1 Overview

Over the years, the economic relationship between China and African states has continued to grow and this is evident in the volume of Chinese investments in Africa.Footnote 1 In the wake of these investments, China and African states have signed bilateral investment treaties (BITs), which aim to promote the development of host states and protect foreign investments from one contracting state in the territory of the other contracting state, thereby stimulating foreign investments by reducing political risk. BITs are unique in character in that they provide substantive protections to foreign investors and a basis for claims by an individual or company against a host state on grounds that such substantive protections have been breached by the host state. In order to avoid the need to turn to the national courts in the host state for a judicial remedy, BITs usually contain an arbitration clause submitting disputes to a neutral arbitration tribunal. This case study demonstrates one such instance where, in a first-of-its-kind case, a Chinese investor sued Nigeria, an African host state, for breach of its treaty obligations under the China-Nigeria BIT 2001 (“China-Nigeria BIT”),Footnote 2 and throws light on how BITs can be used in the protection of Chinese outbound investments, including in Africa.

2 Introduction

This case study discusses an investment dispute between a Chinese company, Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Company Limited (“Zhongshan”), and the Federal Republic of Nigeria (“Nigeria”) under the China-Nigeria BIT that resulted in an arbitration award dated 26 March 2021 (the “Award”).Footnote 3 This is the first investment treaty arbitration won by an investor from Mainland China against a sovereign state in Africa. It is also the first arbitration Award ever made against Nigeria in an investment treaty dispute. The place of arbitration was London, United Kingdom, but the arbitration proceedings were held virtually due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. The hearing was conducted under the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL).Footnote 4

This case study sheds light on Chinese corporate behavior, Chinese companies’ approaches to mitigating investment risks in international business, their use of the investment treaty arbitration regime,Footnote 5 and, ultimately, Chinese investment behavior at large. The case study demonstrates how Chinese companies navigate policy and regulatory challenges in local markets in their host states. The case of Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd. v. Federal Republic of Nigeria is a good example of the use of an investment treaty by a Chinese investor to protect its investment against the unbridled use of power by a sovereign host state, in this case Nigeria. In terms of data and methodology, the case study draws on primary source documents (see Table 6.3.1) and a semi-structured interview with one of the lawyers who indirectly participated in the arbitration proceedings. The interview revealed that this case study should reassure other Chinese companies that recourse to investment treaty arbitration may increase protection for their foreign investment. This case, therefore, serves as a valuable lens through which to examine Chinese investments in Nigeria, and on the African continent at large.

Table 6.3.1 List of primary documents

| Primary documents | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Annual flow of foreign direct investments from China to Nigeria between 2011 and 2021 |

| 2. | Map of Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone |

| 3. | Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria for the Reciprocal Promotion and Protection of Investments (China-Nigeria BIT), 2001 |

| 4. | Framework Agreement between Zhuhai and Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone (“OGFTZ Company”) on the Establishment of Fucheng Industrial Park in Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone, 2010 |

| 5. | Joint Venture Agreement between Ogun State, Zhongfu and Zenith Global Merchant Limited for the Development, Management, and Operation of the Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone, 2013 |

| 6. | Framework Agreement between Ogun State, Zhongfu and Zenith Global Merchant Limited, and Xi’an Ogun Construction and Development Limited Company, 2016 |

| 7. | Final Arbitral Award dated 26 March 2021 in Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd. v. Federal Republic of Nigeria |

| 8. | Order of Seizure of Nigeria’s Bombardier Aircraft Issued by the Superior Court of Quebec, Canada, 25 January 2023 |

| 9. | Entrustment of Equity Management Agreement between Guangdong Xinguang International Group Co., Ltd., and Zhuhai Zhongfu Industrial Group Co., Ltd., 2012 |

| 10. | Petition Filed by Zhongshan to Recognize and Enforce Foreign Arbitral Award Between Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd. v. The Federal Republic of Nigeria before the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (Case 1:22-cv-00170), Civil Action, 25 January 2022 |

| 11. | An Order of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia Recognizing the Arbitral Award Between Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd., v. Federal Republic of Nigeria [Civil Action No. 22-170 (BAH)], 26 January 2023 |

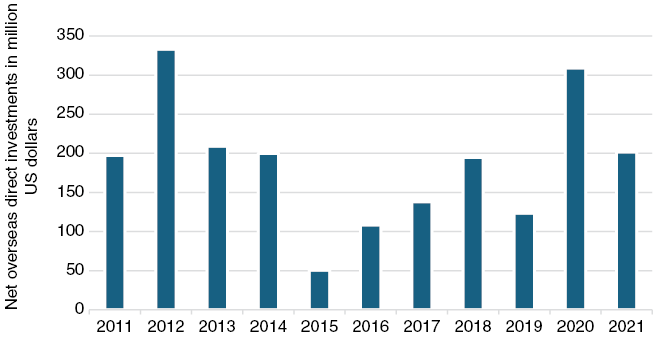

As background to the China–Nigeria investment relationship, China’s outbound investments across the world, including in African countries, have continued to grow massively since 2005, now exceeding US$2.3 trillion.Footnote 6 In Africa and Nigeria specifically, Chinese investments are rooted in various institutional and policy frameworks adopted by China and African countries. Since the beginning of the century, Chinese state-owned enterprises and private companies have increasingly invested in Nigeria under China’s investment policy framework known as the “Going Out” strategy.Footnote 7 The result has been an influx of Chinese businesses into the Nigerian market. Figure 6.3.1 shows the volume of foreign direct investment from China to Nigeria between 2011 and 2021. As the data shows, about US$201.67 million’s worth of direct investments from China were made in Nigeria in 2021. Chinese investment in Nigeria’s manufacturing sector can be traced back to as early as the 1960s when private Chinese companies, such as the Lee Group of Companies and Western Metal Products Company, made early strides in Nigeria.Footnote 8

