On a blustery March morning in 2023, a coalition called #HandsOffDC held a rally outside Union Station in Washington, D.C. The rally was organized to protest Congressional interference in D.C. affairs. That afternoon, the U.S. Senate was scheduled to vote on a resolution nullifying D.C.’s revised criminal code.Footnote 1 A crowd of 200 protestors held signs that read “D.C. Statehood is Racial Justice,” “Hands Off D.C.,” and “Shame on faithless POTUS, rabid GOP, tyrannical Congress, and spineless Dems.” D.C.’s longtime delegate to Congress, Eleanor Holmes Norton, who serves in Congress without a vote, addressed the crowd.

We have come together today with one simple message for Congress and President Biden: keep your hands off D.C. You either support D.C. home rule or you don’t. There are no exceptions and there is no middle ground on D.C.’s right to self-government.

Norton went on to lambast D.C.’s lack of democratic equality:

What is happening in Congress is undemocratic. None of the 535 voting members of Congress were elected by D.C. residents. None of them are accountable to D.C. residents. Yet if they vote in favor of the disapproval resolution, they are choosing to substitute their policy judgments for the judgment of D.C.’s elected leaders. They will choose to govern D.C. without its consent. The nearly 700,000 D.C. residents, a majority of whom are Black and Brown, are worthy and capable of self-government (Norton 2023).

After the rally, supporters holding D.C. statehood signs marched to the Senate office complexes. 17 were arrested (Zets Reference Zets2023; Otten Reference Otten2023; Portnoy, Silverman, and Flynn Reference Portnoy, Silverman and Flynn2023). Nonetheless, the Senate voted 81-14-1 to nullify D.C.’s revised criminal code. Two days later, Speaker McCarthy held a raucous enrollment ceremony for the resolution in Statuary Hall.Footnote 2 President Biden signed the resolution into law on March 20, 2023, marking a low point in Washington, D.C.’s centuries-long quest for local self-governance and equal citizenship.

Washington, D.C. is a constitutional anomaly. Neither a state, nor a territory, the residents of D.C. are under the yoke of the federal government—all while lacking voting representation in the House, any representation in the Senate, and full local self-governance. Every word of D.C. code, down to its traffic laws, can be nullified by Congress; its federal taxes, imposed and spent by unaccountable, unelected super-legislators from the several states; its residents, though greater in population than several states, denied voting representation in the House and any representation in the Senate; its local crimes prosecuted by an unelected and unaccountable U.S. Attorney. That D.C., or “Chocolate City,” is plurality Black and majority non-white renders it an important edge case of American democratic principles. As Frederick Douglass once wondered, “what have the people of the District done that they should be excluded from the ballot box?” (Reference Douglass1895).

This article contributes to an ongoing scholarly conversation about D.C. and democracy. Recent scholarship has broken new ground in analyzing constitutional questions surrounding D.C.’s democratic status (Bulman-Pozen and Johnson Reference Bulman-Pozen and Olatunde2022) and in explicating the long fight for democratic governance in the District of Columbia (Masur Reference Masur2010; Pearlman Reference Pearlman2019; Musgrove and Asch Reference Musgrove and Asch2021; Sommers Reference Sommers2023; Kumfer Reference Kumfer2024). Building on this literature, this article makes three key contributions. First, the article situates the democratic status of D.C. as a live question throughout the tradition of American political thought. Various thinkers in that tradition, including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Frederick Douglass, Mary Church Terrell, Martin Luther King, Jr., Jesse Jackson, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Jamin Raskin, and more, have all considered the peculiar political status of the District, and connected D.C.’s status with American political ideals. Second, the article draws on democratic theory to sketch a case for D.C. statehood and autonomy. It imagines what the institutional consequences of democratic equality might look like both in Congress and in D.C. local government. Third, the article contributes to a burgeoning literature highlighting how the American polity has been shaped by a division between states and non-states in the federal system (Frymer Reference Frymer2017; Moore Reference Moore2017; Sparrow Reference Sparrow2017; Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr2019). The example of D.C. underscores how residents of Washington, D.C. and the U.S. territories lack equal standing in important respects to those living in the states—with profound democratic consequences.

The article proceeds as follows. First, I survey D.C.’s long history of democratic disenfranchisement. Second, I outline three principal forms of democratic disenfranchisement faced by D.C. residents: in its limited local self-government, votelessness in the House, and voicelessness in the Senate. Third, I present an argument that D.C. deserves democratic equality and respond to the most persuasive objections. Fourth, I imagine what democratic equality for D.C. would look like in practical terms. And last, I propose a broader research agenda about the democratic injustices accorded to Americans living outside the several states. In addition to Washington, D.C., the territories of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands are all located on the U.S. democratic periphery, and the residents of those territories also confront acute democratic inequalities. Political science ought to better confront the state-centered boundaries of U.S. politics, boundaries which create an enduring inequality between states and non-states in American democratic life.

The Historical Development of Democratic Inequality in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C. is a jurisdiction unlike any other in the United States. The Constitution gives Congress plenary power “to exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States.”Footnote 3 Uncontemplated in this so-called “District Clause” is the status of those persons who live in D.C., a problem that continues to dog Washington D.C. today.

In Federalist No. 43, James Madison argues that exclusive federal control of the federal district is necessary. A federal capital, he argues, would prevent “a dependence of the members of the general government on the state comprehending the seat of government” (Carey and McClellan Reference Carey and McClellan2001, 223). Madison feared the dependence of a federal capital on any given state. His apprehension dates to the young nation’s experience in 1783, when veterans from the Continental Army protested outside a Congress of the Confederation meeting in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia (Bowling Reference Bowling1977, 30–35; Gallagher Reference Gallagher1995). The so-called “Philadelphia Mutiny” pressured Madison, Jefferson, and Washington to give the nation’s capital a seat of government under federal, not state, control (Cobb Reference Cobb1995, 529–57). Even while insisting on federal control of the federal district, Madison also asserted the need for local self-governance for the residents of that district. As he wrote in Federalist No. 43, the inhabitants of the federal district “will have had their voice in the election of the government, which is to exercise authority over them … a municipal legislature for local purposes, derived from their own suffrages, will of course be allowed them” (Carey and McClellan Reference Carey and McClellan2001, 223). His was an image of D.C. being nearly democratically equal with the states.

Indeed, from 1790–1801, eligible D.C. residents could vote for Members of Congress from Maryland or Virginia. In 1801, however, Congress passed the District of Columbia Organic Act, making D.C. the national capital—and depriving D.C. residents of any Representative in Congress (Raven-Hansen Reference Raven-Hansen1975, 174; Musgrove and Asch Reference Musgrove and Asch2021, 5–11). The Congressional debate over the Organic Act reflects the unease many felt toward stripping D.C. residents of their political voice. As Representative John Bacon said, “here the citizens would be governed by laws, in the making of which they have no voice—by laws not made with their own consent, but by the United States for them—by men who have not the interest in the laws made that legislators ought always to possess—by men also not acquainted with the minute and local interests of the place.”Footnote 4 In a pattern that would repeat itself again and again, Congress acted to curtail democracy for D.C.

Political power came to D.C. in fits and starts. In 1820, white male D.C. voters gained the right to elect the mayor directly. Their voting rights were quickly taken away, however, when Thomas Carberry, who favored expanding suffrage, was elected mayor. Fearful of overextending the vote, the city council passed a “hundred dollar law” restricting voting in D.C. to white men with substantial property. In 1830, Andrew Jackson became the first president to call for a nonvoting delegate seat for D.C.—to no avail.Footnote 5 Congress did not restore broader suffrage and lift the property-owning requirement until 1848 (Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017, 66). In 1846, Congress retroceded Alexandria County to the Commonwealth of Virginia, which gave newfound democratic rights to white men in Alexandria, while further cementing the slave power.

