High consumption of discretionary energy dense foods and drinks, such as lollies (sweets), cakes, biscuits and chips (crisps), has been associated with a greater risk of developing obesity and a range of chronic diseases(Reference Chiuve, Fung and Rimm1–Reference Jessri, Wolfinger and Lou3). Childhood dietary experiences are an important contributor to this growing burden of disease, with poor dietary habits and food preferences established in early life tracking through into adult life(Reference Pearson, Salmon and Campbell4–Reference Mikkila, Rasanen and Raitakari6). The 2011–2012 Australian National Health Survey suggested that 30 % of 2- to 3-year-old children’s daily energy intake was from discretionary foods(7). Given that over 70 % of 2- to 6-year-old children’s energy intake is likely to take place at home(Reference Poti and Popkin8), parents’ management of young children’s home food environment is potentially an important influence on children’s diets.

Parents manage children’s intake of discretionary foods using restrictive feeding practices to control what, how much and when their children consume these foods(Reference Birch9). Short-term experimental studies have suggested that such restrictive feeding practices are counterproductive(Reference Fisher and Birch10–Reference Rollins, Loken and Savage14). These studies have consistently observed that children’s desire for and intake of a restricted food (i.e. foods targeted for restriction) is greater relative to an unrestricted food in the period immediately following restriction. However, the two experiments performed by Ogden et al. (Reference Ogden, Cordey and Cutler13) that extended for longer periods than the other experiments (i.e. 2 d and 2 weeks) also indicated that the alternative of allowing child free access to a restricted food (chocolate) resulted in higher child intake of that food over the duration of the experiments. This suggests that a lack of restriction may also be problematic. It is, therefore, unclear how the overall findings of these experiments relate to children’s development of preferences for and intake of restricted foods within their natural environment over time.

Cohort studies have attempted to measure the effects of parent restrictive feeding in children’s natural environment. Of these, longitudinal studies measuring parent’s use of restriction via self-report survey have indicated either no significant effect on child weight(Reference Campbell, Andrianopoulos and Hesketh15,Reference Farrow and Blissett16) or that restrictive feeding practices are associated with lower weight gain among younger children(Reference Campbell, Andrianopoulos and Hesketh15–Reference Webber, Cooke and Hill17). The Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) restriction scale(Reference Birch, Fisher and Grimm-Thomas18) has most commonly been used by cohort studies to measure parent restriction. Other scales developed have also incorporated items from this scale to measure restriction(Reference Jansen, Mallan and Nicholson19,Reference Musher-Eizenman and Holub20) . This scale was intended to differentiate high and low restricting parents, but the scale does not clearly reflect this distinction.

The majority of items in the CFQ restriction scale ask parents whether they ‘have to be sure’ or ‘guide or regulate’ their child from consuming ‘too many’ or ‘too much’ ‘sweet’, ‘junk’, ‘favourite’ or ‘high fat’ foods. These items do not directly assess the specific parenting practices used to restrict these foods, nor the success of such practices in achieving the aim of restricting children’s intake of these foods. Issues regarding the extent to which this scale can differentiate high and low restricting parents are illustrated by a prospective trial that found mothers’ scores on the CFQ restriction scale were significantly reduced when children’s access to target foods was totally restricted at home(Reference Holland, Kolko and Stein21). This indicates that high scores on the CFQ restriction scale could potentially reflect a parent’s need to ‘guide or regulate’ their child’s eating of target foods associated with greater access, rather than reflecting the level of restricted child intake applied by parents. Thus, classification of high or low restricting parents may be better captured by examining children’s intake of ‘restricted foods’ rather than the practices used by parents or their perceived ‘need’ to regulate their child’s access to these foods. Following on from this, is the limited research regarding the specific foods and drinks targeted for restriction by parents to inform the selection of foods and drinks for examination. As a result, an array of different foods and drinks have been used in studies to represent restricted foods and drinks but only one study identified had included restricted items based on parent’s reports(Reference Gubbels, Kremers and Stafleu22).

Another issue present in cohort studies examining the impact of restrictive feeding practices is the use of a variety of child outcome measures. Typically, child weight status has been used as a primary outcome measure, reflecting the interest in effects on childhood obesity. However, arguably the key outcome of interest is whether restriction increases a child’s desire for restricted foods and hence future dietary choices in the absence of parental control, as Fisher and Birch(Reference Fisher and Birch10) suggest. Thus, a more proximal measure of the effect of restrictive feeding practices may be children’s liking for the specific foods and drinks that are restricted. However, when considering children’s liking for restricted foods, it is relevant to consider other factors that may influence child liking for the high density, sweet or salty foods likely to be targeted for restriction.

