Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) provide a clean and efficient means of generating electrical power from various fuel sources.[ Reference Minh 1 ] However, high operating temperatures (T op > 800 °C) reduce the overpotential arising from standard La1−x Sr x MnO3 cathodes, but increase material costs and shorten cell lifetimes.[ Reference Steele and Heinzel 2 ] Intermediate-temperature (600 °C < T op < 800 °C) SOFCs have potential to overcome these deficiencies but in turn require alternative, mixed ion–electron conducting (MIEC) cathode materials to increase the active region and reduce the cathode overpotential.[ Reference Lu, Hardy, Templeton and Stevenson 3 ] Useful MIEC cathode materials must allow for facile electronic and ionic conductivity.

La1−x Sr x Co1−y Fe y O3 remains the reference MIEC cathode[ Reference Gödickemeier, Sasaki, Gauckler and Riess 4 – Reference Li, Gerdes, Horita and Liu 7 ] although many other cathode materials show promising electrochemical behavior. These include Ba1−x Sr x Co1−y Fe y O3 (BSCF), Sr2Fe2−x Mo x O6 (SFMO), and Sr1−x K x FeO3 (SKFO).[ Reference Shao, Yang, Cong, Dong, Tong and Xiong 8 – Reference Liu, Dong, Xiao, Zhao and Chen 10 ] Many experimental studies have illuminated the structural properties, oxygen transport kinetics, and electrochemical performance of LSCF, BSCF, and SFMO.[ Reference Rembelski, Viricelle, Combemale and Rieu 6 , Reference Liu, Dong, Xiao, Zhao and Chen 10 – Reference Fan and Liu 13 ] Far less is known about SFKO. Hou et al. reported that cathodes of Sr0.9K0.1FeO3 (with a La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.83Mg0.17O3−δ , or LSGM, electrolyte and a Sr2MgMoO6 anode) produced a current density competitive with LSCF at 800 °C.[ Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough 9 ] Repetitive cycling of the cell between open circuit voltage and 0.4 V caused no loss in the observed power density.[ Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough 9 ] Furthermore, SFKO cathodes contain no Co, which improves their cost-effectiveness.[ Reference Hou, Alonso, Rajasekhara, Martínez-Lope, Fernández-Díaz and Goodenough 14 ] Additional studies support the use of Sr0.9K0.1FeO3 as a SOFC cathode material by offering additional evidence of its stability[ Reference Hou, Aguadero, Alonso and Goodenough 15 ] and demonstrating a viable synthesis method for the material.[ Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade 16 ]

The small body of experimental evidence supporting SKFO as an MIEC cathode in SOFC applications suggests that further investigation into this material is warranted.[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

,

Reference Hou, Aguadero, Alonso and Goodenough

15

,

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] First-principles quantum mechanics methods based on Kohn–Sham density functional theory (KS-DFT) have proven useful in providing rational design principles for related materials.[

Reference Pavone, Ritzmann and Carter

17

–

Reference Ritzmann, Dieterich and Carter

26

] Here we provide a DFT study of SKFO (x

K = 0, 0.0625, and 0.125) aimed at answering three questions. First, does potassium substitution (

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

in Kröger–Vink notation[

Reference Kröger, Vink, Seitz and Turnbull

27

]) negatively impact the stability of SKFO? Second, how does the presence of

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

in Kröger–Vink notation[

Reference Kröger, Vink, Seitz and Turnbull

27

]) negatively impact the stability of SKFO? Second, how does the presence of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions cause the electronic structure of SKFO to differ from that of SrFeO3? Finally, do the holes introduced by

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions cause the electronic structure of SKFO to differ from that of SrFeO3? Finally, do the holes introduced by

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects lead to lower oxygen vacancy (

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects lead to lower oxygen vacancy (

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

in Kröger–Vink notation[

Reference Kröger, Vink, Seitz and Turnbull

27

]) formation energies and, thus, higher oxygen vacancy concentrations?

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

in Kröger–Vink notation[

Reference Kröger, Vink, Seitz and Turnbull

27

]) formation energies and, thus, higher oxygen vacancy concentrations?

We address the preceding questions, focusing on the similarities and differences between compositions. This investigation provides fundamental understanding of the effects governing how electron-deficient substitutions in SrFeO3-based materials influence their performance as MIEC cathodes.