During the turbulent period leading to and during the Civil War, D.C. was a laboratory for national disputes over race and democracy. Slavery was abolished in D.C. in 1862 under the D.C. Emancipation Act, which provided payment to enslavers of $300 each “for each person shown to have been so held by lawful claim” (District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862, 12 Stat. 376 § 3). Black men in Washington gained the vote in 1867 with the passage of the District of Columbia Suffrage Act, a law passed over the veto of President Johnson and over the objection of nearly all white D.C. voters in a referendum on the question (Ingle Reference Ingle1893, 65; Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017, 141–46).

D.C. residents briefly had local democracy during Reconstruction, from 1871–1874. Under Mayor Sayles J. Bowlen, the city passed a law banning discrimination in places of public entertainment. Black D.C residents held positions as ward commissioners, firemen, and police. D.C. residents could also elect a nonvoting delegate to Congress. Norton P. Chipman, a Republican and ally of Frederick Douglass, represented the District as a delegate to Congress from 1871 until 1875 (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2014 [1935], 461–63; Whyte Reference Whyte1958; Masur Reference Masur2010, 214–56; Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017, 152–68). During his brief tenure, Chipman advocated for increased self-governance for the district. “I believe the people here,” he said, “are as competent to determine what is to their interest as the people of any other community.”Footnote 6 He also commented on the oddity of being a nonvoting member of Congress. Chipman viewed the role of nonvoting member as “peculiar … and totally distinct from that of a Representative in Congress who has a vote … . To be successful he must avoid antagonism in the House of Representatives, and bend his whole efforts to the measures immediately concerning his constituents.”Footnote 7

But the experiment in democracy for D.C. was not to last. Congress, outraged by profligate public works spending by the D.C. territorial government, revoked local self-government in D.C. in 1874. This decision ended D.C.’s experiment in local democracy and quashed Black political power (Piper Reference Piper1944, 90–133; Harrison Reference Harrison2006; Masur Reference Masur2010, 248–56). No longer could D.C. residents vote for their elected leaders; instead, the city would be managed by three appointed commissioners. “For the first time in its history,” Sam Smith writes (Reference Smith1974, 46), “the District became an unadulterated colony of the United States.” The District was not to regain limited local self-governance and nonvoting representation in Congress until nearly a century later (Musgrove and Asch Reference Musgrove and Asch2021, 165–68).

The treatment of Washington, D.C. bothered Frederick Douglass. Douglass, who late in life served as marshal and recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia, wrote about the “anomalous condition” of D.C. residents in his third autobiography.Footnote 8 As Douglass notes,

These people are outside of the United States. They occupy neutral ground and have no political existence. They have neither voice nor vote in all practical politics of the United States. They are hardly to be called citizens of the United States. Practically they are aliens; not citizens, but subjects. The District of Columbia is the one spot where there is no government for the people, of the people, and by the people. Its citizens submit to rulers whom they have had no choice in selecting. They obey laws which they had no voice in making. They have plenty of taxation, but no representation. In the great questions of politics in the country they can march with neither army, but are relegated to the position of neuters. (Douglass Reference Douglass1994 [1893], 960)

D.C. residents both live in the capital, yet also “outside of the United States” as Douglass points out. To be taxed without representation, to be bound by coercive federal laws for which no representative could vote, to be under the yoke of unelected and unaccountable federal officials—this is what Douglass means by “aliens; not citizens, but subjects.” The democratic problem Douglass identifies remains in place for Washingtonians today—the people living in the capital of a democracy “have no political existence,” governed by those who they did not elect and bound by laws to which neither D.C. residents nor their elected representatives had any ultimate say.

For nearly a century, D.C. residents lacked any vote whatsoever, a political situation which disenfranchised scores of Black citizens. “Surely nowhere in the world do oppression and persecution based solely on the color of the skin appear more hateful and hideous than in the capital of the United States,” wrote Mary Church Terrell, “because the chasm between the principles upon which this Government was founded, in which it still professes to believe, and those which are daily practiced under the protection of the flag, yawns so wide and deep” (Reference Terrell1907, 186). Unlike the territories in the contiguous United States that typically became states under the provisions of the Northwest Ordinance, D.C. remained in limbo.Footnote 9 The failure of Congress to grant D.C. statehood was in line with broader partisan and racial logic central to the statehood process.Footnote 10

It wasn’t until 1961 when D.C. residents gained the right to vote for president and vice president with the ratification of the Twenty-third Amendment. The Twenty-third Amendment was only a partial expansion of political rights for D.C. residents, however. Because D.C. is not a state, its residents lack equal power to vote for president. The amendment’s original Senate-passed language would have provided D.C. with the same number of electors as if it were a state, but a House amendment changed that language to specify the number of electors be “in no event more than the least populous State.” In practical terms, this reduced D.C.’s voting power from five electors to three in 1964, giving it unequal political power in the selection of the president compared with the states of equivalent population (McMurtry Reference McMurtry1977, 15–18).Footnote 11 According to the Washington Post, the stipulation limiting D.C.’s electors to that of the least populous state was part of an “unspoken bipartisan reluctance to grant broader suffrage to a city with a Negro majority” (Mintz Reference Mintz1960). No Southern or border state ratified the Twenty-third Amendment except Tennessee (Derthick Reference Derthick1962, 73–74).Footnote 12

The Twenty-third Amendment provides only incomplete power for D.C. residents to select the president. Its passage increased the total electoral votes from 535 to 538, making a tie in the electoral college possible—yet if there is a tie, Washington D.C. would be excluded from the contingent election to select the president and vice president (U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, cl. 3; see also Neale Reference Neale2020, 14). If there are objections to the counting of electoral votes from one or more states or from the District of Columbia, D.C.’s delegate is unable to vote on objections to the counting of electoral votes under the Electoral Count Act (3 U.S.C. § 15). D.C. is also structurally excluded from determining qualifications for office. Under Trump v. Anderson 601 U.S. 100 (2024), Congress (consisting of Representatives and Senators—not Delegates) retains exclusive power to enforce the insurrectionist qualification (Fourteenth Amendment § 3). In all these ways, while D.C. residents may vote for president, their power to select the president is structurally inferior to the residents of the several states.

Short of statehood, D.C. lacks broader powers granted to states and their elected representatives. It cannot ratify constitutional amendments, even amendments that directly affect D.C. residents (U.S. Const. art. V). It has no say in admitting new states into the Union (U.S. Const. art. IV, § 3, cl. 1). As I show next, it is dogged by three key structural inequalities that stem from its non-state status under the Constitution—in its local government, the House, and the Senate.

Three Forms of Contemporary Democratic Inequality

In this section, I outline three principal forms of democratic inequality faced by D.C. residents. It is worth noting at the outset that D.C. residents have continuously made their demands by invoking the American democratic tradition. In the March 2023 rally at Union Station, Eleanor Holmes Norton argued that those members of Congress who legislate on D.C. without giving D.C. a vote “choose to govern D.C. without its consent” (Norton 2023).

