Introduction

Global issues such as climate change, food security and food safety are at the forefront of various policy and academic debates. As industrial agriculture continues to be scrutinized, there are calls for alternative farming systems to meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Eyhorn et al., Reference Eyhorn, Muller, Reganold, Frison, Herren, Luttikholt, Mueller, Sanders, Scialabba and Seufert2019). In today's environment, problems associated with conventional farming systems are tragically noticeable and have drastic effects on the environment and public health (Horrigan et al., Reference Horrigan, Lawrence and Walker2002; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2017). Organic agriculture has been popularized as an innovative approach to maintain the environment and human health as well as become a source of sustainable global food supply in the 21st century (Gomiero et al., Reference Gomiero, Pimentel and Paoletti2011; Reganold and Wachter, Reference Reganold and Wachter2016; Shennan et al., Reference Shennan, Krupnik, Baird, Cohen, Forbush, Lovell and Olimpi2017). Although recent years have witnessed an increase in organic farming, reaching a total area of about 72 million hectares and a market value of 97 billion euros as of 2018 (Willer et al., Reference Willer, Schlatter, Trávníček, Kemper and Lernoud2020), organic agriculture still occupies only 1.5% of the global agricultural land.

Organic agriculture has gained an excellent reputation from the ecological and food safety perspective, especially from the educated, middle-to-high income and health-conscious segments of the society (Rana and Paul, Reference Rana and Paul2017). Socially, organic farming has added benefits in terms of a better work environment, improved employment opportunities, education, health and livelihoods in less favored areas (Qiao et al., Reference Qiao, Halberg, Vaheesan and Scott2016; Jouzi et al., Reference Jouzi, Azadi, Taheri, Zarafshani, Gebrehiwot, Van Passel and Lebailly2017). However, the relative economic performance of organic vis-à-vis conventional farming remains contentious (Crowder and Reganold, Reference Crowder and Reganold2015; Reganold and Wachter, Reference Reganold and Wachter2016). Questions continue to be raised about the appropriateness of organic farming to feed the growing world population, which is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 (Connor and Mínguez, Reference Connor and Mínguez2012; Connor, Reference Connor2013). This question is even more relevant for developing countries where population is rising and poverty is rampant (Vanlauwe et al., Reference Vanlauwe, Coyne, Gockowski, Hauser, Huising, Masso, Nziguheba, Schut and Van Asten2014). The main criticism against organic farming lies in its relatively lower yields (and thus the need for more land to fill potential food supply gaps) and higher prices for consumers (de Ponti et al., Reference de Ponti, Rijk and van Ittersum2012; Seufert et al., Reference Seufert, Ramankutty and Foley2012; Ponisio et al., Reference Ponisio, M'Gonigle, Mace, Palomino, De Valpine and Kremen2015).

Nonetheless, empirical findings are rather promising and provide evidence of relatively lower yield gaps between organic and conventional farming systems (Badgley et al., Reference Badgley, Moghtader, Quintero, Zakem, Chappell, Aviles-Vazquez, Samulon and Perfecto2007; Schrama et al., Reference Schrama, de Haan, Kroonen, Verstegen and Van der Putten2018). For example, using large meta-datasets, de Ponti et al. (Reference de Ponti, Rijk and van Ittersum2012), Ponisio et al. (Reference Ponisio, M'Gonigle, Mace, Palomino, De Valpine and Kremen2015) and Seufert et al. (Reference Seufert, Ramankutty and Foley2012) reported yield gaps ranging from 19 to 25% between organic and conventional farming systems. Furthermore, the relative performance of organic and conventional farming is context-specific and can vary across crops and geographies (Seufert et al., Reference Seufert, Ramankutty and Foley2012; Seufert and Ramankutty, Reference Seufert and Ramankutty2017). For example, in water scare environments, organic farming tends to provide higher yields than conventional farming because of the higher water-holding capacity of soils in the former (Gomiero et al., Reference Gomiero, Pimentel and Paoletti2011). Also, a review article (based on 88 papers) revealed higher yields (26%), gross margins (51%) and organic carbon content (53%) under organic farming in the context of the tropics and subtropics (Te Pas and Rees, Reference Te Pas and Rees2014). More importantly, growers have become more profitable under organic agriculture (Crowder and Reganold, Reference Crowder and Reganold2015; Berg et al., Reference Berg, Maneas and Salguero Engström2018) as the popularity of organic produce rises among urban consumers (Rana and Paul, Reference Rana and Paul2017).

In general, the future of global food supply depends on the wider adoption of sustainable food systems that include organic agriculture, reductions of food waste and changes in dietary habits, especially against the most resource-intensive animal-based protein sources (Tscharntke et al., Reference Tscharntke, Clough, Wanger, Jackson, Motzke, Perfecto, Vandermeer and Whitbread2012; Garnett et al., Reference Garnett, Appleby, Balmford, Bateman, Benton, Bloomer, Burlingame, Dawkins, Dolan and Fraser2013; Muller et al., Reference Muller, Schader, Scialabba, Brüggemann, Isensee, Erb, Smith, Klocke, Leiber and Stolze2017). In the Global North, organic produce generally fetches higher prices than conventionally farmed products. Unfortunately, available data are generated from high-income countries (Kniss et al., Reference Kniss, Savage and Jabbour2016) and thus more evidence is needed to guide policies supporting sustainable development in developing countries. It remains the subject of empirical work to determine whether the transition to organic agriculture can generate net economic benefits across products and geographies. Smallholder farmers in many developing countries continue to suffer from low yields, market uncertainty, high transition costs and poor farm management skills (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Dismukes, Chambers, Greene and Kremen2007; Qiao et al., Reference Qiao, Halberg, Vaheesan and Scott2016; Jouzi et al., Reference Jouzi, Azadi, Taheri, Zarafshani, Gebrehiwot, Van Passel and Lebailly2017). Furthermore, the development and professionalization of the organic sector, accompanied by increased international trade, has called for third-party certification to become the norm in most developed organic markets; anyone wishing to sell their produce on high-value markets must meet such established criteria (Darnhofer, Reference Darnhofer2006). However, third-party audit certification might not always be appropriate in developing countries and may be too expensive to implement (Faour, Reference Faour2015; Salame et al., Reference Salame, Pugliese and Naspetti2016; Skaf et al., Reference Skaf, Buonocore, Dumontet, Capone and Franzese2019; Mardigian et al., Reference Mardigian, Chalak, Fares, Parpia, El Asmar and Habib2021).

