Food insecurity in high-income countries is defined as a lack of access to a sufficient quantity and quality of food due to financial constraints(Reference Tarasuk1,Reference Alaimo2) . In Canada, household food insecurity is assessed in the regular cycles of the nationally representative, cross-sectional Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) using the eighteen-item validated Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM)(3). Based on the number of affirmative responses, households are classified into one of four levels of food insecurity: none (secure), marginal, moderate or severe(3). Marginal food insecurity reflects anxiety about food security or difficulty affording a quality diet, moderate food insecurity indicates compromises in either quantity and/or quality of food and severe food insecurity is characterised by significant restrictions in food intake and diet quality(3). In the 2017–2018 CCHS, 12·7 % of all Canadian households reported food insecurity, with 8·7 % in the moderate or severe categories, and 17 % of children were living in food-insecure households(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell4). Socio-demographic factors associated with household food insecurity in Canada include low income, low education, lone parenting and Black or Indigenous racial identity(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell4,Reference Tarasuk, Fafard St-Germain and Mitchell5) .

Food insecurity is associated with multiple negative physical and mental health outcomes, including increased rates of depression and chronic disease in adults and compromised psycho-emotional health and cognitive development in children(Reference Perez-Escamilla6–Reference Thomas, Miller and Morrissey8). Food insecurity during pregnancy is associated with poor maternal mental health and may be a risk factor for adverse birth outcomes and postpartum feeding practices(Reference Augusto, de Abreu Rodrigues and Domingos9–Reference Orr, Dachner and Frank11).

The Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP) is a federal initiative that aims to improve birth outcomes and breastfeeding among women facing increased health risks due to challenges such as poverty, social isolation, substance use and adolescent pregnancy(12). The CPNP serves over 45 000 women annually through approximately 240 community projects across the country(12). Although the CPNP’s goals do not explicitly include reducing household food insecurity, the programme does seek to improve participants’ access to nutritious foods. Core CPNP services include the provision of modest food supports or grocery gift cards in addition to group-based health and nutritional education and referrals to community supports. Given the CPNP’s aims, target population and the importance of food insecurity as a determinant of health, a more comprehensive understanding of food insecurity among CPNP participants is warranted.

In addition, there is a need for further investigation of the relationship between household food insecurity and infant feeding practices. Breastmilk uniquely supports human infant health and maturation, contributing to the foundation for a healthy life trajectory(Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros13). The World Health Organization and Health Canada therefore recommend that infants receive exclusive breastfeeding (only breastmilk and essential vitamins, minerals and medicines) for the first 6 months of life, with continued breastfeeding and complementary feeding to 2 years and beyond(14,15) . Qualitative evidence suggests that these recommendations can be challenging for food insecure families to meet, with high stress levels and concerns about maternal diet quality and quantity leading to sub-optimal breastfeeding practices despite strong beliefs in the benefits of breastmilk(Reference Francis, Mildon and Stewart16–Reference Gross, Mendelsohn and Arana18). Secondary analysis of CCHS data showed that respondents in food insecure households were no less likely to initiate breastfeeding, but were significantly less likely to exclusively breastfeed to 4 months postpartum compared with those in food secure households(Reference Orr, Dachner and Frank11). There is a need for prospective studies to further explore these relationships in vulnerable sub-populations at disproportionate risk of household food insecurity.

In this paper, we describe the prevalence, severity and predictors of household food insecurity in a cohort of birth mothers who registered prenatally in three CPNP sites in Toronto, Ontario. As a secondary objective, we also report associations between household food insecurity and breastfeeding practices to 6 months postpartum in this cohort.

Methods

Study setting and participants

This analysis utilised data pooled from two prospective studies (Studies A and B), which collected household food insecurity and infant feeding data from CPNP participants in Toronto. Both studies were conducted within a research programme examining opportunities for increasing vulnerable women’s access to postnatal lactation support through the CPNP. Participants were recruited prenatally from three CPNP sites: the Parkdale Parents’ Primary Prevention Project (5Ps), Great Start Together (GST) and Healthy Beginnings (HB) programmes. All of these CPNP sites primarily serve low-income and/or newcomer families. The population of the combined catchment areas of the three sites is approximately 180 000. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, all three CPNP sites operated as weekly drop-in programmes providing group workshops on perinatal health and nutrition topics as well as individual supports and referrals to address issues related to perinatal health, parenting and settlement. Snacks were provided at the drop-in programmes, and clients received a CAD$10 grocery gift card each time they attended. Participants at the 5Ps and HB sites also received a small hamper of groceries, and at the HB site, a hot-cooked lunch was served following the weekly CPNP programme. These additional food supports were provided with resources outside CPNP funding. In March 2020, in-person programming was suspended, but food hampers and/or grocery gift cards continued to be provided to registered clients at all three sites, with group workshops and individual supports provided by remote means to the extent possible within pandemic guidelines.

