Recent purges in the Chinese political elite provide strong evidence that factional affiliations continue to be a central organizing principle in the largest authoritarian regime in the world. However, it remains a matter of anecdotal observation how various leaders in the party have recruited their factions. Faction is defined here as a set of mutually beneficial ties between multiple clients and a patron which aim at maximizing the patron's power. As Pye put it long ago, factions are “… personal relationships of individuals who, operating in a hierarchical context, create linkage networks that extend upward in support of particular leaders who are, in turn, looking for followers to ensure their power” (Pye Reference Pye1981, 7).

Guided by the qualitative literature on faction, we seek to examine how reform era leaders in China have formed their factions. We first derive four reasonable ways of measuring factional ties. We then evaluate which measure of faction predicted the promotion of clients in various factions to full Central Committee membership during party congresses where the patron was either the incumbent or the out-going incumbent party secretary general. Our results show Hu Yaobang, Jiang Zemin, and Xi Jinping recruited faction members who shared native place, school, and work ties with them. Hu Jintao, in contrast, recruited faction members primarily from among previous work colleagues, especially from the early stage of his career.

Our findings suggest that different secretary generals likely had slightly varying styles of forming factions, which cautions analysts against perceiving factions as being based on a particular type of ties. An overly broad definition of factional ties, however, likely will produce more measurement errors than more restrictive definitions of factions. These errors will bias the estimates downward and increase the standard errors in most cases. Also, among three measurements of workplace-based factional ties, the most restrictive definition seems to generate the least measurement errors and the most consistent predictions.

In addition, our analysis identifies two ways in which formal institutions have impacted factional politics. First, the reserve cadre system first launched in the 1980s allowed even deposed party secretary generals to have an impact on the promotion of alternate Central Committee (ACC) members to the full Central Committee (CC). Second, the retirement rule for ministerial cadres likely gave rise to a cohort effect in faction-based promotions. That is, a patron is more likely to exert an influence on lower-level promotions of his clients when he first becomes a secretary general than toward the end of his tenure, because his contemporaries will have become too old for lower-level promotions. These two institutional effects lend support to Nathan's hypothesis that formal institutions in the party constitute “…. a kind of trellis upon which the complex faction is able to extend its own informal, personal loyalties and relations.” (Nathan Reference Nathan1973, 44)

THE BASIS OF FACTIONS

As earlier generations of China scholars had observed, patron–client relationships developed over the course of a patron's career served as platforms whereby regime goods such as promotions and money for the clients were exchanged for political support for the patron (Dittmer and Wu Reference Dittmer and Wu1995; Pye Reference Pye1981). Due to the highly opaque nature of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), it was very difficult to establish whether factional ties played a role in key outcomes in the regime, including promotions and purges of top officials, as well as major policy changes.

Nathan (Reference Nathan1973) observed that internal political conflicts provided a glimpse of the shape of a faction because the systematic removal of officials in a senior leader's patron–client network was a sure way of destroying a faction. For example, after the first few months of the Cultural Revolution, scholars learned that the Cultural Revolution targeted Liu Shaoqi because almost all of those who had worked with Liu in the CCP Northern Bureau in the 1930s and 40s became victims of purges. Scores of Northern Bureau cadres, including Peng Zhen, Bo Yibo, Liu Lantao, and An Ziwen, were labeled as capitalist roaders and purged from their positions (Gao Reference Gao2003, 219). In fact, an entire subsection of the inquisitor organization, the Central Case Examination Group, was dedicated to “investigating” Northern Bureau or “white area” cadres (MacFarquhar and Schoenhals Reference MacFarquhar and Schoenhals2006, 283). Similarly, when the Chinese military arrested four legally elected Politburo and Politburo Standing Committee members in 1976, their followers, including Wang Xiuzhen and Xu Jingxian, were arrested (Perry and Li Reference Perry and Li1997, 185). Hundreds, if not thousands, of followers of the “Gang of Four” were subsequently removed from their positions, and some put in jail (Ye Reference Ye2009, 1360).

In the reform period, such wholesale purges seemingly came to an end. When Hu Yaobang was demoted from his general secretary post, few were affected (Baum Reference Baum1994, 206). Even when Zhao Ziyang was arrested for siding with the students in 1989, only a handful of close aides got into trouble. Sympathizers like Hu Qiuli were demoted but remained in the upper echelon of the party (Lam Reference Lam1995, 163). The absence of large-scale purges led some observers to conclude that the role of factions in Chinese politics had weakened in recent years. In place of factional politics, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has shifted toward institutionalized politics where the interests of formal institutions superseded patron–client relationships (Miller Reference Miller and Li2008; Bo Reference Bo, Naughton and Yang2004b). Furthermore, on questions of cadre promotion and removal, formal procedures and established rules had sidelined personal relationships (Bo Reference Bo, Naughton and Yang2004b; Huang Reference Huang and Li2008).