This study aims to identify the factors affecting the expansion of organic agriculture and analyze the economic performance of organic tomato in Lebanon. Organic farming, although started in the nineties in Lebanon, remains a tiny niche (Chbeir and Mikhael, Reference Chbeir and Mikhael2019); an innovative approach is needed to promote the sector and attract the educated, younger generation in agriculture. Given the slow growth of organic farming in Lebanon, the empirical study aims to answer several questions: (1) Do production costs justify the high market price? (2) What other factors, if any, make organic production in Lebanon highly expensive? (3) Where to intervene in the value chain to enhance the profitability of organic farming for the producers and affordability of organic produce to consumers? and (4) Are there innovative solutions that were tested in Lebanon or other developing countries that could be beneficial to smallholders? By answering these questions, the study seeks to contribute to the organic farming literature as follows. First, the economic performance of organic agriculture is context-specific. Such studies are scant in Lebanon that is characterized by net food imports and unstable political and market environment. Secondly, agricultural land is relatively scarce in Lebanon; thus, more evidence is needed to identify important challenges when farmers make farm decisions, including the decision to transition from conventional to organic farming practices. Thirdly, there are unique institutional (e.g., certification procedures) and marketing challenges across boundaries and crop groups.

The paper develops as follows. First, we provide a review of relevant studies in developing countries. Secondly, we aim to zoom in on the economical sustainability of organic agriculture in the Middle Eastern context and present a case study that analyzes the profitability of organic tomato in Lebanon. Finally, the main findings and potential suggestions are discussed.

Literature review: economic performance of organic farming in developing countries

Undoubtedly, organic farming provides many ecological and social benefits (Gattinger et al., Reference Gattinger, Muller, Haeni, Skinner, Fliessbach, Buchmann, Mäder, Stolze, Smith and Scialabba2012; Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, Halberg and Bhatta2012); however, the economic aspect remains a first-order condition for the wider adoption of organic farming practices. Many argue that organic farming is still less efficient to sustain food production in developing countries (Bourn and Prescott, Reference Bourn and Prescott2002; Connor and Mínguez, Reference Connor and Mínguez2012; Smith-Spangler et al., Reference Smith-Spangler, Brandeau, Hunter, Bavinger, Pearson, Eschbach, Sundaram, Liu, Schirmer and Stave2012). A review of the relevant literature that applied poverty, household income (net profit), external input costs and/or prices shows that organic farming can be profitable in developing countries, although yield gaps can be as high as 30–40% (Seufert et al., Reference Seufert, Ramankutty and Foley2012; Ponisio et al., Reference Ponisio, M'Gonigle, Mace, Palomino, De Valpine and Kremen2015). Apparently, many of the economic benefits of organic farming come from the price premium. For example, Adamtey et al. (Reference Adamtey, Musyoka, Zundel, Cobo, Karanja, Fiaboe, Muriuki, Mucheru-Muna, Vanlauwe, Berset, Messmer, Gattinger, Bhullar, Cadisch, Fliessbach, Mäder, Niggli and Foster2016) and Bett and Ayieko (Reference Bett and Ayieko2017) in Kenya, and Yadava and Komaraiah (Reference Yadava and Komaraiah2020), Eyhorn et al. (Reference Eyhorn, Van den Berg, Decock, Maat and Srivastava2018) and Mariappan and Zhou (Reference Mariappan and Zhou2019) in India, documented the profitability of organic farming on rice, wheat and maize. In Indonesia, Adiprasetyo et al. (Reference Adiprasetyo, Sukisno, Ginting and Handajaningsih2015), Fachrista et al. (Reference Fachrista, Irham and Suryantini2019) and Widhiningsih (Reference Widhiningsih2020) reported similar evidence about organic vegetables. In fruits, Kleemann (Reference Kleemann2011) and Kleemann et al. (Reference Kleemann, Abdulai and Buss2014) confirmed the economic benefits of organic certification for pineapple farmers in Ghana. Organic farming is also reported to have improved the income of cotton growers in India (Fayet and Vermeulen, Reference Fayet and Vermeulen2014; Altenbuchner et al., Reference Altenbuchner, Vogel and Larcher2017) and honey producers in Ethiopia (Girma and Gardebroek, Reference Girma and Gardebroek2015).

Despite such promises, however, small farmers are reluctant to transition to organic agriculture. Also, the dichotomy between conventional and organic practices and stringent certification requirements may favor industrialized organic farming (and exclude small farms); some farms could fulfill requirements without having certification (Darnhofer et al., Reference Darnhofer, Lindenthal, Bartel-Kratochvil and Zollitsch2010; Konstantinidis, Reference Konstantinidis2012). Consequently, blended approaches such as agro-tourism (e.g., Davis et al., Reference Davis, Hill, Chase, Johanns and Liebman2012; Reganold and Wachter, Reference Reganold and Wachter2016) and local participatory systems for certification such as ‘Participatory Guarantee Systems’ (PGS) (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Tovar, Gueguen, Humphries, Landman and Rindermann2016; Home et al., Reference Home, Bouagnimbeck, Ugas, Arbenz and Stolze2017) may be preferred to promote the wider acceptability of organic practices in developing countries.

