Introduction

South African music, with its rich tapestry of diverse influences and traditions, serves as a unique backdrop for music literacy education. Within this rich culture, however, is a myriad of complexities regarding music literacy education in secondary schools. Much like the complexity of an anagram waiting to be solved, the educational landscape poses a conundrum, and exploring its nuances reveals a dynamic interplay of factors that contribute to the distinctive nature of Music literacy education in South Africa.

Music literacy is a crucial component of the academic subject ‘music’ in the subject-specific curriculum, known as the Curriculum and Policy Statement South Africa – Music as a Subject (CAPS, 2011), providing learners with the tools to understand and appreciate the language of music. The effectiveness of teaching methods in Music literacy has been a subject of interest for researchers and educators alike, facing a unique set of challenges in providing quality Music literacy education.

To address this, exploring the integration of an anagram as a tool to enhance the process of researching Music literacy education in South African secondary schools, has been applied. The metaphorical approach of using the anagrams ‘NAOUIEDCT’ and ‘RCSSEOEUR’ to symbolise the complexities in music education creates a dynamic framework to explore Music literacy education. While this comparison may seem unconventional at first, some intriguing parallels can be drawn.

Anagrams involve rearranging letters to form new words or phrases. Similarly, the music literacy conundrum in South African secondary schools involves rearranging various educational components – such as curriculum, resources, teaching methods and cultural considerations – to create and effective and inclusive music education system. Just as rearranging letters in an anagram requires careful thought and consideration, addressing the challenges in music literacy education requires a multifaceted approach that considers the diverse needs and contexts of students and educators.

The anagrams ‘NAOUIEDCT’ and ‘RCSSEOEUR’ consist of nine scrambled letters which can be unscrambled into different words, also in different languages. These letters, in different combinations, have a magnitude of meanings, for example: ‘NAOUIEDCT’ can be reshuffled to form the words ‘auctioned’, ‘cautioned’ or ‘education’ in English. In French, the same letters spell the word ‘coudaient’ which means ‘folding’ or ‘putting an elbow-bend in it’. In Italian, it spells ‘ineducato’ which translates to ‘uneducated’. The hidden meanings in these anagrams, especially in combination, are illustrative of the depth of meanings and solutions that can be found in reshuffling the letters. This in turn is descriptive of the unravelling of the complexities of the educational system to identify underlying patterns, structures and barriers that may impede access to quality Music literacy education.

This process requires careful analysis, critical thinking and collaboration among stakeholders to find innovative solutions. These anagrams are therefore utilised to illustrate and depict the complex Music literacy education conundrum in South African secondary schools.

Background – setting the stage

South Africa has a rich and diverse musical heritage, with influences from various cultures shaping its vibrant musical landscape. However, challenges in Music Education, such as limited resources and diverse student populations, prove to be challenging to music teachers. In the context of Music education research projects, an ‘anagrammatic lens’ could refer to a metaphorical approach or perspective that involves rearranging and reinterpreting existing concepts, methodologies or findings to reveal new insights or perspectives. Just as anagrams involve rearranging letters to create new words or phrases, an anagrammatic lens in Music Education research involves reconfiguring elements of research in innovative ways to generate novel understandings or solutions.

If one considers the ability to read and write a language as literacy, the anagrams ‘NAOUIEDCT’ and ‘RCSSEOEUR’ are descriptive of the solutions and meanings as ascribed by different languages, contexts and situations. The ability to unscramble the letters and draw meaning from a different order of letters therefor makes the reader the meaning maker. In a South African context, it could therefore be argued that literacy of music is essential for every South African to create meaning in his or her own context and situation.

South African music teachers are facing many challenges regarding the effective teaching and learning of Music literacy. Although it is widely believed, and accepted, that music education should be readily available to all learners (Kodály, 1882–1967), the teaching of Music literacy poses to be a contentious subject. Different scholars have different, and often opposing, views regarding the need and place of Music literacy in music education. Several of these views are underlined by the following questions. If, and whether Music literacy is needed in an African post-colonial context of music education? (Herbst, De Wet & Rijsdijk, Reference HERBST, DE WET and RIJSDIJK2005). Is Music literacy education not elitist and associated with Western Classical Music Education (Akrofi, Smit & Thorsen, Reference AKROFI, SMIT and THORSÉN2007) as opposed to orally transferred music knowledge (Herbst, De Wet & Rijsdijk, Reference HERBST, DE WET and RIJSDIJK2005)? Can the teaching and learning of Music literacy be included in an African Music Education context, while some music teachers believe that African music has a ‘lack of literacy’? This ‘lack of literacy’, which was an interviewee’s opinion in a study by Drummond (Reference DRUMMOND2015), underlines the lack of knowledge most Classical Western Music teachers have regarding African music in general. The sol-fa system (Curwen, 1816–1880) has been “Africanised” over many years and is another colonialist legacy that is often utilised in African choral music (Rijsdijk, Reference RIJSDIJK2003; Leqela, Reference LEQELA2012). Furthermore, the sol-fa system is not the only literacy in play in the concept of Music literacy education in the South African context. As Drummond (Reference DRUMMOND2015) states: ‘it is difficult for me to endorse the view that Western Music literacy is an accepted and unchanging measure for mastering musical skills’. These examples are underlining the palpable problems in the education system regarding Music literacy in South African secondary schools. Music literacy education has been researched within the overarching construct of Music education (Drummond, Reference DRUMMOND2015; Lewis, Reference LEWIS2014; Gordon, Reference GORDON2020), as part of Music as a subject in the Further Education and training (FET) (Gr 10 – 12) phase (Mangiagalli, Reference MALAN2005; Jansen van Vuuren, Reference JANSEN VAN VUUREN2010; Leqela, Reference LEQELA2012; Hellberg, Reference HELLBERG2014) and Creative Arts in the General Education and training (GET) (Gr R – 9) phase (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2004; Herbst, De Wet & Rijsdijk, Reference HERBST, DE WET and RIJSDIJK2005; Malan, Reference MALAN2015). Drummond (Reference DRUMMOND2015) stated that some music teachers believe that African music is ‘to encourage increased participation and are relevant to quotidian life’, while ‘Western music is regarded to be more serious-minded with an emphasis on Music literacy’. Another argument by Drummond (Reference DRUMMOND2015) is that some trained Western music teachers teach indigenous music through Western musical traditions, raising serious issues regarding authenticity. The issue of authenticity in the teaching and learning of music literacy in multiple contexts and genres raises serious questions regarding the true value of Western musical tradition being applied to teach indigenous African repertoire in a school environment. The anti-colonial work of music educators in the United Kingdom seems to support authenticity in the teaching and learning of music literacy. The purpose of de-colonising Music education should be a philosophy of authenticity for all learners of music, in other words providing a richer and more diverse musical experience to learners.

