Background and rationale for the development

It is difficult to assess the extent of the prevalence of mental health disorders in primary care because of difficulties related to their classification (Gray, Reference Gray1988). According to Goldberg and Huxley (Reference Goldberg and Huxley1992), 23% of the general British population experience mental health problems, 76% will visit a general practitioner (GP) and 44% will be appropriately diagnosed. In spite of the constant increase in demographics, these percentages remain unchanged (National Health Service Information Centre, 2007). There has been, however, an increase in the prevalence of common mental disorders in women from 19% in 1993 to 21.5% in 2007 (National Health Service Information Centre, 2007). The current economic climate has also been reported as a cause for the further deterioration in the mental health of the UK’s population (Mental Health Foundation, 2009). The King’s Fund (2009) has reported that the mental health services in the UK will be used in 2010 by 1.32 million people more than in 2007, as based on demographic data alone, with an additional cost of £10.09 billion.

The demand for counselling services in primary care settings is therefore rising, implying a potential increase in the cost of service provision. In an attempt to address the demand for services in general practice we developed an economically realistic model for the delivery of psychological therapy delivered by trainee counsellors under supervision.

In the UK, 76% of patients referred by GPs to regulated counsellors from the British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP, 2002) had what were defined as ‘clinical’ problems requiring counselling therapy (Mellor-Clark et al., Reference Mellor-Clark, Rowland and Bower2001). According to the BACP website, counselling is ‘a systematic process which gives individuals an opportunity to explore, discover and clarify ways of living more resourcefully, with a greater sense of wellbeing’. Counselling may be concerned with addressing and resolving specific problems, making decisions, coping with crises, working through conflict, or improving relationships with others (Department of Health, 2001).

Traditionally, counselling services in general practice have been delivered mainly by GPs, or professional counsellors (either voluntary or private). There has been some growing debate as to whether general practice registrars would benefit from doing psychiatry placements (Ratcliffe et al., Reference Ratcliffe, Gask, Creed and Lewis1999). It has however been reported that the current psychiatry tools available to GPs do not translate into a 10 min consultation (Hodges et al., Reference Hodges, Inch and Silver2001), with 20% of GP patients remaining undiagnosed (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Bennewith, Lewis and Sharp2002; Verhaak et al., Reference Verhaak, Prins, Spreeuwenberg, Draisma, van Balkom, Bensing, Laurant, van Marwijk, Van der Meer and Pennix2009). There is no specific evidence-based treatment for all patients seeking counselling and this poses restrictions in the effective and efficient use of the GP’s time. Referrals to mental health specialists have been due to patients requiring counselling and GPs seeking clarification of diagnosis (Alexander and Fraser, Reference Alexander and Fraser2008). In their systematic review of the literature, Bower and Rowland (Reference Bower and Rowland2006) have shown that patients are more satisfied by having treatment with a counsellor than with a GP. The research base for the effectiveness of GP counselling interventions remains contradictory and confusing. Huibers et al. (Reference Huibers, Beurskens, Bleijenberg and van Schayck2007) produced a systematic review of the literature to show that psychosocial interventions seem to be more effective in primary care than in usual GP care.

There are many other primary healthcare professionals currently involved in some form of counselling services in the UK including health visitors and community psychiatric nurses. Research with patients showed that they are more satisfied with formal counselling in primary care than with GP care alone (Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Corney and Fitzgerald2000), even if only related to the amount of time spent with the counsellor as opposed to the GP. Counsellors have been therefore increasingly employed in England, where 9000 practices employed counsellors by 2001 (Mellor-Clark et al., Reference Mellor-Clark, Rowland and Bower2001), and there are many models by which counselling is provided which, in large part, depend on the nature of the community service provider for the practice.

There is an absence of co-ordinated funding or support for primary care counselling within the National Health Service (NHS) and provision varies in quality and extent depending on area. The cost of counselling is a significant factor when set against procedures such as heart surgery for which funding competition exists. Counselling in primary care may consequently be provided through volunteer groups or private funding. In general, counselling is associated with increased costs (Friedli et al., Reference Friedli, King and Lloyd2000), hence the dilemma for many practices lies in finding an effective model for counselling within the practice. In fact, counsellors working in primary care may reduce the overall cost of care by causing a decrease in the number of referrals to psychiatrists, and ordering fewer prescriptions (Bower et al., Reference Bower, Byford, Sibbald, Ward, King, Lloyd and Gabbay2000).

