1. Background

In the context of the Vienna World Exposition of 1873, a group of art historians came together for the first time for an ‘international’ conference. It was not however until 1893 that a second gathering of this kind was convened at the GNM [Germanisches Nationalmuseum] in Nuremberg. There it was decided to meet regularly in the future, in order to intensify the exchange of information about current scholarship at an international level.

The early conferences had no fixed themes. The emphasis was on exchange about recent research. At first, interest focused mainly on the art of Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany. After 1918, however, there was greater attention to Europe as a whole, and then, after 1945, to the United States as well. This was reflected in the overall themes of the congresses and the titles of the papers presented.

Who or what is ‘CIHA’? CIHA is the abbreviation for both the ‘Comité’ and the ‘Congrès International d’Histoire de l’Art.’ For a moderate annual membership fee, all nations with art historians in their universities, museums, or heritage commissions can name as many as four delegates to the CIHA-Committee. The respective nations are then members of CIHA; there are no private memberships, as in such other international organizations as ICOM or ICOMOS. The Committee is under the auspices of UNESCO. On the advice of the board, it chooses the venue for the next congress. A necessary prerequisite is an invitation by the representatives of a member nation, as well as a proposal for an overall theme for the congress. That theme must be internationally – or in today's terms, globally – relevant and must interlink a broad spectrum of media and periods of art history. And last but not least, the financial feasibility of the undertaking has to be demonstrated. After a congress has been held, its president normally serves as president of the CIHA for the next four years.

In recent years, the orientation of the congresses has shifted markedly. And art history as an academic discipline is also in the process of globalizing. However, the fact that the world consists of five continents has only recently become apparent. The first non-European venues were Washington in 1986 and Montreal in 2004. And the most recent CIHA Congress, in 2008 in Melbourne, was the first to take place in the southern hemisphere. It is certain that in the near future CIHA congresses will be convened at venues in Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. There are already vigorous contacts with national committees in those regions, as well as many proposals for smaller annual meetings to bridge the four-year intervals between major international congresses.

Traditional academic art history has always been – and is, to this day – primarily oriented towards Western art (Figure 1). In Europe, global art appreciation is for the most part limited to so-called ‘primitive art’, for which there is a lucrative market, or to contemporary art that is largely subject to Western influence. Only recently, for example, the first German professorship for African art history was established at the Free University in Berlin. American scholarship on the other hand has a long tradition of regard for the art of other continents. The opportunity inherent in globalization is that, when we abandon our Western-oriented and frequently arrogant ‘navel-gazing’ and incorporate into the art-historical canon works of art from what used to be known as the ‘third world,’ we will be vastly extending our narrow academic horizons. When we look at Asian sculpture, for example, we will quickly recognize that it has already reached an artistic level that is, in many cases, far superior to its European counterparts.

Figure 1. Nuremberg, GNM. Albrecht Duerer: His mother (ca. 1490).

Under the theme of ‘Crossing Cultures’ the 2008 Melbourne Congress took a first step in this direction by addressing such topics as the convergence and interchange of Western art in Australia with the indigenous art of the Aboriginal people.

2. The Nuremberg Congress

The Congress being planned for Nuremberg in 2012 (www.ciha2012.de) will go a step further. In the 21 individual sections (with a total of up to 400 papers), the topics discussed against the background of contemporary developments will, of course, include many ‘classical’ art-historical issues. The intention of the Committee on this occasion, however, is to transcend the usual categorical limitations. As a fundamental principle, no section should have a single genre, period, or continent as its topic.

The theme of the 2012 CIHA Congress in Nuremberg is ‘The Challenge of the Object’. Because, in an age of globalization and the steadily increasing virtualization of objects, the place of the art-object itself becomes art history's greatest challenge. In a globalized and technological age, the art-object as the subject matter of art history demands even closer scrutiny. The frequently-cited ‘iconic turn’ with its immense flood of technically generated images focuses new and acute attention on the place of the object within this spectrum. The Nuremberg Congress will seek to stimulate discussion about the object from a global and inter-medial perspective and to vigorously encourage a new conceptualization of the object and the original that will respond to contemporary challenges and provide a more comprehensive perspective than is offered by the traditional point of view.

On the one hand, we are observing the disappearance of the actual art work into virtual space, but on the other, there is a renewed fascination with the aura of the original – as witnessed by the steadily lengthening queues in front of the Mona Lisa and other such iconic ‘highlights’ of the artistic world (Figure 2). We are furthermore currently seeing a globalization of the art system combined with a multiplication of both art production and art consumption. These trends confront art history with the challenge of developing a new set of academic and theoretical tools that will extend far beyond the Western perspective that has dominated the discipline until now.

