Introduction

Viniculture, and agriculture more broadly, was central to elite cultural identity in many ancient Mediterranean societies. As early as the third millennium BC, for example, the Egyptians depicted scenes of wine production in tomb paintings and vinicultural origin myths were embedded in Persian culture (Brun Reference Brun2003). Later, the Roman elite, including the imperial family, became fascinated by the theatre of wine production. This is reflected in ancient literature (e.g. Varro, Pliny the Younger), where farming is also presented in agricultural treatises as an allegory for the upkeep of the state, embodying important ideological and political dimensions (Marzano Reference Marzano, Hollander and Howe2021: 432). It is also attested in art (e.g. vintage scenes on sarcophagi; Dodd Reference Dodd2022: 455–56), and, occasionally, archaeologically in the form of highly elaborate facilities at opulent villas. Wealthy Romans cultivated a luxurious notion of rusticity, romanticising the role of the rural worker and celebrating the landowner as commander of nature. Architecturally, this ideology could be expressed through the fusion of utilitarian and elegant elements to create spaces where production was displayed, observed, flaunted and appreciated. In these ways, agricultural production—and winemaking in particular—played a key role in the construction of elite Roman identity.

Between 1998 and 2018, excavations uncovered a unique and well-preserved Roman winery at the Villa of the Quintilii, on the fifth mile of the Via Appia Antica, south of Rome (Figure 1). The architecture and decorative scheme of this facility are highly unusual, displaying a degree of luxury rarely seen in ancient production spaces. Here, we interpret this remarkable facility for the first time and consider its socio-cultural, economic and historical context, contributing to the study of conspicuous displays of agricultural production by ancient elites.

Figure 1. Villa of the Quintilii general site plan, between the Via Appia Nuova and Antica. The winery building is inset (illustration by M.C.M. s.r.l., modified from Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019, tab. 1).

The only other known comparable villa with a winery decorated to such an elaborate degree is the site of Villa Magna, which lies 50km to the south-east, near Anagni. This facility, and its comprehensive research and excavation history (Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016), forms the foundation from which we discuss the concept of theatrical elite production at the Villa of the Quintilii, its potential connections with ritual, and the ideological relationships of the Roman imperial household with the agricultural domain.

Historical and topographical context

Archaeological investigation at the Villa of the Quintilii can be traced back to the fifteenth century, with records of finds in 1485. It is included on Volpaia's Il Paese di Roma map (1547), and denoted by various local toponyms: first, ‘Statuario’ and, later, ‘Roma Vecchia’ (Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019). Over 600 mostly sculptural artefacts were recovered by Pope Pius VI from the garden and nymphaeum areas and from the front of the basis villae (the artificial platform upon which the villa was built; Figure 1). Systematic excavations began following the purchase of the property by the Torlonia family in 1797, including the discovery, in 1828 or 1829 under Nibby, of a lead fistula (water pipe) naming the Quintilii (indicating ownership by the brothers Sextus Quintilius Condianus and Maximus: Ashby 1910: 4; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019: 18–22).

Occupation on the site dates back to at least the Republican period (Frontoni et al. Reference Frontoni, Galli, Paris, Cecalupo and Erba2020: 237–39), but the first monumental construction is dated by brick stamps to AD 125 (Figure 1; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019: 22). This date aligns with ownership of the villa by the Quintilii brothers (attested on the fistula), who served as consuls of Rome in AD 151. Commodus had the Quintilii killed in AD 182/183 and took possession of their properties, initiating long-term imperial ownership of the villa (Frontoni Reference Frontoni2000). Periodic and extensive restoration, expansion and modification, principally documented by brick stamps, were undertaken between the late second and mid third centuries, during the reigns of Commodus through to at least the Gordians (Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019: 33–36).

Intensive residential occupation of the villa continued through the late third century AD, with the first signs of abandonment not apparent until the fourth or early fifth centuries (Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019: 48). A portrait of the emperor Tacitus (r. AD 275–276) was supposedly placed “in Quintiliorum” (SHA, Tacitus 16.2; Magie Reference Magie1932). While this name may not necessarily indicate this particular property, or that the emperor resided there, a strong imperial connection was probably still maintained at this time (Hedlund Reference Hedlund2008: 133). Sporadic activity continued through late antiquity and the medieval era (Crupi et al. Reference Crupi2018: 424; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019: 33 & 54–55). In all, the monumental villa comprises at least nine construction phases, from foundation c. AD 98–138 through to final activity c. AD 800–1200 (Fichera et al. Reference Fichera2015: 82; see also Ashby Reference Ashby1910; Belfiore et al. Reference Belfiore2016; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019).

