Introduction

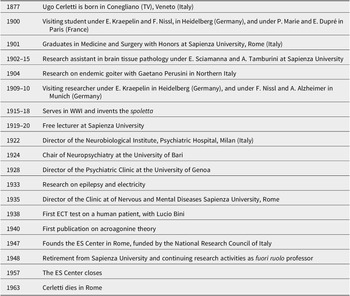

While the history of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been widely explored internationally, acroagonine theory, formulated and tested by the father of ECT, Ugo Cerletti, in the 1940s–50s, has received scarce attention in scholarly work on the history of biological psychiatry and neurosciences. Acroagonine is the name Cerletti gave to liquid substances he conjectured to be produced by the brain under electroconvulsive treatment. Cerletti held these substances responsible for depressive patients’ recovery after ECT, and thus, he tried to extract them from electro-shocked animals’ brains to use as an injectable drug for psychiatric patients (Figure 1). With the exception of a few publications by Italian scholars,Footnote 1 acroagonines have been rarely mentioned in international works. Given ‘we know almost nothing about the neurological mechanisms of ECT’, acroagonines have been referred to by experts as ‘a pharmacological replacement for ECT… [that] did not work out’.Footnote 2 Acroagonine research has thus been considered unsuccessful, irrelevant, and non-influential, driven by the goal of pharmacologically emulating the mechanisms of ECT.

Figure 1 Acroagonine vial.

Not only does common historiography on psychopharmacology neglect acroagonine research, it also pays little heed to ECT’s role in the birth of psychotropic drugs.Footnote 3 Even if ECT is currently subject to a historiographic revaluation, the popular view still held is that psychopharmacology overcame the need for ECTFootnote 4; indeed, it is generally believed that ECT and pharmacological treatments should be understood as two contrasting therapeutic approaches.Footnote 5 There have been, however, a few local exceptions to this viewpoint. Certain Italian scholars, for instance, have suggested that Cerletti opened ‘the doors of the psychopharmacological turn in psychiatry’.Footnote 6 Others have gone further by saying that acroagonines were ‘precursors to the psychopharmacology that would develop further after World War II’.Footnote 7 This is an interesting interpretation of the history of how psychopharmacological treatment has developed, which remains as yet unexplored.

There is another aspect of the acroagonine hypothesis that, even though cited by prominent historical sources, has not been fully investigated.Footnote 8 That is, acroagonine theory originated from the insight that mental disorders and treatments – particularly depression and ECT – must be understood in neuroendocrine terms. Accordingly, the neuroendocrine explanation of ECT, as well as neuroendocrine psychiatry, in general, were consistently defended from the late 1970s.Footnote 9

As will be argued in this article, acroagonine theory has relevance for both the origins of psychopharmacology and the emergence of the neuroendocrine explanation of mental illness. Specifically, Cerletti emphasised the role of a precise brain structure, the diencephalon, in the action of ECT, and more specifically, he associated mood disorders with hormonal-hypothalamic dysfunction. Diencephalon localization received careful consideration in late-1950s psychiatry after it turned out to be a crucial intuition that led Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker to test chlorpromazine, an antihistaminic with limbic neural activity, on psychiatric patients. According to Francophone historiography,Footnote 10 Jean Delay was not only the initiator of contemporary psychopharmacology but also the originator of the diencephalon hypothesis, while Cerletti came after and acknowledged Delay’s influence. This article attempts to refine such historical narrative, arguing that acroagonines, a neglected theoretical and research stage of twentieth-century biological psychiatry, though later proven false, paved the way for subsequent scientific insights and developments in contemporary psychiatry.

Along with other known archival and bibliographic sources, this article makes use of unexplored archival materials, herein named the ‘ES Section’ after the pen-marked abbreviations present on each of the binders, stored at Sapienza University of Rome. The ES Section is part of the Ugo Cerletti Archival Collection located at the Library of Human Neurosciences at Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, found in the New Historical Archive of the Child Neuropsychiatry Section. The ES Section consists of ten non-inventoried, unnumbered and unordered binders originally pen-marked ‘ES’, which were here given provisional and casual numbers under a preliminary inventory (herein ‘Unit’). The records (miscellaneous print items, correspondence, notes, photos, drawings and other materials) are largely in Italian, are mostly dated between 1946–1958, and have been thus attributed, during this research project, to Ugo Cerletti’s activities at the ‘Center for the study of the physiopathology of electro-shock’ at the National Council of Research of Italy, described hereafter. As far as is currently known, the ES Section is presumed to be the only collection of Ugo Cerletti’s records on ECT research that remains in Rome, after two shipments of Cerletti’s papers were sent to the USA by family following his death, in 1965 and 1972.Footnote 11 This Ugo Cerletti Collection, consisting of twenty-one boxes of archival records and six other folders of honours, is now held under the Menninger Historical Psychiatry Collections at the Kansas State Historical Society (KSHS) Archives in Topeka (Kansas, USA), having previously been stored at the Menninger Foundation Archives. The KSHS Archives also store the related Lucio Bini Collection, consisting of two folders, one of which has been digitised and shared online. The KSHS Cerletti and Bini collections have been used as source material in producing this article.

A third Ugo Cerletti Archive, located at the Italian Historical Museum of War in Rovereto (TN) (Italy), is dedicated exclusively to a Cerletti’s military invention he made while serving in the army in WWI, the delayed-action fuse, or spoletta. Since the Rovereto collection contains no records on his neuropsychiatric research, it has been excluded from this research.

This article used the author’s translations of the original Italian archives. As an Italian native speaker, the author was aware of the interpretative difficulties of the task and hopes she succeeded in replicating Cerletti’s tone and intention in English.

The plight of a passionate mind

Following the very recent vote of the Superior Council of P.E. [Public Education], which granted no exception – admitted by the Law – to the retirement of Professors who have reached the age limits from their Institutes, I will have to leave the Clinic I lead at the end of next October.Footnote 12

