Rising rates of adolescent suicide fatality and attempts represent a national public health priority. Extant theories primarily seek to understand the transition from suicidal ideation to attempt (i.e., ideation-to-action frameworks, see below for more detail). However, suicidal ideation is poorly understood in the existing suicide literature (Jobes et al., Reference Jobes, Mandel, Kleiman, Bryan, Johnson and Joiner2024; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Rosario-Williams, Kelly, Macrynikola and Sullivan2022) and most attention has been placed on a sole cognition: active suicidal ideation (i.e., the serious consideration of killing one’s self). This theoretical emphasis has support in the empirical literature, as active suicidal ideation during adolescence is a relatively strong predictor of future suicide attempts (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Kingsbury, Warner, Landry, Clayborne, Islam and Colman2023; Castellví et al., Reference Castellví, Lucas-Romero, Miranda-Mendizábal, Parés-Badell, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Roca, Rodríguez-Marín, Rodríguez-Jimenez, Soto-Sanz and Alonso2017). Even so, it is estimated that only a third of all adolescents who actively consider suicide make an attempt (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Franz, Guzmán, Glenn, C., Kleiman and Nock2018; Nock et al., Reference Nock, Green, Hwang, McLaughlin, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2013), with a recent meta-analysis and systematic review indicating a great deal of variability in the extent to which active suicidal ideation during adolescence predicts attempted suicide (effect sizes range from 0.57 to 15.94; Castellví et al., Reference Castellví, Lucas-Romero, Miranda-Mendizábal, Parés-Badell, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Roca, Rodríguez-Marín, Rodríguez-Jimenez, Soto-Sanz and Alonso2017).

The consideration of additional cognitions may prove fruitful in explaining variance in attempted suicide. Indeed, a large body of research finds that adolescence is not only - a period of heightened onset and prevalence of active and passive suicidal ideation (the desire to no longer be alive), but also a time for: (a) other, non-suicidal cognitions about mortality, and (b) cognitions about life. Yet existing theories developed for the purpose of articulating the pathways from ideation to attempt have not integrated these well-established non-suicidal cognitions during adolescence into a conceptual model to guide research and the prevention of suicide, nor have they considered their content, timing, or mental imagery in relation to suicidal ideations.

It is important to note that there are both limitations and benefits in focusing on adolescence in conceptualizing how cognition shapes behavior. On the one hand, while suicide fatality was the second leading cause of death for adolescents for the past decade, it accounts for a relatively low absolute number of deaths: approximately two to three thousand per year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023a), which underscores adolescence as a time of optimal health and wellbeing. On the other hand, adolescence is a period in which an adolescent’s actions and the contexts in which they are embedded have long-term implications for adulthood. Notably, nearly 70% percent of all global premature adult mortality is associated with processes that begin in adolescence (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Afifi, Bearinger, Blakemore, Dick, Ezeh and Patton2012), in tandem with the median onset of mental illness (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Shin, Kirkbride, Jones, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2022), sexual activity (Guttmacher Institute, Reference Institute2019), and drug use (Alcover & Thompson, Reference Alcover and Thompson2020). Less is known about how cognitions that are formed during adolescence shape thoughts and behavior across the life course. What we do know is that much of the active suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior that occurs after adolescence are estimated to be reoccurring cognitions (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Kingsbury, Warner, Landry, Clayborne, Islam and Colman2023) and reattempts (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Kingsbury, Warner, Landry, Clayborne, Islam and Colman2023; Goldston et al., Reference Goldston, Daniel, Erkanli, Heilbron, Doyle, Weller, Sapyta, Mayfield and Faulkner2015), respectively. Taken together, adolescence represents an important period for the prevention of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Morris-Perez et al., Reference Morris-Perez, Abenavoli, Benzekri, Rosenbach-Jordan and Boccieri2023).

In this paper, we review existing theories of suicide and the literature on the characteristics of suicidal ideations and non-suicidal thoughts adolescents have about (1) their life and (2) their death that may co-occur with active and passive suicidal ideation, that have received less attention in the field of adolescent suicidology, and that may have implications for the prevention of suicide in adolescence (and potentially across the life course). The result of our review is a conceptual model that we entitle the “cognition-to-action” framework, that is squarely developmental in its conceptualization and designed to inform primary prevention efforts. We conclude with hypotheses that emerge from the framework, as well as future directions for further research to test and refine this theory.

Current paradigms of suicide: active and passive ideations as key precursors to attempts

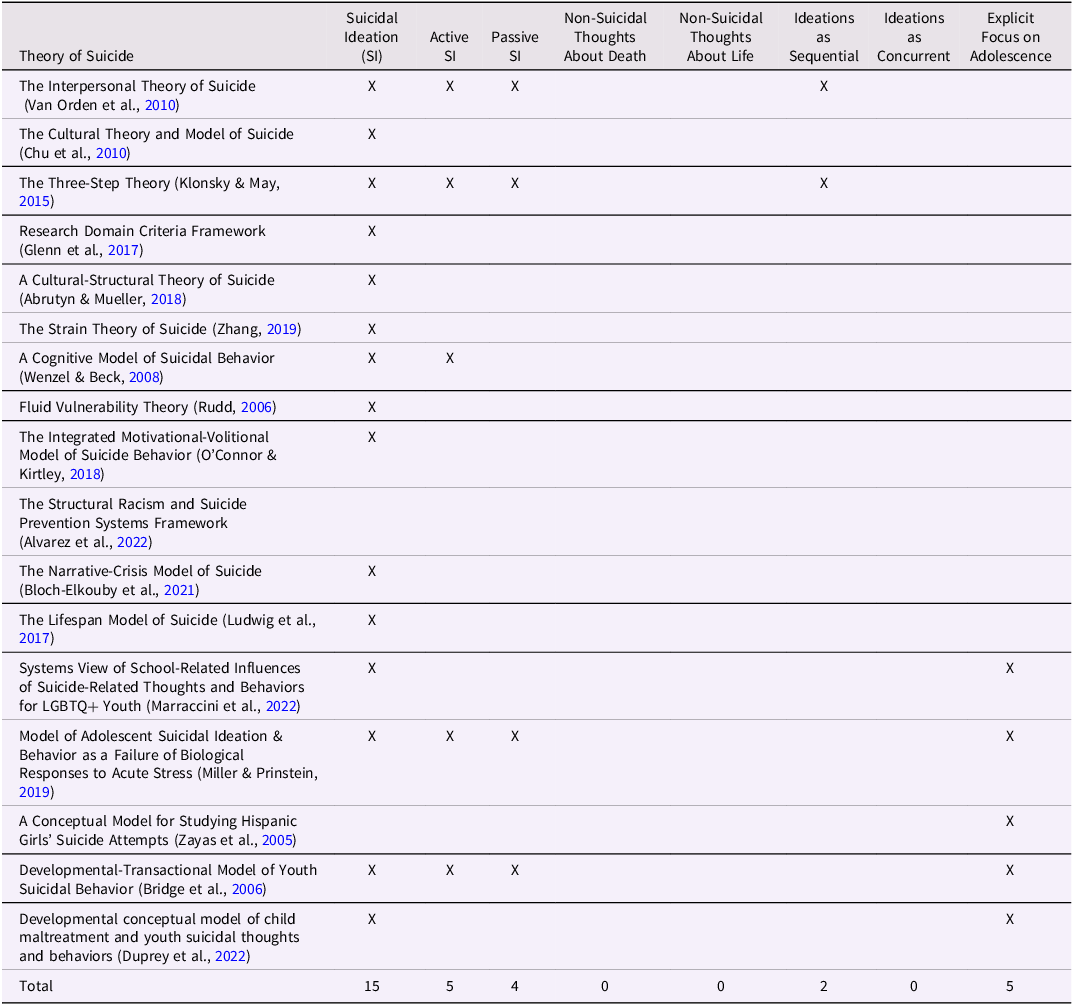

Current paradigms of suicide have importantly sought to understand the transition from the consideration of suicide to attempted suicide. Of the 17 theories/frameworks of suicide that have been published in the past two decades (see Appendix), the majority (>88%) consider suicidal ideation, most often as either a mediator of the relationship between psychological pain and attempted suicide (Duprey et al., Reference Duprey, Handley, Wyman, Ross, Cerulli and Oshri2022; Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015) or as a joint outcome with behavior (Bloch-Elkouby et al., Reference Bloch-Elkouby, Yanez, Chennapragada, Richards, Cohen and Galynker2021; Miller & Prinstein, Reference Miller and Prinstein2019). In particular, the field has largely relied on “ideation-to-action frameworks” including the interpersonal-psychological theory (Wolford-Clevenger et al., Reference Wolford-Clevenger, Stuart, Elledge, McNulty and Spirito2020), the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010), the integrated motivational-volitional model (O’Connor, Reference O’Connor2011), the fluid vulnerability theory (Rudd, Reference Rudd and Ellis2006), and the three-step model of suicide (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). These frameworks typically treat the onset of active suicidal ideation and the escalation of ideation to attempt as separate phenomena with distinct predictors and moderators. For example, psychological pain and hopelessness are key predictors in the onset of suicidal ideation, but acquired capability and burdensomeness have been named as key elements in transitioning from ideation to attempt (Duprey et al., Reference Duprey, Handley, Wyman, Ross, Cerulli and Oshri2022; Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015; O’Connor & Kirtley, Reference O’Connor and Kirtley2018; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010). This work has been critically important in building a nuanced understanding of the escalation to suicidal actions and has been foundational to guiding a number of highly promising prevention strategies in adolescence and across the life span.

Two theories have especially moved the field forward by considering ideation as two qualitatively distinct suicide-related thoughts – active suicidal ideation (i.e., the serious consideration of killing one’s self) and passive ideation (i.e., the desire to no longer be alive; Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010).