Figure 2. Paris, Louvre. Mona Lisa.

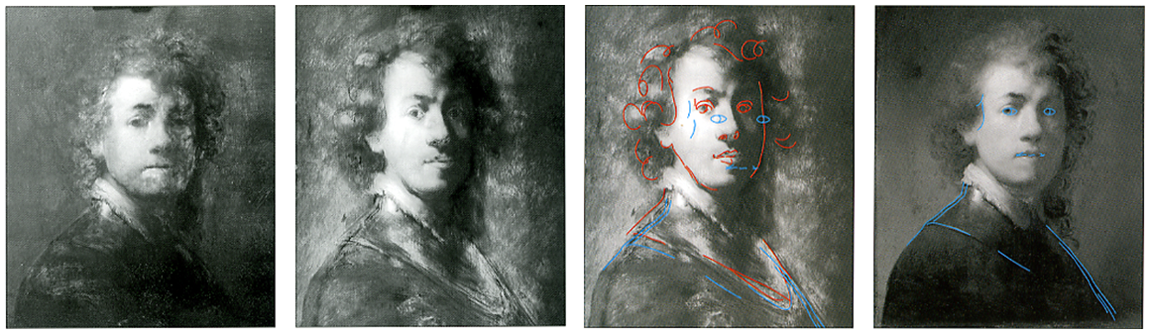

For a congress that is to be hosted by a museum, there could hardly be a more obvious and appropriate theme than the object and the original. To be sure, the art-object is fundamental to art-historical research, but only for the scholar working in a museum or gallery is the immediate confrontation with the work as a physical object a matter of daily course. In contrast, at the university, access to the physical object is generally far more limited (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Rembrandt, Self-portraits.

For this reason, university research normally confines itself to dealing with the style and pictorial content of an art-work, especially in paintings, sculpture and the graphic arts, and normally refrains from dealing with matters of originality, original condition, and state of preservation of the work of art under consideration. Thus an academic dissertation may be devoted to the subject of a presumed self-portrait of Dürer and may assert hypotheses about its dating without involving any critical examination of the original portrait itself, even though museum scholars who are far more familiar with drawings by Dürer have long since eliminated that work from the œuvre of the artist. On the other hand, a museum's inventory-catalogue can undertake an in-depth ‘autopsy’ of a work of art without reaching any farther-reaching conclusions. To be sure, such defects – which I am simply anonymizing but not inventing – represent the extreme, but art history's problem is manifested by the absence of any widespread criticism of such shortcomings.

For example, how much intellectual energy was invested by art historians in explaining the fly on Dürer's Feast of the Rose Garlands (Prague) before it was recognized that this motif was a later addition – thereby eliminating the basis for a simple interpretation?

But even in cases where the departure point for deliberations is the actual art-object, the focus is frequently not on the original – or to put it more generally, the material object – but rather on a photo of the object. It can even occur that appraisals of the originality of an artwork are occasionally prepared – even by prominent art historians – on the basis of ‘excellent photographs’ (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Rembrandt, Self-portrait (GNM).

A central question comes up about the meaning of the object, especially of the ‘original’ object, in a virtual age. Art historians have long conducted their research on the basis of photos, reproductive prints, or casts and not on the original object itself. And now this object threatens to vanish entirely from sight and to be replaced by a digital image. Which of the hundreds of illustrations of the Mona Lisa accessible on the Internet comes closest to the original (Figures 5 and 6)? What opportunity do researchers have today to see the original at all, particularly when sponsors influence its presentation and – in the case of the Sistine Chapel – severely restrict research options by permitting only the use of the sponsor's photographic images?

Figure 5. Mona Lisa.

Figure 6. Mona Lisa.

The virtualization of the object stands in stark contrast to the aura of the original. What will be the effect of this ‘disappearance of the object’ in the 21st century? How does this phenomenon influence the history of art? How does it influence the appreciation of art by the general public? And finally, how is this aspect thematized by contemporary artists (Figures 7 and 8)? One section of the Congress will be devoted to this basic question of the concept of the ‘original’ both in relation to copies and reproductions and also with regard to alterations and imitations.

Figure 7. Francis Alys, Fabiola. An investigation. Los Angeles, LACMA, Department of Modern Art.