The integration of organic farming practices with ecosystem services has shown some promising results by increasing the economic value of organic farms (Porter et al., Reference Porter, Costanza, Sandhu, Sigsgaard and Wratten2009; Sandhu et al., Reference Sandhu, Wratten and Cullen2010). A unique advantage of such a blended approach is that it can add more value to the product by bringing producers and consumers in one place and expanding the contribution of organic agriculture beyond goods production (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Chen and Huang2006; Vrsaljko et al., Reference Vrsaljko, Turalija, Grgić and Zrakić2017). Several studies have documented the benefits of the agro-touristic model in the context of developing countries (e.g., Aoki, Reference Aoki2014; Arida et al., Reference Arida, Wiguna, Narka and Febrianti2017; Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Kline, Swanson, Best and McKinnon2017; Fantini et al., Reference Fantini, Rover, Chiodo and Assing2018). For instance, in countries such as Indonesia, Cuba, Brazil and Nepal, this approach has shown promising outcomes by increasing household incomes and creating more jobs (Arida et al., Reference Arida, Wiguna, Narka and Febrianti2017), food security (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Kline, Swanson, Best and McKinnon2017), creating marketing relationships (Fantini et al., Reference Fantini, Rover, Chiodo and Assing2018) and improving human health (Aoki, Reference Aoki2014). Similarly, PGS, as an alternative certification system, may offer support for small organic farms by creating access to local and regional markets, as demonstrated in several countries such as Mexico and Brazil (Sacchi et al., Reference Sacchi, Caputo and Nayga2015; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Tovar, Gueguen, Humphries, Landman and Rindermann2016, Reference Nelson, Tovar, Rindermann and Cruz2010; Kaufmann and Vogl, Reference Kaufmann and Vogl2018).

In summary, empirical studies in several developing countries revealed that organic farming can be an important alternative to intensive agriculture. The evidence suggests that organic farming is economically sustainable but varies across geographies and crops, suggesting the need for further studies in various contexts. Furthermore, available studies suggest the need for alternative approaches and certification procedures to enhance the attractiveness of organic farming for smallholders in developing countries.

Methods

Data collection

First, a focus group was held with the national technical organic committee at the Lebanese Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) to provide and discuss an overview of the sector, its public policy, its trends and challenges.

Secondly, data about organic farmers in Lebanon, including their contact names, crops grown, farm location and size, were obtained from the MoA. Based on this information, it was possible to choose tomato production at the food system of this study. Tomato is one of the major horticultural crops in Lebanon and has the highest number of organic growers per crop. We obtained a list of 30 certified organic tomato farmers that operating at the time of the study.

Finally, a structured questionnaire, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the American University of Beirut, was used to collect relevant data related to production costs, revenues and profits. All the 30 organic tomato farmers were contacted for an interview. However, only 15 of the farmers were able to participate in the study. Data regarding the production costs included fixed costs, establishment costs and variable costs such as labor and other inputs. Current and recollection data over the last 2 years were sought to gather yield, production, marketing information from the farmers. A farm visit accompanied the collection of data from the farmers.

Complementary data

To complement information from farmers and to determine selling prices and market channels, a market study was also carried out among organic shops and farmer markets in Beirut, the capital. These markets represent different marketing chains of organic tomato in Lebanon. The market study included, among others, the business relationship between organic farmers and organic shops, how organic shops identify farmers with organic certification, the seasonality of demand for organic produce, the order quantity, characteristics of the buyers (final consumers), selling prices and their assessment about the future of organic farming in Lebanon.

For conventional farming, a secondary data source was used. Accordingly, data for detailed costs of conventional tomato farming were acquired from a reference tool entitled ‘Production Costs of all Agricultural Products in Lebanon’, which was published in Arabic in 2016 by the Association of Importers and Distributors of Supplies for Agricultural Products in Lebanon.

Results

Overview of the Lebanese organic agriculture

Over the past few decades, the contribution of Lebanese agriculture to household income and food security dropped significantly due to the lack of effective policy, changes in temperature and rainfall patterns, water scarcity and increasing population. Urbanization has also been a major factor in the decline of the agriculture sector in Lebanon. In fact, Lebanon was once considered an agricultural country as late as the start of the Lebanese civil war (Salame et al., Reference Salame, Pugliese and Naspetti2016). However, following the end of the war, there have been major construction activities, especially along with the coastal areas (Faour, Reference Faour2015). This has significantly reduced the agricultural land and, potentially, contributed to the increased use of high-input practices (Skaf et al., Reference Skaf, Buonocore, Dumontet, Capone and Franzese2019; Mardigian et al., Reference Mardigian, Chalak, Fares, Parpia, El Asmar and Habib2021). Currently, the production agriculture sector contributes about 5% of GDP, employs 8% of the effective labor force and involves 20–25% of the active population, either on a part-time or full-time basis (Marzin et al., Reference Marzin, Bonnet, Bessaoud and Ton-Nu2017).

