Saharawi refugees have been hosted in camps in Tindouf, south-west Algeria, since 1975. Since that time the Government of Algeria has supplied relief items. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has supported the government in meeting refugees’ basic needs and opened an office in Algiers in 1985. The World Food Programme has supplied food assistance since 1986, and a range of donors and bilateral arrangements currently support the refugee population. Anaemia and chronic malnutrition were major public health problems, affecting 62 % and 32 % of children aged 6–59 months in the Saharawi refugee camps in Algeria in 2008( 1 ). Similarly, anaemia prevalence was high in women, reaching 54 % in 2008( 1 ). A previous trial carried out in 1999 using a high-nutrient-density spread for 6 months showed positive benefits in correcting retarded linear growth and reducing anaemia and stunting in children( Reference Lopriore, Guidoum and Briend 2 ). However, the use of this type of spread was not continued and anaemia prevalence in young children almost doubled after the end of that intervention.

In 2009, as part of the UNHCR’s Anaemia Strategy( 3 ), two special nutritional products, a lipid-based nutrient supplement (LNS) and a micronutrient powder (MNP), were proposed for use in blanket supplementary feeding programmes as part of a prevention strategy to address the problems of anaemia and stunting. These two products were chosen due to the positive outcomes shown in recent studies. Studies in Malawi( Reference Phuka, Maleta and Thakwalakwa 4 , Reference Phuka, Gladstone and Maleta 5 ) and Ghana( Reference Adu-Afarwuah, Lartey and Brown 6 , Reference Dewey and Adu-Afarwuah 7 ) showed a promising impact on linear growth, iron status and motor development when the LNS was added to the diet in small amounts (about 20–75 g/d). Bioavailability studies on MNP have shown that iron is well absorbed in infants( Reference Tondeur, Schauer and Christofides 8 , Reference Zlotkin, Schauer and Owusu Agyei 9 ) and multiple randomized studies have demonstrated the efficacy of MNP in treating anaemia in young children( Reference Dewey, Yang and Boy 10 ).

The acceptability of various LNS and MNP products was previously tested and generally found to be high in Pakistan( Reference Khan, Hyder and Tondeur 11 ), Ghana( Reference Adu-Afarwuah, Lartey and Zeilani 12 ), Burkina Faso( Reference Hess, Bado and Aaron 13 , Reference Abbeddou, Hess and Jimenez 14 ) and Malawi( Reference Phuka, Ashorn and Ashorn 15 ). However, studies in refugee contexts have indicated that MNP is not always well accepted and that adherence can be low( Reference Kodish, Rah and Kraemer 16 ). When introducing any nutrition or health intervention, including within refugee contexts, the issues of acceptability and adherence in the local context should be key considerations( Reference Tripp, Mackeith and Woodruff 17 ).

Therefore, prior to the initiation of a blanket supplementary feeding programme to reduce anaemia and stunting within the refugee camps in Algeria, a field-based study was designed and conducted. The objectives of the study were to: (i) assess the acceptability of an LNS (Nutributter®) in children 6–35 months old and an MNP in children 36–59 months old and pregnant and lactating women; (ii) determine adherence to the recommended doses after 15 d of use; and (iii) investigate appropriate information messages and distribution mechanisms.

Methods

Study location

The LNS acceptability test was implemented in 2009 in four Saharawi refugee camps in south-west Algeria; namely Smara, Laayoune, Awserd and Dakhla. The MNP acceptability test was implemented only in Smara camp. The camps lie close to the city of Tindouf and are characterized by a harsh desert environment where sandstorms are frequent, with extremely high temperature throughout the months of May to September (reaching above 50°C) and a cold winter season from November to March. Rainfall is scarce and irregular. The refugee population originated from Western Sahara and is predominantly Sunni Muslim. Refugee houses are made of local building materials and complemented with tents. The tents are regarded as suitable for the extreme weather and provide relatively cool accommodation during the hot season( 18 ).