The villa, covering 24ha at its largest phase, was built on the Capo di Bove lava flow, a basalt ridge that descends from the Alban Hills towards Rome (Quilici Reference Quilici1974: 15). The commanding panorama offered by this location was surely significant in its selection for the site of the villa, but the fertile volcanic countryside may also have appealed to the Quintilii's agricultural interests (they were the authors of a now-lost agronomical treatise). Indeed, the remains of a second- or first-century BC villa rustica at the seventh kilometre of the Via Appia Nuova, including a treading area and press, illustrate the area's suitability and use for viniculture (De Franceschini 2005: 215–17; Feige Reference Feige2022: 345). Additionally, the Villa of the Quintilii was served by a private aqueduct and three large cisterns (Fichera et al. Reference Fichera2015: 82; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019: 26 & 59–61). This constant supply of water was crucial both for agricultural production and processing at the site, and for residential uses, including the monumental baths.

The discovery and excavation of the winery

The still-mostly buried structures that house the winemaking facility were described by Ashby (Reference Ashby1910: 39) as “badly preserved” and with a slightly different orientation to the villa's other residential buildings. The 1845 Canina map shows these structures as aligned with a feature now known to be a circus (Ricci Reference Ricci1998: 35), the latter comprising an elongated space defined by two long sides with a semi-circular end, used for chariot and horse races, gladiatorial combat and performances (Humphrey Reference Humphrey1986). The structures may also have been visible at the time of Nibby (on the first 1828 ‘Roma Vecchia’ plan) and excavations between 1827 and 1829 may even have taken place within or near this building (Ashby Reference Ashby1910: tab. 3).

Excavations 2017–2018

Archaeological excavations in 2017 and 2018 focused on the investigation of the two parallel curved walls of the circus carceres (starting gates) and towers. Brick stamps and the building technique date these structures to the reign of Commodus (r. AD 177–192). In the search for the second eastern tower, excavation revealed the first evidence for the winery, which had been partially constructed over the demolished tower (Figure 1, inset; Figure 2). Further investigation revealed a large brick-built complex (43 × 25m), which, following abandonment, had been dismantled and the site levelled with mixed construction debris, mortar and ceramics.

Figure 2. Aerial orthophotograph of the Villa of the Quintilii winery building, indicating the treading area (A), press beds (B1 and B2), proposed press mechanism rooms (C1 and C2), collection vat (D), cella vinaria (E), and dining rooms (F1 and F2) (image by M.C.M s.r.l, modified from Frontoni et al. Reference Frontoni, Galli, Paris, Cecalupo and Erba2020: fig. 3).

Winery features and the production process

The complex possesses features typical of a Roman winery (Figures 2 & 3): a grape treading area; two presses; a vat for the collection and settling of grape must; and a system of channels connecting these features to a cella vinaria (wine cellar) with dolia defossa (sunken storage jars; for terminology, see Dodd Reference Dodd2022). Although these features are typical of Roman wineries in several Mediterranean regions, however, their decoration and arrangement are almost unparalleled for a production context in the Roman, and perhaps entire ancient, world.

Figure 3. View from the north-west, with the cella vinaria in the foreground and treading floor and presses behind (photograph by S. Castellani, after Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019: 71).

Treading area

The production process would have begun in the large, 11.5 × 4.5m, rectangular treading area (calcatorium) at the building's southern end (A in Figure 2). It is unlikely that the agricultural workers carried baskets of grapes through the cella vinaria and up the two narrow staircases to reach this area (Figure 5). Instead, access was probably provided by a door or window reached via two large external brick staircases, which lead up to the south side of the treading area. Parallels for this arrangement are known at Villa Regina, Boscoreale, and perhaps Villa Magna (Figure 4; De Caro Reference De Caro1994: 43; Fentress & Maiuro Reference Fentress and Maiuro2011: 346; Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 94–97).

Figure 4. Exterior view of the Villa Magna winery, with the reconstructed window providing direct access to the treading area visible (illustration by D. Booms, after Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 97, fig. 5.34; courtesy of the British School at Rome and E. Fentress).

Figure 5. North-eastern staircase, with marble facing still intact, leading up from the cella vinaria to the treading and press areas (photograph by E. Dodd).