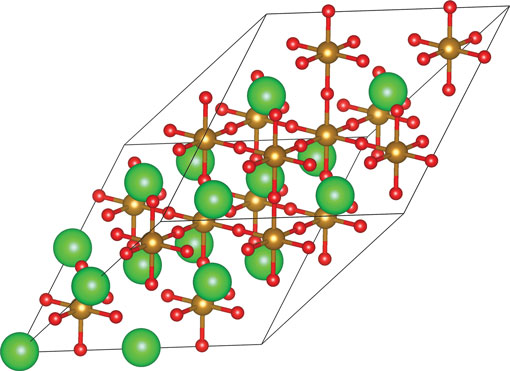

Our KS-DFT calculations of SKFO (x K = 0, 0.0625, and 0.125) were performed using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) version 5.2.2.[ Reference Kresse and Hafner 28 ] Electron exchange and correlation was treated within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew et al.[ Reference Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof 29 ] The 80-atom supercell shown in Fig. 1 was employed for all of the calculations reported. Our total energies are converged to 5 meV/formula unit (full computational details are provided in the Supporting Information).

Figure 1. The 80-atom supercell of SrFeO3 employed here; large green spheres represent Sr atoms, medium gold spheres Fe atoms, and small red spheres oxygen atoms. This supercell was constructed from the primitive perovskite unit cell (a p, b p, c p) with the following lattice vectors (a s, b s, c s): a s = 2a p + 2b p, b s = 2a p + 2c p, and c s = 2b p + 2c p. This figure was created using VESTA.[ Reference Momma and Izumi 30 ]

The stability of SKFO depends on the energy change associated with

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions. Although initial investigations indicate promising stability for this material,[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

,

Reference Hou, Aguadero, Alonso and Goodenough

15

,

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] oxidizing SrFeO3 produces potentially unstable Fe4+ ions. Formal charge analysis suggests that highly unstable Fe5+ ions would also be formed as a result of

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions. Although initial investigations indicate promising stability for this material,[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

,

Reference Hou, Aguadero, Alonso and Goodenough

15

,

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] oxidizing SrFeO3 produces potentially unstable Fe4+ ions. Formal charge analysis suggests that highly unstable Fe5+ ions would also be formed as a result of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions; however, Mössbauer spectra of Sr0.9K0.1FeO3 are completely explained with a mixture of Fe3+ and Fe4+ ions.[

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] Equation (1) presents the chemical process associated with K substitution, transforming SrFeO3 into SKFO. Equation (2) is used to calculate the energy change associated with forming n

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions; however, Mössbauer spectra of Sr0.9K0.1FeO3 are completely explained with a mixture of Fe3+ and Fe4+ ions.[

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] Equation (1) presents the chemical process associated with K substitution, transforming SrFeO3 into SKFO. Equation (2) is used to calculate the energy change associated with forming n

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions (

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions (

![]() $\Delta E_{{\rm f,K}_{{\rm Sr}}^{\rm /}} $

).

$\Delta E_{{\rm f,K}_{{\rm Sr}}^{\rm /}} $

).

In Eq. (2), n is the number of substitutional defects formed to create the appropriate composition (x

K) of SKFO in the 80-atom supercell. We consider the n = 1 case (x

K = 0.0625) and the n = 2 case (x

K = 0.125). SrO (B1 structure) and KO2 are the most stable oxides for each of these cations (see Supporting Information), so these serve as the reference materials in Eq. (1). We calculate the cost per

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

formed using Eq. (2). In this case, E

K present is the total energy of the 80-atom cell with one or two

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

formed using Eq. (2). In this case, E

K present is the total energy of the 80-atom cell with one or two

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects present, E

host is the total energy of SrFeO3 in the 80-atom cell, E

O2

is the energy of the isolated oxygen molecule, E

SrO is the total energy per formula unit of SrO in its ground-state B1 (NaCl) structure, and

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects present, E

host is the total energy of SrFeO3 in the 80-atom cell, E

O2

is the energy of the isolated oxygen molecule, E

SrO is the total energy per formula unit of SrO in its ground-state B1 (NaCl) structure, and

![]() $E_{{\rm KO}_{\rm 2}} $

is the total energy per formula unit of KO2.

$E_{{\rm KO}_{\rm 2}} $

is the total energy per formula unit of KO2.