With over a decade of experience, Professor Nate Holder has been advocating for inclusive and diverse music education globally through speaking engagements, writing and consultancy. As an experienced public speaker, Nate has led numerous Continious Professional Development (CPD) training, workshops and lectures for schools, universities and hubs to tackle issues including pedagogy and critical perspectives in music classrooms, departments and boards.

This magnitude of possibilities or complex discourses regarding Music literacy education is not only a definitional conundrum, but also sociological, with widely differing conceptions of what the teaching and learning of Music literacy should, and should not, entail. Given the plurality of views on the issue of Music literacy education, it is not surprising that no real solution exists. The general discourse about Music literacy education is not specific, but rather about colonialism, and political and sociological relevance. In the study by Drummond (Reference DRUMMOND2015), all participants unanimously agreed that Music literacy is a ‘non-negotiable part of the music curriculum’. Thus, definitional discussions regarding Music literacy are the next logical step in the discourse regarding Music literacy in South African secondary schools.

Defining Music literacy in the South African context

Literacy in music and Music literacy offer two complementary, but distinct, ways of understanding Music literacy. Literacy in music refers to ‘the listening, speaking, reading, viewing and creating practices that students use to access, understand, analyse, and communicate their knowledge about music as listeners, composers, and performers’ (Jeanneret, Reference JEANNERET2021). Musical literacy involves the interpretation and meaning making ‘from aural and written musical texts, drawn from a range of cultures, times and locations which use conventional (Mills & McPherson, Reference MILLS and MCPHERSON2015) and graphic notation’. Music literacy is a frequently used term in Music education worldwide, as well as South African context. According to Broomhead (Reference BROOMHEAD2019),‘it enjoys a place of prominence in music instruction, promoting diligence in addressing skills that create independence’. The International Kodály Society (2019) defines Music literacy as: ‘the ability to read and write musical notation and to read notation at sight without the aid of an instrument. It also refers to a person’s knowledge of, and appreciation of, a wide range of musical examples and styles’. Zoltán Kodály (1882–1967) was one of the first advocates of Music literacy teaching and learning, and he believed that Music education should be available to everyone. In the opinion of Lois Choksy (Reference CHOKSY1981), Music literacy is ‘the ability to read, write, and think music’. Estelle Jorgensen (Reference JORGENSEN1981) defined Music literacy as ‘that minimal level of musical skills which enables an individual to function with musical materials’. She further specifies that the term refers more to the intellectual and cognitive elements of appreciation than to the emotional or affective elements. As part of the intellectual element, she identifies two polarities, namely, aural skills or “inner hearing” and rational understanding skills. Broomhead (Reference BROOMHEAD2019) took it a step further and believes that Music literacy entails all the aspects encompassed in the terms: performer, creator, listener, and thinker. Heather Shouldice’s definition (Reference SHOULDICE and CONWAY2014) seems to summarise all the definitions:

‘Music Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, and compute musically, using printed and written music notation materials associated with varying musical context. Music literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their musical goals, to develop their musical knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their musical community and wider society.’

The issues confronting music educators are frequently complex. This is clearly illustrated by various experienced teachers and researchers who share a commitment to the growth and improvement of school music in its many forms.

The definition of Music literacy, however, for this article, will be as described in the official South African Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) document of 2011: the ‘reading, writing and understanding of music notation’. In the next section the positioning and functioning of the specific learning area ‘music literacy’ in the subject ‘Music’ will be clarified.