Figure 6.3.1 Annual flow of foreign direct investments from China to Nigeria between 2011 and 2021 (million US$)

In addition to the “Going Out” strategy, the first Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Summit was held in Beijing in November 2006 where a new type of strategic partnership between China and African states was declared.Footnote 9 The African continent has great potential to attract Chinese investors, particularly given that Africa features natural resources and emerging economies.Footnote 10 At the Summit, the Chinese and African governments agreed to establish special economic zones, among other things, to deepen economic and trade relations between China and African states.Footnote 11 In fact, the Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone (the “Zone”),Footnote 12 which is the location of the Chinese investment that resulted in the investment arbitration that this case study discusses, was established in 2009 and exemplifies the implementation of one of the declarations of the 2006 FOCAC Summit and the Sino-Nigeria investment partnership. The Zone is located in Ogun State in Southwest Nigeria,Footnote 13 and 50 km from Lagos as shown in Figure 6.3.2.Footnote 14 The Zone covers an area of 2,000 ha of land owned by the Ogun State government.Footnote 15 For Nigeria, the establishment of the Zone is economically significant as the objective is to support the country’s plan to diversify its economy away from sole reliance on petroleum. As of September 2023, there are 56 companies operating in the Zone and 600 Chinese employees.Footnote 16 The Zone is also seen by Chinese authorities as a necessary component of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) adopted by the Chinese government in 2013.

Figure 6.3.2 Map of Ogun Guangdong free trade zone

As a general observation, cross-border investments by Chinese companies in emerging markets are sometimes prone to risks, which include adverse or illegitimate actions from the host state. To guard against the attendant risks, China signs investment treaties with foreign states. As of the end of 2023, the Chinese government has 107 BITs with foreign states (including Nigeria) that are in force and 16 BITs that have been signed but are not yet in force.Footnote 17 These BITs primarily aim to protect Chinese investors and their investments in the host state, while host states hope that such investments will foster overall socioeconomic development in their country. Therefore, the BITs that China has signed and are in force typically provide substantial protection and guarantees for qualifying Chinese investments abroad. In these BITs, Nigeria, for instance, guarantees Chinese investors that their investments shall be treated in a fair and equitable manner and shall not be expropriated without appropriate compensation. In addition, the BITs, as this case study will demonstrate, allow Chinese investors to institute claims against host states before an arbitral tribunal if their investments are treated in a manner that is contrary to the terms of the relevant BIT, without the need to exclusively rely on the national courts of the host states. In recent times, Chinese business enterprises have demonstrated their willingness to resort to arbitration to resolve investment disputes between them and host states for the protection of their investments abroad. According to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) case database, as of 10 September 2023, there have been ten ICSID cases filed by Chinese investors as claimants, of which five cases are still in progress.Footnote 18

The case of Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd. v. Federal Republic of Nigeria is an example of an investment treaty claim brought by a Chinese investor against a host state on the basis that Nigeria (through the Ogun State government in Southwest Nigeria and other government agencies in Nigeria) violated the provisions of the China-Nigeria BIT by taking measures that wrongfully affected the Chinese investments. Specifically, the claim concerns the wrongful termination of Joint Venture Agreements (JVAs) for the development and operation of the Fucheng Industrial Park within the Zone.

This case study contributes to the growing literature on Sino-African investment relations and international investment arbitration more generally. It is divided into five broad sections. Following the overview of this chapter discussed in Section 1 above and this introductory part set out in Section 2, in Section 3 we set out the facts of the investment dispute. In this section, we describe the relationship between the parties to the dispute, the issues in dispute between them, and the character of the arbitration and Nigerian court proceedings arising out of the dispute. We further discuss the various strategies adopted by Zhongshan to mitigate the investment risks it faced in Nigeria. In addition, we also discuss Zhongshan’s claims against Nigeria in the arbitration proceedings and Nigeria’s responses to those claims, before setting out the result of the arbitration proceedings. In Section 4, we provide concluding remarks on the case study, and in Section 5 provide some discussion questions and comments.

