Fruits and vegetables (F & V) are important sources of nutrients, dietary fibre and several classes of phytochemicals and are instrumental in disease prevention(1). Studies show that intake of fruits and vegetables is inversely associated with the risk of cancer, heart disease, diabetes, stroke and obesity(Reference Aune, Giovannucci and Boffetta2–Reference Miedema, Petrone and Shikany9). A systematic analysis found that low fruit intake is one of the leading dietary risk factors for death and reduction in disability-adjusted life years in many countries(10). The WHO and the World Cancer Research Fund both recommend fruit and vegetable intake of at least 400 g/d(1). These recommendations are based on studies reporting the fruit and vegetable consumption levels that are associated with reduced risk of disease.

The 2016 Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents recommend daily intakes of 300–500 g of vegetables and 200–350 g of fruit for adults(Reference Chang and Wang11). Despite the benefits described above, much of the Chinese population does not meet these recommended F & V intake levels. According to a 2015 report on nutrition and chronic disease in China, Chinese people consumed an average of 269·4 g of fresh vegetables and 40·7 g of fruit per d in 2012(12).

Research has shown that F & V consumption is linked to other behavioural factors and to individuals’ sociodemographic milieu. F & V consumption has been associated with education, income, age, alcohol consumption and smoking(Reference Dubowitz, Heron and Bird13–Reference Shimotsu, Jones-Webb and Lytle16). One study found differences by socioeconomic status and gender in F & V intake in the USA(Reference Dubowitz, Heron and Bird13). Azagba and Sharaf found lower F & V intake in Canada among adult men compared with women and among smokers compared with non-smokers(Reference Azagba and Sharaf14). An analysis from the USA showed that adults consuming at least five daily servings of F & V were more likely to engage in at least moderate physical activity(Reference Lutfiyya, Chang and Lipsky17). Disparities in F & V intake by sociodemographic and behavioural factors are avoidable, and identification of factors associated with F & V consumption is crucial for increasing F & V intakes. In China, most studies in this area have focused on associations between F & V intake and disease in the general population, but evidence is limited for disadvantaged populations. In this study, we measure associations of sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics with F & V consumption in Chinese adults.

Materials and methods

China Health and Nutrition Survey and study sample

Data used for the study were from the 2015 wave of an ongoing longitudinal survey, the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), conducted by the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The survey was designed as a cohort study using multiple stratified cluster random sampling, with ten survey waves carried out between 1989 and 2015. For the 2015 wave, the survey was conducted in twelve provinces (Guangxi, Guizhou, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Liaoning, Shanxi, Shandong, Yunnan and Zhejiang) and three autonomous cities (Beijing, Chongqing and Shanghai). These twelve provinces and three autonomous cities contained approximately 59·5 % of the population of China.

Sociodemographic factors were collected in 2015 by household survey, individual survey, community survey, dietary measurement and physical examination. Questionnaires were administered by trained field interviewers. The CHNS questionnaire has been used in multiple waves of the study and has been shown to accurately capture usual diet intake. Detailed information on data collection is available in previous publications(Reference Popkin, Du and Zhai18). Diet was assessed by 24-h recalls for three consecutive days and a food inventory. For the food inventory, all food and edible oils, sugar and salt were measured with digital scales every day at the household level. Total household food consumption was estimated by the change in food inventory and waste. Adults were asked to describe all food and beverages consumed over three consecutive days, including food names, amount of food, type of meal and place of consumption. The amounts of individual foods consumed were estimated from the household inventory and the self-reported portion of the dish eaten at home. For the present analysis, total vegetable intake was calculated as the sum of all fresh vegetables eaten, including root vegetables, leguminous vegetables and sprouts, cucurbitaceous and solanaceous vegetables, allium vegetables, stems, leafy and flowering vegetables, aquatic vegetables, tubers and wild vegetables. Total fruit intake was calculated as the sum of all fresh fruits eaten, including kernel fruits, drupe (stone) fruits, berries, citrus fruits, tropical fruits and melons.

