote 16 the idea of the price of the Rendita abroad as the main engine of exchange rate fluctuation became uncontroversial in contemporary documents and publications.Footnote 17

The French market crisis of November 1891 offers a revealing documented example of how much the conditions around direct intervention in the exchange rate market had changed for the worse. As in the 1880s, the crisis took the standard form of a general scarcity of funds in the financial market and massive liquidation of foreign bills and bonds; among them, noticed the Italian Treasury minister, ‘the most mistreated were the ones of debtor countries’.Footnote 18 Figure 7 gives a sense of the degree of such depreciation plotting the weekly price of Italian public bonds on the French exchange market between the end of October and the beginning of December 1891.

Figure 7. Weekly average price of Italian public bonds in Paris (16 October – 11 December 1891)

Source: Il Sole.

If the crisis does not reveal, at first glance, a different nature vis-à-vis episodes such as the one of April 1885, what had changed dramatically was the ability to tackle it. The support by the new allies (a consortium of German banks) did not lead to any improvement in the price of Italian assets in the face of the still-negative attitude of other financial investors.Footnote 19 Squeezed between the harshness of the crisis, the weakness of German support, and the lack of foreign reserves, contrary to what happened in 1885, the BN this time explicitly surrendered in the awareness that an intervention in the market would have been a ‘useless venture’.Footnote 20 Again in contrast with the early 1880s, when the storm passed things only minimally improved; during the early 1890s, with the exchange rate consistently well above the gold export point, the difference between navigating medium-term trends and addressing short-term crisis blurred, leading to the need for a constant, painful yet relatively ineffective defence of the price of Italian bonds and of the exchange rate. With this aim, the Treasury decided to form a consortium, participated in by the banks of issue, with a twofold strategy. The first was to try and absorb foreign exchange bills in the Italian market and to re-sell them at a capped price to stop the speculators; the other was to restrict domestic credit to importers and instead use these resources to finance the purchase of public bonds abroad.Footnote 21 But – the Treasury Minister claimed – with 2 billion worth of Rendita floated abroad and the banks already weakened, the fight was tiring and the results meagre: it stopped the exchange rate reaching more than a 10 per cent depreciation, and the price of bonds abroad going below 80.Footnote 22 And the effort of trying to influence the international press, by ‘spending some thousands lire … to defend and let Paris know the truth about our Rendita and our economic and financial situation’, did not bring any better result.Footnote 23

If possible, things got even worse after 1893. In February, in a letter to the French correspondent Fournier, Grillo bitterly admitted: ‘I can see that, unfortunately, things there took a bad turn and I cannot get a great deal of consolation thinking about our situation, as things here are not going well either.’Footnote 24 In this scenario, Italian authorities could only resort to some desperate strategies – such as influencing the press – in an attempt to support the value of Rendita abroad. Even these stratagems, however, were quickly dropped due to their lack of effect.Footnote 25 For the remaining part of the decade, in fact no actual active intervention for the defence of the exchange rate was put in place.

V

Although the 1890s represented the hardest phase of interventions in exchange rate markets, during these years a key institutional reform paved the way for more effective operations: the possibility for the BdI to legally keep forex reserves. The reform allowed forex reserves to be used both as part of the statutory ones (i.e. reserves to be used to cover money supply) and as ‘free’ reserves as part of the bank's portfolio. While the former represented, mainly, a financial advantage for the bank and only indirectly helped to support the exchange rate,Footnote 26 the latter were conceived explicitly as the first line of defence against exchange rate depreciations: they could be accumulated when exchange rate variations made it convenient and, if needed, spent quickly and discreetly.Footnote 27 Initially, however, the 1893 Bank Act set the level of free forex reserves in a rigid way and limited it to a maximum of 6 m. lire. Well-informed players such as Stringher, the director of the BdI, quickly realised that the threshold was too low and, informally, often went above it.Footnote 28 Towards the end of November 1903 Stringher wrote to the Treasury demanding more elasticity in the management of foreign exchange reserves, for the first time making explicit reference to the defence of the exchange rate.Footnote 29 The ministry reply was supportive, yet rather conservative: the bank was asked to operate in this respect using the utmost prudence.Footnote 30 Maybe because of this recommendation, or simply because of a lack of time, by the time international financial instability manifested itself again between the end of January and the first week of February 1904, the BdI free forex reserves were only about 8 m.Footnote 31

