Introduction

Rare diseases number between 5000 and 8000.Footnote 1 Each affects fewer than 200,000 individuals,Footnote 2 but in the aggregate, they affect millions. As summarized in a National Academies Report, Rare Diseases and Orphan Products: Accelerating Research and Development:

Because the number of people affected with any particular rare disease is relatively small and the number of rare diseases is so large, a host of challenges complicates the development of safe and effective drugs, biologics, and medical devices to prevent, diagnose, treat, or cure these conditions. These challenges include difficulties in attracting public and private funding for research and development, recruiting sufficient numbers of research participants for clinical studies, appropriately using clinical research designs for small populations, and securing adequate expertise at the government agencies that review rare diseases research applications or authorize the marketing of products for rare conditions.Footnote 3

Information sharing, collaboration, and community building among researchers, doctors, and patients are critical to rare disease research. The Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) is an NIH program aimed at developing infrastructure and methodologies for rare disease clinical research by creating a network of research consortia. Each RDCRN consortium (RDCRC) involves researchers, other health care professionals, and patients at a group of geographically dispersed clinical sites.

Medical knowledge is a nonrivalrous resource, which can be used to treat any number of patients without diminishing its value to others. RDCRCs nonetheless face resource governance challenges, including (1) managing rivalrous inputs, such as research funding and researcher time; (2) managing rivalrous incentives and rewards, such as authorship credit; (3) overcoming incentives to hoard scarce access to patients and their data; (4) reducing the transaction costs of cooperation between widely dispersed researchers; and (5) managing interactions with outsiders, such as pharmaceutical companies.

All scientific research confronts tensions between the need to apportion scarce, rivalrous resources and the value of sharing nonrivalrous research results and certain infrastructural dataFootnote 4 and tools broadly. Mechanisms for managing this tension include public funding, reputation-based systems of peer review and publication, and scientific community norms. In clinical research, additional tensions between the value of the research and potential risks to research subjects are addressed by informed consent regulation, professional ethics prioritizing duty to patients, and institutional review boards (IRBs). These form part of the backdrop for the RDCRN and its associated consortia.

We previously studied the Urea Cycle Disorder Consortium (UCDC).Footnote 5 Here we focus on the North American Mitochondrial Disease Consortium (NAMDC). The next chapter in this book studies the Consortium for Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Research (CEGIR).Footnote 6 While there are many similarities between these consortia, which face common rare disease research problems and are structured by the RDCRN, there are also significant differences in the underlying challenges the groups face and the approaches they take to those challenges. The UCDC is much better established than the NAMDC and emerged from a history of greater previous cooperation. CEGIR is very new, but, like the UCDC, emerged from a close-knit group of researchers. Mitochondrial disorders are complex, varied, and difficult to diagnose, much less treat. The diseases studied by UCDC and CEGIR are comparatively well understood, with relatively well-accepted diagnostic criteria and targets for treatments. The consortia also have leaders with different styles and personalities and different governance structures.

15.1 Methodology

Our study follows the Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) framework described in Chapter 1. Specifically, we

Reviewed public documentation about NAMDC and were provided access to some internal documents, including minutes of consortium meetings and monthly reports.

Interviewed 22 individuals including NAMDC’s two consortium principal investigators (PIs), project manager, biostatistician, data manager, and budget administrator, site PIs from 9 of the 16 other clinical sites, a researcher consultant working with NAMDC on issues of diagnosis, NAMDC’s two assigned NIH officers, the executive director and scientific director of the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation patient advocacy group, one NAMDC study coordinator and one unassociated mitochondrial disease practitioner and researcher. The semi-structured interviews ranged in length from 45 minutes to more than an hour. We used the GKC framework to structure the interviews.Footnote 7

Attended NAMDC’s first half-day Face-to-Face Meeting, held in June 2015 in association with a conference sponsored by the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation (UMDF) patient advocacy group. We were silent observers throughout the meeting, although we introduced ourselves and our project and spoke with participants informally during the breaks.

Conducted an online survey designed to supplement our interviews, both by obtaining additional perspectives and by testing some of our observations. We emailed survey links to a list of potential respondents, including 24 active NAMDC researchers (the two consortium Co-PIs, 18 site PIs, a researcher consultant, a research fellow, the NAMDC biostatistician, and the director of the biorepository); NAMDC’s project manager and data manager, 2 NIH representatives, a Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC) representative, two UMDF representatives, and 13 study coordinators at 10 NAMDC sites. We received responses from 12 active researchers, representing 9 out of the 17 clinical sites,Footnote 8 and 7 others. Only one study coordinator completed the survey in full. Because the number of survey respondents was too small for meaningful statistical analysis, we treated the survey responses primarily as additional input to our qualitative analysis.

Analyzed the information we obtained using the GKC framework. With the exception of the study coordinators, we believe that our interviews and survey responses combined provide quite comprehensive coverage of NAMDC’s participants. We received at least some input to the study from virtually the entire leadership/administrative team at Columbia University, from PIs at 13 out of 17 clinical sites, from the single consultant researcher and from the NIH and UMDF representatives.

15.2 NAMDC’s Background Environment

NAMDC’s larger context includes the biological realities of mitochondrial disorders, the cultural contexts of medicine and academic research and the more specific contexts of rare disease research and the RDCRN.Footnote 9 We refer the interested reader to that case study for more detail.

15.2.1 The Basic Biology of Mitochondrial Disease

Mitochondrial disease medicine and research have developed mostly over the past 25 to 30 years. Mitochondria are responsible for creating more than 90 percent of the energy our bodies need to sustain life and growth. When mitochondria fail, cells are injured and can die, and if this process repeats itself through the body, various systems can fail and life can be compromised. While mitochondrial diseases mostly affect children, adult onset is increasingly common.

As the NAMDC website explains:

Mitochondrial diseases are a challenge because they are probably the most diverse human disorders at every level: clinical, biochemical, and genetic. Some are confined to the nervous system but most are multi-systemic, often affecting the brain, heart, liver, skeletal muscles, kidney and the endocrine and respiratory systems. Although severity varies, by and large these are progressive and often crippling disorders. They can cause paralysis, seizures, mental retardation, dementia, hearing loss, blindness, weakness and premature death.

Because of the range of symptoms and the frequent involvement of multiple body systems, mitochondrial diseases can be a great challenge to diagnose. Even when accurately diagnosed, they pose an even more formidable challenge to treat, as there are very few therapies and most are only partially effective.Footnote 10

Because mitochondria affect the functioning of virtually every bodily system, mitochondrial disease research is particularly important.

As one of our interviewees explained, because of the diversity and heterogeneity of mitochondrial disorders, “establishing a diagnosis often remains challenging, costly, and, at times, invasive”:

[For the urea cycle disorders] yes, there is a variable presentation, but … the spectrum is … defined. Whereas with mitochondrial disease, any system, any organ, anything. If you have no diagnosis at all, you could be possibly mitochondrial. There’s so much ambiguity in the physicians’ minds and the patients’ minds, and the general community’s minds about these diseases. I think it’s a very different kettle of fish.

Diagnosis may be controversial, as reflected in highly publicized incidents in which parents who believe their children are suffering from mitochondrial diseases have been accused of “medical child abuse” or Munchausen by proxy.Footnote 11

New rapid genomic sequencing technologies hold out hope of providing a “single test to accurately diagnose mtDNA disorders”Footnote 12 in patients who exhibit symptoms.Footnote 13 It is possible for a patient to have a genetic mutation without having a disorder, however, potentially leading to misdiagnosis.

15.2.2 The Mitochondrial Medicine Society and the Interplay between Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research

Mitochondrial disease presents two broad, overlapping categories of knowledge problems. First, physicians must decide how to treat their patients, given the difficulty in diagnosing mitochondrial disease and the lack of definitive treatments. Second, clinical researchers must develop generalizable knowledge that can be used to improve diagnosis and develop new treatments. The line between these categories is somewhat artificial, given that clinical research revolves around existing patients but is an important constraint on NAMDC’s goals and activities. As one NIH official explained: “NIH draws a line. NIH doesn’t train physicians to take care of patients. NIH trains physicians to do research with patients.”