Active suicidal ideation

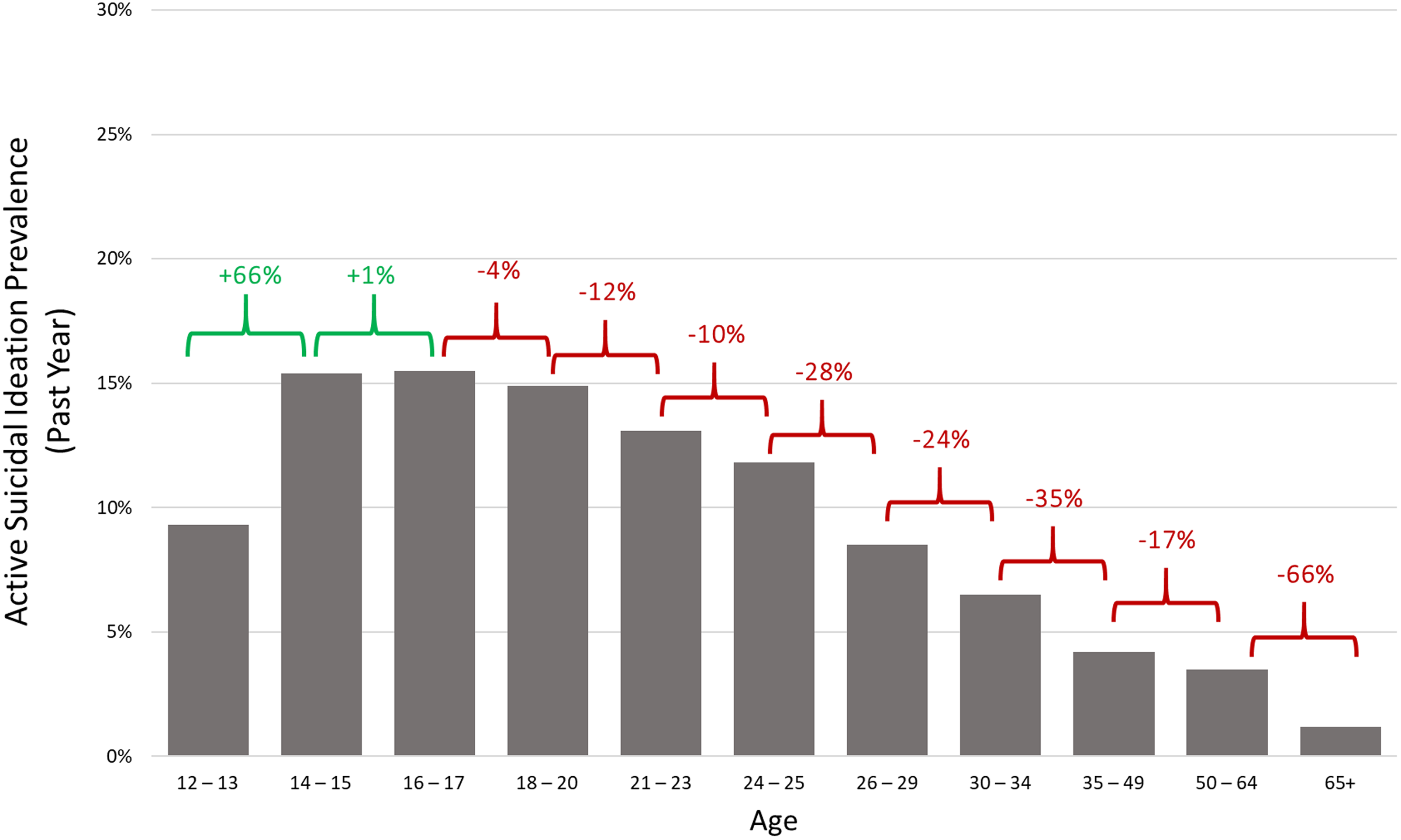

Most of what we know about the timing of thoughts about life and death in the life span comes from the suicidology literature on active suicidal ideation. The onset of active ideation is somewhat less common before the age of 10 (Ortin-Peralta et al., Reference Ortin-Peralta, Sheftall, Osborn and Miranda2023), with the greatest increases in active suicidal ideation incidence occurring between the ages 12 and 17 (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Franz, Guzmán, Glenn, C., Kleiman and Nock2018; Miller & Prinstein, Reference Miller and Prinstein2019). According to the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, adolescents aged 14–17 reported higher rates of active suicidal ideation as compared to all other age cohorts in 2022 (SAMHSA, 2024). Active suicidal ideation reaches its peak at ages 16–17 and rapidly declines after young adulthood, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Active suicidal ideation past year prevalence by age, 2022.

Furthermore, YRBSS data suggest that more than one in every five (∼22%) high-school aged adolescents reported serious consideration of suicide in the past year in 2021 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023b).

Active suicidal ideation is a strong predictor of suicide attempts in both adolescence and young adulthood (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Kingsbury, Warner, Landry, Clayborne, Islam and Colman2023; Castellví et al., Reference Castellví, Lucas-Romero, Miranda-Mendizábal, Parés-Badell, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Roca, Rodríguez-Marín, Rodríguez-Jimenez, Soto-Sanz and Alonso2017). Among adolescents who transition from ideation to attempt, the majority do so within one to two years of active suicidal ideation onset (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Green, Hwang, McLaughlin, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2013). Even among adolescents who never attempt suicide, active suicidal ideation can cause long-term impairment, suffering, and health care costs (Babcock et al., Reference Babcock, Moussa and Diaby2022; Jobes et al., Reference Jobes, Mandel, Kleiman, Bryan, Johnson and Joiner2024; Oppenheimer et al., Reference Oppenheimer, Glenn and Miller2022; Wastler et al., Reference Wastler, Khazem, Ammendola, Baker, Bauder, Tabares, Bryan, Szeto and Bryan2022a), warranting attention as a prevention target by itself.

Most suicide attempts after adolescence are reattempts in clinical populations, with the time intervals between reattempts decreasing with greater frequency of attempted suicide (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Franz, Guzmán, Glenn, C., Kleiman and Nock2018; Goldston et al., Reference Goldston, Daniel, Erkanli, Heilbron, Doyle, Weller, Sapyta, Mayfield and Faulkner2015). In a 2023 meta-analysis, young adults who reported active suicidal ideation and attempts during adolescence had more than twice and five times the odds of attempted suicide during young adulthood, respectively, than young adults without a history of suicidal thoughts and behaviors during adolescence (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Kingsbury, Warner, Landry, Clayborne, Islam and Colman2023). In addition, young adults who strongly considered suicide during adolescence had more than three times the odds of reporting active suicidal ideation in young adulthood, adjusting for concurrent mental health disorders, than young adults without a history of suicidal ideation during adolescence (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Kingsbury, Warner, Landry, Clayborne, Islam and Colman2023).

Adolescents who report high active suicidal ideation frequency – how often active suicidal ideation occurs in a given time frame; duration – how long active suicidal ideation occurs for; and persistence – the extent to which active suicidal ideation is transient; are among the most likely to transition to attempted suicide (Czyz et al., Reference Czyz, Koo, Al-Dajani, Kentopp, Jiang and King2022; Czyz & King, Reference Czyz and King2015; Erausquin et al., Reference Erausquin, McCoy, Bartlett and Park2019; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Rosario-Williams, Kelly, Macrynikola and Sullivan2022; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Scott and Shaffer2014). Adolescents with a history of attempted suicide – a relatively strong predictor of future suicide attempts (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Kingsbury, Warner, Landry, Clayborne, Islam and Colman2023; Castellví et al., Reference Castellví, Lucas-Romero, Miranda-Mendizábal, Parés-Badell, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Roca, Rodríguez-Marín, Rodríguez-Jimenez, Soto-Sanz and Alonso2017) – are more likely to report that their recent ideation lasted greater than four hours than adolescents with active suicidal ideation without a history of attempt (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Macrynikola, Nahum, Mañanà, Rombola, Runes and Wasee2023). Meanwhile, ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) – self-report assessments (e.g., on mobile devices) at multiple points throughout the day to collect psychological and behavioral data – have revealed notable variability in day-to-day active suicidal ideation among adolescents. Same-day, and not next day, concurrency of active SI thought frequency, duration, and severity is associated with greater risk (e.g., hopelessness) and reduced protective factors (e.g., connectedness) for suicidal behavior (Czyz et al., Reference Czyz, Horwitz, Arango and King2019). In addition, adolescents are at significantly higher odds to report suicidal rumination, or mental fixation on their suicidal thoughts, in the twenty-four hours prior to an attempt as compared to a 24-hour comparison period (King et al., Reference King, Allen, Ahamed, Webb, Casper, Brent, Grupp-Phelan, Rogers, Arango, Al-Dajani, McGuire and Bagge2023).

The content of active suicidal ideations may vary with a history of suicide attempts. In an analysis of two combined study samples of individuals aged 12–19, adolescents with a recent suicide attempt were more likely to think about the process of dying, what would happen to the body (41% vs 29%), and someone finding them after their attempt (40% vs 25%) than adolescents with active suicidal ideation without a history of attempted suicide (albeit not statistically significant; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Macrynikola, Nahum, Mañanà, Rombola, Runes and Wasee2023).

Adolescents with active suicidal ideation and a history of attempted suicide endorse greater suicide-related mental imagery in addition to verbal suicide-related cognitions than adolescents with active suicidal ideation without a history of attempted suicide (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Macrynikola, Nahum, Mañanà, Rombola, Runes and Wasee2023). In a recent study of psychiatric unit patients, adolescents who reported suicide-related mental imagery had more than twice the odds of having made a suicide attempt when controlling for verbal suicide-related cognitions, as compared to adolescents without suicide-related mental imagery (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Nesi, Burke, Liu, Spirito, Hunt and Wolff2021).

Active suicidal ideation is shaped by an enhanced sensitivity to social stimuli during adolescence (Crone & Fuligni, Reference Crone and Fuligni2020; Pfeifer et al., Reference Pfeifer, Masten, Borofsky, Dapretto, Fuligni and Lieberman2009). Extant research has identified a robust relationship between exposure, such as through the death of a peer or family member who has died due to suicide, and adolescent active suicidal ideation (Calderaro et al., Reference Calderaro, Baethge, Bermpohl, Gutwinski, Schouler-Ocak and Henssler2022; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Vivolo-Kantor, Logan and Leemis2017), termed as “social transmission” (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Hill, Gould, John, Lascelles and Robinson2020). In particular, the family is an interpersonal context for potential exposure and susceptibility (Brent & Melhem, Reference Brent and Melhem2008; Calderaro et al., Reference Calderaro, Baethge, Bermpohl, Gutwinski, Schouler-Ocak and Henssler2022; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Vivolo-Kantor, Logan and Leemis2017; Mann & Rizk, Reference Mann and Rizk2020; O’Reilly et al., Reference O’Reilly, Kuja-Halkola, Rickert, Class, Larsson, Lichtenstein and D’Onofrio2020; Oppenheimer et al., Reference Oppenheimer, Stone and Hankin2018), as well as a protective factor (Galindo-Dominguez & Iglesias, Reference Galindo-Domínguez and Iglesias2023; Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Quinn, Jones and Beer2021; Kasen & Chen, Reference Kasen and Chen2020; Lo et al., Reference Lo, Kwok, Yeung, Low and Tam2017; Machell et al., Reference Machell, Rallis and Esposito-Smythers2016; Ruiz-Robledillo et al., Reference Ruiz-Robledillo, Ferrer-Cascales, Albaladejo-Blázquez and Sánchez-SanSegundo2019) for adolescent active suicidal ideation. In addition, adolescents with friends who have active suicidal ideation are more likely to report seriously consideration of suicide (Schlagbaum et al., Reference Schlagbaum, Tissue, Sheftall, Ruch, Ackerman and Bridge2021), which is noteworthy given that adolescents endorse disclosing their active suicidal ideation to their close friends or significant others (Holland et al., Reference Holland, Vivolo-Kantor, Logan and Leemis2017). Lastly, the school environment, an interpersonal setting in which adolescents spend a majority of their time, is of particular importance for adolescent attempted suicide, with feelings of school belongingness, safety, norms, and teacher support each associated with reduced likelihood of active suicidal ideation and behavior during adolescence (Ancheta et al., Reference Ancheta, Bruzzese and Hughes2021, Benbenishty et al., Reference Benbenishty, Astor and Roziner2018; Kasen & Chen, Reference Kasen and Chen2020).

