Policy Significance Statement

Practitioners, policymakers, and designers may consider the findings from this paper to examine the viability of the potential contributions suggested, deliberate policies around open data intermediaries, and develop their organizational and business models.

1. Introduction

Open data are “data that can be freely used, shared, and built on by anyone, anywhere, for any purpose” (OKF, 2013). Such data promise various benefits, including stimulating innovation, improving transparency, and enhancing the reproducibility and dissemination of scientific research (Molloy, Reference Molloy2011; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Charalabidis and Zuiderwijk2012; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Wulder, Roy, Woodcock, Hansen, Radeloff, Healey, Schaaf, Hostert, Strobl, Pekel, Lymburner, Pahlevan and Scambos2019). Open data has demonstrated its value in various domains. For instance, open data provided by the Global Forest Watch has been used by environmental advocates in the Philippines to support the enactment of the National Mangrove Forests Conservation and Rehabilitation Act (Camero, Reference Camero2015), by indigenous groups in Peru to track and report forest loss in the Amazon (Moloney, Reference Moloney2021), and by international researchers to study global forest fire trends over time (Tyukavina et al., Reference Tyukavina, Potapov, Hansen, Pickens, Stehman, Turubanova, Parker, Zalles, Lima, Kommareddy, Song, Wang and Harris2022; Johnson, Reference Johnson2023). The implementation of an open procurement data policy in the European Union (EU) has led to more competitive bidding, which has been attributed to increased scrutiny by nongovernmental organizations and investigative journalists, as well as learning by national procurement regulators (Duguay et al., Reference Duguay, Rauter and Samuels2023).

Nevertheless, various challenges exist in preparing, disseminating, processing, and reusing open data (Conradie and Choenni, Reference Conradie and Choenni2014; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Sieber, Scassa, Stephens and Robinson2017; Sugg, Reference Sugg2022). These include those faced by open data providers, such as scattered data management (Linders, Reference Linders2013; Ma and Lam, Reference Ma and Lam2019), resource constraints (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Charalabidis and Zuiderwijk2012; Nikiforova and Zuiderwijk, Reference Nikiforova and Zuiderwijk2022) and the lack of a convincing business case for publishing open data (Barry and Bannister, Reference Barry and Bannister2014; Cahlikova and Mabillard, Reference Cahlikova and Mabillard2020), and those faced by open data users, such as poor or inconsistent open data quality (Crusoe et al., Reference Crusoe, Simonofski, Clarinval and Gebka2019; Huijboom and Van den Broek, Reference Huijboom and Van den Broek2011), underdeveloped data skills (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Charalabidis and Zuiderwijk2012; Zuiderwijk and Reuver, Reference Zuiderwijk and Reuver2021), and limited complementary technologies for using open data (Temiz et al., Reference Temiz, Holgersson, Björkdahl and Wallin2022; Zuiderwijk et al., Reference Zuiderwijk, Janssen, Choenni, Meijer and Alibaks2012). More recent studies seem to reveal similar challenges to those identified a decade ago persist (to illustrate this, we cite studies published before/in 2013 and after 2013 for each of the aforementioned examples). Therefore, it is imperative to investigate how to address these challenges. As such, this paper asks what the contributions of open data intermediaries may be in this regard.

Open data intermediaries can be defined as “third-party actors who provide specialized resources and capabilities to (i) enhance the supply, flow, and/or use of open data and/or (ii) strengthen the relationships among various open data stakeholders” (Shaharudin et al., Reference Shaharudin, van Loenen and Janssen2023). Notably, they serve a pivotal role in the effective distribution of resources in the open data ecosystem (ODE) (Chattapadhyay, Reference Chattapadhyay2014). Open data intermediaries could be a public organization, a for-profit company, a nonprofit organization, a public–private partnership, or various other types of entities undertaking a wide range of tasks for different objectives (Andrason and van Schalkwyk, Reference Andrason and van Schalkwyk2017; Dumpawar, Reference Dumpawar2015; Enaholo and Dina, Reference Enaholo and Dina2020; González-Zapata and Heeks, Reference González-Zapata and Heeks2015; Schrock and Shaffer, Reference Schrock and Shaffer2017; Shaharudin et al., Reference Shaharudin, van Loenen and Janssen2023). They include software providers that integrate preprocessed open data in their systems, nonprofit organizations that compile, contextualize, and visualize open data for public consumption, and crowdsourcing platforms that facilitate the contribution and reuse of open data.

Despite the crucial role of open data intermediaries, research on their potential contributions to addressing persistent challenges in the ODE remains lacking. Most studies have only investigated their existing activities. While this baseline understanding is undoubtedly important, the next necessary step is to explore what could be done by open data intermediaries for the benefit of the entire ODE. One pathway toward this end is to explore the connections between challenges in the ODE and potential contributions by open data intermediaries to address them. Hence, the research question of this paper is presented as follows: What are the potential contributions of open data intermediaries to address various challenges in the ODE? We answer this question within the context of the European Union (EU). The legal regime of open data in the EU is rather specific since many organizations are legally obligated to publish and facilitate the reuse of open data. Failure to comply may result in EU member states facing legal consequences brought by the European Commission (EC), including heavy financial penalties.

The structure of this paper is as follows. The next section, Section 2, outlines the conceptual framework, particularly on the ODE and open data intermediaries. Section 3 presents the research methodology. Section 4 presents the findings. Section 5 reflects on the findings. Lastly, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Conceptual framework

This section lays out the conceptual framework to motivate the need to explore the potential contributions of open data intermediaries and situate this study within the broader discourse on open data. Subsection 2.1 discusses the ODE as an analytical tool describing relationships between actors involved in open data. We do this by reviewing claims around the ODE, as advocated by open data researchers and practitioners, and comparing them with theoretical concepts from the broader field of science and technology studies (STS), specifically those associated with actor–network theory (ANT). Once we have established the scope of an ODE, Subsection 2.2 discusses the “sustainability” of an ODE. In particular, we review the features of sustainable open data ecosystems and the challenges faced by different open data actors that could disrupt the sustainability of an ODE. In Subsection 2.3, we discuss open data intermediaries as a category of actors in an ODE. We review their types, activities, and roles toward a sustainable ODE.

2.1. Open data ecosystem (ODE)

Based on empirical studies of the U.K. government’s open data initiatives and the International Aid Transparency Initiative, Davies (Reference Davies2011) argued that successful value generation from open data relies on more than just the dataset; it also relies on the “mobilisation of a wide range of technical, social and political resources, and on interventions […] [to] support coordination of activity around datasets” (Davies, Reference Davies2011, p. 1). Thus, he advocated for the ODE as an analytical lens through which “the emergent, autonomous and self-organising components” are “linked together in local and global feedback loops and developing according to local specialisations and adaptation rather than top-down design” (Davies, Reference Davies2011, p. 3). According to Davies, the “ecosystem” metaphor is useful in describing the interrelations of open data actors and devising interventions to increase cooperation and interaction among actors, just as the metaphor is used in other fields such as economics and political science. This dual function of the metaphor was also emphasized by Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Pardo and Cook2012, p. 907): “Although ecosystems are naturally occurring phenomena and the metaphor may be applied to any existing socio-technical domain, they can also be seeded, modelled, developed, managed, that is, intentionally cultivated for the purpose of achieving a managerial and policy vision.”