The CHNS was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the National Institute for Nutrition and Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (No. 2015017, 18 August 2015). No separate ethics approval was required for this secondary analysis of data from the CHNS.

Outcome variables

The average daily consumption of fresh vegetables and fruits for each adult was calculated as the total amount of fresh vegetables or fruits consumed in 3 d divided by three. We examined the proportion of adults whose average daily fruit or vegetable consumption was equal to or above the cut-offs of 80 g of fruit (one serving) and 320 g of vegetables (four servings). These cut-offs were based on recommendations of the WHO, the World Cancer Research Fund and the 2016 Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents(1,19) . Fruit consumption was much lower than the Chinese recommendation. Accordingly, cut-offs were chosen in order to meet the WHO recommendations and to be as close as possible to the Chinese recommendation.

Sociodemographic and behavioural variables

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, education level, geographic region in China (north or south), type of residence area (city, suburb, town or village, according to administrative divisions) and annual household income. Age was categorised as 18–34, 35–49 or 50–64 years old. Education was categorised as low (≤6 years education), middle (7–12 years education) or high (≥13 years education). Personal annual income was collapsed into tertiles (low, moderate and high).

Behavioural variables examined included occupational physical activity, smoking status and alcohol consumption. Participants were asked to select their occupational physical activity level from a list of options including (1) very light physical activity (working in a sitting position, e.g. office worker, watch repairer), (2) light physical activity (working in standing position, e.g. salesperson, laboratory technician and teacher), (3) moderate physical activity (e.g. student, driver, electrician and metal worker), (4) heavy physical activity (e.g. farmer, dancer, steel worker and athlete) and (5) very heavy physical activity (e.g. loader, logger, miner and stonecutter). Level of occupational physical activity was assessed based on this question and was categorised as highly active (including heavy physical activity and very heavy physical activity), active (moderate physical activity), low activity (light physical activity) and inactive (very light physical activity). Smoking status was categorised as non-smoker, former smoker and current smoker. Alcohol consumption was categorised as non-drinker and drinker (‘drinker’ included both current and former drinkers).

Statistical analysis

F & V intake is expressed as the median with interquartile range (25th to 75th percentiles) due to skewed distributions. Bivariate analysis was used to examine relationship between the consumption of at least 80 g of fruit or 320 g of vegetables and sociodemographic, behavioural and physiological variables using χ 2 tests. While the proportion of adults consuming at least 80 g of fruit per d and those consuming 320 g of vegetables per d are of concern from a public health standpoint, the outcomes were not statistically rare. Accordingly, we used log binomial regression models to estimate crude and adjusted risk ratios (RR) and 95 % CI for associations between explanatory, confounding and outcome variables. CI that did not span 1 indicated statistical significance. All independent variables yielding statistically significant associations with F & V intake in bivariate analyses were included in the log binomial regression models. All statistical analyses for the current study, including calculation of F & V intake, were performed using Stata/se version 14.0. P values reported are two-tailed, and statistical significance was defined as P < 0·05.

Results

The 2015 CHNS included data for 12 226 adults aged 18–64 years. We excluded adults with incomplete or missing data on education (n 35), occupational activity (3), income (277) and smoking (1). This left a sample of 11 910 adults aged 18–64 years included in the present analysis. The distribution of participants across sociodemographic and behavioural variables is shown in Table 1. There were slightly more women than men, and the majority of participants had a low or medium educational level. Participants predominantly resided in villages, and roughly 60% lived in the southern region of China. There was a range of occupational activity levels reported; one-quarter of the sample were current smokers and 30 % were current or former drinkers.