The gold standard approach to treatment is to use robust clinical trial evidence to develop “clinical practice guidelines.”Footnote 14 When available evidence is insufficient to meet that standard (as is often the case for rare diseases), professional societies often develop multi-expert “consensus statements,” which are “derived from a systematic approach and a traditional literature review where randomized controlled trials and high-quality evidence do not commonly exist”Footnote 15 and “synthesize the latest information, often from current and ongoing medical research.”Footnote 16 Consensus statements aim to “help standardize the evaluation, diagnosis, and care of patients” until they can be “superseded by clinical trials or high-quality evidence that may develop over time.”Footnote 17

The Mitochondrial Medicine Society (MMS),Footnote 18 a practitioner organization, focuses on educating clinicians and developing materials to assist them with diagnosis and treatment. Citing “insufficient data on which to base [clinical practice guidelines],” “notable variability [] in the diagnostic approaches used, extent of testing sent, interpretation of test results, and evidence from which a diagnosis of mitochondrial disease is derived” and “inconsistencies in treatment and preventive care regimens,” MMS sponsored the process leading to a 2015 consensus statement for mitochondrial diseases.Footnote 19

Many NAMDC researchers also are heavily involved in the Mitochondrial Medicine Society. Indeed, 13 of the 2015 Consensus Statement’s 19 coauthors are NAMDC members. Moreover, all of the past presidents of MMS, along with its current president and two of its five other officers and board members, are NAMDC PIs. As one of our interviewees explained, “I’m the president of the Mitochondrial Medicine Society and I’m also a PI in NAMDC, I run a NAMDC site. I have been a trustee for the UMDF, and I am about to join the Scientific and Medical Advisory Board. I kind of have all three hats on at the same time.”

15.2.3 The Rare Disease Clinical Research Network

The RDCRN aims “to advance medical research on rare diseases by providing support for clinical studies and facilitating collaboration, study enrollment and data sharing.”Footnote 20 As explained in the 2008 request for consortium proposals:

Rare diseases pose unique challenges to identification and coordination of resources and expertise for small populations dispersed over wide geographic areas. Rare diseases research requires collaboration of scientists from multiple disciplines sharing research resources and patient populations. Rigorous characterization and longitudinal assessment is needed to facilitate discovery of biomarkers of disease risk, disease activity, and response to therapy. In addition, systematic assessment could resolve controversies concerning current treatment strategies. Well described patient populations will be important to bring promising therapies to the clinic.Footnote 21

RDCRCs are selected through a competitive peer-review process and must have the following components:

a minimum of two clinical research projects (at least one of them must be a longitudinal study)

a training (career development) component

at least one pilot/demonstration project

a website for educational and research resources in rare diseases

collaboration with patient support organization(s)

an administrative unit.Footnote 22

RDCRCs work closely with NIH scientists, through the “multiproject cooperative agreement (U54)” mechanism, in which a program coordinator from the Office of Rare Diseases and at least one NIH project scientist have “substantial scientific/programmatic involvement during the conduct of this activity through technical assistance, advice and coordination above and beyond normal program stewardship for grants.”Footnote 23

NIH also funds a centralized RDCRN Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC), which provides “coordinated clinical data integration of developed and publicly available data sets for data mining at RDCRCs, web-based recruitment and referral [of patient research participants], and a user-friendly resource site for the public” and manages the “collection, storage, and analysis of RDCRC data.” It also is tasked with “monitor[ing] [protocol] compliance while addressing privacy and confidentiality issues related to database management, distributed computing, and multi-level data sharing.”Footnote 24 The DMCC maintains the RDCRN Contact Registry, where patients can indicate interest in participating in clinical research or trials.

15.2.4 The United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation

NAMDC partners with the largest patient advocacy group focused on mitochondrial diseases, the UMDF, which was founded in 1996 by its current executive director. In 2013, it hired a full-time science/alliance officer with a PhD in chemistry. UMDF’s mission is “to promote research and education for the diagnosis, treatment, and cure of mitochondrial disorders and to provide support to affected individuals and families.” UMDF attacks it mission through patient support groups, funding research, educating patients and physicians about mitochondrial disease, and advocating public policies supporting mitochondrial disease patients and researchers. UMDF sponsors an annual national symposium that includes both a scientific component for basic researchers, clinical researchers, and clinicians and a component for patients and families, affording them opportunities to learn about the latest research, meet with mitochondrial disease specialists, and participate in Q&A sessions. UMDF also sponsors “grand rounds” about mitochondrial disease at various medical schools.Footnote 25

Compared to many other rare disease patient advocacy groups, UMDF is large, with a paid staff of 20 and a total budget of US$3.4 million. It has provided more than US$13 million in research grants, usually to pilot projects or beginning researchers. UMDF supports NAMDC’s project manager out of its research budget.

Recently, UMDF inaugurated a patient-populated Mitochondrial Disease Community Registry aimed at “collecting the patient voice: quality of life issues, opinions on various matters,” and “symptoms, extent of symptoms, what are the symptoms most important to you?” so as to “help drug developers whether they be in academia or in industry to understand the patient better, as opposed to just their medical condition.”

UMDF was described by interviewees as a “hub of activity” related to mitochondrial disease or the “glue” holding different components of the effort together. An interviewee told us that UMDF is known for doing a good job of “getting on the radar screen of NIH.” UMDF’s science/alliance officer described his job as “connecting dots” with “UMDF in the center of this very complex process called therapeutic development, that has all kinds of bubbles around it. It’s the patient community, it’s the research community, it’s the pharmaceutical community, it’s the government, government agencies, clinical research network like NAMDC … all of these things overlap with UMDF in the middle, serving as a clearinghouse.”

Most of NAMDC͛s researchers have long-standing relationships with UMDF that precede NAMDC’s formation. Consortium PI Salvatore DiMauro, for example, was involved with UMDF from its inception. Currently, seven NAMDC members are on UMDF’s Board of Trustees or Scientific Advisory Board. NAMDC researchers also have been involved in planning and participating in the UMDF annual symposia and grand rounds. NAMDC schedules its annual face-to-face meeting of its researchers to coincide with the UMDF symposium, which many or most of them attend regularly.

15.3 The NAMDC Consortium

NAMDC is shaped by its own particular goals and history, by the individuals who make up the community, and by its governance structure, which are described in this section.

15.3.1 Goals and Objectives

NAMDC’s makeup, the resources it creates and employs, and its governance structure center on its goals and objectives, which also provide metrics for assessing its success. NAMDC shares many of its overarching goals with other RDCRN consortia, though its specific objectives are tailored to the mitochondrial disease context. As NAMDC’s mission statement explains:

The challenge for the NAMDC is the extraordinary clinical spectrum of mitochondrial diseases, which all too often leads practitioners to either underdiagnose (“What is this complex disorder?”) or overdiagnose (”This disorder is so complex that is must be mitochondrial!”). Yet mitochondrial diseases cause similar metabolic defects and presumably share – albeit to different extents – the same mechanisms. Thus, the availability of a mitochondrial patient registry and of a consortium will have a powerful impact in multiple ways, as already documented by similar organizations operating in Europe.Footnote 26

In light of this mission, NAMDC articulates the following objectives:

First, NAMDC will make these rare and still unfamiliar diseases known to practitioners and to the general public.

Second, it will facilitate correct diagnosis by making “centers of excellence” available to physicians and affected families alike.

Third, it will offer affected families the comfort and advice of a patient support group, the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation (UMDF).

Fourth, it will foster clinical research, such as natural history, that would be otherwise impossible because it requires relatively large cohorts of patients.

Fifth, it will also foster more basic research by revealing unusual patients, leading to the discovery of new genetic defects.

Finally, NAMDC will conduct rigorous and innovative therapeutic clinical trials.Footnote 27

NAMDC approaches these goals and objectives through specific activities:

Create a network of all clinicians and clinical investigators in North America (US and Canada, with the hope of including Mexico in the future) who follow sizeable numbers of patients with mitochondrial diseases and are involved or interested in mitochondrial research.