Csáki (Reference Csáki, Kő, Francesconi, Anderst-Kotsis, Tjoa and Khalil2019) succinctly defined an ODE as a “way of looking [emphasis added] at how participating actors and groups create shared meaning and generate value around open data and how the structural properties of their interactions shape this process, which in turn enables or constrains the growth and health of the ecosystem itself” (Csáki Reference Csáki, Kő, Francesconi, Anderst-Kotsis, Tjoa and Khalil2019, p. 19). This definition evokes similarities with how ANT is described by one of its cofounders, which is “a disparate family of material-semiotic tools, sensibilities and methods of analysis [emphasis added] that treat everything in the social and natural worlds as a continuously generated effect of the webs of relations [emphasis added] within which they are located” (Law, Reference Law and Turner2008, p. 141). Thus, an ODE can be considered a specific application of the ANT, rooted in the larger field of STS. From this perspective, an ODE is not an isolated nor necessarily novel analytical approach to a socio-technical network but one that can draw theoretically and empirically grounded insights from other types of networks, including information systems [e.g., Díaz Andrade and Urquhart (Reference Díaz Andrade and Urquhart2010); Nehemia-Maletzky et al. (Reference Nehemia-Maletzky, Iyamu and Shaanika2018); Walsham (Reference Walsham, Lee, Liebenau and DeGross1997)].

A fundamental notion underpinning ANT is the participation of humans and nonhumans in a network, including technological artifacts (in the case of open data, e.g., data portals, application programming interfaces, and data standards), not only passively as a resource or constraint, but also actively influencing the dynamic interactions in the network (Callon and Law Reference Callon and Law1997). This mirrors the conceptual elements of the ecosystem identified by Oliveira and Lóscio (Reference Oliveira and Lóscio2018), namely resources, roles, actors, and relationships. Resources can be datasets, data-based software, and hardware, which may be exchanged individually or in combination, through relationship transactions. A role is a function of an actor in the ecosystem. Actors are autonomous entities such as businesses, public institutions, and individuals serving one or more specific roles. Relationships are the interactions among actors in the ecosystem. Notably, Oliveira and Lóscio (Reference Oliveira and Lóscio2018) made a distinction between roles and actors: actors are not wedded to any particular roles.

Poikola et al. (Reference Poikola and Kola2011) drew attention to the autonomy yet interdependency of actors in an ODE. As they put it, the “ecosystem evokes an image of the well-being of the entity and, on the other hand, fulfilling one’s own needs through the richness and vitality of the ecosystem” (Poikola et al., Reference Poikola and Kola2011, p. 14). They also highlighted the ever-changing nature of an ecosystem: “With the ecosystem, we wish to highlight not only the technological systems and institutionalized organisations but also the living, dynamically changing network of interaction [emphasis added]” (Poikola et al., Reference Poikola and Kola2011, p. 14). This hybridity of self-interested yet interdependent actors is an essential notion of ANT asserting that “every stable social arrangement is simultaneously a point (an individual) and a network (a collective)” (Callon and Law Reference Callon and Law1997, p. 165).

2.2. Sustainable ODEs and current challenges

One of the empirical focuses of ANT is “to trace and explain the processes whereby relatively stable networks of aligned interests are created and maintained, or alternatively to examine why such networks fail to establish themselves” (Walsham, Reference Walsham, Lee, Liebenau and DeGross1997, p. 469). In the same manner, researchers are investigating factors that contribute to a sustainable ODE, where stable networks of open data actors’ aligned interests are created and maintained (adopting the words of Walsham). Notably, van Loenen et al. (Reference van Loenen, Zuiderwijk, Vancauwenberghe, Lopez-Pellicer, Mulder, Alexopoulos, Magnussen, Saddiqa, de, Crompvoets, Polini, Re and Flores2021) suggested the key features of a sustainable ODE, which can be summarized as user-driven (open data supply matches the demands of users of different types and domains), circular (all actors mutually create and capture value), inclusive (all actors, not only government organizations, but are also incentivized to contribute open data and participate in ecosystem processes), and skills-based (appropriate data skills and competencies are applied) [comparable to Heimstädt et al. (Reference Heimstädt, Saunderson and Heath2014)]. To achieve a sustainable ODE, Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Pardo and Cook2012) recommended strategic ecosystem thinking, which involves identifying the actors in the ecosystem, understanding the relationship between these actors, identifying the resources that each actor must engage with others, and observing the indicators that represent ecosystem health.

Numerous empirical studies and reviews have highlighted myriad challenges related to the preparation, dissemination, and reuse of open data (Bonina, Reference Bonina2013; Conradie and Choenni, Reference Conradie and Choenni2014; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Sieber, Scassa, Stephens and Robinson2017; Sugg, Reference Sugg2022; Toogood, Reference Toogood2021). These challenges endanger the sustainability of ODEs. Some of them are encountered by open data providers, such as scattered data management (Linders, Reference Linders2013; Ma and Lam, Reference Ma and Lam2019), resource constraints (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Charalabidis and Zuiderwijk2012; Nikiforova and Zuiderwijk, Reference Nikiforova and Zuiderwijk2022), and the lack of a convincing business case for publishing open data (Barry and Bannister, Reference Barry and Bannister2014; Cahlikova and Mabillard, Reference Cahlikova and Mabillard2020), while other challenges are experienced by open data users, such as poor or inconsistent open data quality (Crusoe et al., Reference Crusoe, Simonofski, Clarinval and Gebka2019; Huijboom and Van den Broek, Reference Huijboom and Van den Broek2011), underdeveloped data skills (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Charalabidis and Zuiderwijk2012; Zuiderwijk and Reuver, Reference Zuiderwijk and Reuver2021), and limited complementary technologies for using open data (Temiz et al., Reference Temiz, Holgersson, Björkdahl and Wallin2022; Zuiderwijk et al., Reference Zuiderwijk, Janssen, Choenni, Meijer and Alibaks2012). Research in this area is already quite saturated, with new studies highlighting similar challenges to those identified a decade prior. Therefore, the next step is to investigate how to overcome these challenges in practice.

From an ecosystem perspective, all actors, not limited to open data providers, can and should contribute to addressing challenges in ODEs. Actors in an ODE are individually and collectively affected by each other; hence, solving issues in an ODE is not a “one-person job.” This understanding lays the groundwork for our research question: What could open data intermediaries contribute toward a sustainable ODE? We adopt the features that van Loenen et al. (Reference van Loenen, Zuiderwijk, Vancauwenberghe, Lopez-Pellicer, Mulder, Alexopoulos, Magnussen, Saddiqa, de, Crompvoets, Polini, Re and Flores2021) proposed (i.e., user-driven, circular, inclusive, and skills-based features) as our benchmark for a sustainable ODE. This is because, to the best of our knowledge, the paper is the first to identify the features of a sustainable ODE at the conceptual level. It is similar to—but more refined than—the features proposed by Heimstädt et al. (Reference Heimstädt, Saunderson and Heath2014), who drew inspiration from the business ecosystem literature. However, we must first determine what the open data intermediaries are.