Passive suicidal ideation

Recent research in the suicidology literature isolated the latent structure of suicidal thought content in distinguishing passive and active ideation (Wastler et al., Reference Wastler, Khazem, Ammendola, Baker, Bauder, Tabares, Bryan, Szeto and Bryan2022a). In a study of US adults, thoughts that are typically characterized as passive ideation “I wish I could disappear or not exist,” “I wish I were never born,” “My life is not worth living” and “I wish I could go to sleep and never wake up again” strongly loaded onto one factor, while thoughts that included: “Maybe I should kill myself,” “I should kill myself,” and “I am going to kill myself” loaded onto a second factor representing active ideation (Wastler et al., Reference Wastler, Khazem, Ammendola, Baker, Bauder, Tabares, Bryan, Szeto and Bryan2022a). Of course, these factors might look slightly differently among adolescents (see below our discussion of single item vs. multiple item screening tools for adolescents).

This distinguishing between active and passive ideation was critical to articulating pathways from thoughts to behaviors (ideations to attempts) as well as determining which individuals were most at risk. Indeed, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care were amended in 2022 to include universal screening of suicide risk for adolescents aged 12 and up (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2023a). Of the publicly available evidence-based tools AAP recommends (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2023b), the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions toolkit specifies the need for a full mental health evaluation for individuals who indicate same day active suicidal ideation, but only a brief suicide safety assessment for those with active or passive suicidal ideation that occurred in the past few weeks (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], n.d.-a; n.d.-b). Meanwhile, one of the leading suicide screening tools: the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating scale (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova, Oquendo, Currier, Melvin, Greenhill, Shen and Mann2011) specifies immediate action for those with active suicidal ideation and intent with or without a specific plan, but not for those with only passive ideation; a distinction that would not have been possible without the foundational theoretical (and empirical) work on suicidal ideation. In each of these scales, passive suicidal ideation is endorsed with a single item. It is important to note, however, that passive suicidal ideation may present in nuanced and varying ways in a subsample of adolescents. In a study of adolescents, an estimated two thirds of adolescents with passive suicidal ideation go undetected when completing a single-item measure of suicidal ideation, as compared to a multi-item assessment (Gratch et al., Reference Gratch, Tezanos, Fernades, Bell and Pollak2022). However, such multi-item assessments are infrequently used, often due to the participant burden.

Unlike the literature on active suicidal ideation, the onset and prevalence of passive suicidal ideation among adolescents remains relatively understudied in national data sets and empirical studies, with the authors of a 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis deciding to exclude passive suicidal ideation as an outcome due to a low number of reported effect sizes in the existing literature among youth (Van Meter et al., Reference Van Meter, Knowles and Mintz2023). Existing evidence does suggest that passive suicidal ideation has its greatest increase and first onset during adolescence, mirroring active ideation (Liu et al, Reference Liu, Bettis and Burke2020). However, passive suicidal ideation may be as or marginally more prevalent than active suicidal ideation during adolescence. Based on a baseline sample collected from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, more than one in every twenty 9–10-year-olds (6.4%) reported a lifetime history of passive suicidal ideation, as compared to 4.4% reporting lifetime active suicidal ideation (DeVille et al., Reference DeVille, Whalen, Breslin, Morris, Khalsa, Paulus and Barch2020). Similarly, in a study of adolescents aged 11–19 screened in an emergency department, approximately 13.5% of patients reported past month passive suicidal ideation, as compared to 11.3% endorsing past month active suicidal ideation (Rufino et al., Reference Rufino, Kerr, Beyene, Hill, Saxena, Kurian, Saxena and Williams2022). In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, age was inversely associated with passive ideation prevalence – with adolescents being the most likely of any age cohort to report ever feeling a desire to no longer be alive (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Bettis and Burke2020).

Passive to active ideation: sequential, separate, or synergistic?

In the frameworks that include active and passive suicidal ideation as distinct constructs, the three-step and interpersonal theories of suicide consider the sequence of more than one ideation (Joiner et al., Reference Joiner, Van Orden, Witte and Rudd2009; Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010).

Both the three-step and interpersonal theories conceptualize passive ideation as a sequential, nonconcurrent step preceding the transition from active ideation to attempted suicide. In describing an individual who has daily experiences of pain (e.g., psychological, physical) and hopelessness, Klonsky & May state that if a person’s connectedness is greater than their pain, an “individual may still have passive ideation, but will not progress to active desire for suicide. However, if both pain and hopelessness are present, and connectedness is absent or less than the pain, the individual will have strong suicidal ideation and an active desire to end his or her life” (2015). Similarly, Van Orden et al., present a hypothesis for active suicidal ideation that can only be met if an individual is experiencing passive suicidal ideation in the presence of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and hopelessness (2010). The authors also hypothesize that suicide attempts only occur “in the context of suicidal intent (which results from thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and hopelessness regarding both), reduced fear of suicide, and elevated physical pain tolerance (2010).” In other words, passive ideation is conceptualized as occurring first chronologically and directly preceding the transition from active suicidal ideation to attempted suicide termed as a sequential, hierarchical continuum of risk (Wastler et al., Reference Wastler, Bryan and Bryan2022b). A similar conceptualization is used in current empirical analyses of suicidal ideation, with severity implicitly conceptualized as ranging from passive suicidal ideation, to nonspecific active suicidal ideation (i.e., active suicidal ideation without intention), to active suicidal ideation with intent (Ortin-Peralta et al., Reference Ortin-Peralta, Sheftall, Osborn and Miranda2023).

While there is substantial evidence to support the sequential, hierarchical continuum of risk in adults (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Bettis and Burke2020; Wolford-Clevenger et al., Reference Wolford-Clevenger, Stuart, Elledge, McNulty and Spirito2020), not all studies with adolescents do (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Macrynikola, Nahum, Mañanà, Rombola, Runes and Wasee2023; Romanelli et al., Reference Romanelli, Sheftall, Irsheid, Lindsey and Grogan2022). In fact, there is emerging evidence in Black adolescent samples that there are at least a small group of individuals whose attempt behavior is not preceded by ideation at all (Romanelli et al., Reference Romanelli, Sheftall, Irsheid, Lindsey and Grogan2022).

Moreover, there is emerging evidence that the co-occurrence of passive and active ideation might have synergistic effects (Reference Wastler, Bryan and Bryan2022b; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Macrynikola, Nahum, Mañanà, Rombola, Runes and Wasee2023, Wastler et al., Reference Wastler, Khazem, Ammendola, Baker, Bauder, Tabares, Bryan, Szeto and Bryan2022a): what we term as the concurrent suicidal cognition assumption. In a recent study, adolescents who had a history of a prior suicide attempt had a high duration (>4 hours) of active suicidal ideation and greater odds of passive suicidal ideation (“a wish to die”) than adolescents without a history of suicide attempt (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Macrynikola, Nahum, Mañanà, Rombola, Runes and Wasee2023). The concurrence of suicidal ideations is particularly likely among adolescents (as compared with adults), given that adolescence is a period of the highest onset and prevalence of active and passive ideation (SAMHSA, 2024; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Bettis and Burke2020; Nock et al., Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Alonso, Angermeyer, Beautrais, Bruffaerts, Chiu, de Girolamo, Gluzman, de Graaf, Gureje, Haro, Huang, Karam, Kessler, Lepine, Levinson, Medina-Mora, Ono, Posada-Villa and Williams2008).

The cognitive theory of suicide (Wenzel & Beck, Reference Wenzel and Beck2008) incorporates insights into how characteristics of suicidal ideations matter in the transition to attempted suicide. The authors hypothesize that the transition from cognitive processes associated with suicidal acts and suicidal behavior occurs when individuals cross a “threshold of tolerance:” when their cognitions are no longer bearable. Cognitive processes associated with suicidal acts include “maladaptive cognitive contents” (e.g., the ideations an individual has about ending their own life) and “information processing biases” (e.g., attentional fixation on suicide-related cues). According to the theory, certain “dispositional vulnerability factors” – the repetitive/ruminative quality of their negative cognitions i.e., in their frequency, intensity, and/or duration– may affect the ways in which individuals perceive the “unbearability” and “hopelessness” of their cognitive states (Holdaway et al., Reference Holdaway, Luebbe and Becker2018; Horwitz et al., Reference Horwitz, Czyz and King2015; Wenzel & Beck, Reference Wenzel and Beck2008; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Miranda and Nolen-Hoeksema2007).

In the subsequent sections, we outline adolescence as a distinct developmental period for the concurrence of cognitions, not only for suicidal ideations (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Rosario-Williams, Kelly, Macrynikola and Sullivan2022), but also for other, non-suicidal thoughts adolescents have about death and life. We then consider how these non-suicidal cognitions about life and death may play a role in suicide attempts, alongside and in their concurrence with suicidal ideations. In doing so, our goal is to build a theory of adolescent suicide prevention that considers these cognitions in a single unified framework, for which we invite empirical study. We note that when prior research has considered thoughts about life and death, they are conceptualized and measured as risk or protective factors, as being present or not present, with no clear understanding in how the content, timing, and mental imagery of life, mortality, and suicidal cognitions together shape suicide trajectories. We hypothesize that adolescence is a time in which efforts to reduce thoughts concerning suicide (i.e., active and passive suicidal ideation) while addressing non-suicidal mortality and life cognitions may be particularly efficacious in preventing the transition from ideation to attempt.

Non-suicidal mortality cognitions during adolescence

Adolescent existential anxieties about death

While adolescents develop a mature conceptualization of mortality in early adolescence, it is not until late adolescence that death becomes a primary source of existential anxiety: hypothesized as a normative phenomenon (Berman et al., Reference Berman, Weems and Stickle2006; Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Hutchinson, Manias and Bouchoucha2022). Existential anxieties of death during adolescence include the fears or worries about an adolescent’s own mortality, the death of their friends or family, dying, and/or of the unknown (Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Hutchinson, Manias and Bouchoucha2022). There are mixed findings on whether existential anxieties about death are positively or negatively associated with considerations of suicide during adolescence. Some evidence suggests that fearlessness of death, a characteristic of existential anxiety, is associated with attempted suicide among adolescents (Ferm et al., Reference Ferm, Frazee, Kennard, King, Emslie and Stewart2020). Meanwhile, adolescents with active suicidal ideation report greater levels of anxiety and apprehension about death (for a review, see Sims et al., Reference Sims, Menzies and Menzies2024).