In conjunction with growing tensions between Russia and Japan, the exchange rate – whose average had remained below par in December – reached the value of 100–100.05 during the first weeks of January.Footnote 32 The depreciation of the exchange rate, however limited, worried the Treasury, which put pressure on both the BdI and the Banca Commerciale Italiana (henceforth BCI) to ‘monitor and intervene’.Footnote 33 The reaction to the Treasury request did not produce any change in the discount rate: in fact the averageFootnote 34 monthly discount rate even declined mildly, passing from 4.69 in December to 4.66 in February. On the other hand, between 25 January and 6 February, the BdI and the BCI – which also offered logistical support in the actual running of the operations – reacted decisively by selling a total of more than 23 m. of foreign exchange bills in various Italian financial centres, while only marginal attention was paid to the bond prices abroad.Footnote 35 Stringher and Joel (the BCI director) appeared ‘rather satisfied’ with the outcome of their efforts,Footnote 36 having defended a brave target of 100.2–100.25, an exchange rate well below the upper gold point. An even more reassuring result when considering that the whole operation was run without any commitment of the metallic or statutory forex reserves, but only with the buffer offered by free forex reserves. High frequency (ten-day) data on the BdI reserves desegregated by typologies (Figure 8 below) reveal the stability of the former two types of reserves, and a contraction of the latter of about 6 m. since December 1903.

Figure 8. BdI reserves, million lire (ten-day frequency), 10 December 1903 – 30 April 1904

Source: Banca d'Italia, Situazioni decadali, 1904.

Despite this initial achievement, awareness quickly surfaced that the continuous success of the operation was meant to be conditional on international political contingencies, and that a worsening of the political tensions was destined to turn the manoeuvre into a failure.Footnote 37 The beginning of the following week saw the materialisation of such fears: on 8 February the Japanese fleet attacked the Russian base of Port Arthur and on the 10th Japan formalised the war declaration. Italian authorities had only to wait another day for old ghosts to reappear in the form of a crash of the bond prices in Paris; on 11 February the Italian Rendita – sold at 102.17 at the beginning (the 2nd) of the month, dropped to 99.95.Footnote 38 Two days later, commenting on these events, Stringher wondered bitterly whether ‘the roar of the Japanese artillery would not have called Italy back to reality’.Footnote 39

Despite the specific pressure on the bond prices, this second phase of the crisis saw the BdI (and the BCI) rethinking all possible options in terms of which markets to intervene in and types of devices to use, revealing how the exclusively narrow focus on the bond market, typical of the early 1890s–1902 period, had paved the way for a more pragmatic approach similar to that of the early 1880s. Joel, in particular, suggested that the focus should have been kept mainly on the domestic markets for bills, associating direct interventions with an increase of the minimum discount rateFootnote 40 applied by the BdI.Footnote 41 Although convinced of the centrality of the bills market, nonetheless Stringher insisted on operating first in the international bond market, not so much for the direct impact on the exchange, but rather for fear of a disastrous crash. Likewise in previous experiences in the 1890s, Stringher also reiterated his idea of the lack of effectiveness of an increase in the discount rate.Footnote 42 It did not take long, however, to understand that the real issue was not so much which market to intervene in, but rather how and with which resources. Faced with the estimated need to commit ‘in a few days … about 50 millions’ and the volume of free forex reserves reduced to a mere 4 m. by 10 February, the only viable and potentially effective solution appeared to be a direct intervention committing ‘various tens of millions of the gold stock-piled by the Bank [of Italy] and the Treasury during the period of exceptionally low exchange rate’.Footnote 43 In the end, confronted with differences of opinion with the Treasury about targeting Italian bonds abroad or the exchange rate in domestic markets, the minister's uneasiness about the use of gold to defend the bond prices, and the suggestion to resort, instead, to an international loan, the crisis simply lingered on for another ten days till, on 23 February, the BdI de facto abandoned the battlefield and renounced any further intervention.Footnote 44

VI

However limited in its length, the 1904 crisis showed that despite the institutional changes implemented in regard to forex reserves, the BdI was still poorly equipped to make effective interventions in the exchange rate market. Also as a result of this failure, the Treasury abandoned the previous prudent view towards the increase of free forex reserves whose monthly average during the following years spanned between 20 and 40 m. (Di Martino Reference DI MARTINO2022b).

The effectiveness of this approach was destined to face a potentially even more severe test than in 1904 as a consequence of the American financial crisis of the last month of 1907. This time, however, the lira exchange rate was only minimally affected: in October the exchange rate even marginally appreciated (from 98.83 to 99.73), and in November and December remained around nominal parity. Considering the extent and depth of the international crisis, this pattern appears puzzling, raising the question of whether the performance of the exchange rate might have been also due to successful interventions. In fact, on more than one occasion (firstly in the reports to the Consiglio Superiore, then in the annual report to the shareholders), Stringher reiterated the message that the exchange rate had simply remained tendentially favourable to Italy given the limited amount of international debts.Footnote 45 This rosy reconstruction of the event, however, is somehow contradicted by a press articleFootnote 46 published by the Treasury minister Luzzatti, who argued that 1907 was a record year for imports, in particular of steel. How was it possible – Luzzatti then wondered – that this happened without affecting that ‘infallible thermometer’ that is the exchange rate? According to the minister, the answer could not be found in migrants’ remittances (halved by the crisis), rather in the expenditure of the substantial buffer of forex assets to settle international debts. Although not via direct interventions, forex reserves thus proved a key element for the stability of the exchange rate. But was it the only role they played in the crisis? Luzzatti himself opened the door for a different interpretation, suggesting the existence of ‘unknown factors’. To inquire into the hypothesis that direct interventions in exchange rate markets might have been among those factors, a reconstruction of the policy during the central months of the crisis is in order.