2.3. Open data intermediaries

Based on a systematic literature review, Shaharudin et al. (Reference Shaharudin, van Loenen and Janssen2023) proposed a theoretical definition of open data intermediaries as “third-party actors who provide specialised resources and capabilities to (i) enhance the supply, flow, and/or use of open data and/or (ii) strengthen the relationships among various open data stakeholders.” The intermediary is a crucial concept in ANT. However, ANT differentiates intermediaries, a messenger that “transports meaning or force without transformation” from mediators that “transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry” (Latour Reference Latour2007, p. 39). Our conceptualization of open data intermediaries does not make such distinction (i.e., both ANT’s intermediaries and mediators are termed “open data intermediaries” in an ODE) since this is how the term is conventionally used in the literature as an umbrella term for heterogeneous types [for a review, see Shaharudin et al. (Reference Shaharudin, van Loenen and Janssen2023)]. Regardless, ANT highlights the importance of intermediaries/mediators as match-makers for situations in which “people, goods and services are brought together” (Goodchild and Ferrari Reference Goodchild and Ferrari2024, p. 107). In the same vein, Chattapadhyay (Reference Chattapadhyay2014) argued that a vital aspect of the ODE lies in the efficient circulation of resources, with open data intermediaries serving a pivotal role in this regard. The role of open data intermediaries is instrumental in the access to and use of open data (González-Zapata and Heeks Reference González-Zapata and Heeks2015; Neves et al. Reference Neves, de Castro Neto and Aparicio2020) and in connecting open data actors (Mayer-Schönberger and Zappia Reference Mayer-Schönberger and Zappia2011; Yoon et al. Reference Yoon, Copeland and McNally2018). Furthermore, since the ODE emphasizes the self-organization of actors (Davies Reference Davies2011; Oliveira and Lóscio Reference Oliveira and Lóscio2018), open data intermediaries are crucial in mitigating information asymmetry between actors.

As a point of clarification, open data intermediaries should certainly include “open data” in their activities despite their end product not necessarily being open [the same emphasis was notably made by van Schalkwyk et al. (Reference van Schalkwyk, Cañares, Chattapdhyay and Andrason2016, p. 12)]. While this may seem obvious, being involved with data shared on a case-to-case basis through individual arrangements and not with open data as it is conventionally defined, as in the case of certain forms of data collaboratives (Susha et al., Reference Susha, Janssen and Verhulst2017) or boundary organizations (Perkmann and Schildt, Reference Perkmann and Schildt2015), does not make such actors open data intermediaries. As similarly highlighted by scholars of ANT (Klecuń, Reference Klecuń, Kaplan, Truex, Wastell, Wood-Harper and DeGross2004; Lee and Hassard, Reference Lee and Hassard1999), a delimitation based on concrete practices and functioning for empirical study is necessary to avoid dealing with an “endless chain of association” (Müller, Reference Müller2015, p. 30).

Various types of actors serve the role of open data intermediaries, including civil society organizations (Meng et al., Reference Meng, DiSalvo, Tsui and Best2019; Sangiambut and Sieber, Reference Sangiambut and Sieber2017), companies (Andrason and van Schalkwyk, Reference Andrason and van Schalkwyk2017; Germano et al., Reference Germano, de Souza and Sun2016), the media (Enaholo and Dina, Reference Enaholo and Dina2020; Johnson and Greene, Reference Johnson and Greene2017), researchers (Corbett et al., Reference Corbett, Templier, Townsend and Takeda2020; Park and Gil-Garcia, Reference Park and Gil-Garcia2017), and government organizations (Hablé, Reference Hablé2019; Meijer and Potjer, Reference Meijer and Potjer2018). They undertake various tasks, deploying different types of resources based on their specialization, such as augmenting data by integrating open data with non-open data (Andrason and van Schalkwyk, Reference Andrason and van Schalkwyk2017; Corbett et al., Reference Corbett, Templier and Takeda2018), developing open data-based products such as mobile apps (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Johnson and Shookner2016; Kim, Reference Kim2018), contextualizing open data into digestible information (Corbett et al., Reference Corbett, Templier and Takeda2018; Meng, Reference Meng2016), and providing training to end-users (Enaholo, Reference Enaholo, van Schalkwyk, Verhulst, Magalhaes, Pane and Walker2017; Meng et al., Reference Meng, DiSalvo, Tsui and Best2019). Although the actors referred to as open data intermediaries do not necessarily undertake activities solely related to open data, open data are certainly part of their intermediation activities [see the review by Shaharudin et al. (Reference Shaharudin, van Loenen and Janssen2023)].

To date, the relevant literature has primarily investigated the existing activities of open data intermediaries. Recognizing that persistent challenges related to the preparation, dissemination, and use of open data must be resolved, and building upon the ecosystem understanding that all actors can and should contribute to addressing these challenges, the following question is relevant: What are the potential contributions of open data intermediaries in addressing challenges in the ODE? This insight is currently missing from the literature and thus represents what this paper aims to offer.

3. Research methodology

This paper focuses on the EU context due to the shared legal regime concerning open data, which enables a more contextual interpretation of the findings. The EU Open Data and the Re-use of Public Sector Information Directive (Open Data Directive) was published in 2019, and EU countries were required to transpose this directive into national laws, regulations, and administrative provisions by July 2021 (European Parliament and Council of the European Union Directive (EU), 2019). This directive is a recast to the earlier Reuse of Public Sector Information (PSI) Directive 2003, and it establishes a set of minimum rules (including technical aspects) governing the reuse of data held by public bodies and “public undertakings” (including nonpublic entities operating in the water, energy, transport, and postal services sectors), as well as research data. The directive also lists specific high-value datasets across six thematic categories, four of which constitute spatial datasets (geospatial, earth observation and environment, meteorological, and mobility), while the remaining two are statistics and companies and company ownership. EU countries that fail to comply with this directive may face legal consequences brought by the EC, including heavy financial penalties. In fact, the EC referred several countries to the Court of Justice of the EU last year due to noncompliance with the Open Data Directive (European Commission 2023). This legal framework makes open data in the EU context rather specific since many organizations are legally obligated to publish and facilitate the reuse of open data.

Open data intermediaries are not to be confused with the “data intermediaries” established within the EU Data Governance Act framework (European Parliament and Council of the European Union Regulation (EU), 2022). As written (e.g., Item 10 of the Preamble), this Act does not apply to open data that falls under the Open Data Directive. Data intermediaries in the Data Governance Act are not allowed to use the data they intermediate (e.g., by developing products based on these data) and can only facilitate data sharing between parties. This is different from open data intermediaries, which can be users of open data (even for financial profit) because the data are already open.

This study adopted a qualitative research approach. It does not seek to offer generalizable quantitative sample-to-population findings nor suggest any causal relationships. Instead, it aims to pave the way for new areas of inquiry and interventions regarding the potential contributions of open data intermediaries for a sustainable ODE. There are two stages in the methodology. In Stage 1, we gathered data through semi-structured interviews involving ten interviewees from eight organizations representing open data providers, intermediaries, and a data standard body. From these interviews, we derived challenges in the ODE and the potential contributions of open data intermediaries (Section 3.1). In Stage 2, we explored the links between the individual potential contributions of open data intermediaries and specific challenges in the ODE that they can address. We validated these links with four organizations we interviewed in Stage 1 and nine additional open data practitioners and researchers (Section 3.2). Guided by the ecosystem perspective, where actors are interrelated, we involved representatives of diverse roles (open data providers, intermediaries, users, and researchers) in Stages 1 and 2.

