The prevention and treatment of the high prevalence mental disorders, depression and anxiety are of increasing global importance due to the substantial health, social and economic burden they impose. Major depressive disorders and anxiety disorders are among the leading causes of years lived with disability( Reference Vos, Flaxman and Naghavi 1 ); in 2010, the global cost of these conditions was estimated to be $US 2·5 trillion( Reference Bloom, Cafiero and Jane-Llopis 2 ). Although pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are considered first-line treatments for depression, fewer than half of those treated achieve remission( Reference Casacalenda, Perry and Looper 3 ). Thus, there is a need to develop further strategies to effectively treat depression.

Over recent years, evidence has emerged to support a relationship between habitual diet quality and the risk for depression. Epidemiological studies have suggested that a healthy dietary pattern including fruits, vegetables, fish, olive oil, nuts and legumes is protective against depression( Reference Sanhueza, Ryan and Foxcroft 4 , Reference Sanchez-Villegas and Martinez-Gonzalez 5 ). Conversely, a dietary pattern that comprises a high consumption of processed foods and sugary products may increase the risk of depression( Reference Sanhueza, Ryan and Foxcroft 4 , Reference Akbaraly, Brunner and Ferrie 6 ). While the observational evidence generated to date is suggestive of a relationship between dietary intake and depression, only randomised controlled trials (RCT) that elucidate the effects of dietary change on mental health outcomes can verify whether the relationship between diet and mental health is causal in nature.

Previously, intervention studies evaluating the role of dietary improvement on disease outcomes have been conducted in populations with (somatic) chronic illnesses rather than mental disorders, largely focusing on those: overweight and obese; with elevated risk factors for metabolic disorders; with other medical illnesses; in the general population. These studies have often employed metabolic primary end points including obesity and risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and CVD. Further, there has been wide variance in the mode of delivery and theoretical models underpinning these interventions. Those interventions successful in achieving dietary behaviour change and compliance have been characterised by the provision of written information (e.g. dietary guidelines, shopping lists, meal plans and recipes), free provision of key food items, self-monitoring, goal setting, individual contracts, group sessions( Reference Zazpe, Sanchez-Tainta and Estruch 7 ) and dietary counselling (e.g. motivational interviewing and mindfulness)( Reference Framson, Kristal and Schenk 8 ). In some instances, frequent contact during intensive interventions has been shown to be beneficial( Reference Zazpe, Sanchez-Tainta and Estruch 7 ).

Indeed, the existing evidence base provides support for physical health benefits as a result of dietary interventions and it stands to reason that these effects may extend beyond physical benefits to impact upon mental health outcomes. However, the impact of dietary improvement on mental health currently remains unclear.

The purpose of the present systematic review was thus to synthesise data from existing RCT of dietary interventions (with a whole-of-diet approach) that have investigated depression and/or anxiety outcomes (as either primary or secondary outcomes) in psychiatric and other populations. Furthermore, we sought to determine which components of dietary interventions (e.g. interventionist, mode of delivery, session frequency) are associated with programme success. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review of its kind.

Methods

Literature search

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 9 ) were used as a methodological template for this review. Please see online supplementary material 1 for the PRISMA checklist.

Relevant studies were identified by systematic search from the Cochrane, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PubMed and PsycInfo databases for articles published between April 1971 and May 2014. Relevant keywords relating to diet in combination as MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) terms and text words (‘diet’ or ‘Mediterranean diet’ or ‘diet therapy’ or ‘diet education’ or ‘diet counselling’ or ‘diet intervention’ or diet ‘treatment’ and their variants) were used in combination with words relating to depression and anxiety (‘anxiety’ or ‘anxiety disorder’ or ‘depression’ or ‘depressive disorder’ or ‘major depressive disorder’) and intervention styles (‘randomised controlled trial’ or ‘random allocation’ or ‘clinical trial’ or ‘control groups’ and their variants). The search was limited to studies written in the English language and undertaken in human subjects. Additional publications were identified from references published in the original papers. Please see online supplementary material 2, Supplemental Table 1 for the full electronic search strategy.