Adolescent defenses to death

Adolescents navigate the salience and related existential anxieties of death in their day-to-day lives by avoiding cognitions related to mortality and instead focus on their sense of self and their cultural and societal views The Terror Management Theory posits that when adolescents have normative, yet oftentimes debilitating, anxieties about death, they deploy defense mechanisms to reduce the awareness of the impending threat to the mortality of their self and others (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Pyszczynski, Solomon and Baumeister1986; Pyszczynski et al., Reference Pyszczynski, Solomon and Greenberg2015).

There are two types of defense mechanisms deployed when mortality is salient, or when an adolescent is exposed to (a) the idea of death, (b) the actual or near death of a loved one, or (c) to death-related anxieties. Mortality salience during adolescence immediately results in adolescents consciously suppressing or denying their access to death-related thoughts (Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Hutchinson, Manias and Bouchoucha2022). Preliminary research has indicated that adolescents with a history of active suicidal ideation have less death cognition avoidance as compared to adolescents without a history of active suicidal ideation (Tezanos et al., Reference Tezanos, Pollak and Cha2021). Over time, exposure to death is hypothesized to prime adolescents to use distal/symbolic defenses. These distal defenses include an adolescent’s worldview (i.e., their view on reality that imbues life with meaning, purpose, and transcendence from death) and their self-esteem (i.e., how well one is living up to their worldview; Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Hutchinson, Manias and Bouchoucha2022). It is hypothesized that adolescents with weakened distal defenses are unable to reduce the salience of mortality in their day-to-day lives (Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Hutchinson, Manias and Bouchoucha2022).

Adolescent death acceptance

Death acceptance is an adolescent’s cognitive awareness of their own mortality and their affective response to this cognition comprising of three components, including neutral acceptance, approach acceptance, and escape acceptance (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Reker and Gesser1994). Neutral acceptance is the view of death as an unchangeable element of life. Death is thought to highlight the finite nature of existing and allows individuals with neutral acceptance to primarily focus on having a life worth living (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Reker and Gesser1994). Approach acceptance is the belief that death will result in a happy afterlife (1994), and is associated with religiosity (Dezutter et al., Reference Dezutter, Luyckx and Hutsebaut2009). Lastly, escape acceptance is the view of death as a welcome alternative to the pain (e.g., psychological, physical) and suffering experienced in life (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Reker and Gesser1994). Endorsement of escape acceptance is associated with greater likelihood of future adolescent active suicidal ideation recurrence and severity (Tezanos et al., Reference Tezanos, Pollak and Cha2021). Furthermore, adolescents with a history of attempted suicide report death as a solution to unsolvable challenges in life as a driver of their suicidal behavior (May et al., Reference May, O’Brien, Liu and Klonsky2016). Important to note is that greater exposure to death, particularly of a parent or loved one, is associated with a stronger attraction to death and lower levels of attraction to life as compared with adolescents without this exposure (Andriessen et al., Reference Andriessen, Draper, Dudley and Mitchell2016; Gutierrez et al., Reference Gutierrez, King and Ghaziuddin1996)

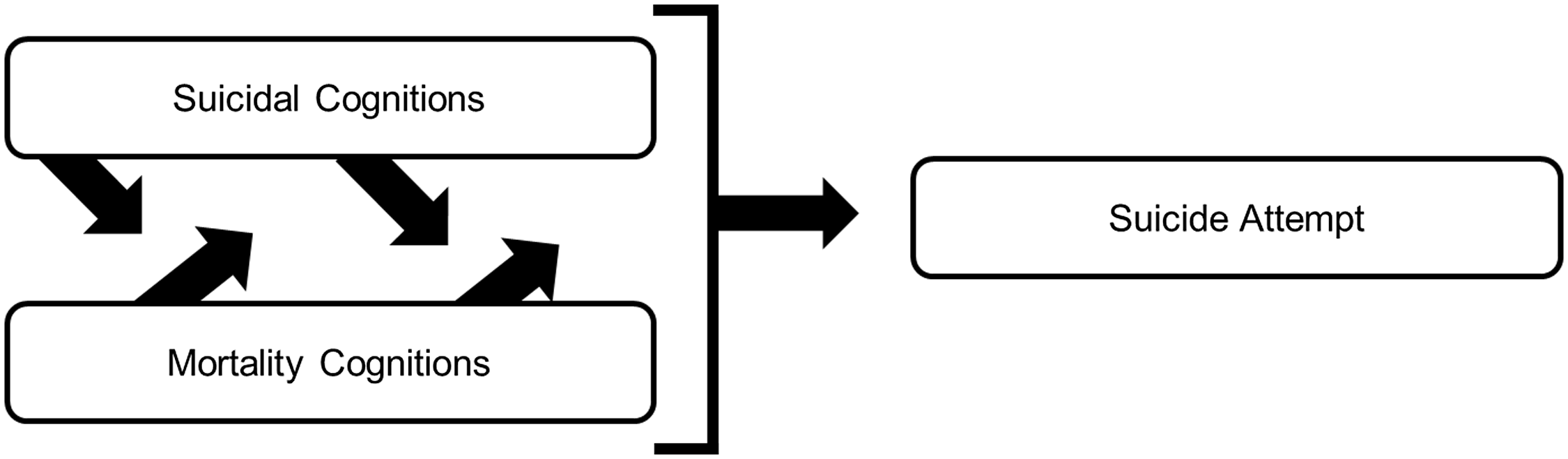

We posit that these non-suicidal cognitions about death (or mortality cognitions) may co-occur alongside suicidal cognitions and together with suicide cognitions, contribute to suicide attempts. We show these hypothesized relations in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Suicidal and non-suicidal mortality cognition concurrence during adolescence.

Mortality cognition onset and prevalence

An emerging body of evidence suggests that non-suicidal cognitions about mortality begin to form and are highly prevalent and developmentally typical (for a discussion, see: Oppenheimer et al., Reference Oppenheimer, Glenn and Miller2022) during adolescence and may co-occur with the onset of suicidal ideations described above. Children explore the concept of death through conversations with their parents as early as three years of age (Renaud et al., Reference Renaud, Engarhos, Schleifer and Talwar2015) and gain more sophisticated conceptualizations of their own mortality in their incorporation of scientific knowledge and belief systems by late childhood (Legare et al., Reference Legare, Evans, Rosengren and Harris2012). Research indicates that by the age of 11, adolescents develop a conceptualization of death as inevitable and universal (Berman et al., Reference Berman, Weems and Stickle2006; Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Hutchinson, Manias and Bouchoucha2022). Importantly, children 3–6 years of age with a history of depression and suicidal ideation frequently have a mature understanding of death (i.e., its universality, irreversibility, applicability, cessation, causality) that is more developmentally similar to adolescents than to their same aged counterparts (Hennefield et al., Reference Hennefield, Whalen, Wood, Chavarria and Luby2019).

Adolescent implicit associations with death

From childhood to adolescence, individuals form abstract, mental representations and related biases for: same-race, religion, gender, and, in this instance: death. Implicit associations for death are the extent to which adolescents classify constructs of death, such as dead, deceased, lifeless, die, and suicide with attributes/indicators of who they are: me, I, myself, mine, and self (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Park, Finn, Deliberto, Dour and Banaji2010). The death implicit association test (d-IAT), for example, relies upon reaction times in classifying self and other with constructs of death, with greater implicit bias being associated with shorter latencies in response (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Millner, Esposito, Porter and Nock2019). In a systematic review and meta-analysis, findings indicated that higher d-IAT scores were associated with greater odds of attempted suicide, and was able to discriminate between individuals with and without a history of a suicide attempt (Sohn et al., Reference Sohn, McMorris, Bray and McGirr2021). Among adolescent outpatient samples, d-IAT scores is predictive of the occurrence, but not the frequency, of active suicidal ideation over the course of: three months (Brent et al., Reference Brent, Grupp-Phelan, O’Shea, Patel, Mahabee-Gittens, Rogers, Duffy, Shenoi, Chernick, Caspter, Webb, Nock and King2023) and a year (albeit not significantly when controlling for prior suicidal ideation; Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Millner, Esposito, Porter and Nock2019). In addition, higher d-IAT scores were higher amongst adolescents with a history of a suicide attempt who reattempted during the period prior to the one-year follow-up assessment (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Millner, Esposito, Porter and Nock2019).

Thoughts about life during adolescence

Below, we outline five domains of life cognitions that may warrant additional attention in the field of adolescent suicidology: hope, curiosity, emotional intelligence, social cognition, and meaning making.

Hope

Although hope/hopelessness have been included in ideation-to-action frameworks (see three-step theory & interpersonal theories of suicide), it has not been conceptualized as a separate co-occurring cognition (Joiner et al., Reference Joiner, Van Orden, Witte and Rudd2009; Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010). For the purposes of our review, we define hope as a bidimensional phenomenon that comprises goal-oriented cognitive processes: agency and pathway thinking. When seeking to achieve a goal, agency thinking is the motivation and perceived ability that an adolescent has in reaching a goal in their day-to-day lives and the near-to-distant future (Snyder, Reference Snyder1994; Reference Snyder2000). Meanwhile pathways thinking are the ways in which an adolescent considers their capacity to identify the key steps needed to achieve the desired goal (Snyder, Reference Snyder1994; Reference Snyder2000).

Positive future thinking – or the ability/capacity to imagine desirable events that may occur in one’s life – is one element of agency and pathways thinking that has received attention as a heterogenous construct: that is not uniformly harmful or beneficial in the prediction of suicide outcomes (Nam & Cha, Reference Nam and Cha2023). In the extant literature, lack of positive future thinking has been associated with hopelessness and a predictor of active suicidal ideation (Nam & Cha, Reference Nam and Cha2023). Recent empirical work has sought to understand how the content of positive future thinking is associated with active suicidal ideation. For example, novelty in positive future thinking, the degree to which one’s view of their future is starkly different from their past or present, was associated with severity in active suicidal ideation at baseline in an analysis of adolescents aged 12–17 completing a future thinking task (Nam & Cha, Reference Nam and Cha2023). Interestingly, when a positive event occurred within the time between the baseline and the 6-month follow-up, adolescents who imagined an event as more novel at baseline experienced them less positively than imagined at the 6-month follow-up, which was significantly associated with severity of active suicidal ideation at the follow-up (Nam & Cha, Reference Nam and Cha2023). An analysis of a community-based sample of adolescents reported a similar result, in which the relationship between defeat and active suicidal ideation was strongest when positive future thinking was unrealistic and unachievable (Pollak et al., Reference Pollak, Guzmán, Shin and Cha2021). This work aligns with the literature on personal narratives – the ways in which adolescents make sense of the coherence of their self in the past, present, and in an imagined future, where reduced identity coherence across time is associated with negative mental health outcomes (Adler, Reference Adler2012).