3.1. Stage 1: semi-structured interviews

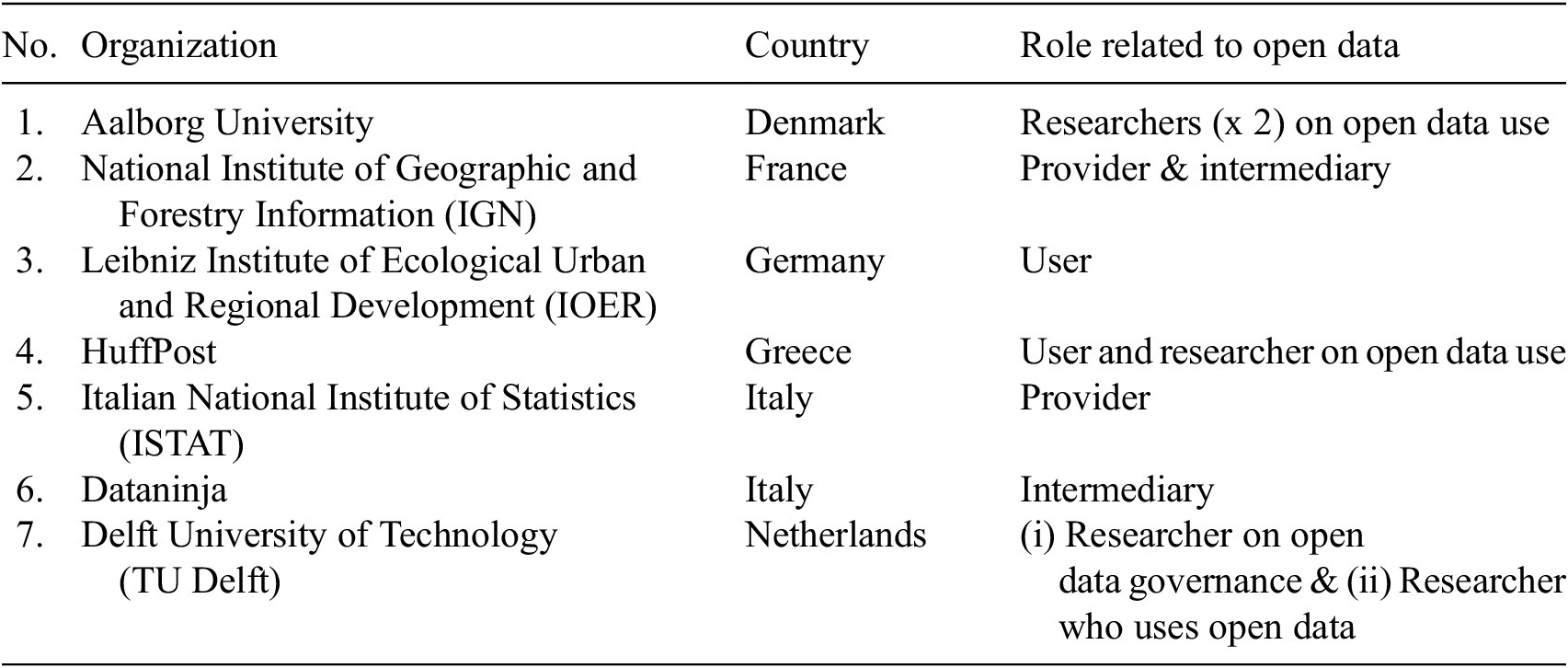

We conducted semi-structured interviews with ten experts from eight organizations based in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain, representing open data providers, intermediaries, and a data standard body between May and July 2023 (Table 1). These organizations were selected based on purposive sampling, in which we aimed to obtain insights from organizations that could provide information on the challenges in ODE and the potential contributions of open data intermediaries. Six out of the eight organizations are spatial data organizations because four out of six thematic categories of the high-value datasets listed under the EU Open Data Directive framework constitute spatial datasets.

Table 1. List of interviewee organizations

The individual interviewees are involved in formulating open data legislation at the national and EU levels, fulfilling the requirements of open data legislation, and coordinating open data stakeholders’ engagements. Seven of the ten interviewees have at least 10 years of experience in dealing with open data. The minimum open data experience among all of the interviewees is 5 years. All interviews were conducted online except for two, of which one was conducted in person, and another one in writing. We shared the informed consent form (reviewed by our university’s Human Research Ethics Committee and in compliance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation) and the tentative questions for each interviewee several days before the interview.

We asked questions across four areas (i) the background of the interviewee and their organization in relation to open data; (ii) their perception of the value of open data and its benefits and costs to their own organization; (iii) their perceptions of the sustainability of the ODE, challenges in the ODE, and potential remedies; (iv) their perceptions of the current and potential contributions of open data intermediaries. However, the questions were not exactly the same for each interview since they were semi-structured. In semi-structured interviews, interviewers ask practical, customized, open-ended questions in a conversation-like manner without expecting specific answers, thereby allowing interviewees to speak freely and fully (Magnusson and Marecek, Reference Magnusson and Marecek2015). Since the ODE is a rather abstract concept, we offered its working definition to interviewees as “a network of interdependent yet self-interested open data actors” to guide the interviews. The interview guide can be found in the Supplementary Appendix and can also be found here (with de-identified interview transcripts and the informed consent form template): https://doi.org/10.4121/d7dd11e0-7c6c-49db-946a-ffe71520f8fd.v1. As an additional privacy protection measure, the order of the de-identified transcripts in the repository differs from that in Table 1.

We coded the interview data inductively (Linneberg and Korsgaard, Reference Linneberg and Korsgaard2019) with the aid of ATLAS.ti software. There are two categories of codes (i) challenges in ODEs and (ii) potential contributions of open data intermediaries. The coding results can be found here: https://doi.org/10.4121/d7dd11e0-7c6c-49db-946a-ffe71520f8fd.v1. We opted for the inductive approach to derive the challenges in ODEs and the potential contributions of open data intermediaries close to the context the interviewees referred to, without being cognitively restricted by preconceived vocabularies. This contextual understanding is crucial in making informed decisions when linking the two to avoid speculating at a very abstract level.

3.2. Stage 2: analysis & validation

In Stage 2, we linked the individual contributions of open data intermediaries to the challenges in ODEs based on the data derived in Stage 1. To validate our analysis, we requested feedback from all of our interviewees; four out of eight organizations responded with their input (organizations 1, 6, 7, and 8 in Table 1). We also obtained feedback from nine other open data practitioners and researchers (Table 2). None of those listed in Table 2 are the authors of this study. In total, we received 13 inputs during our validation exercise in February 2024. Eleven of those were done in writing, where we shared the initial version of Table 5 (with the description for each item) and validators edited it by suggesting new links between the challenges of ODEs and potential contributions of open data intermediaries where they considered appropriate and removing initial links where they considered otherwise. They also added new challenges in ODEs and the potential contributions of open data intermediaries that were not listed in the initial version but deemed relevant. The other two validations (with organization 1 in Table 1 and organization 6 in Table 2) were performed through online meetings, where we discussed the table with the validators.