Music as a subject

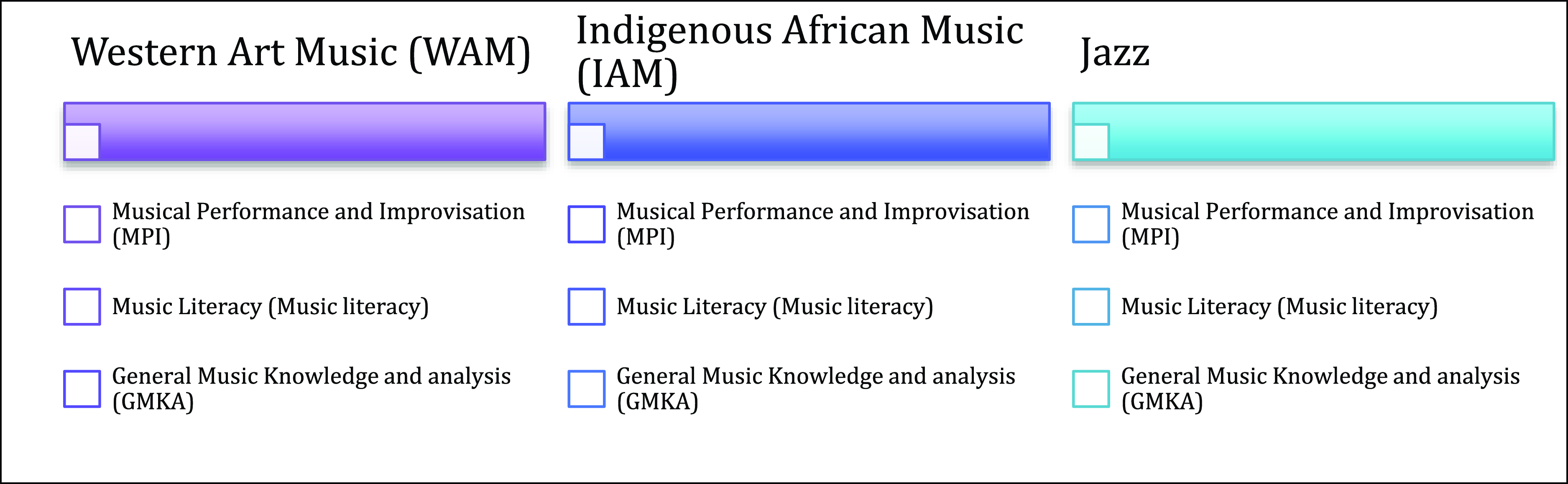

In South African secondary schools, in the Further Education and Training Phase (Gr. 10 – 12), which is the final phase, learners take four core subjects: Home Language, First Additional Language, Mathematics and Life Orientation. Then they are allowed to select three elective subjects, of which Music as a subject could be one. Music, as an elective subject, is subdivided into three elective streams or options, known as Western Art Music (WAM), Indigenous African Music (IAM) or Jazz. Learners select one of these streams. In each of these streams three broad topics are included in the CAPS curriculum: ‘Topic 1: Musical Performance and Improvisation (MPI); Topic 2: Music Literacy (Music literacy); and Topic 3: General Music Knowledge and Analysis (GMKA)’. See Fig. 1.

Figure 1. The three streams (elective) with the three topics in each (CAPS, 2011).

Music literacy, (Topic 2 in each of the streams) is described in the CAPS (2011) document as: ‘Music theory and notation; Aural awareness of theory; Sight-Singing; Harmony; and Knowledge of music terminology’. In Music as a subject, The South African National Department of Education (2011) seeks to ‘provide learners with a subject that creates opportunities to explore musical knowledge’. Critique has been voiced regarding the general planning of Music as a Subject, as well as the explained positioning of Music literacy in the subject of Music. Drummond (Reference DRUMMOND2015) argued that the CAPS (2011) has ‘attempted to organise the curriculum in a way that addresses what might be regarded globally as good quality music education’. She states that the elements of the three streams of Music as a subject (Western Art Music, Indigenous African Music and Jazz) are ‘underspecified’. She further holds that the Western tradition of Music literacy has been reproduced and applied to non-Western traditions to accommodate diversity in the curriculum. Boudina McConnachie (Reference MCCONNACHIE2016) agreed with Drummond that there is a contradiction between the promises of change and the actual curriculum. She claims that in the assessments of the three streams, realistic opportunities to engage and assess IAM and Jazz, in comparison to WAM, do not exist.

Vermeulen (Reference VERMEULEN2009) and Drummond (Reference DRUMMOND2015) posited that WAM is being treated as a ‘separate and complete entity’ whilst IAM is being presented as an ‘integrated’ entity within the overall strategy of organising the curriculum as a balance between developing ‘generic’ and ‘specific’ knowledge skills. Furthermore, Onyeji (Herbst Reference ONYEJI2005) believed that there should be a difference in the notation of African and Western music. These two different notation systems should be learned by all three different streams, and not be isolated to one, as it is different music ‘languages’ that should be able to ‘communicate’. Because of the mentioned disparities, the Music literacy education system in South African secondary schools seems like an impossible and unfathomable conundrum (complex challenge).

Objectives

Music literacy education in South African secondary schools presents a unique conundrum influenced by cultural diversity, limited resources and the need for inclusive pedagogical approaches. To delve into this intricate landscape, a research method incorporating anagrams (symbolic puzzles) has been designed. This approach aims to unravel the complexities of Music literacy education in South African secondary schools, much like solving a multifaceted puzzle. In this article, the term conundrums will be specifically used to describe the complex challenges and the term anagram will be used to create intricate puzzles. The objectives of this research are outlined, emphasising the need to decipher the symbolism of the anagrams ‘NAOUIEDCT’ and ‘RCSSEOEUR’ and unravel the complexities within South African Music literacy education.