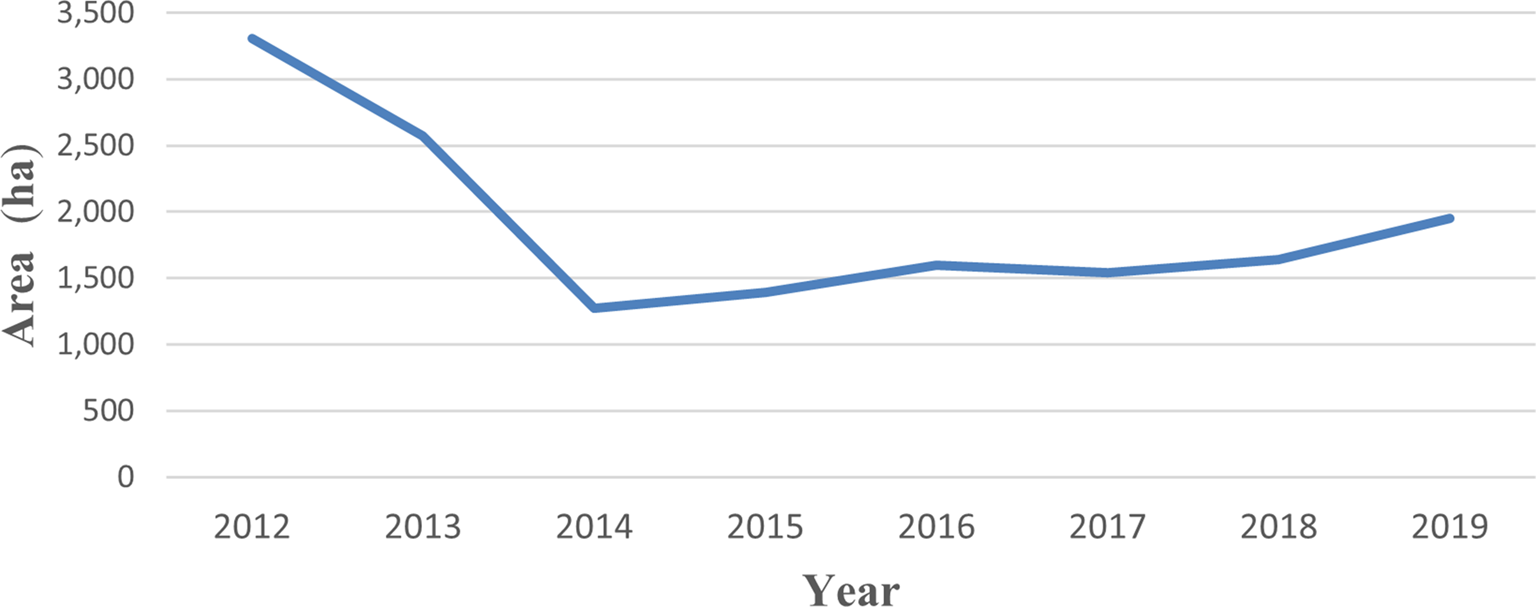

Cognizant of the multifaceted contribution of agriculture to the national economy, the Lebanese government is trying to revitalize the sector and increase its contribution to the GDP from 5 to 8%. In light of the ongoing and unprecedented triple crises in Lebanon – economic, financial and the corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic—the government has published a strategic document, the ‘Lebanon National Agriculture Strategy 2020–2025’ (MOA, 2020). The strategy stipulates the agri-food sector as a national priority and a key driver for transforming the Lebanese economy. More importantly, the document highlights the urgency of creating strong linkages between ‘sustainable agriculture and preservation of ecosystem services and/or eco-tourism’ to take advantage of the ‘highly valued cultural and culinary heritage, and the increasing awareness for healthy and organic food’ in Lebanon (MOA, 2020: 33). The strategic document targets a 30% increase by 2025 in the number of certified organic operators in Lebanon compared to that of 2019. As of 2019, the total area with certified production was 1952 ha, mainly in plant production. As shown in Figure 1, the area under organic agriculture was 3303 ha in 2013 but significantly dropped to 1276 ha in 2014 and has shown a steady growth thereafter.Footnote 1 Currently, there is only one certification body granting certifications for organic farmers. Lebanon also lacks organic producers' associations and organic market associations, which are critical to provide the necessary skills, scale and resources and create better market opportunities for organic fruits and vegetables, which account for the majority of the current organic market in Lebanon.

Fig. 1. Organic agriculture area (ha) in Lebanon (2012–2019) (source: MOA, 2020).

Drivers and transition to organic

An estimation of the market share of organic foods in the overall Lebanese market is less than 1% (Rahhal, Reference Rahhal2016). This is mainly attributed to supply-side constraints as the demand for organic produce is on the rise. Lebanon being a high-middle income country, the demand for organic products is highly driven by the health issues, the environmental complications of the alternatives and the increasing awareness tied to organic foods. Yet, organic products when available on the market are exceedingly expensive beyond the reach of low- to middle-income households; producers are unable or unwilling to lower prices. When interviewed, organic producers and sellers seem to attribute high production costs to justify the high prices of organic products in Lebanon. However, there is almost no empirical data showing the relationships between organic production costs and extreme market prices. Some leading organic growers in Lebanon also seem to attribute the high organic prices to lower yields and lack of multi-crop farms (Rahhal, Reference Rahhal2016).

We conducted this case study with the objectives of determining the production costs, mapping the organic value chain, determining the profitability of organic farming for farmers and comparing it with the conventional one of selected crops in the same value chain. The certified organic farmers that participated in this study had a medium-size organic farm ranging from 1.2 to 4 ha. They were certified by Controllo e Certificazione Prodotti Biologici (CCPB), an Italian-based agency, that certifies organic and eco-friendly products around the world and the only active certification body in Lebanon through its affiliate CCPB Middle East at the time of the field study. Most of the farms needed 2–3 years as a transition period before they were granted the certification. Most of the farms were certified after 2010 except for two farms. This may suggest the rising trend in the last decade. The certification average cost was 600–650 USD per year.