Table 2. List of additional validators’ organizations (aside from those interviewed)

Based on the input of the 13 validators, we evaluated the individual link suggestions. We considered each suggestion by speculating a case where the suggestion could be materialized. If there is such a case, we would accept the suggestion unless there is a counterargument against it (i.e., the contribution unlikely addresses the challenge). Where appropriate, we merged the new challenges and contributions proposed by validators (e.g., we merged develop common standards proposed by a validator with transform data into open standards as one of the potential contributions). We also added new links that were not directly suggested by validators but are appropriate and consistent with the general insights and reasoning offered by validators. Finally, we generated the mapping of potential contributions of open data intermediaries and the ODE challenges that they could address (Table 5).

Most of the experts engaged in this study (in Stages 1 and 2) are from the public sector, which may represent a limitation. However, these experts have rich experience in open data accumulated over many years in various capacities, including in coordinating open data stakeholder engagements. The organizations they represent are not only open data providers but also open data intermediaries and users. Notably, this paper does not claim to offer exhaustive lists of ODE challenges and the potential contributions of open data intermediaries (if that is even possible), nor does it seek to establish causal relationships.

4. Findings

Section 4.1 discusses the challenges in ODEs, while Section 4.2 discusses the potential contributions of open data intermediaries and connects them with the challenges they may address in ODEs. We derived the challenges in the ODE and the potential contributions of open data intermediaries from the interviews. Then, we validated the connections proposed between the two with input from some of the interviewees and additional experts.

4.1. Challenges in the ODE

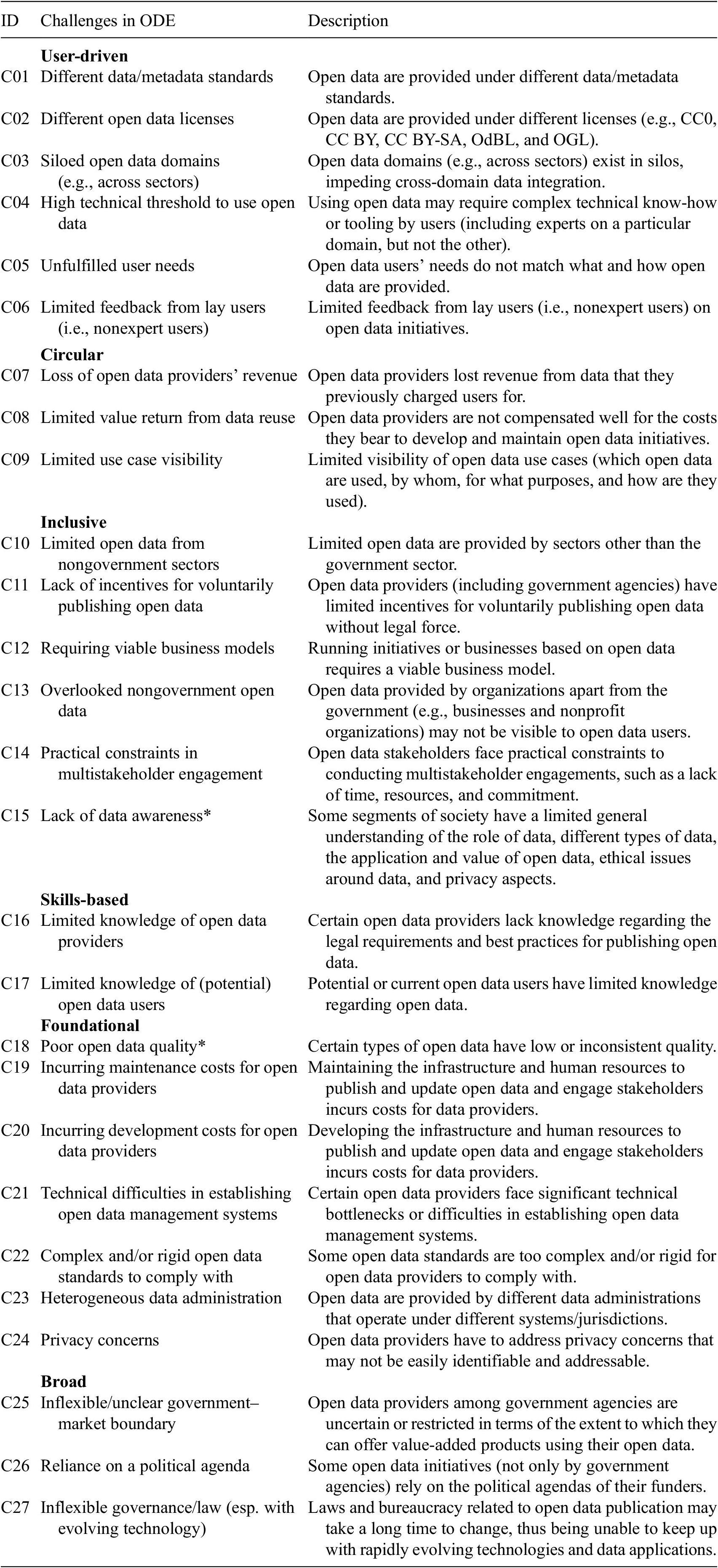

Table 3 presents challenges in the ODE identified from the interviews. We attempted to categorize them based on the key features of a sustainable ODE suggested by van Loenen et al. (Reference van Loenen, Zuiderwijk, Vancauwenberghe, Lopez-Pellicer, Mulder, Alexopoulos, Magnussen, Saddiqa, de, Crompvoets, Polini, Re and Flores2021), namely user-driven (open data supply matches the demand of users of different types and domains), circular (all actors mutually create and capture value), inclusive (all actors, not only government organizations, but are also incentivized to contribute open data and participate in ecosystem processes), and skills-based (appropriate data skills and competencies are applied). This form of categorization helps to show which challenges threaten which specific features of a sustainable ODE. However, we found that some challenges do not fit well into any of the four proposed features. Those that do not fit are either very foundational challenges around data management systems (categorized as “foundational”) or those associated with broader political factors beyond open data (categorized as “broad”). A sample quote from the interviews for each of the challenges is presented in the Supplementary Appendix. Challenges indicated by an asterisk (*) in Table 3 were suggested by validators.

Table 3. Challenges in the ODE identified from the interviews

Note. * were suggested by validators.

Challenges related to user-drivenness: Open data users must deal with different open datasets published under various standards and licenses. As highlighted by an interviewee, the EU Directive on Establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE) states that spatial data published by national mapping agencies in the EU should follow ISO standards. However, generic administrative open data are rarely published in those standards; instead, they are published in other standards (e.g., DCAT). Simultaneously, to use and possibly integrate open data from different sources for specific purposes, users must check the conditions of the relevant data licenses, and whether they are compatible. This task is not necessarily straightforward, especially for users with limited legal literacy. These technical and legal interoperability issues are exacerbated by siloed open data domains (geospatial, demographic statistics, etc.), which can be characterized as loosely connected ecosystems within the larger ODE.

