A basic premise of international relations (IR) is that material power affords security. As Waltz explains, “The more powerful enjoy wider margins of safety … The weak lead perilous lives.”Footnote 1 Mearsheimer pushes further: “The best guarantee of survival is to be a hegemon, because no other state can seriously threaten such a mighty power.”Footnote 2 When the material balance fails to explain threat perception, canonical IR theory incorporates additional factors—like mutual interests and shared identity—rather than question the premise itself.Footnote 3 Beyond theory, this premise guides foreign policy practice. US elites today instinctively respond to China's growing international prominence with further accumulation of US power.Footnote 4

Guided by advances in psychological research on power, I show that this premise is mistaken: the sense of power inflates threat perception in IR. The sense of power, which derives from asymmetric control over resources, activates human “approach” tendencies, the motivational engine of psychology.Footnote 5 Among other effects, the sense of power activates intuitive thinking, including a reliance on gut feelings, affective states, and cognitive shortcuts like heuristics and prior beliefs. A sense of power directs attention to the self, privileging one's own “instincts” in the decision-making process. In contrast, a sense of weakness directs attention to others, prompting awareness of varied information and more deliberate processing of that information. In short, “power changes people.”Footnote 6

Adapting this interpersonal research to an international setting, I show that the sense of relative state power also activates intuitive thinking, which inflates threat perception in the context of IR. Behavioral IR scholars have long suggested that intuitive thinking inflates threat assessments beyond rationalist and realist expectations.Footnote 7 In fact, most psychological mechanisms known to inflate threat perception in IR are intuitive in nature, including the emotions of anger and panic, prior beliefs about hostile intentions, biases like the fundamental attribution error, and stereotypical enemy images.Footnote 8 We have missed that the sense of power activates a reliance on this less reflective, more intuitive cognition.

Three forms of evidence support this expectation. First, survey experiments fielded in China and the US show that respondents assigned to lead a hypothetically powerful country view a proliferating neighbor as more threatening than respondents assigned to lead a weaker country. The China survey finds that the power treatment amplifies the effect of prior beliefs about aggressive intentions, a hallmark mechanism of intuitive thinking. The US survey examines the mediation process more directly: power activates intuitive thinking, like loss aversion and perceived urgency of the situation, which explains threat inflation. A supplementary experiment further establishes the effect of intuition on threat inflation via time pressure, adding strong experimental support for the argument.Footnote 9

Second, a reanalysis of a 2020 survey of Russian elites reveals the same pattern of results.Footnote 10 Russian elites who feel that Russian power is on the rise are more likely to perceive the US, Ukraine, and NATO as threatening. This analysis examines competing explanations, like interest expansion and prior military experience. Compared to these competing explanations, the sense of Russian power is a more consistent predictor of elite threat perception. Supplementary experimental evidence from the US confirms that rising power increases threat perception relative to declining power.Footnote 11 These results extend the paper's expectations to a dynamic setting: the effect of power on threat perception is substantively identical across dynamic and static power comparisons.

Finally, a text analysis of all available Cold War documents in the Foreign Relations of the United States shows that the sense of US power explains positive variance in perceptions of threat from the Soviet Union, China, and the Viet Cong. This foreign policy decision making takes place behind closed doors, offering external validity beyond survey methods. The analysis further verifies the mechanism. The sense of power correlates with terms that proxy for intuitive thinking, and these terms explain the association between power and threat perception. Supplementary dynamic analyses show that these textual results hold for the sense of rising US power.Footnote 12 Power increases threat perception across static and dynamic settings, and across national and cultural contexts. While I focus on elite decision makers as the unit of analysis, the findings are substantively identical across elite and public samples.Footnote 13 I find no evidence that the sense of power decreases threat perception.

Along the way, I follow conventional IR theory in definitions of key terms. Power refers to relative material capabilities, notably military and economic capacity.Footnote 14 The sense of power is the feeling of control and influence that flows from those capabilities. Threat perception refers to the subjective assessment of others’ capability and intent to do harm.Footnote 15 Rather than redefine these terms, I simply show that relative capabilities impart a feeling of power, which inflates threat perception relative to conventional IR expectations.

The paper's contributions are twofold. First, power is a feeling that changes individuals in a “first image reversed” fashion.Footnote 16 Psychological IR typically conceptualizes power as a material and structural baseline, rather than a cause of psychology itself.Footnote 17 Yet, in our daily lives, adages like “power corrupts” capture the commonsensical notion that power is a feeling and experience that changes the wielder. I find that power changes wielders in consequential ways: power explains differences in psychological mechanisms central to behavioral IR research.Footnote 18 Just as Gourevitch shows that structure changes states in a “second image reversed” fashion, I show that structure—namely the balance of power—changes individuals in a first image reversed fashion.Footnote 19

Second, beyond behavioral IR, the results reveal a basic tension in IR theory. IR scholars typically assume that material power increases state security. I show that the feeling of power that flows from those capabilities makes individuals feel less secure. Perhaps smaller states underbalanceFootnote 20 because their leaders do not see the world as very dangerous. Powerful states might overreact and overextendFootnote 21 because their leaders see threats everywhere. Most controversially, perhaps the leaders of rising states, not declining states, feel more threatened.Footnote 22

These findings help explain puzzling foreign policy practice. Recent research reveals that over 25 percent of all US military interventions in the US's history took place in the post–Cold War era, a period in which preponderant US power should have made US leaders feel safer.Footnote 23 IR scholars often explain such behavior through the proposition that “the powerful can”—they enjoy a permissive international environment.Footnote 24 I show empirically that this is only part of the story. We have missed that the feeling of power attunes individuals to threats. The paper's concluding section discusses implications for contemporary US–China relations. The flawed premise that power makes us feel safer currently informs crucial foreign policy decisions in Washington and Beijing.

It's Good to Be King: Power and Threat Perception in International Relations

IR scholarship traditionally defines threat as a combination of capability and hostile intent.Footnote 25 All else equal, stronger states are more dangerous than weaker states, and hostile intentions are more threatening than benign intentions. While many frameworks include additional variables, like cultural and identity factors, I focus on a narrower question: the effect of power on threat perception.Footnote 26

This definition of threat implies that material strength should increase security relative to material weakness. In realist and rationalist scholarship, states solve security dilemmas, balance threats, and fend off rising states through the accumulation of military and economic power.Footnote 27 The stronger you are, the safer you should be.