Create[] a clinical registry for patients, in the hopes of

standardizing diagnostic criteria,

collecting important standardized information on patients,

facilitating the participation of patients in research on mitochondrial diseases.

Establish[] a repository for specimens and DNA from patients with mitochondrial diseases, in order to make materials easily available to consortium researchers.

Conduct clinical trials and other kinds of research. The consortium makes biostatisticians, data management experts, and specialists in clinical research available to participating physicians, so that experiments conducted through the NAMDC can make the most efficient and innovative use of the generous participation of patients.

15.3.2 NAMDC’s History

When the RDCRN program began in 2003, NAMDC’s consortium PIs, Salvatore DiMauro and Michio Hirano of Columbia University, proposed a mitochondrial disease consortium, to be called MAGIC. According to one of our interviewees: “The group in Columbia is a very well established and reputable group in the US, for the study of mitochondrial disorders. At some point it was the only one. It was the first one. It was good that very traditional and well-established leaders in the field started with the concept of having NAMDC and bringing people together.” Several interviewees also emphasized the UMDF’s important role as a catalyst for that initial proposal.

MAGIC was not funded in either of the RDCRN’s first funding rounds. PI Hirano attributes the early funding failures primarily to the relative immaturity of the field and the consortium PIs’ lack of clinical research expertise. In 2010, NAMDC received partial funding for two years through an American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) grant,Footnote 28 which focused on setting up basic infrastructure for the consortium:

This application aims at establishing the infrastructure needed to launch a mitochondrial disease patient registry, biorepository, and a North American Mitochondrial Disease Consortium (NAMDC) with the support of [patient advocacy group] UMDF. The NAMDC will feature advanced data management systems and statistical design capabilities provided by the Statistical Analysis Center (SAC) in the Department of Biostatistics at Columbia University. This structure will be the indispensable basis for future collaborative studies of epidemiology, natural history, therapeutic trials, as well as in-depth research on pathogenesis.Footnote 29

In 2011, NAMDC transitioned to a standard RDCRN grant, which was renewed during the RDCRN’s 2014 funding cycle.

During the ARRA grant period, NAMDC’s PIs decided to work closely with biostatistician John (Seamus) Thompson at Columbia’s Statistical Analysis Center (SAC), which still provides primary data services for NAMDC:

The [ARRA] money was absolutely necessary because it allowed us to work with Seamus Thompson and his statistical analysis center. We had never worked together before. They had all the database capacity and clinical trial expertise … I was mainly, you know, a lab person at the time. I had not done this kind of clinical research. I needed their complementary expertise and tools. This allowed us to do it. This grant really funded us and put us together.

This is obviously greater than the sum of its parts because Seamus had the expertise in statistics and database management and [] clinical trials and all of the things that we lacked, and we had the clinical expertise … Billy DiMauro and I sat down and we created all of the … information that we wanted. And Seamus was then able to turn that over to [data manager] Richard Buchsbaum who was then able to put it all into a data management system.

The choice to work with Thompson and Columbia’s SAC appears to have had several important consequences for NAMDC’s institutional development. NAMDC has a relatively loose relationship with the RDCRN’s Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC), as compared to other RDCRCs. Though NAMDC provides copies of its data to the DMCC, data from NAMDC sites is collected, stored, and handled primarily through Columbia’s SAC.Footnote 30 NAMDC’s Project Manager Johnston Grier and Data Manager Richard Buchsbaum both came to NAMDC from the SAC. Finally, as we will discuss later, NAMDC’s site funding model was grounded in Thompson’s experience with clinical trials.

15.3.3 NAMDC’s Participants

15.3.3.1 Columbia-Based Leadership Team

Consortium PIs DiMauro and Hirano are well-established mitochondrial disease clinicians and researchers, with large numbers of publications and a history of NIH grant support. DiMauro was described by another researcher as “the leading light founding father of modern mitochondrial disease.” Hirano currently provides most of NAMDC’s day-to-day leadership, spending about 40 percent to 50 percent of his time on consortium activities. Hirano has been working in the field of mitochondrial diseases since 1990, having received his MD at Columbia and completed a residency and a fellowship with DiMauro. He describes the subject as his “passion.” Like all NAMDC researchers, Hirano divides his time between treating patients and research. Prior to setting up NAMDC, he was a laboratory researcher, without clinical research experience.

Biostatistician Thompson’s educational background is in sociology, but his time is now devoted entirely to providing biostatistics expertise and services to clinical researchers. He spends about 20 percent to 25 percent of his time on NAMDC.

Project Manager Grier is an integral part of the leadership team at Columbia and plays the central part in interfacing between the Columbia team and other clinical sites on virtually all nonscientific issues, such as organizing meetings and conference calls, overseeing the IRB process, and training site coordinators to enter data into NAMDC’s database. He also had primary administrative responsibility for NAMDC’s 2014 renewal proposal.

Data Manager Buchsbaum acts as “an interface between researchers, mostly clinicians, but researchers of all kinds, and the people who deal with the data” for NAMDC and many other Columbia projects. He provides

a back-end IT infrastructure for research as an enterprise. Which means … designing systems to collect or integrate research data, but it also means everything from scheduling to billing to other things where data systems can be of use. I program them, I supervise other programmers who program them, I do what might be equivalent to management consulting in terms of people will come with a protocol and I say, well, yes, but what happens when the patients don’t behave the way you expect them to?

He “like[s] to be involved in the later stages of protocol development because [his] point of view is primarily a logistical one, which is not often represented in designing [protocols].”

The Columbia team also includes a site study coordinator and administrators who deal with budget and finance issues and spend only a fraction of their time on NAMDC work.

15.3.3.2 Other NAMDC Researchers

NAMDC’s membership includes 18 active principal investigators (site PIs) associated with the 16 other clinical sites, as well as a researcher consultant unaffiliated with a clinical site, whose work has focused on the diagnosis action arena described later in Section 15.4.2.1. All site PIs are specialists in treating patients with mitochondrial disease and have medical degrees. About half also have PhDs. Their backgrounds are primarily in genetics, pediatrics, and neurology. Most were engaged in mitochondrial disease research before their association with NAMDC. NAMDC’s PIs are extremely busy and hardworking people, who see patients; do research; and, in many cases, shoulder significant administrative responsibilities at their institutions. The effort that they are able to devote to research varies widely, depending largely on their clinical responsibilities, with some devoting about 80 percent of their time to research and others struggling to free up 20 percent of their time for research. All site PIs are responsible for enrolling patients in the NAMDC Patient Registry and Biorepository, which is NAMDC’s version of the requisite longitudinal study. Some also conduct other NAMDC-sponsored studies.

15.3.3.3 Study Coordinators

Study coordinators perform many of the nitty-gritty tasks of clinical research, such as entering data into the NAMDC databases correctly, completely, and in accordance with protocols; obtaining informed consent from patients and ensuring IRB compliance at their study sites; and handling general administrative duties. They also often have major responsibilities for patient contact, arranging appointments, and so forth. Study coordinators have a variety of backgrounds. In the United States, they often are geneticists or nurses. Some, especially outside of the United States, have MD or PhD degrees. About half of NAMDC’s clinical sites have at least one regularly affiliated study coordinator. At other sites, study coordinator duties are either assigned on a task-by-task basis or are performed by the site PI.

15.3.3.4 NIH and UMDF Representatives

NAMDC interacts closely with two NIH officials, a program officer and a scientific officer, as required by the U54 grant mechanism. The scientific officer is effectively “embedded” in the research community, participating in monthly telephone calls, helping develop research protocols, and even assisting with grant proposals. The program officer’s role focuses mostly on administrative oversight, though it also involves assisting the consortium with its interactions with the NIH. These NIH representatives work with multiple consortia and are sources of broad-based expertise in dealing with issues that commonly arise. One interviewee noted that they “have a really wide view of what’s happening in other consortia” and are able to contribute “very positively” based on that experience.

The UMDF’s executive director and science/alliance officer are active NAMDC participants, with the executive director serving on NAMDC’s executive committee.