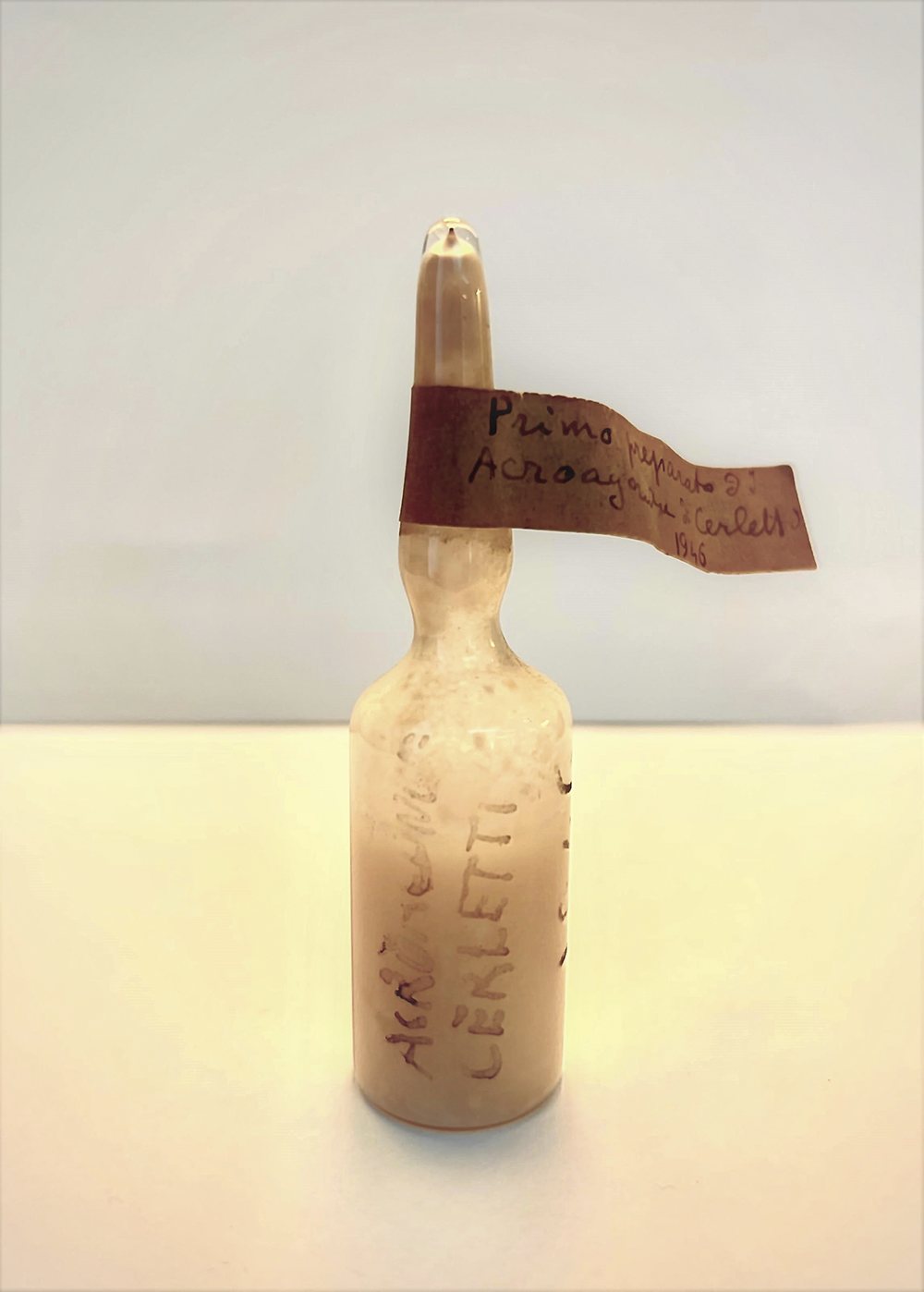

With this pencil-drafted note to the then President of the National Research Council of Italy (CNR),Footnote 13 Ugo Cerletti (1877–1963) (Table 1), the father of the celebrated ECT, that he and Lucio Bini introduced in 1938,Footnote 14 was expressing his deep sense of frustration. From his reference in the letter to ‘the next October’, and to research conducted in 1947–8, we may infer Cerletti wrote this around 1948. At the age of retirement, Cerletti started a turbulent and costlyFootnote 15 legal battle that came to a negative end. Supported by his lawyer Mario Bracci, legal professor and dean of the University of Siena,Footnote 16 Cerletti strenuously fought against the then Minister of Public Education Guido Gonella, a prominent Christian Democratic deputy, who refused to extend Cerletti’s position as director of the Clinic of Nervous and Mental Diseases at Sapienza University in Rome.Footnote 17

Table 1. Key events in Ugo Cerletti’s biography.

Cerletti’s experience was not isolated. In the post-war era, many academics were opposed to a law enacted during the fascist period, the so-called De Vecchi Law (1935). Previously, a restriction on the maximum working age that prevented professors from working beyond 70 years old was used to exclude dissidents of the fascist regime from Italian academia. However, the Constituent Assembly of Italy, established to draft the post-war Constitution in 1946, considered the norm unjust and re-fixed the limit to 75 years old for professors, like the previous Rava Law (1909).Footnote 18 The lower limitation was maintained for directors of institutes or university chairpersons, who could continue to serve in office only if of ‘exceptional merit’. The press reported that, incredibly, of the sixty-two applications submitted by different faculties that year – among which was Cerletti’s – all were rejected because the merit criteria they had to meet were too restrictive and ‘naïve’.Footnote 19 Besides, the number of members required to pass the quorum (two-thirds of the Superior Council of Italy) was rarely present at the meetings. A witness reported that, of the scholars put forward, Cerletti got the most favourable votes.Footnote 20 ‘After all, my electroshock has conquered half the world’,Footnote 21 he remarked to Agostino Gemelli, while thanking him for his support of the application to continue working as a professor.

From his notes, it appears Cerletti viewed the enforced retirement as ‘disturbing’.Footnote 22 Cerletti felt persecuted, alienated, and doomed to join the ‘“dead” in science’.Footnote 23 The dismissal of his application had been a greatly humiliating experience, especially considering how he described his obsession for science and research from a very young age as ‘a true addiction’.Footnote 24 Besides this, as with many others, Cerletti had encountered and overcome tremendous difficulties in seeking to pursue his research during the war, including loss of assistants and lack of material resources.

‘This happens at the moment when my research on “Acroagonines” was most active’ – Cerletti complained to the CNR President in the above mentioned letter – ‘[and when acroagonines] have given increasingly encouraging results in various fields, especially in various mental illnesses and nervous diseases such as acute poliomyelitis and other forms of encephalitis, in addition to that provoked by rabies’. Cerletti had invested his hopes, energies and personal moneyFootnote 25 in this new audacious project conceived as an extension of his ECT research. With support from an academically powerful and charismatic professor of general pathology at Sapienza and leading figure at the National Research Council, Guido Vernoni (1881–1956),Footnote 26 and help from his long-standing friend and director of the Provincial Asylum Santa Maria della Pietà, Francesco Bonfiglio (1883–1966),Footnote 27 Cerletti founded a ‘Center for the study of the physiopathology of Electro-shock’ (ES Center). The CNR Presidency Council had approved the foundation of the ES Center at the Sapienza Clinic on 28 January 1947, allocating a yearly fund of 1 000 000 LireFootnote 28 (around 20 000 euros as today). These funds were, for Cerletti, ‘an oasis in the middle of the desert of 50 years of hardship’.Footnote 29 This center and others, following a model of previous CNR centres established in 1929,Footnote 30 were intended to promote the rebirth of Italian scientific research after the Second World War.Footnote 31 In March,Footnote 32 CNR approved the proposal made by Vernoni and Cerletti to move the experimental activities of the ES Center from the Clinic, where Cerletti had been confined and left without patients, to the Provincial Asylum in Rome, led by his friend Francesco Bonfiglio.

The acroagonine theory

The ES Center was aimed at studying extracted liquid substances from electro-shocked animals’ brains (especially, from pigs and sheepFootnote 33) that Cerletti named acroagonine (referred to as ‘acroagonines’ or sometimes ‘acroagonins’ in English), or substances of high biological activity, ‘from the Greek ἄκρος (utmost) ἀγών (struggle)’.Footnote 34 Cerletti explored various terms from Ancient Greek (istagonina, telagonina, cerlagonina, etc.) before finding one that was suitable.Footnote 35 Mindful of the experience with the ECT apparatus prototype in 1939, which he accepted to be patented by Lucio Bini only – an event that later caused tensions between the two,Footnote 36 – Cerletti immediately patented the name in Italy in 1948,Footnote 37 and then in 1953, he applied to the German,Footnote 38 USA,Footnote 39 and UKFootnote 40 patent offices. Initially, he used the term ‘agonine’ as a generic label, believing these substances would possibly be found in other organs beyond the brain (‘neuro-agonine, cardio-agonine, angio-agonine, pneumo-agonine, epato-agonine, etc.’ Footnote 41). Cerletti’s hypothesis was that injections of these brain fluids in mental patients would produce the same – if not better – clinical effects of electroshock applications. The ‘success’ of ECT, for him, ‘could not be considered an end point, but indeed turned out to be the starting point of a series of difficult questions that arose due to their practical importance and their theoretical developments’.Footnote 42 He needed to understand how electricity affected ‘certain autonomic nervous centres with characteristic symptoms and with humoral and hormonal shifts’, mediated by alleged curative epileptic-like convulsions.Footnote 43 He also ‘thought to compare these particular modes of reactions in a large series of animals from very different species’,Footnote 44 a type of research that he and Lucio Bini had already explored since 1937.Footnote 45 They had so found that such ‘electric current… does not produce irreparable organic alterations in the brain’ – this is why Cerletti was supposing the presence of ‘diffusive… modifications’.Footnote 46

Cerletti formulated as soon as 1940 his own hypothesis about the specific neurophysiological reactions to electroshock applications in a long monographic article entitled L’Elettroshock. Footnote 47 Cerletti believed that electroshock efficacy was due to stimulating some homeostatic processes in the brain, specifically in the meso-diencephalic area. His ideas came from Walter Cannon’s concept of homeostasis and other neuro-ethological research (e.g. Mikhail Kroll, Philip Bard and Curt Richter).