The formation energies for

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

are reported in Table I. Two key observations arise from the data presented: First, forming

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

are reported in Table I. Two key observations arise from the data presented: First, forming

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects is endothermic. Second, the formation energy per

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects is endothermic. Second, the formation energy per

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

does not change for higher x

K or increased

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

does not change for higher x

K or increased

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

−

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

−

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

separation. The predicted endothermicity raises questions regarding the reported stability of the material.[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

,

Reference Hou, Aguadero, Alonso and Goodenough

15

,

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] However, the calcination temperatures used to synthesize this material (T = 700–1100 °C)[

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] will help stabilize the material as a result of the significant entropic contribution arising from the production of O2 gas in Eq. (1). The second observation indicates that there is no strong driving force for segregation or ordering of

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

separation. The predicted endothermicity raises questions regarding the reported stability of the material.[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

,

Reference Hou, Aguadero, Alonso and Goodenough

15

,

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] However, the calcination temperatures used to synthesize this material (T = 700–1100 °C)[

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] will help stabilize the material as a result of the significant entropic contribution arising from the production of O2 gas in Eq. (1). The second observation indicates that there is no strong driving force for segregation or ordering of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects. This result is consistent with the holes introduced by

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects. This result is consistent with the holes introduced by

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

being highly delocalized (vide infra). We therefore expect that the true crystal will not show any ordering of K+ and Sr2+ ions on the A-site sublattice.

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

being highly delocalized (vide infra). We therefore expect that the true crystal will not show any ordering of K+ and Sr2+ ions on the A-site sublattice.

The perovskite (cubic) phase is preferred when working with SrFeO3-based materials. However, the lattice may undergo a transition to a vacancy-ordered Brownmillerite phase that detrimentally impacts the material's electrical conductivity. We have been unsuccessful in obtaining a reliable optimized structure for the Brownmillerite phase with persistent, non-negligible imaginary frequencies remaining after relaxation. Thus, we cannot currently comment on whether the phase equilibrium between the perovskite and Brownmillerite phases will be altered by the introduction of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

into the material.

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

into the material.

In Fig. 2, we present the projected density of states (PDOS) for SKFO (x

K = 0 and 0.125). Although K is present in these cells, the 4s and 3p states from the K atoms do not have a significant presence near the Fermi level. We therefore focus on the Fe 3d and O 2p states. When x

K = 0.125, we place the two

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects on adjacent sites because the formation energy does not depend on the

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects on adjacent sites because the formation energy does not depend on the

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

−

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

−

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

separation (Table I).

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

separation (Table I).

Figure 2. Projected densities of states (PDOS) for (a) SrFeO3 and (b) Sr0.875K0.125FeO3 in the 80-atom supercell (Fig. 1). Color designations: Fe 3d states (black) and O 2p states (red). By convention, positive (negative) PDOS refer to α (β)-spin channels.

Table I. Formation energies (

![]() $\Delta E_{{\rm f,K}_{{\rm Sr}}^{\rm /}} $

in eV) for

$\Delta E_{{\rm f,K}_{{\rm Sr}}^{\rm /}} $

in eV) for

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutional defects at various concentrations (x

K) and distances between defects (d

K−K in Å).

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutional defects at various concentrations (x

K) and distances between defects (d

K−K in Å).

![]() $\Delta E_{{\rm f,K}_{{\rm Sr}}^{\rm /}} $

values in parentheses include a correction of +0.42 eV for the overbinding of the O2 molecule in DFT–GGA calculations.

$\Delta E_{{\rm f,K}_{{\rm Sr}}^{\rm /}} $

values in parentheses include a correction of +0.42 eV for the overbinding of the O2 molecule in DFT–GGA calculations.

The PDOS contain the same features whether K is present or absent. Both compositions exhibit a pair of broad peaks in the α-spin channel for the Fe 3d states and a strong (mostly unoccupied) Fe 3d peak in the β-spin channel beginning just below the Fermi level. This peak in the β-spin Fe 3d states is the primary cause of the metallic conductivity in SKFO. We also observe that the significant hybridization between the Fe 3d and O 2p states remains when K is present. We therefore can see that the electronic structure of SrFeO3 is essentially preserved up to 12.5%

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

on the A-site sublattice. The PDOS for Sr0.875K0.125FeO3 confirms the metallic conductivity observed experimentally for SKFO above 350 °C.[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

,

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] We cannot evaluate the experimentalists' assertion that a polaronic mechanism governs electronic transport below this temperature.

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

on the A-site sublattice. The PDOS for Sr0.875K0.125FeO3 confirms the metallic conductivity observed experimentally for SKFO above 350 °C.[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

,

Reference Monteiro, Waerenborgh, Kovalevsky, Yaremchenko and Frade

16

] We cannot evaluate the experimentalists' assertion that a polaronic mechanism governs electronic transport below this temperature.