There is robust evidence linking children’s early exposure and frequency of intake with their liking for foods(Reference Caton, Ahern and Remy23–Reference Wardle and Cooke25), but this knowledge has almost entirely focused on potentially neophobic foods, such as vegetables, that parents typically want to encourage. There has been limited research on whether a similar association exists for more palatable foods that are likely to be targeted for restriction. Children’s development of liking for the high density, sweet or salty foods potentially targeted for restriction may differ due to children’s innate preferences for such foods(Reference Birch9). However, some studies have indicated that repeated exposure to fruit juices and carbonated sweet drinks is associated with increased child liking and wanting for them(Reference Hartvig, Hausner and Wendin26–Reference Grimm, Harnack and Story28). In addition, Sullivan and Birch(Reference Sullivan and Birch29) found that repeated exposure to either sweet, salty or plain flavoured tofu increased 4- to 5-year-old children’s preferences for the flavour they received. More recently, Mallan et al. (Reference Mallan, Fildes and Magarey30) found a significant correlation between child exposure by 14 months and child liking at 3·7 years for a group of seventeen non-core foods that could potentially be foods targeted for restriction. These studies appear to suggest that lower rather than higher restriction of intake may contribute to children’s preferences for a restricted food or drink, with the implication that restriction of intake is beneficial.

Another factor found to be associated with children’s food preferences is maternal food preferences(Reference Cooke, Wardle and Gibson31,Reference Falciglia, Pabst and Couch32) . Unlike preference for other foods which have a substantial heritable component, genetic studies have indicated that child liking for highly palatable snack and dessert foods is explained more by shared environmental effects(Reference Fildes, van Jaarsveld and Llewellyn33,Reference Breen, Plomin and Wardle34) . Related to this, maternal liking for a food has been linked to environmental child exposure. Howard et al. (Reference Howard, Mallan and Byrne35) found that mothers were significantly more likely to offer a food they also liked to their 2-year-old child and mothers modelling the consumption of these foods may influence child liking(Reference Romero, Epstein and Salvy36,Reference Salvy, Elmo and Nitecki37) .

Authors have also proposed that different parental restrictive feeding practices may have variable effects on child liking and hence intake of restricted foods. Ogden et al. (Reference Ogden, Reynolds and Smith38) proposed that overt and covert controlling feeding practices have differing effects on child intake of different foods and, more recently, Rollins et al. (Reference Rollins, Savage and Fisher39) proposed that coercive restrictive feeding practices may have a different effect on child diet-related outcomes than restriction via structured food environments. However, qualitative studies suggest that individual mothers tend to use multiple practices to accomplish child-feeding goals rather than abiding by rigid patterns of practices(Reference Ventura, Gromis and Lohse40–Reference Carnell, Cooke and Cheng42), including both overt and covert practices(Reference Ventura, Gromis and Lohse40). In fact, the study by Ogden et al. (Reference Ogden, Reynolds and Smith38) also found a positive correlation for use of overt and covert controlling feeding practices by the same mother (r = 0·3, P = 0·02). Given the likelihood that parents are using a combination of practices to restrict children’s intake of particular foods, further research is required to clearly distinguish differences in individual parent practices within children’s natural environments before this variable can be effectively assessed.

In summary, there is a lack of consensus in the literature on the impact of restrictive feeding practices on children’s diets. Furthermore, measurement in cohort studies has primarily focused on attempting to measure parent restrictive feeding behaviours, with the level of restriction achieved by parents (i.e. child intake) rarely being included as an independent variable in the examination of restrictive feeding. Mothers’ own liking for restricted foods might also influence child liking via child access(Reference Howard, Mallan and Byrne35), role modelling(Reference Romero, Epstein and Salvy36,Reference Salvy, Elmo and Nitecki37) , inheritance(Reference Fildes, van Jaarsveld and Llewellyn33,Reference Breen, Plomin and Wardle34) or other mediating factors. The purpose of the present study was to examine associations between variables of current child intake, mothers’ own liking and child early exposure with child liking for a selection of foods and drinks, which were reported to be commonly restricted by a sample of mothers of 5 year olds(Reference Jackson43). The first aim of this study was to examine descriptive data patterns of child intake frequencies of the selected restricted foods and drinks, as well as children’s progressive introduction to these foods and drinks at ages 14 months, 2 years, 3·7 years and 5 years. The second aim was to examine prediction of child liking for the same selected restricted foods and drinks at 5 years old by variables of child high intake frequency (at 5 years old), mother’s own high liking and child early exposure to the selected foods and drinks.