These conclusions turned out to be premature. Through the seemingly stilted politics of the 2000s, three rising stars at the time, Zhou Yongkang, Ling Jihua, and Xu Caihou, had been building personal empires which involved both systematic promotions of trusted followers and collaboration with selected groups of businesspeople to amass vast fortunes. Xi Jinping's anti-corruption drive has led to the systematic uprooting of these three figures and their followers, thus allowing outside observers to map these factions. In the case of Zhou Yongkang, he systematically promoted colleagues from earlier stages of his career into important positions once he had entered the Politburo Standing Committee. From 1968 to 1998, Zhou worked in China's oil sector, in units that ultimately became state-owned oil giant PetroChina. Former PetroChina colleague Jiang Jiemin later became the head of the State Asset Supervision and Administration Committee (SASAC), in charge of all the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China (Downs Reference Downs and Li2008). Other PetroChina colleagues and subordinates, including Wang Yongchun, Wang Shoufu, Li Hualin, and Shen Dingcheng all came to occupy senior positions in PetroChina, making the largest oil company in China essentially a personal fiefdom of Zhou Yongkang (Caixin 2014a). Although Zhou served as Minister of Land and Resources for only one year, his personal secretaries at that time, Ji Wenlin and Guo Yongxiang, later accompanied him to Sichuan and eventually became the vice governor of Hainan and the vice governor of Sichuan respectively (Caixin 2014b). When Zhou was promoted to Sichuan provincial party secretary in 1999, he similarly cultivated ties with colleagues who one-day would occupy important positions in the province and beyond. For example, he promoted Li Chuncheng to the position of party secretary of the provincial capital Chengdu. He also promoted Li Chongxi to the position of Sichuan province vice secretary (Caixin 2014a). Having trusted followers in these positions afforded Zhou some degree of control over Sichuan even after his promotion to the central government.

Interestingly, once Zhou ascended to the apex of power as the secretary of the Law and Politics Committee and Politburo Standing Committee member, he did not cultivate many new followers. After Zhou's own arrest, besides his personal secretaries at the time, only public security vice minister Li Dongsheng was arrested in connection to the Zhou Yongkang case. Li, who had been a TV producer for China Central Television, likely had known Zhou even before his promotion to the Law and Politics Committee, which was in charge of the Ministry of Public Security (Caixin 2014a). Although there were rumors that Public Security Vice Minister Yang Huanning was under investigation, he remains in his position to this day. The recent arrests of senior Ministry of State Security officials, another ministry which had been controlled by Zhou Yongkang, were said to be linked to the Ling Jihua case rather than to Zhou Yongkang (Reporters Reference Reporters2015). In sum, the wholesale arrests of Zhou Yongkang's followers from the early stages of his career revealed that factional politics remains alive and well in China today.

For students of factional politics, the Zhou Yongkang case further suggests that factional ties had been nurtured mainly with Zhou's work colleagues, especially those whom he met in the earlier stages of his career. The literature, however, posits that factions were formed on much broader bases, which include shared native places, schools, and workplaces (Pye Reference Pye1981; Dittmer Reference Dittmer1990; Dittmer and Wu Reference Dittmer and Wu1995; Lieberthal and Oksenberg Reference Lieberthal and Oksenberg1988, 156). Both Soviet and Chinese factions also developed out of common revolutionary experience in various guerilla base areas (Easter Reference Easter1996, 557; Gao Reference Gao2000). Within the party, there is even a term called “mountaintopism” (shantou zhuyi), which refers to various mountains that guerilla commanders, who became senior CCP officials, had once occupied prior to 1949 (Huang Reference Huang2000, 11). The current generation of Chinese leaders formed relationships on the basis of shared experience during the Cultural Revolution. Both Wang Qishan and Xi Jinping, for example, were sent down to communes around Yan'an and saw each other frequently (Wu and Li Reference Wu and Li2013). Other factions emerged among alumni of prestigious universities, such as Tsinghua University (Li Reference Li1994). Given our understanding of factions, researchers can, on the basis of shared attributes and experience between senior and junior officials, map out their potential ties with one another. As Dittmer (Reference Dittmer1995, 12) cautions, however, “an objective basis for an affinity does not necessarily create one.” Because researchers only can infer ties on the basis of observable information, they ultimately cannot observe factional ties with 100 percent accuracy.