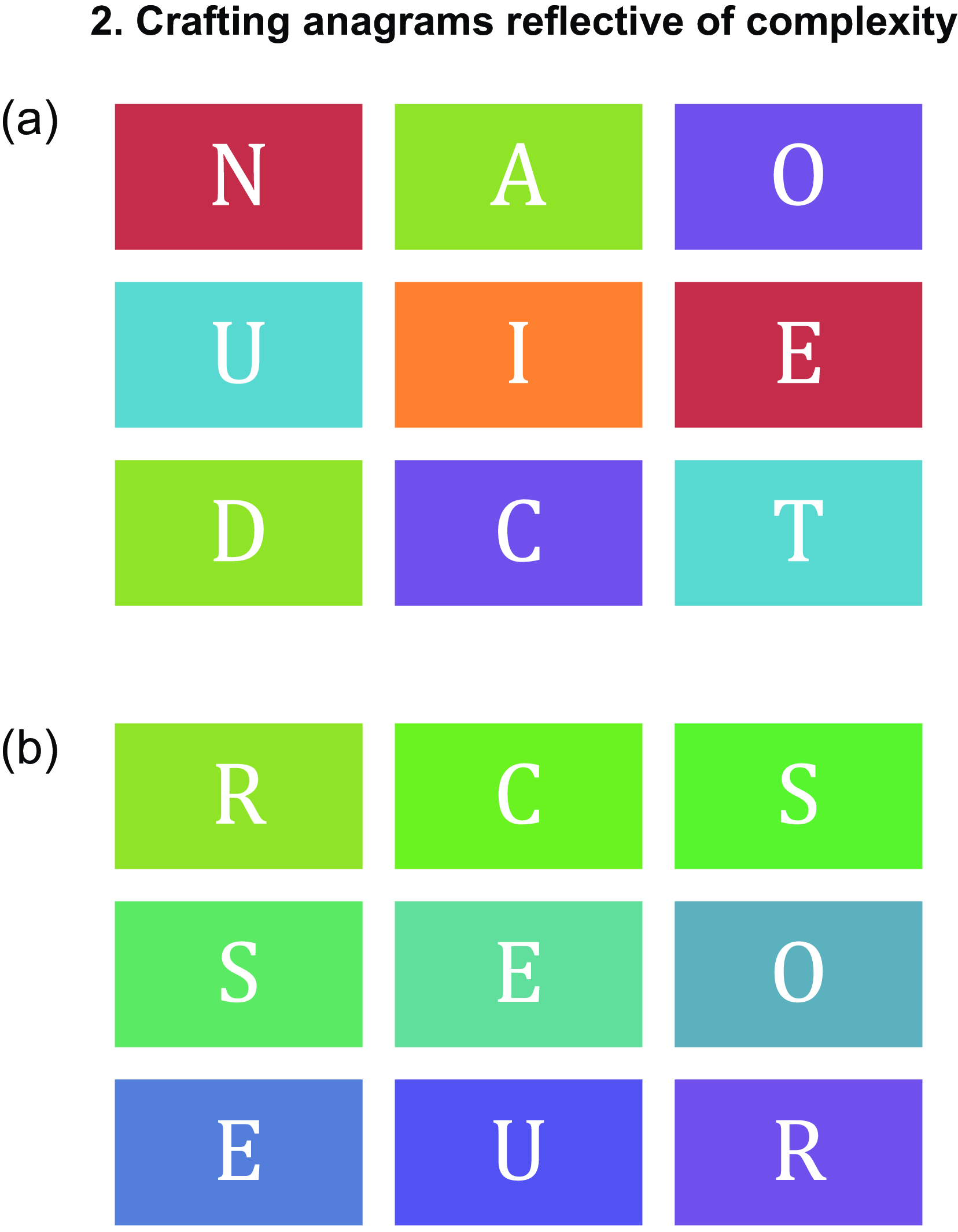

Crafting anagrams reflective of complexity

A typical conundrum consists of nine letters that have been scrambled into an anagram. These nine letters have to be reshuffled and unscrambled to form a word/words. In the reshuffling and unscrambling of the two anagrams ‘NAOUIEDCT & RCSSEOEUR’ the following words can be formed:

‘NAOUIEDCT’ deciphers to: CAUTIONED, AUCTIONED, ACTIONED OR EDUCATION.

‘RCSSEOEUR’ deciphers to: RECOURSE, RESCUERS, RESOURCES.

In combination, the solutions to the two conundrums are even filled with more hidden meaning, making it increasingly exciting and meaningful: ‘CAUTIONED RECOURSE’; ‘A[U]CTIONED RESCUERS’ and ‘EDUCATION RESOURCES’.

Why anagrams?

The anagrams ‘NAOUIEDCT’ and ‘RCSSEOEUR’ symbolise complexity. This reflected complexity offers tools for understanding and addressing the challenges of imparting Music knowledge in a diverse environment. It explores the diversity within South African secondary schools, examining the challenges and advantages of multicultural classrooms. Anagrams are employed as symbolic puzzles that encapsulate the challenges and intricacies within the South African Music literacy education system. Each anagram serves as a metaphorical representation of a specific aspect or challenge faced by educators and students in the pursuit of effective Music Education. Researchers design anagrams that correspond to key themes within the Music literacy education conundrum, such as cultural diversity, limited resources, language barriers and community engagement. Anagrams are carefully crafted to mirror the linguistic and cultural diversity present in South African secondary schools.

Integration with curriculum components

Anagrams are strategically aligned with components of the Music literacy curriculum, ensuring relevance to the educational objectives and content covered in South African schools. This integration facilitates a direct link between the anagrams and the real-world challenges faced by educators and students.

Longitudinal study design

The research method adopts a longitudinal study design, allowing for the observation of changes and developments over an extended period. Anagrams are periodically introduced, providing an evolving narrative of the challenges and successes in South African Music literacy education.