Product formulation

Because excessive iodine intake is a problem among Saharawi refugees( 1 , Reference Seal, Creeke and Gnat 19 , 20 ), the Nutributter® formulation was adjusted by removing iodine from the fortificant premix (Table 1). However, it was not feasible to alter the MNP formulation at the time of the study and hence the MNP was used only in the camp where iodine intakes are acceptable due to the presence of a reverse osmosis plant that demineralizes household drinking-water, thereby decreasing overall iodine intake.

Table 1 Nutrient composition of the nutrition products

LNS, lipid-based nutrient supplement; MNP, micronutrient powder.

Ethical approval

The Saharawi Ministry of Health approved the implementation of the study and stated that formal ethical approval need not be sought. An authorization letter to conduct the assessment was signed by the Ministry of Health prior to the start of the assessment. The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. All potential participants received information about the assessment before enrolment. Those wishing to participate signed an informed consent form indicating the voluntary nature of the test and their right to discontinue follow-up at any point.

Study design and participants

The study included two main components: (i) a quantitative measurement of acceptability and adherence that involved conducting interviews with participants at household level; and (ii) a qualitative component that involved focus group discussions.

Three population groups were selected for the quantitative measurements, corresponding to the target groups that were planned for the subsequent supplementary feeding programme. Children aged 6–35 months were given LNS while children aged 36–59 months and pregnant and lactating women were given MNP. These target groups were recommended by the UNHCR-–World Food Programme Joint Assessment Mission conducted in 2009 in the camps( 18 ). The growth monitoring programme for children aged 6–59 months running in the camps was split in two groups: children aged 6–35 months and 36–59 months. Hence, the target age group for the LNS, which is usually 6–23 months, was expanded to include children up until age 35 months to ensure the feasibility of incorporating product distributions into ongoing programmes.

The sample size needed to assess acceptability and adherence to both products at the household level was calculated using an expected proportion of 50 % adherence, 5 % error risk, 10 % precision and an expected 20 % loss to follow-up. The sample size was calculated using ENA for SMART software (version October 2007) and was 114 for each group.

At the beginning of the study, key meetings at various levels were arranged with the health authorities, health staff, parents, and pregnant and lactating women in all camps. The objectives of these meetings were to inform them about the nutrition products and the planned test, and seek their full cooperation and participation.

Purposive sampling was used to select the participants. Eligible participants were identified through the growth monitoring programme or the antenatal care clinics from the registers in the health centres. To ensure participants were equally distributed throughout the camps, the same number of participants was selected from each health centre. Children meeting the age criteria whose parents showed an initial interest in the test and pregnant and lactating women were invited for a preliminary screening. Those who met all eligibility criteria and gave their consent to participate were enrolled. The age of the children was confirmed using their health card.

For the MNP group, children aged 36–59 months were recruited in August 2009 based on the following inclusion criteria: enrolled in the camp’s growth monitoring programme and available to participate during the entire study period. Pregnant and lactating women were selected in August 2009 based on the following inclusion criteria: enrolled in the camp’s antenatal care clinic and available during the study period. Children aged 36–59 months were excluded if they had a severe systemic illness warranting hospital referral, had a weight-for-height Z-score below or equal to −2 according to WHO 2006 Growth Standards, were receiving therapeutic care for anaemia or were involved in another study. Pregnant and lactating women were excluded if they had a severe systemic illness warranting hospital referral, were receiving therapeutic care for anaemia or were involved in another study.

For the LNS group, children aged 6–35 months were recruited in September 2009. The recruitment of participants and distribution of LNS occurred later than for MNP due to a delay in customs clearance during importation of the product. Recruitment was based on the following inclusion criteria: enrolled in the camp’s growth monitoring programme, eating complementary foods in addition to breast milk (at least one meal per day) and available to participate during the entire study period. Children aged 6–35 months were excluded if they had a severe systemic illness warranting hospital referral, had a history of allergy towards peanuts, had a history of anaphylaxis or serious allergic reaction to any substance requiring emergency medical care, were enrolled in the camp’s therapeutic or supplementary feeding programmes for acute malnutrition, had a weight-for-height Z-score below or equal to −2 according to WHO 2006 Growth Standards, were receiving therapeutic care for anaemia, had congenital defects such as cleft palate or any illness likely to interfere with food intake, or were involved in another study.