Method

Measures

This study presents secondary analysis of data from the NOURISH randomised controlled trial(Reference Daniels, Magarey and Battistutta44). This trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy of two sets of six parent group education sessions designed to improve early feeding practices, which were provided fortnightly when children were 4–7 months and 13–16 months old. The control arm of this trial had access to ‘usual child health services’, which included information and support for child feeding, growth and development via child health clinic services, a telephone helpline and website. The trial recruited 698 mothers postnatally from major maternity hospitals in the cities of Brisbane and Adelaide in Australia during 2008 and 2009. Inclusion criteria were English speaking first-time mothers (≥18 years) with healthy term infants (>35 weeks, >2500 g). Written consent was given, and participants were randomised according to a permuted-blocks randomisation schedule. The data collection method was via self-completed questionnaire, which contained several widely used and previously validated questionnaires and some study-specific items related to infant and child feeding, which were well accepted in pilot studies performed for the NOURISH trial(Reference Daniels, Magarey and Battistutta44). Mother and child length, height and weight were measured at relevant time points using standard protocols.

The present study’s sample included 211 mother and child dyads participating in the control arm of the NOURISH trial, who were still actively enrolled in the study at child aged 5 years. Those participating in the intervention arm of the trial were excluded because exposure to the NOURISH intervention may have influenced mothers’ feeding practices and impacted on the variables examined in the present study. NOURISH trail data at the following child age time points were used in the present study: 14 months (13·7 ± 1·3 months), 2 years (24·1 ± 0·7 months), 3·7 years (44·5 ± 3·1 months) and 5 years (60·0 ± 0·5 months).

Selected restricted foods and drinks

Selection of restricted foods and drinks included in the analyses was informed by mothers’ reports of items commonly targeted for restriction in an unpublished qualitative study, which involved a sub-sample of participants in the present study(Reference Jackson43). Nine items were selected for inclusion in analysis: sweet biscuits, cakes, lollies (sweets), savoury biscuits, potato chips (crisps), fast foods (e.g., KFC, McDonalds), soft drink/fizzy drink (carbonated sweet drinks), fruit drink (sweetened fruit flavoured drinks) and ice cream.

Child age first tried

A six-point food and drink liking scale developed by Wardle et al. (Reference Wardle, Sanderson and Leigh Gibson45) (i.e. 1 = likes a lot, 2 = likes a little, 3 =neither likes/dislikes, 4 = dislikes a little, 5 = dislikes a lot and 6 = never tried) was used to measure whether children had tried a food or drink item. For regression analysis, responses were dichotomised into tried (points 1–5; reference group) and never tried (point 6) for each of the selected restricted items. The child early exposure variable was determined by children having tried the following items by 14 months (sweet biscuits, cakes, lollies (sweets), savoury biscuits and potato chips (crisps)) or by 2 years (soft drink/fizzy drink, fruit drink and fast foods).

Child high liking

The same tool described above was also used to measure child high liking for each selected restricted item at child aged 5 years. For this measure, the scale was dichotomised into likes a lot (point 1; reference group) and likes a little to dislikes a lot (points 2–5). Responses of never tried (point 6) were excluded from analysis because the child’s liking for the item could not be ascertained if they had not tried it.

Mothers’ own high liking

The tool described above and dichotomised in the same way as for child high liking was used to measure mothers’ own high liking for each of the selected restricted items. Data for mothers’ liking of foods and drinks were collected at the child aged 2 years assessment point.

Current child intake frequency

The Child Dietary Questionnaire (CDQ)(Reference Magarey, Golley and Spurrier46) was used to measure child intake frequency of the selected restricted foods (sweet biscuits and cakes, lollies (sweets), savoury biscuits and chips (crisps), takeaway (e.g., McDonalds, KFC, Fish and Chips, Chicken Shop)) at child aged 5 years. The response scale asked parents to report child intake frequency of selected items in the past 7 d (frequency response options = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6+ times). For regression analyses, responses were dichotomised to enable a suitable spread of data to meet statistical assumptions. Responses were dichotomised into two times a week or more (child high intake frequency; reference group) and less than two times a week (child non-high intake frequency) for all items except fast foods. Fast foods were consumed less frequently and required data to be dichotomised into once a week or more (child high intake frequency; reference group) and less than once a week (child non-high intake frequency).

