The start of sedentary farming and herding in the Middle East transformed social and economic organisation and reshaped ideological structures and artistic representations. Tepe Baluch is a Neolithic settlement on the Neyshabur Plain in north-east Iran. Amongst the ceramic material excavated at the site, one particular sherd is of great interest. It is decorated with two (possibly three) motifs in the form of human figures. For this date and region, such Neolithic iconography is rare, and this short article develops a comparative analysis to explore its significance.

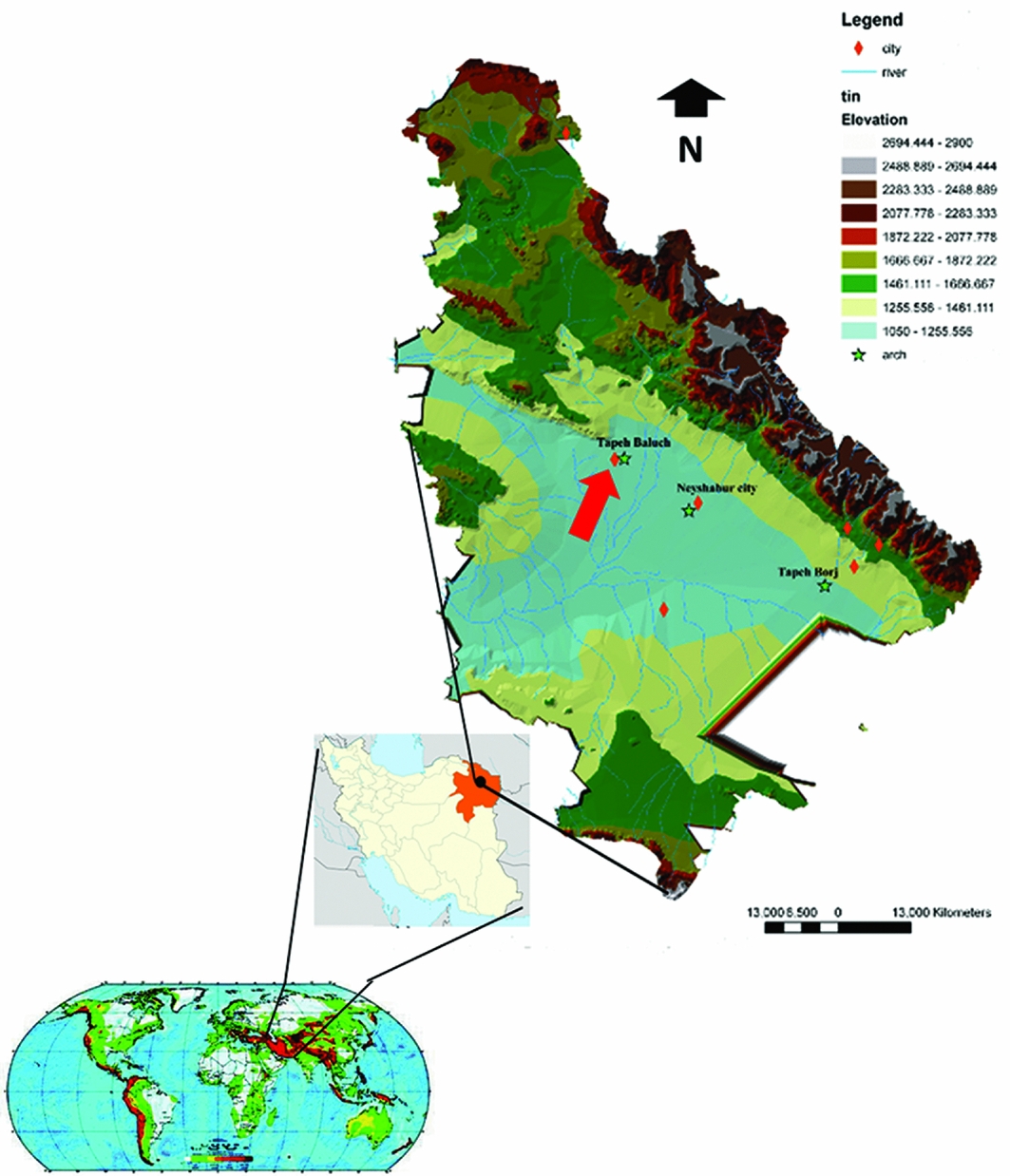

The site of Baluch is located on the outskirts of village of Taqi Abad, 17.5km west of the city of Nishapur in the province of Khorasan Razavi (E 58° 36′ 28′′, N 36° 18′ 35′′; Figure 1). Archaeological excavations were undertaken at the site in summer 2011, identifying Neolithic and Iron Age contexts (Garazhian Reference Garazhian2011; Figure 2). On the basis of the available natural resources, it seems probable that the site was occupied seasonally (Garazhian Reference Garazhian2013: 30).