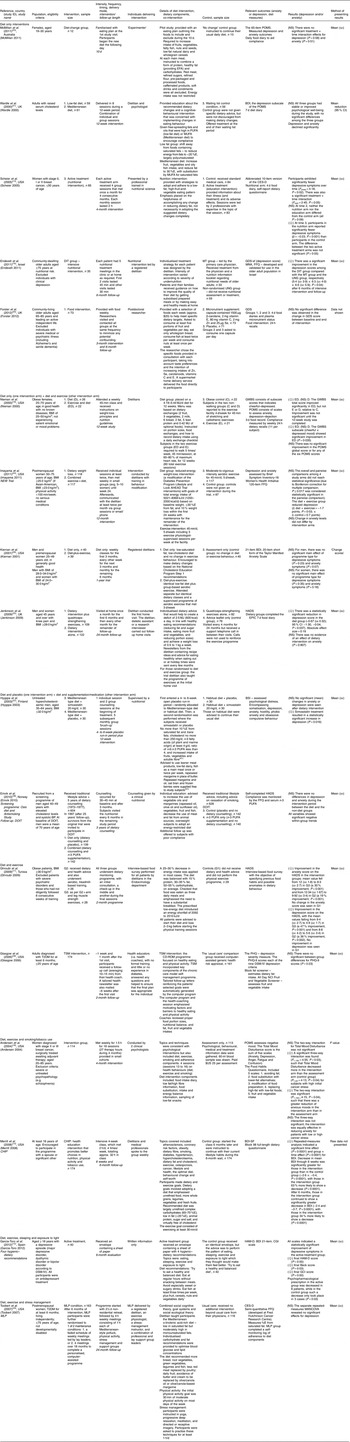

Table 1 Characteristics and results of diet interventions, categorised by composite interventions

DOIT, The Diet and Omega-3 Intervention Trial; CHIP, Coronary Health Improvement Project; MLP, Mediterranean Lifestyle Program; BP, blood pressure; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; DIT, dietary intensive treatment; TSM, tailored self-management; EFA, essential fatty acids; %E, percentage of total daily energy intake; CD-ROM, compact disk – read only memory; MT, medical treatment; UNG, untreated nutrition group; POMS, Profile of Mood States; BDI, Beck depression Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; GDS-sf, Geriatric Depression Screening Scale; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GWBS, General Well-Being Schedule; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire nine-item scale; NCI, National Cancer Institute; BDI-SF, Beck Depression Inventory – Short Form; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression seventeen-item scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression scale; MANCOVA, multivariate ANCOVA.

Eligibility criteria

All articles that evaluated diet as a whole were included; studies which evaluated single food items or nutrients or meal replacement products (e.g. liquid shakes) were excluded. In order to be eligible for inclusion, the dietary intervention needed to be described in sufficient detail, highlighting the main components of the diet.

Only RCT were considered for inclusion, including a dietary intervention v. a control condition (e.g. usual (standard) care, non-dietary modification). Dietary studies with combined interventions (e.g. exercise, stress management) were eligible, as were dietary studies that included a placebo control. Composite interventions (e.g. those that use diet as a component of a multifaceted intervention) were also included. Where a study employed a multiple-treatment-arm design (e.g. diet and exercise v. diet), the results from the condition considered most comparable to other studies were selected.

Only studies that included adults (≥18 years of age) and reported validated depression or anxiety outcome measures were eligible for inclusion. Studies were not deemed ineligible if they included those with a chronic condition (e.g. CVD, T2DM, cancer, hypertension); however, those comprising participants with eating disorders or pregnant and breast-feeding women were excluded as these conditions were considered to be potentially confounding factors.

