The French physiologist Claude Bernard (1813–1878) is not only one of the first to propose blind experiments to reduce bias(Reference Daston1) but also is credited with the discovery of glycogen in the liver, thus revealing the central role of this organ in the homeostatic regulation of blood glucose concentrations (or milieu intérieur)(Reference Young2, Reference Bernard3). Bernard originally intended to study the metabolism of all types of foods, choosing to start with the putatively simple metabolism of sugars. The complexities of sugar metabolism led Bernard to focus on this area for more than 30 years and, in understated fashion, he described this systematic and meticulous undertaking as ‘research which has not been wholly sterile’(Reference Bernard4). During this time, he found that the portal vein of dogs (the major blood supply to the liver) has little to no glucose, whereas the hepatic vein leaving the liver carries substantial quantities of glucose. This led Bernard to conclude that the liver is a potential source of sugar. This capacity of the liver to supply glucose to the systemic circulation is important when dietary carbohydrate intake is insufficient to meet the carbohydrate demands of tissues such as the brain and muscles. Therefore, during fasting, exercise or consumption of low-carbohydrate diets, the liver can supply glucose for peripheral tissues. Glucose produced by the liver is derived from two sources: the breakdown of stored glycogen (i.e. glycogenolysis), and the de novo production of new glucose from precursors such as lactate, glycerol, pyruvate, glucogenic amino acids, fructose and galactose (i.e. gluconeogenesis)(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts5). The liver is the largest glycogen store in human subjects that can be hydrolysed and release glucose into the circulation to sustain blood glucose concentrations, and is also the tissue with the greatest capacity for gluconeogenesis. Therefore, the ability for the liver to supply glucose from both glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis has important consequences for maintaining metabolic control during exercise, and especially when dietary carbohydrate intake is restricted.

The liver also plays a central role in the postprandial metabolism of carbohydrates. Following intestinal absorption, the liver is one of the first tissues exposed to ingested carbohydrate. Whilst the intestine (and kidneys) can also metabolise some dietary sugar(Reference Jang, Hui and Lu6) and undertake gluconeogenesis(Reference Mutel, Gautier-Stein and Abdul-Wahed7), these are quantitatively less important than hepatic metabolism, at least in human subjects(Reference Gonzalez and Betts8). Various types of sugars are distinctly metabolised by the liver, with potential implications for human health and performance(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9, Reference Tappy and Lê10). Accordingly, the aim of this narrative review is to describe the hepatic metabolism of dietary sugars at rest and during exercise, whilst considering potential implications for human health and (endurance) exercise performance.

Dietary sugars

Common sugars in the human diet include the monosaccharides: glucose, fructose and galactose; and the disaccharides: sucrose (fructose–glucose), lactose (galactose–glucose) and maltose (glucose–glucose)(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9). Dietary sugars can be consumed from a variety of food sources, which can influence resultant health effects. The WHO classifies sugars into those which are intrinsic (e.g. incorporated within the structure of intact fruit and vegetables or lactose/galactose from milk) v. free sugars(11). Free sugars are defined by the WHO as monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods and beverages by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, along with sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates. This classification system is useful for distinguishing between food sources of sugar that are energy dense (i.e. free sugars) and thus may contribute to weight gain(11, 12). However, this classification system does not specifically distinguish between ingestion of glucose-containing sugars and fructose- or galactose-containing sugars in relation to health, nor does it consider the physical activity status of the individual. This is interesting considering the fundamental differences in the intestinal absorption and hepatic metabolism of glucose, fructose and galactose, and how this metabolism is altered during exercise(Reference Gonzalez and Betts8–Reference Tappy and Lê10).

Before describing the hepatic metabolism of carbohydrates and sugars, it is important to clarify two points. First, the hydrolysis of glucose polymers such as maltodextrin and starch are typically not rate-limiting to intestinal absorption(Reference Hawley, Dennis and Laidler13), and therefore (at least with regard to hepatic metabolism) free glucose, maltose, maltodextrin and starch can all be considered physiologically similar stimuli. Secondly, in typical human diets, free glucose is rarely consumed alone, but rather is usually consumed alongside fructose or lactose, or is consumed in polymer (non-sugar) form, such as maltodextrin and starch. Accordingly, whilst this review will refer to the specific types of sugars utilised in studies (e.g. glucose only v. fructose–glucose mixtures), it can be viewed that a non-fructose or non-galactose condition (such as glucose or maltodextrin ingestion) is physiologically representative of non-sugar intake (i.e. maltodextrin, starch, etc.), whereas fructose–glucose and galactose–glucose co-ingestion represent the physiological responses to typical sugar intake.

Hepatic metabolism of sugars at rest

Glucose and galactose are primarily absorbed across the intestinal lumen via the transport protein sodium-dependent GLUT2(Reference Daniel and Zietek14), whereas fructose is primarily absorbed via GLUT5(Reference Daniel and Zietek14). Once absorbed, these sugars are then metabolised very differently. Glucose is preferentially metabolised by extra-splanchnic tissues such as skeletal muscle, the brain and cardiac muscle(Reference Kelley, Mitrakou and Marsh15, Reference Ferrannini, Bjorkman and Reichard16), whilst fructose and galactose are primarily metabolised by the liver and to a lesser extent small bowel enterocytes and proximal renal tubules(Reference Tappy and Lê10, Reference Williams17). Peripheral tissues such as muscle are therefore only exposed to relatively small amounts of fructose and galactose(Reference Ercan, Nuttall and Gannon18, Reference Chong, Fielding and Frayn19).