Surprisingly, behavioral IR has yet to seriously examine the effects of power on threat perception, an oversight given that threat perception is ultimately “between the ears.” How does power affect the subjective sense of security? Rousseau and Garcia-Retamero randomly assign information about military strength, and find that the stronger perceive less military threat.Footnote 28 But Tomz and Weeks find a null effect of the military balance on support for aggression.Footnote 29 Similarly, Tingley finds mixed effects of rising versus declining power on threat perception, but the experiments were designed to examine commitment problems rather than threat perception per se.Footnote 30

There is a reason for the paucity of behavioral research on power. Neorealism stripped human nature from questions of power, reducing power to a phenomenon measured with indicators like steel production and population size. Prior to neorealism's ascendance, classical realists agreed that material capabilities matter. Morgenthau held that armed strength is the “most important material factor making for the political power of a nation.”Footnote 31 But, in contrast to neorealism, classical realist accounts turned firmly on a sensitivity to human nature. “Political power is a psychological relation between those who exercise it and those over whom it is exercised,” argued Morgenthau.Footnote 32 For Spykman, “a balance of power in which the weights are equal gives no sense of security; it contains no margin of safety.”Footnote 33 Citing the success of the Locarno Treaty as an ideal-typical case of power politics, Carr writes that “it was the psychological moment when French fear of Germany was about equally balanced by Germany's fear of France.”Footnote 34 Writing later, Gilpin argued that “most important of all, hegemonic wars are preceded by an important psychological change in the temporal outlook of peoples.”Footnote 35

This sensitivity to the first image laid the groundwork for a controversial and largely forgotten proposition: power might exert no effect on felt security and might even heighten awareness of threats. Wolfers was most explicit: “Security in the subjective sense [is] not proportionate to the relative power position of a nation. Why, otherwise, would some weak and exposed nations consider themselves more secure today than does the United States?”Footnote 36 Wolfers goes on to speculate: “Probably national efforts to achieve greater security would also prove, in part at least, to be a function of the power and opportunity that nations possess to reduce danger through their own efforts.”Footnote 37 That is, if leaders feel able to address threats, they might see more threats. The point is simple but contrasts with what has become established IR wisdom about the relationship between strength and threat perception.

Only with the US's unipolar moment has this possibility received renewed attention. Jervis observes that “increased power brings with it new fears. As major threats disappear, people elevate ones that previously were seen as quite manageable.”Footnote 38 Kagan concurs: “Americans are quicker to acknowledge the existence of threats, even to perceive them where others may not see any, because they can conceive of doing something to meet those threats.”Footnote 39 And, using some of the same psychological work that I adapt to IR, Fettweis provides an important first take on how power affected US leaders’ post–Cold War threat assessments.Footnote 40

To explain these theoretical deviations, scholars typically argue that individual or domestic factors—like President Bush's prior beliefs or domestic interest groups—inflate threat perception beyond that warranted by the strategic balance.Footnote 41 Another common explanation is a permissive international environment. The powerful might focus on threats due to opportunity, not fear, simply because “they can.” While all of these factors are likely part of the story, I offer a very different explanation: at the individual level, we are simply wrong about the relationship between power and threat perception. The next section describes emerging psychological research that speaks to this issue.

Uneasy Lies the Head: Advances in the Psychology of Power

Since the early 2000s, there has been a rapid growth in psychological work on power. However, this literature remains largely unexplored in behavioral IR. Like much of IR theory, psychologists conceptualize power as “asymmetric control over valued resources in social relations.”Footnote 42 For example, the CEO of a corporation has control over subordinates’ salaries and influence over the strategic direction of the company. In IR, power most traditionally derives from relative military and economic capabilities, resources that beget influence on the world stage.Footnote 43

In contrast to IR theory, psychologists show that objective power activates a subjective sense of power, the feeling that one can control or influence the experiences, behaviors, and outcomes of others.Footnote 44 It is the difference between a phlegmatic awareness of capacity and the feeling of control and influence that flows from that capacity. While individuals rely on perceptions to form these relative power assessments, as neoclassical realists suggest,Footnote 45 the sense of power pushes further to reveal that strength and weakness activate different psychological properties.

The “approach–inhibition” theory of power represents the dominant paradigm of socio-cognitive research on power.Footnote 46 Most of human thought and behavior can be categorized into “approach” versus “avoidance,” two basic evolutionary impulses that facilitate thriving and surviving.Footnote 47 The core expectations of approach–inhibition theory are that power activates approach tendencies, and the lack of power activates inhibited tendencies.

In the psychological domain of approach, “the traffic lights are always green.”Footnote 48 Self-focused and self-interested, such individuals display assertive behaviors, deficits in empathy, and a reliance on cognitive shortcuts like heuristics and stereotypes. In contrast, an inhibited orientation is meek and avoidant, more empathetic, and more attentive to external information. For the former, think high-level company executive; for the latter, an employee reporting to that executive.Footnote 49

Psychologists study the sense of power experimentally and correlationally. Experimental methods often use objective power differences to prime the sense of power or weakness. Correlational studies often use survey items like “I have a great deal of power” or “I can get others to do what I want” to directly measure the sense of power.Footnote 50 Again, these are not competing definitions of power. Power refers to control over resources. The sense of power is the feeling of control and influence that flows from those resources. A notable empirical takeaway is the consistency of results across correlational and experimental methods, as well as in samples that range from students to elite decision makers.Footnote 51

Finally, psychologists of power conceive of power's effects in two primary ways. First, the sense of power changes individuals in predictable ways. For example, it tends to activate distrust of others’ intentions,Footnote 52 an average treatment effect regardless of individual differences. Second, it reveals individuals, amplifying their underlying dispositions and traits. For example, individuals prone to distrusting others might become even more suspicious with power. This typically takes the form of interactions between power treatments and individual differences. Thus the sense of power both changes and reveals.

The Sense of Power Activates Intuitive Thinking

A key finding from this research is that power activates intuitive thinking in the decision-making process, including a reliance on gut feelings, affective states, and cognitive shortcuts like heuristics and prior beliefs.Footnote 53 Susan Fiske pioneered the insight that powerful individuals are more likely to stereotype others.Footnote 54 Fiske's intuition was that bosses know less about their subordinates than vice versa. The less powerful attend more closely to information about powerful individuals, because “people pay attention to those who control their outcomes.”Footnote 55

Keltner, Gruenfeld, and Anderson gave this insight a cognitive kick, linking power and weakness to the approach and avoidance systems, respectively.Footnote 56 They grafted their expectations onto a “dual-process” model of cognition, hypothesizing that power and weakness activate relatively automatic and controlled thinking, respectively.Footnote 57 This provided further theoretical reason to believe that the sense of power increases a reliance on intuition over external information in the decision-making process. Indeed, early theorists of the approach system equated “approach” with “impulsivity” and other automatic cognitive processes.Footnote 58

Subsequent research in the approach–inhibition tradition, which motivates my argument, often retains the approach system from Keltner, Gruenfeld, and Anderson as the cognitive engine but emphasizes Fiske's attentional aspects that drive intuitive thinking,Footnote 59 rather than automaticity per se. The idea is that, because the powerful feel autonomous of others, they do not need to pay close attention to others. They can simply rely on gut instincts, heuristics, and stereotypes to get by. This has certain advantages, like more efficient decision making. But psychologists of power also show that these mechanisms can have detrimental effects, like a reliance on negative stereotypes, implicit bias and prejudice, reduced empathy, and dehumanization of others.Footnote 60 In short, the powerful think from the gut.

