Introduction

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) approach highlights the role of environmental exposures in early life, including nutrition, especially during the utero period, that can permanently affect health outcomes and risk of disease later in life. Reference Gluckman, Hanson and Buklijas1 The body of evidence supporting the DOHaD approach is based on epidemiological and animal studies, Reference Fleming, Watkins and Velazquez2,Reference Dahlen, Borowicz and Ward3 the former providing knowledge on the role of nutrition in the development of disease, and the latter proposing mechanisms causing the alterations that may influence both individual, inter- and transgenerational effects.

Recently, the DOHaD approach has also emphasized the importance of health behaviors during the reproductive years for parents-to-be – before life starts – namely in the preconception period. Reference Barker, Dombrowski and Colbourn4–Reference Hanson, Poston and Gluckman6 Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Heslehurst and Hall5 have proposed three definitions of the preconception period spanning from the biological perspective, covering days to weeks before embryo development and maturation; the individual perspective, covering weeks to months before pregnancy; and finally, the public health perspective, covering months to years prior to pregnancy. The duration of the preconception period, defined from the public health perspective, is characterized by large individual variation, as some reproduce as early as in adolescence, whereas others have children in midlife or even as older adults.

Utilizing the preconception perspectives faces a challenge since not all pregnancies are planned. Globally, the incidence of unintended pregnancies among all pregnancies was estimated at 48% (46%–51%) in 2015–2019. Reference Bearak, Popinchalk and Ganatra7 In Norway between 2008 and 2010, more than one in five pregnancies (21%) was reported to be unintended. Reference Lukasse, Laanpere and Karro8 At an average of 6 months of pregnancy, the distribution of age groups were as follows: 24% were under 25 years old, 34% were aged 25–30 years, 27% were aged 31–35 years, and 14% were aged over 35 years (non-country specific, including Belgium, Iceland, Denmark, Estonia, Norway, and Sweden). Reference Lukasse, Laanpere and Karro8

The Global Burden of Disease study has quantified the impact of dietary risks on health, based on data from adults aged 25 years or older. Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay9 Data show that an unhealthy diet is a major risk factor for non-communicable diseases, and that there is a large potential to improve diet quality, as it is a modifiable behavior. Globally, Afshin et al. Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay9 found that the consumption of nearly all healthy foods and nutrients were suboptimal among adults ages 25 years or older in 2017. The largest discrepancies between current and optimal daily intake were observed for nuts and seeds, milk, and whole grains. At the same time, global daily intake of unhealthy foods and nutrients all exceeded optimal levels, particularly for sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), processed meat, and sodium. These dietary trends are also reflected in Western Europe. Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay9 The consumption of healthy foods show that the intake of milk and calcium is higher in Western Europe compared to global intakes in 2017, but that the consumption of legumes and whole grain is lower. For the unhealthy foods, Western Europe show close to double the intake of both red meat, processed meat, and SSB compared to the global intake in 2017.

For young people in the preconception period, diet quality may be even less optimal. This is because the transition into emerging adulthood, namely from the end of adolescence to being a younger adult, is observed to be associated with deteriorating eating habits Reference Stok, Renner, Clarys, Lien, Lakerveld and Deliens10 and weight gain. Reference Akseer, Al-Gashm, Mehta, Mokdad and Bhutta11 The negative changes in diet in this period of life are associated with two key life transition phases: leaving the parental home and leaving education, Reference Winpenny, van Sluijs, White, Klepp, Wold and Lien12 and they may be important periods to target in improving preconception diets.