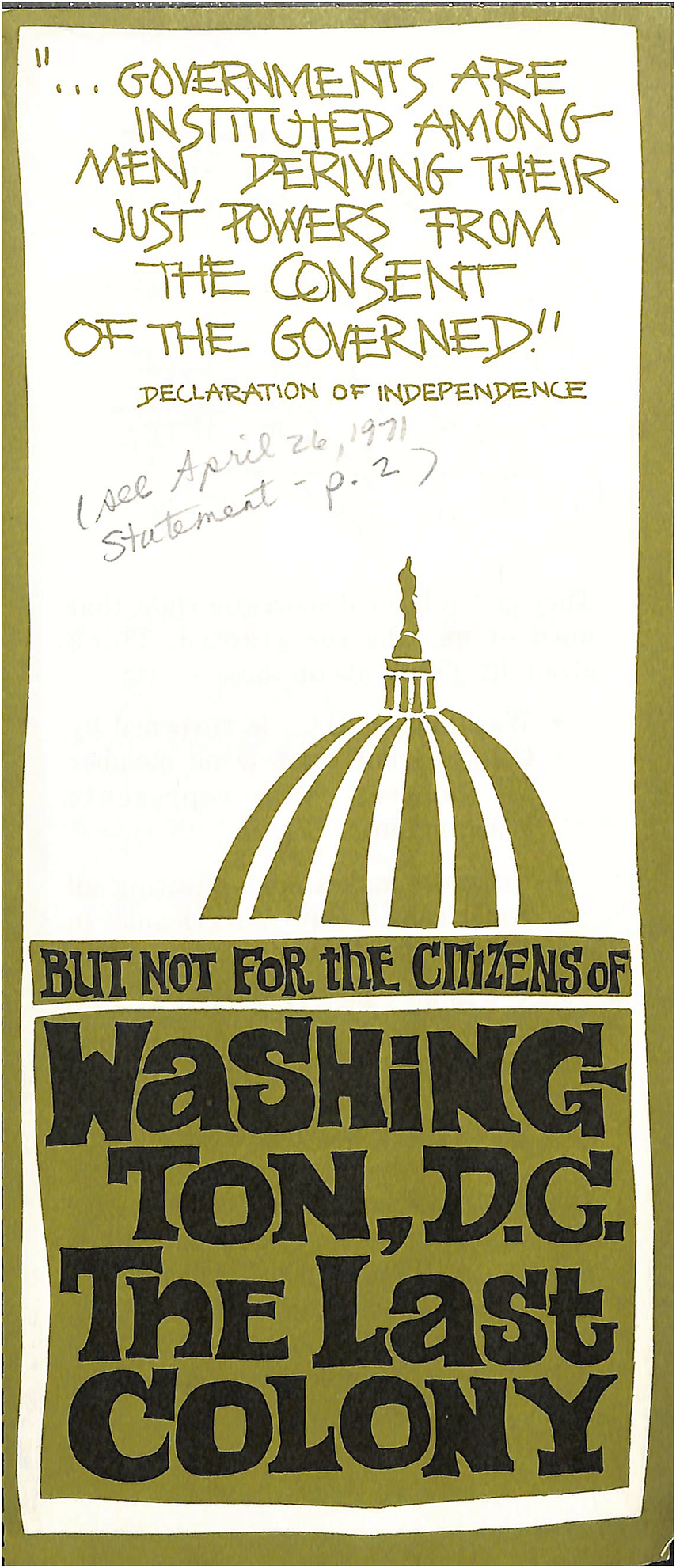

Figure 1 League of Women Voters brochure, circa 1970s

Source: League of Women Voters Brochure, circa 1970s. In the National Archives, Washington, D.C., RG 233, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, 93rd Congress, Committee on the District of Columbia, Box 22 - Legislative Files, H.R. 9056, H.R. 9598, H.R. 9617, Folder - Home Rule Documents Pre-1973, Incl. Hoover.

For those residents of the several states, some kind of democratic say, however partial, is proffered through periodic elections whereby voters choose in competitive elections who will represent them as a lawmaker. By contrast, D.C. residents are unable to elect voting members of Congress who can, in a formal sense, have a say in what the law is. The residents of the several states and territories, with exceptions, also have full local self-government.Footnote 13 The residents of D.C. do not. Local laws enacted by their duly elected local government can be nullified by an unelected and unaccountable Congress. These deficiencies, alongside D.C.’s limited self-government and second-class status in Congress, render the status quo a suboptimal solution to D.C.’s democratic deficit. I expand on these democratic deficiencies in the following section.

D.C.’s Home Rule: Limited Self-Government

Congress granted D.C. limited home rule in 1973 when it passed the District of Columbia Self-Government and Governmental Reorganization Act (Fauntroy Reference Fauntroy2003, 40–58; Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017, 376–82; Pearlman Reference Pearlman2019, 200–202). The passage of that law, commonly known as the Home Rule Act, was a major victory for the civil rights movement. During a visit to the District, for example, Martin Luther King Jr. had urged an “all-out nonviolent movement for home rule,” saying that “You don’t have freedom in Washington … because you can’t vote.” He continued, “If you don’t know why they don’t want you to vote, I’ll tell you. It’s because the District of Columbia is 55 to 60 per cent Negro, and they know you will elect some Negroes to high public office” (New York Times Reference Times1965; see also Campbell and Shoenfeld Reference Campbell and Shoenfeld2021).

Home rule marked a high point of local autonomy for the District. It granted D.C. self-government for the first time since Reconstruction. Its passage was spurred on by the changing composition of Congress after the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which had increased the ability of Black people to vote in the South. Organized by Walter Fauntroy and other veterans of the civil rights movement, Black voters defeated John McMillan (D-SC), the openly bigoted chair of the House District Committee, propelling the House to pass a home rule bill, which was signed into law on December 24, 1973 (Mamet Reference Mamet2021, 400–404). Its passage was also spurred on by President Lyndon Johnson’s decision to grant D.C. an appointed City Council in 1967, by Congress’s creation of an elected D.C. school board in 1968, and by the 1968 violent unrest that decimated the city (Lester Reference Lester2003, 194–95; Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017, 351–54; Pearlman Reference Pearlman2019, 43–50; Sommers Reference Sommers2023, 157–59).

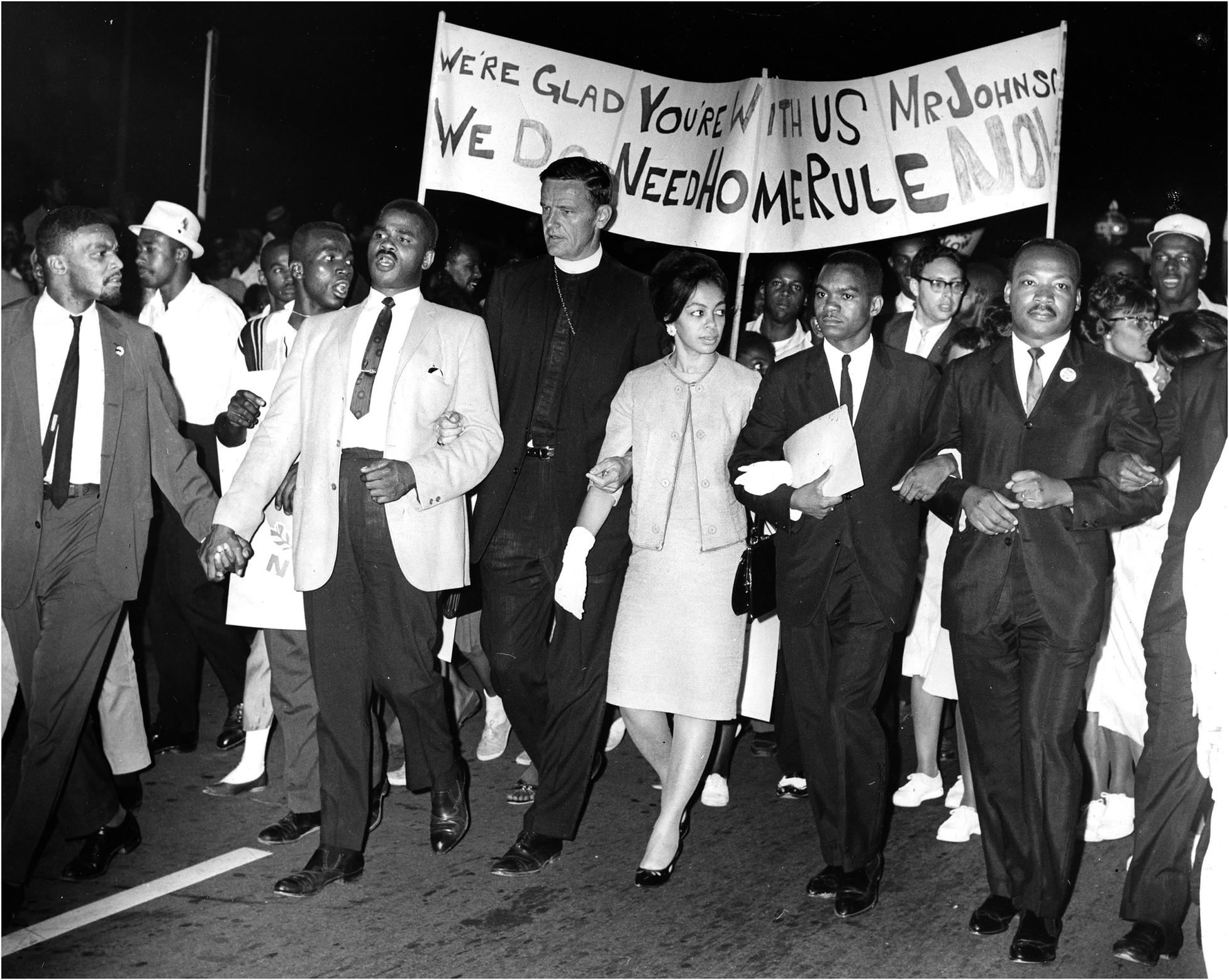

Figure 2 Martin Luther King Jr., Walter Fauntroy, Dorothy Simms Fauntroy, Paul Moore Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and Andrew Young (R to L) at the March for Home Rule, August 5, 1965