Treading areas are typically lined with cocciopesto (waterproof concrete); here, instead, the area was partially clad in red breccia marble. Marble becomes very slippery when wet and is an impractical choice for hydraulic workspaces (modifications such as hanging ropes and poles were often used to stabilise workers while treading; Brun Reference Brun2003: 53–58). The use of marble, therefore, immediately communicates a sense of the priorities and extreme luxury of this winery.

Mechanical presses

After treading, the pomace or marc—the solid remains of the grapes—would have been placed in baskets made of loosely woven rushes, wound rope, or cloth, or in a wooden framework, and conveyed to the two mechanical presses located to the western and eastern ends of the treading area (B1–B2 in Figure 2). Only the western press bed (ara) is preserved, with its circular channel (canalis rotunda) that would have collected and conveyed the grape must back into the treading area (Figures 2 & 3). The eastern press was found to be badly damaged by modern ploughing.

The western press is of a type that forms part of a distinct mechanical system common across Roman Italy from the second century BC to the fourth and fifth centuries AD (Dodd Reference Dodd2022: 461–68). These presses used one of two lever-and-screw mechanisms, though some may have also utilised winches (Brun Reference Brun2004: 43; Van Limbergen Reference Van Limbergen2019: 112; Dodd Reference Dodd2022: 465–67). At the Villa of the Quintilii, with no evidence of counterweights or anchoring systems preserved, nor the usual stone pier base with mortises (lapis pedicinus/forum) to hold wooden uprights, it is impossible to specify the exact mechanism used. The large wooden lever probably anchored its fulcrum in a niche along the southern wall, as at the villa of Settefinestre (Fentress & Maiuro Reference Fentress and Maiuro2011: 348).

The scale of the surviving press bed (approximately 2m diameter) indicates monumentality and the length of the lever required to work the press surely extended beyond the square press room. While presses were sometimes built on treading areas in Italy, this seems unlikely here, given the dimensions of the space and the symmetrical arrangement of dual presses, whose levers would have crowded the treading area. Instead, the press levers probably extended north over the similarly sized square rooms adjacent to the two narrow staircases (C1–C2 in Figure 2 and visible in Figure 3). These rooms, albeit unexcavated, are also at a lower level—the same as the base of the staircases (Figure 5)—facilitating the downward action of a lever press. In such an arrangement, the levers would have been approximately 8–9m in length. This corresponds with calculations of 6.35–8.8m for levers of this type across Italy (Feige Reference Feige2022: 39–42). The presence of two large lever presses suggests investment in production of a notable scale but also opens the possibility of diverse qualities, including higher quality wine produced solely by treading and lower quality by pressing (see Marzano Reference Marzano, Bowman and Wilson2013; Dodd Reference Dodd2017, Reference Dodd2020a, Reference Dodd2020b, Reference Dodd2020c, Reference Dodd2022). Considering the high-status context of this facility at an imperially owned villa and the possible nature and purpose of production (below), the symmetrical arrangement of these large presses working in harmony likely contributed to the spectacle of production.

Collection/settling vat and distribution system

Cocciopesto-lined channels conveyed the grape must from the mechanical presses back to the treading floor and then through one of three rectangular openings in its northern wall into a large rectangular collection vat also lined with cocciopesto (D in Figure 2). This vat, which allowed impurities and unwanted solid materials in the grape must to settle, may have had several compartments to hold must of different qualities. An impression from a fistula stamp was found pressed into the mortar of this vat; it reads (IM)P GORDIANI ANT[---] (Frontoni et al. Reference Frontoni, Galli, Paris, Cecalupo and Erba2020: 238). This is slightly different from another Gordian fistula stamp, found at the villa in the 1850s by Guidi, which reads IMP M ANTONI GORDIANI AVG I (CIL XV 7339; Ashby Reference Ashby1910: 16).

Once the grape must had filled the collection vat, it flowed through the three central niches, originally fitted with fistulae. Two further niches, one at either end, instead received water from an aqueduct to the south. This nymphaeum-like design, with a scenographic façade consisting of five alternating semi-circular and rectangular niches, would have created a striking fountain effect as the freshly pressed must poured approximately 1m down into the cella area (Figure 3). The water which passed through the two outermost niches was kept separate from the must by masonry stops and channelled back underground, and, at times, may also have served a cleaning function in the facility. The façade, with its niches, was originally clad in white marble veneer, set in cocciopesto and mortar beds, of which small sections of both remain in situ, while other pieces of Africano marble plinth, along with frames of grey and red marble strips, were found in fill layers.