Data extraction

We screened potentially relevant articles for eligibility based on titles and abstracts. If deemed potentially eligible, the full text publication was retrieved and reviewed (R.S.O., S.D.). Where areas of uncertainty occurred co-authors were consulted (C.I., F.N.J.). To prevent duplication and allow for unique analysis, only empirical studies were included in the present review (e.g. systematic reviews were not included). Data were extracted from included studies and details are presented in Tables 1 and 2, using the following parameters: study aims, study design, study location, sample size, participant characteristics, length of follow-up, programme components (dietary and co-interventions), control group protocol, research outcomes and results.

Table 2 Study aims, primary and secondary outcomes of included studies

BP, blood pressure; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; POMS, Profile of Mood States; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; QOL, quality of life; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression seventeen-item scale; GDS-sf, Geriatric Depression Screening Scale; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; WOMAC, Western Ontario McMaster osteoarthritis index; SF-36, Short Form (36) Health Survey; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire nine-item scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression scale; TSM, tailored self-management; CHIP, Coronary Health Improvement Project.

* Power calculation not reported in article.

† Did not reach statistical significance due to inadequate sample size.

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest (depression and anxiety) were those measured by validated self-report inventories, psychiatric diagnostic interview or medical records. Instruments containing a subscale from which a depression/anxiety score could be derived were eligible for inclusion.

Synthesis of results

Studies were classified into three categories in relation to their results:

-

1. those with statistically significant improvements in depression/anxiety outcomes, compared with the comparator group (☺);

-

2. those with non-significant improvements in depression/anxiety outcomes, compared with the comparator group (NS); and

-

3. those with significantly worse scores, compared with the comparator group (☹).

In order to assess which programme components led to improved outcomes, a table was created to classify dietary interventions by the method of intervention delivery (four categories), interventionist (five categories), dietary components (three categories) and weight and exercise focus (two categories).

Quality assessment

Quality criteria recommended by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (formerly the American Dietetic Association) were used to assess the quality of the included studies( 10 ). This tool includes criteria for assessing selection bias, allocation bias, blinding, data collection, study retention, intervention adherence and methods of handling withdrawals/dropouts. Each study was assessed as negative, neutral or positive using the ‘most important quality consideration’ questions listed in Table 3·2a of the ADA Evidence Analysis Manual to assess the quality of RCT( 10 ). All studies were included in the review regardless of quality rating. This information was used as a post hoc way of synthesising the data from high-quality studies. All studies received a score out of 12. A score of 9 or above was considered positive (+), indicating that it clearly addressed issues of inclusion/exclusion, generalisability, bias, data collection and analysis. A score of 6–8 was considered neutral (ϕ) (neither exceptionally strong nor weak). A score of 5 or below was negative (−), reflecting that these issues were not reported or addressed adequately.

Results

Study selection

The initial search yielded 1274 citations, of which 1194 were excluded upon initial screening for not meeting inclusion criteria. Of the remaining eighty articles, sixty-five were excluded for the following reasons: not a target population (e.g. bulimia nervosa; n 2); did not include a target outcome (n 11); not a relevant intervention (e.g. not a whole-of-diet approach; n 11); not a target study design (e.g. study protocol or not an RCT; n 14); control group was not usual care or non-dietary modification (n 20); insufficient detail of dietary intervention (n 6); and not a validated measure of anxiety (n 1). Fifteen studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and an additional four studies were found through searching of the included studies’ reference lists (n 3) and forward citation (n 1). Two studies( Reference Thieszen, Merrill and Aldana 11 , Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 12 ) are not discussed separately in the present paper as they report on the same cohort and intervention as two other studies( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 , Reference Merrill, Taylor and Aldana 14 ) already included in the systematic review. Overall, seventeen RCT were included in the review. Study selection and extraction process are according to PRISMA guidelines( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 9 ). Figure 1 displays the results of study selection.