Source: Washington Star Photograph Collection, 061 (Washington, DC—Home Rule), DC Public Library, The People’s Archive. http://hdl.handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:117997. Printed in the Evening Star, August 6, 1965, B1. Reprinted with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection, Washington Post.

Yet the Home Rule Act was also a limited victory. The law specified that Congress “reserves the right, at any time, to exercise its constitutional authority as legislature for the District.”Footnote 14 The law also requires all enacted D.C. law to be transmitted to Congress for a period of 30 or 60 days, whereby Congress can vote on resolution to disapprove a D.C. law. Since the Home Rule Act was enacted in 1973, eleven separate disapproval resolutions have received floor consideration. Four were enacted into law (Jaroscak, Davis, and Leubsdorf Reference Jaroscak, Davis and Leubsdorf2024, 7–8).

D.C.’s limited local self-government exemplifies profound democratic inequalities. Disapproval resolutions, by nature, mark decisions about local D.C. affairs made by 535 legislators who are neither elected by nor answerable to D.C. residents. Beyond disapproval resolutions under the Home Rule Act, Congress interferes in D.C. affairs through authorization language which restricts or overturns D.C. law, and policy riders attached to appropriations bills, overriding D.C. law on issues ranging from abortion and needle exchange to traffic cameras and right turns on red. For example, in the first session of the 118th Congress, House Republicans attached an array of policy riders to the D.C. appropriations bill, including language banning marijuana legalization (the “Harris rider”), banning D.C.’s needle exchange program, and “prevent[ing] D.C. from prohibiting motorists from making right turns on red.”Footnote 15 Self-governance is contained in other important ways, too. Adult felonies in D.C. are prosecuted by an unelected U.S. attorney. Persons convicted of state-level offenses are not incarcerated in D.C. but instead housed in federal Bureau of Prisons facilities across 33 states (Cooper Reference Cooper2018). The D.C. National Guard, unlike any other National Guard units, is under the direct control of the president, not the locally-elected D.C. mayor (Flynn and Brice-Saddler Reference Flynn and Brice-Saddler2021). The president may also federalize the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department (Hermann and Stein Reference Hermann and Stein2024). Even local zoning decisions are made by the National Capital Planning Commission, where most seats are not controlled by D.C. residents.

All three tools—disapproval resolutions under the Home Rule Act, authorizing language, and appropriations riders—are used by Congress to attempt to interfere in D.C.’s democratically-elected government. As one account put it, “throughout its history, the District of Columbia government has been changed, studied, supported, criticized, financed, debated, expanded, and reorganized—but all under the control of the U.S. Congress” (Thornell Reference Thornell1990, 1). It is a system of elections without power, or, more sharply, “participatory colonialism” (Smith Reference Smith1974, ix–x). Some 224 years after the enactment of the D.C. Organic Act, D.C. residents continue to lack the full right to govern their own affairs.

D.C.’s Delegate to Congress: A Voice without a Vote

D.C. residents may vote every two years on a delegate to the House of Representatives, a “seat in the House of Representatives, with the right of debate, but not of voting” (Pub. L. 91-405, § 202 (a)). The delegate has had the right to serve on Congressional committees, to serve in party leadership, and to sponsor and cosponsor legislation. During certain Congresses, they may vote in Committee of the Whole, among other procedural rights. And yet, the delegate has always lacked the critical legislative function: voting on the final passage of legislation (Hudiburg Reference Hudiburg2022; J.A. Smith Reference Smith2023, 403–6). Elected by those living outside the states, the delegates are charged to represent without a vote (Holtzman Reference Holtzman1986; Lewallen and Sparrow Reference Lewallen and Sparrow2018; Mamet Reference Mamet2021; Mamet and Bussing Reference Mamet and Bussing2024). On the range of roll call votes taken by the House—ranging from appropriations bills to impeachment, from authorizing of the use of military force to D.C. statehood, and even on federal tax rates for D.C. residents—the duly-elected D.C. delegate may not cast a vote. During votes on legislation, the delegate’s name appears on the electronic voting board above the press gallery, but the space next to their name indicating which way they voted always appears blank.