Detailed methods for both studies have been reported elsewhere, as have participant demographics and results for breastfeeding metrics(Reference Francis, Mildon and Stewart19–Reference Mildon, Francis and Stewart22). Study A examined the infant feeding practices of clients enrolled at the 5Ps CPNP site, which also implements a postpartum lactation support programme through additional charitable funds from The Sprott Foundation(Reference Francis, Mildon and Stewart19). Clients who registered in the 5Ps CPNP prenatally were eligible for the study; exclusion criteria were pregnancy loss and participation in a prior qualitative study. Recruitment for Study A began in August 2017, and data collection was completed in October 2020. Study A participants received a $40 grocery gift card on study completion. Study B was designed as a pre/post-intervention study investigating the effectiveness and feasibility of delivering postnatal lactation support based on the 5Ps programme model to clients of two other CPNP sites, the GST and HB programmes(Reference Mildon, Francis and Stewart20). All participants in Study A and those recruited to the post-intervention group in Study B, therefore, had access to free in-home visits from an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) with the provision of double-electric breast pumps as needed. Inclusion criteria for Study B were prenatal registration in the GST or HB CPNP sites and the intention to try breastfeeding and to continue living in Toronto with the infant. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy loss, preterm birth (< 34 weeks gestation), medical issues affecting infant feeding and hospitalisation of either the mother or infant at 2 weeks postpartum. Study B began enrollment in November 2018. Recruitment and intervention delivery were suspended in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but data collection for enrolled participants continued remotely until completion in September 2020. Study B participants received a $50 grocery gift card on study completion.

Data collection

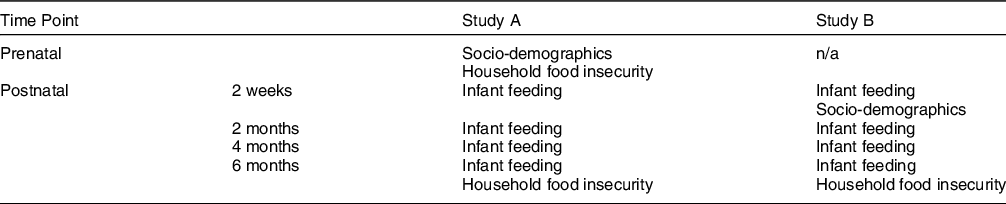

Data were collected either in person during the CPNP weekly programs or by telephone up to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and by telephone after that. JF conducted all data collection for Study A, using professional interpreters for participants who did not speak English (n 14). For Study B, data collection was conducted by AM or by a bilingual Research Assistant for Mandarin-speaking participants (n 39). Professional interpreter services were used for participants who did not speak either English or Mandarin (n 20). Table 1 provides the schedule for data collection in each study.

Table 1 Data collection schedule

In both studies, household food insecurity was assessed using the HFSSM and classified as none (secure), marginal, moderate or severe based on the number of affirmative responses(3). In Study A, the HFSSM was administered at 6 months postpartum with a 12-month recall period, and thus reflected household food insecurity status during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy as well as since the infant’s birth. In Study B, the HFSSM was administered twice: (i) prenatally, at study enrollment, capturing household food insecurity status over the previous 12 months and (ii) at 6 months postpartum to assess household food insecurity status since the infant’s birth.

Infant feeding data were collected prospectively in both studies at 2 weeks and 2, 4 and 6 months postpartum using the same standardised and validated interviewer-administered questionnaire(Reference O’Connor, Khan and Weishuhn23). At each time point, participants reported the average daily number of breastmilk and formula feeds their infant received during the past 2 weeks and whether any other fluids were provided. The dates of breastfeeding cessation and introduction of solids were reported where applicable. Participants were classified as yes/no for any breastfeeding and for exclusive breastfeeding at each data collection point, as described previously(Reference Mildon, Francis and Stewart22). Exclusive breastfeeding post-discharge for 4 or 6 months was determined by the number of consecutive time points at which participants were classified as exclusively breastfeeding. Hospital formula supplementation (yes/no) was recorded at the first postpartum contact and was considered an independent predictor of breastfeeding outcomes(Reference Semenic, Loiselle and Gottlieb24).