The idea of localising the epileptogenic region in the diencephalic area had been suggested before, in 1932, by Albert Salmon.Footnote 48 His assistant Giovanni Bollea and the physicist Angelo Manfredi showed, through studies on human corpses and dead and alive dogs, that the distribution of the electric current could affect subcortical structures.Footnote 49 For the occasion, Bollea and Manfredi built a two-electrode device detecting the potential difference in 1-cm extremes of the brains. They showed ‘that the electrical stimulus does not cross the brain from electrode to electrode, but that, having reached the stratum of the cerebrospinal fluid in which the brain is immersed, it follows this path… it passes especially into the large basal cisterns of the brain, it reaches the fourth ventricle, and through the aqueduct of Sylvius [it reaches] the third ventricle, where it acts on the surrounding vegetative centres’.Footnote 50 Cerletti’s localization in the diencephalon was generic, although in 1951, he looked favourably on Alois Kornmüller’s hypothesis on glia cells, which Cerletti had investigated with Franz Nissl in Heidelberg when, as a student, he was training in histopathology.Footnote 51 Plus, research on glia cells supported Ladislas Meduna’s hypothesis of the antagonism of schizophrenia/epilepsy, which inspired shock therapies, ECT included.Footnote 52

Yet, diencephalic localization contrasted with another popular idea, that is, that ECT stimulated the brain only cortically.Footnote 53 Cerletti’s assertion that ‘what is obtained electrically from the cortex can only be an echo’ was proven by studies with EEG in electroshock applications.Footnote 54 According to Cerletti, not only loss of consciousness (e.g. shock, sleep, apnea, and coma), but the onset of consciousness itself had to be localised within the meso-diencephalic brain area, and not – like many other authors suggested – in the frontal cortex.Footnote 55

Taking inspiration from Charles Darwin’s remarks on emotions (especially the idea of a syndrome terror-defence),Footnote 56 Cerletti supposed that in a phase subsequent to the shock (the ‘agony’ phase), which he called ‘counter-shock’ or transition phase, the brain was secreting hormonal substances conducting a state of so-called general adaptation syndrome (GAS). Owing much to Cannon’s physiology,Footnote 57 Hans Selye identified this pattern of responses under stress (i.e. alarm, resistance, and exhaustion).Footnote 58 Cerletti interpreted this state as a ‘defence reaction against future exposure to the same stress’.Footnote 59 Other coeval references were Constantin von Monakow and Raoul Mourgue on terror neurosis, or Kurt Goldstein’s ‘catastrophic reaction’.Footnote 60

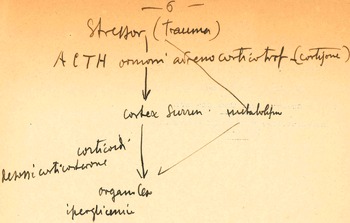

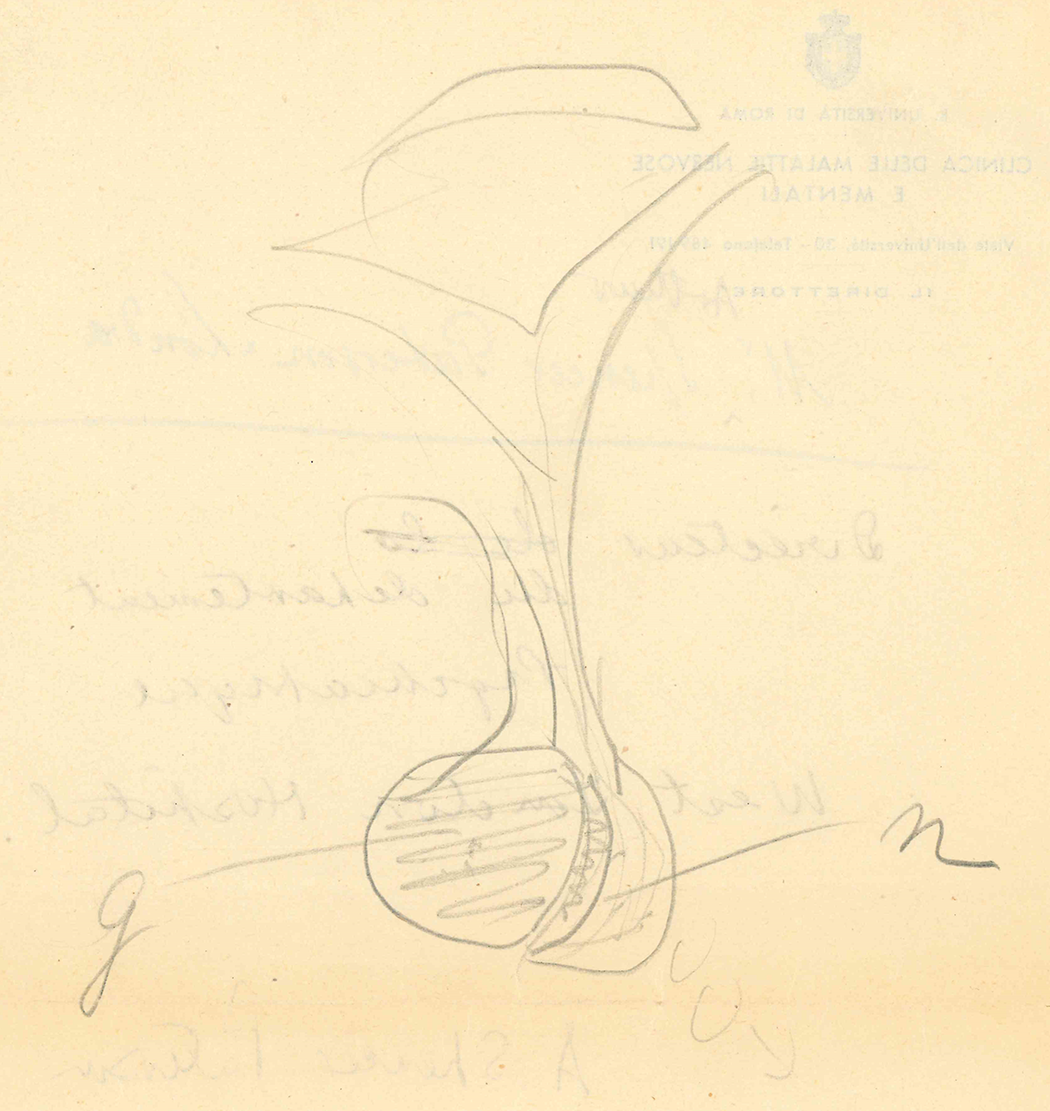

Cerletti thought of a homeostatic balance in what would be later called the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. This emerges from his drawings where a trauma or stressor stimulates the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and so cortisol production, then the adrenal gland is involved, and finally deoxycorticosterone and hyperglycemia are originated (Figure 2).Footnote 61 He stored another sketch of a pituitary gland (Figure 3).Footnote 62

Figure 2 Action of the adrenocorticotropic hormone.