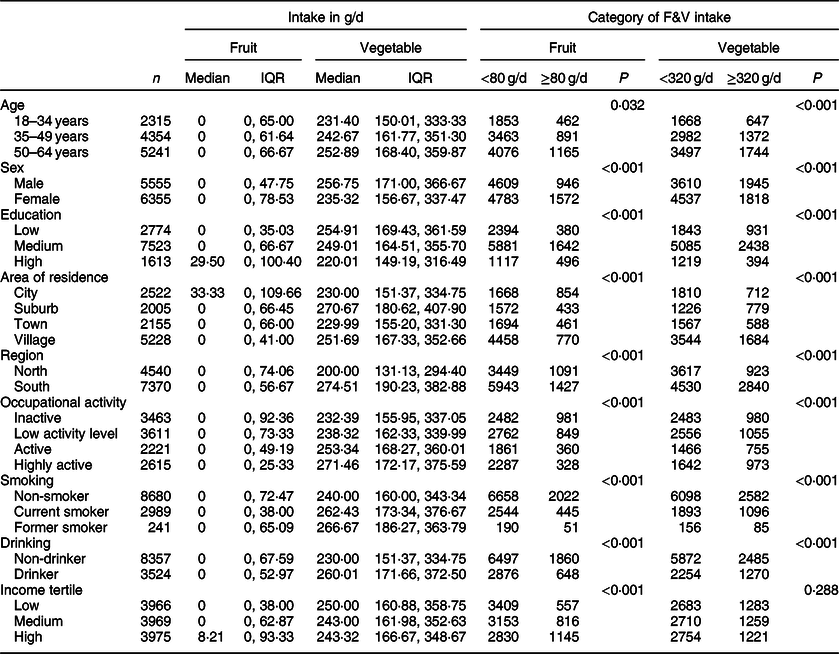

Table 1 Fruit and vegetable intake in relation to sociodemographic and behavioural variables, adults aged 18–64 years, China Health and Nutrition Survey 2015

F & V, fruits and vegetables; IQR, interquartile range.

Differences in the proportion of adults consuming at least 80 g of fruit or 320 g of vegetables were compared using the χ 2 test.

The most frequent vegetable source was stems, leafy and flowering vegetables, followed by cucurbitaceous and solanaceous vegetables, root vegetables, leguminous vegetables and sprouts, allium vegetables, aquatic vegetables, tuber and wild vegetables. The most frequent fruit source was kernel fruits, followed by citrus fruits, tropical fruits, berries, drupe (stone) fruits and melons.

Bivariate analysis

The overall median fruit and vegetable intake levels in the study were 0·00 (interquartile range: 0·00–65·72) and 245·66 (interquartile range: 163·48–352·56) g/d, respectively. Fruit intake of zero was common, with the exception of adults with high education or income levels and those living in a city. The right-hand side of Table 1 shows the proportion of adults consuming at least 80 g v. <80 g of fruit per d and those consuming at least 320 g v. <320 g of vegetables per d. Overall, 21·1 % of adults consumed at last 80 g of fruits per d and 31·6 % consumed at least 320 g of vegetables per d. The proportion of adults consuming at least 80 g of fruit per d and those consuming 320 g of vegetables per d varied significantly in relation to all sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics studied with the exception of personal income, for which significant variation was seen only for fruit consumption. F & V consumption was somewhat higher among older participants. Women consumed more fruits, whereas men consumed more vegetables. Fruit consumption was directly proportional to education level, whereas vegetable consumption was lower in those with higher education levels. The highest fruit consumption levels were found among adults living in cities, whereas the highest vegetable consumption levels were among those living in the southern region. Fruit consumption was higher in the northern region, whereas vegetable consumption was higher in the southern region. Vegetable consumption was highest in adults with high occupational activity levels, whereas fruit consumption varied inversely with occupational activity. Fruit consumption was lowest among current smokers and current and former drinkers, whereas vegetable consumption was higher in current and former smokers and in drinkers than in non-smokers and non-drinkers. Finally, fruit consumption was directly proportional to personal income, whereas vegetable consumption did not vary significantly by income.