A separate scale developed by the NOURISH investigators(Reference Daniels, Magarey and Battistutta44) was used to measure child intake frequency of selected restricted drinks (soft drink/fizzy drink and fruit drink) at child aged 5 years. The response scale asked parents to report child intake frequency of the selected drink items per week (frequency response options = never, <1, 1–3, 4–6, 6+ times). As frequency of intake of these drinks was low in this sample, responses were dichotomised into less than once a week or more (child high intake frequency; reference group) and never (child non-high intake frequency) for regression analyses.

Covariates

Six maternal and child characteristics were selected for examination as covariates based on their potential association with mothers’ use of restrictive feeding practices reported in the literature. These included child gender (male or female), child birth weight z-score (obtained from hospital records), maternal education (university or non-university at the child aged 4 months assessment point), maternal age (at child birth), maternal BMI (kg/m2 measured using a standard protocol at the child aged 4 months assessment point) and duration of breast-feeding (weeks duration measured at the child aged 2 years assessment point). However, child and maternal characteristics may be associated with child exposure and intake of restricted foods and drinks and could potentially distort the effects shown by the predictors rather than be independent confounders. For example, Howard et al. (Reference Howard, Mallan and Byrne35) found characteristics of younger maternal age, higher maternal BMI, shorter duration of breast-feeding and heavier child birth weight to be positively associated with children having tried a range of non-core foods by 2 years of age. For this reason, characteristic covariates were examined separately.

Data analysis

Descriptive data were examined for patterns of frequency of child intake at 5 years and the percentage of children in the sample that had tried each of the selected restricted items at the following age time points: 14 months, 2 years, 3·7 years and 5 years. Multivariable binary logistic regressions were subsequently performed including three predictors (child high intake frequency, mother’s own high liking and child early exposure) and the six selected child and maternal characteristic covariates (child gender, child birth weight z-score, maternal education, maternal age, maternal BMI and duration of breast-feeding), with child high liking as the outcome variable. Initially, bivariate binary logistic regressions were performed between each of the three predictor variables and the high child liking variable for each of the restricted foods and drinks. For multivariable analysis, the three predictors were forced into the model simultaneously and the six covariates were entered by the backward selection method (likelihood ratio) for each of the selected food and drink items. This provided models including just the three predictors together (prediction model) and a series of backward selection models including all three predictors and variations involving the six maternal and child covariates (adjusted models). For all analyses, the final adjusted covariate model presented by the backward selection method was selected and examined for effect size changes in comparison with the prediction model with just the three predictors. Multivariable binary logistic regressions were also performed with the removal of one predictor in turn for all combinations of two predictors to assess confounding between the three predictors. Both bivariate regressions and analyses involving combinations of two predictors were examined for confounding between predictors.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

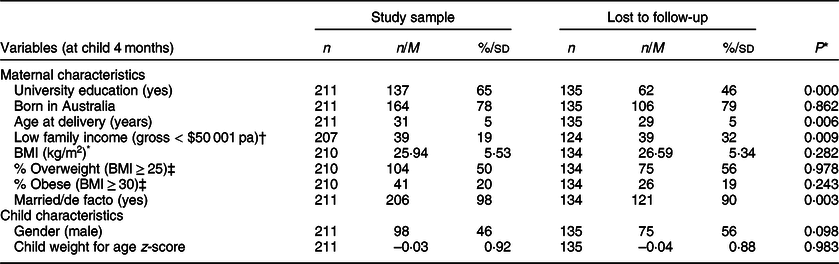

Characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 1. These indicated recruitment and retention bias in comparison with those originally approached to participate in the NOURISH trial but did not proceed(Reference Daniels, Mallan and Battistutta47) and control participants lost to follow-up during the trial by the time children were 5 years old (see Table 1). Participants in the present sample were more likely to be older, university educated, have a spouse and live in a household with a relatively higher income than those who originally provided baseline data and those lost to follow-up.

Table 1 Characteristics of the study sample of mother and child dyads in comparison with the NOURISH trial control participants lost to follow-up

% (valid rounded) within group (count) reported for categorical variables; M (sd) reported for continuous variables.

* For continuous variables, t test, P values and sig. (two-tailed) equal variance assumed. For dichotomous variables, Pearson chi-squared test, P values and sig. (two-sided).