We augment our analysis of the PDOS shown in Fig. 2 by presenting the Fe magnetic moments and Bader charges for all species (Table II) in the same cells and compositions. This process establishes how the SrFeO3 lattice responds to

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

introduction. We find that both the Fe and O sublattices are oxidized in the presence of

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

introduction. We find that both the Fe and O sublattices are oxidized in the presence of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

. Specifically, we observe an increase in the positive Fe Bader charge of 0.02–0.03 e per site for each K atom added (moving right by one column in Table II). Likewise, we observe a decrease in the negative O Bader charge of 0.01–0.02 e per site. The lattice must find a way to accommodate each

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

. Specifically, we observe an increase in the positive Fe Bader charge of 0.02–0.03 e per site for each K atom added (moving right by one column in Table II). Likewise, we observe a decrease in the negative O Bader charge of 0.01–0.02 e per site. The lattice must find a way to accommodate each

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

that renders 0.78 e (q

Sr − q

K in the third and fourth rows of data in Table II) no longer available to the lattice. The extent of each hole is obtained as the difference between the Sr and K Bader charges, which is consistent across both cells. The first

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

that renders 0.78 e (q

Sr − q

K in the third and fourth rows of data in Table II) no longer available to the lattice. The extent of each hole is obtained as the difference between the Sr and K Bader charges, which is consistent across both cells. The first

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

oxidizes the Fe sublattice by 0.30 e and the O sublattice by 0.43 e, while the second

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

oxidizes the Fe sublattice by 0.30 e and the O sublattice by 0.43 e, while the second

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

oxidizes the Fe sublattice by 0.40 e and the O sublattice by 0.37 e. The small remainders of 0.05 and 0.01 e required to make the total oxidation 0.78 e (vide supra) for the formation of the first and second

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

oxidizes the Fe sublattice by 0.40 e and the O sublattice by 0.37 e. The small remainders of 0.05 and 0.01 e required to make the total oxidation 0.78 e (vide supra) for the formation of the first and second

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

, respectively, are taken from the Sr sublattice and produce a negligible effect on the average Sr Bader charge.

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

, respectively, are taken from the Sr sublattice and produce a negligible effect on the average Sr Bader charge.

Table II. Fe magnetic moments (μ Fe in μ B) and Bader charges (q Fe, q Sr, q K, and q O in e) for SKFO with x K = 0, 0.0625, and 0.125.

From the preceding analysis, we conclude that the holes introduced by

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutional defects are delocalized across both Fe and O sublattices. This conclusion is consistent with the presented PDOS (Fig. 2), which show significant hybridization between the O 2p and Fe 3d states.

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutional defects are delocalized across both Fe and O sublattices. This conclusion is consistent with the presented PDOS (Fig. 2), which show significant hybridization between the O 2p and Fe 3d states.

The motivation for choosing SKFO over SrFeO3 is that the introduction of holes should lower the

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energy by promoting reduction of the lattice, leading to higher

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energy by promoting reduction of the lattice, leading to higher

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

concentrations and improved oxide-ion diffusivity. However, we must determine whether or not this hypothesis holds. If so, to what extent do the holes from

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

concentrations and improved oxide-ion diffusivity. However, we must determine whether or not this hypothesis holds. If so, to what extent do the holes from

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

reduce the

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

reduce the

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energy (ΔE

f,vac)? We address these questions by computing the ΔE

f,vac in the 80-atom supercell (Fig. 1) with one

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energy (ΔE

f,vac)? We address these questions by computing the ΔE

f,vac in the 80-atom supercell (Fig. 1) with one

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

present. Whenever two defects (e.g., one

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

present. Whenever two defects (e.g., one

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

and one

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

and one

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

) are present, the proximity of these defects may impact the defect formation energies. However, our previous discussion of

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

) are present, the proximity of these defects may impact the defect formation energies. However, our previous discussion of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects (vide supra) that produce delocalized positive charge in the lattice suggests that proximity between defects will have a negligible effect on ΔE

f,vac.

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

defects (vide supra) that produce delocalized positive charge in the lattice suggests that proximity between defects will have a negligible effect on ΔE

f,vac.

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation in SKFO is governed by Eq. (3), where δ corresponds to one

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation in SKFO is governed by Eq. (3), where δ corresponds to one

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

being formed in the 80-atom supercell. This leads to the expression for ΔE

f,vac given in Eq. (4).

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

being formed in the 80-atom supercell. This leads to the expression for ΔE

f,vac given in Eq. (4).