Despite such drawbacks, measuring ties according to shared attributes produced remarkably consistent results. When lower-level officials had shared attributes or experience with the formal heads of the CCP, or with powerful figures like Deng Xiaoping, they enjoyed a higher chance of being promoted through the party ranks (Shih et al. Reference Shih, Adolph and Mingxing2012; Jia et al. Reference Jia, Kudamatsu and Seim2014). Keller (Reference Keller2014) finds that connections with a greater number of Politburo members enhanced a Central Committee member's chance of entering the Politburo. Other studies also find that when local governors or even companies had informal connections with senior members of the party, the locality or company would receive larger bank loans or greater profits (Shih Reference Shih2008; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Xu and Zhou2011). In all of these studies, proxies for informal connections are developed and regressed on an important outcome in the party-state. In all of these cases, a significant finding is discovered.

Still, the literature provides little guidance on how individual leaders in the CCP may recruit their factions. Some scholars have observed that, with the passing of the revolutionary generation, contemporary leaders of China tended to cultivate followers from their work places instead of recruiting widely on the basis of other shared ties, such as native and school ties (Huang Reference Huang and Li2008, 84). Nathan also observed that officials in China increasingly became specialized in different policy tasks, which may make members of a faction more dominated by those from a certain bureaucracy (Nathan Reference Nathan2003). Although these trends may be true in general, perhaps those officials with broad-based networks are still most able to obtain the highest positions in the regime.

ASSESSING FACTIONAL TIES OF DIFFERENT LEADERS

In order to discern the evolution of the bases of factions, we investigate whether leaders in the reform era (1978–present) recruited and maintained faction members on a broad basis or merely from among work colleagues. A related question is whether patrons primarily recruited work colleagues in the earlier stages of their careers or throughout their careers. Finally, among work colleagues, we investigate whether the most exclusive definition of factions provides more consistent predictions of the factional effect (Keller Reference Keller2014).

In the following analysis, we use four different measurements of factions to assess how post-1978 party secretary generals in the CCP have recruited their factions. Our four definitions of factions are listed in Table 1. These are all definitions that can track the ties between the party secretary general or party chairman and officials who were alternate members of the Central Committee prior to a party congress. The first definition (Broad Ties) is the most expansive one used in existing literature, which records all native place, school, and work ties accumulated by a party secretary prior to his ascension to the top position (Shih et al. Reference Shih, Shan and Liu2010a; Shih et al. Reference Shih, Adolph and Mingxing2012; Lieberthal and Oksenberg Reference Lieberthal and Oksenberg1988, 156). Because many officials came from populous provinces such as Sichuan and Shandong or attended elite universities such as Peking University or Tsinghua, including native place and school ties may generate too many false positives and weaken the effect of this factional measure.

Table 1 Four Measurements of Factional Ties

The second measurement (Complete Work Ties) records the work ties that patrons accumulated prior to appointment to the party secretary general post. Tracking only work ties accords with Huang's (Reference Huang and Li2008) notion that factions are increasingly based on common work experience in specialized bureaucracies. The Zhou Yongkang case, however, revealed that Zhou had accumulated most of his work ties prior to his entrance into the Politburo, as observed through recent arrests. Thus, the third measurement (Early Work Ties) records only work ties that a patron accumulates prior to his entrance into the Politburo.

Finally, Keller (Reference Keller2014) employs a highly restrictive definition of faction, which records the relationship between a patron and a client only if the client enjoyed a promotion within the same work unit while she worked with the patron. She argues that an expansive definition of political ties would record more ties between senior party leaders and their clients, but would also generate higher numbers of false positives (Type II errors). If factional ties were used to predict the distribution of regime goods, Type II errors, even if distributed randomly, would bias the coefficients toward zero and also increase the standard errors of the estimates (Imai and Yamamoto Reference Imai and Yamamoto2008). Because strictly following this promotion definition results in too few observations for our proposed analysis, we modify this definition slightly. The fourth measurement (Restrictive Work Ties) records factional ties if the client experienced a job rotation (as opposed to promotion) while the patron and the client overlapped in the same work unit prior to the patron entering the Politburo. Rotation here means both a client's rotation into the patron's work unit and an outward rotation from the patron's work unit to another one.

This variable captures two important dynamics commonly observed in factional politics. First, when a senior official was promoted to a new post, he or she typically brought a couple of close associates to the new posting. Zhou Yongkang adhered to this pattern by bringing his personal secretaries from PetroChina and from the Ministry of Land and Resources to Sichuan to serve as senior officials in the province (Caixin 2014a). Second, once a patron became well established in a work unit, he or she at times sent a client to another organ to extend the faction's influence. Hu Jintao, for example, sent many Youth League cadres to vice provincial level positions all over China, which extended the Youth League faction's influence across China (Bo Reference Bo2004a). We further exclude any rotations to the National People's Congress or the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) because these rotations likely represented demotions rather than promotions. The base data come from an updated database on all alternate and full Central Committee members, which is built on the original CC data (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Shih and Lee2015). Unlike the original data by Shih et al. (Reference Shih, Shan and Liu2008), the new data incorporate over 12 years of new information and make numerous corrections from the original data.