The expectation that power increases a reliance on intuition is compatible with two leading paradigms in psychological IR research, as Pauly and McDermott describe.Footnote 61 One paradigm emphasizes the emotional basis of reason,Footnote 62 and is perhaps most associated with Antonio Damasio's somatic marker hypothesis. As Bechara and Damasio explain, “The somatic marker hypothesis provides neurobiological evidence in support of the notion that people often make judgments based on ‘hunches,’ ‘gut feelings,’ and subjective evaluation of the consequences.”Footnote 63 Somatic predictions also overlap with what Verweij and Damasio refer to as Gigerenzer's “gut feeling” model.Footnote 64 In IR, influential work by scholars like Rose McDermott and Jonathan Mercer emphasizes the primacy of emotion in downstream cognition, calling into question the conceptual distinction between emotion and reason.Footnote 65

The second paradigm, as Pauly and McDermott describe,Footnote 66 is a dual-process perspective popularized by Kahneman.Footnote 67 This perspective categorizes emotion, heuristics, and intuition under the umbrella term of “system 1” thinking. Dispassionate, effortful, and deliberate thinking fall under the umbrella term of “system 2.” According to this account, humans are usually guided by system 1 intuitions, which are only occasionally checked by more procedurally rational system 2 processes. This paradigm undergirds many of the contributions in IO's special issue on the behavioral revolution,Footnote 68 as well as a host of other influential psychological IR work.Footnote 69 Although the distinction between system 1 and system 2 is conceptually parsimonious, some work, notably from state-of-the-art neuroscience research, finds it simplistic.Footnote 70

Importantly, psychology of power research on intuition is compatible with both of these leading paradigms. In a Damasio framework, the powerful privilege their intuitions in the decision-making process, and when higher-order thinking is recruited, this downstream reasoning is shaped by initial affective responses in an interdependent fashion. In a dual-process framework, the powerful rely more heavily on intuition (system 1) and are less likely to use more deliberate (system 2) thinking to check these system 1 impulses. Whereas Keltner, Gruenfeld, and Anderson used a dual-process understanding of automatic versus controlled cognition,Footnote 71 much subsequent psychology of power research adopts a perspective more consistent with Damasio: emotion is primary and influences downstream cognition.Footnote 72 All come to the same conclusion: in making decisions, the powerful rely more heavily on their intuitions than on external information. Or, as George W. Bush put it, “I don't spend a lot of time taking polls around the world … I just got to know how I feel.”Footnote 73

Intuitive thinking likely helps explain the psychological finding that power activates distrust of others’ intentions, a key component of threat perception in IR. Invoking insights from Hans Morgenthau, Inesi, Gruenfeld, and Anderson show that the random assignment of power increases distrust of others, and argue that “power may be inextricably tied to anxieties about the meaning of social interactions and others’ intentions.”Footnote 74 Similarly, Foulk and colleagues show that the sense of power activates negative evaluations of others’ intentions, notably perceived incivility in the workplace.Footnote 75 While these findings contrast with Keltner, Gruenfeld, and Anderson's initial expectation that power decreases threat perception,Footnote 76 they align with the attentional argument that power leads to simplified, often negative, images of others.Footnote 77

Beyond distrust of others’ intentions, the sense of power activates deterrent reactions, a defensive behavioral response. Across nine studies, Mooijman and colleagues show that power increases distrust of others, which “increases both the reliance on deterrence as a punishment motive and the implementation of punishments aimed at deterrence.”Footnote 78 These defensive responses suggest that the sense of power increases awareness of threats. Thus, as Mooijman and coauthors point out, power activates a Hobbesian state of mind, marked by generalized suspicion of others and a reliance on deterrence to fend off those perceived threats.Footnote 79 The intuition behind these studies is that “it is not uncommon for high power members, like the CEOs of top management teams, to be suspicious, distrusting, and worried that other team members are plotting against him or her.”Footnote 80 In other words, uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.

However, these interpersonal studies provide only suggestive evidence that power might increase threat perception in an intergroup domain like IR. Would this research travel to IR? The competitive intergroup dynamics that often mark international security likely amplify these effects. As Dépret and Fiske write, “Intergroup interactions inherently carry a more negative and competitive interdependence structure than interpersonal interactions.”Footnote 81 Intergroup threat theorists concur: “relations between groups are far more likely to be antagonistic than complementary.”Footnote 82 Thus, to the extent that leaders display pessimism about others’ intentions in IR, the sense of power would further amplify this pessimism. The next section adapts these insights to an IR context before examining these expectations.

Implications for Threat Perception in World Politics

Psychological research on power suggests a straightforward implication for IR. The sense of state power—the feeling that “our state” has a power advantage relative to “your state”—activates a reliance on intuitive thinking. In turn, canonical IR scholarship shows that intuitive thinking in the threat assessment process, such as a reliance on heuristics and prior beliefs, tends to inflate threat perception relative to standard IR expectations.

By “the sense of state power,” I mean the feeling of control and influence that flows from perceptions of a power advantage. This advantage could derive from static or dynamic comparisons, as realists and rationalists maintain. The former is a relatively stable sense of power “today,” such as the fixed p term in Fearon's discussion of the information problem.Footnote 83 The latter is a sense of increasing power relative to another state, such as the shifting p term in Fearon's discussion of the commitment problem.Footnote 84 In psychological theory, all that matters is that decision makers believe their state has a power advantage, however subjectively defined.

In turn, I expect the sense of power to activate a greater reliance on intuitive thinking mechanisms known to inflate threat perception in IR. Consider just a few of these. The fundamental attribution error refers to the overweighting of dispositional factors (as in, the Soviets have “evil” intentions) and the discounting of situational factors (as in, the Soviets need armaments for their own security). Power increases a reliance on such cognitive shortcuts, which often inflate threat perception.Footnote 85 Similarly, stereotypical images and prior beliefs about hostile intentions tend to anchor and inflate threat assessments.Footnote 86 George H.W. Bush's reference to Saddam as “another Hitler” is an example of simplified, stereotypical thinking resistant to disconfirming evidence.Footnote 87 Power activates a reliance on negative stereotypes and prior beliefs.

Beyond these cognitive shortcuts are the emotions that underpin threat perception, which are also intuitive in nature. As Stein puts it, emotions “constitute a primary influence in automatic threat detection and the bias is in favor of overdetection rather than underestimation.”Footnote 88 For example, Mercer shows that the Truman administration's panicked reaction to North Korea's invasion of South Korea inflated assessments of Stalin's hostile intentions beyond the peninsula.Footnote 89 In making decisions, the powerful rely more heavily on their emotions, and especially “approach” emotions like anger. Finally, deficits in empathy and perspective-taking are common barriers to revision of threat assessments.Footnote 90 Power activates both of these effects, as well as the tendency to dehumanize others.Footnote 91 These effects ease the psychological constraints on doing harm to others.

By contrast, as psychologists of power have shown, the sense of weakness activates more deliberate thinking about others. Translated to IR, because the outcomes of weaker states are more dependent on more powerful actors, the sense of weakness should activate an openness to incoming information, intentionality in the processing of that information, and a greater willingness to update prior beliefs in accordance with that information. Decision makers in weaker states also perceive threat. But they arrive at these assessments in ways that better approximate the dispassionate and procedurally rational accounting envisioned by security scholars.Footnote 92 That is, the weak are less likely to inflate threat. While all individuals think intuitively to some degree, we can explain variance in this tendency according to the sense of power and weakness.

This is not to imply that intuitive mechanisms generate “irrational” assessments of threat. Using the fundamental attribution error as an example, Johnson argues that threat inflation is likely evolutionarily adaptive, encouraging us to “err on the side of caution when dealing with other actors and states.”Footnote 93 Therefore, I use the term “inflation” relative to standard IR expectations, not as a subjective claim that this kind of decision making is “worse.” The latter is a political question.

The relevant level of analysis is the individual decision maker. Decision makers ultimately perceive power and threat. However, given the translation from an interpersonal to an interstate setting, it is important to describe the state-level dimension of the argument. Following Renshon's logic,Footnote 94 power (like status) is a relative state phenomenon, but decision makers also feel and experience their state's power. Because decision makers identify with the state, “group phenomena are felt and can be analyzed at the individual level.”Footnote 95 Further, Kahneman and Renshon find that intuitive mechanisms increase hawkishness.Footnote 96 Kertzer and colleagues show that hawkish biases persist in group settings.Footnote 97 Therefore, while I avoid strong state-level claims, there is little reason to expect these effects to “wash out” at the state level.