† Original data groups split closest to the lowest quartile.

‡ World Health Organization (WHO)(48).

Descriptive data

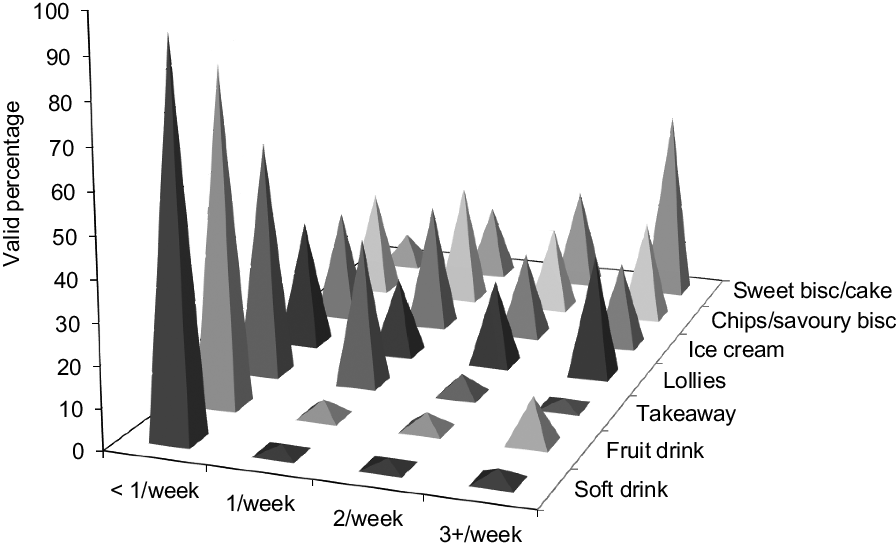

Figure 1 shows children’s weekly intake frequency of selected restricted items at 5 years of age. The intake frequency of sweet drinks was much lower than for the selected sweet foods, with soft drink being the least frequently consumed item of all selected items examined. Takeaway (fast) foods were the least frequently consumed food item, with very few children consuming these foods more than once a week (6 %) at 5 years old. Approximately half of the sample reported their child consumed lollies (sweets), ice cream and chips (crisps)/savoury biscuits once a week or less. Sweet biscuits and cakes were consumed most frequently, with almost half of the sample (48 %) consuming these items three or more times a week.

Fig. 1 Child intake frequency of selected foods and drinks at 5 years

Figure 2 shows mothers’ reports of the percentage of children who had tried a selected restricted food or drink by when they were 14 months, 2 years, 3·7 years and 5 years old. This shows a progressive reduction in total restriction of target foods and drinks as children age but with variation between items. Sweet biscuits and cakes had been introduced to a high proportion of children by the time they reached 14 months (71 % and 66 %, respectively) and more than 50 % of children had tried ice cream and savoury biscuits by this age. A lower proportion of children had tried lollies (sweets) and potato chips (crisps) at 14 months. This markedly increased by the time children were 2 years old and almost all had tried these items by the time children were 3·7 years old. The percentage of children having tried soft drink, fruit drink and fast foods was lowest across all time points, with 26 % of children still not having tried soft drinks by 5 years old and 14 % and 12 % not having tried fast foods and fruit drinks, respectively.

Fig. 2 Percentage of child sample who had tried selected foods and drinks by child aged (![]() ) 14 months, (

) 14 months, (![]() ) 2 years, (

) 2 years, (![]() ) 3·7 years and (

) 3·7 years and (![]() ) 5 years

) 5 years

Multivariable analysis

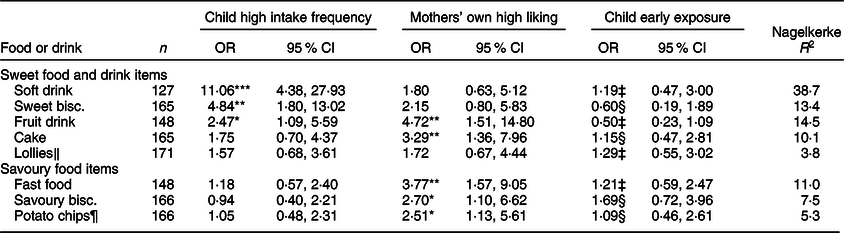

Table 2 displays a summary of multivariable binary logistic regression findings for prediction of child high liking by the three predictors of child high intake frequency, mothers’ high liking and child early exposure, excluding covariates. Inclusion of the maternal and child characteristic covariates in the prediction models did not change the significance of the three key predictors or the order of highest predicted odds. Furthermore, there were no systematic patterns of association between any of the covariates and the outcome measure, child high liking. Confounding between predictors, identified by examining bivariate regressions and combinations of two predictors, has been highlighted in the report of findings that follow. The food item of ice cream was excluded from multivariable analysis due to very high levels of child high liking for this item (94 %).