The unresolved anagram

The unresolved anagrams become a metaphor for the multitude of complexities present. Thus, anagrams, by their nature, represent symbolic puzzles waiting to be solved. In the context of South African Music literacy education, anagrams become powerful tools for encapsulating and deciphering the complexities inherent in the educational system.

Unravelling NAOUIEDCT

The acronym NAOUIEDCT encapsulates the linguistic enigma in music education. The diversity inherent in South African secondary schools, represents a myriad of languages, each contributing to the rich cultural mosaic of the nation. In this article, the teaching and learning of Music literacy in South African secondary schools are depicted as two complex conundrums: NAOUIEDCT & RCSSEOEUR. A conundrum, as aptly described by Kilroy Oldster (Reference OLDSTER2016), is the ‘mysteries of life’ encountered by individuals in a ‘world composed of competing ideologies and agents of change’. He claims that the competing ideologies include ‘political, social, legal, and ethical concepts’, while agents of change include ‘environmental factors, social pressure to conform, aging, and the forces inside us’. A conundrum in literary terms (Merriam-Webster.com, 2019) is described as a difficult problem, one that is ‘impossible or almost impossible to solve’. It is described as ‘an extremely broad term that covers any number of different types of situations from moral dilemmas to riddles’.

In the Music literacy conundrum, the competing ideologies and agents of change are visible when the current political, social, legal and ethical concepts in South African secondary schools are taken into consideration. Change is a constant factor in the lives of teachers, learners and management teams, and includes environmental factors such as poverty, cultural background, and social pressure. Various authors, amongst others Leqela (Reference LEQELA2012) and Herbst, De Wet and Rijsdijk (Reference HERBST, DE WET and RIJSDIJK2005), describe the South African Music education environment as intricate and problematic with an ‘immense amount of diversity’ (Rodger, Reference RODGER2014). Furthermore, it is described as consisting of recurrent interdependent variables, having an impact on the quality and delivery of Music education. In these studies, as well as other scholarly studies conducted by Vermeulen (Reference VERMEULEN2009), Christopher Klopper (Reference KLOPPER2004, Reference KLOPPER2005) and Khulisa (2002, 2003), the variables were identified and listed.

The documented lists of researched and identified variables are extensive and exhaustive, slightly subjective, and do not lead to any conclusions or solutions. It indicates that nearly identical variables are emerging from different studies worldwide, but these studies do not lead to possible solutions. The gap in the literature is, therefore, to develop a structure or framework that can bridge the listed variables and a possible solution to the problem. The challenge is, however, to find a suitable structure in which to systematically organise these variables.

Decoding RCSSEOEUR

Limited resources pose a significant hurdle in the pursuit of quality Music Education. The anagram maze of ‘RCSSEOEUR’ represents the resourceful strategies needed to overcome these challenges and foster an environment where Music literacy can thrive.

Resource disparities in South African secondary schools

Disparities were found in the access to available resources such as musical instruments, sheet music and technology across different schools. General financial empowerment influences student engagement and quality of teaching and learning in different classrooms of various schools. This hints at the challenges posed by limited resources in many South African schools. It points to a disparity in access to musical instruments, sheet music and technology, creating a puzzle that educators strive to solve to ensure an equitable learning experience for all students.

Innovative solutions and resource mobilisation

Innovative solutions and resource mobilisation strategies are employed by multiple educators to overcome limitations. These success stories of schools that have creatively addressed resource constraints in their music programs, are discussed as narratives as part of the qualitative semi-structured interviews.

Shuffling the anagram elements of South African music literacy education

Imagine South African Music literacy education is an anagram, where the shuffling of elements mirrors the intricate process of understanding and learning music. Deciphering the conundrum or challenges and examining the key components unravel the layers that contribute to the unique harmony of South African music education.

Cultural diversity

South Africa’s cultural diversity is a cornerstone of its musical identity. The anagram reflects the challenge of navigating a curriculum that must embrace the vast array of musical traditions, from the rhythmic beats of traditional African drums to the harmonies of Western classical music. The ‘Cultural Diet’ underscores the need for a balanced and inclusive Music Education that nourishes students with a diverse musical menu.

Integration of technology

The integration of technology is a critical aspect of modern education. It emphasises the ongoing efforts to incorporate technology into Music literacy education. It suggests a deliberate weaving of digital tools into the fabric of music education, enhancing accessibility and providing new avenues for creative expression.

Language barriers

Language diversity in South Africa adds an additional layer to the educational puzzle. It encapsulates the linguistic challenges students may face, calling attention to the importance of clear communication and the development of inclusive instructional strategies that transcend language barriers.

Community engagement

This highlights the role of community engagement in Music Education. It emphasises the need for collaborative efforts between schools, local communities and cultural institutions to enrich the educational experience and foster a sense of shared ownership of musical heritage.

After a thorough literature review, it was evident that this perceived problem is not only an isolated issue, but an impinging reality nationally as well as globally. To fully recognise and understand Music literacy education in South African secondary schools, as well as the variables influencing it, a global account of the same phenomenon, is necessary. Klopper (Reference KLOPPER2005) claimed that ‘certain elements of education reform and transformation are not unique to South Africa but rather generic throughout the African continent’.

Klopper (Reference KLOPPER2003, Reference KLOPPER2004, Reference KLOPPER2005) researched and tabled variables that have been influencing and impacting the effective teaching and learning of Music literacy. That was a result of a research project (2002) initiated by the Pan African Society for Musical Arts Education (PASMAE). This project had the objective to improve collaboration between music educators throughout Africa. The task force leading this research project documented problems (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2004) that were experienced by music educators in Africa regarding the teaching and learning of Music.