Figure 3 Pituitary gland.

Finally, in Cerletti’s imaginative mind, acroagonines were sort of ‘vitalizing substances’, secreted by the brain for hormonal balance, which permitted ‘specific resistance’ to less or more severe pathologies,Footnote 63 from hair loss,Footnote 64 to psoriasis,Footnote 65 and terminal conditions,Footnote 66 beyond mental diseases. An analogous theory was that of ‘biostimulines’ postulated by the Russian Vladimir Petrovich Filatov for tissue grafts, a theory that Cerletti mentioned in different occasions,Footnote 67 or that of the conditioning of immune response by Serguei Metalnikov. In 1945, the effects of electricity on the diencephalon had been linked to the production of antibodies and antitoxins by injecting electro-shocked patients’ plasma and serum into other patients.Footnote 68 Other authors like Diego De Caro and Luigi Aru from Cagliari criticised Cerletti’s vitalistic interpretation, but shared this immunological-like hypothesis by focusing more on alleged bacteriological processes in mental illness and recovery.Footnote 69 Following research of the late 1800 and 1920s on infective properties of mental patients’ blood and liquor,Footnote 70 they decided to test the emulsions in the laboratory by using bacterial cultures. In 1948, following research on rabbits conducted by Cerletti’s assistant Mario Felici at the Roman Clinic, Ottavio Vergani and G. Garavaglia tested the link between ECT and specific antibodies (i.e. typhoid agglutinins) in Milan by vaccinating forty individuals against typhus and then electroshocking half of them; their conclusions from this work, however, were ambiguous.Footnote 71 In the years 1949–50, also Alfredo Poloni (Istituto Antirabbico Italiano) conducted research on liquor of electro-shocked subjects, another series of articles Cerletti stored.Footnote 72

For conceiving the acroagonine hypothesis, Cerletti and the others were actually overestimating some poor evidence coming from his team’s experiments, which were showing partial recovery or delayed pathological manifestations in some acroagonine-inoculated rabbits and monkeys infected from fixed and aggressive viruses like rabies or polio.Footnote 73

Cerletti’s team wished not only to find these effects,Footnote 74 but also to reproduce them. Whereas with ECT one needed to ‘repeat the applications over and over again’,Footnote 75 Cerletti now wished to find some quicker, safer, and less terrifying means than electricity, or – as he used to say – an ‘electroshock by proxy’.Footnote 76

Experimenting on acroagonines

Experiments on acroagonines had started officially on 14 March 1947.Footnote 77 A well-trained staff at the Roman slaughterhouse was daily electroshocking the hogs, and then carefully killing them so to extract their brains without any other modifications. The hogs’ brains were brought to the Sapienza University Hygiene Institute, where sterile emulsions were prepared. A team headed by Vittorio Puntoni, dean of the medical faculty and chair of hygiene at Sapienza, pulped the brains in mortar. They diluted them in aqueous suspension (10%) and 1% solution of phenol, a method already employed for rabies vaccines to avoid ‘the delicate question of the toxicity of heterogeneous brain extracts’.Footnote 78 In 1950, French researchers (P. Gley, J. Rondepierre, and J. Oulès) used another method, that of insulin extraction.Footnote 79

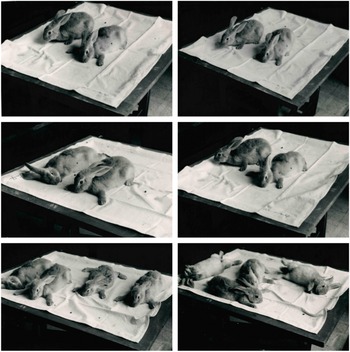

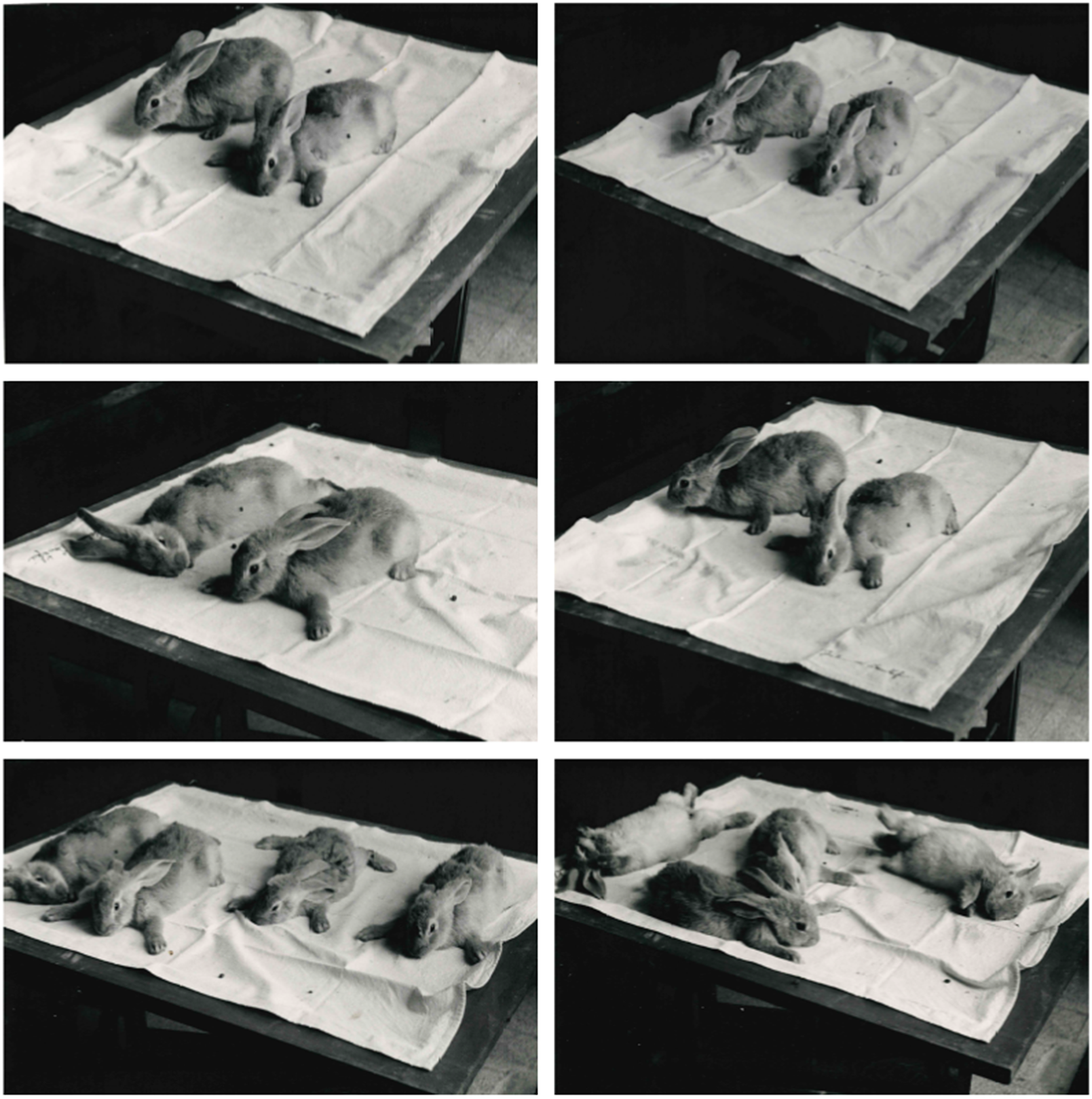

Before treating humans, Cerletti’s team tested rabbits (Figure 4),Footnote 80 in order to see whether rabies-infected rabbits might have shown any effects from acroagonine inoculations, and then they injected a group of polio-infected monkeys donated by the Superior Health Institute.Footnote 81

Figure 4 Experimental rabbits.