Maternal socio-demographic data were collected via interviewer-administered questionnaire and included maternal age (years); parity (primiparous, multiparous); education level (high school or less, post-secondary); years in Canada (< 3, ≥ 3 or birth in Canada) and ethnicity. Ethnicity was self-reported using a geographically based list developed and validated for a large Toronto-based birth cohort study, and the responses were then grouped into categories based on the region of origin(Reference Omand, Carsley and Darling25). Data related to household income were not collected in the same way in Studies A and B. Descriptive findings have been reported previously(Reference Mildon, Francis and Stewart22), and these data were not included in the current analysis. The HFSSM itself is an assessment of financial constraint.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for all indicators using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Frequencies for changes in household food security status and severity from prenatal to postpartum data collection were assessed for Study B participants.

In both Studies A and B, the HFSSM was administered at 6 months postpartum, but the reference time frames differed, as noted above. In order to mitigate any resulting misclassification of postpartum food insecurity, Study B participants whose household food security status changed from insecure prenatally to secure at 6 months postpartum (n 18) were excluded from the pooled dataset prior to analysis of the predictors of food insecurity and associations between food insecurity and breastfeeding practices.

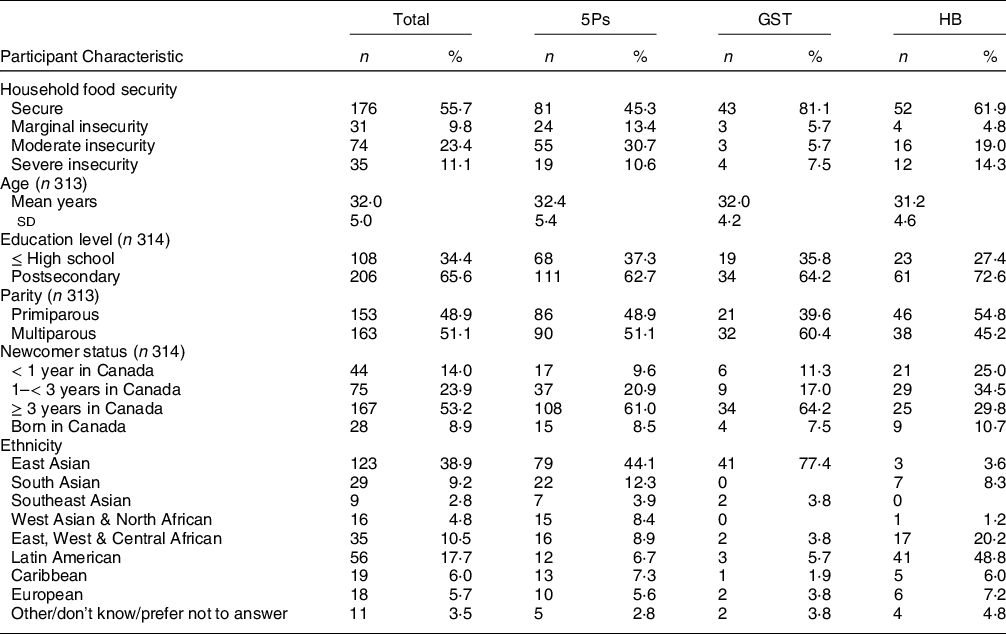

Predictors of any household food insecurity (yes/no) were examined first through bivariate screening of socio-demographic variables using chi-square tests for categorical variables (post-secondary education, birth in Canada, years in Canada, parity, CPNP site) and t tests for the continuous variable (maternal age). Ethnicity was not included due to the wide distribution of geographically based ethnicities within the sample (Table 2), resulting in insufficient sample size to detect differences accurately. Variables with P-values < 0·15 in bivariate screening were tested using multivariable logistic regression analysis. Prior to modeling, multicollinearity was assessed using tolerance statistics, with a tolerance value of < 0·4 as the cut-point. Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (P > 0·05) and AUC (> 0·7).