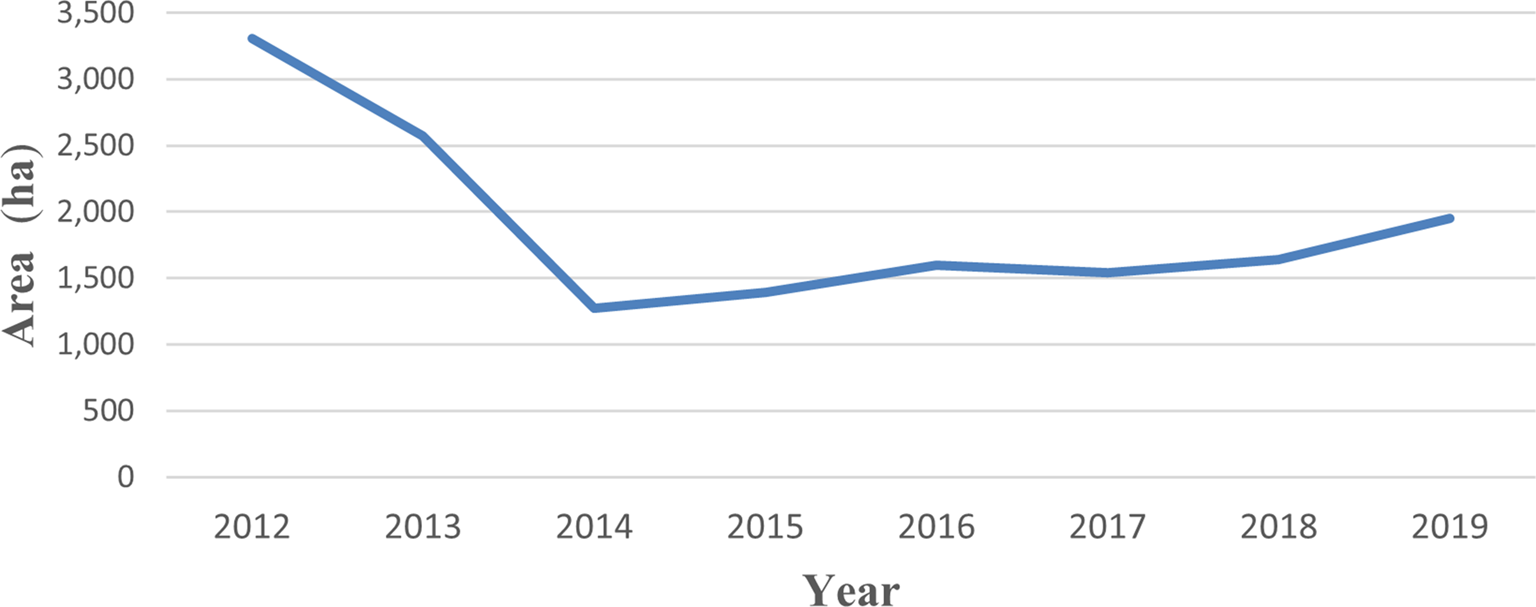

Organic tomato producers were asked about the factors motivating the transition to organic farming. The increasing demand toward healthier diets was a main drive for the interviewed farmers to transition to organic. Since these farmers were producing for the market, this motivation will likely be due to the increasing demand for organic products in the Lebanese market out of health concerns that consumers have in general. Figure 2 shows the main factors stated by the farmers to transition to organic farming. However, only 47% of the farmers made a living in organic farming, while 53% mentioned that they depended on other sources for a living. This may raise a question about the economic sustainability of organic farming as the main source of living for all farmers in Lebanon.

Fig. 2. Factors motivating the transition to organic farming in Lebanon (multiple answers possible).

Production costs

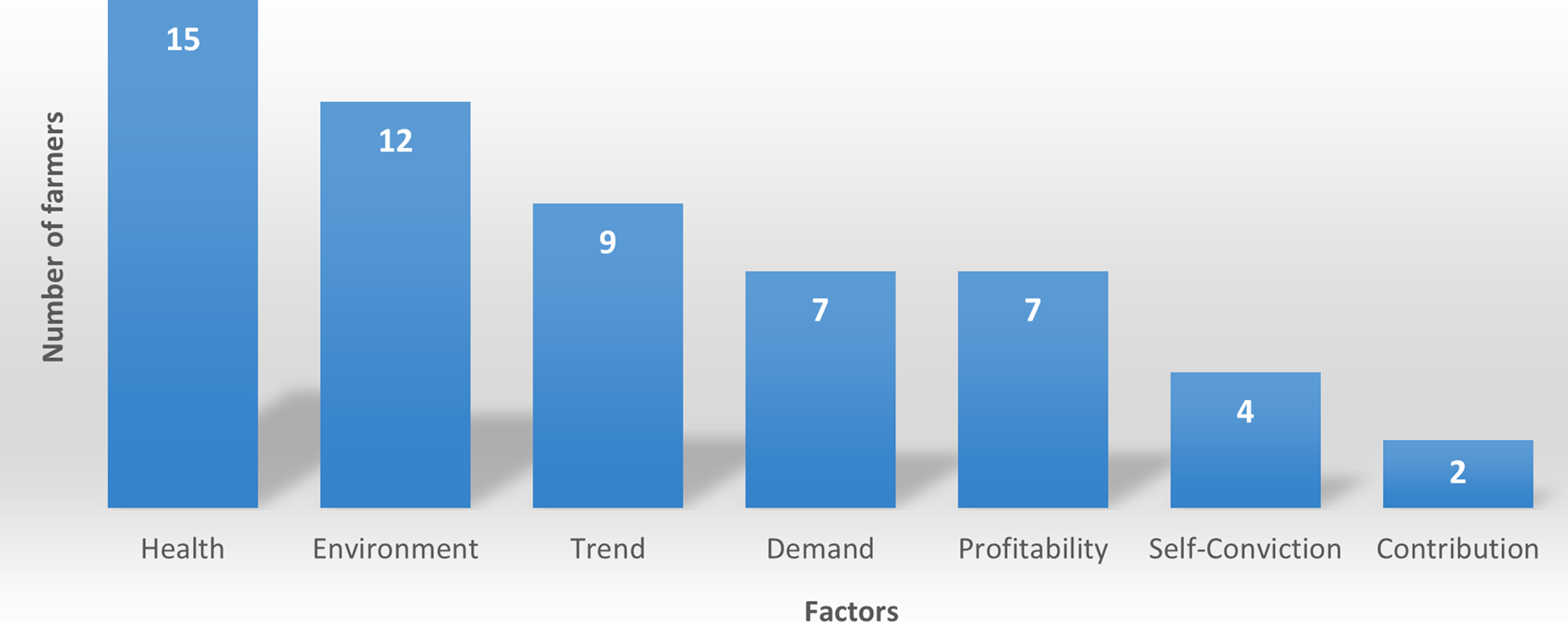

All costs incurred in the growing organic tomato were gathered during the field study. Table 1 lists the production costs for 1000 m2 or 0.1 ha (the standard unit for agricultural land in Lebanon) of tomato production under organic and conventional management in Lebanon. The direct comparison between production costs under the two systems showed an 11.60% increase in production costs of tomato under organic production to the conventional one.

Table 1. Comparison between organic and conventional production costs of tomato production per 1000 m2 a

a Organic production costs were generated from a questionnaire developed for the purposes of this study and conducted with 15 producers of certified organic vegetables in Lebanon. Conventional production costs were attained from the data published in ‘Production Costs of all Agricultural Products in Lebanon’.

b Include composting.

c Prorated costs of greenhouse structure and covers.

d An average cost calculated for the total surveyed farms area. A farmer having only 1000 m2 will pay $650 per yr for certification.