Table 2 Prediction of child high liking by child high intake frequency, mothers’ own high liking and child early exposure for eight selected restricted food and drink items at child aged 5 years†

*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

† The prediction model includes the three predictors together without maternal and child characteristic covariates.

‡ Child had been exposed to the item by 2 years.

§ Child had been exposed to the item by 14 months.

‖ Sweets (UK).

¶ Crisps (UK).

Child high intake frequency predicted higher odds of child high liking for the sweet foods and drinks examined but did not predict child high liking for any of the savoury foods. Child high intake frequency for soft drink predicted the highest odds for child high liking of all the analyses performed (OR 11·06, 95 % CI 4·38, 27·93, P = 0·001). Furthermore, the total variance explained by the three predictors was much higher than for any other restricted item examined (Nagelkerke R 2 = 38·7) and bivariate analysis suggested this variance was almost totally explained by the child high intake frequency variable. Sweet biscuits were the only other item where child high intake frequency was the highest predictor for child high liking (OR 4·84, 95 % CI 1·80, 13·02, P = 0·002). However, child high intake frequency also predicted significant odds of child high liking for fruit drink (OR 2·47, 95 % CI 1·09, 5·59, P = 0·030) and moderate odds (OR > 1·5) of child high liking for cake and lollies (sweets).

Mothers’ own high liking most commonly predicted the highest odds of child high liking across the range of restricted foods and drinks examined. Mothers’ own high liking predicted the highest and significant odds of child high liking for fruit drink (OR 4·72, 95 % CI 1·51, 14·80, P = 0·008) and cake (OR 3·29, 95 % CI 1·36, 7·96, P = 0·008). Moderate odds were also predicted for the other three sweet items (soft drink, sweet biscuits and lollies (sweets)). Bivariate odds predicted by mothers’ own high liking for soft drink were significant (OR 2·56, 95 % CI 1·06, 6·18, P = 0·036) but confounded by child high intake frequency in the prediction model. Mothers’ own high liking also predicted significant odds of high child liking for all the savoury foods examined (fast foods, OR 3·77, 95 % CI 1·57, 9·05, P = 0·003; savoury biscuits, OR 2·70, 95 % CI 1·10, 6·62, P = 0·030 and chips (crisps), OR 2·51, 95 % CI 1·13, 5·61, P = 0·024).

Child early exposure to the food or drink item predicted fairly low and non-significant odds of child high liking for all the selected foods and drinks examined. Only moderate but non-significant odds were predicted for savoury biscuits (OR 1·69, 95 % CI 0·72, 3·96, P = 0·228). Bivariate analysis showed that child early exposure only predicted significant odds of child high liking for soft drink (OR 3·23, 95 % CI 1·56, 6·68, P = 0·002), which was confounded by child high intake frequency in the prediction model. For all other items, the minimal associations between child early exposure and child liking were not explained by confounding from child high intake frequency or mothers’ own high liking. An unusual finding was the protective associations between child early exposure and child high liking for fruit drink and sweet biscuits in both the bivariate and prediction models. These findings suggested that child early exposure to these items reduces the odds of child high liking at 5 years old, although these findings were not significant.

Variance explained by the three predictors was described using the Nagelkerke’s pseudo-R 2. This varied between items, with soft drinks showing the most variance explained (Nagelkerke R 2 = 38·7) and lollies (sweets) showing minimal variance explained (Nagelkerke R 2 = 3·8) by these predictors for child high liking. Also, lollies (sweets) were the only item examined that did not show a significant association between child high liking and any of the predictors. Potato chips (crisps) showed the lowest variance explained (Nagelkerke R 2 = 5·3) by the three predictors of the savoury foods examined and were the second lowest of all the items examined. This indicated that predictors other than those examined here had a greater influence on child high liking for lollies (sweets) and potato chips (crisps) than for the other items examined.