Log binomial regression

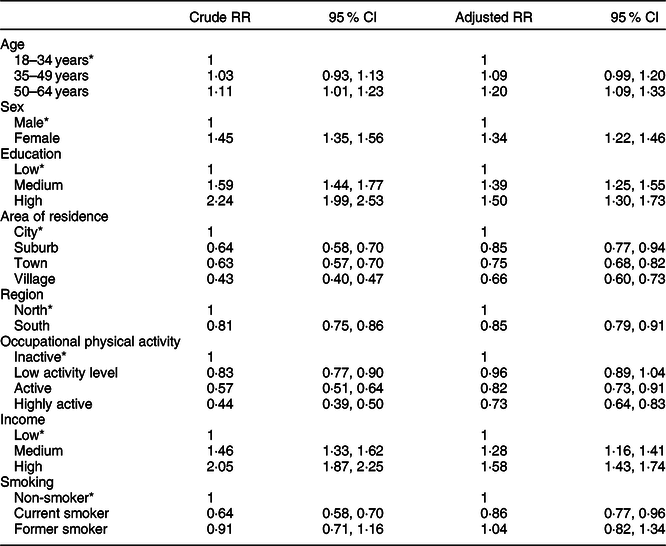

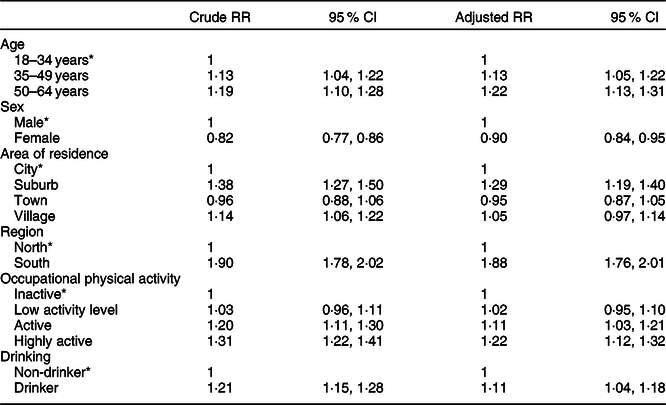

Table 2 displays crude and adjusted RR with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) for associations of sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics with fruit intake. Adults consuming at least 80 g of fruit were more likely to be those aged 50–64 years (RR: 1·20; 95 % CI: 1·09, 1·33), women (RR: 1·34; 95 % CI: 1·22, 1·46), urban residents (the reference group; statistically significant RR for all other areas of residence ranging from 0·66 to 0·85), those in the northern region (reference group; RR for southern region: 0·85; 95 % CI: 0·79, 0·91), those who were physically inactive (reference group; statistically significant RR for other groups ranging from 0·73 to 0·82), those with medium (RR: 1·28; 95 % CI: 1·16, 1·41) or high income (RR: 1·58; 95 % CI: 1·43, 1·74) levels and non-smokers (reference group; RR for current smokers: 0·86; 95 % CI: 0·77, 0·96). Table 3 shows results of log binomial regression for vegetable consumption. Adults consuming at least 320 g of vegetable daily were more likely to be those aged 35 years and up (statistically significant RR ranging from 1·13 to 1·22), men (RR for women: 0·90; 95 % CI: 0·84, 0·95), suburban residents (RR: 1·29; 95 % CI: 1·19, 1·40), those in the southern region (RR: 1·88; 95 % CI: 1·76, 2·01), those with active (RR: 1·11; 95 % CI: 1·03, 1·21) or high (RR: 1·22; 95 % CI:1·12, 1·32) occupational activity levels and current or former drinkers (RR: 1·11; 95 % CI: 1·04, 1·18).

Table 2 Log binomial regression results, factors associated with fruit intake of at least 80 g/d among adults aged 18–64 years, China Health and Nutrition Survey 2015

RR, risk ratio.

* Reference category.

Table 3 Log binomial regression results, factors associated with vegetable intake of at least 320 g/d among adults aged 18–64 years, China Health and Nutrition Survey 2015

RR, risk ratio.

* Reference category.

Discussion

In this study of adults in China, we found that only about one-fifth of adults met the recommended fruit consumption levels, and about one-third met the recommended level for vegetable consumption. We also found associations between numerous sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics and F & V intake. Fruit consumption was lower among males, younger adults, those with lower incomes and education levels, those living in villages and in southern China, smokers and those with higher occupational activity levels. Vegetable consumption was found to be lower among younger adults, women, adults living in cities and in northern China, those with lower occupational physical activity levels and non-drinkers.