Lastly, some preliminary work has examined the timing of positive future thinking and active suicidal ideation. In an analysis looking at the concurrence of active suicidal ideation and short-term future thinking in a community sample of adolescent twins, more frequent active suicidal ideation in the past week was associated with less daily positive future thinking (Kirtley et al., Reference Kirtley, Lafit, Vaessen, Decoster, Derom, Gülöksüz, De Hert, Jacobs, Menne-Lothmann, Rutten, Thiery, van Os, van Winkel, Wichers and Myin-Germeys2022).

Adolescence is a sensitive period of brain development for hope and related positive future thinking, particularly in regions that are involved in higher-level cognitive processes including planning, goal-directed behaviors, and self-referential thinking (Li et al., Reference Li, Lindenmuth, Tarnai, Lee, King-Casas, Kim-Spoon and Deater-Deckard2022, Ordaz et al., Reference Ordaz, Goyer, Ho, Singh and Gotlib2018). In particular, adolescents develop the capacity to voluntarily suppress ideations that are not in alignment with a goal-driven response (Luna, Reference Luna2009). The ability to see the self as having the motivation and skill needed to achieve a goal in the near-to-distant future is in direct opposition to the want or serious consideration to no longer be alive (Grewal & Porter, Reference Grewal and Porter2007).

Given the capacity to plan, as well as to have a perception of self that can achieve a desired goal is in development during adolescence (Li et al., Reference Li, Lindenmuth, Tarnai, Lee, King-Casas, Kim-Spoon and Deater-Deckard2022), some adolescents may have particular difficulty with imagining a realistic future in which they achieve their aspirations when experiencing adversity. When facing consistent, and seemingly endless challenges, it is hypothesized that adolescents may have less active or frequent cognitions about their life goals (Grewal & Porter, Reference Grewal and Porter2007). Furthermore, the abandonment of existing life goals in tandem with the emergence of agency and pathway thinking to achieve a new goal of suicide, may escalate suicidal ideation to attempt during adolescence (2007). In short, we posit it that co-occurring hope that is tied to suicide-related goals, in tandem with suicidal ideations may result in suicide attempts, while positive, healthy hope cognitions alongside suicide ideations may mitigate the transition from ideation to behavior.

Curiosity

While overwhelmingly characterized as a time of risk-taking, impulsivity, and sensation seeking (Crone & van Duijvenvoorde, Reference Crone and van Duijvenvoorde2021; Willoughby et al., Reference Willoughby, Heffer, Good and Magnacca2021), there has been increasing attention on the heightened experience of curiosity during adolescence, not as an innate drive, emotion, or fixed trait, but rather as a fluctuating cognitive state (Gruber & Fandakova, Reference Gruber and Fandakova2021; Marvin et al., Reference Marvin, Tedeschi and Shohamy2020). Indeed, recent developmental cognitive neuroscience posits a triadic system with an approach/reward system (ventral striatum) and an avoidance/emotional system (amygdala), alongside a weaker prefrontal cortex control system (Ernst, Reference Ernst2014; Telzer et al., Reference Telzer, Van Hoorn, Rogers and Do2018; Telzer, Reference Telzer2016). In particular, we define curiosity as the cognitions adolescents have in the exploration of new experiences and information (stretching) and in their comfort with the novelty and unpredictability of life (embracing; Kashdan & Steger, Reference Kashdan and Steger2007; Marvin et al., Reference Marvin, Tedeschi and Shohamy2020). Preliminary evidence has indicated that curiosity is associated with reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms over time (Zainal & Newman, Reference Zainal and Newman2022) and buffers the impact of stress on suicidal ideation intensity in nonadolescent samples (Denneson et al., Reference Denneson, Smolenski, Bush and Dobscha2017), and, more broadly shapes positive affect, risk-taking behavior, and motivation among adolescents (Gruber & Fandakova, Reference Gruber and Fandakova2021; Jovanović & Gavrilov-Jerković, Reference Jovanović and Gavrilov-Jerković2014).

Conceptualizations of curiosity are continuing to evolve. Most recently, Metcalfe and Jacobs conceptualize curiosity as two separate phenomena, each residing within distinct neural systems, termed Curiosity1 and Curiosity2 (in press; Metcalfe et al., Reference Metcalfe, Vuorre, Towner and Eich2022). Curiosity1 is goal-oriented exploration that is characterized by reward-seeking, habit formation, and reinforcement-based learning (Metcalfe & Jacobs, Reference Metcalfe and Jacobs2023; Metcalfe et al., Reference Metcalfe, Vuorre, Towner and Eich2022). Studies have shown that discrepancies between expectation and reality (i.e., prediction errors) in response-based learning tasks enhances memory in adolescents aged 10 to 14, more so than for children, indicating increased utilization of prefrontal cortex appraisal and reward-seeking/dopaminergic modulation of regions of the brain involved in memory formation during adolescence (Fandakova & Gruber, Reference Fandakova and Gruber2021; Gruber & Fandakova, Reference Gruber and Fandakova2021). Of note are studies suggesting that reward-seeking amongst depressed or suicidal adolescents is impaired as compared to nondepressed and non-suicidal adolescents (Gifuni et al., Reference Gifuni, Perret, Lacourse, Geoffroy, Mbekou, Jollant and Renaud2020).

Meanwhile, Curiosity2 is the exploration of novel information and experiences that is non-goal or reward-oriented and which result in the formation and consolidation of life experiences, otherwise known as episodic memory (Metcalfe et al., Reference Metcalfe, Vuorre, Towner and Eich2022; Metcalfe et al., Reference Metcalfe, Vuorre, Towner and Eich2022). Episodic memory formation is under development during adolescence (for a review see: Ghetti & Fandakova, Reference Ghetti and Fandakova2020), and notably, adolescents with suicidal ideation have lower performance in episodic memory tasks than adolescents without suicidal ideation (Huber et al., Reference Huber, Sheth, Renshaw, Yurgelun-Todd and McGlade2022; Ortuño-Sierra et al., Reference Ortuño-Sierra, Aritio-Solana, Del Casal and Fonseca-Pedrero2021). Furthermore, Curiosity2, as well as other cognitions that may shape episodic memory formation during adolescence and which have yet to be identified, warrants attention in the prevention of adolescent suicidal ideation and behavior.

Emotional intelligence & appraisal/reappraisal

One way in which adolescents view their lives is through their experience and interpretation of emotions. Adolescents undergo greater affective fluctuations, are more sensitive to emotional experiences and report a higher magnitude/intensity in their emotional response than their adult and child counterparts (Schweizer et al., Reference Schweizer, Gotlib and Blakemore2020). In particular, adolescents experience greater frequency in high-intensity positive (involves a feeling or sense of pleasure; e.g., joy) and negative (involves a feeling or sense of displeasure; e.g., sadness) emotions and lower frequency in low intensity positive and negative emotions than do their adult counterparts. Similarly, older adolescents report more high-intensity negative emotions and relatively lower-intensity positive emotions than their younger adolescent counterparts (Bailen et al., Reference Bailen, Green and Thompson2019). Notably, negative affect, such as feelings of worthlessness and low self-esteem, is associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adolescents, while anhedonia, or a lack of positive affect, is at higher levels for adolescents with a history of suicide attempts as compared to their same age counterparts (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Franz, Guzmán, Glenn, C., Kleiman and Nock2018). Much of the existing suicide literature has sought to understand the relationship between the inability to regulate emotions (i.e., emotional dysregulation) and mental health (Beauchaine, & Hinshaw, Reference Beauchaine and Hinshaw2020; Hatkevich et al., Reference Hatkevich, Penner and Sharp2019a), as well as the relationship between emotional dysregulation and suicide during adolescence (for a review see: De Berardis et al., Reference De Berardis, Fornaro, Orsolini, Ventriglio, Vellante and Di Giannantonio2020). Meanwhile, emotional intelligence/appraisal has become an increasingly important cognitive process by which adolescents interpret their emotional landscape that warrants attention.

Emotional intelligence is defined in this manuscript as the cognitive processes by which adolescents perceive and regulate their affective states that is under development during adolescence (Young et al., Reference Young, Sandman and Craske2019) and is a protective factor for both adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts (Quintana-Orts, et al., Reference Quintana Orts, Rey Peña and Neto2021; Cha & Nock, Reference Cha and Nock2009; Domínguez-García & Fernández-Berrocal, Reference Domínguez-García and Fernández-Berrocal2018; Quintana-Orts et al., Reference Quintana-Orts, Mérida-López, Rey, Neto and Extremera2020). Adolescence is when individuals grow their emotional intelligence by learning how to suppress or alter their emotions over time (Schweizer et al., Reference Schweizer, Gotlib and Blakemore2020). Cognitive reappraisal is one way in which adolescents consciously reinterpret an emotionally salient stimuli to alter its intensity and valence (Schweizer et al., Reference Schweizer, Gotlib and Blakemore2020). For instance, if an adolescent feels particularly hopeless about their life after high school, they may rely on cognitive appraisal strategies to consider that: (1) they are still young and have time to think about the type of person they would like to be as an adult, (2) they can pull on their network of teachers and friends that have already helped them to reach their goals so far, and (3) what they are feeling might actually be positive, in that it means that they care about their future well-being and happiness. The use of cognitive appraisal strategies is associated with reduced likelihood of suicidal ideation (Franz et al., Reference Franz, Kleiman and Nock2021).

Social cognition

Social cognitions are the cognitive processes through which adolescents interpret the world in their interactions with others, that include perceptual processes such as face processing from an early age, and other more complex social cognitions including mentalizing that primarily develop across adolescence and into adulthood (Kilford et al., Reference Kilford, Garrett and Blakemore2016). Mentalizing allows adolescents to understand and predict the thoughts and emotions of others, cognitive theory of mind and affective theory of mind respectively, and to adjust their own cognitions, affect, and behaviors accordingly (Kilford et al., Reference Kilford, Garrett and Blakemore2016; Nestor & Sutherland, Reference Nestor and Sutherland2022). Impairments in cognitive and affective theory of mind tasks are associated with suicidal ideation and behavior (Nestor & Sutherland, Reference Nestor and Sutherland2022; Hatkevich et al., Reference Hatkevich, Venta and Sharp2019b). In particular, preliminary evidence suggest that adolescents who overly attribute personal meaning to the mental and emotional states of others have greater odds of suicidal ideation in the past month and attempted suicide in the past year than their counterparts without theory of mind impairments (Hatkevich et al., Reference Hatkevich, Venta and Sharp2019b).