Fig. 1 The process of study selection and the number of included and excluded studies; articles were published between April 1971 and May 2014

Study characteristics

Location and sample size

The majority of studies were conducted in the USA (n 8). Three studies were conducted in the UK and one each in Australia, Finland, Israel, Norway, Spain and Tunisia. Seventeen studies were included in the final analysis, representing a total of 4015 subjects, with sample sizes ranging from twenty-five to 563.

Population characteristics

Only one study exclusively targeted adults with a depressive episode( Reference Garcia-Toro, Ibarra and Gili 15 ). Five studies targeted individuals with a chronic disease (e.g. high cholesterol, high blood pressure, T2DM), three studies targeted overweight or obese individuals and two studies targeted women with breast cancer. Five studies recruited women only and two studies recruited only men. With regard to co-morbid psychopathology, five studies( Reference Endevelt, Lemberger and Bregman 16 – Reference Forster, Powers and Foulds 20 ) excluded individuals with clinical depression or severe psychiatric disorders (e.g. schizophrenia) or individuals experiencing emotional or mood problems. Table 1 provides further detail of the eligibility criteria and participant characteristics for each study.

Study aims and primary outcomes

Primary outcomes varied among studies. Only four studies reported being powered to detect statistically significant differences in depression and/or anxiety scores( Reference Garcia-Toro, Ibarra and Gili 15 , Reference Andersen, Farrar and Golden-Kreutz 18 , Reference Wardle, Rogers and Judd 21 , Reference Hyyppa, Kronholm and Virtanen 22 ). A further seven studies included a depression and/or anxiety score as a primary end point; however, information as to whether the study was sufficiently powered was lacking (Table 2).

Intervention description

Programme intensity (sessions offered and length of follow-up)

There was considerable diversity in programme intensity. The number of dietary intervention sessions offered ranged from one to sixty-two sessions. Length of follow-up ranged from 10 d to 36 months with the most common length of follow-up being 6 months (n 4) and 3 months (n 3).

Intervention style and programme components

The majority of studies (n 6) delivered the intervention in a group setting, followed by individualised education/treatment (n 4) or as a combination of individual and group sessions (n 3). Other intervention styles included written recommendations (n 1), CD-ROM (compact disk – read only memory) programme and telephone call (n 1) and non-residential retreat and group meetings with/without a personalised computer-assisted program (n 1). One study( Reference McMillan, Owen and Kras 23 ) failed to report the intervention delivery method.

Five studies( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 , Reference Endevelt, Lemberger and Bregman 16 , Reference Forster, Powers and Foulds 20 , Reference Wardle, Rogers and Judd 21 , Reference McMillan, Owen and Kras 23 ) delivered the intervention with a diet only focus. A further four studies( Reference Nieman, Custer and Butterworth 19 , Reference Imayama, Alfano and Kong 24 – Reference Kiernan, King and Stefanick 26 ) included two intervention arms: a diet only arm and a diet and exercise arm. The remaining eight studies included programme components in addition to dietary improvement, including: physical activity/exercise (n 2); physical activity/exercise and education on smoking/tobacco use (n 2); physical activity and stress management, e.g. yoga and meditation (n 1); placebo or n-3 PUFA supplementation (n 1); placebo or cholesterol-lowering medication (simvastatin; n 1); and sleeping, exercise and exposure to light (n 1).

All studies used a whole-of-diet approach. Common dietary themes included increasing fruit, vegetable and fibre intake (n 13) and an increased fish intake (n 7). Approximately 41 % of studies made a specific recommendation to reduce intake of red meat, to select leaner meat products or to follow a low-cholesterol diet, while ~59 % of studies had a weight-loss focus or reported on weight change.

The majority of studies (n 9) used a dietitian for the dietary intervention. This was achieved using a dietitian in isolation (n 5) or a dietitian working with another practitioner, such as: dietitian and dietetic assistant/research interviewer (n 1); dietitian and medical professionals (n 1); dietitian and exercise physiologist and stress-managing instructor and group leaders (n 1); and dietitian and psychologist (n 1).