It is difficult to calculate the hydraulic force of these fountains and the mitigation strategies to minimise splashing (and therefore loss) of the grape must. Nonetheless, the system must have been carefully controlled to collect the must in a narrow white marble channel (just over 100mm in width and at least 100mm deep) that ran the length of the façade at ground level. Two further channels of similar dimensions extend perpendicularly from the first channel into the cella vinaria (Figure 3). These two channels run in between each group of dolia defossa and probably continue through the unexcavated northern half of the cella. All three distribution channels are constructed with mortar and lined with white marble veneer of the same type used in the façade of niches.

The cella vinaria

The cella vinaria is positioned in the centre of the winery, with the surrounding rooms focused upon this space (E in Figure 2). Just over half of the cella has been excavated; the arrangement of eight dolia defossa is probably repeated in symmetry to the north-west. A cross-shaped walkway paved with red breccia marble divides the dolia into four groups of two. Short, open marble-lined channels connected each dolium to the distribution network, though only one is preserved (Figure 6). Typical of Roman Italy, the dolia are set into the ground (defossa), which created a stable fermentation microenvironment (see Cheung Reference Cheung2021a; Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Chang and Tibbott2021). All but two of the dolia were removed in antiquity; the remaining examples are in a poor condition, although one rim fragment preserves a stamp reading M*MARII/ PRIMIGENI, datable to the first century AD, between the reigns of Tiberius and Nero (Steinby Reference Steinby1973: pl. LVII.2; Frontoni et al. Reference Frontoni, Galli, Paris, Cecalupo and Erba2020: 238). Evidence for the repair of the dolia was also identified in the form of lead components, including a double dovetail type tie commonly used in the repair of broken dolia (Figure 7; Cheung Reference Cheung, Hochscheid and Russell2021b).

Figure 6. The cella vinaria with dolium rims reinstated in their original positions—only the two in the foreground were found intact and in situ. The one remaining marble channel leading into a dolium is visible at the bottom right (photograph by E. Dodd).

Figure 7. Evidence of dolium rim repair with a lead double dovetail clamp (photograph by E. Dodd).

No tiles or evidence of a roof were identified during the excavations and the cella was probably therefore unroofed; two holes at the centre of the cross-shaped walkway (Figures 2 & 3) might indicate settings for posts to support a cover or velarium (e.g. Villa Magna, see Figure 4: Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 97–98; Villa Regina: De Caro Reference De Caro1994). Once the grape must had been channelled into the dolia, fermentation continued and, later, the aging process began, varying depending on a range of factors, including the intended type of wine (Brun Reference Brun2003: 63–70; Dodd Reference Dodd2020a: 56–59, Reference Dodd2022: 468–72).

Dining rooms

The cella vinaria is surrounded on three sides by rooms that appear to be unrelated to the production process (Figures 1 & 2). On the south-western and north-eastern sides are two identically sized rooms of 9 × 5m (F1–F2 in Figure 2), of which only the former was completely excavated (the third, unexcavated room to the north-west is larger, at 11.5 × 9m). These rooms feature wide entrances, extending almost the entire length of each room, opening directly onto the cella at the same level. Such wide entrances will have provided an expansive view of the interior of the complex and, depending on precise position, allowed glimpses of almost all the production stages (Figure 8). The larger, unexcavated room at the north-western end, if it is of the same design and purpose, will have possessed a commanding longitudinal view of the entire facility (like the banqueting exedra at Villa Magna: Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 90–100, with pls. 5.5 & 5.12). All three rooms were interconnected via the cross-shaped walkway across the cella vinaria and could only be accessed from this central space (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 8. View of the winery from the excavated western dining room with its wide doorway and perspective (photograph by E. Dodd).

The walls and floors of these three rooms, judging from the one room excavated, were richly decorated with an opus sectile (inlaid veneer) motif of carystium (‘cipollino’) marble (53mm thick) circles within two intersecting squares, with strips in carystium marble and red breccia on a white (pavonazzetto) background. This multi-star reticular motif dates to the second and third centuries AD (Frontoni et al. Reference Frontoni, Galli, Paris, Cecalupo and Erba2020: 238). A band approximately 0.20–0.22m wide runs around each motif, with alternating triangles in carystium and portasanta marble, and separation strips in lacedaemonium (serpentino) marble, slate and porphyry.