Figure 8. Ben Vautier, Rien. Schwerin, Landesmuseum, Department of Modern Art.

Bringing together the various methods and approaches is obviously a critical task. The 2012 CIHA Congress seeks to provide a fundamental starting point and basic impetus for an intensified dialogue among colleagues from every continent, nation, and discipline. The sections of the Congress will address various aspects of the topic ‘object.’ Fundamental issues will be the role of the art-object in art history and the way such objects are treated in relation to the methods of research and documentation. At opposite ends of the spectrum are the issues of ‘The art market and the original’ and ‘The vanishing original in a virtual age,’ particularly as a result of the Internet. The latter question, by the way, also raises the issue of rights to images of an art work.

A ‘theory of the object’ has aspects that extend much farther than the distinction between the original and any virtual representation of it. For example: as art historians, we regard a statue of the Madonna in a museum from the point of view of its style, we consider the arrangement of its folds and polychromy, we ask after the original setting and the patron who commissioned it. For the devout Catholic, however, the same sculpture may be and remain an object of veneration that has been removed from its proper context and may even seem to him to be inappropriately displayed (Figure 9) in such a museum setting.

Figure 9. Nuremberg, GNM. Madonna (ca. 1200).

At the same time, observing other cultures and their approach to the object, both as a thing and as a concept, can sharpen the eye of European and North American art historians as well, enabling access to an ‘extended’ concept of the object. For example, the concept of the ‘object as subject’ in African or Native American cultures is reminiscent of medieval reliquary cult and portraiture practice in early modern Europe. Contemporary art forms like performances and ‘social sculpture’ find historical parallels in such ephemeral works of art as fireworks, festival decorations, or ‘living pictures’/‘tableaux vivants.’ In the same way, they survive only through secondary documentation – in photos, videos, prints, or written reports. As with video or internet art, these forms challenge us to ask: what is the work of art, the object? What is the ‘original?’

Another section will deal with the relationship of religions to the art-object and thus also with the problem of objects of religious veneration that are extracted from their original context and moved into museums. Related to that is the question of the object as subject. The object in the museum and the treatment of world heritage items illuminate widely differing forms of treatment and approaches to representation of cultural identity. ‘Viewing others and the views of others’ explores the issue of how cultures that are unfamiliar with each other react to each other's material culture (Figure 10). Western knowledge of African or Asian art, for example, is often influenced by Western connoisseurship of past centuries. But in these domains the question of restitution can also come up. The historical documentation of the object and the ‘archaeology of the tangible object’ deal with the history of the preserved artefact and its immediate investigation.

Figure 10. Kyoto (Japan), Temple.

Contrasting perceptions of the art-object are even more likely to be the case when the cultural heritage of Africa, Pre-Columbian America, Asia or Oceania, are exhibited out of their original contexts. Here we are dealing with works which, for members of those cultures, may have lost none of their original sacral significance. Their presentation is likely to strike them as totally inappropriate. And misplaced, as well – namely in a Western museum – completely detached from their cultural and ritual context (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Ganesh. Asian sculpture with donation box. San Francisco, Asian Art Museum.

In politically or religiously motivated iconoclasm, the boundary between art and reality – between historical works of art that are associated with real or assumed values and the currently prevailing values of contemporary rulers and factions – is suspended. The destruction of works of art becomes an expression of a particular cultural attitude and at the same time, a gauge of political (in)tolerance. The topic of the section ‘Famous places’ is devoted to the region where the Congress is taking place. It will deal with places associated with political and socio-political events and the way they are treated by the history of art.

What is the significance of an object in architectural form? In Europe, we have developed strategies to protect ‘original substance’ – although the truth is that, in the face of short-sighted economic interests, we almost always end up on the losers’ side in the battle for historic preservation. For us, the demolition of the Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady, Figure 12) in Dresden would amount to a complete and total loss. And a similar but possibly somewhat larger structure erected a short distance away would be seen, at best, a caricature. In the Orient, the total replacement of buildings is perhaps not the rule, but it does occur quite frequently… and then, often after only a generation or two. The ‘15th century South Gate’ in Beijing/Peking was rebuilt, along with its ‘historic’ intersection, 40 years after being demolished, while the historic road between this gate and the gate at the Imperial Palace is currently being torn up.

Figure 12. Frauenkirche, Dresden. The reconstructed church.