Compared with galactose, the metabolic fate of fructose is relatively well characterised. At rest, the liver rapidly takes up and metabolises fructose into fructose-1-phosphate (P) via fructokinase (K m for fructose: about 0·5 mm and V max estimated at about 3 mm/min per g human liver)(Reference Heinz, Lamprecht and Kirsch20–Reference Hers and Kusaka22). Fructose-1-P is then metabolised into triose-P (C3 substrates) via aldolase B(Reference Mayes23). At rest, the majority of fructose-derived triose-P is converted via gluconeogenesis into glucose (about 50 %) and glycogen (about 15–25 %), but some of triose-P can be metabolised into pyruvate, then either oxidised within the liver or converted into lactate (about 25 %), which enters the systemic circulation and can increase blood lactate concentrations(Reference Tappy and Lê10, Reference Björkman, Gunnarsson and Hagström24). One other fate of ingested fructose is the conversion into fatty acids via the process known as de novo lipogenesis(Reference Bar-On and Stein25). It has been suggested that lactate is the primary precursor to hepatic de novo lipogenesis with fructose intake(Reference Carmona and Freedland26), but the proportion of fructose that is ultimately converted into lipid is estimated at <1 % and therefore represents a quantitatively minor pathway of disposal(Reference Chong, Fielding and Frayn19). Nevertheless, the effects of ingested fructose on de novo lipogenesis may still be important for metabolic health(Reference Sanders, Acharjee and Walker27).

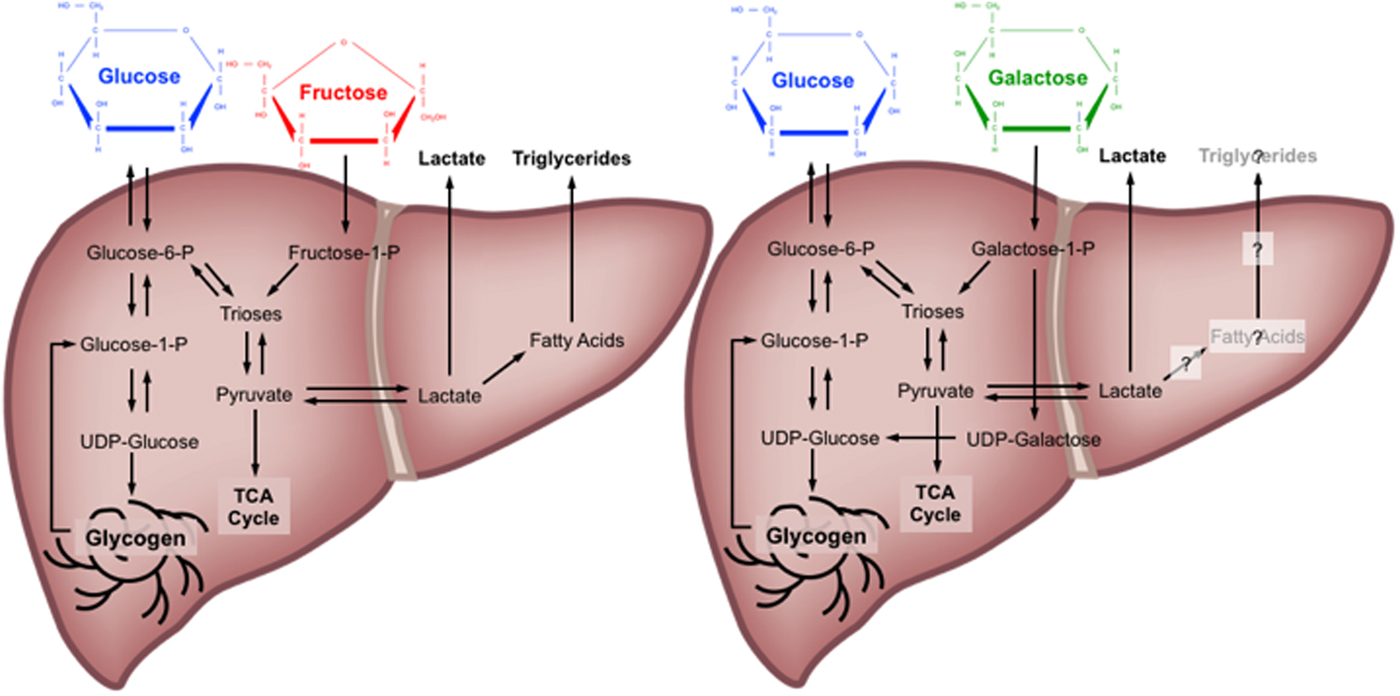

Quantitative estimates of the metabolic fate of galactose in human subjects are scarce. It has been suggested that the primary pathway for human galactose metabolism is the Leloir pathway, the enzymes of which show highest activity in the liver(Reference Williams17). This pathway involves four main steps: (1) phosphorylation of galactose by galactokinase (K m for galactose: about 0·9 mm and V max estimated at about 1·4 mm/min per g human liver(Reference Timson and Reece28, Reference Sørensen, Mikkelsen and Frisch29)) to yield galactose-1-P; (2) conversion of galactose-1-P and uridine diphosphate (UDP) glucose to UDP galactose and glucose-1-P by galactose-1-P uridyltransferase; (3) conversion of UDP-galactose to UDP-glucose by UDP-galactose-4-epimerase; and (4) conversion of UDP-glucose and diphosphate to glucose-1-P and uridine triphosphate by UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase(Reference Williams17). Of note, is an alternative pathway for step 2, known as the Isselbacher pathway, whereby galactose-1-P and uridine triphosphate are converted to UDP-galactose and diphosphate by the enzymes UDP-galactose pyrophosphorylase and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase(Reference Williams17). Some tracer studies have attempted to determine the metabolic fate of oral galactose in human subjects, estimating that during ingestion of galactose at a rate of 33 µmol/kg per min (about 135 g over 360 min), the splanchnic uptake of galactose is saturable at about 15 µmol/kg per min(Reference Sunehag and Haymond30, Reference Coss-Bu, Sunehag and Haymond31). At this rate of ingestion, it is estimated that about 30–60 % of the ingested galactose is converted into glucose(Reference Sunehag and Haymond30), mostly via the direct conversation of hexose to glucose (about 67 %), with some converted via the indirect (hexose to C3 substrates to glucose) pathway (about 33 %)(Reference Coss-Bu, Sunehag and Haymond31). Ultimately, the metabolic fate of ingested galactose in human subjects therefore remains incompletely understood, although it has been speculated that liver glycogen synthesis is a major route(Reference Niewoehner, Neil and Martin32, Reference Décombaz, Jentjens and Ith33) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. (Colour online) Major metabolic pathways of glucose, fructose and galactose in the human liver. TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; P, phosphate; UDP, uridine diphosphate. Based on(Reference Tappy and Lê10, Reference Williams17, Reference Mayes23–Reference Carmona and Freedland26, Reference Sunehag and Haymond30–Reference Décombaz, Jentjens and Ith33).