Four common problem areas, ‘evident in all the countries’ research’ were tabled (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2003), and these four according to Klopper (Reference KLOPPER2004) are:

• Curriculum issues, regarding changes and policy.

• Lack of facilities and resources.

• Skills, training and methodology of practicing educators in schools in and higher education institutions and

• The societal role of the Arts.

These four common problems tabled by the task force encapsulate the deeper underlying factors impacting on effective teaching and learning of Music literacy. In this article, the variables influencing on the teaching and learning of Music literacy are focused on, investigated and described, as part of the South African Music Education environment.

In several studies outside South Africa, the quality of Music Education and the factors or variables influencing this quality have been researched. In China, Yu and Leung (Reference YU and LEUNG2019) tabled four main factors affecting the implementation of the new Music Education curriculum in China. These were first and foremost the student’s ability and quality, then the school’s facilities and equipment, followed by the extent to which music was prioritised within the school, and lastly the teacher’s ability and teaching philosophy.

A survey conducted by the Australian Council of State School Organisations (ACSSO), wherein parents were asked to give their viewpoints on which factors they felt were preventing good quality music teaching and learning in schools, highlighted the following problems:

-

No academic and philosophical support of music.

-

Some curriculum frameworks do not specifically mandate music and musical experiences.

-

Lack of qualified and experienced teachers in most areas.

-

Little evidence of cross-cultural links in music and musical experiences in schools.

-

Lack of specific and practical, teacher-friendly teaching materials.

-

Pressure on learners to meet literacy and numeracy benchmarks (ACSSO, 2005).

The following collective variables were found in studies conducted by the Alberta Education research group (Canada, 1988); Klopper (South Africa, 2004); Khulisa (South Africa, 2002) and in Australia (Lierse, Reference LIERSE2006). These studies included research into the overall quality of music education (Lierse, Seares Report), which variables may have an impact on Music education in South Africa (Klopper), and specifically which variables affected the quality of music teaching in the national curriculum (Khulisa). The found variables, of which most were common between studies in different countries, are:

-

Multiple overload guidelines (Alberta Education, 1988).

-

School Governing Body and community support (Alberta Education, 1988).

-

Parental involvement (MacMillan, Reference MACMILLAN2004).

-

Time and line monitoring (information system) (Alberta Education, 1988).

-

Clarity and need for change (Alberta Education, 1988).

-

Quality (and lack of) and the availability of materials, resources and support (Alberta Education, 1988; Vakalis, Reference VAKALIS2000; Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2008).

-

Principal’s role and support, school governance and leadership (Alberta Education, 1988).

-

Consultant role and support (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

The quality and amount of in-service assistance for teachers (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Inadequately trained teachers (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Inadequacy of orientation courses (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Difficulty in understanding new concepts (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Teachers lacking in comprehensive musicianship and musical competencies (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2008).

-

Teacher–teacher interaction (Alberta Education, 1988).

-

Availability and use of external resources (Alberta Education, 1988).

-

Teaching and learning (Concina, Reference CONCINA2015).

-

Language issues (in South Africa especially) (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Transforming syllabi (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

School environment (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Change in management (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

School ethos (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Financing music programmes at schools (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

General ignorance of the cultures of the different population groups (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Large classes (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Music educational approaches and methods (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

-

Curriculum development (Klopper, Reference KLOPPER2005).

As can be seen, universal variables have been found in a substantial number of studies.

Resolving the anagram for harmonious music education

Now that the anagrams have been unravelled, how can South African music literacy education be reshaped for a harmonious blend of cultural diversity, limited resources, technology integration, language inclusivity and community engagement? In the aim to unscramble lists of variables, a computer-aided Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) was carried out making use of ATLAS.ti™ Version 9 (hereafter ATLAS.ti). ATLAS.ti is qualitative data analysis research software (Soratto, Pires & Friese, Reference SORATTO, PIRES and FRIESE2020). Computer-aided TCA consists of different phases, of which ‘becoming familiar with the data’ is the first phase, the ‘pre-analysis’ phase (Soratto, Pires & Friese, Reference SORATTO, PIRES and FRIESE2020). The scholarly documents entailing variables and factors influencing music literacy education in a worldwide as well as South African context were added to the project and consequently grouped into different document groups. Memos were written and initial codes were defined.