The remaining studies used clinical psychologists (n 1); a postdoctoral researcher (n 1); professionals trained in nutritional science (n 1); nutritionists (with no evidence of dietitian qualifications) (n 2); a lay person, e.g. health coach with no formal training (n 1); or an ‘experimenter’ (n 1). Only one study used written recommendations only and did not report on the qualifications of the individual who developed the guidelines( Reference Garcia-Toro, Ibarra and Gili 15 ).

Depression and anxiety outcome measures

The depression and anxiety outcomes reported among the studies were as follows: Profile of Mood States (POMS); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Geriatric Depression Screening scale (GDS); Hamilton Depression scale (HAM-D); Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); Clinical Global Impression scale; Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ); Brief Symptom Inventory; Taylor Manifest Anxiety scale; General Well-Being Schedule (GWBS); and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

All studies included a depression outcome. The most common depression and anxiety outcome measures used were the POMS (n 4), the BDI (n 4)( Reference Wardle, Rogers and Judd 21 ) and the HADS (n 3)( Reference Zigmond and Snaith 27 ) (Table 1).

Results of individual studies

Depression and anxiety outcomes are presented separately for each paper due to the heterogeneity of included studies. These outcome measures are presented as differences in mean values from baseline scores. The heterogeneity across exposures, outcome measures and intervention period precluded a meta-analysis.

Depression

Of the seventeen studies that reported a depression outcome, eight studies( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 – Reference Nieman, Custer and Butterworth 19 , Reference Jenkinson, Doherty and Avery 25 ) found that the dietary intervention resulted in statistically significant improvements in depression scores when compared with a control group. The magnitude of effect, among the positive studies reporting the requisite data, ranged from 0·19 to 2·02 (Cohen’s d)( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 , Reference Garcia-Toro, Ibarra and Gili 15 – Reference Ghroubi, Elleuch and Chikh 17 , Reference Jenkinson, Doherty and Avery 25 ). The remaining nine studies reported no intervention effects. No study found the control group to produce superior outcomes. Table 1 provides detail of the depression scores for each study.

Anxiety/total mood disturbance

Of the ten studies that measured anxiety or total mood disturbance only two studies( Reference Ghroubi, Elleuch and Chikh 17 , Reference Andersen, Farrar and Golden-Kreutz 18 ) found that the intervention yielded significant improvements when compared with a comparator group. Conversely, eight studies found no significant between-group differences. No study found the control group to produce superior outcomes. Table 1 provides detail of the anxiety scores for the ten studies.

Depression outcomes categorised by composite interventions

When evidence was synthesised according to whether a study used a composite intervention (e.g. exercise, stress management) or focused solely on diet no clear differences in outcomes were detected (Table 1). We explored the relationship between weight loss, dietary intake and depression/anxiety outcomes. No obvious associations were found, thus this information is not presented.

Key characteristics of successful programmes

Table 3 provides a summary of the programme components (i.e. intervention delivery method, interventionist, dietary components, weight/exercise focus) for the seventeen studies that reported a depression outcome.

Table 3 A summary of the programme components of the seventeen studies that reported on a depression outcome

* Nieman 2000: reported on GWBS (General Well-Being Schedule) and POMS (Profile of Mood States) outcomes; results were only positive for GWBS scales in the exercise and diet group (ED).

Intervention delivery method

All studies (100 %) that achieved an improvement in depression score used only one mode of delivery to conduct their intervention, such as nutritional treatment meetings at home( Reference Endevelt, Lemberger and Bregman 16 ); a weekly class on weight-loss principles and nutrition guidelines( Reference Nieman, Custer and Butterworth 19 ); or written information only( Reference Garcia-Toro, Ibarra and Gili 15 ). The most common forum was face-to-face treatment in an individual or group setting( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 , Reference Merrill, Taylor and Aldana 14 , Reference Endevelt, Lemberger and Bregman 16 – Reference Nieman, Custer and Butterworth 19 , Reference Jenkinson, Doherty and Avery 25 ).