Hepatic metabolism of carbohydrates with exercise

Exercise increases energy expenditure, which is predominantly met during prolonged (>30 min) exercise by increases in both carbohydrate and fat oxidation compared with the resting state(Reference van Loon, Greenhaff and Constantin-Teodosiu34). The relative contributions of carbohydrate v. fat to exercise metabolism are influenced by the intensity and mode of exercise(Reference Achten, Venables and Jeukendrup35), preceding nutritional status(Reference Chen, Travers and Walhin36–Reference Edinburgh, Hengist and Smith38), endurance training status(Reference van Loon, Jeukendrup and Saris39) and biological sex(Reference Fletcher, Eves and Glover40). Specifically, higher carbohydrate oxidation rates are seen with cycling v. running(Reference Achten, Venables and Jeukendrup35), higher v. lower exercise intensity(Reference van Loon, Greenhaff and Constantin-Teodosiu34), prior carbohydrate feeding v. fasting(Reference Gonzalez, Veasey and Rumbold37), in individuals who are less v. more endurance-trained(Reference van Loon, Jeukendrup and Saris39) and amongst men v. women(Reference Fletcher, Eves and Glover40). Of these predictive factors, the intensity of exercise seems to be the most potent in determining carbohydrate and fat utilisation(Reference van Loon, Greenhaff and Constantin-Teodosiu34, Reference Romijn, Coyle and Sidossis41). Even in highly trained athletes studied in the overnight fasted state, carbohydrates are the predominant fuel source during moderate-to-high intensity (>50 % peak oxygen consumption) exercise(Reference van Loon, Greenhaff and Constantin-Teodosiu34). Exercise is therefore a potent modulator of carbohydrate metabolism, with implications for the fate of ingested carbohydrate.

The primary sources of carbohydrate supporting exercise metabolism are muscle glycogen, and circulating glucose and lactate(Reference van Loon, Greenhaff and Constantin-Teodosiu34). In the fasted state, almost all the circulating glucose is derived from hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, with minor contributions from the kidneys and intestine(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts5). When compared with the capacity to store fat, the relatively limited capacity for human subjects to store carbohydrate has implications for the ability to sustain moderate-to-high-intensity exercise(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts5). Even amongst lean individuals (about 10 % body fat), sufficient energy is stored as fat in adipose tissue to theoretically sustain moderate-to-high-intensity exercise for many weeks. However, utilising fat as a fuel has a number of limitations in the context of exercise performance. Fat is a relatively ‘slow’ fuel; the rate of ATP resynthesis with fat is at least half that when utilising muscle glycogen(Reference Walter, Vandenborne and Elliott42, Reference Hultman and Harris43). Fat is also an inefficient fuel on an oxygen basis, requiring about 10 % more oxygen consumption for an equivalent energy yield as glucose(Reference Jeukendrup and Wallis44). Consequently, during high-intensity exercise where rapid ATP resynthesis is required and/or muscle oxygen availability could be limiting, there are advantages to oxidising carbohydrates over fats. Finally, recent evidence implies that glycogen is more than just a fuel and is an important signalling molecule(Reference Ørtenblad, Westerblad and Nielsen45). Low glycogen concentrations in the intramyofibrillar region are associated with impaired sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release rates and excitation contraction coupling(Reference Ørtenblad and Nielsen46). Therefore, specific depots of glycogen appear to play important roles in both fuelling and regulating skeletal muscle contractile function, hence achieving high carbohydrate availability before and during competition is a goal for athletes competing in almost all endurance sports(Reference Thomas, Erdman and Burke47, Reference Burke, van Loon and Hawley48).

Low carbohydrate (glycogen) availability in muscle and liver is strongly associated with fatigue during prolonged exercise(Reference Bergström, Hermansen and Hultman49, Reference Casey, Mann and Banister50). The amount of glycogen stored in muscle and liver glycogen prior to single, or repeated bouts of exercise positively correlate with subsequent exercise capacity(Reference Bergström, Hermansen and Hultman49, Reference Casey, Mann and Banister50). A number of carbohydrate-related adaptations occur in response to regular endurance training that facilitate improvements in exercise performance. Endurance-trained athletes have a greater capacity to store muscle glycogen, and therefore display an increase in overnight-fasted muscle glycogen concentrations compared with people who are less endurance trained(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts5, Reference Areta and Hopkins51). This increase in basal muscle glycogen concentrations with endurance training is also exaggerated on a high-carbohydrate diet(Reference Areta and Hopkins51), suggesting that endurance-trained athletes can better tolerate high-carbohydrate diets by appropriately storing the excess carbohydrate as muscle glycogen. Interestingly, it seems that basal liver glycogen content does not adapt with endurance training, as endurance-trained athletes tend to exhibit similar liver glycogen concentrations to non-trained controls, when measured in the overnight fasted state(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts5). Whether this is also the case in the postprandial state remains to be established.