Results from our study are consistent with previous findings from Canada and the USA showing that people with higher education and income levels had significantly higher fruit intake(Reference Azagba and Sharaf14,Reference Drewnowski and Rehm20,Reference Rehm, Penalvo and Afshin21) . Findings in our study regarding fruit intake may be due in part to the cost of fruit in China, which is high. In addition, education level may be associated with fruit consumption through dietary knowledge. In contrast, we did not find a significant relationship between income and vegetable intake. This result may reflect the important role played in Chinese diets by vegetables, which are commonly used in dishes at every meal. In ancient China, it was recommended that diet should be close to nature, and vegetables were thought of as being preferable to meat. In winter, Chinese cabbage remains one of the most frequently consumed dishes in northern China today, and it is used in dozens of dishes in this region. Cultural factors and traditions have been found to be significantly related to F & V consumption(Reference Azagba and Sharaf14,Reference Pollard, Kirk and Cade15) . Despite the lack of an observed economic gradient, only one-third of adults met vegetable intake recommendations. Accordingly, efforts are needed to increase vegetable consumption across the economic spectrum in China.

We found that men tended to have higher vegetable intakes than women, whereas fruit intakes were higher among women. Our results regarding gender and fruit intake concur with studies from Canada, Germany and the USA finding that females had higher fruit intakes than males(Reference Azagba and Sharaf14,Reference Lee-Kwan, Moore and Blanck22,Reference Heuer, Krems and Moon23) . However, our results regarding gender and vegetable intake contrast with the findings of these studies. The difference in results between our study and previous research regarding F & V intake in relation to gender may be partly due to higher overall knowledge regarding F & V consumption among women compared with men, a pattern that has been observed in China as well as in other countries(Reference Hu, Gou and Shi24,Reference Baker and Wardle25) . Alternatively, the frequent consumption of fruit as a snack in China may lead to disparities in fruit intake between men and women, as gender differences in lifestyles may entail differing eating schedules and habits. With China’s rapid socioeconomics changes, lifestyles and consumption patterns have greatly improved for women. In addition, it has been shown that women in China spend more than men on personal health and fitness(Reference Yu26). Finally, women in China have higher levels of health literacy compared with men, including health knowledge, lifestyle, behaviours and health-related skills(Reference Yinghua, Qunan and Qi27).

Our study found that adults who live in southern China and those who live in suburbs, villages and town settings were less likely to consume the recommended amount of fruit. This finding is similar to those from the China Kadoorie Biobank project, in which adults living in cities had higher fruit intakes than those living in villages(Reference Chenxil, Canqing and Huaidon28). This pattern may stem in part from the cost and accessibility of fruit(Reference Rehm, Monsivais and Drewnowski29). Adults living in suburbs, villages and town areas tend to be poorer than those in cities and are served by fewer stores offering lower-cost foods(Reference Miller, Yusuf and Chow30). Our findings regarding fruit consumption in relation to area of residence point to a need for targeted interventions to improve fruit intake in disadvantaged groups in China, especially individuals living in villages. The climate in southern China is generally warm and humid, with long periods of sunshine, and is thus especially suitable for planting F & V. In contrast, the climate in the north is characterised by four distinct seasons, with high temperatures and rain in the summer and cold and dry conditions in the winter. The south is thus more suitable for growing F & V than the north. Our study found factors associated with fruit intakes beyond natural conditions. It is not clear why we observed higher fruit intakes in the north yet higher vegetable intakes in the south. Accordingly, we recommend that future studies include more detailed exploration of geographic variation in F & V intake in China.

Our findings that adults in the youngest age group (18–34 years old) consumed the lowest levels of fruits and vegetables are in agreement with previous reports from the USA and Australia(Reference Drewnowski and Rehm20,Reference Lee-Kwan, Moore and Blanck22,Reference Chapman, Goldsbury and Watson31) , suggesting that elderly adults may be able to make healthier food choices than younger adults. While our findings indicate a need to promote adequate fruit and vegetable intake to the youngest age group, the reasons for variation in diet by age are not clear. Young adults frequently experience more flux and change over time in their daily lives than do older adults, and this is likely to affect their overall diet quality(Reference Nelson, Story and Larson32). We recommend that future studies explore dietary patterns in relation to other psychosocial risk factors and lifestyle changes in young adults.