For focus group discussions, a sub-sample of participants was conveniently selected from specific groups of interest to investigate issues around acceptability and use of the products. To inform the content of the focus group discussion guides, key informant interviews were conducted with members of the health authorities, community leaders, religious leaders, traditional medicine healers and health staff. Respondents were conveniently sampled and four key informant interviews were carried out with the health authorities, two with the community leaders in Smara and in Dakhla, six with the health staff from Smara, Dakhla and Laayoune, one with a religious leader in Smara and one with a traditional medicine healer in Awserd. Data collection for the MNP group took place from 29 July to 11 September and for the Nutributter® group from 12 September to 15 October, 2009.

Procedures

The Saharawi Ministry of Health selected the health staff teams for data collection. A total of fifty-two health staff members were trained in the four camps. Teams were trained on how to prepare complementary foods with MNP, the correct use of LNS, dosages and administration. Other issues covered in the training included an explanation of the teams’ tasks and responsibilities, and procedures for monitoring, quality control, household visits and follow-up visits. Each health staff member was provided with a flip chart containing nutritional information on how to use LNS and MNP.

Twenty-six teams were created to conduct the household interviews and were organized by camp and supervised by two sets of field supervisors: thirteen teams worked in Smara and Awserd, and thirteen teams covered the Dakhla and Laayoune camps. Each team was composed of two people from the clinic, i.e. the head of the clinic (nurse) and an auxiliary health staff member. Teams conducted the household visits during the mealtime (lunch or dinner) in order to carry out the interviews and perform direct observations of how the products were stored in the household. Information on household location and composition was recorded, but it was not deemed necessary or useful to collect lengthy sociodemographic information on the participants due to the relative homogeneity of the camp population.

Initial nutrition education sessions on how to use the LNS and the MNP were given by health staff to women participants in small groups (five to ten persons) in the clinics of two camps (Smara and Dakhla) and at the individual level in the other two camps (Laayoune and Awserd). Instructions on how to use the nutrition products and the dosage were the main focus of the session. Education material was specifically developed for this purpose with key instructions and messages on the different products. All participants, or their caregivers, were instructed to take the nutrition product daily for four weeks and were asked to keep the empty sachets so they could be counted. The recommended schedule of use for all the participants was one sachet per day, i.e. a 20 g sachet of LNS or a 1 g sachet of MNP. A total of thirty LNS or thirty MNP sachets were distributed to the caregivers and to the pregnant and lactating women by the study staff at the beginning of the test in plastic bags, either at the clinic or in their homes.

Household interviews were conducted at baseline and acceptability, consumption and adherence were assessed through household visits at mid point (15 d) and at the end of the test (30 d), during which interviews on acceptability were conducted and empty sachets were counted. The numbers of lost or discarded empty sachets and shared sachets were also assessed by interview. Consumption was classified using the percentage of sachets consumed over the dose recommended for the defined period of time: ‘very low’ (<25 %); ‘low’ (25–<75 %); ‘optimal’ (75–125 %); or ‘excessive’ (>125 %). Individual adherence was defined using the mid-point consumption measurement as: ‘poor’ if consumption was very low or excessive; ‘moderate’ if consumption was low; or ‘good’ if consumption was optimal. Population adherence was considered adequate if >70 % of participants displayed good or moderate adherence. A product was considered acceptable if ≥75 % of participants reported liking it at the end of the test period and ≤20 % would prefer to stop taking it.

Focus group discussions were conducted in convenient locations in the different camps, such as health centres or community buildings, which participants were invited to attend. Groups were facilitated by the field researcher (a female, Spanish, nutritionist) assisted by a local interpreter. The major themes covered in the focus group discussions were as follows: household eating habits; superstitions related to food; likeability of the products; sharing of products; food preparation; effects on food; adverse effects; perceived benefits; perceptions of the products; products distribution; and barriers to use. Findings were recorded by the field researcher taking manual notes during the interviews.

