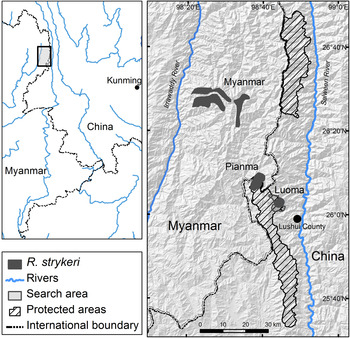

The snub-nosed monkey genus Rhinopithecus was previously thought to comprise four rare, threatened primates (R. avunculus, R. bieti, R. brelichi and R. roxellana), known only from isolated parts of southern China and northern Vietnam (IUCN, 2016). Rhinopithecus strykeri, known as the Myanmar snub-nosed monkey, or Nujiang snub-nosed monkey in China, was discovered in 2010 in forests above 1,720 m altitude in Kachin state, north-east Myanmar (Geissmann et al., Reference Geissmann, Lwin, Aung, Aung, Aung and Hla2011). A second population was discovered the following year in Pianma on the western slopes of Gaoligong Mountains, in Yunnan, China (Fig. 1; Long et al., Reference Long, Momberg, Ma, Wang, Luo and Li2012). Rhinopithecus strykeri primarily inhabits mid-montane moist evergreen broad-leaved forest and coniferous broad-leaved mixed forest (Geissmann et al., Reference Geissmann, Lwin, Aung, Aung, Aung and Hla2011; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiang, Wang, Xiao, Xiao and Ren2015). Genetic evidence indicates that it separated from the R. bieti clade in the Late Pleistocene, c. 0.24 million years ago (Liedigk et al., Reference Liedigk, Yang, Jablonski, Momberg, Geissmann and Lwin2012) when two major barriers, the Mekong and the Salween Rivers, may have physically isolated segments of the parent population. All species of snub-nosed monkeys are reported to live in a multilevel or modular society, composed of several one-male harem breeding units that travel together to form a band, and one or more all-male units that follow the band (Kirkpatrick & Grueter, Reference Kirkpatrick and Grueter2010).

Fig. 1 Locations of the known populations of Rhinopithecus strykeri in the Sino-Myanmar border region.

Interviews (Geissmann et al., Reference Geissmann, Lwin, Aung, Aung, Aung and Hla2011; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Huang, Zhao, Zhang, Sun and Matthew2014) suggested there may be up to 14 groups of Myanmar snub-nosed monkeys, with a total population of < 950 individuals, in four separate areas close to the Sino-Myanmar border: one in Pianma, China, and three in Myanmar. In China field observations of R. strykeri in Pianma have been conducted since 2011 (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiang, Wang, Xiao, Xiao and Ren2015), although limited behavioural data have been collected because of the rugged terrain and long rainy season from April to October. This group, with > 100 individuals, lives at 2,400–3,300 m and has an estimated home range of 22.9 km2 (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiang, Wang, Xiao, Xiao and Ren2015).

Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Huang, Zhao, Zhang, Sun and Matthew2014) predicted the species would also occur on the eastern slope of the Gaoligong Mountains, in China, where we searched during October 2013–September 2015 (see search area in Fig. 1). One or two researchers, with two field guides, searched for the species using outline transects (Plumptre et al., Reference Plumptre, Sterling, Buckland, Sterling, Bynum and Blair2013) along each sub-ridge, during 08.00–19.00, 1–3 weeks per month depending on weather. We located the species, and took > 200 photographs and 27 videos (Plate 1). We also found evidence of chewed branches and faeces consistent with those collected from the species at other sites.

Plate 1 Mother and infant of Rhinopithecus strykeri in the newly discovered population in Luoma, China, near the border with Myanmar (Fig. 1).

In addition, we set up 19 camera traps (Acorn Ltl-6210 MC, Shenzhen Ltl Acorn Electronics, China) during April–September 2015, on wildlife trails and in five food trees, at a height of 15–20 m. The trees were three toufucha Gamblea ciliata and two shanxiangguo Dodecadenia grandiflora, which were identified by our local guides as feeding trees for the species. We obtained 54 successive infrared camera-trap photographs of the species in one event. The camera trap was in one of the toufucha tree crowns.

We collected faeces on 5 May 2015, at 3,180 m, and confirmed they were the faeces of Myanmar snub-nosed monkeys based upon their shape, size and contents, which included the remains of leaves and conifer needles. At 19.00 on 16 September 2015 we observed Myanmar snub-nosed monkeys fighting and vocalizing loudly in a patch of hemlock Tsuga dumosa–bamboo–rhododendron forest; they then moved to a sleeping site on the ridge of the mountain at about 19.30. The next day we followed them during 7.00–16.30. We ceased to follow the group thereafter because of heavy rain and dense fog. We had followed the group for approximately 9½ hours, at a mean travel speed of 168.2 m per hour. Assuming that the group would have continued travelling and foraging for at least another 2½ hours, we estimate the snub-nosed monkeys would have travelled c. 2,018 m on that day.