Afterwards, in a 1947 speech at the Superior Health Institute, Cerletti announced to have performed intramuscular injections on human subjects of these emulsions on thirty-six dysthymic inmates at the Sapienza Clinic and at the Roman asylum, and that he had injected himself as well.Footnote 82 Even if not properly randomised controlled trials, which would have made them among the first in the neurosciences, it is worth noting that twelve patients received initially (for about 3 days) emulsions from hogs’ non-shocked brains (control group) and were then compared to patients treated only with emulsions from hogs’ shocked brains (experimental group).Footnote 83 In some particularly resistant cases, ECT was administered some days after the shocked-brain-emulsions. It is unclear how the patients were assigned to one group or the other. However, Cerletti claimed to have obtained significant reactions in the experimental group, compared to the control group.Footnote 84 Cerletti’s team stored graphs reporting observations on four patientsFootnote 85 (a 81-year-old woman and three men), only one presumably belonging to the list of thirty-six, and a prescription on another,Footnote 86 that they treated with 2 cc, 5 cc, 10 cc emulsions. Notes on other six injected patients (three men and three women, aged from 19 to 35 years old, diagnosed depression or schizophrenia) were also stored.Footnote 87

What Cerletti wished to get with his request to the CNR President in 1948 was financial aid for carrying out this research. Cerletti had noted that he wanted to obtain ‘200 vials of 5 cc’ of these liquid substances (Figure 1) from each of 80 hogs he planned to request, and that his goal was to get ’10 000 vials for clinical trials’.Footnote 88 He planned to use these vials for ‘ten treatments in ten institutes’.Footnote 89 An Italian pharmaceutical company, in partnership with Rhône-Poulenc, rejected Cerletti’s requests to produce the vials due to the difficulties in doing so and for other bureaucratic reasons.Footnote 90 A year later, Cerletti sought to enlist a European company – maybe a Dutch, but not an Italian or a German company – for the production.Footnote 91

He also needed to hire some assistants now that, due to his forced retirement, he had been left without the ability to pay his collaborators from the Clinic funds. ‘Cerletti and his collaborators, including in the first place Longhi and Fiume, as well as a host of doctors from the Clinic and the Psych. Hosp’. were ‘working feverishly to dose the active power of the acroag. [acroagonines] in units as to be able to use them in ample tests in the various nervous and ment. [mental] diseases in the near future’.Footnote 92

The faithful collaborators who joined the enterprise were Lamberto Longhi (1909–97), Sebastiano Gaetano Fiume (1913–2000), Giovanni Martinotti (1905–78), whose contracts were calculated to cost respectively 80 000, 50 000 and 46 370 Lire.Footnote 93 They ‘up to now’ had worked ‘without any compensation from the center’.Footnote 94 Also Giovanni Bollea (1913–2011) and Bonfiglio’s son Giovanni were involved, as well as others.Footnote 95 Although at the time Cerletti was at loggerheads with his assistant Lucio Bini – the designer of the ECT apparatus prototype they co-invented – and with Lothar Kalinowsky,Footnote 96 his relationship with Lamberto Longhi was solid throughout his career.Footnote 97 Cerletti brought Lamberto Longhi with him from the University of Genoa to the Sapienza Clinic in Rome in 1936.Footnote 98 In Genoa, Longhi assisted Cerletti on studies about the endemic goiter,Footnote 99 whereas in Rome he was initially assigned to research on the effects of cardiazol/metrazol,Footnote 100 and then he joined electroshock studies. Twelve years later, in August 1948, instructed by Guido Vernoni, Cerletti delegated Longhi – ‘very diligent, insightful workmate and generous person’Footnote 101 – to withdraw a sum of money sent by the CNR (500 000 Lire) for the use of the ES Center.Footnote 102 Longhi’s presence in the activities of the center was definitely strong.Footnote 103

As for the others, Sebastiano Fiume, a ‘voluntary assistant’ for Cerletti since 1939, had been confirmed with a paid position in Cerletti’s team from November 1943, in order to replace Ferdinando Accornero, another Cerletti’s assistant who was in the Army.Footnote 104 He continued to work there after Accornero’s return in 1947, when Accornero joined the research and performed the first acroagonine inoculations on rabies-infected rabbits.Footnote 105 Giovanni Martinotti, who had been working unpaid at the Clinic since 1938, got a post starting in 1946, and then was assigned to Vernoni’s lab to train in the ‘histopathological technique of the nervous system’.Footnote 106 Finally, Giovanni Bollea, who graduated in Turin and worked as a ‘voluntary assistant’ in Rome from 1939 on, had been appointed ‘assistant in charge’ in 1944.Footnote 107 A couple of years later, Cerletti – who with Sante De Sanctis contributed to the birth of child neuropsychiatry in ItalyFootnote 108 – encouraged Bollea to train in children’s mental affections in Lausanne. Bollea was initially fully involved in the activities of the ES Center by providing relevant publications.Footnote 109 However, it was during his long stays in Paris, in 1948–9, that Bollea established strong links with Georges Heuyer, an international figure and Cerletti’s friend,Footnote 110 and at this time he was captivated by child neuropsychiatry.

Discouraging results and the end of the acroagonine season

The expectations of the ES Center’s research were high. Already at the end of 1947, we have a record of the psychiatrist Umberto De Giacomo offering Cerletti to test this new treatment at the psychiatric hospital in Lecce.Footnote 111 During the same days Antonio D’Ormea, director of the Psychiatric Hospital in Siena, reported to have tested twenty vials on an anxious-depressive woman and given other twenty vials to a colleague.Footnote 112 In 1948, the vials had reached different psychiatric centres throughout the Italian peninsula, including Turin, Milan, Brescia, Venice, Bologna, Siena, Perugia, and Brindisi.Footnote 113 In early July 1948, the psychiatrist Ferdinando Ugolotti, Director of the mental asylum in Pesaro, was regretfully informing Cerletti ‘they achieved nothing’ from injections with acroagonines on a manic-depressive patient, in contrast to successful results obtained with 3–4 ECT applications on the same patient.Footnote 114 In late September of the same year, Ettore Menichetti, at the Psychiatric Hospital in Perugia, achieved positive results in tests on three patients, but wished to take time to produce a proper report.Footnote 115 Only a few months before, in January 1948, a summary published in The Lancet might have put pressure on this research.Footnote 116 Arthur Spencer Paterson, who worked at the West London Hospital and was anxious to visit Cerletti in March,Footnote 117 organised the publication. This prestigious announcement of Cerletti practicing inoculations on humans – ‘in doing so he has opened new vistas of speculation’ – might also have stimulated the attention acroagonines received internationally (this is confirmed by the many letters Cerletti got on this matter from foreign colleagues in the years 1949–53Footnote 118).