Initial statistical analysis of quantitative data was done using Epi Info software (version 3·5). Graphing and statistical testing of sachet consumption (Kruskal–Wallis rank test) was carried out in the statistical software package Stata I/C version 12·1. Significance was assigned when P<0·05. Qualitative data from focus group discussions were analysed manually by topic to identify the main emergent themes, consistencies, differences and relationships. Findings were recorded and compiled in an Excel spreadsheet.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the sample selected for the quantitative household interviews. A total of 123 children aged 6–35 months were recruited at baseline and given LNS. The LNS results are presented for all four camps combined, as similar results were found in each camp. For the MNP group a total of 112 children, aged 36–59 months, and 119 pregnant and lactating women were recruited from 206 households in Smara camp at baseline. Average household size was 6·0 in Smara with 2·3 children under 5 years of age. In the other camps, the average number of children under 5 years of age was also 2·3. In the LNS group, there was one loss to follow-up. In the MNP group, there were two losses to follow-up for children and one for pregnant or lactating women. Some of the household interview questionnaires had a high percentage of missing data, ranging from 11 % of the questionnaire in the LNS group up to 34 % of the questionnaire in the MNP group. For children, the respondents were the mothers in 88·6 % of the cases in the LNS group and 96·2 % of the cases in the MNP group. In the other cases, the respondent was another member of the household.

Table 2 Characteristics of the quantitative study sample, Saharawi refugee camps, Algeria, August–October 2009

LNS, lipid-based nutrient supplement; MNP, micronutrient powder.

Acceptability

Acceptability was assessed both quantitatively and qualitatively (see below). Differences in measures of acceptability were compared statistically at the endline of the study. As shown in Table 3, there was a significant difference between all three product groups in the proportion of participants reporting that they liked the product, with 98·4 % liking LNS compared with 90·4 % of women consuming MNP and 75·5 % of children using MNP (P<0·05). There were no significant differences in other measures of acceptability with >90 % of participants in all groups finding the products easy to use and <10 % reporting that they would prefer to stop using the product or that they shared sachets during the test.

Table 3 Acceptability and use of products at mid point (after 15 d) and endline of the 30 d assessment among the quantitative study sample, Saharawi refugee camps, Algeria, August–October 2009

LNS, lipid-based nutrient supplement; MNP, micronutrient powder.

* Indicates a different response compared with other product groups at endline (P<0·05).

† Data on sharing were not collected for pregnant and lactating women at mid point.

Consumption and adherence

Consumption was measured by counting empty sachets and was assessed at mid point (after 15 d of use) and endline (after 30 d of use); results are summarized in Table 4. It was found that median sachet consumption by children receiving the LNS was fifteen and thirty sachets by the mid-point and end visits, respectively. Children receiving MNP consumed thirteen and twenty-three sachets, and pregnant and lactating women consumed eleven and twenty-five sachets at mid point and endline, respectively. As shown in Table 4, consumption of LNS was higher than consumption of MNP by either children or pregnant and lactating women at both time points (P<0·001). No differences in consumption of MNP were seen between children and pregnant and lactating women. It was found that 61·9 % (75/121) of the children receiving the LNS consumed all thirty sachets, whereas only 13·0 % (14/108) of the children and 12·1 % (13/107) of the pregnant and lactating women receiving MNP consumed all thirty sachets. ‘Good’ adherence at the mid point of the test was observed in more children receiving the LNS, 89·1 % compared with 65·8 % and 57·0 % of children and pregnant and lactating women receiving MNP (P<0·001).

Table 4 Product consumption at mid point (after 15 d of use) and endline of the 30 d assessment, and adherence at mid point, among the quantitative study sample, Saharawi refugee camps, Algeria, August–October 2009

LNS, lipid-based nutrient supplement; MNP, micronutrient powder; IQR, interquartile range.