Our model supports the provision of counselling in general practice settings delivered by trainee counsellors under supervision. We present some preliminary qualitative findings exploring perceptions about the model from the supervisor, the practice co-ordinator and GPs. In these preliminary findings, the perceived patient outcomes achieved include alleviation from symptoms of anxiety and improved behavioural patterns.

The introduction of the new White Paper Trust, Assurance and Safety (Department of Health, 2007), has meant that each healthcare counsellor should be supported through membership of an appropriate professional body. The BACP, for example, has recommended that counselling should be provided by counsellors that have completed a Diploma course comprising of 450 h training and it should include a substantial amount of time spent in a work-base learning environment. Trainees on counselling courses are encouraged to join a professional body as student members.

Developing in-house counselling services

The GP surgery offering the counselling services lies in an area of medium local social deprivation and deals with an average of one to three depressed or anxious patients a day per GP. This makes a total of about 10% of the consultations per GP. Overall, about 30% to 50% of the patients seen have some psychological element within their consultation. The GP surgery has never received funding for NHS counselling and has always depended on volunteer services within the local area or on the ability of patients to self-fund private counselling. It was, however, felt that volunteer services using a listening approach to therapy did not always meet the expectations and needs of patients. This limited counselling support meant that most patients were managed mainly by brief GP support and medication. The surgery therefore developed an approach for providing in-house counselling through the collaboration with higher education (HE) establishments to form partnerships with surgeries as work placements for trainees undertaking a Diploma in Counselling or similar course accredited by the BACP. HE establishments have partnerships with voluntary organisations, hospitals, GP centres, schools, large organisations providing counselling support for employees, police, statutory, and the private sector.

The surgery as an HE partnership for training counsellors

A new model for counselling was proposed based on four volunteer trainee counsellors. The trainees studying in the local area are able to fulfill the requirement of the training course by gaining hands-on experience at the practice. The Diploma in Counselling comprises of one theoretical year and one year of work-based placement. Trainees obtain a certificate after the completion of the first year of training and are already student members of a professional body, becoming accredited members after completing 100 h of counselling under supervision (BACP regulation) which means that this often happens whilst in their placements.

The BACP requires regular practice based support from an experienced counsellor as well as access to a HE tutor for support. The regular supervision received from an experienced colleague is often funded by the trainees. The partners at the GP surgery decided to set aside surgery funding to support the clinical supervision of students by an experienced counsellor.

The in-house counselling referral system

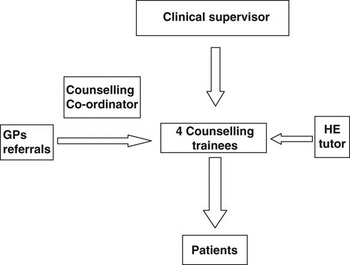

GPs are required to specify the type of problem referred on a standard referral form. Problems that are outside the scope of counsellors such as psychotic depression or suicidal risk are discussed between the counselling co-ordinator and the GP for psychiatric referral. The GP in-house referrals are carefully monitored by the counselling co-ordinator who grades and prioritises them accordingly. The clinical supervisor allocates patients to trainees according to their learning plans, which are revised once a month. The model is a six weekly session model using cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) only focused on one or two specific problems that the patient identified as the key issues. It uses four counselling trainees that alternate ensuring a gender mix on different days of the week so that only two trainees are made available each day. Over a year the trainees see on average two to three patients per week and then offer six additional sessions of therapy per patient. The model involves a clinical supervisor, a counselling co-ordinator, four trainees in-house and an outside HE tutor (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Diagram of the Counselling Model

The role of the clinical supervisor

The clinical supervisor acts as a link between the HE tutor and the trainee whilst on placement. He/she meets each trainee for 2 h every month and must produce reports on the performance of each trainee by the end of the trainees’ placement. It is their role to provide regular support for the trainees and be easily accessible at all times. This has meant that the clinical supervisor may be accessed by trainees on a 24 h basis as a risk management measure. Potential trainees are initially interviewed to assess their level of performance and professional judgement. During the interview the supervisor evaluates each trainee’s learning needs by discussing factual case scenarios to produce an individual learning plan. The trainees are also inducted into the practice and the counselling system.