On 26–27 September 1950, the first Congrès mondial de psychiatrie in Paris, a cutting-edge venue organised by Jean Delay and Henri Ey at Sorbonne University, took place. The congress, the first after the war, gave birth to the World Psychiatry Association. In the fourth session chaired by the Brazilian psychiatrist Antonio Carlos Pacheco y Silva, Cerletti gave the first of three keynote speechesFootnote 119 and was then awarded an honorary degree by Sorbonne.Footnote 120 The following two speakers were the eminent shock therapists, Manfred Sakel and Ladislas Meduna. In another session, Cerletti presented also a black-and-white documentary edited with Longhi in collaboration with Istituto Nazionale Luce. The video, for which they were got a scientific prize in Rome,Footnote 121 showed the research on animals they conducted at the ES Center. The documentary, realized in two versions (1950, 1954), followed a tradition of scientific cinematography established at the beginning of the twentieth century in Italy and renovated after WWII thanks to investments from the CNR, the same research agency financing Cerletti’s experiments.Footnote 122 To produce it, Cerletti was given a sum of 800 000 Lire.Footnote 123 After a short theoretical introduction offered by Cerletti himself, the movie showed ECT administrations on nineteen vertebrates of different species in experimental settings (i.e. poikilotherms: carp, toad, frog, turtle, monitor lizard and boa; homeotherms: duck, swan, swan, penguin, rabbit, porcupine, cat, dog, pig, sheep, mutton and monkey) and described their motor and behavioural reactions. The video was driven by Darwinian insight, that is, looking experimentally for the evolutionary roots of the mechanisms of action of electricity on the animal brain. Its goal was clearly to show Darwin’s terror-defence theory. The documentary concluded that ‘convulsion is not a brute, chaotic discharge caused by electricity, but the expression in various forms of a particular constellation of phenomena preformed in the brain, with an alarm-defence character’.Footnote 124

A couple of months after the Paris Congress, Vincenzo Menichella at the Istituto dell’Assistenza all’Infanzia of the Province of Rome started treating twenty children (18–36 months), hospitalised in the luetic ward.Footnote 125 Ten were given shocked brain emulsions, ten were given non-shocked brain emulsions. It was reported that the emulsions protected all of them from an outbreak of paralytic polio in an adjacent ward. At a Congress in Taormina in 1951, Carmine d’Angelo reported to have injected eight elderly patients diagnosed with senile dementia at the Provincial Asylum in Rome.Footnote 126 Other forty-one patients, five of which affected by Parkinson’s disease, were treated there by an intern from Paris, J. M. Dell, in 1952.Footnote 127 Cerletti was overly optimistic in interpreting the results.

Curiously enough, in 1953, Cerletti got his last chance with acroagonines, when his friend Pacheco y Silva decided to invest in Cerletti’s acroagonines by involving a Brazilian company, Vincente Amato Sobriho s.a. in San Paolo. The admiration Pacheco y Silva had for Cerletti was profound, as he stated to the press.Footnote 128 The Hungarian psychiatrist Ladislas Meduna – inventor of the cardiazol shock therapy – who in the meantime had emigrated to Chicago and was close to Cerletti as well, tried to get some funding in the United States.Footnote 129 Phoenix physician Jacob Reichter and the Crease Clinic of Vancouver had invested in Cerletti’s brain serum.Footnote 130 These investments, however, came late as companies in Cuba, Buenos Aires and Rio had already started acroagonine production without Cerletti’s authorization.Footnote 131

Unfortunate events for Ugo Cerletti, however, came in 1956. Both the Brazilian and USA trials on acroagonines proved discouraging. On 20 February of the same year, Cerletti’s greatest supporter Guido Vernoni died.Footnote 132 In the absence of Vernoni, the ES Center could not survive. It was officially closed on 1 July 1957.Footnote 133 In the latter years, Cerletti had lost his academic influence, and precisely after 1952, when the newly appointed Clinic director Mario Gozzano had expelled Cerletti’s close collaborator Vittorio Challiol,Footnote 134 who was acting director in the years 1949–51 and favoured Cerletti’s activities at the Clinic. From that point, Mario Gozzano dismantled Cerletti’s team, including Bini, Martinotti, and finally Longhi, by making strong, false and humiliating accusations to them – they had little scientific production, he unfairly reported in different occasions to the Faculty.Footnote 135 They were actually very prolific by assisting Cerletti on his research on the effects of ECT, while Gozzano intended to build his own team dedicated to EEG. In 1949, Cerletti had pointed out that ‘during this last year alone, thirty-five works of my own team have been published or are in print’.Footnote 136 He had also somehow predicted the future of his team: ‘If a professor, who has publicly declared himself opposed to the E.S. [electro-shock] in a congress, comes to Rome’, he had said, alluding to Gozzano, then ‘all this fervour of activity will be radically cut off’.Footnote 137 Forced to resign from his assistant position in 1952, Giovanni Martinotti requested to stay without a stipend.Footnote 138 Lucio Bini, who had been offered a leading position at the San Camillo Hospital in Rome, left the Sapienza Clinic on 1 November 1956, but continued to deliver some courses.Footnote 139 Despite their tensions, in 1955, Cerletti went to great lengths to support Bini’s application to become director of the provincial asylum, the Santa Maria Della Pietà Hospital, a position he was never awarded.Footnote 140 Being fired just 11 days after the ES Center’s cessation (12 July 1957), Lamberto Longhi started a legal battle lasting 4 years, until he was reintegrated in 1961.Footnote 141 Cerletti unsuccessfully recommended Longhi for a psychiatry chair position at the Catholic University in Milan,Footnote 142 and for another within the Vatican Congregation.Footnote 143 While Martinotti continued teaching at the Santa Maria Della Pietà Hospital,Footnote 144 Fiume was deemed eligible to lecture at Sapienza.Footnote 145

Ferdinando Accornero, another intellectually active Cerletti’s collaborator, decided to continue his position as an assistant at Sapienza, from which he retired in 1975.Footnote 146 Interestingly enough, Giovanni Bollea – who since 1956 had been dedicated exclusively to child disorders at a ward at the Roman ClinicFootnote 147 – was the only one to find favour with Cerletti’s successor, Mario Gozzano, and was confirmed as a staff member at Sapienza, where a few years later he established a child neuropsychiatry institute.Footnote 148 Bollea was responsible for preserving Ugo Cerletti’s miscellaneous records, including the ‘ES Section’, at Sapienza University in Rome.Footnote 149

In March 1961, Gozzano defended himself by blaming Cerletti. He asserted that, in 1947, Cerletti should have located his CNR Center at the Clinic, instead of at the Provincial Hospital. ‘I certainly do not think that this was the best way to collaborate with me’,Footnote 150 Gozzano emphasised. Cerletti, however, had made this decision before Gozzano came to Rome. ‘And here we come to the question of your assistants, whom I would have dismissed one by one’, Gozzano continued. When he arrived in Rome, he stressed, he was told that Lucio Bini, like some others, had already applied for positions in other hospitals. He also mentioned that Bini thought Cerletti and Gozzano ‘had plotted behind his back’ to block his university career. As for Longhi, ‘he made no objection to my proposal not to reconfirm him’, Gozzano defended himself. ‘Thanks to my praise’, he even added, ‘Longhi’s appeal for a reintegration to Sapienza was accepted’. Gozzano also complained that Cerletti had convinced him to go to the Roman Clinic, where unfortunately, he had been welcomed by ‘a hostile environment’.

There were other advances regarding acroagonine research in the late 1950s – early 1960s, such as the investments by the Max Planck Institute in Germany, and a trip Cerletti made to the USA Electroshock Research Association in 1959. Moreover, traces of the acroagonine theory – especially the idea of a sleep/wake regulation, explored by Alvas Garcia already in 1950Footnote 151 – resisted in Cerletti’s latest publications.Footnote 152

Yet the season of acroagonines had ended by then. Cerletti had been left with a secluded office at the third floor of the Clinic and had gone back to exhausting research on endemic goiter with Lamberto Longhi,Footnote 153 his last scientific effort before passing away (25 July 1963).