3 The Case

This section sets out a high-level summary of the facts that led to the dispute where Zhongshan (the “Claimant”) alleged that the actions of persons and entities attributable to Nigeria under international law deprived Zhongshan of its substantial investments in Nigeria, contrary to the provisions of the China-Nigeria BIT 2001.Footnote 19

3.1 The Relationship between the Parties

The subject of this dispute is the Zone. The Zone was governed by a JVA signed on 28 June 2007 (the “2007 JVA”) by the Ogun State government, China-Africa Investment Limited, Guangdong Xinguang International Group, and CCNC Group Limited. Under the provisions of the 2007 JVA, the development of the Zone was to be carried out through the Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone Company (“OGFTZ Company”), a subsidiary of the Ogun State government, which was to be jointly owned for ninety-nine years by a consortium of three entities: the Ogun State government, China-Africa Investment Limited, and CCNC Group Limited.Footnote 20

Early in the course of the project, China-Africa Investment Limited (a Chinese business enterprise) experienced financial problems and the development of the Zone was abysmally slow. The financial situation of China-Africa Investment Limited led to another Chinese company, Zhuhai (the parent company of Zhongshan), taking over the development and management of the Zone.Footnote 21 On 24 January 2011, the Claimant incorporated its local Nigerian entity, Zhongfu International Investment FZE (“Zhongfu”), to manage its investments in Nigeria on its behalf. Zhongfu was consequently registered as a Free Trade Zone Enterprise in the Zone.Footnote 22 On 10 April 2012, the Ogun State government confirmed the appointment of Zhongfu as the manager and operator of the Zone, after terminating the involvement of China-Africa Investment Limited.Footnote 23 Consequently, the Ogun State government, Zhongfu, and Zenith Global Merchant Limited (“Zenith”) entered into a JVA for the development, management, and operation of the Zone on 28 September 2013 (the “2013 JVA”).Footnote 24 Under Clause 3 of the 2013 JVA, OGFTZ Company was appointed as the joint venture company, and ownership of OGFTZ Company was divided as follows: 60% to Zhongfu and 20% each to Ogun State and Zenith.Footnote 25 Clause 27 of the 2013 JVA also provides that any dispute arising from the 2013 JVA would first be settled by amicable discussions between the parties, failing which either party could refer the dispute to the Singapore International Arbitration Centre for arbitration under the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules.Footnote 26

3.2 The Dispute between the Parties

Zhongfu maintained that it has, since 2010, developed and managed the Zone while marketing it to potential occupiers. Specifically, it has improved communication systems, upgraded the roads, erected a perimeter fence, and opened a bank, a supermarket, a hospital, and a hotel to assist potential occupiers in the Zone.Footnote 27

Between April and August 2016 (the “2016 Actions”), Ogun State purported to terminate Zhongfu’s appointment as manager of the Zone and attempted to install a new manager immediately. This was, however, preceded by some key events. First, 51% of the shares of China-Africa Investment Limited were acquired by a Chinese company, New South Group (NSG), the notice of which the Chinese Consulate in Nigeria gave to the Ogun State government.Footnote 28 Ogun State interpreted this as meaning that Zhongfu’s management rights of the Zone would be transferred to NSG.Footnote 29 Second, Ogun State reacted by writing to Zhongfu, accusing it of fraud and misrepresentation of facts, demanding that the Zone be handed to Zenith within thirty days.Footnote 30 Zhongfu rebuffed Ogun State’s claims as erroneous,Footnote 31 and Ogun State started taking actions aimed at driving Zhongfu out of Nigeria.

Under direction of the Ogun State government, the police harassed Zhongfu’s workers, who were threatened with prosecution and prison sentences in order to get them to vacate the Zone.Footnote 32 The chief financial officer (CFO) of the Zone, Mr. Wenxiao Zhao, was arrested, beaten, detained, and starved of food and water for ten days by the police.Footnote 33 The CFO’s travel document was also seized by the Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS) to prevent him from leaving Nigeria. The CFO was later released on bail and his travel document was returned to him, enabling him to leave Nigeria, albeit hurriedly. Furthermore, the NIS seized the immigration papers of Zhongfu’s other expatriate staff so that none of them would be able to work in Nigeria.Footnote 34

Ultimately, Zhongfu’s principal officers left Nigeria in October 2016.Footnote 35 The departure’s proximate cause was the police harassment but there were underlying and aggravating issues as well. Chinese staff struggled with the Nigerian business environment, cultural differences, and the English language. That Zhongshan’s investment was located in a community that is somewhat remote from the center of commerce and in a non-cosmopolitan location may be a plausible explanation for the language and cultural barriers.

What did Zhongfu do to warrant these treatments from Nigeria? As we will show in the following sections, Nigeria accused Zhongfu of misrepresentation and concealment of material facts that, if the Ogun State government had been aware, would have meant it would not have entered into the 2013 JVA. We will discuss how Zhongfu set out to mitigate this challenge.

3.3 Nigeria-Related Court Proceedings Commenced by Zhongfu

Further to the foregoing dispute, Zhongfu commenced an action on 18 August 2016 at the Nigerian Federal High Court in Abuja (the “Zhongfu FHC Action”) against the Nigeria Export Processing Zones Authority (NEPZA), the Attorney-General of Ogun State, and Zenith, seeking declaratory and injunctive reliefs that Zhongfu is the manager of the Zone. The Zhongfu FHC Action alleged breaches of Zhongfu’s contractual rights as a manager of the Zone and Zhongfu’s tenancy rights under the 2010 Framework Agreement.Footnote 36 On 9 September 2016, Zhongfu brought another suit at the Ogun State High Court against OGFTZ Company, the Ogun State government, and the Attorney-General of Ogun State, seeking possession of the Zone, injunctive reliefs, damages of US$1,000,797,000, and interest (the “Zhongfu SHC Action”). Zhongfu’s claim in the Zhongfu SHC Action was primarily based on its right of possession under the 2010 Framework Agreement.Footnote 37