Adherence categories were defined using the percentage of actual consumption compared with the recommended dose: poor, <25 % or >125 %; moderate, 25 % to <75 %; good, 75 % to 125 %.

* Sachet consumption higher at mid point compared with other groups at the same time point (P<0·001).

† Sachet consumption higher at endline compared with other groups at the same time point (P<0·001).

‡ Adherence differs compared with other groups (P<0·001).

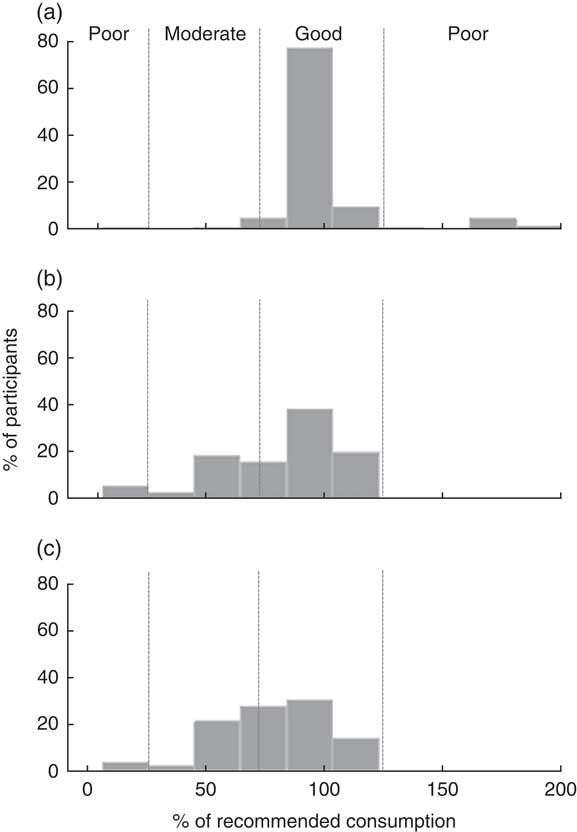

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of percentage consumption for the two different products after 15 d. The median level of consumption with LNS lies close to 100 % and has a relatively narrow interquartile range, although there are a number of outliers. The consumption of seven out of 110 participants receiving the LNS was over 150 % of the recommended dose. Consumption of daily doses of MNP was lower in both children and pregnant and lactating women, and ‘excessive’ consumption was not found in any of these groups.

Fig. 1 The distribution of percentage consumption of the recommended dose for the two different products at mid point (after 15 d of use) among children aged 6–59 months and pregnant or lactating women, Saharawi refugee camps, Algeria, August–October 2009: (a) lipid-based nutrient supplement (LNS) among children; (b) micronutrient powder (MNP) among children; and (c) MNP among pregnant and lactating women. Adherence categories are indicated by dotted lines and the labels on (a): poor, <25 % or >125 %; moderate, 25 % to <75 %; good, 75 % to 125 %

Questions were asked about whether any empty sachets were lost or thrown away and if any sachets were shared. The empty sachets lost or thrown away were classified as not having been consumed for the adherence analysis presented in Table 4. The percentage of participants reporting losing or throwing away empty sachets increased for both nutrition products from the mid point to the end of the test. In the LNS group, 7·9 % (9/114) and 20·8 % (25/120) of caregivers reported having lost or thrown away empty sachets at mid point and endline, respectively. In the child MNP group, 34·1 % (28/82) and 45·4 % (49/108) of caregivers reported having lost or thrown away empty sachets at mid point and endline, respectively. Finally, in the women MNP group, 20·9 % (18/86) and 42·1 % (45/107) of respondents said they had lost or thrown empty sachets at mid point and endline, respectively. Overall, there were higher percentages of participants reporting losing or throwing out empty sachets in the MNP groups compared with the LNS group. A similar proportion of caregivers (<10 %) giving LNS or MNP to their child reported sharing the products with people other than the targeted children (Table 3). However, a very small percentage of pregnant and lactating women reported sharing MNP sachets (<2 %) at the end of the test.