Using open data may require complex technical know-how and tooling, which particularly impacts nonspecialist users (including experts on a particular domain but not others). Simultaneously, with the growing (potential) applications of open data, the diverse needs of users (e.g., in terms of the data and the format they require) are not entirely met. While some open data providers have taken the initiative to seek user feedback, limited input is obtained from nonexpert users—especially among small and medium enterprises and individual citizens.

Challenges related to circularity: Open data providers that previously sold their data lost (one of) their source(s) of income upon providing it as open data. In the EU, many organizations are legally required to publish open data even though it would not have been in line with their managerial or strategic decisions. However, open data providers receive limited value returns (particularly monetary) from the open data they provide. Meanwhile, open data use cases are not always visible. Thus, open data providers cannot fully assess the value of their open data to decide what data they (do not) need to provide and prove its value to seek (more) funding.

Challenges related to inclusivity: Nongovernment sectors (i.e., the private and civil sectors) provide limited open data, which is partly attributed to the lack of incentives to voluntarily publish open data. As noted by at least two interviewees, the legal obligation in the EU entails a major push for open data; however, this mainly affects the public sector at present. Running initiatives based on open data—as providers, users, and intermediaries—requires viable business models, which remain underdeveloped. One interviewee also noted that open data from nongovernment sectors are available in some cases but simply not visible enough. Multistakeholder engagements are necessary to encourage nongovernment sectors to contribute open data and participate in decision-making related to open data. However, individual actors face practical constraints in leading such engagements due to limited resources, time, and commitment.

Challenges related to skills: Some existing or potential open data providers have limited knowledge of the best practices for publishing open data. In the context of the EU, certain open data providers struggle to meet the requirements set by the law due to the lack of technical expertise in the organization. Conversely, potential or current open data users may have limited knowledge and skills related to using open data in a meaningful manner.

Foundational challenges: Publishing open data comes with considerable costs for providers linked to developing and maintaining the relevant infrastructure and expertise. This is especially the case for organizations that had underdeveloped data management systems before they had/decided to publish open data. In the development stage, open data providers must deal with major technical undertakings to build open data infrastructure and processes. Additionally, some open data providers are legally required to publish data in specific data models that are rather complex, such as in the case of the EU INSPIRE Directive, which was noted by at least two interviewees. Certain open data providers may also need to integrate data from different administrations before publishing it as open data, which involves significant coordination efforts. Furthermore, as the volume of open data grows, privacy concerns may become more challenging to address.

Broad challenges: Certain challenges in ODEs are an extension of broader political factors beyond open data alone, particularly surrounding policies around market competition, overarching digital strategies, and technological governance. Different governments and societies may have different preferences and approaches to these aspects, which ultimately affect the ODE. In the EU, decisions in these areas are also negotiated and made at the supranational level.

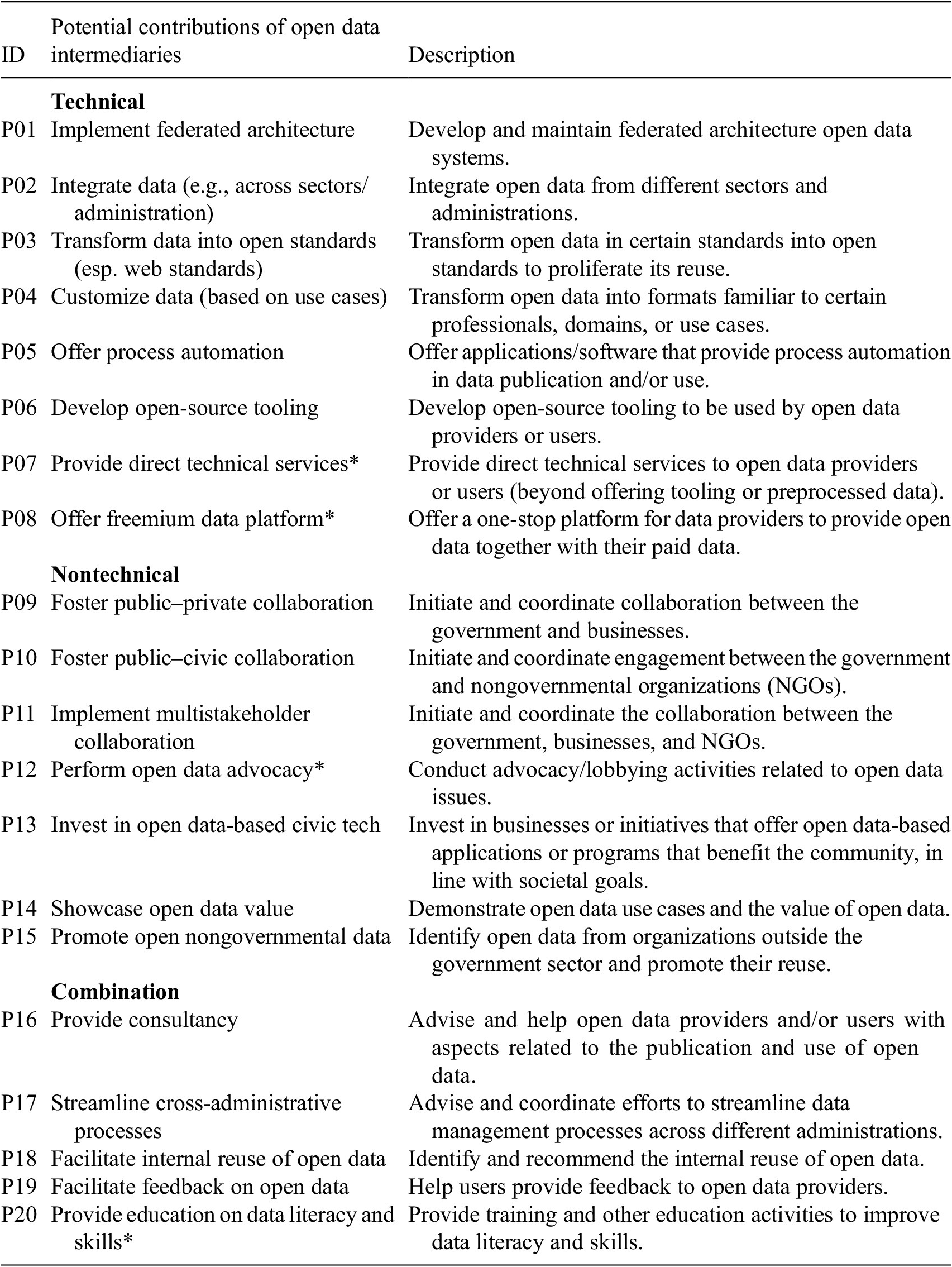

4.2. Potential contributions of open data intermediaries

Table 4 presents the potential contributions of open data intermediaries derived from the interviews. We categorized the contributions into technical, nontechnical, and combination contributions. Technical contributions may include the direct processing of open data and developing tools to facilitate its supply or use. Nontechnical contributions do not necessarily involve directly processing open data or developing tools but are more geared toward relationship building, stakeholder engagement, and financial support. Combination contributions are those that involve a mix of technical and nontechnical activities. Moreover, these potential contributions may be interrelated and some of them are not necessarily new. For instance, fostering collaborations is a known contribution of open data intermediaries, as reviewed by Shaharudin et al. (Reference Shaharudin, van Loenen and Janssen2023). However, the word “potential” refers to the potentiality of these contributions in addressing specific challenges in the ODE. Table 5 links the potential contributions of open data intermediaries with the ODE challenges they may address.