My theory concretizes intuitions that IR scholars have long held but lacked precise terms to express. When Jervis observes that “increased power brings with it new fears,” he intuits that the balance of power shapes leaders in a first image reversed fashion.Footnote 98 In Jervis's observation, power does the causal work, not individual differences. Further, in a response to Kahneman and Renshon,Footnote 99 Mueller adds the hawkish bias of “overestimating the threat posed by weak enemies.”Footnote 100 Kahneman and Renshon respond that “we do not have a psychological account of this observation,” speculatively connecting this phenomenon to the availability bias. I believe Kahneman and Renshon are correct that cognitive shortcuts often inflate threat. But I go further to suggest that decision makers overestimate threats posed by the weak precisely because they feel stronger than the weak.

Face-level evidence is widespread. Consider Cold War US elites. While superpower competition certainly injected structural insecurity, classic examples of US threat inflation often centered on far weaker states. US decision makers feared that the “loss of any single country” in Southeast Asia would “endanger the stability and security of Europe.”Footnote 101 President Lyndon Johnson warned that communists would “chase you right into your own kitchen.”Footnote 102 Indeed, the psychologist Roderick Kramer directly links Johnson's power to paranoia regarding Vietnam.Footnote 103 Johnson became convinced that malevolent “others”—from Martin Luther King Jr. at home to a communist conspiracy abroad—were plotting to subvert his success in Vietnam, and berated his CIA director for failing to find evidence for this belief.

The rest of the paper tests these expectations. Both between-state and within-state comparisons are relevant. I first use experiments to make between-state comparisons, testing the notion that decision makers of stronger states are more likely to inflate threats than decision makers of weaker states. However, because perceptions vary among decision makers, there is often analytically important within-state variation in such assessments. Wohlforth shows, for example, that European decision makers in the same state arrived at different assessments of their state's capabilities before World War I.Footnote 104 Therefore, I then turn to a survey of Russian elites and a text analysis of US decision making during the Cold War. This approach holds the within-state decision-making setting constant to examine the unique role of varying perceptions.Footnote 105

Cross-National Survey Evidence: Macrofoundations for Threat Perception

This section turns to the measurement precision afforded by surveys. First, experiments fielded on convenience samples in China and the US show that power increases threat perception. Because many variables vary alongside power in a state's threat environment, experiments offer tight control over the objective level of external threat. Second, a reanalysis of a 2020 survey of Russian elites suggests that the sense of Russian power correlates positively with a range of security threats, extending the experimental results to actual elites in IR. These surveys provide evidence from three different great powers, where the stakes are consequential.

Experimental Evidence from China

The first survey experiment was fielded by Qualtrics on a sample of 880 Beijing adults in July 2021.Footnote 106 The survey presented respondents with the following, amended from previous experimental IR work on nuclear proliferation: “Please take a moment to imagine that you are the leader of your own hypothetical country (‘Country A’). Your neighboring country (‘Country B’) is developing nuclear weapons and will have its first nuclear bomb within six months.”Footnote 107 Then, subjects were randomly assigned one of two vignettes:

There is a 10% chance that Country B eventually uses its nuclear weapons to attack your country. Your country is [much more powerful than / similar in power to] Country B, and you can attack Country B's nuclear development sites with a [90% / 10%] chance of successfully stopping its nuclear program. As the leader of Country A, you get to decide the course of action.

Notice that only subjects’ objective level of state power varies across treatments. The level of threat—a 10 percent chance that the neighbor attacks—is the same. This ensures that all subjects face the same objective threat and addresses potential information equivalence concerns induced by the power treatment.Footnote 108 I use an objective-power prime, including the probability of a successful preventive strike, in line with rationalist understandings of relative power.Footnote 109 Again, I do not introduce a new definition of power but rather seek to unpack the underappreciated psychological effects that flow from relative capabilities.

To examine the proposed mechanism, the survey measured pretreatment beliefs about hostile intentions in IR. A reliance on prior beliefs is a classic example of intuitive thinking. Subjects expressed their agreement or disagreement with the item “Other countries often harbor aggressive intentions towards China” on a seven-point scale. If power activates a reliance on intuition, then the power treatment should amplify the effect of this prior belief on subjects’ threat assessments.

Following treatment, subjects answered two dependent variable questions using ten-point scales. To measure threat perception, subjects were asked, “How much of a threat do you think Country B poses to your country's security, where 0 represents ‘not a threat at all’ and 10 represents a ‘major threat’?” To measure aggression, subjects were asked, “How much would you favor sending your country's military to attack Country B's nuclear development sites, where 0 represents ‘strongly oppose’ and 10 represents ‘strongly support?” The expectation is that subjects assigned to the high-power condition will report higher threat perception than subjects in the power-symmetry condition, despite all subjects facing the same objective threat. Furthermore, power should increase aggressive tendencies, but this item was included primarily to assess the relative effect size of threat perception.

Figure 1 displays linear regression estimates for the treatment effect of power on threat perception (left panel) and on support for preventive attacks (right panel). Subjects randomly assigned to lead a powerful country are more likely to perceive the proliferating neighbor as threatening (coeff. = 0.25, p < .05) and more likely to support preventive strikes (coeff. = 0.26, p < .05), relative to subjects assigned to the baseline, power-symmetry condition. Figure 1 also displays standardized coefficients for pretreatment measures of militant internationalism and national attachment, two known predictors of threat perception and aggression. The effect of power on threat perception is similar in size to these well-known individual-level variables, although militant orientation is a noticeably larger predictor of aggression. But more important than coefficient size is the coefficient direction: the ability to address threats increases, rather than decreases, threat perception.

FIGURE 1. Experimental results from China

Furthermore, prior beliefs about the hostility of others’ intentions interact positively with the power treatment (Appendix A1). Individuals assigned to the high-power condition and predisposed to view the world as threatening are even more likely to evaluate the hypothetical neighbor as threatening (coeff. = 1.95, p < .05) and even more likely to support preventive attacks (coeff. = 2.95, p < .001). These moderation effects speak to my proposed mechanism: a reliance on prior beliefs in the formation of threat assessments is a classic indication of intuitive thinking.

Experimental Evidence from the US

In May 2024, I fielded an extended version of this counterproliferation experiment with 1,434 US-based adults recruited from Prolific. Most importantly, I wanted to conduct a more direct mediation test of the causal mechanism—that power activates intuitive thinking, which explains threat perception. The survey also included post-treatment items to verify that objective power induces a sense of power, held additional target-state attributes constant to address further information-equivalence concerns, and included a weakness condition. Respondents were first presented with a vignette:

Please take a moment to imagine that you are the leader of your own hypothetical country (‘Country A’). One of your neighboring countries (‘Country B’) has the following attributes:

• The country is not a military ally of your country.

• The country has low levels of trade with your country.

• The country is not a democracy.

• The country is half as wealthy as your country in terms of GDP.

• The country's population is not majority Christian.

• The country's population is primarily nonwhite.

• The country does not have large oil reserves.

Your country and Country B currently do not possess nuclear weapons. Although your countries have had tensions in the past, recent years have been relatively peaceful.