Acroagonines in psychopharmacological and neuroendocrine research: the Cerletti–Delay competition

To explore the impact of acroagonines on subsequent research, we need to go back to the 1940s. In April 1949, Cerletti’s pupil Giovanni Bollea, who at the time was training in Paris at Georges Heuyer’s lab,Footnote 154 informed his mentor of the events at a faculty meeting at the University of Sorbonne when discussing possible nominations for honoris causa degrees:

Heuyer was close to Delay and says to him: I would propose Cerletti if I did not know that there were misunderstandings (or something like that) between you and him. Delay replies: You are right and you were right to remind me. … Then he stands up and proposes the name [Cerletti] himself.Footnote 155

Accordingly, Cerletti was awarded at the Congrés in Paris a year later, but it is worth clarifying the nature of the aforementioned disagreements. In June 1947, during the speech held at the Superior Health Institute in Rome on early acroagonine tests, Cerletti explicitly accused Jean Delay of plagiarism.Footnote 156 According to Cerletti, Delay publicly heralded the idea of the hypothalamic-diencephalic site of ECT action as his own, while Cerletti himself had formulated and analysed this idea, as part of his emerging acroagonine theory, in his first 1940 monography on the electroshock, published in a local journal in Italian (Rivista Sperimentale di Freniatria).Footnote 157 Cerletti blamed the Italian language and the fact that only years later, due to the circumstances of the war, did the Americans become acquainted with his work. Cerletti remarked that, ‘In 1946, we find it [the diencephalon hypothesis], largely paraphrased, in the II and III sections of Jean Delay’s volume L’Electrochoc and Psycho-physiologie without the name of its author [Cerletti] being mentioned once. And in many publications of subsequent years by other authors, for example, in the book by Delmas-Marselet, we see it cited as the diencephalic theory of Delay’.Footnote 158 These accusations were repeated in several of Cerletti’s handwritten notes.Footnote 159

In a letter to his friend, the publisher Ulrico Hoepli, dated 24 April 1947, Cerletti confided that, ‘In my leather bag, where I keep the urgent files, for months, there have been the drafts, now crumpled, of a lashing article against two French professors (Delay and Delmas–Marselet) who have appropriated my concepts’.Footnote 160 ‘The French … grab the intellectual priority of the Italians’, he insisted. ‘They have a good game because everyone reads French and no one Italian’.Footnote 161 Maybe this is why Lamberto Longhi defended his mentor in a report in French, arguing that Delay had started working on such topics only in 1943.Footnote 162 In 1942, Carlo Petrò at the University of Pavia was engaged in providing further evidence to Cerletti’s diencephalic localization, who he referenced, particularly through identifying changes in basal metabolic rate in electro-shocked schizophrenic patients. This was another local publication in Italian, though.Footnote 163

Notoriously, in 1952, Jean Delay made advancements that Ugo Cerletti, with acroagonines, could not. Delay presented seminal experimental work with Pierre Deniker at Saint-Anne’s Hospital in Paris, presented in six renowned papers,Footnote 164 which hailed the introduction of the first effective neuroleptic, chlorpromazine (CPZ), to psychiatry. At the time, the tensions between Cerletti and Delay had already been solved.Footnote 165 They, then, will share the frustration of not getting a Nobel Prize for their respective psychiatric achievements, ECT and CPZ.Footnote 166

Psychiatric application of this phenothiazine amine product, a synthetic antihistamine originally prepared as an insecticide by entomologists and chemists for the US Department of Agriculture, was the outcome of work started at the French company Rhône-Poulenc from fall 1950.Footnote 167 Ignoring previous null findings by American researchers,Footnote 168 which similarly sought to prove the antimalarial effects of this compound, chemically close to a synthetic antimalarial agent (i.e. methylene blue), Marc-Antoine Charpentier and collaborators at Rhône-Poulenc began testing it for malaria, though they ended up classifying it as a potentiator for general anaesthesia. Before Delay and Deniker, the navy surgeon Henri Laborit, during research on artificial hibernation, had tested it on a severely agitated manic patient aged 24, Jacques Lh., at the military hospital Val de Grâce in Paris. Laborit’s patient received CPZ with ECT and two other drugs, an opiate (peditine) and a barbiturate (penotal).Footnote 169

Notably, CPZ was found to work as antipsychotic medication. Yet, the psychiatric research on CPZ was greatly associated with ECT, even if ECT was (and still is) indicated for severe depression.Footnote 170 Cerletti celebrated these achievements, claiming that chlorpromazine and reserpine had ‘revolutionised the life of psychiatric institutions’.Footnote 171 Before, he had been attracted by Arthur Sackler’s work on histamine therapy for mental conditions, a psychiatrist who in 1949 had focused on cortisone and ACTH as well.Footnote 172

In psychiatry, CPZ became popular for its secondary properties, as it affected ‘a high degree of ‘central’ [brain] activity regardless of antihistaminic activity’.Footnote 173 These central brain effects (sedative, analgesic, hypothermic) of a synthetic antihistamine – especially sedation, the most clinically significant – could have been confirmed in animal models (i.e. rats) in the fall of 1947. Curiously – and this catches our attention – it was the insight that CPZ affected the diencephalon that drove Jean Delay to test this compound in psychotic patients. In their early work, Delay and colleagues claimed explicitly they were looking for ‘treatments likely to act by mechanisms inverse to those caused by shock methods’, analogizing to the idea of an alarm reaction, and that they had been attracted by Laborit’s method of affecting the vegetative system.Footnote 174 Delay and Deniker’s novelty was that they ‘administered chlorpromazine alone, with no other drug in combination’, and in doing so, they proved it successful.Footnote 175 More importantly, the link between CPZ and the diencephalic model was offered by theories about the action mechanisms of ECT. These were proposed to be localised in the hypothalamus from the neurovegetative effects observed and measured in the post-shock phase,Footnote 176 a notion that Delay supported with the findings of his experimental work in 1943,Footnote 177 and that he had defended theoretically in his 1946 book.Footnote 178 Ten years later, the diencephalon would go on to gain attention in international psychiatry.Footnote 179

Certain authors have claimed that ‘Cerletti’s effort was particularly interesting from a theoretical point of view because it was directly influenced by Delay’s writings on the diencephalon’.Footnote 180 This narrative, opposed by some Italian scholars as soon as the 1960s,Footnote 181 contrasts with the aforementioned details from Cerletti’s archival and bibliographic records. That, on the diencephalon theory, Cerletti preceded Delay by 6 years, but that the latter was ‘evidently unaware of Cerletti’s explanation’,Footnote 182 was instead the interpretation put forward by Paterson in The Lancet in his 1948 article.

We may doubt that Delay was oblivious to Cerletti’s theory – as in his 1946 book Delay actually referenced Cerletti’s 1940 work at one point, mentioning Cerletti’s association of electric epilepsy with a terror-defence reactionFootnote 183 – but at no point did he explicitly acknowledge Cerletti with regard to the diencephalic hypothesis, a core point of Delay’s book. On the flip side, Cerletti claimed that Delay was ‘perhaps the only one who has read it [Cerletti’s 1940 work] thoroughly’.Footnote 184

There are many points of convergence between Cerletti and Delay’s theories on the diencephalon. Frequent overlaps of bibliographic sources may simply be a sign of the psychiatric knowledge of the time but the two also shared the association of the diencephalic effects of ECT with humoral and hormonal reactions,Footnote 185 along with a theory of consciousness.Footnote 186 As Cerletti noted:

1940 – ES is not an electrical treatment – elect[ricity] is only a stimulus – it is a treatment of diencephalic stimulat.[ion] that takes place by means of the epileptic attack, especially by means of the humoral-hormonal discharge.