15.3.4 NAMDC Governance

Our study identified three NAMDC governance institutions: (1) consortium-wide meetings, including monthly conference calls and an annual face-to-face meeting; (2) a committee structure; and (3) the Columbia leadership team.

15.3.4.1 Consortium-wide Meetings

NAMDC holds monthly conference calls and annual face-to-face meetings. Early conference call minutes reflect considerable discussion of NAMDC’s evolving policies and activities. Perhaps because many decision-making functions have been assigned to the committees described in the next section, interviewees described current conference calls as “more of update calls than … decision-making calls” and as “somewhat repetitive but necessary.” Large majorities of survey respondents agreed that conference call participation “contributes to my research” and disagreed that participation “takes too much time from my other responsibilities.”

In 2015, at the recommendation of its NIH representatives, NAMDC held its first half-day face-to-face meeting, in conjunction with UMDF’s annual conference, expanding an earlier practice of holding very short get-togethers at the event. Attendees included the Columbia leadership team, site PIs, several NIH representatives, two UMDF representatives, and the NAMDC fellow. Few study coordinators attended. The meeting covered many topics including the diagnostic criteria, issues with data entry and collection of biospecimens, data access policy, and selection of pilot studies. Several interviewees told us that the extended face-to-face discussion was valuable. As one put it, “I think most of the monthly meetings are pretty perfunctory. It makes me feel part of the community and you get updated. But I don’t think there’s a whole lot of time for discussion. [But the longer face-to-face meeting] was actually really good because I think it’s healthy to get together and see people and really just focus on the details. So that was a really valuable kind of unique experience, relative to the [] monthly phone calls.” Another interviewee commented that “of all the things, [the half-day face-to-face meeting] was the most productive, of all the sessions I’ve attended.”

15.3.4.2 Committee Structure

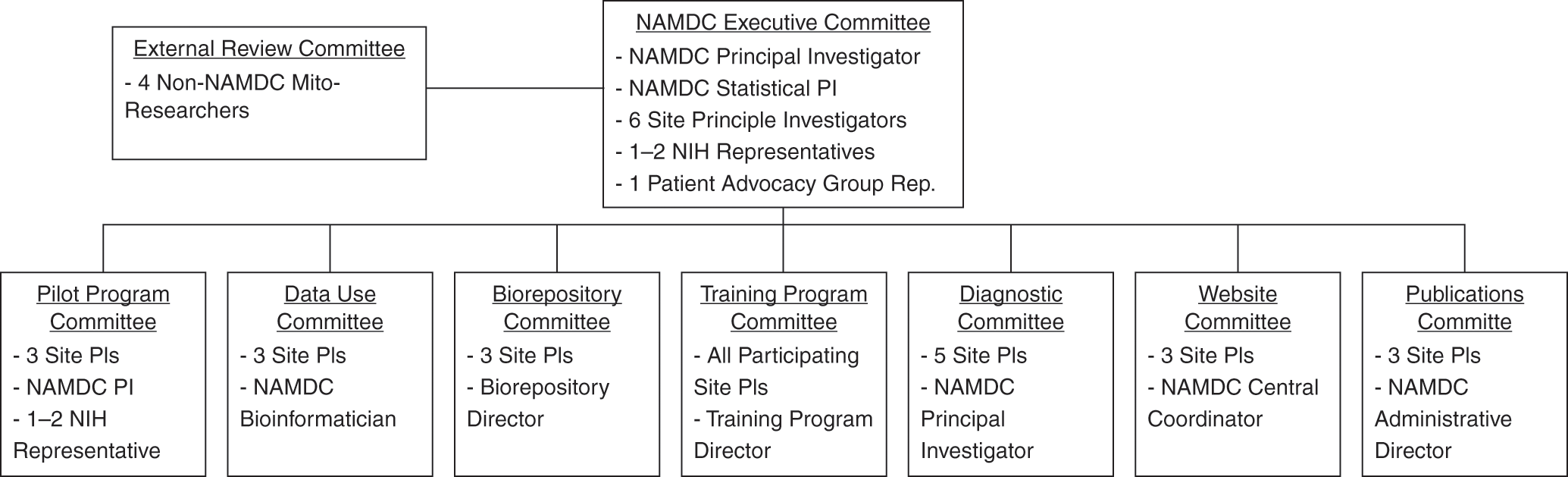

NAMDC’s committee structure, depicted in Figure 15.1, was established in 2014: “The overall goal of establishing NAMDC Committees is to distribute the workload of running the consortium and ensuring that everyone is participating actively.” On the whole, NAMDC’s committee structure was viewed positively by study participants. For example, strong majorities of survey respondents agreed that it “improves cooperative among researchers,” “improves NAMDC decision making,” and “makes NAMDC decision making less hierarchical,” and disagreed that it “adds unnecessary bureaucracy.”

Figure 15.1 NAMDC Committee structure.

The Executive Committee “is responsible for supervising the progress of NAMDC programs … setting the long-term strategic goals for the Consortium, and defining the terms and rules by which the Consortium interacts with outside entities … review[ing] all proposed NAMDC protocols … [and] review[ing] and either approv[ing] or deny[ing] the addition of future NAMDC Clinical sites.”Footnote 31 Prior to January 2014, the Executive Committee had been composed of every NAMDC site PI. The number of site PI members was reduced to six in 2014 because “with 18 different sites, some with multiple site PIs, this structure has been unwieldy.” Our interviews suggested that the balance of decision-making authority between the Columbia team and the Executive Committee structure was still a work in process. While interviewees who served on the Executive Committee reported active participation in decisions such as “voting in and out new clinics,” deciding whether NAMDC should publicly support activities of other organizations, final approval of pilot project funding, setting general research priorities for the consortium, and setting procedures for outsider access to NAMDC data, some interviewees were skeptical or unclear about the extent to which the Executive Committee really differed from the Columbia leadership group. One interviewee expressed the view that the Executive Committee “really is just leadership,” while another was of the opinion that the “Executive Committee has so far only been a committee in name. They haven’t really done anything. It really has been Michio as being the lead PI.” Some interviewees also reported a desire for more “transparency” in NAMDC decision making, particularly as to allocation of funds.

The Diagnostic Committee has been dealing with one of NAMDC’s greatest challenges: the establishment of research diagnostic criteria “to categorize patient’s mitochondrial disease diagnosis … for research purposes and to provide feedback to NADC site investigators about the evaluations and diagnoses of each patient enrolled in the NAMDC Clinical Registry.” The Diagnostic Committee is expected to “reevaluate and, if necessary, revise the NAMDC research Diagnostic Criteria on an annual basis.” The development of NAMDC Diagnostic Criteria is an important action arena discussed in Section 15.4.2.1.

The Pilot Program and Training Program Committees are responsible for activities familiar to most academics: reviewing grant proposals and selecting and supervising fellows. The Pilot Program Committee makes recommendations to the Executive Committee, which finalizes funding decisions, though finalists present their proposals at the face-to-face meeting, suggesting that broader input from site PIs also is taken into account. The Training Program Committee reviews applicants for NAMDC’s fellowship and runs the “curriculum” for the program.

The Data Use and Biorepository Committee is tasked with reviewing requests to use NAMDC data and specimens. NAMDC has formal data-use policies and procedures, but the committee appeared to be relatively inactive at the time of our study, perhaps because NAMDC’s data and specimen collections were at a relatively early stage. For similar reasons, NAMDC had not yet established a publication policy. The Website Committee, tasked with maintaining NAMDC’s public-facing website, also was not yet active. An interviewee explained that the website is administered by the RDCRN, so that changes would require NAMDC to “wait a long time and make the request to the RDCRN.” The relatively low priority apparently afforded to the public website is consistent with our UCDC observations. Perhaps this is because, beyond specific information about RDCRN studies, much of the information about rare diseases that would be of general public interest is available through patient advocacy group websites, for which public education is a priority.