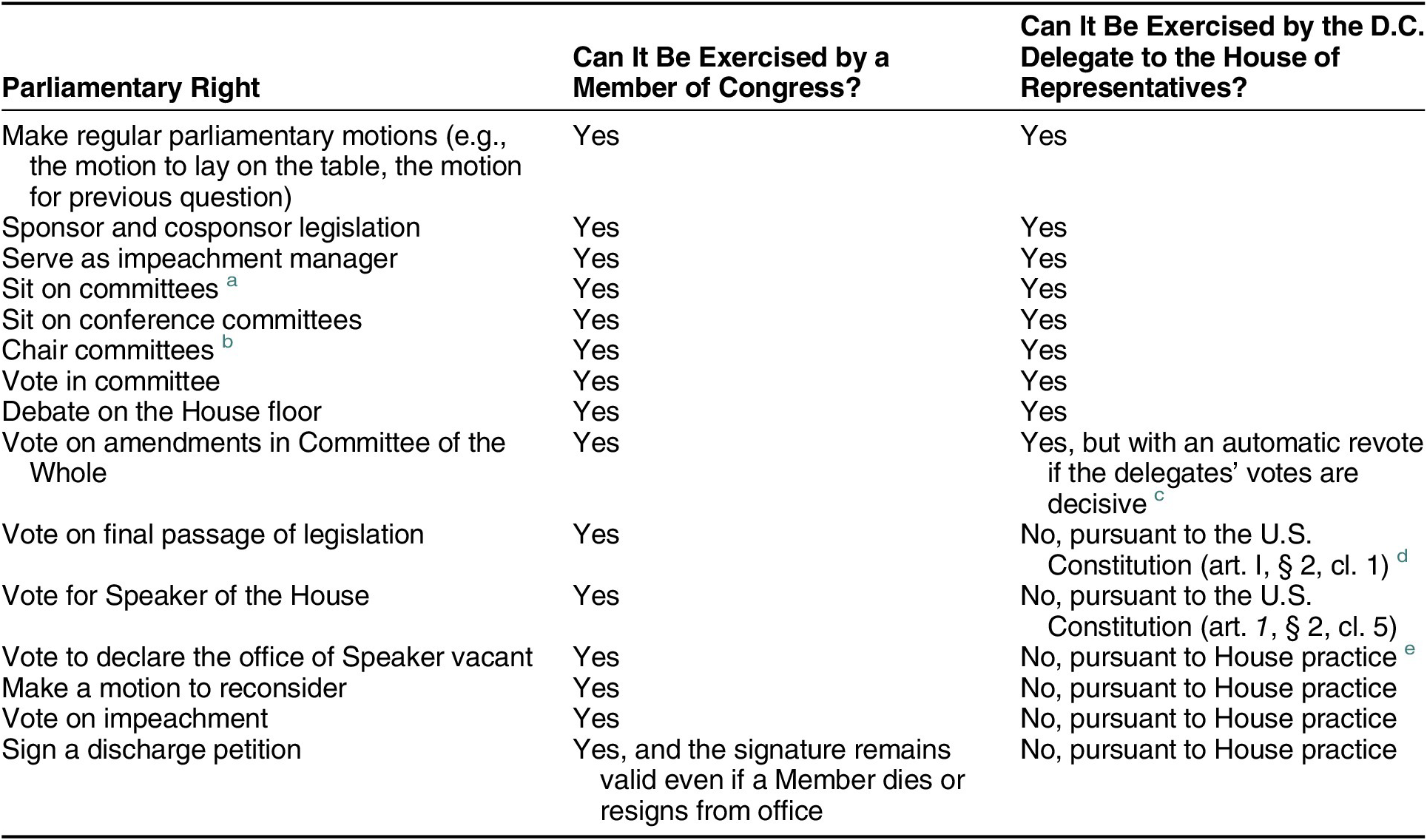

D.C.’s delegate occupies a procedurally inferior status compared to the 435 voting, constitutional members of Congress in numerous other ways. Voting members may vote for Speaker; the delegate may not, nor may they vote to oust a sitting speaker.Footnote 16 Voting members may vote to impeach; delegates may not.Footnote 17 Voting members can sign discharge petitions to bring legislation directly to the floor, and their signature remains valid even if they resign or die in office. The delegate cannot sign discharge petitions. (On this dimension, a resigned or deceased member of Congress retains more procedural rights than a nonvoting delegate.) A chart of key differences appears in table 1. Overall, a side-by-side view illustrates the extent to which the delegates’ parliamentary power is diminished compared to their 435 voting peers.

Table 1 The delegate’s second-class parliamentary powers

Notes:

a) Delegate Stacey Plaskett (D-VI) served as a manager for the second Trump impeachment.

b) However, no delegate in the modern era has been appointed to the Appropriations, Rules, or Budget Committees, and “party leaders typically assigned the delegates only to committees relevant to their local constituencies, and not to the power committees or other committees that grapple with broader national issues” (Lewallen and Sparrow Reference Lewallen and Sparrow2018, 746).

c) The last Delegate to chair a standing committee in Congress was William Henry Harrison in 1799 (Cama Reference Cama2022).

d) The D.C. Circuit affirmed this arrangement in Michel v. Anderson, 14 F.3d 623. A revote without the delegates has happened eight times—three times in the 103rd Congress, once in the 111th Congress, and four times in the 118th Congress (see also Hudiburg Reference Hudiburg2022, 2–3).

e) Numerous close votes on the House floor might have had a different outcome were the nonvoting members able to vote. In the 19th Congress, for example, Indian Removal was nearly defeated by a substitute amendment, which garnered a tie vote, 98-98. If that substitute passed, the Trails of Tears may never have occurred (Remini Reference Remini2006, 120; for other examples, see Mamet Reference Mamet2021, 409n42).

f) The delegates could not vote on the failed resolution to oust Speaker Joseph Cannon on March 17, 1910, nor on the successful resolution to remove Speaker Kevin McCarthy on October 3, 2023.

D.C.’s Absence in the Senate

D.C. residents lack any representation at all in the Senate, rendering them without a say in the ratification of treaties (U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2), impeachment trials (U.S. Const. art. I, § 3, cl. 6), and the confirmation of “Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officials of the United States” (U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2). They are unable to provide “advice and consent” (U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2) for the position of U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia (who prosecutes adult felony cases in D.C., an arrangement unlike any state) or on the confirmation of the federal judges, marshals, and other officials who preside in the District.Footnote 18 Moreover, D.C. residents have no senator who can assist with routine casework. D.C. residents are also unable to request Congressionally directed spending (or earmarks) from the Senate, depriving D.C. in “tens to hundreds of millions of dollars” each year to nonprofits, public works projects, and government agencies (Norton 2022). Likewise, without senators, D.C. residents cannot work with a bicameral state delegation in Congress (Treul Reference Treul2017). D.C. voters do periodically elect “Shadow Senators” and a “Shadow Representative,” whose duty is to lobby for D.C. statehood.Footnote 19 These roles are unpaid, and come without any recognition in Congress. The shadow delegation watches debate from the public galleries along with tourists, interns, and Congressional staff.Footnote 20

Beyond these formal inequalities, the lack of a Senate seat has profound implications for the District’s say in the national policymaking process. Central to its logic is equal representation for the several states (see Madison’s Federalist No. 62, in Carey and McClellan Reference Carey and McClellan2001, 319–24). The Senate’s grand symbolism reminds us of that logic, including the ornate pediment on the Dirksen Senate Office Building, which reads, “THE SENATE IS THE LIVING SYMBOL OF OUR UNION OF STATES.” Even though it is more populated than several states, even though its residents pay federal taxes and have served and died in every U.S. war, the residents of the federal district of Washington, D.C. are excluded from participation in the “Union of States.” D.C.’s Senate absence is emblematic of its formally inferior role in the American constitutional schema.

The Demands of Democratic Equality

I have tried so far to sketch the myriad ways by which the United States falls short of ideals of democratic equality for the residents of its national capital. D.C. residents are taxed without representation, bound by coercive laws passed by lawmakers they did not elect, sent to war their elected legislators could not declare, prosecuted by unelected prosecutors, voteless in the House, voiceless in the Senate, and unable to fully manage their own local affairs without Congressional interference. This section fleshes out the democratic problems raised by this peculiar political status. It outlines a positive vision for an alternative arrangement, rooted in theories of democratic political equality, and considers the most persuasive objections.

Political theorists of various stripes have identified the centrality of political equality to democratic politics. For example, Niko Bowie argues that “what has historically distinguished democracy as a unique form of government is its pursuit of political equality” (Reference Bowie2021, 167). There are several ways of conceptualizing what political equality entails. For theorists like Charles Beitz (Reference Beitz1989) and James Lindley Wilson (Reference Wilson2019, 75–95), political equality entails more than mere suffrage or equal formal political power. They argue for a capacious understanding of political equality, rooted, for instance, in a complex proceduralism or in the democratic deliberative process. While I am sympathetic to these views about the breadth of what political equality should require, on my account, the case of D.C. highlights how voting power should be seen as a necessary but insufficient condition for political equality.

Political equality should at a minimum, require equal voting power. That is, in a large representative democracy, consistent with notions of the equal political status of citizens, 1) one should be granted a vote for representatives in national and sub-national lawmaking bodies, 2) her vote should have equal weight to the votes of others, and 3) her elected representatives themselves should be empowered to have a vote on what the law is.

On all three domains, D.C. falls short of the requirements of equal voting power. First, for 1), the status of D.C. violates political equality because D.C. residents cannot vote for senators or for voting representatives, lawmakers who, under the plenary power granted Congress over D.C. in the constitution, make both federal and local law for D.C. residents. For 2), under the Twenty-third Amendment, D.C. residents only have equal weight in voting for president as residents of the least populous state, which has, at times, led to D.C. having fewer electoral votes than it would have had were it a state. For 3), laws passed by D.C.’s locally elected officials can be nullified by unelected, unaccountable members of Congress. D.C.’s locally elected officials are therefore not empowered to have a binding vote on what local law is. Likewise, D.C.’s delegate to Congress may debate but not vote; D.C.’s sole federal elected official is thus also not fully empowered to have a final passage vote on what the law is.

A few caveats. First, note here that my concern is limited to voting power. There are other violations of democratic political equality not related to voting such as standing for office (e.g., someone in Maryland or Virginia is able to run for governor or senator while a D.C. resident may not). Second, the standards of equal voting power are capacious. Taking ideals of democratic equality seriously might require rethinking the structure of the Senate altogether, where roughly the 578,000 citizens of Wyoming have equal voting power with some 39.24 million citizens of California, and rethinking the unrepresentative structure of the electoral college.Footnote 21 Were D.C. to become a state, D.C. voters would have greater voting power for Senate than all but the smallest states. For the purposes of my argument, we might say that the standards by which democratic equality should apply to D.C. are a non-ideal requirement of decreasing power inequality. Allowing D.C. residents to vote for two Senators, even if the votes of D.C. residents will have disproportionate weight compared to voters in California, is far preferable to disfranchising D.C. residents whole cloth.