Public awareness of the critical preconception period in which diet may influence the risk of future disease in future children is an important starting point to improve preconception diet. Although the DOHaD approach is well recognized in the scientific society, little is known about the general populations’ knowledge about it. Only a few studies have reported results of the public’s understanding of the DOHaD approach, Reference McKerracher, Moffat, Barker, Williams and Sloboda13–Reference Valen, Øverby and Hardy-Johnson16 and very little is published on DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and diet quality. However, knowledge of the DOHaD approach was observed to be positively associated with diet quality in a sample of pregnant Canadian women in a study from 2020. Reference McKerracher, Moffat and Barker17 So far, these studies on the DOHaD approach have focused on women only, even though preconception nutrition and health behavior are believed to be of importance to all individuals of reproductive age, regardless of gender. Reference Barker, Dombrowski and Colbourn4,Reference Hieronimus and Ensenauer18,Reference Brown, Mueller and Edwards19 Moreover, nutritional epidemiological studies that include paternal preconception in a wider sense are also scarce, despite the emerging evidence of its importance. Reference Soubry20–Reference Billah, Khatiwada, Morris and Maloney22

The aims of this paper were to describe knowledge of the DOHaD approach (DOHaDKNOWLEDGE) and diet quality in a Norwegian preconception population, to assess if DOHaDKNOWLEDGE was associated with a Diet Quality Score (DQS), and to assess gender difference in those above.

Methods

Study design and study population

This study used baseline data from the PREPARED research project, Reference Øverby, Medin and Valen23 a digital randomized controlled trial aimed at improving the diet of preconception young adults in Norway and the health outcomes of the participants’ future offspring. The PREPARED research project adopts a public health perspective on preconception, in line with the definition by Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Heslehurst and Hall5 , targeting both men and women regardless of pregnancy planning. Reference Øverby, Medin and Valen23 Recruitment occurred from October 2021 to January 2023 using social media advertisement on Snapchat, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. Norwegian preconception men and women aged 20-35 years, without biological children, literate in Norwegian/Scandinavian language, with access to a smartphone or other digital device were eligible for participation. A lottery of ten gift cards worth 5000 NOK (approximately 500 €) was used as an incentive to recruit participants.

Baseline data were collected using a digital questionnaire tool created with nettskjema.no, a survey solution developed and hosted by the University of Oslo ([email protected]). Participants were asked to provide sociodemographic background information (55 questions) (the variables gender, age, mother tongue, height, weight, and level of education were used in the current study), followed by a DOHaD knowledge questionnaire (5 questions) and questions about their dietary habits, including a 33-item dietary screener (MyFoodMonth 1.1) (54 questions in total). All questions in the questionnaires were obligatory, except the question about their body weight. All data were stored, and analyses were performed on the Services for Sensitive Data (TSD) facilities, operated and developed by the TSD service group at University of Oslo, IT-Department (USIT) ([email protected]).

Figure 1 presents a recruitment flowchart for the baseline data of the PREPARED study. Of the 1437 individuals who wanted to participate in the study, 75 were excluded due to ineligibility (did not meet the inclusion criteria and other reasons (duplicates and participants in the pilot study)). The descriptive statistics of the study sample included 1362 eligible participants. Six participants who identified themselves as having a nonbinary gender (identifies as a gender not solely male or female) were excluded from data analyses, resulting in 1356 participants (1201 women and 155 men).

Figure 1. Recruitment flowchart for the baseline data in the PREPARED study.

DOHaDKNOWLEDGE

DOHaDKNOWLEDGE was evaluated using five statements about the long-term influences of parental and/or grandparental health and behavior during periconception and the prenatal and perinatal period on children’s health, with a focus on nutrition, developed by McKerracher et al. Reference McKerracher, Moffat and Barker17 A 5-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree), was used for each of the statements, summarized into a DOHaDKNOWLEDGE scale. The DOHaDKNOWLEDGE scale ranged from 0 points, indicating no knowledge with the theory of the DOHaD approach, to 20 points, indicating very strong knowledge. Reference McKerracher, Moffat and Barker17 The statements were translated into Norwegian using a standard forward-backward translation process, ensuring that the meaning was maintained. Statements made in the first person were changed to the third person to better suit a preconception population including both men and women, for example, phrases such as “what I eat during pregnancy” were changed to “what a woman eats during pregnancy”.