15.3.4.3 Leadership

Leading an RDCRC is challenging. Consortium PIs are ultimately responsible for ensuring the success of the enterprise, but success depends on establishing norms of collaboration and cooperation. In an echo of our UCDC survey, survey respondents overwhelmingly selected “dedicated,” followed by “trustworthy” and “determined” as among the best descriptors of current NAMDC leadership.Footnote 32 Interviewees also described NAMDC’s leadership as “dynamic” and passionate. Interviewees consistently praised PI Hirano’s success in bringing researchers together and forging cooperative relationships, “winning the confidence of the group and bringing them together in these enterprises,” and instituting a “different model” from earlier times in which “there was a head guy, and he led the charge and that’s how science was done.” Interviewees described Hirano’s leadership style as “very collaborative in drawing people in,” “winning the confidence of the group and bringing them together,” “not … top-down,” “hav[ing] a very light touch and … working with [people] in any way he can,” “consensus building,” “reassuring … and not confrontational.” Several noted that they viewed these leadership traits as key to NAMDC’s success, particularly given the challenges of forming a consortium in mitochondrial disease research when there was not much prior history of collaboration between researchers at different institutions.

While most survey respondents who expressed a view agreed that NAMDC’s decision-making process is “fair” and “transparent,” several interviewees were concerned that both authority and responsibility were concentrated too heavily in the Columbia group. One described NAMDC as “rather centralized,” suggesting that it could be “a little more open in terms of soliciting suggestions and listening to the suggestions of others.” Another suggested that perhaps “Columbia itself, just as a business institution, [is] used to having PIs make decisions,” while a third was concerned that “site PIs may not necessarily feel like we have ownership … that we’re on the bus, but we’re not helping drive it.” Some believed that there should be more delegation of responsibility from consortium leadership, with one offering the following thoughts:

I suspect, as the lead PIs, they always feel like all the burden’s falling on them. They may not realize it’s because they may not have given the other PIs authority. We don’t feel like we have authority to take things on … I suspect that’s where things may fall apart, just because … it’s too much of a burden for one or two individuals in the group to carry it. After a while the rest may end up getting disengaged, and then things move down the wrong path.

In apparent tension with these comments, some interviewees expressed concern that NAMDC’s leaders were not sufficiently “directive” or demanding of consortium members, when “hold[ing] people’s feet to the fire … may be necessary.” One discussed the need for “setting goals, setting priorities, making this work, while capturing the creativity of the individual people,” suggesting that in some other consortia “it’s much more clear cut what they’re working on, how they’re moving forward, there is much more structure, and a personality to drive them to work together.”

These somewhat opposing views of NAMDC leadership were also mirrored in our survey results. Strong majorities of survey respondents who expressed a view agreed or strongly agreed with the statements “NAMDC decisions are based on consensus” and “NAMDC decisions are made by majority vote,” but strong majorities also agreed or strongly agreed that “Most NAMDC decisions are made by the leadership,” “NAMDC is hierarchical,” and “Site researchers should have more say in NAMDC decisions.” Often, the same individuals expressed both sorts of views.

We observed a similar tension between perceptions of (and desire for) both shared, consensus-based governance and strong leadership in the UCDC study, despite important differences between the two consortia. For example, the UCDC is much better established, emerged from a closer-knit community, deals with a less complex set of disorders, and appears to rely much less on a formal committee structure.

15.4 NAMDC’s Primary Action Arenas

An action arena is “the social space where participants with diverse preferences interact, exchange goods and services, solve problems, dominate one another, or fight (among the many things that individuals do in action arenas).”Footnote 33 Each action arena involves a particular set of actors; employs, produces, and/or maintains a set of resources; and, in most cases, confronts a set of challenges or dilemmas. Overcoming these challenges or dilemmas generally requires some form of informal or formal governance. Meeting NAMDC’s objectives requires cooperative efforts among NAMDC members, who may differ as to how best to accomplish those objectives, how to apportion responsibility and credit, and so forth. Moreover, constraints on funding, time, and attention mean that NAMDC must prioritize and make trade-offs between efforts addressed to the various objectives.

In this section, we discuss eight primary NAMDC action arenas observed in our study, identifying the actors and resources involved, and discussing the challenges or dilemmas that must be overcome. These action arenas can be grouped loosely into three categories: (1) creating and sustaining a collaborative research community; (2) developing and managing a shared pool of research subjects, patient data, and biological specimens; and (3) managing relationships with preexisting mitochondrial disease organizations. We do not discuss NAMDC’s interactions with pharmaceutical companies related to its objective to conduct rigorous and innovative therapeutic clinical trials. While this action arena is important, we found it too preliminary to delve into at this stage.

15.4.1 Creating and Sustaining a Collaborative Research Community

A research consortium’s success may depend significantly on the extent to which members form community relationships of mutual trust and responsibility. Nearly all NAMDC researchers responding to our survey listed “participating in a research community” as very important or essential to their decisions to join NAMDC and agreed that “NAMDC is a close-knit community.” One interviewee explained, “I really think that [there] is something beyond the practical aspects of it. There is something that improves your efficiency when you are part of a group.” We discuss three community building action arenas: (1) determining NAMDC’s membership, (2) promoting knowledge sharing and collaboration, and (3) recruiting and training mitochondrial disease clinical researchers.

15.4.1.1 Determining NAMDC’s Membership

To create a network of mitochondrial disease clinical researchers, NAMDC must motivate researchers to join; their expected benefits must outweigh their anticipated costs. While participation costs begin to accrue immediately, many benefits are only potential so far. Costs include time and money invested in obtaining IRB approvals and consenting patients for NAMDC studies; data entry; preparing samples for submission to the biorepository; and participating in NAMDC meetings, conference calls, and committees. NAMDC participation also has significant opportunity costs for busy clinician researchers. NAMDC continues to receive requests to join, suggesting that many researchers anticipate substantial benefits such as, most importantly, the possibility of improving patient treatment, as well as opportunities for challenging and interesting research and a competitive edge with respect to publications and professional status. More immediately, membership may foster productive and enjoyable collaboration and knowledge sharing.

Like any knowledge commons, NAMDC must balance inclusiveness against difficulties that accompany growth, some – such as limited resources, growing transaction costs, and difficulties in building community and avoiding shirking and free riding in a larger group – related directly to size, and others related to potential members’ compatibility with the group’s goals in terms of expertise, dedication, or other factors. Whether NAMDC can (or should) include “all” mitochondrial disease clinical researchers depends on the costs and benefits of growth.

One can conceptualize NAMDC’s “members” either as clinical research sites or as individuals. With the exception of the NIH and UMDF representatives and a few others, each individual member is affiliated with a NAMDC clinical research site. Expansion decisions are made on a site-by-site basis. We thus begin by considering the issues NAMDC confronts in determining which, and how many, clinical sites should be included and then briefly discussing some issues relating to members as individuals.

15.4.1.1.1 Selecting Clinical Sites

NAMDC began with 9 clinical centers. By June 2014, it had expanded to its current 17 sites. Adding clinical sites allows NAMDC to reach more patients and increase its pool of research subjects, data, and specimens, but it puts more strain on limited resources. Setting up and maintaining a site involve significant overhead, including the costs of obtaining IRB approval and of training clinicians and study coordinators to follow NAMDC protocols, as well as ongoing management and participation costs. When sites are added, current members benefit from increased collaboration and knowledge sharing and from the availability of a larger pool of data and specimens, but funding, and eventual publication and reputational credit, may be spread more thinly, while group decision making and interaction become more time consuming and complex.

NAMDC members are aware of these trade-offs. Nearly all survey respondents were moderately or very concerned that funding would be stretched too thin if more sites were added, while more than half were similarly concerned about increased bureaucracy and difficulty in making decisions. As one interviewee explained:

We’re very scattered. We already have, I think, 18 centers, and sure there are other people who are seeing patients that have mitochondrial problems, but the question is should we have 18 centers for a rare disease? The downside of having fewer centers is the lack of convenience for families and patients … The downside from the rare disease research side of things is that … if you’re not part of NAMDC, those patients aren’t necessarily getting enrolled into the database, their data is not coming to us … I think from the selfish side of things, I would opt for fewer centers … There would be more money to go around to those centers and allow for better development of those centers as opposed to many different centers getting a tiny amount of funding and just scraping by.