In Eq. (4), E

defective is the energy of the supercell with a

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

present,

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

present,

![]() $E_{{\rm O}_{\rm 2}} $

is the energy of the isolated oxygen molecule, and E

host is the energy of the supercell without a

$E_{{\rm O}_{\rm 2}} $

is the energy of the isolated oxygen molecule, and E

host is the energy of the supercell without a

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

defect. The thermal contributions, both enthalpic and entropic, from the host and defective solids are expected to be comparable and therefore can be neglected (e.g., we computed the thermal contribution to ΔG

f,vac from the solids to be only 0.02 eV at 700 °C in LaFeO3).[

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

20

,

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

21

] We include thermal contributions from the O2 molecule because they contribute significantly at SOFC operating temperatures.[

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

20

,

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

21

] While the free energy (ΔG

f,vac) governs the

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

defect. The thermal contributions, both enthalpic and entropic, from the host and defective solids are expected to be comparable and therefore can be neglected (e.g., we computed the thermal contribution to ΔG

f,vac from the solids to be only 0.02 eV at 700 °C in LaFeO3).[

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

20

,

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

21

] We include thermal contributions from the O2 molecule because they contribute significantly at SOFC operating temperatures.[

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

20

,

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

21

] While the free energy (ΔG

f,vac) governs the

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

concentration, our assumption about the negligible thermal contributions means that trends in ΔE

f,vac should mirror those in ΔG

f,vac.

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

concentration, our assumption about the negligible thermal contributions means that trends in ΔE

f,vac should mirror those in ΔG

f,vac.

The

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energies for various

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energies for various

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

−

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

−

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

distances are presented in Table III. The data confirm our expectation that there is no significant effect from the proximity of the two defects. This result is consistent with the metallic nature of SKFO. The

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

distances are presented in Table III. The data confirm our expectation that there is no significant effect from the proximity of the two defects. This result is consistent with the metallic nature of SKFO. The

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energies are computed using the optimized geometries containing both the

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energies are computed using the optimized geometries containing both the

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

and

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

and

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

defects.

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

defects.

Table III. Uncorrected

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energies (∆E

f,vac in eV) and free energies [∆G

f,vac (700 °C) in eV] in Sr0.9375K0.0625FeO3 as a function of

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation energies (∆E

f,vac in eV) and free energies [∆G

f,vac (700 °C) in eV] in Sr0.9375K0.0625FeO3 as a function of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

−

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

−

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

separation (

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

separation (

![]() $d_{{\rm K}_{{\rm Sr}}^{\rm /} - {\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet}} \,$

in Å). Corrected ∆E

f,vac and ∆G

f,vac values are reported in parentheses (corrected for the DFT–GGA error for O2). ∆E

f,vac is 1.27 (1.69) eV for SrFeO3 in the same supercell.

$d_{{\rm K}_{{\rm Sr}}^{\rm /} - {\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet}} \,$

in Å). Corrected ∆E

f,vac and ∆G

f,vac values are reported in parentheses (corrected for the DFT–GGA error for O2). ∆E

f,vac is 1.27 (1.69) eV for SrFeO3 in the same supercell.

The uncorrected ∆E

f,vac values in Table III (1.07–1.13 eV) must then be compared with the uncorrected ∆E

f,vac value (1.27 eV) obtained in the same supercell in the absence of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

. This decrease in ∆E

f,vac (~0.2 eV) indicates that the

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

. This decrease in ∆E

f,vac (~0.2 eV) indicates that the

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation is made easier by charge compensation. The ∆G

f,vac values computed without the O2 bond dissociation energy correction indicate that our chosen

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation is made easier by charge compensation. The ∆G

f,vac values computed without the O2 bond dissociation energy correction indicate that our chosen

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

concentration (δ = 0.0625) is close to the expected concentration. However, the corrected values are positive, indicating that we should predict a

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

concentration (δ = 0.0625) is close to the expected concentration. However, the corrected values are positive, indicating that we should predict a

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

concentration for x

K = 0.0625 far lower than the concentration we employed. This effect must be balanced against the fact that larger x

K concentrations (e.g., x

K = 0.125) not considered here contain far more holes and may lead to lower ∆G

f,vac values. The limitation of our preliminary study is that we have only investigated the scenario where x

K and δ are equal to one another. The material, as synthesized by Hou et al., has δ = 0.20 at 800 °C.[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

] Exploring different ratios of

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

concentration for x

K = 0.0625 far lower than the concentration we employed. This effect must be balanced against the fact that larger x

K concentrations (e.g., x

K = 0.125) not considered here contain far more holes and may lead to lower ∆G

f,vac values. The limitation of our preliminary study is that we have only investigated the scenario where x

K and δ are equal to one another. The material, as synthesized by Hou et al., has δ = 0.20 at 800 °C.[

Reference Hou, Alonso and Goodenough

9

] Exploring different ratios of

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

-to-

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

-to-

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

is beyond the scope of this work; however, such an investigation should yield insight into the

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

is beyond the scope of this work; however, such an investigation should yield insight into the

![]() ${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation process when more holes are present in the supercell.