Aspects of diet quality and DQS

Aspects of diet quality and a DQS were derived from MyFoodMonth 1.1, a non-quantitative dietary screener. Reference Salvesen, Wills, Øverby, Engeset and Medin24 The dietary screener assesses the intake of 33 food items during the previous month (30 days) using ten frequency categories ranging from “never” to “6 or more per day”. The dietary screener has previously been validated in a Norwegian sample of young adults and showed satisfactorily ranking abilities, compared to a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire. Reference Salvesen, Wills, Øverby, Engeset and Medin24

Aspects of diet quality is presented as ordinal ranked frequency of intake data for single food items (e.g., alcoholic beverages) and pooled food items (e.g., iodine-rich foods). The frequencies of intake from the dietary screener were recoded to four and five categories to simplify data presentation.

A DQS consisting of ten components was derived from 19 food items from the dietary screener. The DQS assign points using a weighted scoring from 0 to 10 points relative to health benefits associated with the frequency of intake for the respective food items, that is, a higher score indicates a healthier diet, previously described in detail. Reference Salvesen, Wills, Øverby, Engeset and Medin24 The total DQS ranged from 0 points, indicating low diet quality, to 100 points, indicating high diet quality.

Analysis

Descriptive data for age, body mass index (BMI), level of education, ethnicity, DOHaDKNOWLEDGE, and DQS were presented for the total sample and split by gender. The continuous variable BMI was recoded into categories: underweight (<18.5), healthy weight (18.5–<25), overweight (25–<30), and obesity (≥30). 25 The level of education was classified as: lower education (primary and secondary school), vocational secondary school, higher education (<4 years of university or college education), higher education (≥4 years of university or college education), and other. Participants who identified themselves as nonbinary (n = 6) were included in the descriptive Table 1 but excluded from statistical analysis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, the PREPARED study

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Reporting body weight was optional, resulting in sample variation for BMI categories, †n = 1352 ‡n = 1191.

BMI calculated as kg/m2. Level of education: Lower education (primary school and secondary school).

Differences between gender (women and men) were evaluated using the chi-squared test for independence for categorical variables, and independent samples t-tests and Mann–Whitney U-tests for continuous variables, depending on the skewness of the data.

Linear regression analyses were used to assess the association between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and DQS in the preconception sample of young adults in this study. First, a standard linear regression analysis was performed to assess the crude association, followed by a multiple regression analysis to assess the association adjusted for the possible confounding variables: gender, BMI, and educational level. Further, as sensitivity analyses, the multiple regression analysis was repeated after removing four cases with standardized residuals > 3 and subsequently removing 14 cases with extreme BMI values in a separate analysis. The removal of cases did not materially alter the results. An assessment of a possible interaction effect of gender on the association between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and DQS was conducted by running an additional multiple regression analysis with the interaction term DOHaDKNOWLEDGE X gender.

Data processing and analyses were performed using SPSS 25 (IMB Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IMB Corp.).

Results

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the participants included in the PREPARED study. The participants had a mean age of 27 years (ranging from 20 to 35 years), and most were women (88%). A majority had a BMI within the healthy weight range, and about a third of the women and half of the men had overweight, including obesity. Nine percent of the participants had a mother tongue other than Norwegian. Most participants had higher education (77% had studied at university or university college), but a higher proportion of lower educational level was observed for men.

Participant relationship status was distributed as follows: 42% single, 18% in a relationship (not cohabiting or married), 39% cohabiting or married, and 1% divorced or separated, widow or widower, or other. The proportion of singles were 15% higher among men compared to women.