Of the studies that found no difference between intervention and control group, most (62·5 %) used multiple delivery modes such as CD-ROM programme and telephone call( Reference Glasgow, Nutting and Toobert 28 ); non-residential retreat and weekly meetings and/or computer-assisted program( Reference Toobert, Glasgow and Strycker 29 ); or a combination of group and individual sessions( Reference Wardle, Rogers and Judd 21 , Reference Hyyppa, Kronholm and Virtanen 22 , Reference Imayama, Alfano and Kong 24 ).

Interventionist

Approximately 85 % of studies that resulted in a positive outcome used a dietitian (or a professional trained in nutritional science) to conduct the intervention. Four of these studies( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 , Reference Endevelt, Lemberger and Bregman 16 , Reference Ghroubi, Elleuch and Chikh 17 , Reference Nieman, Custer and Butterworth 19 ) used a dietitian (or a professional trained in nutritional science) in isolation, whereas two studies included a dietitian with at least one other individual( Reference Merrill, Taylor and Aldana 14 , Reference Jenkinson, Doherty and Avery 25 ). Conversely, less than half (44 %) of the studies that produced null findings used a dietitian to facilitate the intervention. The remaining studies used a postdoctoral researcher, nutritionist (as opposed to a qualified dietitian) or a lay person.

Dietary components and weight/exercise focus

Among studies that achieved an improvement in depression score, 75 % of studies explicitly recommended a diet high in fibre and/or fruit and vegetables. The findings were similar (~78 %) for studies achieving no significant difference between intervention and control group.

With regard to fish intake, studies that produced null findings were more likely to have recommended an increase in fish consumption than studies achieving a positive outcome (66·7 % v. 12·5 %, respectively).

All studies (100 %) that resulted in non-significant between-group differences in depression outcomes recommended reducing red meat intake/selecting lean meat/following a low-cholesterol diet and/or included a weight-loss focus/reported on weight change. On the other hand, only 50 % of studies that resulted in significant improvements in depression scores made a specific reference to reducing red meat intake/selecting lean meat/following a low-cholesterol diet or had a weight-loss focus/reported on weight change.

Quality rating

A relatively high proportion of studies received a positive quality rating; twelve papers were considered to be of high methodological quality (received a positive (+) rating) and the remaining five studies were considered to be of moderate methodological quality (received a neutral (ϕ) rating). No studies received a negative (−) rating.

Common features of studies that were assessed as lower quality related to the selection of study subjects, methods of handling withdrawals, failure to employ intention-to-treat analyses (some excluded randomised participants from analyses due to non-compliance), insufficient detail/absence of blinding and randomisation techniques, and potential contamination of the comparator group. The online supplementary material 2, Supplemental Table 2 provides details of the quality assessment scores for included studies.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

The aim of the present review was to synthesise findings from existing RCT in order to evaluate the impact of dietary interventions (with a whole-of-diet approach) on depression and anxiety outcomes. Indeed, there is evidence from controlled trials that dietary interventions can result in improved depression scores among different clinical and healthy populations. Successful interventions yielded an effect size for depression scores between 0·19 and 2·02, which is a small to very large effect and is comparable to pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy( Reference Pinquart, Duberstein and Lyness 30 ). However, the evidence was not consistent, with just over half of studies revealing no effect on mental health outcomes and a lack of evidence of treatment effects for anxiety.

We found that the interventions shown to produce positive effects shared similar characteristics including: a single delivery mode; a qualified dietitian to deliver the intervention; and being less likely to recommend reducing red meat intake/selecting lean meat/following a low-cholesterol diet.

The importance of these features is supported by previous evidence. For example, nutrition education and counselling facilitated by a registered dietitian within a cardiac rehabilitation programme has been associated with improved diet-related outcomes when compared with patients receiving general education from cardiac rehabilitation staff( Reference Holmes, Sanderson and Maisiak 31 ). While low-cholesterol diets or those encouraging a reduction in red meat intake are frequently designed for reducing chronic disease risk, such a diet may not be the best strategy for achieving improvements in mental health. Inadequate intake of red meat has been linked to a greater likelihood of depression or anxiety in women, when compared with those consuming the recommended amount( Reference Jacka, Pasco and Williams 32 ). Moreover, low cholesterol may have a detrimental impact on mental health( Reference Engelberg 33 ).