Labor and greenhouse costs are the major cost drivers under both farming systems. Although conventional farmers invest more in the use of pesticides for tomato production which particularly includes the use of herbicides for weed control, organic farmers invest more in labor costs due to manual weeding. Apparently, organic certification adds to the costs reported under organic tomato. As shown in Table 1, the prorated cost of certification was $25 per 1000 m2. However, the cost of certification is paid in a lump sum ($650 at the time of the study). Meaning, if farmers were to practice organic farming in a large area, the certification cost can be less expensive. Since most of the organic producers are smallholders, this certification cost remains a big chunk of the production costs. Currently, certification costs are paid in foreign currency (i.e., USD) as the certification body is a foreign company. This has a negative impact as the value of the cost increased exponentially with the devaluation of the local currency; since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the local currency has lost more than 80% of its value against the USD.

Yield and marketing channels

In a 1000 m2 or 0.1 ha plot of land, about 2750–3000 tomato plants can be grown. Based on evidence from our primary data, on average, the yield obtained from a standard organic tomato field, in this area, was 6 tons. The average yield from a standard tomato field under conventional was reported at 16 tons, according to the information from the Association of Importers and Distributors of Supplies for Agricultural Products in Lebanon.

In terms of outlets, more than 50% of the tomato farmers reported having sold 70% of their yield via organic produce distributor and no direct market access. This distributor has a well-established market coverage and dominates the organic sector in Lebanon. The rest of the farmers either sold their produce at the farm gate or the farmers market, the only available outlet for organic produce in the capital. Tomato farmers also experienced post-harvest losses, estimated to be 25% of retail value (15% due to pests and 10% due to returned produce). The profitability of organic tomato was highly dependent on the marketing channel.

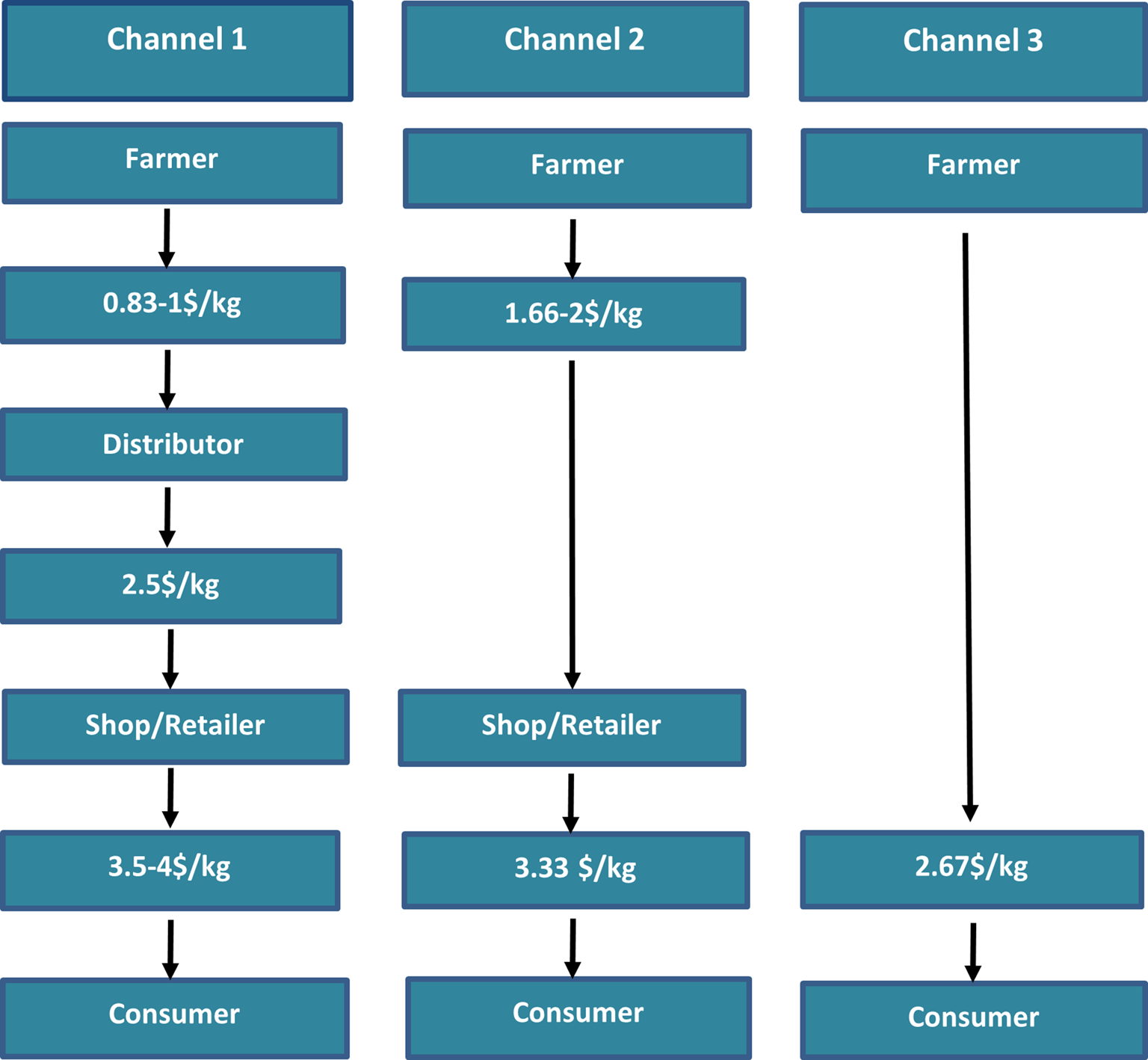

Based on the analysis of the tomato organic value chain, we have identified and mapped three marketing channels for organic tomato (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Marketing channels used by organic tomato growers in Lebanon. Source: own survey.

Channel 1: This channel has the longest chain. The farmer sells to a distributor at a price ranging from $0.89 to $1/kg. The distributor, in turn, sells the produce at $2.5/kg to organic shops or retailers, at a gross margin of 150–212.5%. Finally, organic shops or retailers sell organic tomato at a price of $3.5–4$/kg, or at a 40–60% margin. The gap between the farm gate price and the price that final consumers pay is extremely wide. Apparently, the main profit goes to the distributor in the study context. Of course, one may argue that due to the high perishability of tomatoes, distributors relatively bear higher risks as well as the overuse of (fancy) packaging materials. However, in the study context, such risks are minimal, as the demand for organic tomato is still very high and the distance between tomato farms to the final market is relatively short. Indeed, 10 out of 15 organic tomato farmers followed this channel, while eight of them followed both channels 1 and 3. Most of the farmers who followed this channel were big-size farms and would have to deal with intermediaries or have some kind of pre-arranged contractual agreement with organic distributors.