DOHaDKNOWLEDGE

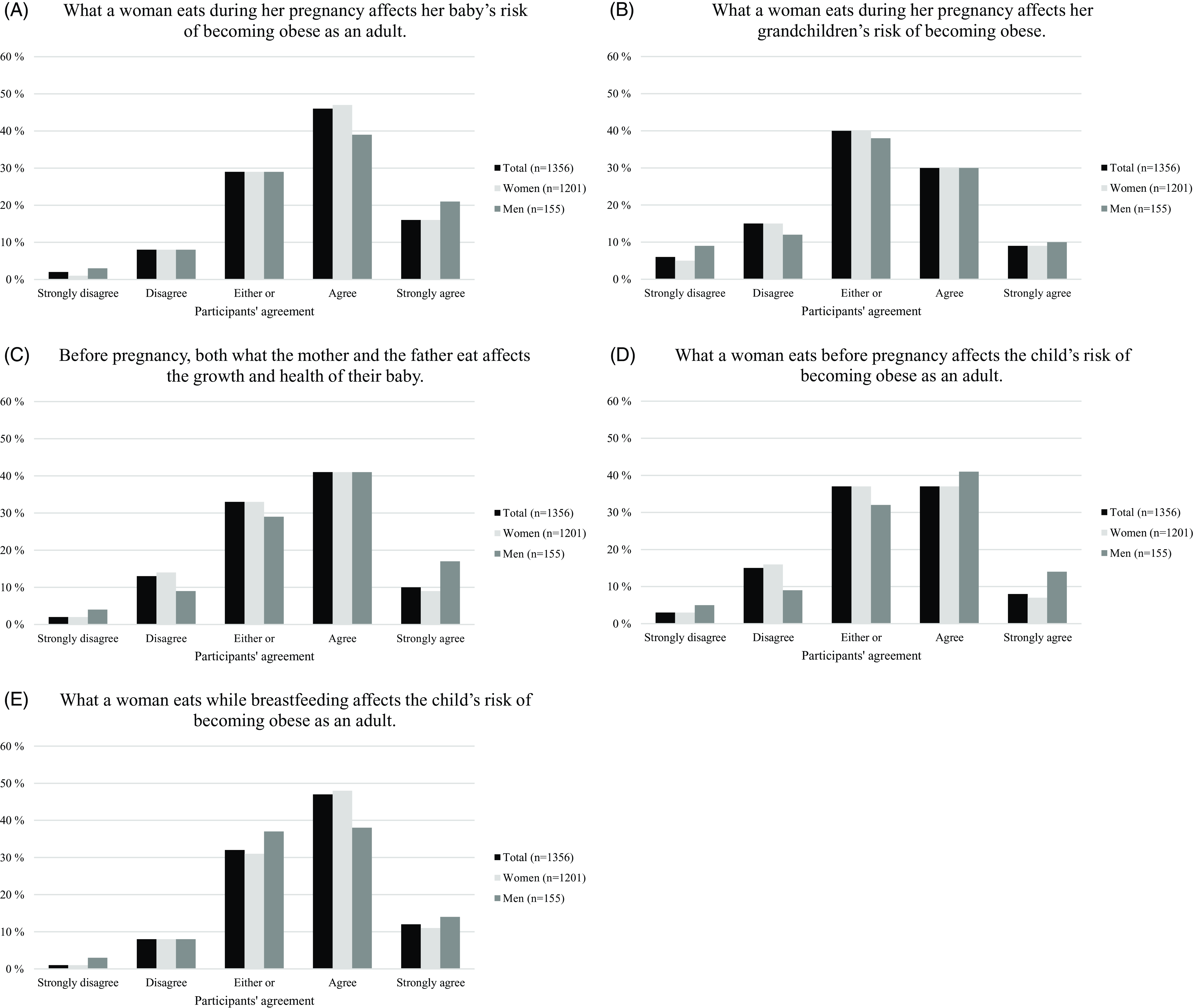

Figure 2 presents participants’ agreement with the five DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements, with the highest proportions of participants reporting “Either or” or “Agree” for all statements. This was corroborated by the mean total DOHaDKNOWLEDGE score of 12 (SD 3.7) points, indicating a moderate knowledge level (table S1). The highest proportion of disagreement (strongly disagree, 6%) was observed for the DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statement pertaining to the association between a woman’s diet during pregnancy and the risk of her grandchildren becoming obese. The two DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements most participants strongly agreed with were the one concerning maternal diet during pregnancy, and the one concerning maternal diet during breastfeeding, and the relation to her baby’s risk of becoming obese as an adult.

Figure 2. Knowledge of the developmental origins of health and disease approach, shown as participants agreement with the five DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements (A–E), presented in percentage, the PREPARED study. Participants identifying as nonbinary (n = 6) were excluded from the total sample.