Another interviewee noted: “It’s already hard to manage the people that are present … [If you expand the consortium] how do you have a face to face … how do you even do monthly phone calls?” Indeed, some interviewees already often missed monthly conference calls because of scheduling conflicts.

NAMDC describes its target membership as those “who follow sizeable numbers of patients with mitochondrial diseases and are involved or interested in mitochondrial research.” This suggests four distinct aspects of inclusiveness, two of which – geographical coverage and patient numbers – focus on patients, while the other two – clinical expertise and research interest and experience – focus on researchers.

Broad geographical coverage makes it easier for patients to access a site. Focusing on patient numbers favors locating NAMDC sites at clinics that see the largest numbers of patients, which may be of no help to isolated patients but would reduce overhead costs.

Sites could also be selected based on clinical expertise. Given the difficulty of diagnosing and treating mitochondrial diseases, clinical expertise may be important to identifying, enrolling, and following patients over time. Sites with research interest and experience may be more efficient and may have access to experienced study coordinators and other clinical research professionals.

NAMDC explicitly takes patient numbers into account by requiring each site to enroll at least 15 patients during its first three years. At least two sites have been dropped because they failed to meet that requirement after a start-up period. As of October 1, 2015, two continuing sites had not met the requirement, however, suggesting that the enrollment requirement is not dispositive.

Geographical coverage appears to have played a more secondary role. NAMDC’s sites are concentrated roughly in the Northeast and on the West Coast, with additional sites in Florida, Texas, Colorado, and Minnesota.Footnote 34 This geographic distribution is probably a collateral consequence of focusing on researcher expertise and patient numbers, given that major academic medical institutions and population centers are similarly distributed. Nonetheless, NIH “wants the sites to be geographically diverse.” NAMDC’s most recently added site, in Denver, filled a coverage gap in the center of the country. Except for Cleveland, where the inclusion of two sites was “questioned by NIH,” NAMDC has only one clinical site per city and recently declined a request to add a second site in Houston.

NAMDC has attempted “from the outset [] to incorporate all of the, or most of the, mitochondrial disease experts in this country.” While opinions differed, our study participants mostly agreed that NAMDC is reasonably inclusive of active mitochondrial disease clinical researchers. According to interviewees, NAMDC has “captured most of the people who are seeing most of the patients” and “has been quite effective at getting most of them in,” and active clinical researchers outside of NAMDC are “increasingly few.”

Still, “there are many doctors who are clinically seeing patients, involved in clinical research, that are not NAMDC sites.” The Mitochondrial Medicine Society’s webpage displays a map of mitochondrial medicine specialists globally; several are in the United States, at academic medical centers, and not in close proximity to an existing NAMDC site. NAMDC must decide whether, how quickly, and where it should expand in light of the trade-offs involved.

NAMDC also must create a process for making those decisions. Its consortium PIs selected the sites included in the original NIH proposals. Subject to RDCRN approval,Footnote 35 based on general considerations including a proposed site’s commitment and the DMCC’s workload, NAMDC exercises considerable discretion about site expansion. Formally, NAMDC’s Executive Committee is now empowered to make decisions about adding and, when necessary, removing sites, but NAMDC leadership was considering whether to “make this a little more democratic and make sure that everyone has a vote and has a say in who’s in and who’s out.”

15.4.1.1.2 NAMDC as a Community of Individuals

Adding sites means integrating newcomers into the NAMDC community. Community building among NAMDC’s clinician-researchers is facilitated by the fact that they already belong to a relatively small community of practiceFootnote 36 and have a shared dedication to improving patient health. As one interviewee pointed out, “there aren’t that many people that have a focused desire and expertise to work in mitochondrial disease,” and many know one another through their training and other prior interactions. The mitochondrial disease research community overall was described as “a really congenial group, a really lovely group of people” and “very collegial,” and its members as “very committed” and “driven.” Nonetheless, when a relationship-based community grows, some strain on informal norms and trust relationships is likely.

Community building also means deciding how individuals at each site are incorporated into the NAMDC, which functions primarily as a community of site PIs. One PI observed that NAMDC has been a “pretty PI-driven group” and not “overly open to support staff.” Though study coordinators and other support personnel at some NAMDC sites see themselves as “very active participants” in NAMDC’s work, their interactions with the broader NAMDC community are PI-mediated “NAMDC communicates mainly through the PIs, perhaps the web list, the email invites go out to other people. But, like, at the face-to-face meeting, that was really just PIs who were welcome. I think you could take one research coordinator with you if you wanted to.” As a study coordinator interviewee explained, “I have nothing in my job description that makes me need to contact anybody else.”

This PI-mediated community model contrasts with that of the UCDC. UCDC study coordinators regularly attend consortium-wide meetings and have study coordinator telephone conferences. Study coordinator response rates to our survey may reflect this difference in community model. While 17 out of 25 UCDC study coordinators, representing 14 out of 15 sites, responded to our UCDC survey, only one NAMDC study coordinator responded.

Each model has advantages and disadvantages. Greater study coordinator cross-site interaction and direct involvement add both financial and transactional costs. UCDC employs consortium resources to fund dedicated study coordinator efforts at each clinical site and to finance study coordinator meetings. NAMDC does not “support anybody funding-wise. All they do is pay you back for putting in some patients.” Indeed, only about half of NAMDC’s sites had designated study coordinators at the time of our study. Recently, NAMDC has been taking steps to involve study coordinators more directly. At the 2015 face-to-face meeting, one of the few study coordinator attendees suggested involving study coordinators in protocol development to better anticipate practical implementation issues. A more general discussion of the study coordinator role in NAMDC ensued and the group voted to create a study coordinator committee.

15.4.1.1.3 Resources, Challenges, and Dilemmas

Deciding whether to add a site involves judgments about how best to use both NAMDC’s limited available funding and the time and energy of NAMDC members. Study participants favored inclusiveness but were well aware of these trade-offs.

Limited funding was the most pressing concern reflected in our study. For example, a large majority of survey respondents were moderately or very concerned that funding would be stretched too thinly if sites were added. Because the governance dilemmas posed by funding constraints are also relevant to the patient registry and biorepository action arena, we discuss them in Section 15.4.2.2.

Majorities of our survey respondents were also moderately or very concerned that adding sites would increase bureaucracy and make decision making more difficult. These problems can be mitigated through institutional design. The challenge is to cut down time spent in meetings and other administrative and decision making activities, while maintaining a highly collaborative and participatory community. NAMDC’s committee structure is one approach to this challenge. Though not fully implemented at the time of our study, the committee structure is designed to delegate tasks, encourage participation, and prepare topics for consideration by the group as a whole. The active Diagnostic, Pilot Project, and Training Program Committees appeared to be performing such functions effectively. Committee participation may also serve more general community-building purposes. A large majority of survey respondents agreed that NAMDC’s committee structure improves cooperation among researchers, while an interviewee described a particular example of a collaboration that emerged as a side benefit of working with another NAMDC member on a committee.

15.4.1.2 Promoting Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing

Interviewees emphasized the importance of pooling efforts to make progress on rare disease research. Informal knowledge sharing is easiest when researchers are in physical proximity or have preexisting relationships. NAMDC’s challenge is to promote collaboration and knowledge sharing among researchers at widely dispersed institutions, only some of whom know each other well.

Mitochondrial disease medicine is a small field, and most of NAMDC’s researchers were somewhat acquainted with one another before joining NAMDC. Nonetheless, one interviewee described the pre-NAMDC environment as “fragmented” and observed that “you would hardly ever see even two people work together,” while another observed that “in the old days … there seemed to be competing factions depending on where someone was situated in the country.”