Discussion

The winery of the Villa of the Quintilii, which conveys a sense of spectacle not normally seen in ancient production spaces, must post-date the reign of Commodus (d. AD 192), as its construction obliterated part of the circus dated to that emperor's reign. At least one phase of the facility dates to the mid third century AD, as evidenced by the Gordian fistula impression and broadly supported by the geometric opus sectile that suggests a date around the late second to early third century. There may also have been an early third-century phase, suggested by the misaligned section of opus sectile in the excavated western dining room (Figure 9). There is no evidence for activity after the Gordian period (Gordian III was deposed in AD 244).

Figure 9. The opus sectile pavement found in the excavated western dining room—misalignment clearly attests two phases of construction (photograph by S. Castellani, after Paris et al. Reference Paris, Frontoni and Galli2019: 72).

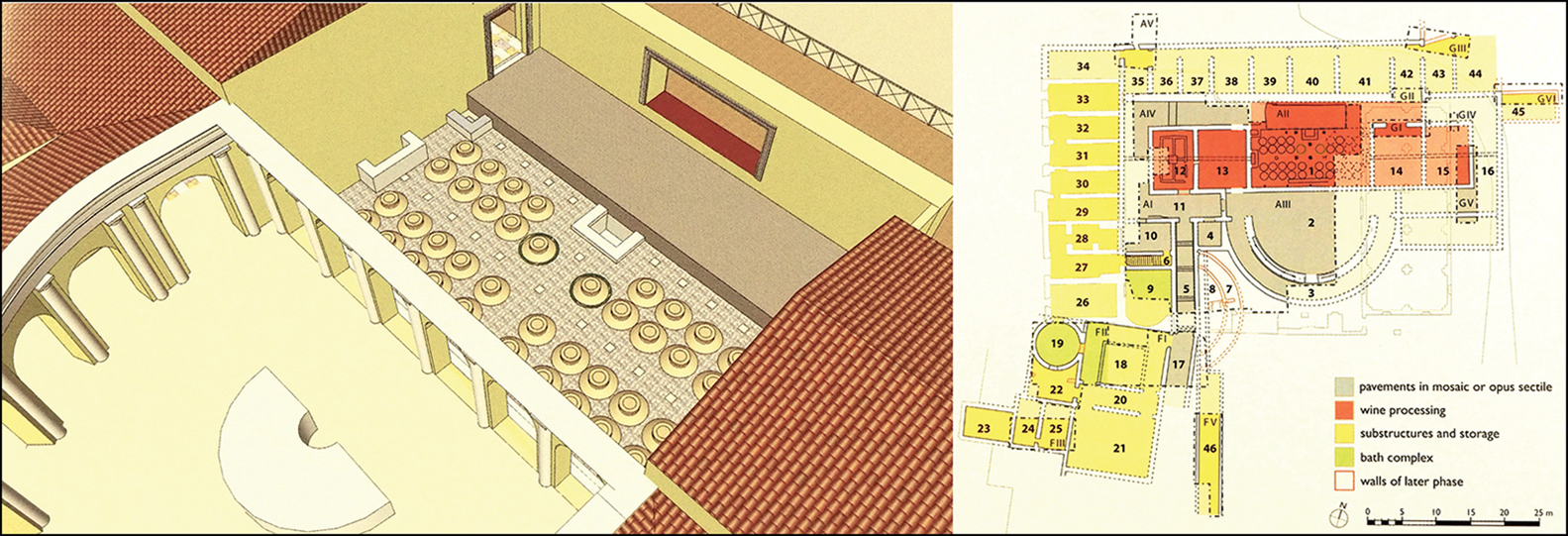

While the theatrical nature of the winery is unparalleled, the complex invites comparison to the lavishly decorated example at Villa Magna (Figure 10). Here, in a similarly opulent imperial context, marble-clad production spaces, including a treading area, distribution system and cella vinaria, were built in the Trajanic-Hadrianic era (early second century AD) and used, with various modifications, into the early third century AD (Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 108–11 & 209). The use of this specific complex in AD 140–145 may be described in Marcus Aurelius's letters to Fronto (Ep. IV.4–6; see trans. by M. Andrews in Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 29–31). Rooms and corridors for the imperial party communicated—audially and visually—with the production spaces, and the letters recount the act of banqueting while watching and listening to the workers treading grapes (Fentress & Maiuro Reference Fentress and Maiuro2011: 344–45). The Villa Magna cella vinaria is larger, with 38 dolia, and paved with a marble opus spicatum (herringbone) floor; the dolia, however, are comparably arranged in pairs (Fentress & Maiuro Reference Fentress and Maiuro2011: 346–47). The treading area at Villa Magna is similarly shaped but slightly smaller (3.54m wide) compared with that at the Villa of the Quintilii (4.5m wide); conversely, the portasanta marble-lined collection vat (one of three at one point in time) at Villa Magna is of an entirely different shape. There are also more auxiliary production rooms at Villa Magna, including one with a quadripartite basin, perhaps to extract must by static pressure (prototropum), and, notably, an absence of presses (Fentress & Maiuro Reference Fentress and Maiuro2011: 351–52; Dodd Reference Dodd2020a: 55). As at the Villa of the Quintilii, all but two of the dolia defossa were removed from Villa Magna, possibly between AD 230 and 250 (Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 209).

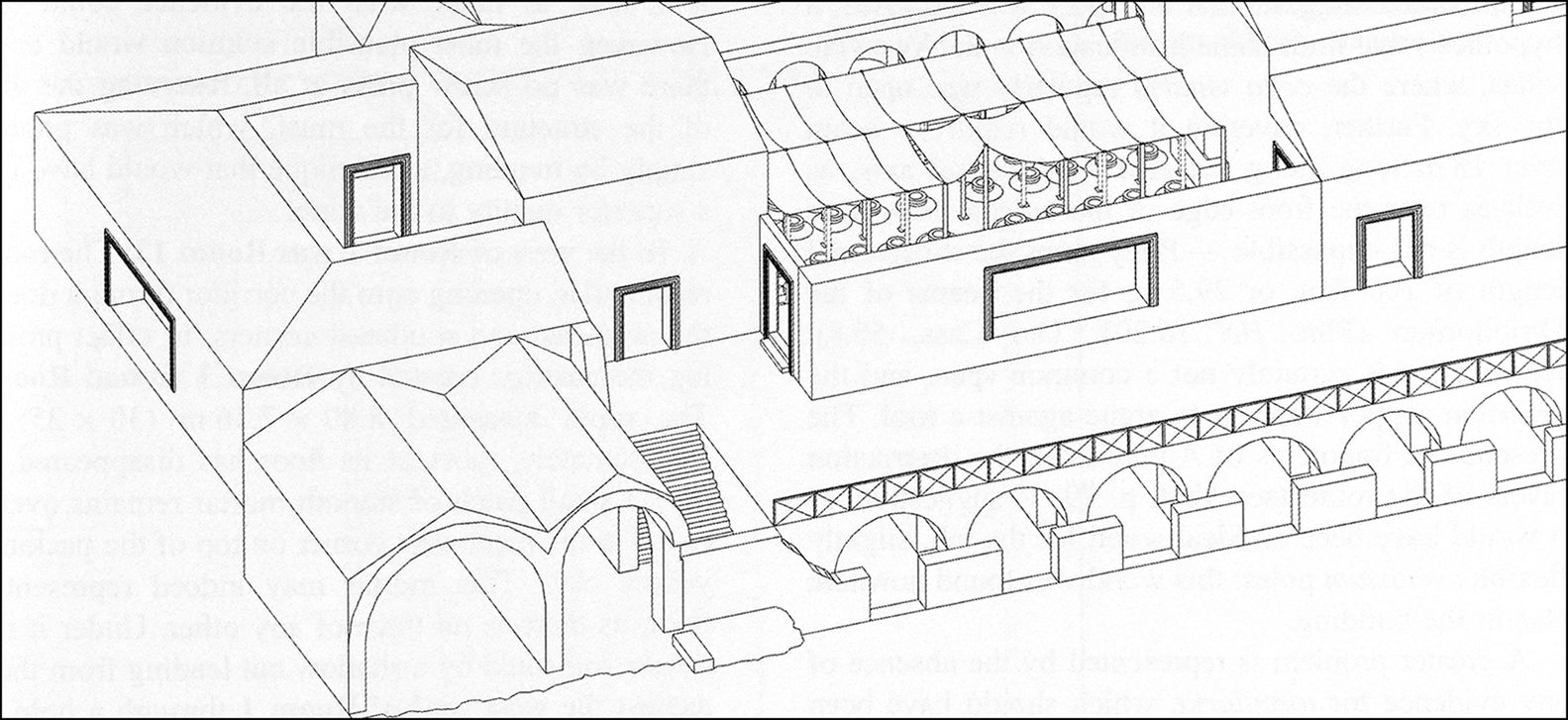

Figure 10. Model (left) and plan (right) of the Villa Magna winery near Anagni, Lazio (illustrations by D. Booms (left) and J. Andrew Dufton (right), after Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: pls. 5.5 & 5.12; courtesy of the British School at Rome and E. Fentress).