Caregivers and women were given information on the importance of keeping the products in a cool and dry place, and inside a small bag. Direct observations in the home by the study teams revealed the majority of participants stored the product as recommended; for example, in the pantry, wardrobe or in the bedroom.

Qualitative findings on product acceptability

Information on the perceptions and preferences of participants and the community was gathered through focus group discussions. A list of the groups that were conducted is presented in Table 5 and a summary of the main findings is provided in Table 6.

Table 5 Location, product focus and participants of focus group discussions on acceptability, Saharawi refugee camps, Algeria, August–October 2009

MNP, micronutrient powder; LNS, lipid-based nutrient supplement.

Values in parentheses indicate number of participants in a single focus group discussion.

Table 6 Key focus group findings by theme, Saharawi refugee camps, Algeria, August–October 2009

LNS, lipid-based nutrient supplement; MNP, micronutrient powder.

The organization of the mealtime within the household was found to be quite similar in all of the four camps. Two superstitions about the foods were identified that might have affected product acceptability and adherence. However, a direct relationship between these beliefs and product acceptability was not described. Regarding the acceptability of the nutritional products, some of the general comments made included: ‘We like it because it is good for our children’s health and for ourselves’. Two different types of reaction were reported by caregivers regarding sharing. Some caregivers explained to the older children that the product was like a ‘medicine’ for his or her brother or sister and it was not possible to share it, while other caregivers were happy to share the sachets with the siblings. A few people who reported a change in colour of the food when mixed with MNP reported that, ‘The colour of the food changed to yellowish’. In addition, some mothers mentioned that the smell of the MNP was similar to iron. Several adverse side-effects were reported to occur by participants, but none were confirmed by health staff. The occurrence of all adverse effects was found to be low except for changes in stool colour that were reported by many caregivers or family members taking care of the enrolled child. There were several perceived benefits reported for children and pregnant and lactating women. Some community members who were reluctant to accept the products highlighted that the solution to the nutritional problems should be addressed by providing a better general food distribution through a more diversified diet and to avoid using them as an ‘experimental laboratory’. Even so, these more reluctant minorities did not refuse to try the new products and to support their acceptability. In addition, some women believed the best food for them and their children to prevent malnutrition are natural products, the ones ‘inside the cooking pot and should be cooked’. However, it was noted that a product that is introduced by health staff through the Ministry of Health, followed by a sensitization programme, is more likely to be accepted by the population. Clinics were identified as the best locations for product distribution. A long-term distribution of nutrition products to children from 6 months to 59 months of age was not seen as a problem. The women interviewed mentioned that in the kitchen, they are completely free to prepare what they think is necessary and convenient for their children. However, in Saharawi families, elderly people play a very important role, and their opinion is considered as a reference and is always taken into account in decision making. It was stated that grandmothers can especially influence the behaviour of women (young mothers and pregnant and lactating women). Husbands and men also play an important influential role in the community. Both these groups might therefore potentially influence decisions on product use.

Naming and packaging of the products

The focus group discussion participants were asked to provide their opinion on potential names and packaging for the products based on their experience of using or seeing the generic packages of both products. The name proposed by health staff for the LNS was ‘Gazela’, meaning gazelle and metaphorically representing vitality, agility and beauty. The name proposed for the MNP was ‘Chaila’, which is a female camel that provides milk and is considered a symbol of healing of any disease. There is a belief among the Saharawi population that when someone is ill, the person should go with a female camel to the desert during 40 d and take her milk to recover. It was suggested that the name and wording on the packaging for both products should be written in the Arab (Hassaniya) language. It was mentioned that to avoid the risk of superstition or rumours about either products, the composition of the product, including a specification that it did not contain pork, should be written on the package. Colours were also proposed for the packaging and this information was used by an artist who was subsequently asked to design the package.