While some interviewees remained dissatisfied that “much of the mitochondrial research is still single investigator driven and not community driven,” most study participants believed that NAMDC had improved knowledge sharing and collaboration significantly. As one interviewee put it, “what’s really different with NAMDC is there is much more collaboration rather than individual work.” Interviewees described NAMDC as a “very cohesive” and “congenial” community, in which members “have very healthy arguments, very healthy disagreements” without “the old-school mentality, like, ‘If I share my data, I’m going to get scooped and then I’m not going to get my pubs and then I’m not going to get tenure and then I’m going to die under a rowboat, poor’” Survey respondents also generally agreed that NAMDC is a “close-knit community” and that they collaborate and share research ideas with other NAMDC members more often since joining.

As a rough check on these impressions, we tabulated cross-institutional coauthorship between NAMDC members before and after 2011, when NAMDC was established. Before 2011, currently active NAMDC PIs had coauthored more than once with an average of only about two members outside their own institutions. That average rose to approximately six for the period after 2011 consistent, at least, with participants’ qualitative observations. Consortium membership may be particularly important for researchers at relatively less-known institutions. One PI reported that, “When the mitochondrial medicine society sent out a survey of which labs do you use we were not even listed. When I asked why we’re not listed they said, well we don’t know that you exist.” That PI had not previously coauthored more than once with any other NAMDC member but had done so with nine NAMDC members since 2011.

NAMDC’s members, at least, do not think that the enhanced cooperation and sharing among NAMDC members comes at the expense of cooperation with outside researchers. Not a single survey respondent agreed that NAMDC has made cooperation between members and nonmembers more difficult.

While some interviewees suggested that pre-NAMDC “fragmentation” among mitochondrial disease researchers was due to competitiveness, competitiveness does not seem to have created serious governance problems for NAMDC. As one interviewee put it:

I found that in the old days when I used to go to the meetings that not all [mitochondrial disease researchers] worked well together. That’s changed on a number of levels. So I think there seemed to be competing factions depending on where someone was situated in the country, and I think it was pretty obvious like a decade or so ago … [but now] it’s getting better … [because] people realize they have to work together on these rare disorders. That you can’t really be a silo out there because you don’t have the access to the patients and the funding is always an issue so it’s always better to work in a group to get these things accomplished.

An NIH representative concurred that competitiveness has not been a major hurdle for NAMDC. Rather, “the biggest issue for them is getting the data, seeing the patients, having the personnel to enter the data, having the [quality control].” Another interviewee similarly observed, “I haven’t seen a lot of backstabbing. I see them more as competing as a group against other areas of research.”

NAMDC appears to have increased collaboration and knowledge sharing primarily by providing infrastructure and coordination to facilitate it. One interviewee described NAMDC as

a mechanism that’s really very helpful in moving all of our goals forward. It’s … been synergistic because it’s helped pull us all together and it’s encouraging more research … It’s [provided] government funding to develop a longitudinal database which then can lead to all sorts of things because you can follow patient disease courses and you have a supply of patients for research. That just wouldn’t happen otherwise.

Another described NAMDC’s importance as a forum for building the mutual trust required for collaboration:

Coming to meetings like NAMDC is building those personal connections; there are a number of people here I now have collaborations with that are really not as much based on the formal structure of NAMDC, but the informal meeting and finding people and talking about things. I think that’s actually more effective than the formal structures. You can have formal structures and rely on everybody there, then you have a number of outliers who just don’t do what they say, that does not work. When you want to work with people that you know, when they say they’ll do something they actually will do it.

15.4.1.3 Recruiting and Training Mitochondrial Disease Clinical Researchers

RDCRN consortia are required to make efforts to “train[] investigators in clinical research of rare diseases.”Footnote 37 Members see these efforts as critical to NAMDC’s mission:

You have to train the next generation, because a lot of people in our consortium are in their seventies, and many are still practicing, but eventually they’re going to stop seeing patients. Then who is going to take care of these patients clinically and carry the mission forward?

There has to be a strong investment in training the next generation and attracting them to do rare-disorder research because the funding’s not as good. So, doing [pilot] projects within this [program,] I see as a benefit to get people interested in rare disorders. Because they can be more successful doing it as part of a consortium then trying to get R01, R21 on their own. They have the support of a group, and they have access to the patients. Once you get people interested in rare disorders, I think you can move the other things forward. If you can’t get them interested, then it’s not going to move forward.

NAMDC’s Training Program Committee oversees its formal fellowship program and is responsible for the design and execution of its training program curriculum. The NAMDC fellowship is unusual in that fellows complete coursework at University of California–San Diego and then rotate among several NAMDC sites for clinical and research practice, rather than training with a single group at one location. PIs at all participating sites belong to the Training Program Committee and participate in a monthly webinar during which trainees discuss their research and members make presentations about the research going on in their groups. Multiple interviewees emphasized the value of these webinars. The NAMDC community also facilitates informal training and mentoring. Many of our interviewees related stories of how senior researchers provided critical guidance and support at early stages of their careers. As one interviewee put it, “I wish I had this when I was a fellow … If there was NAMDC before, I wouldn’t have had to do a lot of things, just reinvent the wheel for myself all of the time.”

Recruiting new mitochondrial disease researchers can be challenging. NAMDC has received only about two to four fellowship applicants a year and would like to receive more. Moreover, NAMDC’s fellowship program is relatively new and still evolving. Some members questioned whether the rotation approach, despite its educational benefits, might deter potential applicants because of its disruption of the fellows’ personal lives. There was also a possibly related concern that a recent fellow had spent too much time doing data entry and not enough time creating “a body of work that can help this person’s career move forward.”

15.4.2 Developing and Managing a Shared Pool of Research Subjects, Patient Data, and Biological Specimens

NAMDC’s primary vehicle for overcoming the barriers posed by small numbers of geographically scattered rare disease patients is the NAMDC Patient Registry and Biorepository Study (7401 Protocol). All NAMDC sites take part, at least to some degree. The 7401 Protocol “is not itself a study, but rather a project to create infrastructure resources for laboratory studies, clinical trials, natural history studies, and other research endeavors.”Footnote 38 It consists of two related efforts, one collecting patient data and the other collecting biospecimens. As described in NAMDC’s 2014 renewal proposal, the Patient Registry

gathers baseline clinical, biochemical, and molecular genetic data as well as tracks the natural histories of the patients through the NAMDC Clinical Longitudinal study. The overall missions of the NAMDC Clinical Registry are to: better understand the spectrum and overlap of phenotypes for specific mitochondrial diseases; enable genotype/phenotype correlations; facilitate enrollment into clinical studies under NAMDC and other entities; and characterize the natural histories of mitochondrial diseases … Samples of blood, skin, and other tissues are being deposited into the NAMDC Biorepository.Footnote 39

Every RDCRN consortium is required to conduct a longitudinal study to characterize how its focal diseases develop over time.Footnote 40 The term “registry” is often used to indicate a database, such as the DMCC’s RDCRN Contact Registry,Footnote 41 where patients can indicate interest in being contacted to participate in clinical trials or other research. UMDF maintains a Mitochondrial Disease Community Registry, which is intended not only for that purpose but also to collect patient-reported data about symptoms, quality of life, and so forth.Footnote 42 While titled a patient registry, NAMDC’s 7401 Protocol is intended also to collect data for NAMDC’s longitudinal study.

DMCC PI Jeffrey Krischer explains that while both longitudinal studies and contact registries are used to “identify populations for interventional studies,” longitudinal studies are “physician enrolled with informed consent,” “hypothesis driven,” and “describe phenotypic variation,” while contact registries are “patient/family enrolled with online informed consent; collect “limited data” and may be used to provide information and as a “vehicle for epidemiological studies.”Footnote 43

Longitudinal study data feeds directly into research, ordinarily without further patient contact. Thus, care must be taken with data collection at the outset. Most basically, collection should reflect agreed-upon diagnostic criteria for determining whether to include a given patient’s data in a study. Thus, NAMDC has attempted to “create[] NAMDC Research Diagnostic Criteria for mitochondrial diseases with strict benchmarks for definite, probable, possible, or unlikely levels of diagnoses.”