I chose these attributes in line with Dafoe, Zhang, and Caughey's information-equivalence analysis of Tomz and Weeks's vignette, which partly guides my vignette.Footnote 110 I fixed these attributes at values that would encourage threat perception in general, creating a harder test for the effect of power. The next screen assigned subjects to one of three conditions—high power, symmetric power, and low power—using this vignette:

Your intelligence services have obtained satellite images showing that Country B might be developing nuclear weapons. Country B's motives remain unclear, but if it develops nuclear weapons, there is a 10% chance that the country eventually uses its nuclear weapons to attack your country.

Your country is [much more powerful than / similar in power to / much less powerful than] Country B, and you can attack Country B's possible nuclear development sites with a [90% / 10% / 5%] chance of successfully stopping any possible nuclear program. As the leader of Country A, you get to decide the course of action.

Again, the objective level of threat is held constant at 10 percent across conditions to present subjects with the same objective security environment and to address information-equivalence concerns. As part of the power prime, I again include objective probabilities of a successful preventive attack in line with rationalist understandings of power. Again, psychologists often use objective power differences to prime the sense of power.

Following treatment, two items measured threat perception on seven-point (dis)agreement scales: “If Country B is developing nuclear weapons, Country B probably has aggressive intentions towards your country,” and “If Country B develops nuclear weapons, nearby countries will soon develop nuclear weapons in response.” The former assesses hostile intentions that are central to traditional definitions of threat perception.Footnote 111 The latter captures the domino logic that underpins classic historical examples of threat inflation, from the Fashoda Crisis to Cold War US foreign policy.Footnote 112 A further dependent variable measured aggressive tendencies on a ten-point (oppose–support) scale: “How much do you support sending your country's military to attack Country B's possible nuclear development sites?” The expectation is that high-power subjects will perceive greater threat and express more aggressive tendencies, relative to low-power and symmetric-power subjects.

Further, to verify that objective power induces a sense of power, respondents expressed seven-point (dis)agreement with two post-treatment items: “Your country has a great deal of control and influence over Country B,” and “Your country can get Country B to do what your country wants.” The expectation is that subjects assigned to the objective power condition will feel a greater sense of power.

As proxies for intuitive thinking, respondents expressed seven-point (dis)agreement with two items measured after treatment but before threat perception. One item captures the well-known bias of risk acceptance in the domain of losses: “It would be better to take risky military action now, rather than face the possible future losses from an attack by Country B.”Footnote 113 As Stein explains, “the impact of loss aversion on threat perception is considerable.”Footnote 114 A second item, “This situation should be addressed urgently, rather than in the future,” captures the psychological insight that perceived urgency is associated with intuitive thinking.Footnote 115 Finally, a third item was measured after threat perception on a ten-point scale: “How confident are you that your threat assessment of Country B is correct?” Stein shows that overconfidence in threat assessments leads to simplified views of others as implacably hostile, which inflates threat perception.Footnote 116 The expectation is that high-power subjects will rely more on these proxies for intuitive thinking, which in turn increase threat perception.

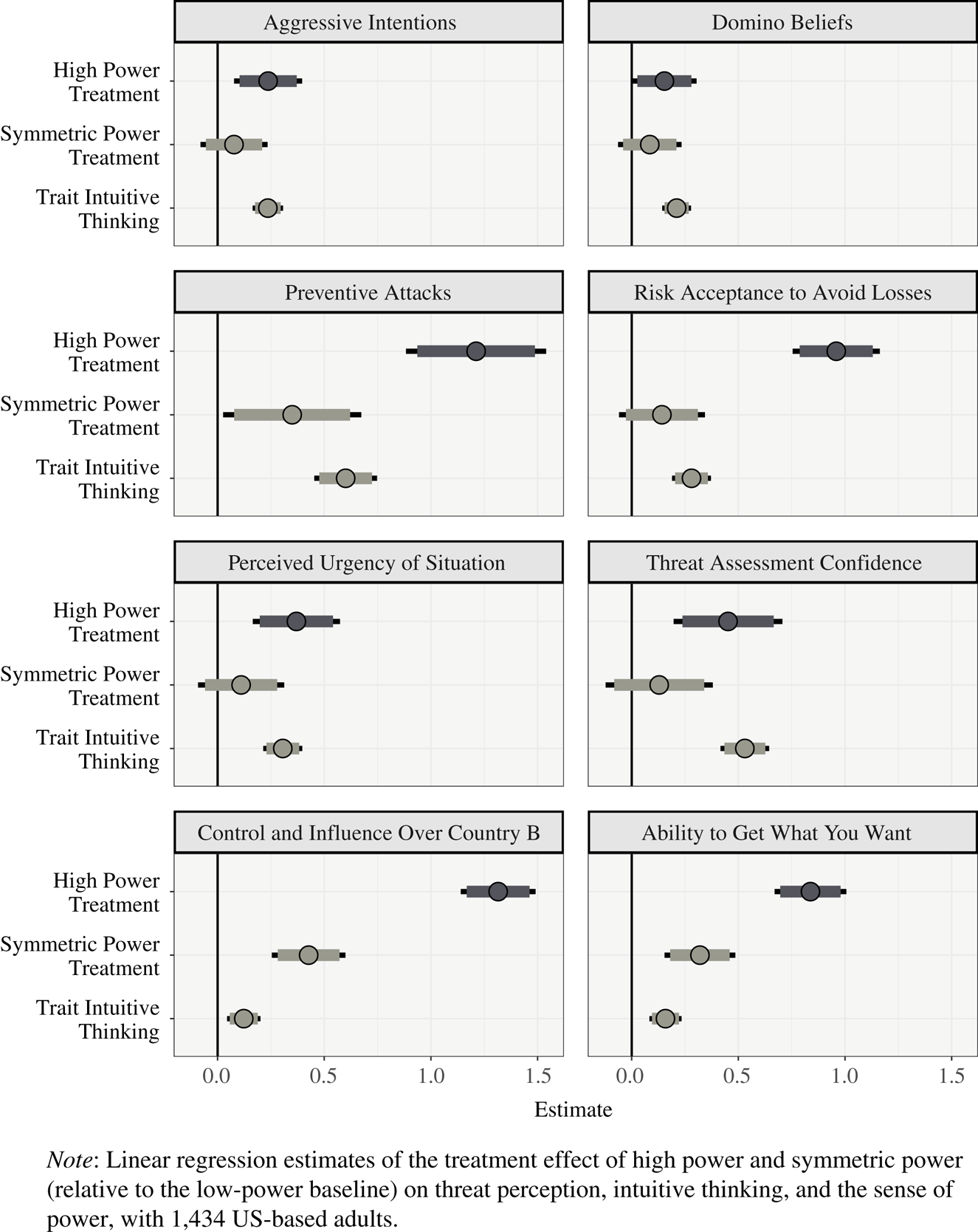

Figure 2 displays linear regression estimates for the treatment effect of high power and symmetric power (relative to low power) on each of these variables.Footnote 117 High-power subjects are more likely to believe that the neighbor has aggressive intentions (coeff. = 0.24, p < .01), more likely to fear that other countries will develop nuclear weapons in a domino-like fashion (coeff. = 0.15, p < .05), and more likely to support the use of preventive force to address these perceived threats (coeff. = 1.21, p < .001). Furthermore, subjects in the high-power condition are more likely to endorse risky military actions to avoid losses (coeff. = 0.96, p < .001), more likely to perceive the situation as urgent (coeff. = 0.37, p < .001), and more confident that their threat assessments are correct (coeff. = 0.45, p < .001). Finally, high-power subjects are more likely to feel that their country has a great deal of control and influence over Country B (coeff. = 1.32, p < .001), and believe that they can get Country B to do what they want (coeff. = 0.84, p < .001).