On the same day, the CFO instituted proceedings at the Nigerian Federal High Court in Abuja against the Nigerian Police Force, the Inspector-General of Police, the Commissioner of Police for the Federal Capital Territory, and others for damages for his mistreatment (“Mr. Zhao Action”).Footnote 38 All three court actions were discontinued in early 2018 as a result of the refusal of the defendants to comply with the timelines for filing court documents, among other procedures.Footnote 39

In the meantime, and in a bid to enforce its contractual rights, Zhongfu commenced commercial arbitration proceedings against the Ogun State government and Zenith at the Singapore International Arbitration Centre, pursuant to Clause 27 of the 2013 JVA.Footnote 40 However, Zenith sought and obtained an anti-arbitration injunction against Zhongfu on 29 March 2017 on the basis that Nigeria, not Singapore, was supposed to be the seat of arbitration and the Zhongfu FHC Action constituted a waiver of Zhongfu’s right to arbitrate (or rendered the arbitration abusive or oppressive).Footnote 41 Zhongfu appealed this order, but the appeal, as noted, was discontinued before the instant investment treaty arbitration was formally commenced by the Claimant (Zhongshan, the parent company of Zhongfu) against Nigeria under the China-Nigeria BIT.Footnote 42

3.4 Zhongshan’s Strategies for Mitigation

In terms of their projects in Africa, Chinese investors may be open to negotiation and amicable settlement, as well as the exhaustion of local remedies available in a host state (i.e., including litigation proceedings in domestic courts).Footnote 43 Zhongshan employed four strategies for mitigating the investment risk and local challenges it was experiencing in Nigeria. First, and as described in the previous section and in Table 6.3.2, Zhongfu instituted legal actions in the Nigerian courts against (i) the Attorney-General of Ogun State and Zenith for breach of contractual and tenancy rights and (ii) the Ogun State government and the Attorney-General of Ogun State, seeking an order of possession, injunctive reliefs, damages, and interest. In addition, Mr. Zhao, the CFO of the Zone, instituted a legal action in the Nigerian courts against the Nigerian Police Force, the Inspector-General of Police, and the Commissioner of Police for the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, seeking to protect his fundamental rights.Footnote 44 Separate from the legal actions instituted in the Nigerian courts, Zhongfu also commenced commercial arbitration proceedings against the Ogun State government and Zenith under the 2013 JVA.

Table 6.3.2 Summary table of cases

| Date | Parties | Court/location | Nature of dispute | Order(s) sought | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 August 2016 | Zhongfu v. Nigeria Export Processing Zone Authority (NEPZA), Attorney-General of Ogun State, and Zenith Global Merchant Limited | Federal High Court, Abuja, Nigeria | Allegations of breaches of Zhongfu’s contractual and tenancy rights | A declaration that Zhongfu is the manager of the Zone and a reinstatement of the company’s management rights in the Zone | Discontinued |

| 2 | 9 September 2016 | Zhongfu v. OGFTZ Company, Ogun State government, and Attorney-General of Ogun State | Ogun State High Court, Nigeria | Zhongfu’s right of possession | Reinstatement of Zhongfu’s possession rights of the Zone, injunctive reliefs, damages of US$ 1,000,797,000 billion, and interest | Discontinued |

| 3 | 9 September 2016 | Mr. Wenxiao Zhao v. Nigerian Police Force, the Inspector-General of Police, the Commissioner of Police for the Federal Capital Territory | Federal High Court, Abuja, Nigeria | Physical maltreatment of Mr. Zhao by the Nigerian Police | Damages | Discontinued |

| 4 | 2017 | Zhongfu v. Ogun State government and Zenith | Singapore International Arbitration Centre | Allegations of breach of contract | Payment of restitution | Not concluded (please see the reason in item 5) |

| 5 | 5 January 2017 | Zenith v. Zhongfu | Ogun State High Court, Nigeria | An anti-suit injunction concerning the Singapore arbitration | An order restraining Zhongfu from proceeding with the arbitration in Singapore | A permanent restraining order was granted |

| 6 | 23 June 2017 | Zhongfu v. Zenith | Court of Appeal, Lagos, Nigeria | To set aside the order by the Ogun State High Court | Sought an order to quash the restraining order granted by Ogun State High Court | Discontinued |

| 7 | 30 August 2018 | Zhongshan v. Federal Republic of Nigeria | London, United Kingdom | Breach of Nigeria’s obligations under the China-Nigeria BIT | Compensation, interest, and costs | Award issued |

When it appeared that the Nigerian litigation proceedings and the commercial arbitration proceedings could not move forward, on 21 September 2017 Zhongshan sent a notice of dispute and request for negotiations to Nigeria (the “2017 Notice”), in which it expressed its willingness to discuss the dispute that had arisen as a result of the Ogun State government’s purported termination of Zhongfu rights in the Zone and the allegations and counter-allegations by the parties between April and August 2016.Footnote 45 This request was made further to Article 9(3) of the China-Nigeria BIT, which provides that if “a dispute cannot be settled within six months after resort to negotiations … it may be submitted at the request of either Party to an ad hoc tribunal.” However, no response was received from Nigeria. Consequently, Zhongshan served a request for arbitration pursuant to Article 9 of the China-Nigeria BIT, which marked the commencement of the investment treaty arbitration that resulted in the Award. The next section sets out the arguments of the parties to the investment treaty arbitration.