In Table 2, we report the share of 11th–18th Party Congress (PC) alternate Central Committee (ACC) members who had ties with the various party chairmen/ party secretary generals (PSGs). We restrict our analysis to ACC members in this article in order to minimize the problem of endogeneity. According to Shirk (Reference Shirk1993), full Central Committee members are the “selectorate” in the CCP because they vote the new Politburo and secretary general into power. ACC members, in contrast, do not have such power and should have minimal impact on the selection of the next secretary general. As such, an individual ACC member's tie with the patron should have minimal impact on the appointment of the patron to the secretary general position, but the patron should be able to exert a great deal of influence over the promotion of the ACC member.

Table 2 The Share of 11th–18th Party Congress Alternate CC Members with Ties to the Party Secretary General, by Ties Measurements

According to Table 2, Broad Ties records ties between 12.12% of the 11th PC ACC members and Hua Guofeng, who was party chairman at the time. As the definition of factional ties grows more restrictive, the share of 11th PC ACC members with Hua ties also fell. Early Work Ties only records 8.3% of 11th PC ACC members as having connections with Hua, and for Restrictive Work Ties, only a measly 3% of the 11th PC ACC members had ties with Hua. Looking at 18th PC, Broad Ties records that 13% of ACC members had ties with Xi Jinping, while Restrictive Work Ties only records 5.8% of ACC with Xi connections, a difference of over 100%. In general, none of the Ties variable records over 20% of ACC members with ties to the secretary general, except for Broad Ties with Jiang Zemin at the 14th Party Congress.

Of note, both Complete Work Ties and Early Work Ties report the same share of ACC as members of Jiang Zemin's faction from the 14th Party Congress onward. The reason for this anomaly is that Jiang was catapulted from a Politburo member directly to party secretary general while serving as the party secretary of Shanghai. There was thus only a two-year gap between his promotion into the Politburo and his appointment to the highest post, and he worked in Shanghai with more or less the same people in this period. Also, for party secretary generals who served past their first term, i.e. Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao, the share of their followers in the alternate Central Committee pool dropped after their first terms, regardless of measurement being used. This likely reflects a cohort effect, which will be discussed more extensively below.

To evaluate the factional recruitment and maintenance strategy of the various party secretary generals, we run a series of logit regressions across the various party congresses, from the 12th to the 18th. Again, to guard against the endogeneity problem, we exclusively examine ACC members rather than full CC members prior to a congress and whether they were promoted to full CC rank after a party congress. Logit models are used to estimate the impact of independent variables on a binary dependent variable, which proxies for an underlying continuous dependent variable (Y*). The lack of promotion may be due to mandatory retirement age, so we exclude any ACC members above the age of 65 in our analysis. Besides the factional variables, we include a series of basic demographic variables which may impact one's chance of promotion, including age, the number of years as a party member, the level of education, gender (1 = female), and ethnicity (1 = minority).

Although we generally expect factional ties with the current or outgoing secretary general to matter for one's chance of promotion, we expect a couple of exceptions. First, although Hua Guofeng was nominally the head of the party until the 1982 12th Party Congress, he had lost his political influence by that point (Baum Reference Baum1994, 132). Therefore, we do not expect ties with Hua Guofeng to exert any influence on ACC promotions at the 12th Party Congress. Another exception was Zhao Ziyang. Although he was elected secretary general prior to the 1987 13th Party Congress, he was only secretary general for a few months before the Congress, and he was purged long before the 14th Party Congress in 1992. Therefore, he may not have had time to exert much influence on any of the party congresses. Otherwise, we expect ties with Hu Yaobang, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Xi Jinping to exert some influence on the promotion of ACC members while they served as secretary generals. They may even have affected ACC promotions in the party congress immediately after their retirement. Again, the key question is whether those who shared birth and school ties with these powerful officials also benefited, and whether work colleagues who got to know these figures later on in their careers benefited.