Meaning making

Meaning in life encompasses two distinct processes regarding how an adolescent ascribes significance to their existence: the presence of meaning and the search for meaning. Meaning is present if an adolescent perceives their life to have a purpose and value to others, whereas the search for meaning is how adolescents learn to inquire about and establish meaning in their life (Dezutter et al., Reference Dezutter, Waterman, Schwartz, Luyckx, Beyers, Meca, Kim, Whitbourne, Zamboanga, Lee, Hardy, Forthun, Ritchie, Weisskirch, Brown and Caraway2014, Reference Dezutter, Luyckx and Hutsebaut2009; Steger et al., Reference Steger, Frazier, Oishi and Kaler2006). The search for and presence of meaning in life has frequently been utilized as a protective factor in analyses of adolescent suicide (Costanza et al., Reference Costanza, Prelati and Pompili2019), with limited consideration as a cognition. Little is known about how the content of the cognitions of meaning making (i.e., I have a meaningful life, messages from my friends make me excited to wake up in the morning), their timing, such as their concurrence in relation to when suicidal or non-suicidal mortality cognitions occur, and the richness and vividness of their verbal thoughts and/or mental imagery predicts attempted suicide during adolescence, and across the lifespan.

Meaning in life during adolescence is conceptualized and measured in the existing adolescent suicidology literature as a fixed state: of having or not having, searching for or not searching for “meaning in life.” However, adolescents have multiple dimensions in their lives in which they derive meaning. For example, in reconceptualizing resilience, Wexler et al., describe a dynamic process by which marginalized youth within a political and cultural context make personal and collective meaning of oppression and develop a shared purpose and values (Wexler et al., Reference Wexler, DiFluvio and Burke2009). Similarly, Urata proposes a model of personal, relational, social, and religious/spiritual meaning that is formed across a spectrum that includes pre-meaning: the state of being unconscious to perceptions of meaning; meaning in life: having a purpose and daily thoughts that life is fulfilling; supra-meaning: existential beliefs that surpass cognitions; trans-meaning: transcending the dichotomy of meaning and no-meaning; and no-meaning: emptiness in life (Urata, Reference Urata2015). Each example described above illustrates novel directions in understanding the ways in which meaning making occurs during adolescence and its relationship to suicidal ideation.

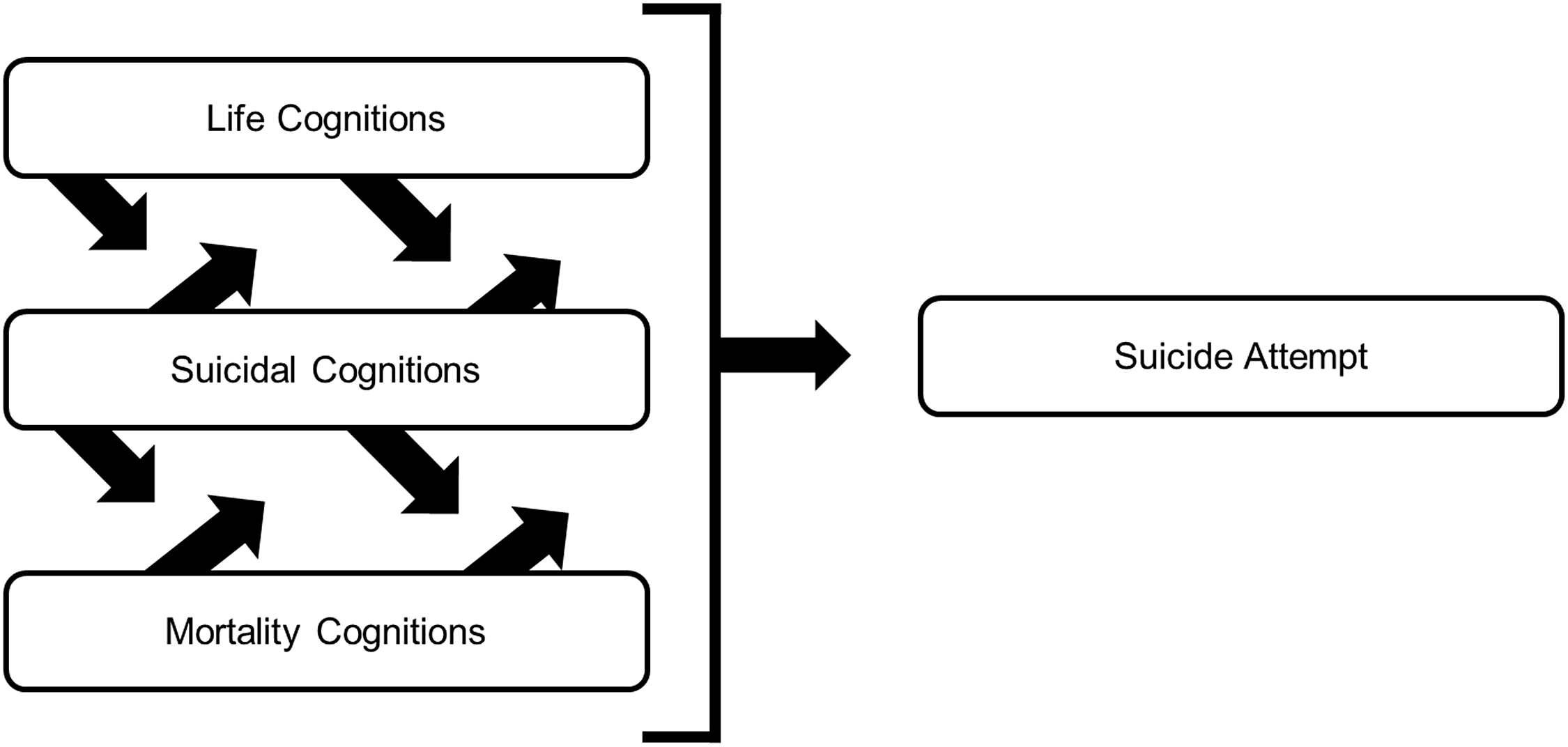

These five cognitions about life (life ideations) may be associated with reductions in suicidal ideations and non-suicidal mortality cognitions and contribute independently to suicidal behavior, as we show in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Suicidal, non-suicidal mortality, and life cognition concurrence during adolescence.

Life cognition onset and prevalence

As with non-suicidal mortality cognitions, adolescents begin to form thoughts about their life during adolescence that may co-occur with suicidal ideations. Some of these (e.g., meaning) have been considered in discussions of suicide prevention, even if they are often not directly considered in conceptualizations and empirical study of suicide attempts. While adolescents begin to have existential anxieties in early adolescence, it is not until late adolescence that living a life with meaning becomes a primary source of anxiety (Berman et al., Reference Berman, Weems and Stickle2006; Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Hutchinson, Manias and Bouchoucha2022). In particular, adolescence is a critical period in the development of life goals and values as well as in the establishment of a sense of direction and purpose in life (Kashdan & Steger, Reference Kashdan and Steger2007; Berman et al., Reference Berman, Weems and Stickle2006).

The cognition-to-action framework: a cognitive developmental theory of adolescent suicide

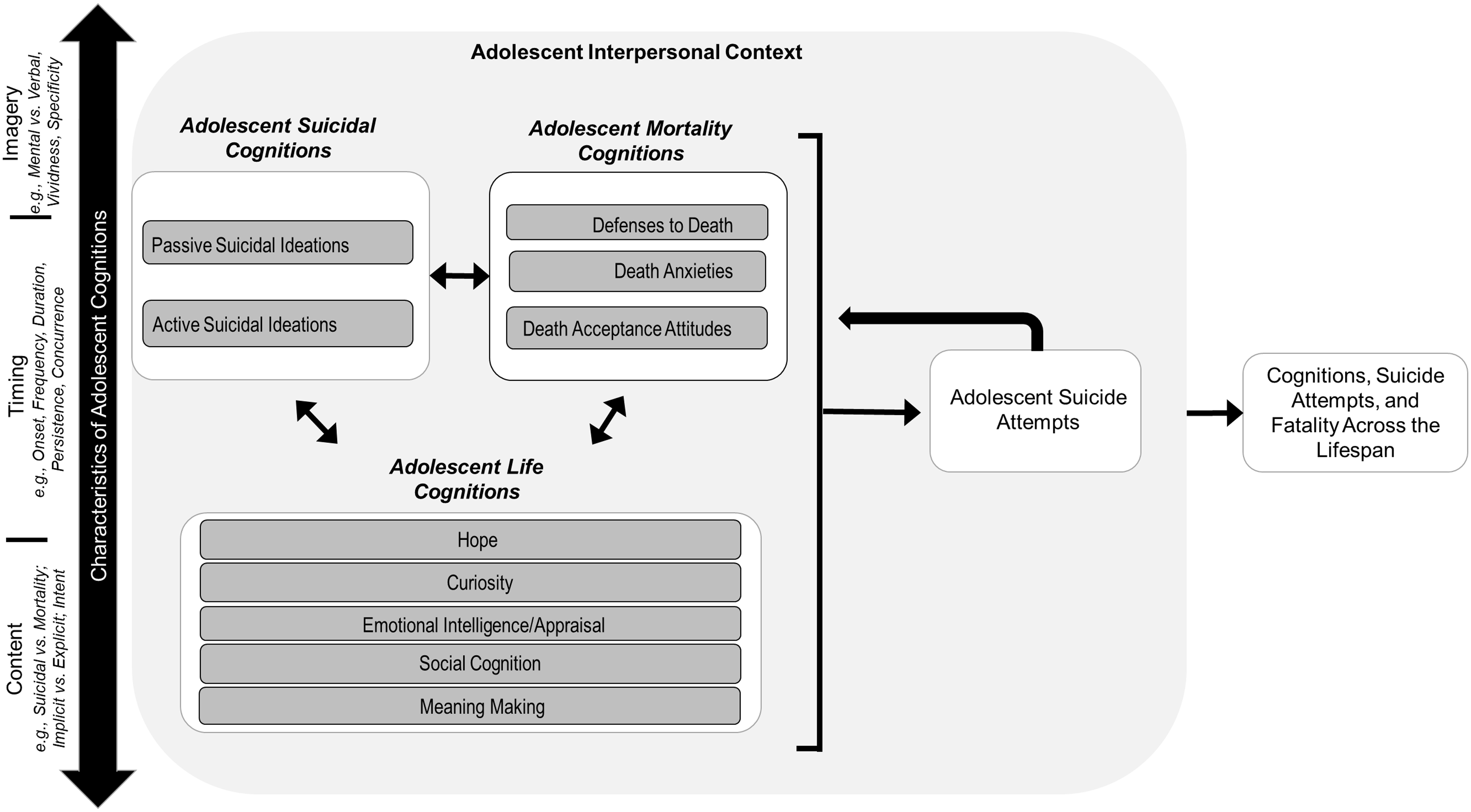

Below, we present the cognition-to-action framework, a cognitive developmental theory of adolescent suicide. The framework, depicted in Figure 4, synthesizes the extant science of cognitions from a review of the developmental science of how adolescents consider suicide, life, and mortality. It is designed as a roadmap for suicide researchers to conceptualize and operationalize the cognitions that have their onset during adolescence and the processes by which cognition shapes attempted suicide and fatality.