${\rm V}_{\rm O}^{ \bullet \bullet} $

formation process when more holes are present in the supercell.

The preceding analysis has successfully answered the questions we posed at the start of this work. We find that potassium substitution is endothermic in SKFO raising questions about the long-term stability of this material for use in SOFC applications. Endothermic

![]() ${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions may lead to phase instability at lower operating temperatures where the entropic driving force associated with producing O2 (g) does not outweigh the energetic cost of forming the substitutional defect. Experimentalists should determine whether the endothermicity of these substitutions necessitates high-temperature SOFC operation. Our oxygen vacancy formation energies differ from previous studies of electron-deficient substitutions (e.g., Sr2+ for La3+ in La1−x

Sr

x

FeO3−δ

)[

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

20

] in related materials. Specifically, the charge compensation effect in La1−x

Sr

x

FeO3−δ

leads to dramatic drop of ~3.5 eV in ΔG

f,vac when increasing x

Sr from 0 to 0.25. In contrast, we find only a small decrease of ~0.2 eV for ΔG

f,vac in SKFO when x

K is increased from 0 to 0.0625. Charge compensation between holes introduced by Sr substitution and oxygen vacancies in La1−x

Sr

x

FeO3−δ

enables the Fe ions to retain their Fe3+ (high spin d

5) configuration.[

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

20

] The same effect in SKFO plays a smaller role (~0.2 eV) because the holes are delocalized (vide supra) and the Fe ions remain trapped between the 3+ and the (less stable) 4+ oxidation states.

${\rm K}_{\rm Sr}^/ $

substitutions may lead to phase instability at lower operating temperatures where the entropic driving force associated with producing O2 (g) does not outweigh the energetic cost of forming the substitutional defect. Experimentalists should determine whether the endothermicity of these substitutions necessitates high-temperature SOFC operation. Our oxygen vacancy formation energies differ from previous studies of electron-deficient substitutions (e.g., Sr2+ for La3+ in La1−x

Sr

x

FeO3−δ

)[

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

20

] in related materials. Specifically, the charge compensation effect in La1−x

Sr

x

FeO3−δ

leads to dramatic drop of ~3.5 eV in ΔG

f,vac when increasing x

Sr from 0 to 0.25. In contrast, we find only a small decrease of ~0.2 eV for ΔG

f,vac in SKFO when x

K is increased from 0 to 0.0625. Charge compensation between holes introduced by Sr substitution and oxygen vacancies in La1−x

Sr

x

FeO3−δ

enables the Fe ions to retain their Fe3+ (high spin d

5) configuration.[

Reference Ritzmann, Muñoz-García, Pavone, Keith and Carter

20

] The same effect in SKFO plays a smaller role (~0.2 eV) because the holes are delocalized (vide supra) and the Fe ions remain trapped between the 3+ and the (less stable) 4+ oxidation states.

We have presented a DFT-based analysis of SKFO (x K = 0, 0.0625, and 0.125). Potassium substitutions introduce more Fe4+ ions by oxidizing the Fe sublattice. However, these substitutions are endothermic, suggesting that SKFO may be unstable at the desired lower operating temperatures. The presence of potassium in SKFO is predicted to lower the oxygen vacancy formation energy by ~0.20 eV, leading to the expectation of somewhat higher oxygen vacancy concentrations and improved oxygen ion conductivity compared to SrFeO3. This increase in the oxygen vacancy concentration comes without substantial alterations in the electronic structure when SKFO and SrFeO3 are compared. Further study of this material will determine its suitability for SOFC applications and may lead to improved SOFC devices.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1557/mrc.2016.23.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michele Pavone, Ana Belen Muñoz-García, and John Keith for helpful discussions in the course of this study. We thank Nari Baughman for help in revising this Communication. HeteroFoaM, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under the award DE-SC0001061 provided funding for this work. The simulations carried out in this work were performed on computational resources supported by the Princeton Institute for Computational Science and Engineering (PICSciE) and the Office of Information Technology's High Performance Computing Center at Princeton University.