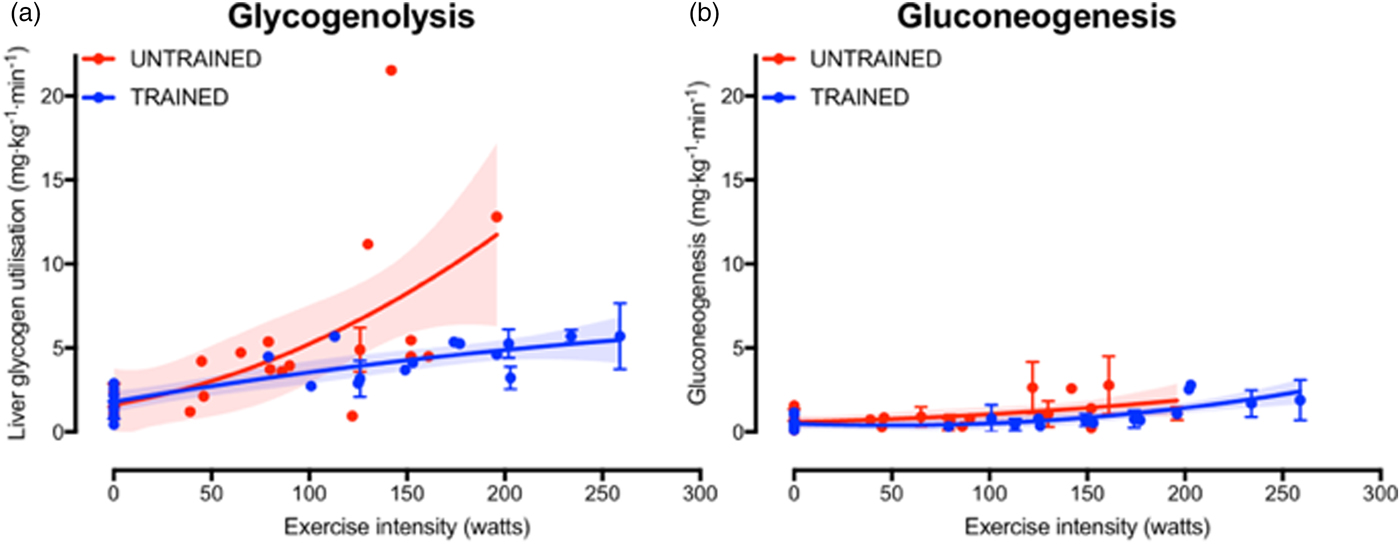

The increase in fasting muscle (but not liver) glycogen concentrations with endurance training provides trained athletes with a larger depot of glycogen to utilise during exercise and so postpones the point at which critically low muscle glycogen concentrations initiate fatigue. In addition to the greater storage capacity, trained athletes also utilise their muscle glycogen more conservatively during exercise(Reference Areta and Hopkins51). This sparing of glycogen with endurance training is not specific to muscle, as the rate of liver glycogen utilisation is also attenuated in endurance-trained athletes compared with controls, particularly at moderate-to-high exercise intensities(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts5). Evidence regarding whether gluconeogenesis is altered with endurance training is currently equivocal, as some studies indicate endurance training is associated with an increase in absolute rates of hepatic gluconeogenesis(Reference Bergman, Horning and Casazza52), whereas others have shown reductions in hepatic gluconeogenesis after endurance training(Reference Bergman, Horning and Casazza52). When pooling all the currently published studies that have concomitantly estimated hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis(Reference Bergman, Horning and Casazza52–Reference Webster, Noakes and Chacko66), it is clear that endurance training is associated with lower rates of glycogenolysis (Fig. 2(a), whereas any difference in gluconeogenesis with training status and/or exercise intensity is relatively small and unlikely to be quantitatively important (Fig. 2(b). Furthermore, it is apparent that hepatic glycogenolysis is the predominant source of blood glucose during exercise in an overnight fasted state, and the increase in endogenous glucose appearance with increasing exercise intensity is almost entirely met by an increase in hepatic glycogenolysis, rather than gluconeogenesis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. (Colour online) Hepatic glycogenolysis (a) and gluconeogenesis (b) in endurance trained individuals and untrained individuals. Each dot represents a group of participants or exercise intensity from a study, and error bars represent 95 % CI (only calculated when published data were available to permit this). The shaded areas represent the 95 % CI of the trend lines. Data are from(Reference Bergman, Horning and Casazza52–Reference Webster, Noakes and Chacko66).

Interactions between carbohydrate ingestion and exercise occur on multiple levels and in both directions. Ingesting carbohydrates during exercise can increase total carbohydrate oxidation and suppress net liver glycogen utilisation and fat oxidation(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Smith67). Whereas even modest exercise potently re-directs the metabolic fate of orally ingested sugars. For example, 60 min cycling at 100 W performed 90 min after fructose ingestion diverts more fructose away from storage (e.g. as glycogen) and increases fructose oxidation, without altering the conversion of fructose to glucose(Reference Egli, Lecoultre and Cros68). This may partly explain why daily exercise can completely prevent the increase in plasma TAG concentrations seen with high fructose intakes(Reference Egli, Lecoultre and Theytaz69). Remarkably, the protection offered from exercise against fructose-induced hypertriglyceridemia is seen independently from changes in net energy balance(Reference Egli, Lecoultre and Theytaz69), yet current recommendations for the health effects of dietary sugars rarely consider the context of physical activity status.

Since low carbohydrate availability is associated with impaired exercise tolerance, athletes engaging in competitive endurance events regularly consume carbohydrates during exercise(Reference Saris, van Erp-Baart and Brouns70). When ingesting glucose alone, the maximal rate at which human subjects can digest, absorb and metabolise glucose is about 1 g/min(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9), which typically only represents about 44 % of total carbohydrate oxidation during exercise at moderate intensity (about 60 % peak oxygen system) and is therefore insufficient to fully meet the carbohydrate requirements of cycling-based exercise(Reference Jentjens, Achten and Jeukendrup71). Consequently, oral ingestion of glucose is unable to prevent muscle glycogen depletion during prolonged exercise(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Smith67). It is thought that the primary limitation to the metabolism of orally ingested glucose lies in the splanchnic region, and intestinal absorption of glucose appears to be saturated at about 1 g/min(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9). Ingesting glucose at rates higher than 1 g/min during exercise is therefore likely to lead to accumulation of glucose in the gut and cause gastrointestinal distress. Interestingly, combining fructose with glucose appears to accelerate the digestion, absorption and utilisation of carbohydrate, such that exogenous carbohydrate oxidation rates can reach up to about 1·7 g/min, equating to about 70 % of total carbohydrate oxidation(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9, Reference Jentjens, Achten and Jeukendrup71). Under these conditions, the relative contribution from endogenous carbohydrate sources is therefore reduced from 100 % in the fasted state, to about 30 % with very high (2·5 g/min) carbohydrate ingestion rates(Reference Jentjens, Achten and Jeukendrup71). The primary mechanism by which fructose–glucose mixtures can increase exogenous carbohydrate oxidation over glucose alone is thought to be that intestinal fructose transport utilises a separate pathway than glucose. Specifically, whilst glucose absorption via sodium dependent GLUT-1 is saturated at about 1 g/min, fructose is primarily transported via GLUT5, thereby taking advantage of this alternative pathway and delivering more total carbohydrate to the system(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9).