Adults in our study with moderate to high levels of occupational physical activity consumed less fruit but more vegetables than those with lower occupational activity levels. Our measurement of occupational physical activity was centred on activities during working hours, grouped by occupation. Accordingly, our finding of lower fruit consumption among those with lower occupational physical activity levels may partly reflect residual confounding from income and other occupation-related factors(Reference Pollard, Kirk and Cade15). One study from the USA found that adults living in rural areas who engaged in at least moderate physical activity were more likely to consume five servings of F & V, echoing our findings for vegetable intake but not fruit intake(Reference Lutfiyya, Chang and Lipsky17). Consistent with other studies, we found that smokers consumed less fruit than non-smokers(Reference Vieira, Abar and Vingeliene8,Reference Affret, Severi and Dow33) . These results suggest that non-smokers may make healthier food choices than smokers. However, we also found that drinkers consumed more vegetables than non-drinkers, a result that is inconsistent with previous studies(Reference Myint, Welch and Bingham34), suggesting that certain patterns of vegetable consumption in relation to alcohol use may be specific to China. Additional research is required to understand factors influencing the relationship between alcohol intake and diet in China.

Finally, we found that more adults in China adhere to recommendations for vegetable intake than for fruit intake. Again, factors associated with vegetable intake show patterns that may be unique to China. Our findings suggest that further dietary policies and interventions are needed in China and that fruits and vegetables must be considered separately rather than simply focusing on overall diet quality.

Several limitations to our study must be acknowledged. First, the sample was taken from an ongoing cohort study that may not reflect the overall adult population in China. The CHNS sample was randomly selected using a sampling strategy aimed at capturing a range of economic and demographic circumstances(Reference Popkin, Du and Zhai18). The twelve provinces and three autonomous cities sampled for the 2015 CHNS contained approximately half the population of China. Furthermore, the proportions of adults meeting minimum F & V intake recommendations were similar to those reported by China National Nutrition and Health Surveillance and the China National Nutrition and Health Survey(Reference Chang and Wang11,Reference He, Zhao and Yu35) . Second, F & V consumption patterns vary by season, and we did not account for seasonality in our analyses. This may have led to inaccurate estimation of overall F & V intake, though it is not likely to have created spurious associations with sociodemographic and behavioural factors. Third, this study is cross-sectional and cannot assess causality, including reverse causality. We recommend that future studies of dietary patterns in China assess the effects on F & V intake of geographic mobility, educational and economic opportunities, uptake of public health interventions related to smoking and alcohol consumption and changes in occupational activity levels.

Conclusions

In this study, based on data from a national survey in China, we found that age, sex, area of residence, region and occupational activity were all associated with F & V intake. This study helps identify nutritional problems in relation to sociodemographic and behavioural factors and suggests that further nutrition intervention programmes for adults are needed in China.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: This research uses data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS). The authors thank the team at National Institute for Nutrition and Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the fifteen provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Financial support: The authors thank the National Institute for Nutrition and Health, the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the Carolina Population Center (P2C HD050924, T32 HD007168), the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the NIH (R01-HD30880, DK056350, R24 HD050924 and R01-HD38700) and the NIH Fogarty International Center (D43 TW009077, D43 TW007709) for financial support for the CHNS data collection and analysis files from 1989 to 2015 and later surveys, and 2015 Chinese Nutrition Society (CNS) Nutrition Research Foundation—DSM Research Fund (No. CNS2015075B) for 2015 survey. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: L.L. and B.Z. contributed to the initial design of the analysis; L.L. conducted the analysis and wrote the manuscript; Y.F.O.Y., H.J.W., F.F.H., Y.W., J.G.Z., C.S., W.W.D., X.F.J., H.R.J. and Z.H.W. contributed to collect the data and reviewed the manuscript and B.Z. revised the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute for Nutrition and Health (no. 2015017, 18 August 2015). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.