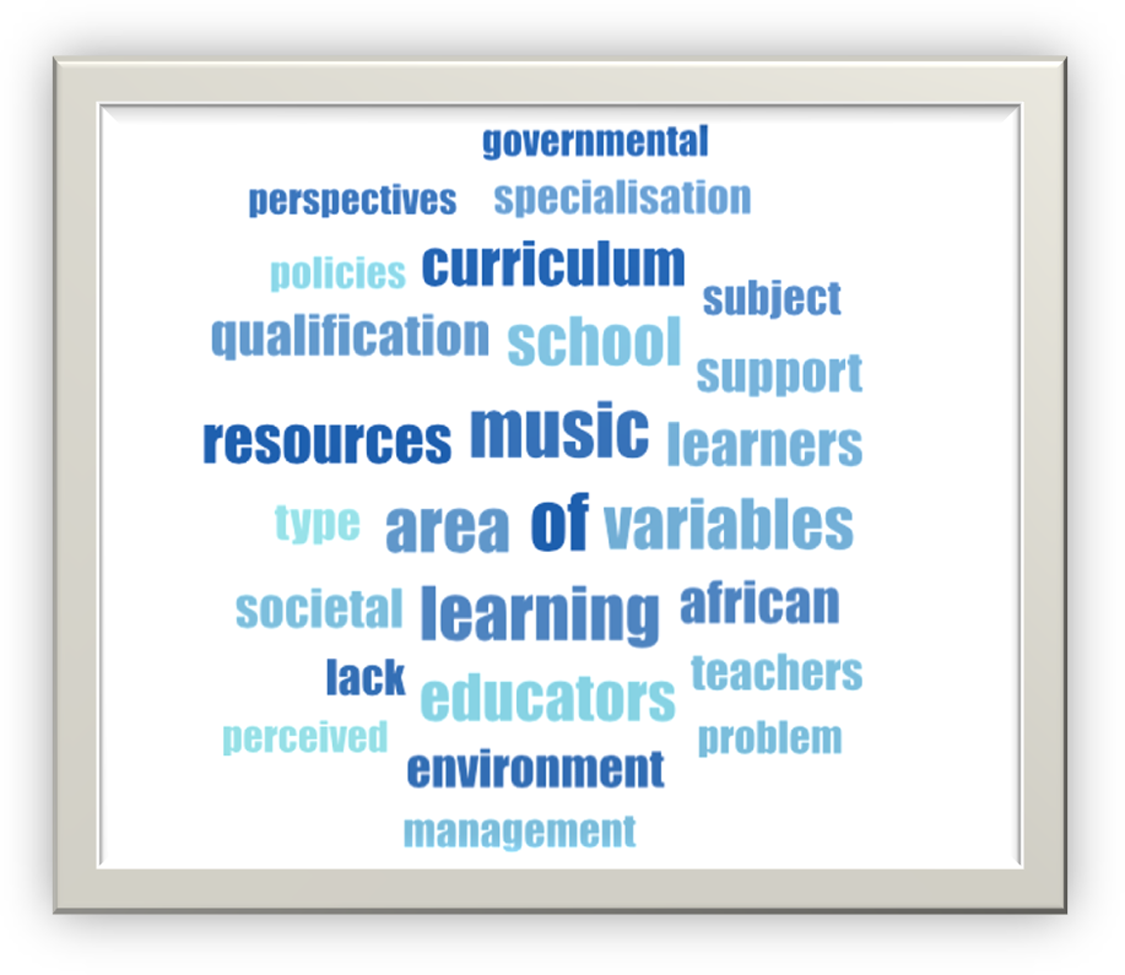

In the second phase of the TCA, the collected material was explored, and quotations were created. The study by Klopper (Reference KLOPPER2005) was used as a defining and pivotal document in this study. Klopper (Reference KLOPPER2005) claimed that the three main categories in his research concerning the variables are: ‘human resources, physical resources and the societal role of the arts’. Building on that, a word list was created of Klopper’s study, significant words were selected as initial codes and a word cloud was created. The word cloud is a visual representation of the most frequent and relevant terms and words used in Klopper’s study. This was part of the second phase of TCA. In the investigation of the Word Cloud, Fig. 2, the six most prominent constructs were chosen to serve as initial categories for the codes.

Figure 2. (a) A typical conundrum, unscrambled it can decipher to: EDUCATION; CAUTIONED; or A[U]CTIONED (Jansen van Rensburg, Reference JANSEN VAN RENSBURG2022). (b) A typical conundrum, unscrambled it can decipher to: RESOURCES; COURSERS; RECOURSE; and RESCUERS (Jansen van Rensburg, Reference JANSEN VAN RENSBURG2022).

After the codes were created and applied the third phase of TCA started, where different analysis tools were applied. Quotations, codes and memos were interpreted on a conceptual level. These six main categories have been derived from a preliminary coding of themes found in previous research, public records including policy statements and governmental reports, student textbooks and the national CAPS curriculum as described by Bowen (Reference BOWEN2009). The final six categories that were chosen are: Resources, Teachers, Curriculum, Learners, Management and Environment. The researched variables have been analysed and sorted according to these six categories.

Resource mobilisation

Music teachers can advocate for increased funding and support for music education, especially in schools facing resource constraints. Foster partnerships with businesses, community organisations and government initiatives to provide schools with the necessary musical instruments, technology and resources.

Teacher efficacy in specialisation

Various recommendations have been made, reiterating the recommendations of Mwila (Reference MWILA2015: iii) that ‘regular and deliberate promotion of in-service teacher training courses for Music’ and ‘a clear policy on music education’ should and would ‘encourage the state of Music Education’.

Inclusive curricular design

Multiple role players can be contacted to develop a curriculum that celebrates the diversity of South African music, incorporating traditional and contemporary elements. This can evolve to create adaptable lesson plans that cater to varied learning styles, ensuring that students with different musical backgrounds can find resonance in the curriculum.

Multilingual learners in various schools

The reality in South African schools is a rainbow mix of multicultural and multilingual students. However, this multilingualism in class creates stress for all, as the common language that we use in schools is English. One solution can be to recognise linguistic diversity within classrooms and provide multilingual instructional materials. Encourage the use of local languages in music education, fostering a deeper connection between students and the material.

Digital integration for accessibility

The ideal situation is to embrace technology as a tool for widening access to Music Education. The development of online platforms, interactive apps and virtual resources makes learning music more accessible, particularly in remote or underserved areas.