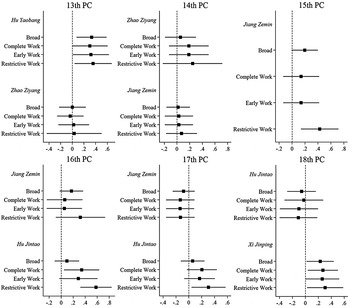

Figure 1 shows that, contrary to the expectation of some scholars, some Chinese leaders continued to recruit faction members on a broad basis, including those with whom they shared birth province and school ties. For the ease of interpretation, all the coefficients have been transformed into marginal effect—the impact on the probability of promotion if the independent variable increases by one unit. For binary independent variables, the coefficients show how much the predicted probabilities of promotion have increased when the variable changes from zero to one. We further include the 90% confidence intervals in horizontal lines around the point estimates. We exclude our findings for the 12th Party Congress in the interest of space and because, surprisingly, neither Hua Guofeng nor Hu Yaobang exerted any influence on ACC to CC promotions at the 12th Party Congress. This outcome is expected for Hua Guofeng. To our surprise, although Hu Yaobang had been active in elite politics for years before his elevation to the secretary general position, none of the ACC members identified as Hu Yaobang followers were promoted from the ACC to the CC at the 12th PC, regardless of which ties measurement we use. In fact, this pattern was so absolute that we could not generate an estimate of the coefficients in any of our models. This may be due to the unique nature of the 12th PC, which saw the rehabilitation of many veteran cadres from older factions cultivated during the Long March period (Shih et al. Reference Shih, Shan, Mingxing, Carlson, Gallagher, Lieberthal and Manion2010b). The rehabilitation of so many veteran cadres likely prevented even Hu Yaobang from exerting too much influence to promote his junior followers.

FIGURE 1 The Marginal Impact of Various Ties with the Former or Current Head of the Party on ACC Member Promotion into the CC: 13th PC to 18th PC (expected values and 90% confidence intervals)

Ties with Hu Yaobang had a markedly different and stronger impact on promotion at the 13th Party Congress. Figure 1 reveals that at the 13th PC, ties with Hu Yaobang increased one's probabilities of being promoted to the CC by 25–40%, compared with an ACC member without ties to Hu Yaobang. For all four ties measures, connections with Hu Yaobang exerted influence on promotion that was significantly different from zero. Indeed, according to the hostile account of leftist Deng Liqun, Hu Yaobang in 1984 required Central Organization Department approval for appointments of prefecture/divisional level cadres (Deng Reference Deng2005, 342). This effectively allowed Hu to select a pool of junior cadres for promotion into the Central Committee at the 13th Party Congress. Thus, even though Hu had been removed as the party secretary general by the 13th PC, Deng Xiaoping and the other elders apparently did not alter too drastically Hu's personnel arrangements. Broad Ties exerted a slightly stronger and more certain impact on promotions at the 13th PC than the other ties measures. This suggests that Hu deployed an expansive factional recruitment strategy that included not only co-workers, but also fellow Hunanese and colleagues and students at the Anti-Japan University. Given that he was the last member of the Long March generation to serve as PSG, the broad base of Hu's faction is not surprising. As we suspect, Zhao Ziyang did not exert any influence on ACC promotions at the 13th PC.

At the post-Tiananmen 14th Party Congress in 1992, deposed party secretary general Zhao Ziyang still exerted some influence on ACC to CC promotions, although this effect was not significant across our four ties measures. Although removed in 1989, Zhao had nearly two years between the 1987 13th Party Congress and June of 1989 to put promotion plans in place, and despite a wide-ranging purge of his followers after 1989, some in his factions still obtained promotions. The residual influence of deposed party secretary generals on ACC to CC promotions in subsequent party congresses suggests some degree of institutionalization in the cadre promotion process (Huang Reference Huang and Li2008; Li Reference Li, Naughton and Yang2004). As veteran organization department official Cui Wunnian recalls, the party in the 1980s spent a great deal of effort building up the reserve cadre system, which placed a selected handful of cadres on a fast track for promotions (Cui Reference Cui2003, 92). Thus, when a secretary general placed many followers on the reserve cadre list, it would have been difficult for his successor completely to undo the list within the span of a couple of years.

At the 1992 14th Party Congress, Jiang Zemin was still an unseasoned leader who, by all account, slavishly followed instructions from the party elders. Thus, it is not at all surprising that ties with him had no impact on promotions at that congress (Lam Reference Lam1995; Gilley Reference Gilley1998, 189; Fewsmith Reference Fewsmith2001, 46). Jiang apparently came into his own by the 15th Party Congress and promoted several of his followers into the Central Committee and even the Politburo, especially after Deng fell ill (Gilley Reference Gilley1998, 308). Thus, Figure 1 shows that at the 15th Party Congress, having Broad Ties and Restrictive Work Ties with Jiang significantly raised an ACC member's probability of being promoted into the CC. In the case of Restrictive Work Ties, the impact was quite large, at 40%.

At the 16th Party Congress, Jiang Zemin maintained the powerful Chairmanship of the Central Military Commission, but ceded the party secretary general position to Hu Jintao. Thus, Broad Ties and Restrictive Work Ties with Jiang Zemin still elevated the probability of a CC promotion, although the impact of ties with Jiang was no longer significantly different from zero. Rather than concluding that Jiang avoided the factional game at the 16th PC, we interpret this result as the product of Jiang focusing his factional activities at the lower end and the very high end of the ACC/CC spectrum. That is, Jiang systematically promoted his cronies into the ACC pool in the first place, and spent a lot of effort to promote a few key cronies into the Politburo Standing Committee (Shih et al. Reference Shih, Adolph and Mingxing2012; Li Reference Li, Naughton and Yang2004).