In the final month of 1907, the BdI used a ‘Bagehot-style’ approach, expanding credit supply but, after having discarded this option up to October,Footnote 47 also pushing for an increase in the official discount rate and de facto stopping discounting below it (Figure 9).

Figure 9. BdI, monthly average discount rate, June 1907 – March 1908

Source: Bagliano and Di Martino (Reference BAGLIANO and Di MARTINO2022).

In order for credit expansion not to create negative expectations on the exchange rate, however, a parallel increase in the level of reserves was needed. Data suggest that this was the case (Figure 10).

Figure 10. BdI, reserves and domestic portfolio, million lire (ten-day frequency), 10 September 1907 – 10 January 1908

Source: Banca d'Italia, Situazioni decadali, 1907.

The balanced character of the credit expansion and the absence of negative expectations, however, do not rule out the possibility that the exchange rate stability might have also been due to direct interventions. Somehow, an indication that this might have been the case comes from a subtle indication in the 1907 annual report to the shareholders where Stringher suggested that the bank ‘could take advantage of the substantial availability of Italian foreign credits’.Footnote 48 As a matter of fact, Figure 10 above shows a sharp decline of free forex reserves in conjunction with the other operations. However, on the basis of some indications coming from the same report, Bonelli (Reference BONELLI1971, p. 136) had concluded that the decline of free forex assets was due to their conversion into metal to contribute to the expansion of statutory reserves in a phase when buying gold was difficult. Using ten-day frequency data we are in a position to ‘test’ this hypothesis. The main increase in metallic reserves took place between 30 September and 20 November, with a variation of about 106 m. Most of the increase was financed by a loan of 60 m. coming from the Treasury, but clearly the BdI had to find other means to finance this expansion. The contemporary decline by about 10 m. in the volume of the free forex reserves might therefore be entirely explained by this need, although we have no hard evidence that part of free forex reserves had not been used for market intervention.

In the end, it thus seems that in 1907 no direct intervention was implemented to support the exchange rate, whose stability can be explained by other factors. However, the growing level of free foreign assets, piled up over the years to fight possible tensions in the exchange rate market, proved nonetheless useful in contributing to this success in various ways.

VII

Little is known of how during the international gold standard the Italian central bank supported the exchange rate using direct interventions in domestic and international markets. This article sheds light on this issue by analysing various examples of these policies implemented from the early 1880s to the eve of World War I.

In general, interventions were activated in response to pressure coming from the Treasury and not by direct initiative of the banks. Nonetheless, they retained wide room for manoeuvre in terms of selecting the markets in which to operate and the devices to make use of. In the early 1880s, the BN used a wide combination of instruments (interventions in the bills and bonds market and increase in the discount rate), while in the period between 1887 and 1902 the attention was exclusively on the price of Italian public bonds in Paris. In the final phase of the period under study the BdI focused again on both markets, but discount rate increases appeared again only in 1907.

When activated, such as during the exchange rate crises of 1884–5 and 1904, the policy of direct intervention appeared initially successful, showing that monetary authorities were able to pinpoint the relevant markets and to influence them. However, the chronic scarcity of foreign assets in the banks’ portfolios drastically limited the viability of these operations, and hence their overall effectiveness when crises lingered for a few weeks. The structural problem of the scarcity of reserves to commit, due to institutional and legal constraints, thus appears as the actual issue that Italian central banks had to deal with, rather than the potential ability of these policies to support the exchange rate. After 1904 the institutional constraints had been relaxed, but the extent to which these changes might have solved the problem remains a matter of speculation, as no documented example of direct market intervention can be found after 1904. Certainly the wider availability of free forex reserves was part of the reasons behind the successful management of the 1907 international crisis, although it is likely that this was addressed without resorting to direct intervention in exchange rate markets. On the other hand, however, the depreciation of the lira visible towards the end of the period, despite the alleged use of foreign reserves to counteract it,Footnote 49 casts some shadow on the idea that, eventually, Italy had built a strong enough arsenal to fight the exchange rate war effectively.

Besides the assessment on the effectives of these policies, overall this article shows how the Italian case between 1880 and World War I supports the emerging picture of central banking during the classical gold standard years as a very articulated, sophisticated and active exercise. The constant commitment – and key role – of central banks to exchange rate stabilisation via direct interventions in markets, already analysed in a number of national case studies, is indeed confirmed for Italy too.