In this section we discuss three important NAMDC action arenas related to creating a pool of patients, data, and biospecimens for NAMDC’s longitudinal study and other potential research: (1) developing the NAMDC Research Diagnostic Criteria, (2) recruiting patients and collecting the relevant data and biospecimens, and (3) managing and using the pooled research resources.

15.4.2.1 Diagnostic Criteria

“One of the great problems in our field is diagnosing mitochondrial disease. It’s not one disease but many, probably hundreds or more. It’s a dilemma.” Diagnosis has been a major action arena for NAMDC. Even for clinical purposes, diagnosis remains a work-in-progress, as reflected in the MMS Consensus Statement. Moreover, these criteria may differ from what NAMDC requires for research purposes:

Frankly, I think among rare diseases, mitochondrial diseases are among the most over-diagnosed and under-diagnosed because they’re so diverse. They’re under-diagnosed because people just don’t recognize them, and then they’re over-diagnosed because whenever there’s a patient with a complex multi-systemic disease, people throw up their hands and say, “Must be a mitochondrial disease.” We felt obliged to really set up criteria for our sake, for stratifying the registry, the patients in a registry. Also for research purposes, because we take the possible and probable patients and we may do additional genetic or molecular studies to define them better. And also just to say that there are a couple of patients that are very unlikely to have mitochondrial disease even though they were diagnosed by supposed experts who entered all these patients into the registry. [W]e’re trying to use that as an educational tool so that when we put the patients through the diagnostic criteria, or their information through the criteria, we send back a letter to the site investigators and inform them what their NAMDC diagnosis is and level of probability. We’re actually going through this exercise, and we’re having people reevaluate their original diagnosis to see if they agree with the NAMDC criteria or not and if not why, and we’re revising our diagnostic criteria. It’s a back-and-forth activity here that’s in progress.

Because mitochondrial disease research is still at an early stage, clinical diagnoses can be controversial, as one interviewee explained:

Why do you need diagnostic criteria [when] you have experts diagnosing people? There’s two [reasons]: One is … there’s very few of these experts, and so if they feel that mitochondrial disease is under diagnosed, you want to give [the diagnostic criteria] to people who aren’t experts so they can check off the checklist and say, “Oh, you’ve got mitochondrial disease,” or, “You don’t.” But the other, which goes unsaid, is that there’s very little agreement between these experts … I mean some of them are unambiguous; the very syndromes are unambiguous, but a lot of them are ambiguous, and there’ve been long, not fights, but vigorous conversations about how to define each one. And still, we had … a version that we came up with and then we ran it against the actual patient population, and the results of that were very controversial.

Ultimately, the value of the NAMDC patient registry as an input for research is contingent on the quality of the data included and the reliability of the diagnostic criteria. Thus, as one interviewee explained, “You want as clean a population as you can study, and so the diagnostic criteria are much tighter. That’s one thing that NAMDC [focuses] on. That’s why you have this issue of research diagnosis.”

An initial set of NAMDC Diagnostic Criteria was developed by a committee of NAMDC’s initial membersFootnote 44 and programmed into NAMDC’s online data collection system. A significant number of disagreements with clinical diagnoses were uncovered, leading to a concerted effort to uncover the sources of discrepancy and validate or revise the NAMDC Diagnostic Criteria. The validation effort involved surveying NAMDC investigators for feedback and tasking a consultant researcher with detailed review of cases where clinical diagnoses disagreed with NAMDC’s automated diagnoses.

The consultant uncovered several disagreement scenarios. Sometimes the NAMDC criteria were “too strict,” for example, when patients with a particular phenotype were not assigned the correct diagnosis because some data, such as age of onset, was not recorded. NAMDC attempted to address this problem by structuring the data entry process to “inform the physician what fields in the eCRF must have data entered” to obtain a particular NAMDC Criteria Diagnosis. Ambiguities or misunderstandings during data entry also could cause disagreement:

In my head, if I have liver disease, I would check off hepatopathy, or something. But if a person who does not understand the term hepatopathy is entering the data for you, he or she sees a spreadsheet, the liver enzymes are abnormal, all the liver functions are abnormal, but there is no place to enter the liver enzymes are abnormal. So he/she does not mark that column there is liver involvement. The computer looks at it and says how can you call it Alpers when you don’t have liver involvement? I am rejecting it.

The NAMDC criteria were also sometimes “too rigid,” making it hard “to factor in the evolution of the disease in some patients.” Sometimes, the automated algorithm was simply missing “that sixth sense” that clinicians develop through experience.

Even as NAMDC works to improve and validate its diagnostic criteria, the science continues to evolve. As one interviewee explained: “So one of the inherent catch-22s in all this is that you set up criteria based upon what you know. But if you only know 15 percent of the causes of diseases then your criteria are only going to let you capture that 15 percent. It’s not going to let you capture the unknown.” Moreover, the data fields chosen for the NAMDC Diagnostic Criteria, though many, are a small fraction of possible choices and were likely to reflect historical bias: “For example, the new mito disease that we just discovered it’s showing to affect the bones. We don’t ask one question about bones [in the Diagnostic Criteria]. Zero. Zip … So we would never capture the disease that involved the bones because we never asked.” Scientific evolution is particularly rapid with respect to genetic markers, where there is “just an ever-changing landscape … Even as we wrote the criteria four years ago until now, we’ve had at least probably another 50 genes added.” The bottom line, in the opinion of one interviewee, is that mitochondrial disease diagnosis is “never going to be a perfect science.”

NAMDC’s experience highlights how unanticipated layers of knowledge dilemmas can emerge in a consortium setting. NAMDC’s Diagnostic Criteria were developed as a research tool for constructing the patient data pool and enabling NAMDC’s planned research, yet the development of accurate and workable criteria has itself become a dynamic and complex action arena facing many challenges. NAMDC has grappled with the diagnosis dilemma through formal and informal governance institutions. NAMDC’s Diagnostic Committee was formed as an ad hoc group but integrated into the formal committee structure when it was instituted. The validation process evolved informally. For example, when asked who decided on the process that NAMDC’s consultant would use to conduct her evaluation and who picked her to do it, one interviewee responded, “It just is one of these things that just evolved organically.”

15.4.2.2 Creating a Pool of Research Subjects, Patient Data, and Biospecimens

NAMDC’s Patient Registry aggregates medical and family histories, diagnostic test results, and other information from patients who enroll in the study. Clinical sites collect and enter the data, which is pooled using Columbia’s data management facilities and shared with the DMCC, as NIH requires. Biorepository samples of blood, skin, and other tissues are collected by site researchers and submitted to and maintained at the Mayo Clinic.

15.4.2.2.1 The NAMDC Patient Registry

NAMDC initially set a goal of enrolling 15 patients per month in its registry, aiming eventually for a total of 1000 patients. The first patients were enrolled in June 2011. By April 2012, four NAMDC sites had enrolled a total of 121 patients. NAMDC has exceeded its monthly recruitment goal since May 2012. By October 2015, 844 patients had been enrolled from 17 sites. Recruitment numbers vary substantially among sites, with cumulative enrollments as of October 2015 ranging from 136 to 7, and average monthly enrollments ranging from 2.6 to 0.2.

Enrollment numbers do not tell the whole story. For NAMDC’s data pool to function as intended, each patient’s data must be sufficiently complete to confirm a diagnosis using the NAMDC Diagnostic Criteria. By August 2012, that was the case for only about half the enrolled patients, while at four sites data was incomplete for every patient. Over time, this picture improved dramatically. By October 2015, data entry was sufficient for nearly 90 percent of enrolled patients, average site compliance rate was 90 percent, and the lowest compliance rate was 62 percent.

If NAMDC’s patient registry data is to be used for a longitudinal study, patients also must be followed over time and data entered at appropriate intervals. The 7401 Protocol calls for yearly follow-up visits. By December 2014, however, only 17 percent of scheduled follow-ups had been completed, the average site follow-up rate was 25 percent and only about half of the sites had completed any follow-ups. By October 2015, things had improved only slightly; only 25 percent of scheduled follow-ups had been completed overall and the average follow-up rate was 36 percent.

15.4.2.2.2 The NAMDC Biorepository