Figure 4. The cognition-to-action framework for adolescent suicide prevention.

We view our cognition-to-action framework as a variable-oriented theory – one that introduces, clarifies, and explicates constructs, with presumed relationships that operate between the constructs (Jaccard & Jacoby, Reference Jaccard and Jacoby2019). Variable-oriented theorizing was utilized in order to initiate the broader conceptualization of cognitions adolescents have relevant to attempted suicide beyond suicidal ideation. In particular, the cognition-to-action framework builds off of existing ideation-to-action frameworks to incorporate understandings from the fields of cognitive and developmental psychology to broaden the conceptualization of ideation during adolescence as thoughts about suicide, death, and life that warrant attention in research and programmatic efforts. To that end, our framework seeks to synthesize findings about cognition during adolescence, outline specific dimensions of cognitions, and consider how adolescent cognitions may have long-term implications for suicidal behavior and fatality across the lifespan. More specifically, our framework outlines cognitions that adolescents have about suicide, death, and life termed as adolescent suicidal, mortality, and life cognitions .

Adolescent suicidal cognitions , include active and passive ideation. Meanwhile, adolescent non-suicidal thoughts about death are termed in our model as mortality cognitions . Defenses to death, death anxieties, and acceptance attitudes represent thoughts adolescents have about death that are distinct from suicidal ideations and that are hypothesized to influence and be influenced by adolescent suicidal and life cognitions. Adolescents have thoughts about living and their existence, termed here as adolescent life cognitions, which include hope, curiosity, emotional intelligence/appraisal, social cognition, and meaning making, that are hypothesized to influence and be influenced by adolescent mortality and suicidal cognitions.

The framework also accommodates three types of cognition characteristics: content, timing, and mental imagery. Cognition content includes the types of cognition described above (e.g., suicidal, life, mortality), the nature of the content as implicit or explicit to the adolescent, and the intent of the adolescent to act on their cognition(s); cognition timing includes the onset, frequency, duration, persistence, and concurrence of their cognitions; and cognition imagery are the verbal and non-verbal (mental) nature of the cognitions, as well as their vividness, specificity, and richness.

Adolescent cognitions and behavior (e.g., suicidal cognitions and attempted suicide) have been shown to have long-term implications over the life course (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Kingsbury, Warner, Landry, Clayborne, Islam and Colman2023; Castellví et al., Reference Castellví, Lucas-Romero, Miranda-Mendizábal, Parés-Badell, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Roca, Rodríguez-Marín, Rodríguez-Jimenez, Soto-Sanz and Alonso2017). The left-facing arrow in the figure between attempts and cognitions reflect nonlinear effects of suicide attempts during adolescence in shaping adolescent life, mortality, and suicide cognitions (Oppenheimer et al., Reference Oppenheimer, Glenn and Miller2022).

Lastly, cognitions tend to be shaped by an adolescent’s interpersonal context (e.g., school, family, peers). Thus, the framework encourages a developmental perspective in the consideration of the adolescent interpersonal context in which cognitions operate.

Below, we provide exemplars of specific, testable, developmental hypotheses that can be elicited from the cognition-to-action (CTA) framework, as well as how researchers can act on these hypotheses in the field of adolescent suicide prevention. These hypotheses by no means reflect an all-encompassing list, but provide the reader with immediate next steps in testing the model.

CTA developmental hypothesis #1: not all life, mortality, and suicide cognition content are of equal importance in the prediction of attempts and fatality; there may be healthy mortality cognitions and harmful life cognitions

In our CTA framework, we outline specific life, non-suicidal mortality, and suicide cognitions that may be involved in the transition from cognition to action, both during adolescence and across the life course. However, as described above, the overwhelming focus of the literature has been placed on a sole cognition: active suicidal ideation, without much attention placed on passive suicidal ideations (Van Meter et al., Reference Van Meter, Knowles and Mintz2023), and non-suicidal mortality and life cognitions. Critical for primary prevention is to identify and understand the strengths and direction of associations of passive suicidal, life, and non-suicidal mortality cognitions with adolescent suicidal behavior: what mortality and life cognitions are harmful, and which are healthy, in the prevention of attempted suicide and mortality. For example, the overwhelming assumption in the field is that the presence of mortality cognitions is harmful. However, that assumes that there is no way to think about death that isn’t harmful during adolescence; we hypothesize that adopting an acceptance toward death that highlights the importance of having a life worth living can be protective against suicide (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Reker and Gesser1994). Similarly, life cognitions are often thought to have a positive valence; we hypothesize that having unrealistic positive future thinking could be harmful for adolescent suicidality (Nam & Cha, Reference Nam and Cha2023; Pollak et al., Reference Pollak, Guzmán, Shin and Cha2021).

CTA developmental hypothesis #2: the relative concurrence of suicide, life, and non-suicidal mortality cognitions matters in the prediction of adolescent suicidal behavior

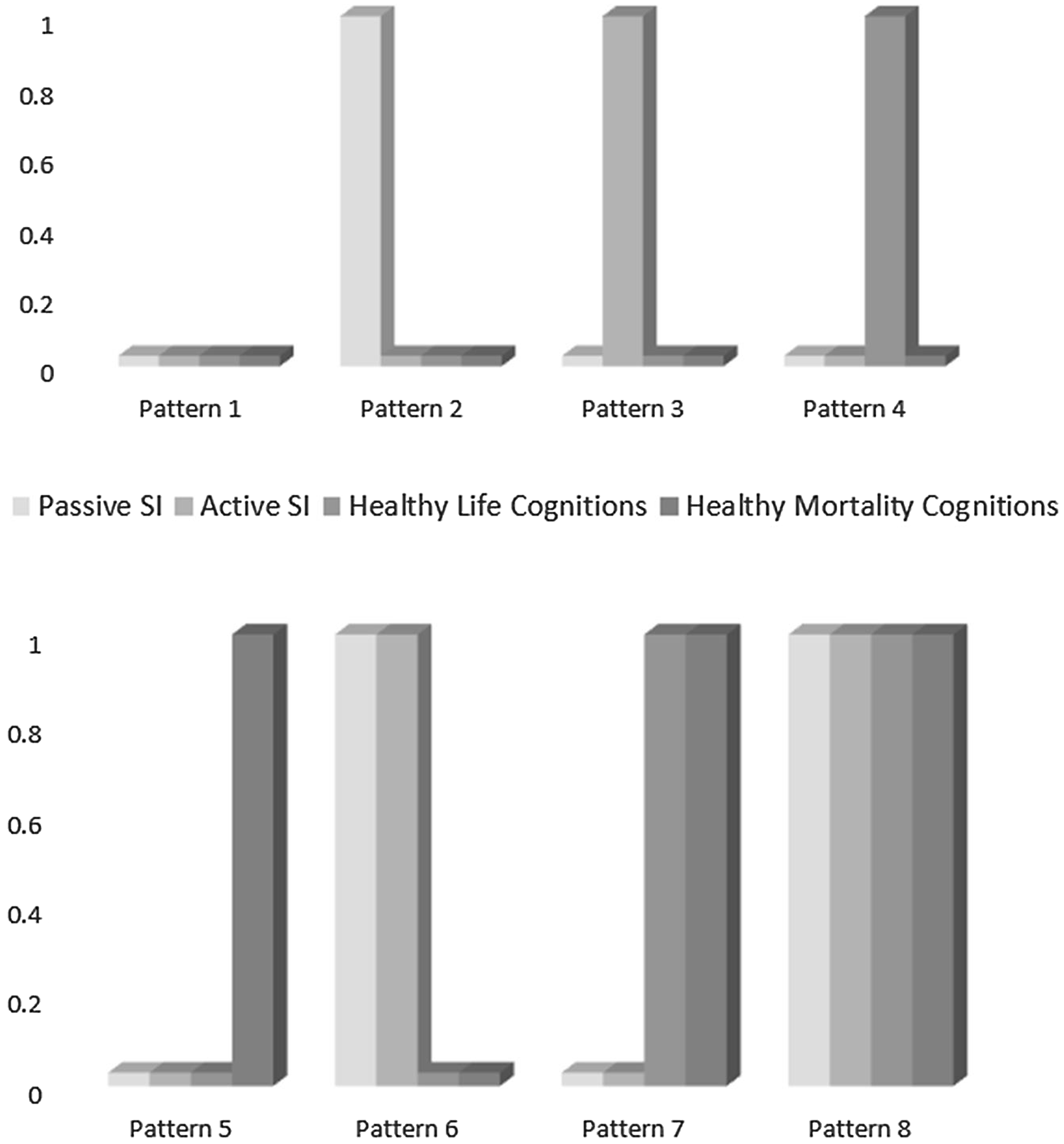

We hypothesize that in analyses and predictions of adolescent suicide attempts and fatality, there is a left out variable error problem, namely: the consideration of the concurrence of mortality and life cognitions. We hypothesize that not all adolescents who attempt and/or die by suicide are the same. Rather, there are different clusters of adolescents with shared life, mortality, and suicide cognition concurrence, and these clusters differ in their risk for suicide. In understanding the pattern of cognitions for each of these groups, we can better facilitate the development of healthy cognitions and dampen the presence of harmful cognitions. In the figure below, we hypothesize what adolescents with these distinct patterns of cognitions may look like.

Figure 5 is a hypothetical example of the patterns of cognitions that may appear in a person-centered analysis of a universal sample of adolescents based on the frequency of passive suicidal ideation (SI), active SI, life cognitions, and non-suicidal mortality cognitions. Note: for simplicity, we are assuming the life and mortality cognitions displayed in this hypothetical analysis are healthy or beneficial cognitions (e.g., meaning in life; neutral death acceptance; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Reker and Gesser1994), and not negative or harmful cognitions (e.g., unrealistic positive thinking; Nam & Cha, Reference Nam and Cha2023; Pollak et al., Reference Pollak, Guzmán, Shin and Cha2021). Again, for simplicity, we hypothesize eight patterns of suicidal, life, and mortality cognitions that could emerge, each with their own relative level of risk for suicidal behavior and prevention approach. Pattern #1 represents adolescents who do not have or report any suicidal, life, or mortality cognitions. Patterns #2 – 5 are the cognition patterns in which only one cognition is present, while Patterns #6 – 8 are the cognition patterns in which cognitions are co-occurring or concurrent.