Table 2 Participant characteristics (n 316)

5Ps, Parkale Parents’ Primary Prevention Project; GST, Great Start Together; HB, Healthy Beginnings.

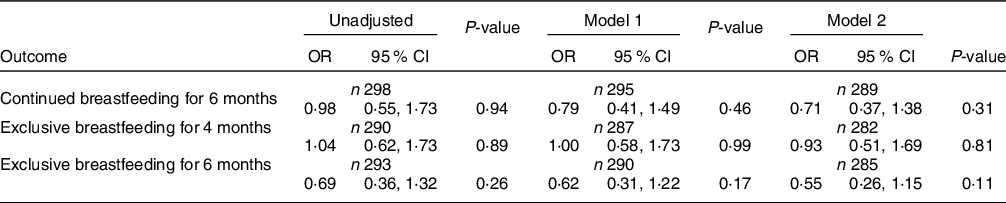

Associations between household food insecurity and breastfeeding practices were initially assessed using chi-square tests and then through multivariable logistic regression models. These analyses were performed first with any food insecurity (yes/no) and then with the category of food insecurity (none/marginal/moderate/severe) as the independent variable. Outcome variables were: (i) any breastfeeding for 6 months; (ii) exclusive breastfeeding post-discharge for 4 months and (iii) exclusive breastfeeding post-discharge for 6 months.

Two regression models were run with each breastfeeding outcome variable. Model 1 included the socio-demographic variables of post-secondary education (yes/no), parity (primiparous/multiparous) and CPNP site (5Ps/GST/HB). CPNP site was included to account for variations in client populations and service delivery between the three sites. Maternal age was not included due to limited variation across the sample. Model 2 included all Model 1 covariates as well as in-hospital formula supplementation (yes/no), which is a key determinant of breastfeeding practices reflecting perinatal care services. The same procedures described above were used to determine multicollinearity prior to modeling and to assess goodness-of-fit. Findings for all logistic regression analyses are reported using OR and 95 % CI.

In order to assess whether access to IBCLC services through the CPNP (yes/no) altered the association between household food insecurity and breastfeeding practices, we conducted a sensitivity analysis substituting this variable for CPNP site in the regression models. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis where all the original regression models were run using the complete dataset, without excluding any Study B participants based on changes in their food security status from prenatal to postnatal administration of the HFSSM.

Results

Study participants

A total of 337 participants were enrolled in the combined cohort out of a potential pool of 485 unique individuals (69 % recruitment rate), with 71 (15 %) declining to participate, 37 (8 %) ineligible and 40 (8 %) unable to be reached by the researchers (Fig. 1). Fourteen participants attended more than one CPNP site and enrolled in both studies simultaneously. The Study B record was retained for these participants, but their access to IBCLC through the Study A site was recorded. For a further three participants who enrolled in both studies but for separate pregnancies, only the record of the earlier pregnancy was retained. Retention was high, with 316 (94 %) completing the HFSSM at 6 months postpartum and included in the current analyses.

Fig. 1 Participant flow diagram

In this multi-ethnic cohort, the majority of participants in the combined studies were born outside Canada, including 38 % who arrived within the previous 3 years (Table 2). Two-thirds reported completion of post-secondary education, and half (49 %) were primiparous.

Prevalence and severity of household food insecurity

Household food insecurity was highly prevalent in this cohort, with 44 % of participants reporting any degree of food insecurity at 6 months postpartum (Table 2). Nearly one-quarter (23 %) were categorised as moderately food insecure and 11 % as severely food insecure. Prevalence of any household food insecurity varied by CPNP site, with 55 % at 5Ps, 38 % at HB and 19 % at GST.

Changes over time in household food security status

Data on both prenatal and postnatal household food insecurity were available for 137 participants in Study B. The designation of household food insecurity (yes/no) was consistent over time for the majority (78 %; n 107), with 56 % (n 77) classified as food secure and 22 % (n 30) classified as food insecure at both time points (Fig. 2). Of the remaining 22 % (n 30) reporting changes over time, 18 participants (13 %) improved to a postnatal food secure designation after being classified as food insecure prenatally. The remaining 12 participants (9 %) transitioned in the opposite direction, reporting household food insecurity postnatally but not prenatally.