The total DOHaDKNOWLEDGE score showed similar mean values for women and men (12 (SD 3.6) points and 12 (SD 4.1) points, respectively) (table S1). However, higher proportions of men reported extreme views (strongly disagree and strongly agree) for all the DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements compared to women. Chi-squared tests for independence indicated evidence of associations between gender for the DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements “Before pregnancy, both what the mother and the father eat affects the growth and health of their baby” (p = 0.009) and “What a woman eats before pregnancy affects the child’s risk of becoming obese as an adult” (p = 0.006) (table S1). Little evidence of gender associations was found for the overall DOHaDKNOWLEDGE score or for the remaining statements.

Diet quality

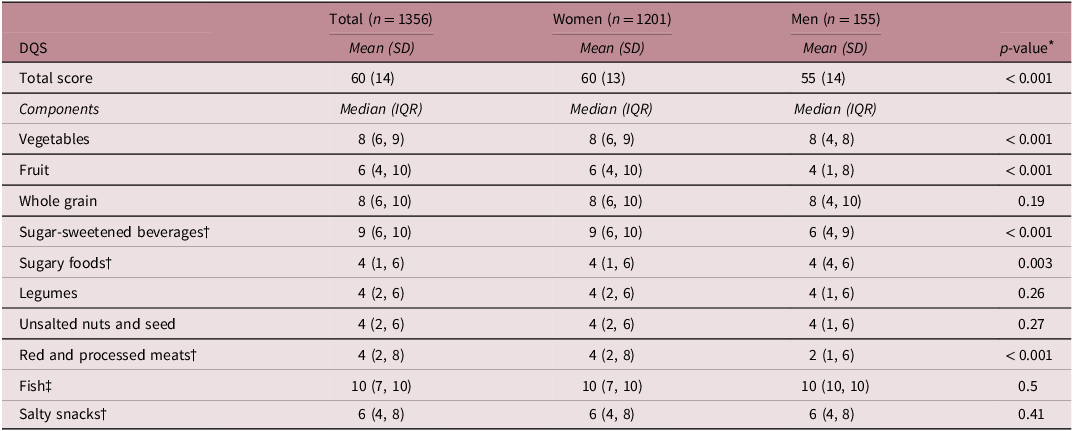

Table 2 shows scores for the total DQS and for the ten individual DQS components. The mean (SD) total DQS was 60 (14), showing a moderate total DQS. Moderately high median DQS were observed for the components vegetables, 8; wholegrain, 8; SSB, 9; and fish, 10. Less-than-optimal DQS were observed for sugary foods, legumes, unsalted nuts and seeds, and red and processed meats (all with a median score of 4 points).

Table 2. The total DQS and the individual DQS components derived from the dietary screener MyFoodMonth 1.1, the PREPARED study

DQS, diet quality score; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Participants identifying as nonbinary (n = 6) were excluded from the total sample. Each diet quality score component scored 0-10 points, resulting in a total score of 0-100 points.

†Component inversely scored, meaning that a higher score reflects a lower intake.

‡Includes fatty fish products, lean fish products, and fish spread.

* Mann–Whitney U-tests except for variable Total score that used independent samples t-test.

Women had a higher mean total DQS than men (mean difference: + 5.45 points; 95% CI: 3.17, 7.72). Gender difference in diet quality favoring women was observed for the DQS components vegetables (p < 0.001) and fruit (p < 0.001), and for the inverted DQS components SSB (p < 0.001) and red and processed meats (p < 0.001). The only gender difference in diet quality favoring men was observed for the inverted DQS component sugary foods (p = 0.003).

A detailed description of aspects of diet quality is available in table S2, which includes all variables from Table 2 (except unsalted nuts and seeds), in addition to alcoholic beverage intake, iodine-rich foods, and calcium-rich foods. Table S2 corroborates the findings in Table 2, showing gender difference for the variables fruits and vegetables (p < 0.001), red and processed meats (p < 0.001), sugary foods (p = 0.004), and SSB (p < 0.001). Moreover, table S2 shows that 14% of participants reported never drinking alcoholic beverages, and 22% reported drinking alcoholic beverages less often than twice a month. Most of the participants reported an intake of iodine-rich and calcium-rich foods ≤ 2.5 times a day (67% and 70%, respectively).