Our analysis shows that, in contrast to Jiang, Hu Jintao, the incoming secretary general, likely had a strong hand in promoting his followers from ACC membership to full CC membership at the 16th PC. Broad Ties with Hu Jintao, which records native and education ties in addition to work ties, does not show any impact on promotions at the 16th PC, suggesting that Hu did not pursue a broadly based factional recruitment strategy. However, all three measurements of work ties with Hu Jintao significantly increased the probability of CC promotions during the 16th PC. Restrictive Work Ties, which likely recorded ties with Hu Jintao with fewer Type 2 errors, shows that ACC members with Hu Jintao ties were nearly 60% more likely to get a promotion to full CC membership, a large impact.

Surprisingly, at the 17th Party Congress, neither Hu nor Jiang exerted any systematic influence on ACC promotions for most of our ties measurements. Although the Hu Jintao coefficients are generally in the right direction and show some systematic tendency for Complete Work Ties and Early Work Ties, the noise around all of these measurements remains significant. Restrictive Work Ties with Hu Jintao, however, once again shows a significant impact on ACC promotion at the 17th PC. This result strongly suggests that a restrictive definition of work ties reduces Type II errors in measuring factional ties. However, even Restrictive Work Ties shows that the Hu Jintao advantage has fallen from 60% at the 16th PC to around 30% at the 17th PC. We see the weaker and more uncertain Hu Jintao effect at the 17th Party Congress as more evidence of a cohort effect in ACC to CC promotions.

At the 18th Party Congress, Xi Jinping exerted a strong systematic impact on ACC members’ promotions into the CC, but not Hu Jintao. This is a surprising result given that the incumbent secretary general typically still took charge of the party congress of his retirement (Li Reference Li2007). Instead, all four of our Hu Jintao ties variables report statistically insignificant results, while Xi Jinping ties increased the probabilities of a promotion from ACC to CC by 20–30%. Similar to Hu Yaobang at the 13th PC and Jiang Zemin at the 15th PC, Broad Ties is significant at the 18th PC, suggesting that Xi deployed a wider factional recruitment pattern than his predecessor Hu Jintao.

Overall, it seems that greater institutionalization in the Chinese Communist Party has not diminished top leaders’ tendency to employ a broad approach in faction building. Three of the five reform era party secretary generals recruited not just work colleagues, but also fellow natives and alumni into their factional networks. Also, two of the three PSGs who used a broad-based approach came from the post-Long March generations, who were presumed to be more specialized than their predecessors. In the meantime, it is unclear that focusing on work ties accumulated by the patrons in the earlier stages of their careers provides any advantage in tracking their factions. Instead, Restrictive Work Ties seems to capture work ties accurately more often than do the other work ties measurements.

This set of logit regressions also reveals that although Hu Yaobang had been removed as the secretary general by the 1987 13th Party Congress and Zhao Ziyang had been removed by the 1992 14th PC, they exerted some influence on the promotions of ACC members to the CC in these two congresses respectively. First, the arrangements that they had made prior to their dismissals, especially in the case of Hu, continued to affect promotions in congresses after their removal (Deng Reference Deng2005, 442). Again, the reserve cadre system likely played an important role in maintaining the influence of deposed party secretary generals at least in the few years after their removal.

Second, the incoming secretary general seemed to have greater say over ACC to CC promotions than previously thought. Both Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping were able to systematically promote their followers from the ACC level to the CC level at the 16th and 18th PC respectively, despite being new party secretary generals at the time. In contrast, the outgoing secretary generals exerted much weaker influence. With the exception of party secretary generals who had been forced out of power before their terms ended, the party secretary general who had retired in the previous party congress exerted no systematic impact on ACC promotions. This is especially striking for the 16th Party Congress, which saw the Jiang Zemin to Hu Jintao transition. According to existing accounts, Jiang Zemin took strict control over personnel appointments at the congress and dominated the entire proceedings of the congress as the chairman of the presidium, which made all the procedural decisions for the congress (Zhang Reference Zhang2002a; Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2001; Li Reference Li2007). Yet, our results show that for ACC to CC promotions, ties with Hu Jintao exerted much greater systematic influence over promotions than ties with Jiang did.

These results are driven by a cohort effect inherent in how we measure factional variables. That is, since factional clients had been the patrons’ colleagues earlier in their careers, their age likely was a few years junior to that of the patron. When the patrons first stepped into the party secretary general position, their clients were young enough to enjoy a CC promotion. By the time the patrons departed from the top positions, even followers from a younger corhort likely had reached retirement age for an ACC member, given that a secretary general had among the highest retirement age in the regime. The more successful followers competed at the Politburo or Politburo Standing Committee levels, which had the higher retirement age of 70, or aimed for jobs in the National People's Congress.