Fig. 2 Changes in household food security status (Study B; n 137)

When severity of household food insecurity was considered, two-thirds of participants (65 %; n 89) were classified in the same category at both time points, 21 % improved and the remaining 13 % reported increased severity by one or more categories (Supplementary File 1). Stability of classification over time was most common among participants who were in either the food secure or severely food insecure categories.

Predictors of household food insecurity

Parity, maternal birth in Canada and CPNP site were identified in bivariate screening as potential predictors of any household food insecurity. In adjusted analysis, birth in Canada did not show a significant relationship with food insecurity, but multiparous participants were twice as likely to report any household food insecurity (OR 2·08; 95 % CI 1·28, 3·39) (Supplementary File 2). CPNP site was also found to be a significant predictor, with GST participants at lower risk of any household food insecurity than those registered at either the 5Ps or HB programmes (P < 0·001).

Associations between postpartum food insecurity and breastfeeding practices

All participants initiated breastfeeding and 80 % continued for 6 months, with 29 % and 16 % practising exclusive breastfeeding to 4 and 6 months postpartum, respectively, as previously reported(Reference Mildon, Francis and Stewart22). There was no association between any food insecurity and either continued breastfeeding for 6 months or exclusive breastfeeding post-discharge to 4 or 6 months postpartum in unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Table 3). In the fully adjusted model, CPNP site was the only statistically significant predictor of continued breastfeeding (P < 0·001), with GST participants less likely to breastfeed at 6 months than those from either 5Ps (OR 0·22; 95 % CI 0·10, 0·48) or HB (OR 0·40; 95 % CI 0·16, 0·97). Hospital formula supplementation was negatively associated with exclusive breastfeeding to both 4 and 6 months postpartum (OR 0·19; 95 % CI 0·10, 0·34 and OR 0·22; 95 % CI 0·11, 0·47, respectively). There was no significant association between the category of household food insecurity and any of the breastfeeding outcomes (Supplementary File 3).

Table 3 Associations between any food insecurity and breastfeeding outcomes (Ref: food secure)

Model 1 adjusted for maternal post-secondary education, parity and Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program site.

Model 2 includes all Model 1 covariates and hospital formula supplementation.

All analyses demonstrated goodness-of-fit based on the Hosmer Lemeshow test (P > 0·05). Model 2 analyses also met the desired threshold for AUC (> 0·7).

Consistent with these findings, there was no association between any household food insecurity or category of household food insecurity and any of the breastfeeding outcomes in multivariable logistic regression analysis of either the complete dataset or the sensitivity analysis substituting access to IBCLC through the CPNP for the CPNP site variable (Supplementary File 4).

Discussion

Household food insecurity affected almost half (44 %) of this cohort of women who registered at three Toronto sites of the CPNP, a national programme aiming to improve the nutrition and perinatal health of vulnerable women(12). Severe food insecurity was reported by 11 % of participants, indicating overt deprivation and the greatest risk of adverse health outcomes(Reference Perez-Escamilla, Vilar-Compte and Gaitan-Rossi26). The risk of household food insecurity varied between sites and was higher among multiparous participants. Household food insecurity was not associated with continued or exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months postpartum.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess household food insecurity among CPNP participants using the validated HFSSM, allowing for direct comparison with CCHS data. In this combined cohort, the prevalence of household food insecurity was nearly three times higher than the 2017–18 CCHS rate of 16·2 % among households with children(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell4). We expected to find a higher rate as the CPNP targets vulnerable families, and in a 2018 CPNP participant survey (n 3916), 31 % answered ‘yes’ to the single question assessing food insecurity (Have you ever not had enough to eat during your pregnancy?(27). When comparing data collected with the HFSSM, the magnitude of the difference between national data and our findings is striking and illustrates the disparities between sub-populations which can be masked in national figures. Similarly, a recent cross-sectional study that administered the HFSSM to women accessing prenatal care at two hospitals in the downtown core of Toronto (n 626) found an overall household food insecurity prevalence of 12·8 %, but a marked contrast between the sites, with a rate of 21·3 % among participants from the hospital serving a more socio-economically vulnerable population, compared with 4·4 % at the other site(Reference Shirreff, Zhang and DeSouza28).