It is worth pausing here to consider objections of the form that D.C.’s political inequality is justified, or at least tolerable. Four objections are considered. First, one objection would surmise that even if D.C. is formally politically unequal, efforts to enfranchise D.C. residents or grant the District equal political standing are in fact a partisan power grab by Democrats to gain extra votes in Congress (McLaughlin Reference McLaughlin2020). The equal voting power argument suggests that what matters is not, at base, the given partisan political valence of D.C. statehood, but instead the more basic need to have an equal say in collective self-government. Judith Shklar’s analysis of equality in American political thought is useful here. According to Shklar (Reference Shklar1991, 56), “the deepest impulse for demanding the suffrage arises from the recognition that it is the characteristic, the identifying, feature of democratic citizenship in America, not a means to other ends.” Political equality for D.C. would be desirable even if it didn’t lead to Democratic electoral gains.

A second, more persuasive objection states that D.C. residents seeking full representation and equal political standing can easily move to nearby jurisdictions like Maryland or Northern Virginia, thereby becoming enfranchised and gaining the privileges coming with living in a U.S. state. As Chip Roy (R-TX) once put it: “They could vote with their feet. They could move into Maryland. They could move to Virginia. They could be in another location. That is fine.”Footnote 22 Indeed, compared to persons moving around the world to escape repressive regimes and gain freedom, the cost of moving across the river (or even across the street) from D.C. to its neighboring jurisdictions may seem small.

There are several possible responses to this “foot voting” objection. For one, moving costs are higher than might first appear. There are indirect costs beyond the cost of physically moving, such as “the cost of parting with employment opportunities, family members who stay behind, and social networks” (Somin Reference Somin2020, 49). But indirect costs seem hard to quantify and harder still to generalize. A second, more persuasive response is one of fairness. For D.C. residents who already are treated as democratic unequals, persons who pay income tax without voting representation and who lack full local self-government, it seems like a disproportionate burden to need to move to gain democratic equality. The costs of this move will be unfairly wrought by those already treated as second-class citizens. But above all, the “foot voting” objection obfuscates all those people who cannot move and will remain. The diminished political status of D.C. residents will persist so long as there are any people living in the District.

Third, some have argued that D.C. has more than adequate virtual representation in Congress. Rep. Benjamin Hardin (KY) asserted in 1835 that “the people here [in D.C.] have more weight in this House than the representatives of any State in the Union. The members of Congress associate with them, partake of their hospitalities, and lend a kind ear to their importunities.”Footnote 23 Frederick Douglass also gestured toward this objection in an 1877 address:

There has of late been much complaint of this discrimination against the people of the District. But the injustice is, as was foreseen by the fathers of the Republic, more seeming than real … . What they have lost by their exclusion from the ballot box is more than made up to them by their contact with the men who make the laws and administer the Government. Legislators, judges, and executive officers naturally enough desire to stand well with their neighbors, and they are seldom so inflexible as not to yield something to accomplish this result. (Douglass Reference Douglass, Blassingame and McKivigan1991 [1877], 457)

A century later, Senator Orrin Hatch made a similar argument:

The problems, needs, and concerns of the District, unlike those of Wichita or Dubuque, inevitably come to the attention of nearly all members of Congress through District radio, television, and newspapers … . The typical letter-to-the-editor read by Senator Smith on Sunday morning is far more likely to be from a GS-15 bureaucrat at the Department of Energy than from a pharmacist in Laramie, Wyoming. (Hatch Reference Hatch1978, 521)

This objection confuses proximity for accountability. No matter how close D.C. residents may live to the Capitol, no matter how much contact they have with lawmakers, those lawmakers seek re-election not by D.C. residents but by voters in their district. It is not D.C. residents who can hold lawmakers from Kentucky or Maine accountable for their actions on D.C. policy issues, but rather the voters of those states.Footnote 24

Fourth, some point to the desires of the Founders to have an independent federal district, “separate from, and not dependent on, any State” (Baker Reference Baker2015). Under this objection, the federal nature of the U.S. system requires a capital city that is under plenary federal control. It requires, in other words, a city that is for all the nation—and a city governed collectively by the nation. There is indeed a unique federal interest in D.C. affairs. That federal interest that would be retained under D.C. statehood with the creation of a small federal enclave consisting of the National Mall, White House, Capitol Building, Supreme Court, and adjacent federal office buildings.Footnote 25 The federal government would retain plenary authority over that federal area. Yet outside this enclave, in the city of Washington beyond the marble and monumental, the federal interest would give way to the democratic interest of local self-government. D.C. statehood would mean that neighborhood parks would be managed by a local parks department, not the National Park Service; local crimes would be prosecuted by a locally elected attorney general, not an unelected U.S. Attorney; zoning decisions would be determined by the local community, not a federal board with limited D.C. representation. The argument, in other words, concedes that there is an important federal interest in the governance of D.C., but contends that federal interest should be limited to a federal area. Maintaining a federal interest need not yield a permanently disenfranchised class of Americans.

One way to view the cause of D.C. statehood is through the long sweep of democratic changes to the U.S. constitution. The quest for democratic equality for D.C. residents echoes the country’s gradual expansion of suffrage through the Fifteenth, Seventeenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-third, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-sixth Amendments, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and in various constitutional evolutions which supported equal voting power. The expansion of suffrage has of course fallen short in crucial ways (Keyssar Reference Keyssar2000; Dilts Reference Dilts2014; Weare Reference Weare2017; Hasen Reference Hasen2024). But this history also suggests that within the American political tradition exists a powerful case for democratic equality—an idea that we all deserve equal voting power to shape our democratic future. D.C. statehood would contribute to that vision of the American polity. As W.E.B. Du Bois once wrote, “if America is ever to become a democracy built on the broadest justice to every citizen, then every citizen must be enfranchised” (Reference Du Bois2007 [1920], 71).