The role of the counselling co-ordinator

One of the initial student counsellors assumed an in-house counsellor co-ordinating role in return for use of the premises as part of their own private counselling practice. The in-house counselling co-ordinator administers bookings, referrals from GPs and so forth, and ensures that BACP’s requirements for training are satisfied. The co-ordinator liaises with a GP representative, the practice manager and the administration staff to check that the referral protocols from GPs are appropriate. In contrast to the clinical supervisor, the co-ordinator is based on the premises.

The trainee counsellors

Trainee counsellors provide feedback on the patients, write discharge letters and make brief additions to patient records. The trainees must also submit reports to the University on their work-based experience. The practice provides primary care-focused training and a reliable, supportive placement that achieves both service commitment and training requirements.

Cost of the model

Only the clinical supervisor is funded by the doctors. The service has been operating on a budget of £17.50 per week (£840/annum) excluding stationery costs and the potential loss of income from room rental for one day a week (£100/week). There was no reimbursement of these costs by the primary care trust (PCT) overseeing the practice. Although the service commitment offered by the trainees is on a voluntary basis, it is a requirement for the successful completion of the Counselling Diploma and in line with the regulatory guidelines of the BACP. Thus there were benefits for all members of the counselling team. For the doctors there was a small reduction in personal income of approximately £100/annum offset against what was perceived as a benefit to patients and a potential reduction in consultation length.

Service achievements

This service has been in place for four years at the practice and has processed 36 referrals (200 h) per year (£23 per patient and £4.20 per hour). The feedback from the HE trainee providers, the trainees, the GPs in the practice, the patients and expert counsellors has been very positive with respect to the counselling benefits. Most trainee counsellors have found the experience to be of great value and most requested to stay on for a short period until they had established regular work. The patient dropout rate is low once the patient had started in counselling. The main issue has been the waiting time to start counselling. The service has been perceived as a victim of its own success and demand has exceeded the counselling hours available. Waiting lists for counselling are currently between three to twelve weeks long. Information on when a patient is going to be seen is made available to all GPs in the practice. GPs have responded by reducing the number of referrals at periods of long wait. Hence the wait rarely exceeds three months. Reinforcing the model of six weekly sessions per patient did ensure no patients remained in the system and blocked further referrals.

Preliminary findings from the evaluation

All members of the primary care team reported benefits from the counselling in terms of improved support for patients and less demand for intervention and appointments with GPs. Our preliminary results from the counselling service were based on a small-scale qualitative study that explored perceptions about the model with respect to achieved patient outcomes. The qualitative study was designed as an internal audit and was carried out by a researcher from NHS Education South Central. Patients were not involved in this preliminary evaluation. GPs were asked instead to provide an opinion on the perceived patient outcomes achieved by the model. Ethical approval was therefore not required. The preliminary results presented in this study are from a focus group with GPs, and interviews with GPs, the practice counsellor, and the trainees’ supervisor. We are in the process of obtaining further qualitative and quantitative data from patients using the core performance indicators that measure specific patient outcomes resulting from psychological therapy (Mellor-Clark et al., Reference Mellor-Clark, Rowland and Bower2001).

The service was reported to be of benefit to patients for a variety of reasons. First of all, it is seen as a free in-house service that provides a safe environment for counselling at a local level. GPs believe that patients concerned to maintain confidentiality about using the counselling service may justify going to the surgery without providing an explanation. There was also a reported decrease in the amount of prescriptions written for patients with stress, anxiety and depression that will be quantified further as part of a large scale evaluation. The service was also perceived to act as a preventative measure for some patients. GPs also experienced some alleviation in pressure regarding working with borderline cases as illustrated by the following comment about the referral of patients who claimed to be suicidal:

‘(I)…… referred (him/her) to the emergency services, they bounced (him/her) back saying the patient was not suicidal enough and got the (in-house) counselling service to support the patient… (who) is far more settled and improved…’ (GP; 1M)

Other reported achievements included a reduction of intrusive and anxious thoughts, and the reduction of anxiety symptoms with behaviour activation. It also met the demands of the trainees’ learning requirements (100 h of practice). Trainees received on-the-job supervision, which provided them with a practice base for future employment.

Nevertheless, there were concerns over counselling waiting time as demand exceeded capacity. The service should not be seen as an alternative to acute psychiatric treatments and GPs must be able to judge the severity of the cases that are referred to the counselling service, although all referrals are double-checked by the supervisor.