As outside observers of the regime, one can interpret this cohort effect in one of two ways. First, perhaps factions tended to shrink in the Central Committee as the incumbents aged because clients in the factions at a lower level were compelled to retire by official rules in the party. This forced incumbents to allow their successors to have a say in promotions at a lower level, leaving them to focus on the promotion of a small handful of junior colleagues to the Politburo and the Standing Committee. This certainly fits the pattern for Jiang Zemin, who concentrated his effort on the promotion of Zeng Qinghong, Huang Ju, Wu Bangguo, and Jia Qinglin into the Standing Committee at the 16th PC (Zhang Reference Zhang2002b). In this case, outside observers’ ability to map factions is not diminished. This also suggests that the retirement age constitutes a credible mechanism for power sharing between the incumbent party leader and potential successors. Given that an incumbent's faction is aging, the retirement rule will automatically clear slots for potential successors’ followers, at least at the ACC level.

An alternative possibility is that, although clients whom patrons had acquired earlier in their careers retired during the patrons’ tenures, the patrons acquired new, much younger clients in more or less random fashion later on in their careers. Indeed, Mao and Jiang each sought to promote their personal secretaries, drivers, and even spouses into the upper echelon of the party (Wu Reference Wu2004; Ye Reference Ye2009). Deng Xiaoping also had a record of identifying promising young cadres during inspections and catapulting them to the highest level, including Wang Zhaoguo, Zhu Rongji, and his bridge partner Wang Ruilin (Sun Reference Sun2014, 153, 181). These individuals had no previous work, native, or education ties with Deng, but they owed him their allegiance. If that were the case, standard algorithms to track factions would miss a rising share of a faction as the patron aged. In this case, the only way to maintain a relatively firm grasp on a faction is to pay constant attention to discussions within China on the latest junior cronies to various leaders. Because these young members of factions were drawn from a vast pool of completely unknown officials in more or less random fashion, intense qualitative research is needed to keep track of these faction members. Also, in this case, although the incoming party secretary general clearly had a say in ACC to CC promotions, the out-going party secretary general also competed to promote unknown junior faction members to the CC. Outside observers just have a harder time tracking these promotions. This interpretation of the data does not necessarily predict a benign power-sharing outcome.

ROBUSTNESS CHECK

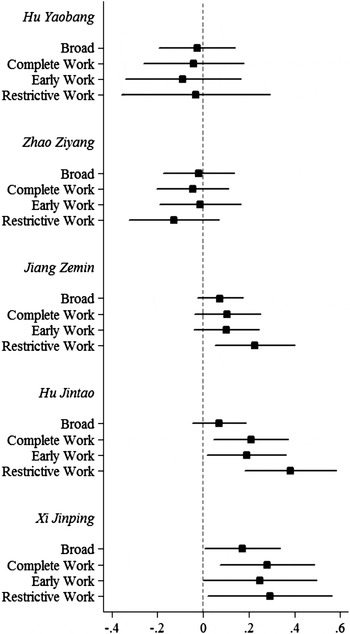

In order to show further that reform-era Chinese leaders pursued different logics of faction building, we pool all of our observations (ACC members) together into equations by party leaders (as opposed to by party congresses in Figure 1). For each leader, we estimate whether ACC members at congresses where a leader was the party secretary general or the immediately preceding party secretary general enjoyed a promotion advantage if they had ties with that leader. Figure 2 shows the marginal effect of having a tie with each party secretary on the predicted probability of being promoted from ACC to CC and above holding everything else at the means. These equations further include party congress dummy variables to net out any congress-specific shocks that might have distorted our previous results. Again, we include 90% confidence intervals in horizontal lines around the point estimates.

FIGURE 2 The Marginal Impact of Various Ties with the Former or Current Head of the Party on ACC Member Promotion into the CC: Pooled Estimates by Leader (Expected Values and 90% Confidence Intervals)

The results, shown in Figure 2, display a high degree of consistency with Figure 1. Unlike in Figure 1, any effect of ties with Hu Yaobang was washed out by the weak findings of the 12th Party Congress. However, for Jiang Zemin and Xi Jinping, Broad Ties still show a tendency to help advancement by factional clients. For Hu Jintao followers, Broad Ties still does not clearly help their advancement. Various work ties with Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Xi Jinping still show a strong tendency to enhance the chance of advancement by factional clients, with the strongest effect recorded for Restrictive Work Ties because of the higher accuracy of the variable. Similar to findings in Figure 1, Restrictive Work Ties with Hu Jintao increased an ACC member's chance of promotion by an average of 40%. For Xi Jinping, all three measurements for work ties raised one's promotion probability by around 30%.