Prove it! Doussinet and Jacob blood. Blood is a too complex liquid, it summarizes too many metabolic processes, better to go to the source, the brain! Footnote 187

A neuroendocrine theory of mental conditions was not only the basis of Cerletti’s acroagonine theory but also the reflection of an interest he maintained from his early writings on the goiter. It seems that Cerletti was captured by the idea of an endocrine disequilibrium at the origin of the epileptic seizure, as he collected some 1935 publications in Italian reporting experiments on epileptic dogs, particularly through ablation of the pancreas and thyroid.Footnote 188 Cerletti used to define acroagonines as ‘hormonal–humoral biochemical reactions’, produced by the diencephalic neurovegetative system defensively, to safeguard animal life.Footnote 189 Besides this, it should be remembered that already, in 1932, Cushing had hypothesised a role of the pituitary–adrenal axis in depression, and ACTH had been isolated in 1933, with Kendall Reichstein then isolating cortisol a few years later.Footnote 190 Yet, Psychosomatic Medicine and The American Journal of Psychiatry, respectively, would acknowledge the role of ACTH in psychiatry with two dedicated journal issues only in 1949 and 1950.Footnote 191 Cerletti was interested in psychic effects of ACTH and cortisone,Footnote 192 and in experiments testing their effects at low dosages on epileptic children.Footnote 193

The idea of a humoral syndrome during ECT was said to have originated from blood research conducted before 1940 by Cerletti’s assistants Castellucci and Felici, who had, respectively, determined increased glycaemia levels and haematological modifications after ECT-provoked seizures.Footnote 194 These reactions were considered by Cerletti to arise from the nervous system, rather than due to the convulsive hyperactivity of the muscles, for example, from ‘exaggerated glucose combustion’. Cerletti noticed that Delay had advanced further ‘interesting considerations’ and findings, including those coming from EEG under ECT and direct diencephalic stimulation through pneumoencephalography, but he contested Delay’s idea that this humoral syndrome was also partially a result of the action of the muscles.

As for endocrine thinking, it is true that Cerletti was connected to a milieu of the time, particularly a revived interest in endocrine psychiatry, including experiments such as those with adrenal cortex extracts on schizophrenics in the late 1930s or with desoxycorticosterone acetate on catatonic patients in early 1940s.Footnote 195 Yet, Cerletti anticipated the later findings of many others with speculations for which he received no credit.Footnote 196 For instance, in 1951, based on the effects of ECT on the adrenal cortex, Max Reiss, Robert Hemphill, and colleagues proposed that depressed patients should be administered ACTH to stimulate the adrenal cortex.Footnote 197

In his 1940 speculations on acroagonines, Cerletti put forward an array of ideas that were developed years later, and some that are still debated nowadays.Footnote 198 The neuroendocrine theory of ECT, formulated by Max Fink and Jan-Otto Ottosson in the 1970s, followed descriptions by Bernard Carroll and Brian Davies of the dexamethasone suppression test, where dexamethasone suppressed ACTH and thus enabled an assessment of the levels of cortisol in the blood of depressed patients (so-called Cushing’s disease).Footnote 199 According to its defenders, neuroendocrine theory is sustained by a series of neuroendocrine abnormalities (e.g. release of ACTH, cortisol, and prolactin in the blood after hypothalamic stimulation via ECT). The theory serves both to explain endogenous depression and ECT’s action.Footnote 200 More importantly for the scope of this article, neuroendocrine theory was (and still is) ‘a viable theory that sees seizures as changing brain and systemic endocrine relationships, like Cerletti but unrelated to his image’.Footnote 201

Final remarks

The goal of this contribution was to present Ugo Cerletti’s audacious acroagonine research in a new, less-disqualifying light than before. The reconstruction offered herein was not intended to be exhaustive or conclusive though, and many questions remain for future historical investigations.

It was argued that with his research and theoretical insights, Cerletti paved the way for the development of psychopharmacology, whose explosion began after 1953, with the licencing of chlorpromazine on the market.Footnote 202 Looking beyond the diatribes between Cerletti and Delay on the paternity of the diencephalon hypothesis, this reconstruction emphasised that ECT, often seen as opposed to pharmacology, was a crucial step towards discovering psychotropic drugs. We must also take into account that Cerletti’s hypothesis of psychoactive substances in the brain was conceived before the experimental confirmation of the neurotransmitters and the identification of the biogenic amines in the mid-1950s and that of b-endorphines in the 1970s, which have been shown to be involved in ECT-induced physiological effects.Footnote 203 Cerletti’s claims were seen by his contemporaries to align with empirical findings that certain substances with the capacity for ‘pharmacological action’ on the vegetative neural system and on patients’ hormonal states had been identified through ECT research on dysthymic patients, though this substance ‘was not acetylcholine’.Footnote 204

Cerletti’s mistake was to have inferred the existence of acroagonines from the observed clinical effects without carrying out biochemical analyses.Footnote 205 The biochemistry of acroagonines remained his greatest concern,Footnote 206 and we may wonder whether this influenced his son Paolo’s choice of profession. Paolo became a biochemist in 1959Footnote 207; at the time, Ugo Cerletti was still ‘waiting, with the friendly collaboration of American biochemists, to determine the chemical formula of the acroagonines’.Footnote 208 He never expressed ‘any doubt about the existence of acroagonines’.Footnote 209

Seven years before the discovery of chlorpromazine, Cerletti was asserting that ‘it will be necessary, above all, to face [the problem of] the isolation of the active principles of acroagonines. I already said that’. ‘For this enterprise’, he claimed ‘the biochemists are asking us for new and safe tests, but we have seen that the biological tests available are slow and complicated. When the biochemists have given us the chemical formula or formulas of the acroagonines, they will perhaps be able to reproduce them by synthesis, and then we will not only have freed man from E.S. [electroshock], but also the animals’.Footnote 210 ‘For now, therefore’, he insisted, ‘we cannot answer the question about what these acroagonines are; but neither do we intend to venture into reasoning about their mode, or better their modes, of action in the various tests made on man and animals’. Nonetheless, as the following years would prove, he was wrong in his conclusions that, ‘We do not need to hurry; we must be satisfied, as we have been, with completely generic explanations’.Footnote 211

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to those who helped me with this research during the pandemic in 2020–21, especially Livia Castelli and Luca Tonetti, who established a preliminary inventory of the ES Section with me and commented on a previous draft. This work would not have been possible without them. I am truly grateful to Max Fink, Edward Shorter, Gilberto Corbellini, Paolo Mazzarello, Alessandro Aruta and Ruth Nielsen for insightful feedback. Neri Accornero, Maria Rosa Bollea, Cecilia Campedelli, Flavia Capozzi, Lidia Gomato, Giuseppe Longhi and Doriana Tomaselli kindly shared their memories. Maria Pia Bumbaca, Carlo Drago, Loredana Gitto, Carla Onesti, Salvatore Pagano, Giacomo Antonio Roseto at Sapienza University and Michael Church and Lauren Gray at the Kansas State Historical Society, assisted me incredibly in the access of the archival and bibliographic materials. I am thankful to Stefano Ferracuti and Carlo Drago at the Sapienza Human Neurosciences Department, and Maria Conforti at the Sapienza Museum of the History of Medicine, for giving me permission to publish the images contained in this article. Alessandro Aruta and Matteo Fiorani were also present when Ugo Cerletti’s archival materials in Rome were uncovered at the Sapienza Child Neuropsychiatry Section of the Human Neurosciences Library on 13 February 2019.

Funding

This work was supported by a 2019 Ateneum Project ‘Somatic interventions for mental conditions: a cross-cutting historical–philosophical investigation from research and clinical neuroethics’ at Sapienza University of Rome (RM11916B7993913E).

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.