Associations between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and DQS

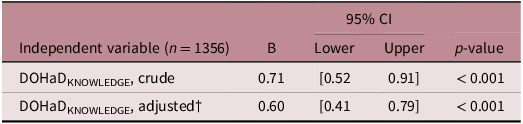

The crude and adjusted associations between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and the total DQS are shown in Table 3. On average, a one-unit higher score on the DOHaDKNOWLEDGE scale was associated with 0.71 point higher total DQS (95% CI: 0.52, 0.91). This was slightly attenuated after adjusting for gender, BMI, and education (0.60 (95% CI: 0.41, 0.79)). No interaction effect of gender on the association between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and total DQS was found.

Table 3. Standard linear regression analysis, crude, and standard multiple regression analysis, adjusted, assessing an association between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and total DQS, the PREPARED study

CI, confidence intervals; DOHaDKNOWLEDGE, developmental origins of health and disease knowledge.

†n = 1346, adjusted for the independent variables: gender; body mass index; education.

Discussion

Most participants agreed, or strongly agreed, with the individual DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements. Higher proportions of men reported extreme views (strongly disagree and strongly agree) than women for all DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements. There was a gender difference in two DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements. The total DQS showed a moderate diet quality among the participants. Women were observed to have a higher total DQS than men. There were gender differences for both the total DQS and the DQS components: vegetables, fruit, SSB, sugary foods, and red and processed meats. Lastly, a positive association was observed between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and total DQS, with little evidence of an interaction effect of gender.

Knowledge of the DOHaD approach – comparison with other studies

To our knowledge, this is one of four studies assessing knowledge of the DOHaD approach in a preconception sample that includes males. Reference Bay, Mora, Sloboda, Morton, Vickers and Gluckman26–Reference Oyamada, Lim, Dixon, Wall and Bay28 Also, there is limited literature published on knowledge of the DOHaD approach in the general population. In a recent study from 2022, Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Lewis, Macciocca and Craig15 assessed public knowledge of epigenetics and epigenetic concepts, that is, how behavioral and environmental factors interact with and cause changes in gene expression, in an Australian adult population (94.6% female, mean age: 37.5 years). Approximately one-third of the sample had heard of DOHaD, but their understanding of the approach appeared low. Another study from 2018, which included first-year undergraduate nutritionist and nursing students in Japan and New Zealand, assessed whether the students had ever heard of DOHaD. The results showed that awareness in both samples was negligible. Reference Oyamada, Lim, Dixon, Wall and Bay28 In a study from 2019, a sample of pregnant Canadian women (mean age: 30.5 years) reported a mean DOHaDKNOWLEDGE score of 9.4 points (SE±0.25). Reference McKerracher, Moffat and Barker17 The present findings of a mean of 12 points (SD 3.7), using the same DOHaDKNOWLEDGE scale, indicate slightly more knowledge of the DOHaD approach in this sample.

The two DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements concerning the effect of maternal diet during pregnancy and while breastfeeding on the child’s risk of adult obesity received the highest support among the participants. One may speculate whether this is due to the fact that pregnant and breastfeeding women in Norway, like many other countries, receive advise from health care personnel regarding the importance of a healthy diet and how to eat healthy during this period of life. 29,30 Although this advice does not necessarily include information regarding the potential risk of the child developing overweight or obesity in the future, the two DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements may be perceived to be in line with the existing diet advice in pregnancy care, compared to the other statements.