FIGURE 2. Experimental results from the US

Why does power increase threat perception? I use factor analysis to reduce the intuition mediators—risk acceptance, urgency, and threat-assessment confidence—to unidimensional factor scores, where higher values indicate more intuitive thinking. A mediation analysis using the Imai and colleagues framework confirms that intuition fully mediates the effect of objective power on aggressive intentions (ACME coeff. = 0.31, p < .001) and domino beliefs (ACME coeff. = 0.16, p < .001).Footnote 118 Furthermore, intuition mediates 77 percent of the effect of objective power on support for preventive strikes (ACME coeff. = 0.93, p < .001). Further, in line with my expectations, the sense of power mediates the effect of objective power on threat perception and explains positive variance in intuitive thinking (Appendix A2.1.1). Power is also a feeling, and this feeling increases threat perception.

To verify that these intuition mediators actually capture intuitive thinking, I note that the survey measured trait differences in intuitive thinking using items from the well-established Rational Experiential Inventory.Footnote 119 The scale includes items like “I believe in trusting my hunches.” In Figure 2 we see that subjects with more intuitive thinking styles are more likely to display loss aversion (coeff. = 0.28, p < .001), perceive the situation as urgent (coeff. = 0.31, p < .001), and express greater confidence in their threat assessments (coeff. = 0.53, p < .001). Importantly, material power shifts subjects’ responses in the same direction as this trait-level measure of intuitive thinking. The powerful think from the gut.

Finally, Appendix A2.2 presents a third original survey that experimentally induces intuition using time pressure, a method used in psychological research.Footnote 120 It was fielded in the US and centered on a hypothetical future Taiwan scenario. I find that individuals randomly placed under time pressure are more likely to perceive China as a serious threat to US security and more likely to believe that China harbors aggressive intentions toward the US. This experimentally verifies the link between intuition and threat perception, beyond the measured proxies for intuition we have seen. All of this evidence provides strong experimental support for the expectation that relative state power activates intuitive thinking, which increases threat perception.

Correlational Evidence from Russian Elites

Do these stylized experimental results mirror the views of actual elites? This section reanalyzes a 2020 survey of Russian elites by Zimmerman, Rivera, and Kalinin.Footnote 121 It was fielded in Moscow via face-to-face interviews with 245 individuals. They included members of the executive branch, military and security services, and legislators who work on foreign policy, as well as members of the media, the academy, private business, and state-owned corporations.Footnote 122 Importantly, the survey includes unusually rich measures of the sense of Russian power, various forms of threat perception, and a host of individual- and strategic-level variables that serve as competing explanations of threat perception.

To measure the sense of Russian power, I use three survey items. Two items asked, in the twenty years since Putin became president, whether the “influence of Russia in the world” and Russia's “military readiness and strength” have increased, decreased, or remained unchanged. A third item omitted reference to Putin, asking, “What impact do you think that Russia's foreign policy in recent years has had on Russia's international influence?” This item used a five-point negative-versus-positive impact scale. The items display reasonable alpha reliability (α = 0.70) and capture the sense of strength and influence at the core of my concept of the sense of power. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of these items—namely assessments of rising versus declining power—extends my expectations to the context of shifting power. I reduce these items to unidimensional factor scores, where higher values represent a greater sense of Russian power.Footnote 123

I examine three items that capture threat perception across different types of strategic threat. The first assesses US threat perception with a yes/no question: “Do you think that the US represents a threat to Russian national security?” A second item assesses the threat posed by NATO, asking whether “further expansion of NATO to countries in the Near Abroad” poses “the greatest threat to the security of Russia” versus “does not represent any threat whatsoever,” with responses on a five-point scale. Finally, an item assesses the threat posed by Ukraine: “How friendly or hostile do you think Ukraine is toward Russia today?” with responses on a five-point scale from “very friendly” to “very hostile.” Whereas the counterproliferation experiments used hypothetical countries, these items capture a range of important, real-world strategic concerns for Russia.

Figure 3 displays regression estimates for the relationships between the sense of Russian power and perceptions of threat from the US, NATO, and Ukraine. Elites who feel a greater sense of Russian power arrive at higher assessments of threat across each potential concern (US coeff. = 0.76, p < .001; NATO coeff. = 0.18, p < .05; Ukraine coeff. = 0.18, p < .001). As in the previous experiments, these results directly contrast with conventional IR expectations: a sense of Russian strength and influence is associated with feeling more threatened.

FIGURE 3. Reanalysis of a 2020 survey of Russian elites

Consider alternative explanations. Most notably, IR scholars expect state interests to expand with power.Footnote 124 Here, the sense of power does not inflate threat so much as material power expands the range of new material threats. To measure Russian interests, respondents were asked whether the national interests of Russia “should extend beyond its current territory” or “should be limited to its current territory.” Elites who believe the former are more likely to perceive a US or NATO threat (Figure 3). However, those same individuals are less likely to perceive a Ukrainian threat. These differences in coefficient direction speak to an important distinction between interest expansion and the sense of power. Interest beliefs suggest a difference in kind, namely concerns about the US versus Ukraine depending on beliefs about interest expansion. The sense of power suggests a difference in degree: a greater sense of power is associated with higher threat perception, regardless of the specific issue or threat.

Further, consider individual differences common in behavioral IR research. Prior military service, a predictor of elite hawkishness,Footnote 125 does not significantly explain threat perception across any of these possible threats. Militant orientation explains US and NATO threat perception but misses perceptions of a Ukrainian threat, an effect captured by the sense of power and an effect that would prove consequential, with Russia's invasion of Ukraine coming just two years after this survey was fielded. Importantly, these results control for membership in United Russia—Russia's ruling party and Putin's de facto party—which serves as a proxy for support for Putin. That is, the sense of Russian power does explanatory work beyond support for Putin. All of this suggests that the sense of Russian power offers a more consistent explanation of elite threat perception than a range of other causes commonly mentioned in IR research.

Given the limitations of correlational data, Appendix A2.3 reports a supplementary survey experiment that mimics the items used in the Russian elite survey. In a sample of US-based adults, respondents who were randomly told that US power has increased over the past ten years are more likely to believe that “the US faces many security threats” in IR, relative to subjects assigned to a declining US power condition (coeff. = 0.33, p < .05). This provides a cross-national experimental check on the correlational items used in the Russian elite survey.

Together, these results extend the main finding from the counterproliferation experiments to a sample of Russian elites across a range of real-world threats. Previous explanations are certainly part of the threat perception story, but IR scholars have overlooked the independent role of the sense of power. Further, rising power seems to exert the same effect on threat perception as static power comparisons, extending my results to a dynamic setting. The next (and final) empirical section exits the survey world to examine a much broader period of time.