Strengths and limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, the present systematic review is the first of its kind. A strength of the review is that it included only RCT – the highest level of evidence( 34 ). The search strategy applied was comprehensive, and methods of study selection and inclusion criteria were determined a priori. Moreover, all studies used validated measures of depression and anxiety. However, it should be noted that there were a multitude of different mental health assessment tools utilised in the included studies, making direct comparisons difficult. Further, only four authors specifically stated that their study was powered to detect a statistically significant difference in depression and/or anxiety scores. Importantly, the heterogeneous nature of the dietary interventions precluded direct comparisons and meta-analyses.

Of the ten studies that reported on dietary adherence or change in dietary intake, all studies used validated tools to measure dietary intake. The majority of these studies( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 , Reference Nieman, Custer and Butterworth 19 – Reference Wardle, Rogers and Judd 21 , Reference McMillan, Owen and Kras 23 , Reference Jenkinson, Doherty and Avery 25 , Reference Toobert, Glasgow and Strycker 29 ) included 3 d to 7 d food diaries. In practice, diet history interview and 7 d food diaries interchangeably serve as the ‘gold standard’ dietary assessment tools( Reference Hoidrup, Andreasen and Osler 35 ). However, it is readily acknowledged that all methods that rely on self-reported dietary intake are subject to measurement and systematic error( Reference Trabulsi and Schoeller 36 ). Biochemical data from serum or blood samples provide a more objective measure of nutritional status and dietary intake( Reference Bach-Faig, Geleva and Carrasco 37 ), yet are not commonly reported due to the associated expense and labour intensity; only two studies( Reference Forster, Powers and Foulds 20 , Reference Einvik, Ekeberg and Lavik 38 ) reported participants’ fatty acid levels or plasma micronutrient status.

While our findings are equivocal, substantial methodological limitations of the reviewed studies made it difficult to adequately answer the research question. In particular, the fact that only one study specifically included people with a depressive or anxiety illness( Reference Garcia-Toro, Ibarra and Gili 15 ), while other studies specifically excluded those with pre-existing mental health symptoms or disorders( Reference Endevelt, Lemberger and Bregman 16 – Reference Nieman, Custer and Butterworth 19 ), made it far less likely that effects on mental health parameters by dietary interventions would be detected. The majority of studies included individuals with lifestyle diseases (e.g. cancer, T2DM, overweight/obesity or hypercholesterolaemia), some examined only one gender( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 , Reference Andersen, Farrar and Golden-Kreutz 18 , Reference Nieman, Custer and Butterworth 19 , Reference Hyyppa, Kronholm and Virtanen 22 – Reference Imayama, Alfano and Kong 24 , Reference Toobert, Glasgow and Strycker 29 , Reference Einvik, Ekeberg and Lavik 38 ) and a number of study samples consisted of primarily white adults with a high education level( Reference Scheier, Helgeson and Schulz 13 , Reference Merrill, Taylor and Aldana 14 , Reference Andersen, Farrar and Golden-Kreutz 18 , Reference Imayama, Alfano and Kong 24 , Reference Kiernan, King and Stefanick 26 ). Hence, the findings may not be generalisable to other clinical and general populations. There was also substantial variation with regard to participants’ total exposure to the intervention; dietary intervention sessions offered ranged from one to sixty-two sessions and length of follow-up ranged from 10 d to 36 months. These limitations should be borne in mind when evaluating the significance of the results.