Diet quality – comparison with other studies

Substantially more is published on diet quality than on knowledge of the DOHaD approach. Using 2018 data from the Global Dietary Database (GDD), Miller et al. Reference Miller, Webb and Cudhea31 estimated a worldwide mean Alternative Healthy Eating Index (HEI) of 40 (range 0–100), indicating a modest diet quality globally. The study based on the GDD included both men and women, age groups < 1–≥ 95, from 185 countries that covered 99% of the world’s population in 2018. Studies from the UK Reference Winpenny, Greenslade, Corder and van Sluijs32 and the US Reference Lipsky, Nansel and Haynie33 which included samples of adolescents and young adults have also reported a suboptimal diet quality (DASH score: 35/80, and HEI-2010 score: 45/100, respectively). Patetta et al. Reference Patetta, Pedraza and Popkin34 found an overall increase in DQS of 7 points (HEI2015 score: 49 to 56/100) in US young adults between 1989–1991 and 2011–2014. The mean total DQS in the present study of 60/100 points indicates a higher diet quality than for the studies above but is comparable to the findings of Patetta et al. Reference Patetta, Pedraza and Popkin34 from 2011 to 2014. Moreover, our observations of higher DQS among women compared to men are in line with global trends Reference Miller, Webb and Cudhea31 and among UK adolescents and young adults. Reference Winpenny, Greenslade, Corder and van Sluijs32

Looking into the individual DQS components in this study, modest to high scores for fruit (6/10) and vegetables (8/10) were observed, which is better than what other studies have found. Winpenny et al. Reference Winpenny, Greenslade, Corder and van Sluijs32 found that fruit intake was low in both gender and age groups in adolescent and young adults in the UK, and Patetta et al. Reference Patetta, Pedraza and Popkin34 found that vegetable intake decreased between 1989–1991 and 2011–2014. The discrepancies for both total DQS and DQS components fruits and vegetables may possibly be explained by differences in gender balance in the samples (comparative studies ≈ 50% females). Reference Miller, Webb and Cudhea31–Reference Patetta, Pedraza and Popkin34 In addition, people with a higher level of education also have a higher diet quality compared to people with a lower level of education. Reference Miller, Webb and Cudhea31 As the sample in the present study was overrepresented by highly educated participants, this may partly explain the higher total DQS observed in this study compared to other studies, for example, the study by Patetta et al. Reference Patetta, Pedraza and Popkin34 , who report 53% low-income participants in the sample from 2011 to 2014.

There seems to be a J- or U-shaped relationship between diet quality and age, and diet quality has been observed to worsen especially in adolescence. Miller et al. Reference Miller, Webb and Cudhea31 observed this relationship for most regions worldwide, and Lipsky et al. Reference Lipsky, Nansel and Haynie33 as a modest improvement in diet quality during the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. This relationship has also been observed in Norway. In a 1990–2007 study evaluating dietary trajectories in adolescents and young adults, a decrease in consumption of fruits and vegetables was observed from the age of 14 through the early 20s, before improving again toward the age of 30 years. Reference Winpenny, van Sluijs, White, Klepp, Wold and Lien12 SSB and, to a lesser extent, confectionary consumption showed the opposite pattern. The cross-sectional DQS findings in the present study do not reflect the low DQS of about 32/100 observed by Miller et al. Reference Miller, Webb and Cudhea31 for the same age group in high-income countries. Regardless of this discrepancy, the total DQS in this study was still suboptimal, which is strongly in line with all the aforementioned studies.

DOHaDKNOWLEDGE associated with DQS – comparison with other studies

Only one other published study, by McKerracher et al., Reference McKerracher, Moffat and Barker17 has previously evaluated an association between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and diet quality. They found that DOHaDKNOWLEDGE was positively associated with diet quality in a sample of pregnant Canadian women. This study supports their findings, showing a slightly stronger association in this sample of Norwegian preconception women and men, with little evidence of an interaction effect by gender. There is clearly a need to further confirm these findings in other populations in future studies.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. The large sample size gave sufficient precision to our findings. The inclusion of male participants is in line with the relatively new extension of DOHaD, Paternal Origins of Health and Disease (POHaD), Reference Soubry20 and helps filling the research gap which calls for epidemiological studies exploring the influences of the paternal environment on the health of the offspring. Other strengths include the use of a validated dietary screener, shown to satisfactorily rank high and low intakes compared to a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire, Reference Salvesen, Wills, Øverby, Engeset and Medin24 and the use of a DOHaDKNOWLEDGE scale that has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α =.82), indicating that the statements that make up the scale measure the same mental construct. Reference McKerracher, Moffat and Barker17 However, the DOHaDKNOWLEDGE scale has not been validated and has an imbalance of positively and negatively phrased statements, as pointed out by McKerracher et al. Reference McKerracher, Moffat and Barker17 . Moreover, four out of the five DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statements regard the risk of obesity in offspring, and all are directed toward what a woman eats. There is only one DOHaDKNOWLEDGE statement that includes what a man eats and whether it affects the growth and health of the offspring. It is doubtful that this scale adequately measures DOHaD knowledge beyond these aspects. Future studies could benefit from a DOHaDKNOWLEDGE scale that is tailored to a preconception population by including early life exposures and specific nutritional aspects, for example, intake of fruits and vegetables and folic acid supplements.