Potential implications and applications

Exercise performance

The health and performance implications of carbohydrate intake can be dependent on the specific pathways through which different dietary sugars are absorbed and metabolised. In terms of endurance performance, the accelerated digestion, absorption and utilisation of fructose–glucose mixtures above glucose only, has potential benefits with regard to sparing glycogen stores whilst minimising gastrointestinal distress during exercise(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9). Gastrointestinal complaints are relatively common in endurance events(Reference Pfeiffer, Stellingwerff and Hodgson72), which may directly impair performance, but also limit the ability to ingest adequate nutrition to fuel the demands of the exercise. It has recently been demonstrated that the ingestion of either glucose alone, or sucrose (glucose–fructose) can prevent liver glycogen depletion during prolonged (3 h) cycling at a moderate exercise intensity (55 % VO2max)(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Smith67). Whilst there was no further benefit of ingesting sucrose compared with glucose with respect to net liver glycogen depletion, the prevention of liver glycogen depletion with sucrose ingestion was attained with lower ratings of both gut discomfort and perceived exertion, compared with glucose ingestion(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Smith67). Furthermore, when carbohydrates are ingested in large amounts during exercise (>1·4 g/min), the ingestion of glucose–fructose enhances endurance performance by about 1–9 % more than when glucose is ingested alone(Reference Rowlands, Houltham and Musa-Veloso73). Conversely, galactose appears to display relatively low rates of exogenous carbohydrate oxidation during exercise (about 0·4 g/min oxidised, when ingesting about 1·2 g/min), despite an apparent potential for faster intestinal absorption of galactose compared with glucose in perfusion studies(Reference Holdsworth and Dawson74, Reference Cook75). Moreover, since galactose primarily shares a common intestinal absorption pathway to glucose, combining galactose and glucose ingestion is unlikely to provide the same benefits for exogenous carbohydrate availability and endurance performance as glucose–fructose co-ingestion.

In addition to manipulating carbohydrate availability during exercise, dietary sugars can also play an important role during post-exercise recovery, particularly in multi-stage events such as the Tour de France and the Marathon des Sables, where athletes are required to perform to the best of their ability with <24 h recovery. Within these scenarios, the primary limiting factor to recovery time is glycogen storage rate(Reference Burke, van Loon and Hawley48, Reference Alghannam, Gonzalez and Betts76). Even with high carbohydrate intakes, it is thought to take between 20 and 24 h to fully restore muscle glycogen concentrations after exhaustive exercise(Reference Coyle77). Thus, on moderate carbohydrate diet, muscle glycogen repletion can take up to 46 h(Reference Piehl78). Therefore, intensive nutritional strategies can be applied to optimise muscle glycogen resynthesis post-exercise. Post-exercise muscle glycogen resynthesis rates display a biphasic response, with the most rapid net synthesis seen within the first 30 min following exercise in an insulin-independent phase(Reference Price, Rothman and Taylor79). Following this period, muscle glycogen synthesis rates become insulin-dependent and can fall to at least half the rate of that seen within the first 30 min post-exercise(Reference Price, Rothman and Taylor79). Muscle glycogen resynthesis rates are maximally stimulated with carbohydrate ingestion rates of ≥1 g/kg body mass per h(Reference Burke, van Loon and Hawley48, Reference Alghannam, Gonzalez and Betts76), and this ingestion rate is also associated with optimal restoration of endurance capacity during short-term (4 h) recovery periods(Reference Alghannam, Gonzalez and Betts76). Therefore, athletes are advised to consume carbohydrate at a rate of 1–1·2 g carbohydrate/kg body mass per h during the early stages (4 h) of recovery(Reference Thomas, Erdman and Burke47, Reference Burke, van Loon and Hawley48) and, when these ingestion rates are not achievable, the addition of certain (insulinotropic) proteins, such as milk proteins, to carbohydrate can potentially increase the efficiency of muscle glycogen resynthesis(Reference Betts and Williams80).