Management community-centric programs

Community partnerships can bring musicians, artists and educators into schools. The opportunities to organise community events, performances and workshops can create a sense of shared musical heritage and strengthen the ties between schools and their local communities.

Environment

Herbst, De Wet and Rijksdijk (Reference HERBST, DE WET and RIJSDIJK2005: 273–275) described the South African MusEd environment as intricate and problematic with an ‘immense amount of diversity’ (Rodger, Reference RODGER2014). Ever-changing environments in schools – both government and privately owned. In addition, music teachers, managers and the community have different points of view regarding the place and value of MusLit education in the school context.

Narrative stories

The collected narrative data (semi-structured interviews with eight South African music teachers) consisted of their unique experiences regarding the teaching and learning of MusLit. Narrative inquiry concentrates on a phenomenon, for example, the MusLit conundrum, through the storied experiences of the participants, in this case, the MusLit teachers. Their stories are being told and retold to gain an understanding of, and new insight into, the MusLit conundrum. Narrative Inquiry as a research methodology in MusEd assists in bridging the gap that exists between the found variables impacting effective MusLit education and possible improvements.

Symphony of conclusive and future possibilities

In conclusion, the symbolism of the anagram puzzles ‘NAOUIEDCT’ and ‘RCSSEOEUR’ provides a unique and insightful perspective on the complex Music literacy education challenging conundrums in South African secondary schools. The (un)resolved nature of these anagrams becomes a metaphor for ongoing exploration, adaptation and improvement within the educational landscape. By embracing and incorporating anagrams into the research process, educators and researchers can unravel the layers of complexity, ultimately harmonising the diverse elements at play in Music literacy education.

In this interpretive qualitative study, previously researched scholarly documents were used to gather information regarding the possible variables impacting effective Music literacy education. There are numerous studies on the variables impacting the effective teaching and learning of Music literacy, as well as curriculum implementation and improvement, but only a small number of studies on the link between these two fields of study. Furthermore, many studies are emphasising the importance of Music Education, as well as the general decline of the teaching and learning of Music literacy in Music Education, but again not enough on the combination of these two phenomena.

The first research question: ‘Which variables have an impact on the South African Music literacy Education Conundrum?’ was answered by a comprehensive content analysis of previous scholarly research. The Word Cloud (Fig. 3) was the accumulation of all these lists of variables. Because of the length and extensiveness of these variables, the term Music literacy conundrum was coined for this broad context. To organise the Music literacy conundrum systematically, a computer-aided TCA was implemented and applied both on a descriptive and conceptual level of analysis.

Figure 3. Word Cloud – Klopper (Reference KLOPPER2005) variable research study.

This answered the second research question: ‘How can we systematically organise these variables to be utilised in future research projects?’ The results of this study thus helped towards the articulation of qualitative variables that are salient to the Music literacy conundrum. In this study, firstly, a thorough and concise list of variables influencing the effective teaching and learning of Music literacy as stipulated in the national CAPS (2011) was compiled. Secondly, a computer-aided TCA was constructed to organise these variables systematically in an understandable manner. This summary of variables/word analysis, document analysis as well as empirical narrative stories and the findings in a South African context as illustrative of the Music literacy conundrum can further be used to investigate the teaching and learning of Music literacy in different settings and scenarios. The anagram serves as a metaphorical reminder that, with careful consideration and creative approaches, the complexities of music education can be transformed into a masterpiece of inclusivity, accessibility and cultural celebration. As the puzzle pieces come together, the result is not just an educational system but a symphony of possibilities that empowers students to appreciate, create and contribute to the rich tapestry of South African music for generations to come. In the possible solution to the Music literacy conundrum, it could be claimed that Music literacy might be the vehicle that a child in Africa needs to understand the huge diversity of music found not only on the African continent but also on a global scale. The possibilities of these anagrams as a descriptive and visual tool, this approach offers educators and students exciting new ways to explore, symbolise and visualise the world of music education.

Funding statement

The author(s) received financial support from the University of Pretoria for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ronella Jansen van Rensburg is a dedicated and experienced music education specialist, researcher and teacher. She finished her thesis regarding the Music Literacy conundrum in South African secondary schools (University of Pretoria). In 2021, she received the ‘Best PhD Research in Progress’ award at the annual Faculty of Education Research Indaba. She holds a Master’s Degree in Music (cum laude) and received the Fanie Beetge award for the best academic achievement at the Faculty of Music (UFS) for both 2005 and 2006. Two articles were published: ‘Critical perspectives on Emotional Intelligence and Music Performance Anxiety’ and ‘The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Music Performance Anxiety: and Empirical Study’. She maintains an active private music studio, ScoreS2Duo, in Stellenbosch CBD, specialising in piano, keyboard and music theory lessons.

Ronel De Villiers The research focuses on Higher Education Multicultural Musicking practices and programme content. I have won numerous teacher education accolades from the University of South Africa (2011–2013), the Dean’s Award for Best Research Achiever (2021) and the Dean’s Award for Excellence in Music Education Teaching (2013). As a Senior Music Education lecturer, I supervise multiple MEd and PhD students and am an external examiner for other South African universities. I also serve on the Creative Arts panel for the South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). The Vignette research in South Africa and Austria resulted from a post-doctoral visit from 2018 to 2019 at Innsbruck University and the Mozarteum. I am an Editorial Board member of the International Journal of Music Education (IJME) as well as the Pan African representative for the History Society Committee (HSC) of the International Society of Music Education (ISME). I serve on the Inclusive Education Committee of UNESCO.