Discussion

Firstly, this study aimed to examine patterns of descriptive data showing children’s introduction to and current intake of a selection of restricted foods and drinks, and secondly, examine associations between child liking for restricted foods and drinks with current level of restricted child intake, mothers’ own liking and child early exposure to the same restricted foods and drinks. Descriptive data indicated that sweet drinks and fast foods (takeaway) were most highly restricted and sweet biscuits and cakes least restricted. This pattern of variation in restriction of child intake between items was consistent with differential targeting of items by parents reported in a Dutch study by Gubbels et al. (Reference Gubbels, Kremers and Stafleu22). This finding not only suggests that parents may vary levels of restriction between items but also that there may be common patterns of differential targeting among parents. Furthermore, findings suggest that measurement by specific restricted foods and drinks is likely to provide more sensitive measurement of parent restriction than using composite scores of foods and drinks, which has been utilised in cohort studies to date.

The proportion of children who had tried the selected foods and drinks was found to progressively increase with children’s age (14 months, 2 years, 3·7 years and 5 years). This finding is inconsistent with a trend of increasing parent restrictive feeding between 2 and 3·7 years followed by consistency between 3·7 and 5 years found by Daniels et al. (Reference Daniels, Mallan and Nicholson49), using the same NOURISH cohort. Potentially, measurement of parent restriction by the CFQ restriction scale(Reference Birch, Fisher and Grimm-Thomas18) in this study may account for the inconsistency. As suggested earlier and with respect to findings from Holland et al. (Reference Holland, Kolko and Stein21), higher scores on this scale may reflect a greater need for parent restrictive feeding behaviours in response to greater child access to restricted foods rather than a higher level of restriction.

Regression analysis indicated that child high intake frequency of selected sweet foods and drinks at 5 years of age predicted child high liking for the same sweet restricted items (i.e. soft drink, fruit drink, lollies (sweets), cakes and sweet biscuits). This was independently of mothers’ own high liking and child early exposure to the items. However, findings did not show a comparable pattern of results for the savoury foods examined (i.e. fast foods, savoury biscuits and potato chips (crisps)). While further investigation is required to establish whether these findings might be replicated in other samples, Tindell et al. (Reference Tindell, Smith and Pecina50) did find that stimulation of ‘pleasure hotspots’ in the brain (ventral pallidum) of rats showed different responses for repeated consumption of sweet and salty foods. They found that neurological liking responses for salt taste only matched that of sucrose (sugar) when test animals were salt depleted. This suggests that associations between children’s intake and liking for sweet and savoury foods may also vary.

The present study did not provide evidence of an association between low child intake (i.e. higher restriction) and higher child liking for a restricted food or drink. Therefore, the findings of the present study do not support the claims made by short-term restriction experiments, in which restriction of a food increases a child’s desire for the item(Reference Fisher and Birch10–Reference Rollins, Loken and Savage14). The present study’s findings are instead consistent with evidence of an association between child high intake frequency (i.e. low restriction) and child high liking for sweet foods and drinks(Reference Hartvig, Hausner and Wendin26–Reference Sullivan and Birch29).

Regression analysis showed minimal to no association between child early exposure and child high liking for restricted items at 5 years of age, after controlling for the other predictor variables examined. Even bivariate odds only indicated a significant association for soft drink, which was confounded by current child intake frequency. These findings appear to be inconsistent with significant findings by Mallan et al. (Reference Mallan, Fildes and Magarey30) of a bivariate association between children having tried a set of seventeen non-core foods by 14 months and higher mean child liking for these foods at 3·7 years, using the same NOURISH cohort. One explanation for this discrepancy could be that the study by Mallan et al. performed this analysis at a younger child age. Soft drink, which showed a bivariate association in the present study, was also found to be the item most likely to be introduced at a later child age. Therefore, it may be that as children become older and have more frequent access to readily liked restricted foods, earlier exposure becomes less important for child liking. Other reasons could be differences in the foods examined, the use of a composite measure or the larger sample size (n 340) enabling greater potential to detect significant differences in the study by Mallan et al. Further research is required but findings of the present study suggest that if child early exposure influences child liking for palatable restricted foods and drinks, this may be superseded by current intake as children become older.