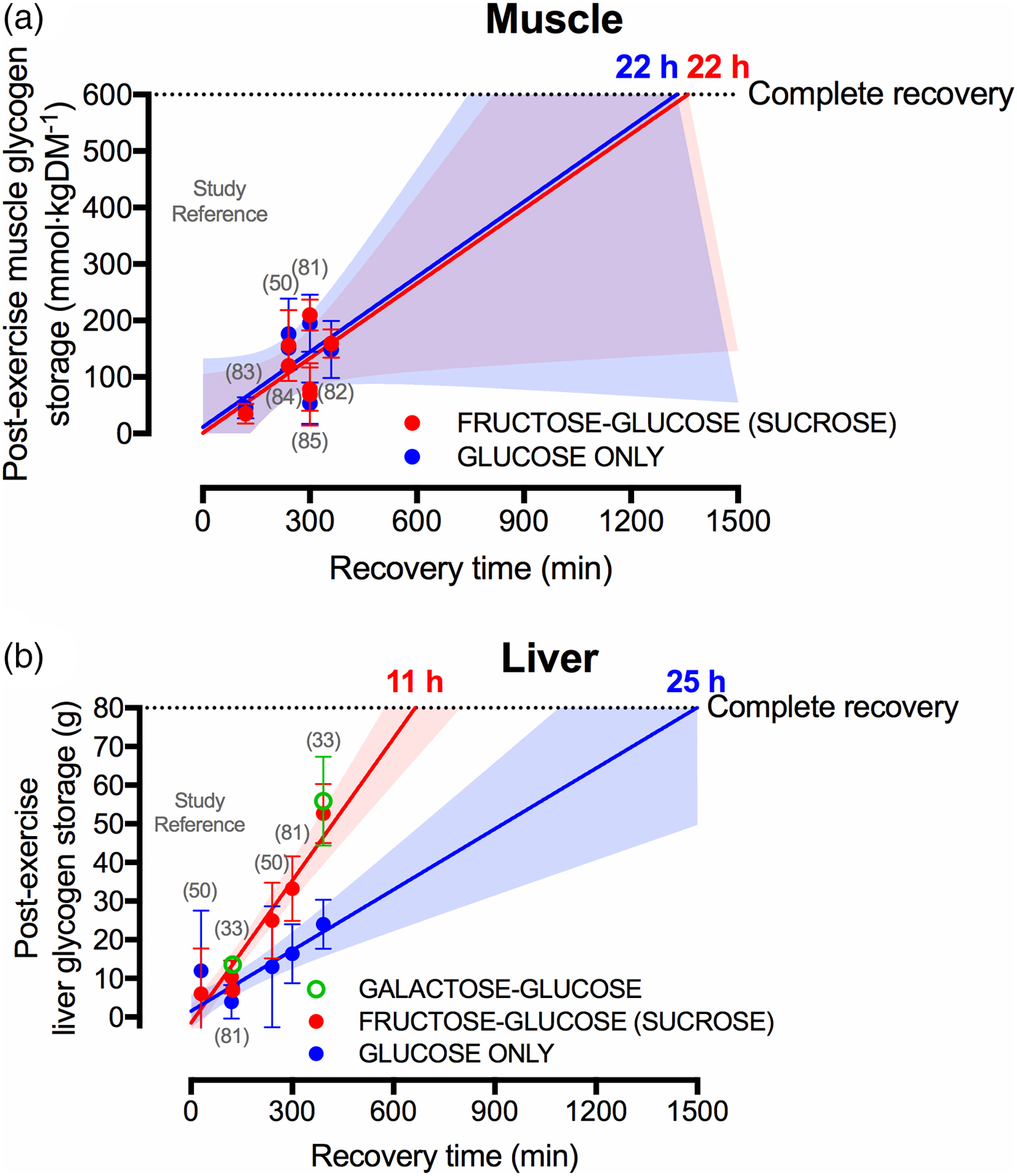

Current sports nutrition guidelines for recovery do not specify whether the carbohydrate should be from a particular source of sugar (e.g. glucose v. fructose v. galactose)(Reference Thomas, Erdman and Burke47, Reference Burke, van Loon and Hawley48), which is understandable given that muscle glycogen resynthesis rates do not appear to differ whether glucose or glucose–fructose mixtures are ingested(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9, Reference Fuchs, Gonzalez and Beelen81), yet overlooks the clear potential for sugars to differentially affect liver glycogen resynthesis. Indeed, when pooling all currently published data that compare glucose with glucose–fructose mixtures in crossover designs(Reference Casey, Mann and Banister50, Reference Fuchs, Gonzalez and Beelen81–Reference Trommelen, Beelen and Pinckaers85), it is apparent that post-exercise muscle glycogen resynthesis rates do not differ between glucose ingested alone v. glucose–fructose (sucrose) mixtures (Fig. 3(a)). Extrapolating these data would suggest that 22 h are required to completely re-synthesise muscle glycogen from a fully depleted state, when following current sports nutrition guidelines, regardless of the type of carbohydrate ingested (Fig. 3(a)). This indicates that intestinal absorption of carbohydrate is not rate-limiting to post-exercise muscle glycogen resynthesis. Conversely, liver glycogen resynthesis appears to be potently accelerated by glucose–fructose co-ingestion compared with glucose (polymers) alone (Fig. 3(b))(Reference Décombaz, Jentjens and Ith33, Reference Casey, Mann and Banister50, Reference Fuchs, Gonzalez and Beelen81), which may be in part due to greater exogenous carbohydrate availability and/or the specific hepatic metabolism of fructose.

Fig. 3. (Colour online) Studies (specified by reference citations) that have directly compared glucose ingestion alone, with either fructose–glucose or galactose–glucose mixtures, and measure rates of muscle (a) and liver (b) glycogen repletion post-exercise. Each circle represents a timepoint within a study. Error bars represent 95 % CI, and the shaded areas represent the 95 % CI of the trend line. For complete recovery of muscle glycogen stores, 600 mm/kgDM was chosen on the basis that muscle glycogen concentrations at exhaustion is typically about 115 mm/kgDM and the maximal muscle glycogen concentrations of relatively well-trained athletes (60–70/ml/kg per min) is between 600 and 800 mm/kgDM(Reference Areta and Hopkins51). For complete recovery of liver glycogen stores, 80 g was chosen on the basis that liver glycogen concentrations in the overnight fasted state are about 280 mm/l. Assuming a liver volume of 1·8 litre and the molar mass of a glycosyl unit being 162 g/m, this equates to 80 g glycogen(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts5).

A further interesting observation is that liver glycogen resynthesis rates also appear to show a bi-phasic, time-dependent response, albeit in the opposite direction to skeletal muscle. Within the first 2 h post-exercise, net liver glycogen resynthesis rates are about 30–50 % slower than the 3–5 h period, independent of the type of carbohydrate ingested (2 (se 2) and 5 (se 2) g/h in the 0–2 h post-exercise v. 4 (se 2) and 8 (se 2) g/h in the 2–5 h post-exercise, with glucose and sucrose ingestion, respectively)(Reference Fuchs, Gonzalez and Beelen81). Furthermore, with high rates of carbohydrate ingestion, fructose–glucose mixtures can reduce ratings of gut discomfort during recovery from exercise, compared with glucose ingestion alone(Reference Fuchs, Gonzalez and Beelen81). Extrapolating these data (i.e. assuming that the first 6·5 h is representative of a full 24 h period) indicates that when only glucose is ingested, complete recovery of liver glycogen stores may take about 25 h (Fig. 3(b)). However, when glucose–fructose mixtures are ingested, then liver glycogen repletion could take as little at 11 h (Fig. 3(b)). When considering that the time between ending a stage and beginning the next stage in the Tour de France can be about 15 h, the accelerated recovery of liver glycogen stores with fructose–glucose mixtures is highly meaningful from a practical standpoint.

Interestingly, fructose is not the only sugar that more rapidly replenishes liver glycogen contents following exercise than glucose alone. The addition of galactose to glucose also accelerates post-exercise liver glycogen repletion when matched for total carbohydrate intake(Reference Décombaz, Jentjens and Ith33), and to a similar extent as fructose–glucose ingestion (Fig. 3(b)). Since intestinal galactose–glucose absorption should theoretically be slower than fructose–glucose absorption, it is tempting to speculate that the mechanisms by which fructose and galactose enhance liver glycogen resynthesis relate to hepatic metabolism, rather than intestinal absorption. These data also raise the following question: if the Leloir pathway (direct galactose–glucose conversion) is the primary pathway of human galactose metabolism, why is the liver glycogenic response to galactose ingestion more comparable to fructose than to glucose? With regard to generating useful data for applied practice, there is a need to establish the optimal dose and mixture of sugars for rapid liver glycogen resynthesis and whether this translates into improved endurance performance. Accordingly, dose–response studies and direct comparisons of combined galactose–fructose–glucose are warranted.