Table 4. Potential contributions of open data intermediaries

Note. * were suggested by validators.

Table 5. Potential contributions of open data intermediaries and the ODE challenges they may address

Technical contributions: By implementing federated architecture, open data intermediaries may help address user-driven challenges (different data standards, different open data licenses, and siloed open data domains) and the foundational challenges of data management systems. Integrating data may also help resolve issues of different data standards, siloed open data domains, the high technical thresholds for nonspecialist users, and unfulfilled user needs (due to fragmented data). It may also help address the limited skills of data providers and users in combining different datasets and the problem of open data being provided by heterogeneous administrations. Transforming open data into open standards, especially web standards that are already used widely across many domains, may address issues similar to integrating data. It may also help to overcome issues where data are published according to standards set by the law, but the standards are not adaptive to changing technology and user needs. Likewise, customizing data based on the common use cases in a specific industry or domain may also help to address the same problem of misaligned legal development vis-à-vis technological progress. It may also address some challenges related to skills and user-drivenness (different data standards, siloed open data domains, high technical threshold, and unfulfilled user needs) but not foundational challenges.

Open data intermediaries may also offer automation for certain open data publishing and use processes. This may help to overcome challenges around user-drivenness (siloed open data domains, high technical threshold, and unfulfilled user needs), skills, and foundational challenges (including by enhancing privacy protection). Offering open-source tooling may reduce the high technical threshold for nonspecialist users through an affordable means. This would enable the implementation of certain business models by open data actors that do not have the technical expertise and proprietary in-house tooling or financial capacity to acquire such resources. Open data intermediaries may also provide direct technical services in certain parts of open data processing (instead of providing tooling and pre-processed data). This may resolve challenges linked to the high technical threshold for using open data, limited skills among open data providers and users, and several foundational challenges (poor open data quality, technical difficulties in establishing data management systems, and complex data standards to comply with). Additionally, open data intermediaries may offer a one-stop platform for providers to offer their open data together with paid data, thereby encouraging (nongovernment) actors to provide open data through the freemium business model (addressing inclusivity challenges).

Nontechnical contributions: By fostering public–private, public–civic, and multistakeholder collaboration, open data intermediaries may help to address inclusivity, user-drivenness, circularity, and broad foundational challenges. While most links between these three contributions and their challenges are quite straightforward, the connections between public–private/multistakeholder collaborations and the challenges of development/maintenance costs incurred by the open data providers may not be very clear. The idea is that the public, private, and civil sectors may pool resources and jointly coordinate efforts to build and maintain technical infrastructure to publish open data (whether the open data are from the public, private, or civil sectors or a combination of them), thereby reducing the costs incurred for a single organization. This form of collaboration may work if all parties are interested in publishing specific open data, such as data showing the locations of electric vehicle charging stations. Open data intermediaries may facilitate this type of collaboration.

Open data intermediaries may undertake open data advocacy, among other activities, to raise awareness of the loss of open data providers’ revenue and lobby for additional funding based on the socioeconomic value of open data. Open data intermediaries may also invest in and provide business model design support to civic technology companies producing applications that reduce the technical threshold for (lay) users to benefit from open data. They may return a share of the profits to open data providers (e.g., through joint ventures) and encourage more open data releases. Furthermore, open data intermediaries may contribute to showcasing the (critical) value of open data to address circularity, inclusivity, foundational, and broad political challenges. By promoting open nongovernment data, open data intermediaries may help address most of the inclusivity challenges as well as unfulfilled user needs (user-drivenness) and the limited knowledge of (potential) open data users (skills-based).

Combination contributions: Open data intermediaries may provide various types of consultancy to open data providers and users, such as those related to technical, managerial, economic, and political aspects. The technical and managerial types of consultancy may help open data providers and users to overcome user-drivenness, skills-based, circularity, and foundational challenges. The economic and political types of consultancy may help to address the challenges faced by open data providers and users linked to requiring viable business models and mitigating broad political challenges. Open data intermediaries may also help streamline cross-administrative data management processes to tackle various issues across all dimensions, particularly foundational issues.

Open data intermediaries may facilitate the internal reuse of open data to address shortcomings of limited value return from open data, lack of incentives for publishing open data voluntarily, reliance on a political agenda, and limited knowledge of open data providers and users. For this contribution, the open data intermediary may likely be a unit within the same organization as the open data provider to have comprehensive knowledge of the data produced and used by the organization. Open data intermediaries may also facilitate feedback on open data, which may tackle some challenges across all dimensions. This facilitation of feedback may involve technical aspects (e.g., introducing a feedback feature in a data platform) or nontechnical aspects (e.g., organizing user group meetings). Additionally, open data intermediaries may provide education on data literacy and skills. Apart from tackling skills-based challenges, this education may aim to improve general public data awareness, such as on different types of data, the potential applications of open data, ethical ways of using data, and privacy aspects.

5. Discussion

This study affirms the role of open data intermediaries in addressing challenges in the ODE. Our findings show that not only could they help the ecosystem strengthen the four features of a sustainable ODE as proposed by van Loenen et al. (Reference van Loenen, Zuiderwijk, Vancauwenberghe, Lopez-Pellicer, Mulder, Alexopoulos, Magnussen, Saddiqa, de, Crompvoets, Polini, Re and Flores2021), but they could also help address foundational issues around data management systems and mitigate the broad political factors impacting ODEs. However, it is important to note that these potential contributions addressing the various challenges in ODEs would not magically materialize. To reiterate, in the ODE, actors are considered self-interested and open data intermediaries require internal incentives (e.g., through viable business models) and/or extrinsic incentives (e.g., through policies and regulations) to drive them to offer those contributions. Therefore, this study emphasizes further inquiry into the business models of open data intermediaries and other external conditions of the ODE that could encourage open data intermediaries to act in ways that support the sustainability of the ODE, in which their interests and other actors are aligned. Additionally, this study also encourages further investigations of whether some of the identified potential contributions of open data intermediaries already exist and address the ODE challenges linked to them (or others) and, if so, what the success factors are (and vice versa). Moreover, further studies could identify other potential contributions of open data intermediaries beyond those listed in this paper.