We believe our results are generalizable to the young adult population in Norway, for the following reasons. First, a relatively large sample with a nationwide sampling method is included. Second, the proportion of overweight, including obese, participants is similar to the proportion of 20–29-year-olds in a large Norwegian cohort, The Trøndelag Health Study (The HUNT Study), Reference Midthjell, Lee and Langhammer35 and third, the study includes participants from both lower and higher education levels. However, the findings are probably most generalizable to women and persons with higher education in the age group. This is supported by data on the level of education for both sexes aged 20-39 from Statistics Norway 36 per 2021, which shows that the sample in this study is underrepresented by participants with lower education (16% vs 56%), and overrepresented for vocational education (7% vs 3%), and higher education (<4 years 39% vs 30%, ≥4 years 38% vs 11%). It is likely that the overrepresentation of selected characteristics may be due to convenience sampling.

This study is not without limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the baseline data used in this study is a major limitation, as we do not know whether the observed improved DOHaDKNOWLEDGE leads to changes in diet, as the exposure (DOHaDKNOWLEDGE) was assessed at the same time as the diet. Second, the dietary data in this study was based on self-reported data and a frequency-based dietary screener. Self-reported dietary assessment methods, and frequency-based questionnaires, have been criticized for a lack of accuracy. Reference Kirkpatrick, Baranowski, Subar, Tooze and Frongillo37 Nevertheless, a dietary screener was considered appropriate to assess the level of detail in dietary intake needed in this study, as the dietary screener has a great advantage by limiting the total burden of data collection imposed on participants. Third, the absence of another indicator of health literacy and pregnancy intention limits the evaluation of the association observed between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and diet quality. The low number of male participants should also be seen as a limitation.

Considering the burden of non-communicable diseases, deteriorating eating habits in adolescents and young adults, and the missed opportunities of preconception health, especially in unintended pregnancies, the importance of DOHaD and early intervention should not be underestimated. Research on how to promote DOHaD knowledge and diet in preconception years is in its infancy. Cost-effective, scalable, individual-level interventions, such as the PREPARED study, Reference Øverby, Medin and Valen23 targeting modifiable nutritional determinants through increased knowledge for informed dietary decisions, have the potential to become impactful digital public health initiatives, if successful. In addition to approaches like the PREPARED intervention, community and policy-level promotion strategies should be evaluated to exploit the opportunity of preconception health. Combining individual- and structural-level strategies to address modifiable determinants of preconception nutrition, as detailed in the Determinants Of Nutrition and Eating framework, Reference Stok, Hoffmann and Volkert38 may lead to synergistic effects.

Conclusions

In this study, a moderate level of both DOHaDKNOWLEDGE (12/20 points) and diet quality (60/100 points) was observed in a sample of preconception Norwegian young adults, with gender differences in diet quality favoring women and DOHaDKNOWLEDGE favoring men. This study indicates that there is a potential to improve DOHaDKNOWLEDGE in young adults and corroborates previous research that shows clear potentials for dietary improvements. A positive association was observed between DOHaDKNOWLEDGE and diet quality, adjusted for sociodemographic factors, with little evidence of an interaction effect by gender. As very little research is done on DOHaDKNOWLEDGE alone or in combination with diet quality, future research is clearly needed to confirm the findings in other populations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2040174423000314.

Acknowledgments

None.

Financial support

This work was supported by the University of Agder.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (the Regional Ethics Committee, REC: 78,104) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the institutional committees (the Norwegian Data Protection Service, NSD: 907212, and our Faculty Ethical Committee, FEC: 20/10119).