Figure 1. Location of Tepe Baluch in north-east Iran.

Figure 2. View of excavations at Tepe Baluch (Garazhian Reference Garazhian2013: fig. 5).

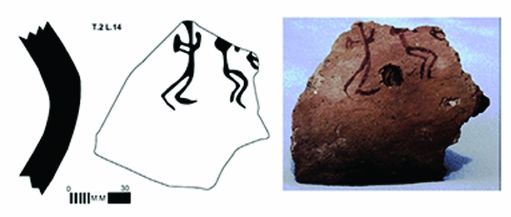

During the excavations, a sherd of pottery with human motifs was discovered in layer 14 of trench 2 (Figure 3). The sherd is 80mm in length, with an average thickness of 14mm, and is made of brownish buff paste with sand temper that seems inadequate for high-temperature uses. The sherd has a buff slip on both the internal and external surfaces, with painted dark-brown human motifs on the exterior. On comparative grounds, in terms of paste, the sherd should date to the Early Neolithic. This makes the presence of the human motifs unique in the region for this date (Garazhian Reference Garazhian2011, Reference Garazhian2013: 26).

Figure 3. Human motifs on pottery sherd from Tepe Baluch (Garazhian Reference Garazhian2013: fig. 18).

The human motifs are depicted in a partial side view. Two of them are complete; a probable third figure is broken off at the edge of the sherd. The motifs omit any detail of the face, head and body. No clothing is suggested and the sex of the figures is not apparent. The two preserved figures hold up their open hands, and the legs are bent at the knee indicating movement. The dynamism and broad symmetry of the figures, moving in opposite directions, may indicate dance.

A number of researchers have studied human motifs on prehistoric pottery (e.g. Dunn-Vaturi Reference Dunn-Vaturi2003; Gabbay Reference Gabbay2003; Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel2003a). Joseph Garfinkel (Reference Garfinkel2003b) has provided the most comprehensive account with a global survey of human motifs on prehistoric pottery, placing special emphasis on the Middle East. His comparative study has also developed a typology of motifs based on body form and the style of depiction. Figures 4 and 5 show how the Baluch motifs relate to Garfinkel's typology.

Figure 4. Diagram of human motifs and the position of the Baluch motifs within it (Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel2003a: fig. 8.8).

Figure 5. Table of human motif forms and the position of the Baluch motifs within it (Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel2003a: fig 2.3).

Stylistically—without regard to geographic and chronological contexts—the posture of the human motifs of Tepe Baluch can be compared to the figures in the hunting scenes from Çatalhöyük (Mellaart Reference Mellaart1963: pls XLV & LIV) (Figure 6a) and the human motifs of Tepe Gawra (Tobler Reference Tobler1950: pl. LXXVab) (Figure 6b), Sakje Gozu (Garstang et al. Reference Garstang, Phythian-Adams and Seton-Williams1937: pl. XXV-15) (Figure 6c) and Sabi Abyad (Akkerman Reference Akkerman1967: figs 21–40) (Figure 6d).

Figure 6. Human motifs comparable with the Baluch paintings.

The emergence of human motifs and the representation of movement (dancing?) is documented at many archaeological sites across the Middle East, especially Iran, in the fourth and fifth millennia BC (Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel2003a: 85). The preliminary date of the Tepe Baloch sherd with its human motifs is earlier: the seventh and eighth millennia BC.

The significance of the motifs may relate to ritual and ideological beliefs within this Early Neolithic society. The sherd was discovered in the context of a stone structure alongside the horns of a wild mammal (Garazhian Reference Garazhian2013: fig. 21; Figure 3). The Khorasan practise a type of local fast-paced dance, which is comparable to the Tepe Baluch motifs, yet the use of ethnographic parallels across extremely long time scales to interpret and explain these motifs in terms of body form and movement of the hands and feet is, however, problematic. Regardless, this sherd points to the social and ideological complexity of the early farming societies of Iran.

Acknowledgements

We thanks H. Talai, O. Garazhian and Y. Garfinkel for their help and guidance.