Only research articles that evaluated diet as a whole were included in the present review. This is of great relevance as not only do analyses of single nutrients ignore important interactions between components of a diet( Reference Sofi, Cesari and Abbate 39 ), but individuals do not naturally consume foods or nutrients in isolation. As a result, there is heterogeneity across many of the dietary interventions included herein. The review has attempted to address this issue by carefully examining each dietary intervention and allocating each component, such as increasing vegetable intake or reducing red meat intake, to a predetermined category to allow direct comparisons to be made between studies. The dietary information collected was based on the descriptions provided in each publication. Studies were excluded from the review if they failed to highlight the main dietary components of the intervention; therefore it is possible that some studies that were potentially relevant to review were excluded due to poor reporting/inadequate detail of the intervention.

Many studies failed to provide detailed information regarding techniques that interventionists employed to assist with achieving dietary compliance (e.g. counselling, motivational interviewing). Thus, ascertaining which intervention aspects (delivery techniques, group of foods or single nutrients) led to improved outcomes was difficult, which may hamper replication of these interventions. Finally, the inclusion of composite interventions (e.g. diet and physical activity or diet and n-3 PUFA supplementation) may have hindered our ability to elucidate the direct impact of dietary improvement on mental health outcomes.

Implications

Notwithstanding the methodological limitations of the present review, there is evidence that interventions with a whole-of-diet approach can achieve improvements in depression outcomes. This is an important finding as it suggests that dietary interventions could potentially be used as a treatment and preventive approach at the clinical and population level. The potential for dietary intervention to be employed as a prevention strategy may be of benefit when considering evidence from epidemiological studies that have shown a healthy dietary pattern may be protective against depression( Reference Sanhueza, Ryan and Foxcroft 4 – Reference Akbaraly, Brunner and Ferrie 6 ). These benefits are in addition to the already established evidence indicating that greater adherence to a healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, can significantly decrease the risk of overall mortality, mortality from CVD, incidence of or mortality from cancer, and incidence of Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease( Reference Sofi, Cesari and Abbate 39 ). Additionally, depression appears to share common pathophysiological mechanisms with metabolic syndrome, obesity and CVD( Reference Sanchez-Villegas and Martinez-Gonzalez 5 ) and several major cardiovascular risk factors are more prevalent among depressed individuals( Reference Sanchez-Villegas and Martinez-Gonzalez 5 ). Thus, evidence to date from epidemiological studies and RCT indicates that incorporating lifestyle recommendations, such as dietary improvement, into clinical practice and public health messages may contribute to a reduction in depressive symptoms, as well as providing additional benefits for the prevention and management of highly prevalent chronic disease states such as CVD, obesity and T2DM. This approach has the potential to reduce the public health burden of common mental illness as well as chronic diseases.

Conclusions

The present review of RCT has demonstrated that dietary intervention studies have the potential to achieve improved depression scores. The paper provides some insight into the key components that are likely to achieve improved depression outcomes. Appropriately powered RCT evaluating the impact of dietary improvement on mental health outcomes in those with clinical disorders are required( Reference O’Neil, Berk and Itsiopoulos 40 ).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Sarah Dash (S.D.) for replicating the systematic search of the literature. Financial support: R.S.O. is currently supported by a PhD scholarship from La Trobe University and Deakin University. A.O. is a recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Postdoctoral Training Fellowship (#1052865). F.N.J. has received Grant/Research support from the Brain and Behaviour Research Institute, the NHMRC; Australian Rotary Health; the Geelong Medical Research Foundation; the Ian Potter Foundation; Eli Lilly; and The University of Melbourne. F.N.J. has been a paid speaker for Sanofi-Synthelabo; Janssen Cilag; Servier; Pfizer; Health Ed; Network Nutrition; Angelini Farmaceutica; and Eli Lilly. F.N.J., C.I. and A.O. have received funding from Meat and Livestock Australia. These funding sources had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: R.S.O. contributed to the conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; as well as preparation of the manuscript for publication. A.O., C.I. and F.N.J. contributed to the design of the work; analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation of the manuscript for publication. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014002614