The same question arises in a different way in the case of restored or recreated works of art, whether paintings or architecture. Modern Asian temples that are (ostensibly) exact copies of earlier original structures acquire their aura through their external form and the continuity of location. The temple in Nanchang, for example (Figure 13), a populous city in central China, has predecessors going back to the 8th century. The present building, however, was constructed entirely anew, on a grander scale than ever before, after 1973. Inside there are broad concrete steps and an elevator; no part of the structure is more than 30 years old. The outer form, however, suggests a much older building.

Figure 13. Nangchang (China), reconstructed medieval temple.

But issues of an entirely different nature are also topical. The globalization of our artistic perspectives focuses the attention of the history of art on trans- and intercontinental cultural connections. Such interconnections have always existed, although in any given era they may not necessarily have played a major role.

Nonetheless, modern scholarship frequently underestimates the significance of such exchange. I don’t mean to suggest that art has been ‘networked’ worldwide since the beginning of history just because this issue is currently fashionable. But it is important to note that there was, for example, regular contact between central Europe and East Asia by the 13th century and that in the late 15th century there was widespread knowledge about the west coast of Africa. This is demonstrated by the ‘Behaim Globe’ (GNM, Nuremberg) that was produced in Nuremberg on the basis of Portuguese maps, while the first representation of the world in the form of a globe was ‘made in Nuremberg’ in 1492. Such contacts and interconnections need to be studied – and not only in a European context! This is a future-oriented research project, especially in view of the fact that until now non-European art history has usually been treated in Europe in separate and unrelated disciplines. At the same time, attention should also be drawn to the great achievements of non-European art. In some regards and especially during the European Middle Ages, Far Eastern art, for example, was far more highly developed – by common European standards – than the art of Europe.

In the summer of 2012, the GNM will present a great exhibition devoted to the early work of Albrecht Dürer. Since 2007, an extensive research project has been under way to examine Dürer's entire œuvre. The especially uncertain early work is the subject of the first exhibition. The section ‘Dürer and the Age of Dürer as an example of European cultural exchange’ is related to this exhibition in parallel with the CIHA Congress.

3. Nuremberg as the congress venue

Nuremberg was established as the site of the GNM in 1857 (Figure 14). This was because of its historic importance as a central metropolis of the Holy Roman Empire and the city to which, during the late Middle Ages, every newly-elected king [emperor] convened his first imperial diet. Nuremberg's greatness derived from the city itself, its central location and excellent contacts throughout Europe, and in no small measure from the creative ingenuity of its citizens.

Figure 14. Nuremberg, GNM, new wing (‘Galerie’).

The Germanisches Nationalmuseum is today the largest museum of German art and culture and, as an internationally recognized research institution, is financed by both the Federal Republic of Germany and its 16 states (Länder). The GNM incorporates the largest historico-cultural library of the German-speaking world and the Fine Arts Archives (Deutsches Kunstarchiv). Its incomparable stores of exceptional art and artisanship afford a panoramic overview of the cultural history of German-speaking Central Europe. In addition to all facets of art history, the museum houses historical musical instruments, clothing, weapons of the Middle Ages and of modern times, as well as scientific instruments and objects of the prehistoric and early historical periods. The GNM arranges its collections with a historico-cultural focus, namely in a chronological and thematic way. The different genres are not exhibited separately, like in an art gallery, but are presented together (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Nuremberg, GNM, the street of the Human Rights (Dani Karavan) and the Dalai Lama.

4. Excursions and program-related events

A program of excursions to important destinations in Germany and particularly in southern Germany will be offered in conjunction with the Congress. Included in the program will be such major architectural highlights as Bamberg's Romanesque cathedral, the Gothic cathedral in Regensburg, and the Baroque pilgrimage church ‘Vierzehnheiligen,’ as well as notable museums outside of Nuremberg and such world-famous attractions as the 19th-century Castle Neuschwanstein.

The 2012 CIHA Congress in Nuremberg is devoted to ‘The Challenge of the Object.’ Within the framework of the course program ‘Tours and Talks,’ a post-graduate program under the theme of ‘Get in Touch – Objects, Places, People’ will provide a unique opportunity for hands-on involvement with the object via contact with originals in the museums of Nuremberg, with their original settings and with specialists (curators, conservators, curators of monuments, artists) who are directly involved with these objects. At the same time, it will also serve to promote exchange among participants, as will the presentation of individual research results in public poster sessions and summaries of award-winning poster presentations at the Congress Center. As part of the effort to encourage international contact between post-graduate students, internal welcome and farewell gatherings are also planned.