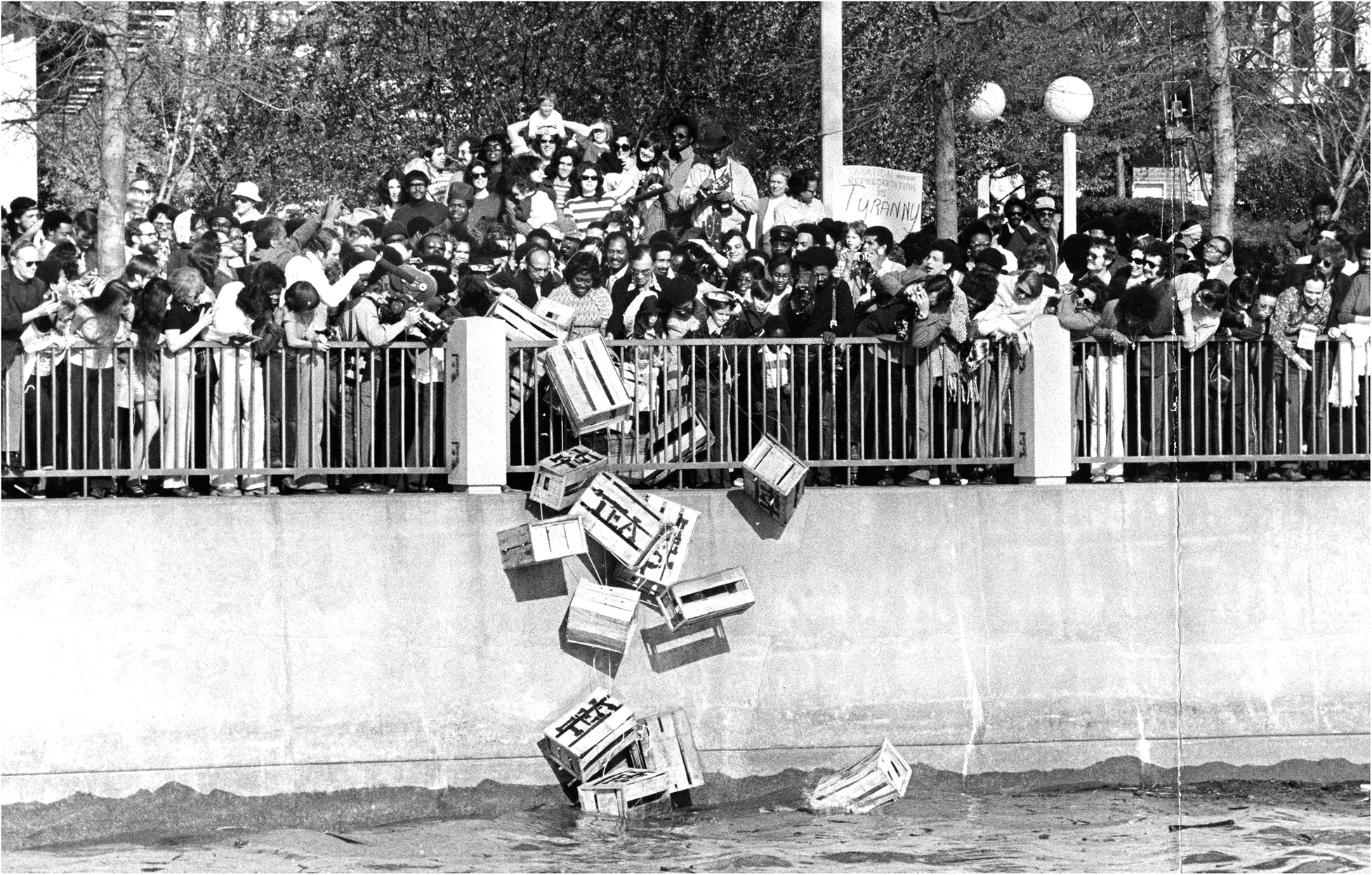

Figure 3 Members of Self Determination for D.C. dump tea crates into the Potomac River, 1973

Source: Washington Star Photograph Collection, 061 (Demonstrations - Home Rule - Oversized), DC Public Library, The People’s Archive, http://hdl.handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:118008. Printed in the Evening Star, August 16, 1973, D3. Reprinted with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection, Washington Post.

Achieving Democratic Equality

From the perspective of equal voting power, statehood remains the best strategy to achieve political equality for the people of Washington. It would grant D.C. residents voting members of the House and Senate, who would have equal voting power in national decisions, and elected local officials whose votes on local laws would be binding, absent interference by unelected lawmakers from elsewhere. It would be irrevocable, unlike statutory schema for limited self-government or nonvoting representation in Congress (Smith Reference Smith1974, 270–74). It would grant D.C. “equal footing” with the several existing states under the Admissions Clause (U.S. Const. art. IV, § 3, cl. 1; see also Hanna Reference Hanna1951, 522–24; Barnes Reference Barnes2010, 4). It thereby complies with a minimum requirement for political equality.

Advocacy for D.C. statehood dates at least to 1893, when labor leader A.E. Redstone formed a Home Rule Committee to call for a state of “Columbia” (Musgrove Reference Musgrove2017, 5). It persisted in the radical activism of statehood advocates like Julius Hobson and Josephine Butler, who succeeded in pushing a onetime fringe issue into the mainstream (Smith Reference Smith1974, 256–65; Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017, 378; Pearlman Reference Pearlman2019, 195; Kumfer Reference Kumfer2024). Yet the struggle for statehood has been arduous for the people of D.C. As Derek Musgrove notes, “statehood activists have consistently failed to advance the cause” (Reference Musgrove2017, 4). At turn after turn, the quest for statehood has been stymied by an obstinate Congress, by partisan political calculations, and by disinterested elected officials.Footnote 26 Opponents have argued that it would give federal employees and advocates of “big government” too much power.Footnote 27 Statehood has been long stymied by racial animus and anti-Black racial attitudes (Nteta et al. Reference Nteta, Rhodes, Wall, Dixon-Gordon, La Raja, Lickel and Mah2023; Horne Reference Horne2023, 510).Footnote 28 D.C. residents voted 86% for statehood in 2016. In Congress, a statehood admission bill passed the House in 2020 and 2021. But the uphill battle remains, and the obstacles are large. Robinson Woodward-Burns (Reference Woodward-Burns2021) writes that “the history of the D.C. statehood movement has been one of incremental gains against entrenched congressional opponents and constitutional constraints.” In its absence, other options remain for reducing the political inequality Washingtonians face with their fellow citizens.

One option is retrocession. Retrocession would cede D.C. (except a “federal district” consisting of the Capitol down to the White House) to the state of Maryland. Retrocession is an old idea, proposed as early as February 8, 1803, by John Bacon of Massachusetts.Footnote 29 Upon introduction, John Smilie of Pennsylvania endorsed the idea, saying that “under our exercise of exclusive jurisdiction the citizens here are deprived of all political rights … if Congress can derive no solid benefit from the exercise of this power, why keep the people in this degraded situation?”Footnote 30 But after much debate, the retrocession resolution was defeated in the House by a vote of 26–66.Footnote 31

Amid the push for D.C. statehood in the last three decades, retrocession has been a popular approach especially favored by Congressional Republicans.Footnote 32 It was considered on the floor of the Senate in 2009, and defeated 30–67.Footnote 33 On its face, retrocession would solve many injustices afforded D.C. residents: it would give them voting representation in the House and Senate and full local self-government, granting them equality among people of the several states. While it may advance certain forms of democratic equality, retrocession would violate the express wishes of D.C. residents (86% of whom voted for statehood in a 2016 referendum) and Maryland residents (who are overwhelmingly opposed to retrocession in public opinion polls; see McCartney and Clement Reference McCartney and Clement2019). Elected officials in both jurisdictions also strongly oppose retrocession, and neither jurisdiction would assent to D.C.’s retrocession to Maryland.Footnote 34 Put otherwise, retrocession may indeed increase the democratic rights of D.C. residents—but it would do so in an undemocratic way.

In the absence of statehood or of retrocession, other suboptimal options exist to mitigate the democratic inequality afforded D.C. In terms of D.C. local affairs, Congress could amend the Home Rule Act to grant D.C. full local self-government, unlike the partial self-government it enjoys today. Congress could remove the Congressional review period for D.C. legislation.Footnote 35 It could provide D.C. the power to legislate on any matter not preempted by federal law (Hanson and Wolman Reference Hanson and Wolman2023, 295). It could allow D.C. residents to choose the size and structure of its Council. It could allow D.C., not the president, to select its own local judges. While numerous changes to home rule would enhance D.C.’s autonomy, however, they all leave the District in an unequal status. As representatives of the D.C. Statehood Party argued in 1973, “so long as Congress retains some kind of veto … there can be no real home rule. Elected district government officials would fear to take actions which antagonize the Congress, and therefore regardless of many times Congress actually exercises a veto, they will in effect have pre-vetoed much legislation.”Footnote 36 Home rule without statehood still renders D.C. residents democratically unequal compared to the citizens of the several states.

In the House, rules changes could enhance the procedural power of the delegate. To return to table 1, this would entail granting the D.C. delegate procedural powers currently prohibited by House practice. For example, the delegate could be granted the right to sign a discharge petition. The discharge petition is a device by which a majority of House members may bypass the committee of referral to bring a measure directly to the House floor. Currently, delegates may vote to report a measure from a committee, and they may vote to amend a measure in the Committee of the Whole, but they may not sign a petition to discharge a measure from a committee. Allowing the delegate to sign discharge petitions would put the discharge rules into accordance with earlier rules changes that allow the delegate to vote to report measures out of committee (Hudiburg Reference Hudiburg2022, 8–9).