Figure 5. A hypothetical person-centered analysis of suicidal ideation, life, and non-suicidal mortality cognitions.

In particular, we hypothesize that adolescents in pattern #5 (high passive, high active, low healthy life, low healthy mortality cognitions) are at the most risk for suicidal behavior for two reasons. First, as described above, we hypothesize that suicidal ideations that co-occur are synergistic in nature and result in higher levels of risk (Reference Wastler, Bryan and Bryan2022b, Wastler et al., Reference Wastler, Khazem, Ammendola, Baker, Bauder, Tabares, Bryan, Szeto and Bryan2022a). Second, the synergistic concurrence of suicidal ideations is occurring with low frequencies of healthy life and mortality cognitions together resulting in a risk profile for suicidal behavior (Kirtley et al., Reference Kirtley, Lafit, Vaessen, Decoster, Derom, Gülöksüz, De Hert, Jacobs, Menne-Lothmann, Rutten, Thiery, van Os, van Winkel, Wichers and Myin-Germeys2022). Meanwhile, we hypothesize that pattern #7 (low passive, low active, high healthy life, high healthy mortality) represent adolescents that are the least likely to attempt suicide. These adolescents do not have any suicidal ideations, and instead have a high frequency of healthy thoughts about their mortality and their life. The other patterns we hypothesize lie in between patterns #5 and #7 in their risk for suicidal behavior. Important to note: adolescents in pattern 8 (high passive, high active, high healthy life, high healthy mortality) although high in passive and active suicidal ideation concurrence, also have co-occurring healthy life and mortality cognitions that result in a reduced likelihood to act on their suicidal ideations. We posit that building concurrence in cognitions – namely helping adolescents to form healthy life and mortality cognitions in addition to their unhealthy suicidal ideations – is one way in which existing therapies are effective in reducing the likelihood of suicide attempt among adolescents with active suicidal ideation and represents a novel direction for primary prevention efforts.

CTA developmental hypothesis #3: the mental imagery of adolescent suicidal, life, and non-suicidal mortality cognitions is predictive of adolescent suicidal behavior

As described above, there has been preliminary work that has examined how the mental imagery of active suicidal ideations (e.g., their vividness, richness, degree of detail, visual nature) is associated with attempted suicide more so than for verbal active suicidal ideation alone (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Nesi, Burke, Liu, Spirito, Hunt and Wolff2021; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Ortin-Peralta, Macrynikola, Nahum, Mañanà, Rombola, Runes and Wasee2023). We hypothesize that the same is true for passive, mortality, and life cognitions. In this hypothesis, we posit that the extent to adolescents have mental imagery of harmful life, death, and suicidal cognitions is predictive of the likelihood they attempt and die of suicide. If true, primary prevention approaches could seek to provide adolescents with opportunities to visualize healthy life and mortality cognitions, as well as in reducing the vividness, richness, and degree of detail in already present suicidal cognitions.

Moving from hypothesis to action

In the sections below, we outline how the field can move from these hypotheses to action for adolescent suicide prevention that warrant attention based on our framework.

Person-centered approaches

While the field of suicide has overwhelming utilized analytic approaches that consider variables individually while controlling for one another (variable-centered approaches), person-centered approaches (e.g., latent class analyses) represent one way analytically to consider the grouping of adolescents by patterns of the timing, content, and mental imagery of cognitions in the prediction of suicide behavior and mortality. Figure 5, above, represents one type of output that person-centered analyses can provide in informing the field in how the clustering of cognitions can predict attempted suicide during adolescence.

Ecological momentary assessments

The weakness of both variable- and person- centered approaches lie in their reliance on scales that rely upon long time frames (e.g., past month, past year) in assessing the occurrence/perception of content, timing, and mental imagery of cognitions. EMAs represent a useful approach in examining cognitions within a short time frame and could work to assist researchers in understanding the co-occurrence of life, mortality, and suicidal cognitions. Research that has utilized EMAs has primarily focused on understanding active suicidal ideations (Czyz et al., Reference Czyz, Horwitz, Arango and King2019; Gee et al., Reference Gee, Han, Benassi and Batterham2020; Sedano-Capdevila et al., Reference Sedano-Capdevila, Porras-Segovia, Bello, Baca-Garcia and Barrigon2021). A needed next step in the field is to apply the CTA framework in the collection of data using EMAs.

Grounded theory examinations of the CTA framework

Grounded theory examinations of the CTA framework – using data to iterate on our proposed theory – can be done in two ways. First, formative qualitative and quantitative research can be conducted to understand, for example, (a) what thoughts adolescents have about their life and death and how thoughts change in tandem with thoughts about suicide; (b) how varying profiles of thoughts about life and mortality are associated with reductions in the transition to attempted suicide. The answers to these and other related research questions can both inform the CTA framework and subsequently inform primary prevention programing and intervention development.

Second, existing interventions and therapeutic models that reduce adolescent ideation and behavior may also have utility in informing theory. In particular, Sources of Strength (SoS), an evidence-based program designed to foster resilience via school-wide messaging, has efficacy in shaping adaptive suicide norms, adult connectedness, school engagement, acceptability of help-seeking behaviors, and coping among high-school aged adolescents (Aguilar et al., Reference Aguilar, Espelage, Valido, Woolweaver, Drescher, Plyler, Rose, Bai, Wyman, Kuehl, Mintz and LoMurray2023; Williford et al., Reference Williford, Yoder, Fulginiti, Ortega, LoMurray, Duncan and Kennedy2021; Wyman et al., Reference Wyman, Brown, LoMurray, Schmeelk-Cone, Petrova, Yu and Wang2010). In the delivery of SoS, adolescents identify sources of strength or protective factors that are external (e.g., positive friends, family support) and internal (e.g., spirituality, generosity). Mediated analyses of SoS, or of other evidence-based primary prevention interventions, might have utility to empirically examine life and mortality cognitions as a mediated pathway for the impact of SoS on adolescent outcomes, for example. Instrumental variables estimation coupled with experimental designs may offer insights into causal pathways from life and death cognitions and outcomes for adolescents (see Gennetian et al., Reference Gennetian, Magnuson and Morris2008 for a discussion of this approach applied to welfare and employment experiments).

Similarly, lessons learned from treatment modalities that have long-term impacts on adolescent suicidal ideation could serve to further explicate the CTA framework. In a meta-analysis of 20 years of research, adolescents who received treatment interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents (DBT-A), had greater declines of self-harm, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation than controls (Kothgassner et al., Reference Kothgassner, Robinson, Goreis, Ougrin and Plener2020). Treatment modalities, such as CBT, have components in which cognitive behavioral therapists and patients explore reasons for living and dying, restructure relevant and automatic cognitive processes, and create a hope kit with items that remind adolescents of the important parts of their lives when they are experiencing suicidal ideation (Bryan, Reference Bryan2015). This indicates that treatment modalities foster cognitions about life and death for adolescents who experience suicidal ideation and are successfully navigated to treatment. Furthermore, future research should consider how strategies employed as part of treatment modalities that are efficacious can help to inform the CTA framework and subsequent primary prevention programing to support adolescents in fostering healthy life and mortality cognitions prior to the appearance of treatment indications (i.e., suicidal cognitions).

Addressing the underlying drivers of adolescent life and death cognitions

It is unclear how drivers of suicide attempts and mortality that are tied to the context in which individuals or groups are embedded drive differences in cognitions based on identity: race/ethnicity, gender, sex, or sexual orientation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023b). Future research should seek to understand the role of identity and how adolescent identity formation – the primary task of adolescence – occurs in a context of life, mortality, and suicide cognitions, and how having a marginalized or multiple marginalized identities shape how adolescents consider their lives and mortality. It is also critical to understand how proximal factors such as risk exposure, as well as distal factors, including social determinants of health, that are differentially clustered by race/ethnicity or sexual orientation, are associated with life, mortality, and suicide cognitions (Thimm-Kaiser et al., Reference Thimm-Kaiser, Benzekri and Guilamo-Ramos2023).

Preventing suicidal ideations and fostering concurrent cognitions

In October 2022, 134 national and state organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association (AAP-AACAP-CHA), wrote a joint letter to President Biden urging the White house to issue a National Emergency Declaration to allocate needed funding to ensure all adolescents can access the mental and behavioral health continuum (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2022). AAP-AACAP-CHA’s proposed response to this emergency is largely clinical, namely to increase: access to mental health services, opportunities for screening, and workforce capacity. Or, in other words, mental health treatment as adolescent suicide attempt and fatality prevention.

While treatment as prevention approaches are critical, there is a separate need to address increasing rates of suicidal ideation during adolescence as a target for prevention. We call for primary prevention approaches that seek to address the content, timing, and mental imagery of suicidal ideations (vs. a sole focus on prevention of suicidal behavior) during adolescence – a similar case was made for the urgency of approaches to non-suicidal self-injury that are designed to prevent the onset of self-harm (Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Hinshaw and Bridge2019).

More broadly, we argue for the need of future work to understand how life, mortality, and suicidal cognitions may shape attempted suicide as the next logical step of decades of work in preventing the transition from ideation to action across the life span.

Strengths and limitations of the CTA framework

We highlight six strengths of the CTA framework’s conceptual underpinnings. First, the CTA framework represents one of the few suicide theories to be posited for adolescents, and the first theory, to the authors’ knowledge, that incorporates developmental considerations of cognition specific to adolescence and its role in predicting suicidal behavior. Second, it builds on ideation-to-action frameworks to introduce life and non-suicidal mortality cognitions that warrant attention in the prediction and prevention of suicidal ideation and behavior. Third, the framework moves beyond life and mortality cognitions as protective and risk factors and asserts that they are instead thoughts that have distinct content, timing, and mental imagery with relevance to suicide prevention. Fourth, the CTA framework provides an alternative to the sequential, hierarchical continuum of risk to propose that life, mortality, and suicidal cognitions may be concurrent in nature, which warrants empirical and programmatic attention. Fifth, the framework considers the adolescent’s interpersonal context (e.g., school, family) and hypothesizes that this social context shapes life, mortality, and suicidal cognitions, the characteristics of the cognitions, and suicidal behavior during adolescence. Sixth, the CTA framework is the first theory to state that the cognitions adolescents form and strengthen throughout adolescence about life, mortality, and suicide have real-world implications for cognitions and suicidal behavior throughout the lifespan.