3.5 Arbitration

The arbitration tribunal was formally constituted on 5 January 2018 following the appointment of the arbitrators in accordance with Article 9(4) of the China-Nigeria BIT. Zhongshan filed its statement of claim, witnesses’ statements, and expert evidence from an accountant on the quantum of compensation.Footnote 46 Nigeria responded with its Statement of Defense and witness statements. Through a preliminary application, Nigeria also requested the tribunal to bifurcate (divide) the proceedings and determine the law that should govern the dispute. After Zhongshan’s response to the bifurcation of the proceedings and the question of the applicable law, the tribunal declined to bifurcate the proceedings. The tribunal ruled that the applicable law to the dispute was an amalgam of Nigerian law, the provisions of the China-Nigeria BIT, and the generally recognized principles of international law. Notably, Nigeria was uncooperative in the production of any documents requested by Zhongshan and ordered by the tribunal.Footnote 47

3.5.1 Zhongshan’s Claims against Nigeria

Zhongshan claimed that Nigeria breached Articles 2, 3, and 4 of the China-Nigeria BIT between April and August 2016 by seizing its assets and depriving it of a substantial investment in the Zone. Specifically, Zhongshan made five interrelated claims against Nigeria. First, Zhongshan claimed that Nigeria breached its obligation of fair and equitable treatment of Chinese investors under Article 3(1) of the China-Nigeria BIT.Footnote 48 Second, Zhongshan claimed that Nigeria unreasonably discriminated against it and therefore breached Article 2(3) of the BIT.Footnote 49

Third, it claimed that Nigeria failed to provide the “continuous and full protection and security” afforded by Article 2(2).Footnote 50 Fourth, Zhongshan claimed that Nigeria violated its contract with the petitioner and thus breached Article 10(2). Fifth, Zhongshan claimed Nigeria wrongfully expropriated its investments without compensation, in breach of Article 4.Footnote 51 Zhongshan claimed US$1,446 million.

Under the China-Nigeria BIT, Chinese businesses in Nigeria are protected from nationalization or expropriation unless the expropriation is in the public interest, the expropriation was done in accordance with domestic legal procedure, and it was done without discrimination.Footnote 52 Chinese investors are entitled to fair compensation if their investments are expropriated. Fair compensation is the value of the expropriated investments immediately before the expropriation is proclaimed. The basis or standard of assessment of compensation in this type of case (a breach of the China-Nigeria investment treaty) is full reparation for Zhongshan’s losses. Consequently, Zhongshan relied on Article 9 of the China-Nigeria BIT to ask the arbitration tribunal to order Nigeria to compensate it for the wrongful activities of its government agencies and for the losses it incurred as a result of the breach.

3.5.2 Nigeria’s Responses to Zhongshan’s Claims

Developing states now pay attention to investment arbitration given the financial implications of losing a legal dispute of that nature. Although Nigeria agreed to and participated in the arbitration, it made some jurisdictional and preliminary objections before the tribunal by arguing that the arbitral tribunal had no jurisdiction over the dispute based on the following grounds. First, Nigeria contended that Zhongshan’s claims had to do with the conduct of a constituent state in Nigeria and not the conduct of Nigeria (except the legal actions at Nigeria’s federal court) as a sovereign state and therefore there is no valid claim against Nigeria in international law.Footnote 53 As we will elaborate in Section 5.1, the tribunal relied on customary international law to attribute the conduct of the Ogun State government, a constituent state in Nigeria, to a sovereign state, Nigeria. Second, Nigeria argued that Zhongshan did not hold an “investment” within the meaning of Article 1(1) of the BIT.Footnote 54 Nigeria’s argument here is on the basis that Zhongfu, and not Zhongshan, is the investor. As we have noted, Zhongshan invested in Nigeria through its subsidiary, Zhongfu, to comply with the requirements of Nigerian Company Law. Third, Nigeria challenged the jurisdiction of the tribunal to arbitrate the investment dispute on the basis that Zhongshan did not wait for the six-month period referred to in Article 9(3) of the China-Nigeria BIT to expire before it went to arbitration.Footnote 55 Fourth, Nigeria asked the tribunal to invoke “the fork-in-the-road” clause contained in Article 9(3) of the China-Nigeria BIT to the effect that the tribunal has no jurisdiction because the Nigerian court proceedings operated as a bar to the arbitration.Footnote 56 Nigeria argued that the Nigerian court proceedings initiated by Zhongfu amounted to the submission of the “dispute to a competent court” in Nigeria within the meaning of the BIT. Fifth, Nigeria argued that Zhongshan’s claim should not be adjudicated in the absence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) government being involved in the arbitration. Lastly, Nigeria posited that as long as Zhongshan was basing its claim on the Nigerian court proceedings and/or the anti-arbitration injunction, it cannot do so because it failed to appeal the court order.Footnote 57

3.6 Result of Arbitration

Drawing on customary international law, the tribunal rejected Nigeria’s argument that Zhongshan has no valid claim against Nigeria. The tribunal relied on Articles 1, 4.1, 9.2, and 5, respectively, of the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (2001), adopted by the International Law Commission,Footnote 58 to hold that all organs of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, including those that have independent existence under Nigerian law such as the Ogun State government, are to be treated as part of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The tribunal found that the parties to the 2013 JVA intended that the Ogun State government would strictly observe the terms of the China-Nigeria BIT, which is a strong indication that Ogun State would be subject to the conditions of the BIT. According to the tribunal, investment treaties would be almost meaningless if they did not apply to actions of local, as opposed to national, government. Therefore, it did not matter that Zhongshan’s case was primarily based on the actions of the Ogun State government.Footnote 59