The association between multiparity and household food insecurity in this cohort aligns with CCHS data showing a higher risk of food insecurity among households with children(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell4,Reference Tarasuk, Fafard St-Germain and Mitchell5) . This finding suggests a need for improved income support policies for vulnerable families, as well as for programmes such as the CPNP to consider household size and composition when allocating material supports. We did not find an association between maternal birth in Canada and household food insecurity, likely due to shared vulnerabilities among CPNP participants regardless of country of origin. Registration at the GST site was associated with a lower risk of household food insecurity compared with the other two sites despite similar socio-demographic characteristics for the available indicators. Additional data related to income and household structure are needed to explain the lower household food insecurity risk among GST participants. However, 19 % of GST participants reported household food insecurity, which is higher than national data despite being lower than the other two CPNP sites.

In this study, we did not find an association between household food insecurity and continued or exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months postpartum, contrary to our expectations. This is an encouraging finding and demonstrates participants’ commitment to breastfeeding despite living in conditions of hardship. It is possible that the lactation services available to the majority of participants had a mitigating effect not detected with the data available for the sensitivity analysis. It is also possible that social norms from participants’ countries of origin favour breastfeeding, consistent with the literature showing a greater likelihood of breastfeeding initiation and continuation past 24 weeks among immigrant mothers to high-income countries compared with their native-born counterparts(Reference Dennis, Shiri and Brown29).

Qualitative studies have identified critical challenges faced by food insecure families seeking to meet breastfeeding recommendations(Reference Frank17,Reference Gross, Mendelsohn and Arana18) , but prior quantitative evidence regarding the relationship between food insecurity and breastfeeding is limited. Analysis of CCHS data for 2005–2014 found that respondents reporting household food insecurity were no less likely to initiate breastfeeding but significantly less likely to exclusively breastfeed for 4 months(Reference Orr, Dachner and Frank11). In the United States’ National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (2009–2014), there was no relationship between food insecurity and breastfeeding initiation or overall duration among households with children 0–24 months of age(Reference Orozco, Echeverria and Armah30). Both of these studies were conducted with much larger, nationally representative, cross-sectional samples, and infant feeding data were collected retrospectively. In contrast, we recruited participants from the CPNP, a programme specifically targeting vulnerable families and providing some food supports. Thus, even the participants classified as food secure likely had more limited financial means than food secure women in the general population. In addition, Studies A and B were not primarily designed to test associations between household food insecurity and breastfeeding practices, so several potentially important covariates were not available for this posthoc analyses. These include household income, employment status, racial identity, lone parenting and maternal mental health status. In order to more accurately assess the relationship between food insecurity and breastfeeding, there is a need for studies with more complete data collection and larger, diverse samples, including representation from vulnerable women. Breastfeeding is often conceptualised as a mother’s individual choice, but household food insecurity, particularly when it is severe, maybe an under-recognised barrier in some sub-populations(Reference Frank17).

We found that household food insecurity status remained stable over time for most Study B participants, but there were reported transitions to and from household food insecurity. In addition to potential measurement error, these transitions may reflect instability in participants’ lives, many of whom were newcomers settling in Canada while adjusting to the arrival of a new baby. For 31 % of Study B participants, the 6-month postnatal HFSSM recall period included at least 2 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. This may have created additional instability for some participants, who anecdotally reported disruptions related to employment as well as travel bans, which reduced access to social support networks and resulted in a few participants being stranded in their home countries after returning to visit family, all of which could influence household food security status. Connection to services is another plausible unmeasured factor, with anecdotal comments from some participants indicating that their household food security situation improved as they became more connected to community supports or received an increase in government benefits with the birth of a child, while others transitioned from shelter accommodation where all meals were provided to living independently with social assistance funding, resulting in severe household food insecurity. Further research on the experiences of vulnerable families living close to the line between household food security and insecurity would guide efforts to strengthen supportive services and policies.

The multiple negative effects of household food insecurity on mental and physical health and child development are well established and known to escalate in a dose-response manner as the severity of food insecurity increases(Reference Perez-Escamilla6–Reference Tarasuk, Gundersen and Wang10,Reference Perez-Escamilla, Vilar-Compte and Gaitan-Rossi26) . Our findings therefore suggest the existence of significant health risks among CPNP participants at the sites engaged in this research, regardless of the lack of association with breastfeeding outcomes in our analysis. The CPNP serves women with a variety of vulnerabilities, not all of which entail economic hardship. There is a need to assess the prevalence and distribution of household food insecurity across the national programme and to consider the implications for programme design and service delivery. Assessment of household food insecurity is likely also warranted within similar programmes serving vulnerable families in other settings. These data would also allow examination of associations between household food insecurity and programme outcomes, including birth weight, breastfeeding, maternal mental health and other relevant outcomes. Such research has the potential to enhance efforts to improve perinatal health among vulnerable families.