This comparison raises several intriguing questions. First, why does Villa Magna—with a smaller treading floor and vat capacity and potentially no mechanical presses—have a cella vinaria more than double the size of that at the Villa of the Quintilii? Second, while speculative, is it possible that dolia removed from Villa Magna in the early to mid third century were transferred to the Villa of the Quintilii to be used in a new imperial winery? The first question interrogates the relationship between production scale and storage capacity. Answering this question is complicated by a multitude of variables, including differences in production styles, region and desired outputs. There is no definitive connection between treading floor size, number of mechanical presses and dolium storage capacity (Baratta Reference Baratta2005; De Franceschini Reference De Franceschini2005; Dodd Reference Dodd2022; Feige Reference Feige2022).

The second question interrogates the relationship between two otherwise unparalleled imperial wineries. Dolia were expensive to commission, time consuming to manufacture, repaired regularly, and transported great distances to be used and reused (Cheung Reference Cheung2021a, Reference Cheung, Hochscheid and Russell2021b; Montana et al. Reference Montana, Randazzo, Barca and Carroll2021; Carroll Reference Carroll2022; Dodd Reference Dodd2022). While cost was surely less of a concern for imperial projects, the fact that dolia from the first century AD were repaired and reused in the cella vinaria of the Villa of the Quintilii 100 years later seems telling (a villa at Somma Vesuviana reused dolia that were at least 200 years old; Aoyagi et al. Reference Aoyagi, Simone, Simone, Marzano and Métraux2018: 150–51). Some of the dolia from Villa Magna were almost certainly reemployed later at that property, as suggested by finds near the sixth century church (Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 196), but this does not negate the possibility that some were also transported 50km north-west towards Rome c. AD 230 for immediate use at the Villa of the Quintilii. Indeed, the imperial patrimonium might have sought to retain property and goods, such as dolia, within its circle (Carroll Reference Carroll2022). This possibility remains hypothetical until archaeometric data, such as ceramic petrography, or stamps suggest otherwise (a new study on the Quintilii dolia by T. Ravasi and M. Carroll is underway).

Some form of continuity between the Villas Magna and Quintilii is also enticing from another perspective. The emperor's role at the former estate was probably more than a representation of elite rusticity, overinvestment, or a “cultured and playful parody of ordinary agriculture” (Purcell Reference Purcell, Cornell and Lomas1995: 155–56). Fentress makes the convincing argument that this was the site of a vintage ritual tied to the ceremonial opening of the harvest in Latium, including public sacrifices, perhaps to Liber Pater or Jupiter, and gatherings elsewhere on the property (Fentress & Maiuro Reference Fentress and Maiuro2011: 357–58; Fentress et al. Reference Fentress2016: 202–208). Extravagant marble decoration marked spaces fit for the emperor and the winery was a ‘theatre’ for this sacred performance. The winery at the Villa of the Quintilii offered a similar marble-clad space for performance, with an elevated, stage-like calcatorium and a cella vinaria situated like a theatre's orchestra, surrounded by dining rooms like a cavea to host onlookers (cf. Figures 3 & 8).

While we lack similar direct literary evidence concerning the Villa of the Quintilii during the reign of Gordian, we might imagine a rearrangement of imperial properties and a relocation of this ritual, still in the heart of Latium, but closer to Rome. This villa, situated on the Via Appia, directly south of Rome, was more visible, convenient and accessible for a more mobile emperor with his large armed retinue (Hedlund Reference Hedlund2008: 133). Equally, however, with no direct evidence it is possible that the theatrical setting held no ritual or religious connection and was simply designed to emphasise the spectacle of agricultural production for an aristocratic audience as part of the construction of elite identity (Nelsestuen Reference Nelsestuen2015, Reference Nelsestuen2016).