On Nigeria’s second argument against Zhongshan’s claim, the tribunal was not persuaded by Nigeria’s argument that Zhongshan had no investment in Nigeria. The tribunal reasoned that Zhongshan invested in Nigeria through a corporate vehicle (subsidiary), Zhongfu, by paying money to acquire the investment and incorporating Zhongfu to undertake the day-to-day responsibilities arising from the investment.Footnote 60 The tribunal dismissed Nigeria’s third argument that it did not have jurisdiction over the case as Zhongshan did not wait for the expiration of the six-month period required by the China-Nigeria BIT before filing its arbitration claim. As we noted in Section 3.1, Zhongshan notified Nigeria of its intention to negotiate and settle the dispute through a letter in September 2017, but Nigeria did not respond to the offer. The tribunal, therefore, dismissed Nigeria’s argument on the basis that the facts contradicted Nigeria’s position as it neither acknowledged the receipt of the 2017 letter nor negotiated with Zhongshan.Footnote 61

Furthermore, the tribunal rejected Nigeria’s fork-in-the-road argument because neither Zhongshan nor Nigeria, as a sovereign state, was a party at any of the domestic court proceedings (the parties were, at all times, Zhongfu, NEPZA, the Attorney-General of Ogun State, and Zenith). Nigeria’s fork-in-the-road argument also failed because the tribunal distinguished the characters and particularities of the Nigerian proceedings from those of the arbitration. Zhongfu’s SHC Action was based on alleged breaches of its contractual and possessory rights under the 2010 Framework Agreement and the 2013 JVA, and Zhongfu’s FHC action, on alleged breaches of Nigerian domestic public law, whereas Zhongshan’s case in this arbitration is based entirely on the China-Nigeria BIT.

In both the state and federal court actions, Zhongfu, as Table 6.3.2 shows, sought declaratory and injunctive reliefs, whereas in this arbitration Zhongshan sought compensation. The Nigerian court cases are similar to the arbitration only to the extent that Zhongfu also sought damages.Footnote 62 Concerning Nigeria’s argument that the PRC has to be present before the tribunal to explain the rationale behind Note 1601, the tribunal held that the official representation through Note 1601 from the PRC is irrelevant to Zhongshan’s claim as it does not need to rely on the Note to prove the existence of Zhongfu’s rights in Nigerian law as a result of entering into the 2010 Framework Agreement and the 2013 JVA, the deprivation of those rights by the statements and actions of various organs of the Nigerian state, and that the deprivation was a breach of Nigeria’s obligations under the BIT.Footnote 63 The tribunal reasoned that, if Nigeria wanted, it could have called one of the senior employees of the PRC to testify in the arbitration, but it failed to do so. The tribunal also held that the Nigerian court proceedings and anti-suit injunction did not amount to a breach of the China-Nigeria BIT.Footnote 64

In rendering its Award, the tribunal found that the 2016 Actions of Ogun State, NEPZA, and Nigerian Police breached Zhongshan’s rights under Articles 2(3), 3(1), and 4 of the China-Nigeria BIT.Footnote 65 The reason for this finding is that Zhongfu’s interest in the Zone was entitled to continuous protection.Footnote 66 The tribunal determined that the 2016 Actions by Nigerian state actors deprived Zhongfu of its rights under the 2010 Framework Agreement and the 2013 JVA. The tribunal held that the failure of Nigeria’s court to restrain the agencies of the host government or to declare their use of state power illegitimate complicated and exacerbated the illegitimacy of the 2016 Actions. The tribunal noted that Zhongfu was doing a good job that had been recognized publicly by the Nigerian Customs Service and in a video by the Economist Intelligence Unit,Footnote 67 and what is more, the Zone had begun to generate considerable tax revenue for the Nigerian government.Footnote 68 The tribunal ordered Nigeria to pay Zhongshan the amounts as follows:

1. compensation for the expropriation in the sum of US$55.6 million;

2. moral damages in the sum of US$75,000, representing around US$5,000 for each day of Mr. Zhao’s mistreatment plus a further sum to reflect the other inappropriate behavior of representatives of Nigeria toward employees and a director of Zhongfu;

3. interest on the aforesaid two sums from 22 July 2016 at the one-month USD LIBOR rate plus 2% for each year, or proportion thereof, such interest to be compounded monthly, until and including the date of the award, in the sum of US$9.4 million;

4. in respect of the Claimant’s legal and related costs of the arbitration, the sum of £2,509,789.57;

5. £354,655.17 in respect of the other costs of the arbitration;

6. post-Award interest on the sums specified on all the amounts specified in sub-paragraphs 52(a)–(c) above from the day after the Award until payment. The Award stipulated that this post-Award interest should be calculated at the one month USD LIBOR rate plus 2% for each year, or proportion thereof, such interest to be compounded monthly, until and including the date of payment (and should, for any reason, USD LIBOR cease to be operative while any amount remains outstanding, the interest due shall from that date onward be calculated on the basis of whatever rate is generally considered equivalent to USD LIBOR plus 2%, compounded monthly, until and including the date of payment);Footnote 69 and

7. post-Award interest on the sums specified on all the amounts specified in sub-paragraphs 52(d)–(e) above from the day after the Award until payment. The compensation, moral damages, and interests are to be paid in US dollars while the legal fees and costs related to the arbitration are in British pounds.