This study highlights the need to distinguish a “role” from an “actor” in the ecosystem, as elucidated by Oliveira and Lóscio (Reference Oliveira and Lóscio2018) and Shaharudin et al. (Reference Shaharudin, van Loenen and Janssen2023). Diverse ODE actors can undertake open data intermediation, including public organizations, for-profit companies, and civil society organizations. It is especially worth emphasizing that open data intermediaries do not only exist outside of the public sector, as some have implied (Balvert and van Maanen, Reference Balvert and van Maanen2019; Schrock and Shaffer, Reference Schrock and Shaffer2017). Several public organizations in our research, such as SDFI (Denmark), BKG (Germany), and IGN (France), have identified some of their tasks as being those of open data intermediaries. One of the interviewees mentioned, “We do not necessarily produce the data, but we [are] intermediaries ourselves. So we get the data from others, in particular from the official mapping agencies [redacted], and we process that data, combine it, and provide it.” Similarly, during the validation exercise, a public organization representative noted how they provide a paid service to help smaller public agencies fulfill the technical data requirements set by the law. Having said that, what a government organization can do as an open data intermediary may differ from what a for-profit company or a civil society organization can do in that role. This is due to the different legal obligations, societal expectations, resources, and other factors that these organizations have. Hence, the contributions of diverse types of open data intermediaries that are possible in practice are also different.

Our findings also suggest that an open data provider or user could benefit from the contributions of multiple open data intermediaries simultaneously, in parallel and/or sequentially. As van Schalkwyk et al. (Reference van Schalkwyk, Cañares, Chattapdhyay and Andrason2016, p. 22) argued, “No single intermediary is likely to possess all the types of capital required to unlock the full [open data] value.” This also implies that the beneficiary of an open data intermediary’s contributions could also be another open data intermediary. This insight highlights what Oliveira and Lóscio (Reference Oliveira and Lóscio2018) emphasized: value is not created in a chain but instead in a network in which actors can participate in multiple ecosystems. A chain refers to linear pathways where value is transferred from one actor to the next in a linear sequence, whereas a network refers to complex, nonlinear pathways where value is transferred from and to multiple actors in various directions. This also means that there could be multiple orderings of open data providers, intermediaries, and users in the ecosystem. Thus, apart from provider–intermediary–user relationships, they could also take the form of provider–intermediary–intermediary–user or provider–parallel intermediaries–user relationships, among others. Thus, open data intermediaries are not merely the “bridge” between open data providers and users.

Some of the challenges of the ODE identified from our interviews are very foundational issues around open data management systems or related to broader political factors and do not necessarily fit into the four features of a sustainable ODE suggested by van Loenen et al. (Reference van Loenen, Zuiderwijk, Vancauwenberghe, Lopez-Pellicer, Mulder, Alexopoulos, Magnussen, Saddiqa, de, Crompvoets, Polini, Re and Flores2021). This implies that the four features are inadequate to assess the sustainability of an ODE. Thus, additional layers of criteria may be necessary and deserve future attention. At the very least, the four features noted by van Loenen et al. (Reference van Loenen, Zuiderwijk, Vancauwenberghe, Lopez-Pellicer, Mulder, Alexopoulos, Magnussen, Saddiqa, de, Crompvoets, Polini, Re and Flores2021) must be clarified or refined to readily incorporate those foundational and broader political issues around open data. Some proposals for an ODE sustainability assessment framework have been made in the past (Vancauwenberghe, Reference Vancauwenberghe, van Loenen, Vancauwenberghe and Crompvoets2018; Welle Donker and van Loenen, Reference Welle Donker and van Loenen2017) but they were largely limited to the context of open government data and, more importantly, the object of assessment is usually the data, whereas an ODE centers the relationships between actors and the value flows instead of the data per se.

Our findings on the challenges of ODEs and the potential contributions of open data intermediaries call the boundaries of ODEs into question. Notably, the ODE challenges identified include those associated with external factors beyond just open data, and the contributions of open data intermediaries may involve many more activities than directly handling open data. Drawing from ANT, Latour (Reference Latour2007, p. 29) asserted that “it’s not the sociologist’s duty to decide in advance [emphasis added] and in the member’s stead what the social world is made of” since “social aggregates are not the object of ostensive definition—like mugs and cats and chairs that can be pointed at by the index finger—but only of a performative definition” (p. 34). Latour emphasized tracing connections “instead of being constantly bogged down in the impossible task of deciding once and for all what is the right unit of analysis” (p. 34). In other words, the boundaries of an ODE do not have to (or cannot) be defined beforehand. However, for a specific assessment, research inquiry, or intervention, one should identify relevant actors, trace their associations, and analyze their interactions, which would involve making and remaking boundaries (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Pardo and Cook2012; Lee and Hassard, Reference Lee and Hassard1999). Similarly, van Schalkwyk et al. (Reference van Schalkwyk, Chattapadhyay, Caňares and Andrason2015) argued that to determine whether an actor can be considered an open data intermediary, one should assess its “degree of agency” in fulfilling the open data intermediation function. Having said that, striking a balance between being pragmatic and reductionist is undoubtedly something that open data researchers and practitioners would have to constantly grapple with.

6. Conclusion

This paper has explored the potential contributions of open data intermediaries in addressing various challenges in ODEs. Through interviews and a validation exercise conducted with 19 individuals from 15 organizations in the EU, it has been shown that open data intermediaries could help overcome challenges that are detrimental to ODE sustainability through various technical and nontechnical contributions. For example, they may implement a federated architecture data platform, offer process automation, develop open-source tooling, invest in open data-based civic technology companies, promote open nongovernmental data, streamline cross-administrative processes, and facilitate the internal reuse of open data. This paper also demonstrated the potential efficacy of adopting the ecosystem perspective, inspired by ANT, as the analytical lens to generate insights toward improving value generation from open data.

This paper contributes to the body of knowledge on ODEs by exploring the links between the potential contributions of open data intermediaries and the challenges in ODEs. These contributions of open data intermediaries would not automatically resolve the challenges in ODEs linked to them by default; instead, they have to be designed for that purpose. As stressed in this paper, actors in ODEs are self-interested; hence, they require intrinsic incentives (e.g., through viable business models) and/or external conditions (e.g., through policies and regulations) that drive them toward acting in a particular manner. Hence, research into business models and policies relevant to open data intermediaries is necessary while considering the diverse types of actors serving the role of open data intermediaries (e.g., government organizations, companies, and civil society organizations). Notably, different types of actors would require different sets of incentives. Additionally, further research is required to investigate whether some of the contributions of open data intermediaries identified in this study already exist, address the ODE challenges linked to them (or others), and which conditions allow (or prevent) such scenarios. In conclusion, this paper paves the way for further inquiry and intervention related to open data intermediaries so that they can contribute toward sustainable ODEs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.4121/d7dd11e0-7c6c-49db-946a-ffe71520f8fd.v1.

Data availability statement

The interview guide, informed consent form template, de-identified interview transcripts, and coding results can be found in the following open repository: https://doi.org/10.4121/d7dd11e0-7c6c-49db-946a-ffe71520f8fd.v1.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the interviewees and external validators whose insights are valuable to this article. Additionally, we are indebted to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback and constructive criticism, which significantly improved the quality of this article.

Author contributions

Ashraf Shaharudin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Bastiaan van Loenen: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Marijn Janssen: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Provenance

This article is part of the Data for Policy 2024 Proceedings and was accepted in Data & Policy on the strength of the Conference’s review process.

Funding statement

This research is part of the “Towards a Sustainable Open Data ECOsystem” (ODECO) project. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 955569. The opinions expressed in this document reflect only the author’s view and in no way reflect the European Commission’s opinions. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Competing interest

None of the authors declare a conflict of interest in relation to the research conducted for this article.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.