The inclusion of two mechanical presses at the Villa of the Quintilii is also notable. The absence of presses at Villa Magna may be explained by the fact that treading produces a higher-quality wine compared with that made by pressing, and hence treading was prioritised in this unique imperial ritual context (Brun Reference Brun2003: 201; Rossiter Reference Rossiter, Lavan, Zanini and Sarantis2008: 98–101; Fentress & Maiuro Reference Fentress and Maiuro2011: 348). Presses might also yet be found in another room or building during further investigations; however, it seems unlikely that the messy, large quantities of pomace were transported very far between treading floor and press. There are few, if any, archaeological examples where the treading floors and presses within a complex are located far apart.

Another feature associated with theatrical production and “competitive self-representation of the elites” is the apsidal room, examples of which are known to frame the demonstration of production at Villa Magna and several other villas in the region (Purcell Reference Purcell, Cornell and Lomas1995: 157 & 169–71; Feige Reference Feige, Haug and Lauritsen2021: 37). Notably, however, the Villa of the Quintilii steers away from this architectural device, instead deploying three rectangular dining rooms to frame the production areas. That to the north had the most privileged view of the production process. As at Villa Magna, installations (e.g. presses, vats, cella) were placed along key visual axes and, in this way, functional elements also served as décor (Feige Reference Feige, Haug and Lauritsen2021: 39). The facility's decorative ensemble, highlighted through the use of luxurious materials, was accentuated further when in use—brightly coloured grape must ran through the thin, white marble channels, drawing the observer's eye up to the façade with its fountains and the treading area above (Figure 3). With the addition of various sounds—workmen joking, laughing or grunting, and the music that accompanied treading (Cerqueira Reference Cerqueira2016)—a truly theatrical impression would have been realised.

Conclusion

The political and military instability of the mid third century AD provides a stimulating historical context for the construction of a ‘theatrical’ winery at the Villa of the Quintilii. The Gordians are traditionally dismissed as having had little impact on the architectural fabric of Rome (Gord. Tres 32.5; Magie Reference Magie1924). Archaeological and epigraphic research is slowly changing this view to recognise that the “brief but … innovative government” of Gordian III began a programme of monumental construction and restoration focused on infrastructure and spectacle (e.g. the Colosseum, baths and fountains; Palombi Reference Palombi2019: 439 & 455). We can now add to this programme an extravagant winery in the Roman suburbium.

Through a combination of decorative, theatrical and inherently functional components, the Villa of the Quintilii winery fuses Varro's—by then ancient—juxtaposition of membra rustica and urbana ornamenta (Res rusticae 3.2.1–18; Hooper Reference Hooper1934). It epitomises how storage facilities could be both utilitarian and elegant in style (contra Vitruvius 6.5.2; Granger Reference Granger1934). The complex also raises tantalising, albeit hypothetical, links to vintage ritual similar to that celebrated at Villa Magna, 50km to the south-east. It seems noteworthy, for example, that, in the four short years that Gordian III was present in Rome, the construction or refurbishment of a lavish imperial winery closer to the city was prioritised.

The Villa of the Quintilii winery provides only the second known example, among what was surely an immense imperial industry, of wine production at an imperial facility (updating Maiuro Reference Maiuro2012: 217). In doing so, it further illuminates the relationship of the imperial domus (household) to the agricultural world. The elite, including the imperial court, leveraged rhetoric and visual spectacle around romanticised agricultural performance to build their self-image within Roman culture and society, illustrating how “ideological goals are inseparable from the business of production” (Purcell Reference Purcell, Cornell and Lomas1995: 167). It may also offer a glimpse into the emperor's annual routine. Compared with other imperial properties, where once-lavish quarters were transformed for utilitarian use, Gordian's imperial court may have regularly visited the Villa of the Quintilii for the annual vintage (Maiuro Reference Maiuro2012; Marzano Reference Marzano, Hollander and Howe2021: 439). This complex also raises broader questions about global antiquity, particularly in other imperial cultures: how, for example, did they engage with ‘rusticity’ across social strata and was there a place for luxurious or theatrical agricultural performance? Although the specific context and form of the Villa of the Quintilii winery was unique, it speaks to the wider nexus of social power and agricultural wealth in the ancient world.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rita Paris, Simone Quilici, Carmelina Ariosto, Sergio Mineo and Clara Spallino of the Archaeological Park of the Via Appia Antica for their support in the excavation and publication of this material. Elizabeth Fentress, Robert Coates-Stephens, Chris Wickham and the anonymous reviewers provided valuable ideas, support and feedback on various stages of this manuscript.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.