Investment treaties have a force of law that can affect the economy of a sovereign nation.Footnote 70 International investment arbitration students and lawyers need to be pragmatic because of the quantum of award as in this case study.Footnote 71 As of the time of writing, Nigeria has not paid the amounts of money awarded against it by the tribunal. A party that received a favorable award in an investment arbitration needs to take procedural steps to enforce the award and reap its benefits. In this connection, on 8 December 2021, Zhongshan filed an enforcement action in an English High Court.

In response, Nigeria challenged Zhongshan’s legal action to enforce the Award under the English Arbitration Act,Footnote 72 on the basis that the tribunal lacked jurisdiction, but the English court issued an order that recognized the tribunal’s Award on 21 December 2021.Footnote 73 Nigeria further relied on the UK State Immunity Act of 1978 to plead sovereign immunity from the enforcement of the Award before an English Court of Appeal.Footnote 74 However, it was late in filing the application as it had seventy-four days from the date of the English High Court’s order to apply to the Court of Appeal to set aside the order. Nigeria, therefore, sought an extension of time to apply and leave (i.e., permission) from the English Court of Appeal to set aside the order of the High Court that ordered the enforcement of the Award.

On 20 July 2023, the Court of Appeal declined to grant the extension and leave primarily on the basis that there was no likelihood that the appeal would be successful. Similarly, Zhongshan has also filed a legal action before the US District Court for the District of Columbia on 26 January 2023 asking the court to recognize the Award and order for its enforcement against Nigeria.Footnote 75 Here, Nigeria has unsuccessfully challenged the enforcement of the Award chiefly on the legal basis that the arbitral tribunal did not have jurisdiction to hear the arbitration and that the dispute was not governed by the New York Convention.Footnote 76 It is important to explain that, traditionally, the New York Convention governs the enforcement of commercial arbitration awards and does not apply to investor–state arbitration, which is usually governed by the ICSID and other treaties. However, the US courts have regularly confirmed arbitral awards rendered under investor–state arbitration in which sovereign nations have been found to breach treaty, rather than contractual obligations, holding that investment treaty arbitration qualifies as commercial for the purpose of recognition and enforcement under the New York Convention.Footnote 77 In furtherance of its efforts to enforce the Award, Zhongshan has begun to seize Nigeria’s assets. Zhongshan obtained an order from a Superior Court, sitting in Montreal, Quebec, Canada on 25 January 2023 to seize a Bombardier 6000 Jet belonging to Nigeria, all rights of Nigeria in the aircraft, any proceeds from the sale of the aircraft that is payable or belonging to Nigeria, and the aircraft’s logbook.Footnote 78

4 Conclusion

As China–Nigeria investment relations continue to grow, this case study demonstrates that international investment disputes are bound to arise from such engagements because of foreign parties, different regulatory regimes, the ownership structure of the investment, issues of state sovereignty, and cultural differences, to mention only a few contentious issues. What is more, investor-state arbitration is becoming a popular mechanism for the settlement of foreign investment disputes, even though the investment arbitration model is currently facing a backlash.Footnote 79

To elaborate, investment arbitrations are widely touted to be faster, guarantee the privacy of the parties, and tend to preserve the investment relations of the disputing parties in comparison with litigation in conventional law courts. However, the arbitration industry has been implicated in perpetuating an investment regime that prioritizes the rights of investors, particularly those from the West, at the expense of democratically elected national governments and sovereign states, especially those in the developing world.Footnote 80 There are concerns in the literature that the arbitration sector has built a multimillion-dollar, self-serving industry, dominated by a narrow exclusive elite of law firms and lawyers whose interconnectedness and multiple financial interests raise serious concerns about their commitment to delivering fair and independent judgments.Footnote 81 According to Corporate Europe Observatory and the Transnational Institute, the arbitration industry has become big business for arbitrators and lawyers as they profit handsomely from arbitration awards against sovereign states.Footnote 82 Critics claim that the neutrality of arbitral institutions is illusory because arbitrators play highly active roles in arbitration proceedings, and many of them have strong personal and commercial ties to transnational companies.Footnote 83 According to our interview participant, the China-Nigeria BIT is an old-generation treaty that is due for renegotiation to reflect modern developments in cross-border investment, and thus its out-of-datedness may reflect some of these larger concerns.

These critiques of the international arbitration system are important and contribute to the ongoing reform of the international arbitration system. In the meantime, this case study demonstrates how non-Western foreign investors can protect their investments under BITs. Regardless of its out-of-datedness, the China-Nigeria BIT (as well as the Nigerian Investment Promotion Commission Act), provides substantive protections for foreign investments. The protections guarantee that every investment (either by Chinese companies in Nigeria or by Nigerian companies in China) will be treated fairly and equitably and the foreign investment will not be expropriated without a fair compensation to the affected party.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

The Chinese government has increasingly demonstrated its commitment to the protection of the investments of its nationals in foreign countries as evident in the more than 100 BITs it has signed with other sovereign states. Before the commencement of the investment arbitration that we have discussed in this case study, there were a variety of domestic court cases that were mostly instituted by Zhongfu and Mr. Wenxiao Zhao against the agents of the Nigerian state and substate actors to protect Zhongfu’s investment and the company’s management from arbitrary expropriation and harassment by the local police. In a jurisdiction such as Nigeria, which is yet to attain judicial independence from the executive arm of government, the reality of obtaining justice through a fair and transparent process may be difficult for a foreign investor, particularly when its economic interests are in direct conflict with those of their host state.