Discussion and limitations

There are a number of counselling models reported in the literature. These depend mainly on the use of different counselling techniques specific for general practice. In London, for example, counsellors based in general practices have been reported to use the Rogerian model for counselling using 1 to 12 sessions in 12 weeks (Friedli et al., Reference Friedli, King and Lloyd2000). Current models for the delivery of counselling within a general practice setting use either GPs or counsellors. Counsellors may provide private care in general practices or be part of the practice team or provide counselling services on a rotational basis to patients referred to by GPs on behalf of a PCT (Greasley and Small, Reference Greasley and Small2005). The literature shows that employing a counsellor in a practice can be expensive as calculated by the number of patients seen over a period of nine months (Friedli et al., Reference Friedli, King and Lloyd2000). There is, therefore, a need to explore different forms of delivery for counselling services in primary care.

The rise in demand for counselling services in primary care has instigated the recent development of the telephone counselling service in the US that uses CBT and motivational interviewing techniques at a low cost (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Emiliozzi, Waters and El Hajj2008). There has also been an increase in the number of established self-help clinics in the UK that are supported by paraprofessional mental health workers (Farrand et al., Reference Farrand, Confue, Byng and Shaw2009). PHASE is an interesting health technology programme delivered in practices by practice nurses that is based on the self-help guide for patients produced by the Mental Health Foundation for common mental disorders found to be fit for delivering self-help mental care (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Richards, Barham and Cahill2002). This community-based counselling model for primary care has been compared in efficiency to a model of delivery that uses mental health registered nurses with the conclusion that it may not be viable for patients requiring long term support. Other models include the use of home clinical programmes delivered by mental health registered nurses (Blacklock, Reference Blacklock2006).

The model we present depends on a supply and demand for work-based training placements for counselling students in the local area. Although it currently feeds from trainees on the Counselling Diploma course, it would be possible to recruit trainees from BA or MSc counselling or psychotherapy courses. It is stipulated that trainees are registered with an adequate professional body at a graduate level.

The difficulties encountered in setting up the model in the practice were mainly logistic and included providing a dedicated room for counselling services that would offer an adequate environment to support trainees. There was also a need for the supervisor to develop in-house protocols for managing risk and managing the referral system (Dunkley, Reference Dunkley2006, Reference Dunkley2007). Once the model was set up it was found that not all patients were able to keep their appointments. It was therefore necessary to establish a patient contact system by phone to help reduce waiting lists. The model is quality assured through the supervision of trainees, the development and co-ordination of protocols, and regular feedback between the colleges and the practice as well as between patients and their GPs.

There were benefits to all members for the counselling model but it remains dependant on the good will and support of the individual counsellors and particularly the counselling co-ordinator and counselling supervisor. There is a balance between time invested and benefits, which can be easily disrupted and needs a regular review.

The in-house counselling model is transferable to other general practices and the benefits to individual members of the team are dependant on local circumstances. The doctors need to be prepared to accept a potential reduction in income to fund the service or need to lobby the primary care organisations to provide the modest amount of funding required. Within this practice there was capacity to provide room use in exchange for remuneration, which helped to offset the costs. There is also a need to provide a space within the practice to accommodate the counselling service.

It is important that GPs also have a clear understanding of a counselling service’s limitations in the treatment of patients. There is a need to ensure and maintain links with HE and colleges that provide the courses accredited by the BACP or other relevant professional body.

In the future it is hoped to expand this service provision within the area and to provide a more focused service, depending on the needs of the patients, through the formation of, for example, an anxiety group, or a self-esteem group.

Conclusion

Over the last five years there has been a growing need for psychological counselling exempt of medication in the local area. Despite absence of NHS funding a much-needed counselling model has been established in the surgery. There is very little information in the literature on cost-effective counselling provision in GP surgeries. We have shown that this model can be cheap, has been running for four years without any major problems or complaints from patients and provides a safe learning environment for trainees under supervision. It should be noted that the initial screening of trainees’ learning needs during their interview is one of the factors in the success of the scheme, as well as the supervision received from a competent counsellor and in-house co-ordination of the scheme. There has been no trainee dropouts on the placement and all trainees on placements at the practice have successfully completed their Diploma course. Primary care organisations should consider funding such a model of general practice based counselling as it is a low-cost model when compared with direct funding of counsellors at approximately £40 per hour.