Textual Evidence from Cold War US Elites

The studies we have seen so far afford experimental control, as well as an initial indication of external validity in the Russian elite survey. This final empirical section meets foreign policy elites in their natural environment, using textual data to test my argument across all available Cold War documents in the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS). Psychologists often use text analysis to study perceptual and cognitive processes.Footnote 126 For the purposes of this paper, textual data provide rich insights into decision makers’ perceptions of power. These perceptions are unavailable in large-N data sets, which often use GDP or CINC scores as proxies for power.Footnote 127

I focus on internal US government documents during the Cold War for two reasons. First, the Cold War presents a harder test for the argument than the US's post–Cold War unipolar moment. That moment was an exceptional case of exposure to the psychological consequences of power and thus could be critiqued on the grounds of exceptionality. Second, the use of intra-governmental documents helps to avoid critiques sometimes lodged against analyses of leaders’ speeches in public fora like the United Nations, settings that might offer incentives to dissemble.

To obtain the documents, I manually downloaded every available Cold War–era volume in the FRUS from the website of the US State Department's Office of the Historian. The FRUS represents the “official documentary historical record of major US foreign policy decisions and diplomatic activity.”Footnote 128 This corpus is one of the most commonly used sources for historical analyses of US security policy in general and recent text analyses of US threat perception in particular.Footnote 129 Documents in the FRUS were often previously classified and include intra-governmental memoranda, correspondence, and diplomatic cables, among others. The volumes under consideration begin in 1945 with the Truman administration and fade out by 1988 with the Reagan administration, where many volumes are still under declassification review. The result is 300 total volumes, which I converted to plain text for analysis. The corpus contains over 142 million words.

Close readings of the texts provide prima facie indication that the sense of US power often co-appears with perceptions of threat. Consider a March 1970 National Security Council meeting.Footnote 130 President Nixon plainly remarks, “The United States is the first nation in the world in strength.” Yet, surrounding this observation is an extensive list of potential dangers. Deputy Under Secretary of Defense David Packard explains:

We were concerned about the SS–9 triplet [a Soviet submarine]. We still don't know whether they are MIRV'd or not … We are worried that they can hit our Minuteman without much new construction … With these deployed, there will be a serious threat to our cities and airfields. Then our land-based force would be in jeopardy and the bombers would be in jeopardy … If they have ABM then that would be bad news for us.

Notable here is the presence of domino logic, a classic threat-inflation mechanism, expressed within the context of certainty that the US “is the first nation in the world in strength.”

This pattern is not unique to the Nixon administration. Consider a 1962 memorandum to President Kennedy authored by high-ranking officials across the defense and intelligence communities.Footnote 131 The officials assess that the “Soviet Union [has] a militarily inferior position relative to the US under almost all circumstances of war outbreak,” a clear statement of US strength. Yet, in the same context, the memo outlines these warnings:

Among the other changes forecast in recent national estimates are the growing submarine-launched missile threat, the rapid Soviet development of an anti-ballistic missile program, larger MRBM-IRBM forces than previously estimated, the possibility of Soviet weapons in space, and the intensifying problem of civil defense.

Of course, it is not surprising to find threats listed in a report tasked with threat assessment. The empirical question is whether threat perception is more likely to occur in the context of a sense of strength, versus a sense of weakness. According to IR theory, a sense of weakness should be associated more strongly with threat perception. I expect the opposite. A large-scale text analysis permits adjudication between the two.

I use word embeddings to analyze the texts; this is a method uniquely suited to capture perceptions. As Caliskan and Lewis explain, cognitive scientists helped pioneer the development of word embeddings in the 1990s.Footnote 132 These models were later refined and popularized by the machine learning community.Footnote 133 Traditional models of political text rely on word frequencies, namely counts of terms in a given document.Footnote 134 By contrast, embedding models use word co-occurrences to operationalize the notion that we can know a word by the company it keeps.Footnote 135 Compared to count-based models of text, embeddings more powerfully capture intuitive thinking patterns contained in textual data, such as implicit biases and racial and gender stereotypes.Footnote 136

To estimate the embeddings, I use the Global Vectors for Word Representation (GloVe) model,Footnote 137 arguably the most common embedding model in the social sciences.Footnote 138 To preprocess the texts, I lowercase the terms, stem the terms (e.g., hostile and hostility both become hostil*), remove punctuation, and remove terms that appear fewer than ten times across the corpus.

Next, the documents are represented as a term co-occurrence matrix that counts the appearance of each unique term within a fixed distance from every other term in the corpus. I use a window of six words before and after, which is standard in embeddings research.Footnote 139 As an example, this matrix quantifies the frequency with which US decision makers use the terms soviet and threat within a six-word window, which is probably more often than the use of the terms soviet and friend within a six-word window. These raw co-occurrence statistics alone would tell us, here, that US decision makers refer to the Soviets as a threat more often than a friend.

Because such a matrix can be very large—every unique term by every unique term in dimensionality—the GloVe model innovates by using an ordinary least squares estimator to reduce the matrix to a lower-dimensional representation. That is, GloVe basically uses a big regression to reduce the matrix. The output of this reduction procedure is a matrix with dimensions of “every unique term” by “arbitrary coordinates.” I fit the model in 300 arbitrary dimensions, perhaps the most standard dimensionality choice.Footnote 140 The output of the model is a set of 300 coordinates (the beta coefficients from the OLS estimator) for each unique term in the corpus. These coordinates quantify the location of every unique term in the estimated vector space. A term in two dimensions would be akin to a term's latitude and longitude on a semantic map. For example, plotting the vectors for soviet, threat, and friend in two dimensions would reveal that soviet and threat are closer on this map than soviet and friend. At 300 dimensions, the result is an incredibly rich semantic space.

With these word coordinates in hand, the final step is to define dictionary terms that capture my theoretical constructs. I am interested in three constructs, captured with these terms:

• US power: power, stronger, strong, capabl*, capac*, abl*.

• US weakness: powerless, weaker, weak, incap*, incapacit*, unabl*.

• Threat perception: [soviet, russian / china, chines* / vietcong, north, vietnam], threat, aggress*, hostil*.

Again, I use objective power terms (such as stronger versus weaker) to remain consistent with conventional definitions of power in IR. Psychologists of power, and the experimental results we have seen, show that material power induces a sense of power. To ensure that US decision makers are discussing US (and not Soviet) power, I average the power and weakness terms with the terms us, we, and our. Further, the threat perception dictionary uses standard terms from IR theory to capture threat perception. I examine various possible threats, including the Soviet Union, China, and the Viet Cong.

I estimate two quantities of interest. The first is the relationship between the sense of US power and threat perception. In the survey data, the sense of power is positively correlated with (and experimentally increases) threat perception. In an embeddings context, cosine similarity provides a similar estimate, essentially a correlation coefficient suited to vector spaces. The procedure is similar to that of Caliskan, Bryson, and Narayanan;Footnote 141 it estimates the average cosine similarities between the power terms and threat perception, as well as the similarities between the weakness terms and threat perception, and then takes the difference between these two quantities. As in a difference-in-differences estimate, larger values indicate that the sense of power is more strongly correlated with threat perception than weakness is correlated with threat perception.

The other quantity of interest is the mechanism that underpins this relationship. I expect the sense of power to activate more intuitive thinking, which in turn explains the association between power and threat perception. I use four terms as proxies for intuitive thinking: feel, impress*, sens*, instinct*. To be clear, these terms do not necessarily capture “fast” thinking or automaticity. Rather, they proxy for the types of words decision makers are more likely to use when expressing their intuitions and “gut instincts.”