Discussion and recommendations

The present paper describes a simple and rapid method for determining the acceptability, consumption and adherence to novel nutritional products. This is the first report of an adherence study conducted within a refugee emergency nutrition programme and it proposes thresholds for defining adequate acceptability and adherence for similar products in these contexts. Unlike other recently reported adherence studies( Reference Adu-Afarwuah, Lartey and Zeilani 12 , Reference Hess, Bado and Aaron 13 , Reference Ashorn, Alho and Arimond 21 ), the method is designed to allow the measurement of both under- and overconsumption during feeding at home and calculates adherence taking both of these behaviours in to account. When assessing the use of highly fortified products, such as those we tested, the ability to measure overconsumption is particularly important. The method is most easily applied when the products are supplied in sachets or packets but can be adapted to measure consumption and adherence to products supplied in other formats.

Results indicated that both LNS and the MNP were acceptable to the Saharawi refugees in the camps in Algeria, according to these predefined criteria. While it should be noted that the products were tested on different age groups, there were significant differences in the acceptability and adherence to the products, with LNS performing better than MNP.

Overall, the local population was very aware of the nutrition problems that children and pregnant and lactating women face, such as anaemia and chronic malnutrition, and was willing to cooperate in finding solutions. The fact that several years ago (1999) a similar high-nutrient-density spread product had been trialled and well received may have favoured a positive reaction from the community( Reference Lopriore, Guidoum and Briend 2 ). However, we also found a small proportion of the community who would rather see the nutritional problems being addressed without the use of special nutrition products.

Similarly to the results from our study, other studies have found Nutributter® and MNP to be acceptable to children and caregivers( Reference Hess, Bado and Aaron 13 , Reference Christofides, Asante and Schauer 22 – Reference Tripp, Perrine and de Campos 25 ). It is important to recognize that the acceptability test described here differs from some other, more detailed, acceptability trials. Such trials usually involve testing the acceptability of various products in comparison to one another with a target group of potential consumers or patients. They frequently follow the format of a randomized, controlled, cross-over trial design where food intake, flavour, appearance, colour, aroma preference, overall degree of liking and side-effects are studied. The assessment described here was not intended for comparing the acceptability of different products, but rather to determine if the products were acceptable in comparison to predetermined adequacy criteria.

Acceptability and consumption were measured by household-level interviews and counting empty sachets over a 30 d period. While changes in acceptability and consumption may occur during subsequent time periods, the choice of 30 d was considered an appropriate compromise between the need to allow participants to settle into an established behaviour and the necessity of conducting a rapid assessment within an emergency feeding programme.

Sachet counting revealed that ‘good’ adherence was higher in participants consuming LNS compared with MNP. However, there were a number of outliers with high consumption, raising concerns about the possibility of overconsumption in some young children. A recent study in Burkina Faso has indicated that estimates of LNS consumption may vary according to the methods used, with direct observation during a 12 h period producing lower estimates than overall sachet counting( Reference Abbeddou, Hess and Jimenez 14 ). Despite sachet counting being an indirect method of measuring consumption, it was the most feasible to do in this context as it was not possible for the health workers to undertake direct observation due to time constraints. It also has the advantage of reducing possible bias due to the observer effect. For the calculation of consumption it was assumed that the entire contents of the empty sachet had been added to food and fed to the child or eaten by the pregnant and lactating woman, and that the food was not shared with any other family member throughout the entire intervention.

According to the results of the acceptability questionnaire some sharing did take place, although it was reported by less than 10 % of participants for all products and time points. In addition, some empty sachets were reported to be lost or thrown away and these were assumed not to have been consumed, and therefore adherence might be underestimated. Many participants mentioned a change in stool colour during the consumption test but it did not seem to be a major problem for them as they had been informed in advance that this could happen.