Mothers’ own high liking for the restricted foods and drinks predicted higher odds of child high liking for the same restricted item at child aged 5 years, which was consistent with other studies examining these associations with a range of different foods(Reference Cooke, Wardle and Gibson31,Reference Falciglia, Pabst and Couch32,Reference Howard, Mallan and Byrne35) . However, the present study also showed that this effect was independent of children’s early exposure and their frequency of intake of restricted items. Mothers’ own high liking was also the only predictor to show an association with child high liking for the savoury foods examined (fast foods, chips (crisps) and savoury biscuits). While heritability may contribute to associations between mother and child liking, studies have indicated that environmental effects are the major contributor to child liking for the high density, sweet and salty foods potentially targeted for restriction(Reference Fildes, van Jaarsveld and Llewellyn33,Reference Breen, Plomin and Wardle34) . Further investigation is required to clarify variables associated with mothers’ own liking for restricted foods and drinks beyond child intake. These may include role modelling(Reference Romero, Epstein and Salvy36,Reference Salvy, Elmo and Nitecki37) , an element of heritability(Reference Fildes, van Jaarsveld and Llewellyn33,Reference Breen, Plomin and Wardle34) and/or types of restrictive feeding practices(Reference Ogden, Reynolds and Smith38,Reference Rollins, Savage and Fisher39) , for example.

Another aspect of restrictive feeding revealed by the present study was that the variance in child high liking explained by the three predictors together (child high intake frequency, mothers’ own high liking and child early exposure) varied between restricted items. This indicated that effects from variables examined in the present study may be more important for predicting child high liking for soft drinks than for lollies (sweets) and potato chips (crisps). Descriptive data also showed an unusual pattern of earlier high restriction of lollies (sweets) and potato chips (crisps) followed by a sharp rise in children’s introduction to these items between child aged 2 and 3·7 years. It may be that social influences, or another variable not examined here, have a greater effect on children’s liking for these items than for the other items examined in these analyses.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study was the examination of both descriptive data patterns and inferential analysis, as well as examination by specific foods and drinks reported to be restricted by a sub-sample of the participants(Reference Jackson43). However, analysis by item increased the number of tests performed and the chance of type 1 error. There were also a number of other limitations. Firstly, the sample included higher proportions of university educated and older mothers, living with a spouse in higher income families than those initially recruited to the NOURISH trial and the population from which the NOURISH sample was selected(Reference Daniels, Mallan and Battistutta47). Secondly, data collected via self-report survey may introduce social desirability bias(Reference Van de Mortel51). Thirdly, the use of secondary data presented limitations in relation to the variables available for analysis. Measures used in this database were not developed specifically for this study and presented some skewed data sets for analyses. Data for child intake of the more highly restricted foods and drinks were highly negatively skewed, and data for child liking were highly positively skewed for most of the items examined, which limited the sensitivity of this analysis. Also, food and drink item categories within the intake and liking scales were not identical. This required some items to be matched, which may have affected results.

Conclusion

This study suggests that restriction of children’s intake of target foods and drinks is reduced as children age and that the level of restriction applied varies between different restricted foods and drinks. Findings also suggested that child intake frequency (level of restriction) and mothers’ own liking for restricted foods and drinks are important dimensions to consider when examining the effects of parent restrictive feeding on children’s liking for restricted foods and drinks. In contrast, early exposure may not be an important predictor of child liking for restricted foods and drinks by the time children have reached 5 years old. The results of this study challenge the belief that limiting children’s intake of foods and drinks high in sugar, fat and/or salt will increase their liking for them. Instead, findings suggest that restricting children’s access to such foods and drinks may be beneficial. It also highlights the importance of current access and that limiting exposure when children are very young is unlikely to assist with reducing later preferences for these highly palatable foods. Furthermore, the findings suggest that mothers should be made aware that their own food preferences may inadvertently influence their child’s liking for restricted foods and drinks. However, further research is required to identify the specific mechanisms mediating this association, such as role modelling, heritability and/or types of restrictive feeding practices applied.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We would like to acknowledge Emeritus Professor Lynne Daniels (QUT), chief investigator on the NOURISH RCT (Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, 426704, APP1021065) for providing access to participant data for recruitment to this study. We would also like to thank the NOURISH families who participated in the study and Ms Lee Jones (QUT) for her advice regarding the statistical analysis for this study. Financial support: Australian Postgraduate Award, K.J. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Authorship: K.J. developed the study design and performed all analyses presented in this manuscript, as well as wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and coordinated revisions. E.J. provided advice on analyses and content of the study, as well as contributed to review of the manuscript. K.M.M. supervised the research process, reviewed data and contributed to review of the manuscript. All authors provided critical revisions and have approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT HREC 00171 Protocol 0700000752) for the NOURISH randomised controlled trial (Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, 426704, APP1021065. Positive feeding practices and food preferences in very young children – an innovative approach to obesity prevention).