Channel 2: In this channel, the farmer skips distributors and directly sells to organic shops at a price ranging from $1.66 to $2/kg. The organic shops, subsequently, sell to the final consumers at $3.33/kg. As expected, the benefit to the farmers is much better than channel 1. In fact, all channel 2 members, including the final consumers, have added benefits compared to channel 1. We found three farmers who followed this channel.

Channel 3: This is a direct marketing approach and cuts out all the intermediaries. As shown in Figure 3, the farmer sells organic tomato at $2.67/kg to the final consumer either at the farmers market or farm gate. Indeed, this scenario appears to be the best for both the farmers and final consumers. Nonetheless, it has its risks for the tomato farmers. The farmer may not be able to sell his/her entire produce since the farmers market is not always available, and is located in the city, away from most of the rural farms. At the same time, accessibility to the farm may be difficult for consumers. Three farmers reported to having followed this channel.

Farmer's profitability

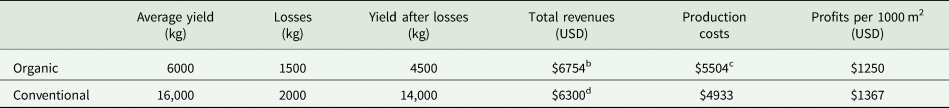

Using data collected on production costs, yield, losses, and selling prices, the profitability of organic tomato was calculated. The most representative channel based on the results described above was a mixture between channels 1 and 3 (70% to the distributor, and 30% directly to consumers). For this reason, the profitability of a typical organic tomato producer was calculated based on this formula (70–30). A comparison of profitability between organic and conventional management for tomato production is given in Table 2.

Table 2. Profitability of tomato production under organic and conventional farming in Lebanona

Note: All Production costs are in USD.

a Data for the organic production costs were generated through own surveys and for the conventional production costs were attained from published data ‘Production Costs of all Agricultural Products in Lebanon’.

b 70% of yield for distribution company with $1/kg as selling price: 3150 kg × $1 = $3150; 30% of yield for direct sale to consumers with $2.67 as selling price: 1350 kg × $2.67 = $3604.

c See Table 1 for the total cost calculations.

d Average price/kg for a conventional wholesaler is $0.45.

As can be seen in Table 2, organic tomato appeared to be less profitable in the study context, which was about $117 (per 1000 m2) less than that of the conventional one. The higher yield in conventional farming offsets the higher prices for organic tomato. Nonetheless, organic tomato can be more profitable if farmers cut out intermediaries and sell their produce directly to the consumers (channel 3).

Alternative approaches to promote organic farming: the agro-tourism model

In Lebanon, people have become more and more interested in authentic farm-based experiences and rural landscapes, which generate incomes for the rural communities (Ghadban et al., Reference Ghadban, Shames, Abou Arrage and Abou Fayyad2017). Recently, a few organic operators have adopted the model from ‘farm to fork’ and established an end-market on their farms to provide touristic activities such as restaurants with specialty chefs, kids park, kids' activities, culinary activities and special occasions (Fig. 4). This has attracted many people to spend their holidays, weekends and summer vacation in those agro-touristic areas (Ghadban et al., Reference Ghadban, Shames, Abou Arrage and Abou Fayyad2017). This has enabled the Lebanese people to connect to the farm and organic producers to increase awareness and value of organic products. Furthermore, these agro-touristic operators use social media to advertise their on-farm culinary and touristic activities and e-commerce platforms for direct sales. One of the co-authors was able to visit those agro-touristic farms and observe the farm culinary and touristic activities and the sale of organic products (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Coupling agriculture to touristic activities on organic farms in Lebanon. On-farm restaurant; chef serving fresh fruits from the farm; on-farm eggs haunting and on-farm kids activity. (Note: pictures are courtesy of Biomass and Bioland farms.)

Discussion

Based on analysis of the profitability of tomato under organic vs conventional practices in Lebanon, this section discusses the lessons learned from the case study and alternative approaches that could enhance the economic, ecological and social sustainability of organic farming in Lebanon and beyond.

Lesson learned from Lebanon's case

Analysis of organic tomato in Lebanon shows that production costs do not justify the high prices that final consumers pay, especially in the most-used channel (channel 1). In this channel, there is a huge margin between what the farmers receive and what the final consumer pays. On the other hand, organic farming can be profitable if there is a short path connecting farmers and final consumers (channel 3). In the case of tomato, organic yields are low, approximately a third of the yield under conventional farming. Due to the wider yield gaps, the profitability of organic farming largely depends on the channel choice. The issue for organic farmers in Lebanon is that they are not the ones benefitting from the high prices; the ‘middlemen’ (distributors) seem to have higher control over the organic sector in Lebanon. Surprisingly, many of the organic tomato growers (10 out of 15) ended up selling via the unprofitable, longer chain. This observable fact is somewhat strange to organic approaches elsewhere that favor short circuits (i.e., farmer markets and community-supported agriculture). Apart from production costs, different factors play a role in these high prices, some of which are better perceptions toward organic produce, but most of all the productivity issue, as organic tomato yield being less by 60% than the conventional and the higher risk that the producer encounter in organic farming due to the lack of effective inputs. Unfortunately, the distributor (‘middleman’) controls the prices in the organic shops and retailers and makes most of the profits. To a lesser extent, some overhead costs and losses due to its perishability play a role in the pricing strategy. The other factor may relate to the profession. If producers have another profession, which seems to be the case in Lebanon, they do not put enough time and effort to develop their market linkages. Also, the distributor is better equipped, having invested in warehouses, packaging facilities and the ability to apply international standards for export, and tends to have a contract farming arrangement with smallholders. Therefore, those farmers cannot individually supply to the desired market.