CONCLUSIONS

The above analysis shows a very robust effect of factional ties with the party secretary general on an official's promotion prospects in the reform era. In all but the 12th and 14th Party Congress, ACC members with ties with either the incoming or the incumbent party secretary general gained a higher chance of obtaining full Central Committee membership, all else being equal. Furthermore, the analysis shows that leaders in the reform era continued to recruit faction members from fellow natives and school alumni, in addition to work colleagues. This finding casts a skeptical light on the argument that the professionalization of the cadre body has rendered factions even more based on shared work experience (Huang Reference Huang and Li2008). To be sure, given the focus on the factions of the party secretary general, it is quite possible that there is a selection effect at work. That is, officials with broad factions that transcended work colleagues had a higher chance of becoming the party secretary general. Still, future work should explore additional utility for the patron from having a broader faction.

We further find that among clients who were former work colleagues, there is little difference between work-based clients acquired prior to a patron joining the Politburo and work-based clients acquired throughout the patron's career. Again, given patterns of arrests in the Zhou Yongkang clique, this finding is somewhat surprising. Finally, we show that observers likely can obtain the most accurate identification of work-based faction members by tracking officials who were rotated either into or out of a patron's work unit while the patron and the client overlapped there.

From a methodological perspective, this analysis cautions us from relying too much on any particular factional measurement. When a party secretary general indeed pursued a broad strategy of factional recruitment, the broadest definition of a faction can perform just as well as the most restrictive definition of faction in predicting promotions. When one wants to gauge the impact of factional ties on the distribution of a key regime good, we recommend using qualitative insights on the style of a patron to guide the usage of factional measurements. Also, in robustness check, one should apply several definitions of factions to see what factional strategy the patron might have pursued. One cannot assume a priori that a given faction mainly would be based on one attribute.

This article uncovers two additional ways in which factional politics evolved around formal institutions, as predicted by Nathan (Reference Nathan1973), which deserve further inquiry. First, the system of cultivating a pool of reserve cadres likely allowed even purged party secretary generals to exert some influence on cadre promotions even after their removals. Second, the retirement rule likely meant that incoming secretary generals were able to have the greater influence on ACC to CC promotions during their first term, before their contemporaries retired, than during their second term, when many of their contemporaries had either retired or had been promoted to levels with higher retirement age. Such institutionalization, which constrained political behaviors to some degree, did not necessarily lead to “civility,” as Nathan predicted (Nathan Reference Nathan1973). Rather, some institutions, such as the reserve cadre system, had a weak impact on high-level struggles, while other institutions, such as the retirement rule, merely shaped or may have even exacerbated factional struggles. For example, the retirement rule meant that when one was purging one's enemy, even junior members of a faction would have to be purged, lest they exact their revenge after one's retirement. At the very least, every Politburo Standing Committee member fought to promote a trusted follower into the Politburo Standing Committee as insurance against political attacks, which made the selection of PSC members highly contentious (Zhang Reference Zhang2002b). In any event, the recent wholesale purge of the elite in China suggests something besides a harmonious power-sharing equilibrium.

Despite recent papers using factional variables to explain political outcomes, many questions remain unanswered for elite Chinese politics. First, this study and existing works have focused on the impact of factional ties on promotions, but what about the impact of factional ties on policies? The contribution to this volume of Efird, Lester, and Wise shows that political actors in difference positions can have an impact on policy outcomes; but perhaps we can get a more finely tuned prediction on policy outcomes if we conceive of these political actors as networked. Although factions are not policy oriented, factions may mobilize officials in the network to support a policy that benefits the patron, or may create rent seeking opportunities for members of the faction. Again, the Zhou Yongkang case is illustrative.

Second, it remains an open question whether the size, strength, and composition of one's faction increases the probability of a patron's political survival or bestows the patron some benefits. The existing literature has focused on the implications of factionalism on the clients but has assumed that the patrons reap some unobserved benefits from having a faction. Keller's work begins to answer this question by observing how actors in different positions in a multi-node network fared in terms of promotion. Future research needs to first identify regime goods, including survival, money, and promotions for family members, for the patron and examine whether having a stronger or larger faction will increase the allocation of those goods to the patron. Related to this, one can inquire whether having more faction members in the military or the police will increase the amount of goods allocated to the patron.

Finally, if different leaders indeed pursued different strategies in forming factions, the question is what “shape” faction may generate the greatest success in terms of factional survival and obtaining the highest position for the patron of a faction. For example, is pursuing followers on the basis of native place a winning strategy? What are the costs associated with having a faction that is too large? Future research on the Chinese elite can uncover these questions.