The China-Nigeria BIT played a decisive role in the protection and realization of the investment rights of Zhongshan (from the stage of obtaining a favorable arbitral award to the enforcement stage – seizing the assets of Nigeria in Canada). International investment jurisprudence,Footnote 84 customary international law, and the language or wording of the China-Nigeria BIT were crucial in interpreting the treaty both at the tribunal and in the British and American courts where Zhongshan applied for the enforcement of the Award. The interpretation of “investment” in the BIT, the “fork-in-the-road” clause, and the jurisdictional arguments by Nigeria underscore the complex substantive and procedural issues that the tribunal resolved. Crucially, the tribunal drew on customary international law to attribute the conduct of a constituent state (Ogun State government) to a sovereign state (Nigeria). One of the legal implications of the attribution for the China-Nigeria BIT is that the commitments of the state parties in the BIT are binding upon them, their nationals, constituent states, and state organs in their investment relations with one another. This is notwithstanding the separate legal existence of the constituent states. This case study underscores how Zhongshan (and any other Chinese company) can rely on the provisions of the China-Nigeria BIT to invoke the international investment arbitration regime to hold Nigeria accountable for the unfair and discriminatory treatment of their investment. Further, Zhongshan had to go to a domestic court of signatories to the New York Convention to obtain an order to enforce the arbitral Award against Nigeria. In this connection, Zhongshan has applied to enforce the award in the American, British, and Canadian courts, respectively. Although the process for recovering the other party’s assets may take some time, as in this case, Zhongshan has made some progress by seizing Nigeria’s aircraft on the orders of a Canadian court.

In light of the above, the following questions may inform a discussion of the legal issues:

1. What are the core objectives of the China-Nigeria BIT and how does the Zhongshan case demonstrate their fulfillment (or not)?

2. Are there any legal or practical difficulties in attributing, as the tribunal did, the conduct of a sub-state actor to a sovereign state with a thirty-six-state structure and a federal capital territory?Footnote 85

3. What types of arbitration are eligible to be recognized and enforced under the New York Convention? What are some of the legal procedures that Zhongshan followed to enforce the Award in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

This case study demonstrates that the arbitrary use of governmental power against a foreign investor is detrimental to national economic development. The two key national economic objectives of establishing the Zone are to promote manufacturing and diversify the Nigerian economy which has been a petro-economy since the 1980s. The Zone had economic prospects as could be seen in the generation of significant tax revenue for the host government and job creation for the local population, but the revenue stream for the government and job prospects appear to be lost due to the sudden departure of Zhongshan and the monetary value of the arbitral award. Further, the Ogun State government justified the harassment, torture, detention, and seizure of the travel documents of some of Zhongfu’s staff by Nigerian police on trumped-up fraud and misrepresentation charges. However, the arbitration proceeding shows that the allegations of fraud and misrepresentation were unfounded.Footnote 86

In this context, consider the following:

1. How can the Nigerian government prioritize its economic development and enable a conducive and transparent business climate? How should the Nigerian government put in place policy processes that would engage in sustainable trade and investment agenda-setting, policy formulation, implementation, and evaluation? What type of policy objectives and reforms can the Nigerian government pursue to improve the business landscape and drive and optimize sustainable development?

2. How can the outcome of the investment arbitration discussed in this case study contribute to policy and legal springboards that may result in responsive and responsible regulation of inbound foreign investments by the Nigerian government?

3. Is there any policy role for the Export-Import Bank of China in terms of financial-related policy support for a Chinese company like Zhongshan?

5.3 For Business School Audiences

Zhongshan’s investment in a country such as Nigeria with a weak regulatory system exposed the company and its officers to a variety of risks such as loss of investment without compensation, risk to life, and loss of liberty, among other things. These risks were beyond the company’s control and may be difficult to prevent. Zhongshan, however, employed various strategies to respond to and mitigate the risks. The strategies include a request to Nigeria for negotiation and settlement, Chinese diplomatic and consular interventions from Lagos, domestic lawsuits against the organs of the Nigerian federal government and Ogun State government, and investment arbitration in Singapore and the United Kingdom. Every investor’s experience in the Nigerian regulatory landscape will differ and may warrant Zhongshan’s and other mitigating approaches. The nature of the risks and investment landscape, among other considerations, will inform the company’s decision or mitigating strategies.

Based on the foregoing, discuss the following:

1. What can be learned about investment protection from Zhongshan’s strategies in Nigeria?

2. Assuming that you are an investment analyst or risk manager in a Chinese company that is planning to invest in Nigeria, what can you identify to your company officers as the types of risks that could arise in the context of their prospective investment?

3. What are some of the mitigating strategies that you can draw from this case study to advise the company officers on how the company can navigate the risks and local challenges in its Nigerian operations?