The way forward to enhance organic farming in Lebanon and beyond

Organic agriculture is a national and a global need, and Lebanon must work on improving the weaknesses, and take advantage of the opportunity at hand. Given Lebanese touristic and rich natural heritages along the Mediterranean Sea and the family based agrarian structure, there is a tendency in the country to move toward an agro-touristic model in organic farming. In such a blended model, the producer establishes an end-market on the farm coupled with touristic activities (i.e., restaurants with specialty chefs, kids park, kids' activities, culinary activities, special occasions, etc.). This way of adding value to the farm and its organic products enables the producers to diversify their revenue (touristic and agribusiness) and fetch a high price for their organic products. Increasing consumers' awareness of the public health issues related to the conventional approach is likely to raise the demand for fresh and local produces, especially organic vegetables and fruits. Similarly, the need to overcome high production costs, including third-party certifications, is likely to nurture the agro-tourism model where an owned plot of land, usually a bit farther away from people clusters and in an enchanted place, is turned into an organic agro-touristic farm. Optimally, the land must have never been cultivated or used for conventional farming before, as this will limit contamination problems, pest pressure and costs of transition to organic. Ideally, the land would have a natural undisrupted well of water or spring flowing to help irrigate it, which ensures the water for irrigation is clean. Some organic producers or distributors have already established their restaurants and recipes and on-farm concepts of serving daily produces. By doing so, they educate the consumer and engage them in the organic experience and ultimately nurture the country's agro-tourism, which emphasizes health improvement and sustainability of living along with farm biodiversity. Although the current financial and economic crisis in Lebanon and the COVID-19 pandemic may have a negative impact on the agro-tourism model, the crises have given important lessons about the role of local (short) food supply chains, including the organic food chain. Such behavioral changes among consumers tend to benefit the agro-tourism model in the medium to long term.

Another important question worth answering is where to intervene in the organic value chain to make organic products more accessible and consequently organic farming in Lebanon more competitive. We suggest several steps that need to be applied to meet the consumer's high demand for organic products, but at the same time enhance the affordability of organic produce to the low- and middle- class. Considering the low productivity made by organic farmers, the latter needs technical assistance and training to increase their efficiency in organic farming. Also, organic farmers must be oriented toward a solid marketing strategy, where no company or shop can control their sales and prices (Rana and Paul, Reference Rana and Paul2017). Primary producers should improve their communication with downstream actors and final consumers by the means of new tools such as social media or mobile apps. This can benefit both the farmers and the final consumers. For consumers, direct contact with the farm will increase trust, and prices will become more reasonable due to the direct chain between them and the farmer. At the same time, even if prices are somehow lower, farmers' profits will increase by avoiding intermediaries.

Also, organic farmers can assemble themselves in the form of producer groups or cooperatives that are based on mutual trust and long-term partnerships to increase their bargaining power and create better market opportunities. Here, the PGS that proved effective in some developing countries (such as Brazil, India and Mexico) can be a trustful way. If well introduced, PGS can allow producers to have a reliable collective certification method without necessarily depending on one third-party certification body as is the case currently in Lebanon. This can also be expected to have a positive impact on lowering certification costs, which were found to be a factor in the higher production costs for organic in this study. In fact, PGS is an organic quality assurance mechanism recognized by IFOAM (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements) as an alternative to audit certification. Under this system, farmers, producers and extractivist, organized in groups, collectively carry out conformity assessment activities and share responsibility for the certification decision, where possible supported by technicians and consumers.

Finally, more organic markets should be made available, especially in rural areas. The farmers market ‘Souk el Tayyeb’ in the capital Beirut is a great initiative that helps farmers sell their organic produce, but the Lebanese organic market and sector need more markets in different regions in a way that helps more farmers to have access to such markets. Also, the Ministry of Agriculture, as mentioned in Urfi et al. (Reference Urfi, Hoffmann and Kormosné Koch2011), should provide some kind of financial support or subsidized agri-loans to compensate farmers for the revenues lost during the transition period and extension services to improve their management skills necessary for organic farming. In this way, organic farmers are encouraged to continue farming organically, and more farmers are motivated to transition to organic.

Conclusions

The future of food value chains has increasingly been reliant on the wider adoption of sustainable farming practices that include organic agriculture. However, the standard model when transferred to developing countries faces difficulty in implementation. The study has analyzed the economic performance of organic tomato among smallholder farmers in Lebanon, a Middle Eastern context. The findings show that organic farming has become increasingly expensive primarily due to the inherently high cost of production in Lebanon and the inefficient organization of the organic value chain. Some models and strategies are emerging in developing countries to help adapt organic farming to the context and respond to consumer high demand for organic produce. Two of these are the agro-touristic model and local participatory systems for certification and guarantee.

An agro-tourism model is a blended approach that combines organic and free-range food derived from fresh on-farm produce to touristic activities and locations. Such agro-touristic farms can help promote tourism and sustainable farming methods and provide an enjoyable experience to customers. Agro-touristic places can attract families that wish to spend some time away from the city and those younger generations who wish to know more about farming practices. Indeed, Lebanon has great agro-ecology diversity, from coastal to high altitude areas, with lots of tourist attractions, and a predominantly family based agrarian structure that can support the agro-tourism model. Family farms in Lebanon are small and strongly connected to the country's natural, religious and cultural heritages, and grow a wide variety of crops such as fruit trees, olive trees, cereals, vegetable crops and vines (Marzin et al., Reference Marzin, Bonnet, Bessaoud and Ton-Nu2017). This makes the agro-touristic model a good match to the country's agrarian structure and a better approach to promote the attractiveness of organic farming for small family farms in Lebanon.

Furthermore, other innovative approaches are emerging to maximize the economic, ecological and social benefits of organic farming in developing countries. Due to the difficulty and costs of third-party audit certification, some alternatives are being created in developing countries such as Brazil, India and Mexico, one of the most successful being the ‘PGS’. PGS has never stopped to exist and serve organic producers and consumers eager to maintain local economies and direct, transparent relationships. ‘The verification of the organic quality of a product or process is not concentrated in the hands of a few. All involved in the process of participatory certification have the same level of responsibility and capacity to establish the organic quality of a product or process’ (IFOAM).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Lebanese Ministry of Agriculture for sharing data related to organic agriculture in Lebanon. We also thank Ms Sara Badran for her support (under Undergraduate Research Volunteer Program) in gathering relevant literature.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no potential conflict of interest.