To estimate this mechanistic relationship, I use the power of mere averages in the embedding space to operationalize Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen's “average controlled direct effect” in the correlational context of word embeddings.Footnote 142 The intuition is simple: if intuitive thinking links the sense of power to threat perception, then the cosine similarity between power and threat should significantly decrease when averaging the power and weakness terms with intuition terms. Holding intuition terms constant across power levels blocks the role of words that proxy for intuition.

Finally, I construct nonparametric confidence intervals using the resampling procedure described by Kozlowski, Taddy, and Evans.Footnote 143 The procedure resamples the underlying corpus with replacement to construct twenty resampled corpora, refits an embedding model to each resampled corpus, and then recalculates the cosine estimates of interest. The result is twenty cosine estimates, ordered such that the second and nineteenth estimates span a 90 percent nonparametric confidence interval.

Figure 4(A) displays the first set of estimates. The top panel displays the cosine similarity (that is, the correlation) between the sense of US power and Soviet, Chinese, and Viet Cong threat perception. The correlations are positive and statistically significant. As in the surveys, the interpretation here is that US decision makers are more likely to perceive the Soviets as threatening (as represented by, for example, soviet hostile) when they feel a sense of US power (our strength) than when they feel a sense of US weakness (our weakness). Again, it is not surprising to see threat perception expressed in these documents. Bureaucratic officials may inflate threats to attract resources to their cause. But it is surprising that elites are more likely to express a sense of threat in the context of US strength as opposed to weakness.

FIGURE 4. Text analysis of Cold War US elite threat perception

Before proceeding to mechanistic estimates, it is worth noting that the bottom panel of Figure 4(A) displays the cosine similarity between the sense of US power and terms that proxy for intuitive thinking. As psychology of power research finds, the sense of US strength correlates positively with terms that reflect relatively intuitive thinking (cosine sim = 0.048, 90% CI [0.040, 0.059]). The feeling of power activates a reliance on gut instincts.

Do terms that proxy for intuition explain the cosine similarity between power and threat perception? Figure 4(B) displays these estimates, inspired by Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen's average controlled direct effect.Footnote 144 The first point estimates, labeled Threat Perception, simply reproduce the same correlations between power and threat perception reported in Figure 4(A). The second coefficient re-estimates this same correlation but averages the power and weakness terms with intuition terms. Importantly, this significantly decreases the cosine similarity between power and threat perception. Each of these reductions in the correlation between the sense of power and threat perception is statistically significant. In Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen's framework, this difference is known as the “eliminated effect” and provides evidence for an intuition-mechanism pathway.

Appendix A4.2 conducts this same text analysis in a dynamic context, focusing on perceptions of rising versus declining US power. The results are substantively identical to Figure 4. This provides further evidence that the sense of power correlates positively with threat perception across static and dynamic power comparisons, and further evidence that intuition explains this relationship. Across all of these results, I find no evidence that power decreases threat perception.

Conclusion: Toward a Politics Among Humans

A basic tenet of IR theory is that material power affords security. Power should decrease threat perception. However, almost no behavioral IR work assesses this claim. Power is a relative material attribute, but power is also a feeling and an experience that changes individuals.Footnote 145 The results reveal a psychological tension in IR theory. Power, the capacity states need to address threats, makes individuals feel more threatened. The wedding of human-nature sensibilities from classical realism with the structural forces that motivate neorealism suggests a possible behavioral realist agenda in future IR research.Footnote 146

The theoretical implications are diverse. Leaders of weaker states might underbalanceFootnote 147 because they do not see the world as very dangerous. Powerful states might overextendFootnote 148 because power primes leaders to perceive an ever-expanding range of threats. Given the stark difference in capabilities, perhaps the feeling of power explains the US's overreaction to “terrorism” in the post–September 11 world. For the nuclear revolution debate, the feeling of power that flows from possession of nuclear weapons might help explain persistent threat perception among nuclear-armed states.Footnote 149 Finally, perhaps the sense of power explains the most pernicious forms of nationalism—a feeling of strength and exceptionalism combined with certainty that outgroups, like immigrants, seek to do us harm.Footnote 150 The bottom-up, individual differences commonly studied in psychological IR are certainly part of these stories. But power also changes individuals in a top-down, first image reversed fashion.

The connection of power to intuitive thinking is also relevant beyond threat perception. For example, IR research suggests that elites are more likely to be overconfident than non-elites.Footnote 151 The sense of power might be one source of this overconfidence.Footnote 152 Further, the feeling of power activates implicit bias and prejudice.Footnote 153 Perhaps the sense of power helps explain racial prejudice among Western leaders and publics toward countries and peoples racialized as nonwhite.Footnote 154

Metatheoretically, this paper's first image reversed argument offers one solution to the “aggregation problem.” IR traditionally conceives of psychology as a bottom-up process in which individual differences compete with domestic and international variables to explain outcomes. As Powell explains, this model requires that psychological IR aggregate differences “up” to the state level.Footnote 155 Inverting the causal arrow, I show that psychology is also a dependent variable. Power makes individuals see the world in more threatening terms, with fewer differences to aggregate. Further, while I focus on elite decision makers, I find similar effects across elite and public samples. This aligns with recent research that documents striking similarities across elite and public psychology,Footnote 156 suggesting that the aggregation problem has been overstated in IR.

All of this takes on pressing salience in the context of US–China relations today. Jessica Weiss argues that US foreign policy overestimates the threat posed by China.Footnote 157 Meanwhile, Cai Xia argues that paranoia increasingly pervades Chinese foreign policy.Footnote 158 US elites today respond with strategies of further power accumulation under the assumption that power will make the US feel safer.Footnote 159 This policy is misguided at the level of psychology: increasing a sense of US power relative to China is likely to further fuel US perceptions of a China threat.

A more sensible US policy would exhibit empathy for the concerns of a rising power, a wider historical perspective on a millennia-old country, and appreciation for the complexity of China's domestic situation.Footnote 160 That is, think like the weak. McDermott suggests that the feeling of power provides a strong basis to expect that rising power begets the aggression described by power transition theory.Footnote 161 This paper goes further to show that this aggressiveness flows from a sense of threat. Rising powers, rather than declining powers, may be more prone to fear. If so, US efforts to deter China through strength—rather than defuse threats through diplomacy—could backfire, causing China to feel even less secure.

The Sword of Damocles, an ancient Greek parable, suggests that a life of power is fraught with ever-present danger. I suggest that the dangling sword is more often a delusion: threats are often a figment of power-induced imagination. The most worrisome situation would be one in which the US and China both feel that they possess a power advantage. As Blainey points out, “wars usually begin when two nations disagree on their relative strength.”Footnote 162 To this statement about mutual optimism, this paper adds a mutual sense of threat.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZEKIQN>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818324000407>.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Steve Brooks, Skyler Cranmer, Rick Herrmann, Kara Hooser, Josh Kertzer, Alex Lin, Jonathan Markowitz, Rose McDermott, Steven Miller, David Peterson, Brian Rathbun, Johanna Rodehau-Noack, Randy Schweller, Jack Snyder, Janice Stein, Bill Wohlforth, Sherry Zaks, the editors and anonymous reviewers, and audiences at Columbia, Dartmouth, Harvard, Notre Dame, Ohio State, USC, and UCSD. The author is indebted to Ohio State's Program for the Study of Realist Foreign Policy for research support and to Haoming Xiong for translation assistance.