The delegate could also be granted a vote on impeachment.Footnote 37 Although impeachment is a rarely used tool, it remains inconsistent that D.C. residents may vote for president (under the Twenty-third Amendment) but that their elected representative in Congress may not vote to impeach the president (U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 5). Without an impeachment vote for the D.C. delegate, D.C. residents become “the functional equivalent of partial citizens—good enough to vote for president, but not good enough to decide whether to remove him.”Footnote 38 The Twenty-third Amendment’s Enforcement Clause (“Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation”) provides constitutional support for granting the D.C. delegate in particular the right to vote on impeachment.Footnote 39

The delegate could also vote on a resolution declaring the Office of the Speaker vacant. The Constitution says that “the House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States” and that “the House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker,” (U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 1 and 5). Left unsaid is who retains the power to oust the speaker, and there is no apparent constitutional bar to allowing the delegate from D.C. a vote on that motion. As the Office of Speaker sat vacant for a week in January and later three weeks in fall 2023, some 700,000 residents of the District of Columbia had no floor vote about who that speaker would be, which had practical consequences for D.C.’s local governance.Footnote 40

There are other, more routine motions, too, on which the delegate could be permitted to vote, such as the motion to reconsider, a procedural device which allows the House to review its actions on a given proposal. Delegates could be permitted to vote on House rules or other simple resolutions, which are not law and only express the collective sentiment of the House (e.g., legislation entitled H.Res.). The Constitution offers no prohibition of these procedural expansions of the delegate’s power. Even though these reforms fall short of equal voting power (which can only come from statehood), they would nonetheless enhance the procedural rights of the delegate, and hence expand the formal powers afforded to D.C.’s elected delegate.Footnote 41

In the Senate, short of statehood, another option to reduce (but not eliminate) D.C.’s disenfranchisement is to award it a nonvoting Senate delegate position. While the nonvoting delegate to the House has a long history, dating to a committee chaired by Jefferson in the late eighteenth century, never has a nonstate entity or territory been awarded a Senate seat. The dreams of Washingtonians for a senator have been longstanding. Late in life, Frederick Douglass, who ran to be D.C.’s first nonvoting delegate to Congress, was reminded that while enslaved, he had hoped to be the first Black member of the Senate (Muller Reference Muller2012, 43–44). Nearly a century later, the House passed a D.C. Home Rule Act that included a provision awarding D.C. a nonvoting Senate seat. Wrote Senator Edward Kennedy (D–MA) in a letter to Senator Eagleton, “the designation of a nonvoting delegate to the Senate from the District of Columbia, offers the promise of providing an effective ‘in-house’ lobby toward the ultimate goal of full congressional representation in the Congress for the people of Washington. The non-voting Senate delegate is an appealing provision that I believe deserves to be maintained.”Footnote 42 Other advocates also supported the Senate delegate provision. Sterling Tucker and Richard W. Clark of the Self-Determination for D.C. Coalition wrote that “we strongly endorse the House bill’s provision for a non-voting D.C. delegate to the Senate.”Footnote 43 And yet, in conference committee with the Senate, the provision was dropped from the bill.Footnote 44 According to staffer Nelson Rimensyder:

At the opening of the House-Senate conference on the Home Rule Act, Senator Tom Eagleton (D-MO), Chairman of the Senate D.C. Committee, declared that the provision for a Senate delegate was not even on the table for discussion.

Shortly after the conclusion of the conference, I asked Senator Eagleton if he would consider holding hearings on the concept of a D.C. Senate delegate. His answer was an emphatic “No!” However, Senator Charles Mathias (R-MD), ranking Republican on the D.C. Committee at the time, told me he thought the Senate delegate idea was worthy of consideration by the Senate.Footnote 45

It still is. A nonvoting D.C. Senate delegate position would provide a modicum of voice from the nation’s capital to the Senate chamber. Even without a floor vote, that person could provide input on committees with jurisdiction over D.C. and on policy issues relevant to its citizens, request appropriations, and debate other Senate business, including executive and judicial nominations.

Short of statehood, changes to enhance D.C. home rule and strengthen congressional representation for District residents could enhance D.C.’s democratic standing, but one downside to these changes is that they could be rolled back at any time by Congress—just like in 1801 (when Congress ended congressional representation for D.C. residents) and in 1874 (when Congress revoked territorial government and the nonvoting delegate from D.C.) and in 1995 and 2011 (when the House removed the ability for the D.C. delegate to vote in the Committee of the Whole) (Hudiburg Reference Hudiburg2022, 2). Other options surely remain, too, each with merits and drawbacks. While it is worth considering inferior mechanisms which reduce D.C.’s political inequality and grant it greater standing in local and national governance, statehood ought to remain the only democratically acceptable political outcome. A grant of statehood is irrevocable; anything short of statehood is subject to the whims of Congress exercising its plenary power over the District.

Conclusion: “The Most Un-American Place in America”Footnote 46

I have tried here to defend the claim that equal standing as fellow citizens is incongruent with nonvoting congressional representation and curtailed local self-government. District residents are doubly disenfranchised. In Congress, they lack any representation in the Senate and their nonvoting delegate to the House has a procedurally diminished standing compared to the Representatives from the states. Locally, D.C. laws can be nullified by members of Congress who D.C. residents did not elect. Throughout D.C. history, racial animus and anti-Black racism have been at the core of its second-class political status (Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017). The residents of the District of Columbia, though guaranteed a bundle of constitutional rights accorded other citizens, are denied the wellspring of those rights—the vote.

D.C.’s democratic problem gestures toward a broader research agenda needed in political science about the state-centered boundaries of U.S. politics, a research agenda to study the profound inequality between states and non-states in American democratic life. This conflict has struck at themes of equality so important to American democratic ideals. William Riker (Reference Riker1964, 9) has written that “federalism is the main alternative to empire as a technique of aggregating large areas under one government,” but a study of the democratic politics in D.C. shows how institutions of federalism and empire are more coterminous than they might at first appear. The endurance of disenfranchised, sub-state anomalous zones like Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, places overwhelmingly home to racial and ethnic minorities who are bound by coercive, federal law on which their elected representatives may not vote, strains notions of political equality central to the American democratic ideal (Neuman Reference Neuman1996; Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr2019; Maass Reference Maass2020). Their endurance shows how, long after the passage of the Reconstruction Amendments, full citizenship in the United States is still tied to statehood (Bulman-Pozen and Johnson Reference Bulman-Pozen and Olatunde2022; more broadly, see Erman Reference Erman2018; Henning Reference Henning2023). These places represent a “break in the democratic fabric,” and it is right to call their political status paradigmatic for evaluating whether the American polity lives up to its own democratic creed (Raskin Reference Raskin1999, 41).

Hope for D.C., at least, is not lost. Statehood bills passed the House for the first time ever in 2020 and 2021. And were Douglass Commonwealth to become a state, its empowerment could spur a broader movement for democratic equality for those living outside the states, as well. As Raskin once wrote (Reference Raskin2014, 54), “a serious struggle for political equality in the District offers the most dramatic possibility for a democratic breakthrough not just for Washingtonians but for millions of other disenfranchised citizens in the fifty states and the territories and for all Americans, whose voting rights have proven to be precarious indeed.” Democratic equality demands, at a minimum, equal voting power across subnational domains. It behooves a country committed to ideals of self-governance and of democratic equality to extend those principles to the residents of its capital city and beyond.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Charles Beitz, Lucy Britt, Austin Bussing, Kai Yui Samuel Chan, Ingrid Creppell, Prithviraj Datta, Jihyun Jeong, Quinn Lester, Charles Nathan, Alex Noronha, Jerome Paige, Nathan Pippenger, Lucia Rafanelli, Loren Reinoso, Joseph Rodriguez, Volker Schmitz, Douglas Thompson, Robinson Woodward-Burns, anonymous reviewers, and audiences at the Association for Political Theory, George Washington University Political Theory Workshop, DC History Conference, and Midwest Political Science Association for comments and suggestions. Special thanks to the APSA Congressional Fellowship Program and to APSA staff members Meghan McConaughey and Nathan Bader. Research support was provided by the APSA Centennial Center’s William A. Steiger Fund for Legislative Studies.