Whilst the effects of fructose–glucose and galactose–glucose ingestion on glycogen resynthesis are interesting and likely to be important for athletic performance, this will remain speculative in the absence of empirical data. Fortunately, a recent study compared the recovery of exercise capacity with glucose–maltodextrin ingestion v. fructose–maltodextrin ingestion(Reference Maunder, Podlogar and Wallis86). Since the maltodextrin is hydrolysed, absorbed and oxidised as quickly as free glucose(Reference Gonzalez, Fuchs and Betts9), it can be considered the glucose–maltodextrin is physiologically almost identical to ingesting pure glucose. Athletes were first asked to run on a treadmill at 70 % ![]() $\dot{\rm V}{\rm O}_{2\max}$ to exhaustion. Following this, the athletes ingested 90 g carbohydrate/h during a 4 h recovery period as either a glucose–maltodextrin mixture, or fructose–maltodextrin mixture. After the recovery period, the athletes ran on the treadmill again at 70 %

$\dot{\rm V}{\rm O}_{2\max}$ to exhaustion. Following this, the athletes ingested 90 g carbohydrate/h during a 4 h recovery period as either a glucose–maltodextrin mixture, or fructose–maltodextrin mixture. After the recovery period, the athletes ran on the treadmill again at 70 % ![]() $\dot {\rm V}{\rm O}_{2\max}$ to exhaustion. During the glucose–maltodextrin trial, the second-bout capacity for these athletes to run was 61·4 (se 9·6) min, whereas, when fructose–maltodextrin was ingested in the recovery period, these athletes ran for 81·4 (se 22·3) min representing an improvement in second-bout endurance capacity of about 30 %(Reference Maunder, Podlogar and Wallis86). This provides the first evidence that fructose–glucose ingestion accelerates recovery of exercise capacity. When considered in light of the consistently reported acceleration of liver glycogen recovery, it may be sensible for athletes requiring rapid recovery during multi-stage events to consume fructose–glucose mixtures rather than glucose only. In terms of applying this in practice, it could mean the use of fruit smoothies to supplement carbohydrate intake rather than the commonly held view that pasta is a preferable choice for carbohydrate loading.

$\dot {\rm V}{\rm O}_{2\max}$ to exhaustion. During the glucose–maltodextrin trial, the second-bout capacity for these athletes to run was 61·4 (se 9·6) min, whereas, when fructose–maltodextrin was ingested in the recovery period, these athletes ran for 81·4 (se 22·3) min representing an improvement in second-bout endurance capacity of about 30 %(Reference Maunder, Podlogar and Wallis86). This provides the first evidence that fructose–glucose ingestion accelerates recovery of exercise capacity. When considered in light of the consistently reported acceleration of liver glycogen recovery, it may be sensible for athletes requiring rapid recovery during multi-stage events to consume fructose–glucose mixtures rather than glucose only. In terms of applying this in practice, it could mean the use of fruit smoothies to supplement carbohydrate intake rather than the commonly held view that pasta is a preferable choice for carbohydrate loading.

Metabolic health

The impact of dietary sugars on hepatic metabolism also has potential metabolic health consequences. Public health recommendations to limit intake of free sugars are primarily based on the effects of diets high in free sugars on body weight and associations with dental caries(11). However, distinct metabolic effects of fructose in particular receive much interest with respect to metabolic health. Metabolic health is typically characterised by the ability to maintain relatively stable blood glucose and lipid concentrations in the postprandial state(Reference Edinburgh, Betts and Burns87), since high postprandial glucose and/or TAG concentrations are associated with CVD(Reference Nordestgaard, Benn and Schnohr88, Reference Ning, Zhang and Dekker89). The ability to maintain relatively stable circulating metabolite concentrations with relatively little need for insulin represents an important aspect of insulin sensitivity, which is thought to be a fundamental mechanism by which metabolic health is sustained. Whilst insulin sensitivity is most commonly associated with blood glucose control, the many regulatory roles of insulin mean that insulin sensitivity is best considered with respect to the tissue of interest and function of interest. For example, insulin sensitivity of skeletal muscle to glucose uptake, insulin sensitivity of the liver to glucose output, or insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue to lipolysis, etc. This is relevant when discussing the role of fructose in metabolic health as it is apparent that most of the metabolic effects of fructose occur in a tissue-specific manner.

The addition of fructose to other ingested nutrients can impact both postprandial glucose and lipid metabolism. Low doses of fructose can in fact lower postprandial glycaemia via increased hepatic glucose disposal secondary to fructose-1-P antagonisation of glucokinase regulatory protein, and thereby enhanced hepatic glucokinase activity(Reference Van Schaftingen, Detheux and Veiga da Cunha90–Reference Sievenpiper, Chiavaroli and de Souza92). However, compared with glucose ingestion, fructose can enhance postprandial TAG concentrations acutely(Reference Chong, Fielding and Frayn19) and supplementation of fructose over days/weeks can increase fasting plasma glucose, insulin and TAG concentrations, and increase liver fat content, particularly in overweight/obese populations and during positive energy balance(Reference Stanhope, Schwarz and Keim93, Reference Lecoultre, Egli and Carrel94). However, some have shown that a positive energy balance and/or saturated fat intake are more potent drivers of liver fat accumulation than specific effects of fructose over glucose(Reference Johnston, Stephenson and Crossland95, Reference Luukkonen, Sädevirta and Zhou96). The mechanisms underlying these metabolic changes with fructose ingestion, are thought to include a suppression of hepatic insulin sensitivity to glucose output, stimulation of de novo lipogenesis via activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase (up-regulated when glycogen concentrations are high(Reference Kiilerich, Gudmundsson and Birk97)), and a reduction in hepatic fatty acid oxidation, leading to increased net lipid synthesis and VLDL-TAG production and secretion(Reference Tappy and Lê10, Reference Egli, Lecoultre and Theytaz69, Reference Lecoultre, Egli and Carrel94, Reference Park, Cesar and Faix98). This is consistent with data pertaining to post-exercise glycogen resynthesis, since it is thought that insulin resistance to skeletal muscle glucose uptake (leading to hyperglycaemia) and de novo lipogenesis (leading to hypertriglyceridemia) are up-regulated when glycogen stores are saturated(Reference Petersen, Price and Bergeron63, Reference Rabøl, Petersen and Dufour99, Reference Nolte, Gulve and Holloszy100). Furthermore, during non-exercise conditions, the increase in postprandial liver glycogen concentrations seen with a 7 d high-glycaemic index diet occurs in tandem with increases in liver fat content(Reference Bawden, Stephenson and Falcone101). The proposed relationship between liver glycogen and lipid metabolism supports the idea that regular exercise can obliterate the negative effects of fructose overfeeding in healthy men(Reference Gonzalez and Betts8, Reference Egli, Lecoultre and Theytaz69), since exercise results in rapid glycogen turnover, and there is clear evidence that the carbohydrate deficit from exercise is a key factor in exercise-induced increases in whole-body glucose control(Reference Taylor, Wu and Chen102).