The following recommendations for programme planning and implementation were made based on the results. Concerning the MNP intervention, even though the daily regimen was reported to be acceptable by the participants (for use in both children and pregnant and lactating women), ‘good’ adherence was relatively low. Therefore, in an attempt to improve adherence, a flexible approach (i.e. one sachet every other day) was recommended for programme implementation, instead of a daily regimen. Concerning the usage of the LNS, according to the data collected, caregivers were highly adherent to the daily regimen. However, because the LNS had not been used for periods longer than 6 months in young children in any published trial and the programme was planned to last for much longer in the Algeria camps, a flexible approach (i.e. one sachet every other day) was also recommended, with the view of reducing the quantities consumed over prolonged periods. It was recommended that issues regarding the potential for overconsumption of the product due to its pleasant taste, possible displacement of breast-feeding (especially in the age group 6–12 months) and possible threats to dental health (high sugar content of the product) were to be communicated to the caregivers as part of the key messages communicated to programme participants. It was also recommended that the micronutrient formulation of both the LNS and MNP should not contain iodine due to published data and local concerns on excessive intakes in this population( Reference Seal, Creeke and Gnat 19 , Reference Henjum, Barikmo and Gjerlaug 26 ).

When new nutrition products are introduced in the Ministry of Health programmes in the present refugee context, key staff from the health centres should be sensitized and involved in the whole process from planning to implementation. In addition, experience has shown that a sensitization campaign should be set up at the beginning of any new programme. It was recommended to do regular education sessions with the Ministry of Health involvement via posters, television or radio. These would explain how to use the different nutrition products focusing on the mothers and the grandmothers, what the benefits of the products are, what the potential side-effects are and how to manage them, and information provided to discourage people from sharing. The interventions were recommended to be implemented using a phased-in approach, starting first with some selected sections of the camps in order to develop lessons learnt, rather than launching the programme at full scale from the beginning. Household visits were recommended to be organized in order to monitor the interventions following a specific sampling procedure.

A major limitation of the present study is the large number of missing data from the household interviews, especially in the MNP group, mainly due to forgetfulness of the data collection teams. This was the first acceptability test conducted using this newly developed protocol in a refugee context and, with the benefit of hindsight, a higher level of team supervision from the outset would have been useful. Additionally, half of the acceptability test was conducted during Ramadan when staff can tire more easily during the day. Ramadan may have also influenced adherence negatively for the MNP group. One team was chosen from each clinic (twenty-six teams in total), which was perceived to be very positive because the health staff were involved from the beginning of the test; however, having such a large number of teams made supervision more challenging. Because the LNS test was conducted following the MNP test, the lessons learnt regarding data completeness during the MNP test were taken into account for the LNS test. For the latter, supervision was strengthened thereby decreasing considerably the amount of missing data in the LNS group compared with the MNP group. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants and this may have introduced some bias into the assessment results, as willingness to participate may be associated with a higher probability of adherence to the intervention.

This acceptability and adherence test was the first field study of this type to be carried out by UNHCR as part of its global strategy aimed at reducing anaemia and chronic malnutrition. After the experience gained during this assessment, UNHCR carried out additional acceptability tests in different settings, including Djibouti in November 2009 and Yemen in November 2010. Subsequently, Operational Guidance was published in 2011 containing a field-friendly, generic acceptability test protocol that was designed to be adapted to each setting( Reference Style, Tondeur and Wilkinson 27 ). The LNS and MNP blanket programmes started in the camps in Algeria in December 2010 using some of the recommendations described here, and the impact results on anaemia and nutritional status in children aged 6–59 months from the routine cross-sectional surveys and programme monitoring data will be analysed and published in the future.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge the contribution of the field teams, the Saharawi community and the Saharawi Ministry of Health in the implementation of this study. Financial support: This research was supported by UNHCR. Conflict of interest: Samples of micronutrient powder and lipid nutrient supplement were supplied free of charge by the manufacturer. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose. Authorship: All authors contributed to the conception and design of study; U.N.S. collected the data; U.N.S., M.C.T. and A.J.S. conducted the analyses; U.N.S., M.C.T., C.W. and A.J.S. interpreted the data; U.N.S. and M.C.T. drafted the article; A.J.S., C.W. and P.S. revised the article; all authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The Saharawi Ministry of Health approved the implementation of the study and the Ministry of Health authorized the assessment. The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all potential participants signed an informed consent form.