A core CPNP service is the provision of food supports and/or grocery vouchers. A 2003 study found the contribution of CPNP supports to Toronto households reliant on social assistance to be so minimal that household food insecurity would not be impacted(Reference Vozoris and Tarasuk31). This finding remains relevant as funding allocations at the time of this research enabled CPNP sites to provide only CAD$10 in grocery vouchers to participants who attended the weekly programme. The weekly cost of a nutritious diet for a family of four in Toronto was calculated to be CAD$211·18 in 2019, a 29 % increase from 2009(32). Individual CPNP sites complement the CAD$10 benefit with other food supports as they are able, using charitable funds or food donations. The current CPNP intervention model may modestly increase access to nutritious foods but is not designed to reduce household food insecurity, which requires a stronger social policy response to insufficient household incomes(Reference Tarasuk1). A 2015 study in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia calculated that neither social assistance nor Employment Insurance maternity benefits based on prior minimum wage work would provide sufficient income for a nutritious diet for families with a 3-month-old infant whether exclusively breast- or formula-fed(Reference Frank, Waddington and Sim33).

Our findings also have implications for the provision of nutrition education through the CPNP and other programmes targeting vulnerable families. High rates of household food insecurity will not be impacted through education and will instead hinder participants’ ability to implement many nutrition recommendations. This requires consideration in the design of nutrition education curriculum. Continued emphasis on optimal nutrition practices in a context of household food insecurity may lead to feelings of guilt or anxiety among participants and may reinforce the perception that their breastmilk will be inadequate because of the poor quality of their own diets(Reference Frank17).

Strengths of this work include the high recruitment and retention rates in both Studies A and B, facilitated by the embeddedness of the lead researchers within the three CPNP programmes and the use of professional interpreters for non-English speaking participants. Household food security data were collected using the validated HFSSM, enabling comparison with other studies. We collected breastfeeding data prospectively to minimise recall bias and asked about all infant feeding practices to mitigate the risk of social desirability bias. However, data collection did not include all potentially relevant variables for the analysis of predictors of household food insecurity or associations with breastfeeding practices, and we were unable to assess the effects of household food insecurity on other perinatal outcomes. Our findings are not generalisable beyond the CPNP sites studied due to potential differences in participant characteristics and service delivery, including access to lactation support.

Conclusion

Nearly half of this cohort of women registered in the CPNP at three sites in Toronto reported household food insecurity at 6 months postpartum, with increased risk among multiparous participants. This is of public health concern given the multiple known adverse effects of food insecurity on mental and physical health of both adults and children. No association was found between household food insecurity and breastfeeding practices in this cohort. There is a need to assess the prevalence and severity of household food insecurity across all CPNP implementing sites and in other programmes serving vulnerable families in order to inform programme and policy responses.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of all study participants, and Yiqin Mao and Stephanie Zhang for their assistance with recruitment and data collection for Study B. Authorship: A.M. contributed to the design and conceptualisation of the work, led implementation and data collection for Study B, conducted primary data analysis for this work, drafted the manuscript and finalised it for submission. J.F. contributed to the design and conceptualisation of the work, led implementation and data collection for Study A and assisted with data analysis and interpretation for this work. S.S., B.U., YN and C.R. facilitated the integration of research activities into the community CPNP programs. V.T. contributed to the design and conceptualisation of the work, including the design of Study A and guided interpretation of findings for this work. E.D.R. contributed to the design and conceptualisation of the work, including the designs of both Study A and B. C.L.D. contributed to the design and conceptualisation of the work, including the design of Study B. D.L.O. and D.W.S. gave oversight to the design and conceptualisation of this work and to Studies A and B, and provided guidance for data collection, analysis and interpretation. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Office of Research Ethics of the University of Toronto. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Financial support:

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Doctoral Research Award (#GSD-157928) to AM and by The Sprott Foundation and the Joannah and Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition. The graduate student stipend of JF was supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship and Peterborough K.M. Hunter Charitable Foundation Graduate Award. The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Conflict of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980023000459