Whether exercise can be protective against fructose-induced hypertriglyceridaemia and changes in hepatic insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese populations remains to be established. Given the role of glycogen status in metabolic health, it could be speculated that, when metabolic control is the primary aim, the avoidance of carbohydrates (and in particular fructose-containing sugars) for periods before, during and/or after exercise could better maintain some of the insulin-sensitising effects of exercise via greater liver glycogen depletion and delayed liver glycogen repletion (Fig. 3), but this has never been empirically assessed. Fructose can therefore induce changes that are associated with impaired metabolic health, but this appears to be primarily in sedentary, overweight and obese individuals, and when in a positive energy balance. There is evidence that regular exercise has the potential to protect against most (if not all) of these metabolic effects, at least in healthy men. Research is required to determine whether exercise can be protective against metabolic changes with fructose supplementation in people at risk of metabolic disease, and if so, then to characterise the lowest ‘dose’ of exercise that is protective.

Conclusions

The liver is a primary site of carbohydrate metabolism and particularly the metabolism of fructose and galactose-containing sugars. Hepatic metabolism plays a key role in metabolic health and endurance exercise performance, by assisting in the maintenance of blood glucose and lipid homeostasis during rapid changes in the supply and demand for energy, such as with fasting-feeding cycles and with physical activity. In the fasted state, the liver provides almost all the glucose necessary to maintain blood glucose concentrations during exercise. As exercise intensity increases, thereby accelerating the demand for glucose by skeletal muscle, the increase in liver glucose output is primarily met by releasing stored glucose from glycogen, rather than by increases in de novo synthesis of glucose by gluconeogenesis. Similarly, the reduction in liver glucose output during exercise seen in endurance-trained athletes compared with untrained controls, is primarily driven by a reduction in glycogenolysis, as opposed to changes in gluconeogenesis. Therefore, prolonged exercise of a moderate-to-high intensity leads to a depletion of liver glycogen stores unless carbohydrate is ingested during exercise, particularly in less-trained individuals.

For endurance athletes who require rapid recovery for subsequent competitive events, restoration of skeletal muscle and liver glycogen stores are a primary goal. Carbohydrate ingestion is a requirement to replenish glycogen stores within a 24 h timeframe, and ingesting carbohydrate at a rate of about 1 g/kg body mass per h within the early (0–4 h) recovery period can assist in optimising this process. Whilst muscle glycogen repletion appears to be largely unaffected by the specific presence of fructose in ingested carbohydrates, liver glycogen repletion rates are potently enhanced by the ingestion of fructose- or galactose-containing sugars, when compared with glucose alone. There is evidence that the complete restoration of liver glycogen stores after exhaustive exercise could be accelerated by as much as 2-fold with the ingestion of fructose–glucose mixtures, compared with glucose-only carbohydrates. Therefore, athletes with multiple competitive events within a 24 h period should aim to consume about 1 g/kg body mass per h carbohydrate with foods providing fructose and glucose. Not only does this enhance restoration of liver (and therefore total body) glycogen stores, there is now evidence that this can reduce the gut discomfort associated with high-carbohydrate ingestion rates, and improve endurance running capacity. There is, however further work required to establish the optimal dose and mixture of carbohydrates to be ingested to maximise post-exercise liver glycogen recovery.

The rapid restoration of liver glycogen stores is relevant mainly to a small minority of the population engaging in relatively extreme events. Most people are more concerned about their health than competing in an ultra-endurance event. However, the same knowledge gained about the physiological responses to dietary sugars and exercise, particularly hepatic metabolism, can also be applied to improve metabolic health. Fructose-containing sugars have been implicated in inducing hyperglycaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, hepatic insulin resistance and increases in liver fat content, particularly in overweight/obese populations and when in a positive energy balance. Interestingly, there is evidence in young, healthy men that modest amounts of exercise can completely protect against almost all of these potentially deleterious effects of high-fructose intakes, independent of energy balance. The protective effects of exercise may be due to the carbohydrate deficit and/or glycogen turnover in the liver and skeletal muscle induced by physical activity. Accordingly, specifically avoiding carbohydrates at key times: either before, during and/or after exercise to augment and preserve a glycogen deficit could be a strategy to enhance metabolic health. However, it is not known if exercise can be protective in populations at risk of metabolic disease, which should be a future research priority.

Financial Support

J. T. G. has received research funding from The European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, The Rank Prize Funds, The Physiological Society (UK), The Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (UK), The Medical Research Council (UK), Arla Foods Ingredients, Lucozade Ribena Suntory and Kenniscentrum Suiker and Voeding, and has acted as a consultant to PepsiCo. J. A. B. has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline Nutritional Healthcare R&D, Lucozade Ribena Suntory and Kelloggs, has acted as a consultant for Lucozade Ribena Suntory and PepsiCo and is a scientific advisor to the International Life Sciences Institute Europe Task Force on Energy Balance. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

J. T. G. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Both authors read, edited and approved of the final manuscript.