To estimate group size we reviewed the 4 infrared photographs, identifying 18 adult or subadult monkeys, with 10 appearing in photographs during 17.53–17.58 and eight in photographs during 18.06–18.10. The mean passing rate of snub-nosed monkeys was 2.3 individuals per minute. Given that several distinguishable adult males appeared in these photographs, and none of the monkeys were carrying infants, we assume these individuals were members of an all-male unit. In addition, on one occasion we observed c. 20 infant and juvenile monkeys. Given the sex-age ratios of males to females (1:2.1), females to infants (4.7:1), and adults to immatures (2.5:1) in the Pianma R. strykeri population (Li et al., Reference Li, Chen, Sun, Wang, Huang and Li2014), we tentatively estimate that this population comprises > 70 individuals.

The Luoma population lies c. 14 km in a straight line south-east of the Pianma population reported by Long et al. (Reference Long, Momberg, Ma, Wang, Luo and Li2012) and 80 km south-east of the Myanmar site reported by Geissmann et al. (Reference Geissmann, Lwin, Aung, Aung, Aung and Hla2011). The Luoma population lives in the core zone of the Gaoligong Mountain National Nature Reserve, 1 day's walk from the nearest village. The forests are mostly mixed broad-leaf–hemlock forest or hemlock–rhododendron forest at 2,600–3,300 m, and are mostly pristine, with little anthropogenic disturbance. Compared to the declining populations in Myanmar (c. 300 individuals; Geissmann et al., Reference Geissmann, Lwin, Aung, Aung, Aung and Hla2011) and Pianma (c. 100 individuals; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiang, Wang, Xiao, Xiao and Ren2015), which have suffered from the threat of hunting and habitat degradation (Geissmann et al., Reference Geissmann, Lwin, Aung, Aung, Aung and Hla2011; Yin Yang, pers. obs.), the Luoma population may have potential to be a source population for the formation of new additional R. strykeri populations, and therefore requires strict and effective conservation management.

Additionally, living in forests dominated by hemlock, the ecology of the Luoma population may differ from that of the other populations, which inhabit moist evergreen broad-leaved forests. Based on 358 interviews with local people in the region, individuals of this population may travel to forests outside the Reserve, close to Chengan township, where they may occasionally be hunted by the Lisu people (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Huang, Zhao, Zhang, Sun and Matthew2014). The border of the reserve may therefore need to be adjusted to ensure the full protection of the population. We aim to conduct further research and to develop a conservation action plan to protect nearby forests, which also harbour other threatened species, such as the Endangered red panda Ailurus fulgens styani, Vulnerable Mishmi takin Budorcas taxicolor taxicolor, and Vulnerable Sclater's monal Lophophorus sclateri. In addition, further surveys to locate other potential R. strykeri populations and to determine accurately the population size in the Sino-Myanmar region are required for a full assessment of the conservation status and needs of this Critically Endangered primate.

Acknowledgements

This research complied with the regulations governing primate research in China, and the policies and guidelines of the Australian National University and Dali University for the ethical treatment of primates. We thank the Nujiang Forestry Department and the Gaoligong Mountain Nature Reserve for their support during our surveys. Our field guides, Afenghua and Kenhuaniuba, contributed to this study. Paul A. Garber, Colin Groves, Guy Michael Williams and two anonymous reviewers provided valuable suggestions and helped with English. This research was funded by the National Science Foundation of China (31260149, 31260145, 31670397) and Zoological Society for the Conservation of Species and Populations (Germany; 7.Rhinopithecus.MMR.2015), and also supported by the Collaborative Innovation Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation in the Three Parallel Rivers Region of China and Key Lab of Yunnan Education Department in Erhai Catchment Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Development.

Author contributions

YY, Y-CL and WX conceived the research. C-XH, BW and G-SL facilitated the field work. YY, Y-PT, C-XH, ZH, S-HD, BW and G-SL led the long-term field research. YY, Y-PT, ZH and S-HD performed the analyses and mapping. YY wrote the article with input from Y-CL, Z-FX and WX.

Biographical sketches

Yin Yang is studying the behaviour and conservation biology of R. strykeri in the Gaoligong Mountains National Nature Reserve in China. Ying-Ping Tian is a park ranger committed to the conservation of R. strykeri. Chen-Xiang He, Bin Wang and Guan-Song Li are governors of the reserve and initiated the conservation programme for R. strykeri in China. Shao-Hua Dong has coordinated field surveys for R. strykeri. Zhipang Huang’s research interests include conservation biology and the behavioural ecology of primates. Zuo-Fu Xiang specializes in the conservation biology, behaviour and cognitive science of primates. Yong-Cheng Long is a primatologist with a lifelong interest in snub-nosed monkeys. Wen Xiao has a wide range of research interests in conservation biology, behavioural ecology and wildlife–habitat relationships, especially of primates.