Probiotics are living micro-organisms that are present in specific numbers in the digestive system and that have beneficial effects on the host. In recent years, because of the relationship between intestinal microbiota and human health, interest in probiotic products that have the capacity to alter the microbiota profile has gradually been increasing(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1,Reference Vandenplas and Huysentruyt2) . The most common group of probiotic products is fermented yogurt and milk products(Reference Köroğlu, Bakır and Uludağ3). Breast milk is indicated as a symbiotic nutrient that contains both prebiotics (breast milk oligosaccharides) and probiotics (Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus)(Reference Vandenplas and Huysentruyt2,Reference Güney and Çınar4) . Following the breast-feeding period, the nutrients taken in during the transition to nutritional supplements shape the microbiota, as does the nutritional model. Giving age-appropriate nutrients to infants increases the variety of bacteria in their intestines and begins to change the bacterial composition. The intestinal microbiota reach the composition of adult microbiota at around the ages of 2–3(Reference Özdemir and Demirel5). In addition to their presence in food products, probiotics are also available in tablet, powder, sachet and capsule forms(Reference Köroğlu, Bakır and Uludağ3). Although there are as yet no statistical data on this topic, the market for food containing probiotic cultures is expanding. In many countries, probiotics are available to buy from grocery stores and health food shops without prescription or professional advice(Reference Ceyhan and Alıç6). Milk products (bio-yogurt, fermented milk, cheese, lactose drinks), liquid supplements and probiotic products that are marketed for weaned and young infants are the main representatives of this trend today(Reference Viana, Cruz and Zoellner7). Because living bacteria are present in breast milk, probiotics are now included in some baby formulas in a number of countries around the world(Reference Vandenplas and Huysentruyt2,Reference Ceyhan and Alıç6) .

There are many studies evaluating the potential beneficial effects of probiotics for the treatment and prevention of various paediatric diseases. The most common objects of study are acute gastroenteritis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, antibiotic-associated diarrhoea, necrotising enterocolitis, constipation, allergic diseases, infantile colic, obesity and upper respiratory infections, such as flu, cold, sinusitis, otitis media, as well as lower respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia and bronchitis(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1,Reference Özdemir and Demirel5,Reference Arıca, Arıca and Özer8,Reference Usta and Urgancı9) . Important studies have demonstrated that the usage of probiotics during pregnancy and in infancy prevents allergic diseases that are likely to emerge in childhood and are not hereditary(Reference Pelucchi, Chatenoud and Turati10,Reference Bertelsen, Brantsæter and Magnus11) . Research has also shown that the probiotic structure in autistic children’s intestines is damaged and that probiotic supplements are important during treatment(Reference Green, Pituch and Itchon12–Reference Çetinbaş, Kemeriz and Göker14). Furthermore, probiotics help to reconstruct the intestinal microflora damaged as a result of daily living (diet, stresses) or the use of antibiotics in newborns. Probiotics prevent damage occurring to the intestinal microflora by controlling the increase of bacteria, ferment and mould(Reference Vandenplas and Huysentruyt2,Reference Çetinbaş, Kemeriz and Göker14) .

The efficiency of probiotics depends on the types and strains of bacteria as well as the dosage and length of use(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1). For maximum efficiency, it is recommended that probiotics be used every day(Reference Usta and Urgancı9). However, additional evidence is still needed on probiotic use in infants: although probiotic use in healthy infants is generally agreed to be safe, there is a consensus that more reliable evidence is needed, and that the long-term effects should be evaluated(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1). Studies have shown that health professionals and consumers worldwide consume probiotics for health reasons; however, they generally do not have enough knowledge about the products and the appropriate ways to use them(Reference Viana, Cruz and Zoellner7,Reference Balkış15–Reference Amarauche20) .

There are a limited number of studies in the world investigating the use of probiotics by mothers for their infants and during pregnancy(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1,Reference Andersen, Michaelsen and Laursen19,Reference Gumede and Chelule21,Reference Kirui, Nguka and Wango27) . The knowledge mothers have about probiotics, their attitudes towards them and how they use them during pregnancy and for their infants has not previously been studied in Turkey. Given the increasing availability of probiotics and the latest scientific evidence, it is clearly important that practitioners know which diseases probiotics are effective for, and how they should be used during pregnancy and for infants. The purpose of this research was thus to find out what mothers in Turkey knew about probiotics and what their attitudes were towards them. In addition, the study investigated how mothers used probiotics during pregnancy and for their infant, and what factors influenced them in this.

Methods

Study design and sampling

The current study had a cross-sectional design and was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. The population and sample of the study consisted of mothers with infants between 6 months and 2 years old who had been hospitalised in the paediatric clinics of a university and a public hospital of one province in the central Black Sea Region in Turkey between 28 May and 31 October 2018 (N 519). The inclusion criteria were agreeing to participate, not having any hearing problems and being able to understand Turkish.

Instruments

Data were collected using the Sociodemographic Information Form and the Probiotic Information and Attitudes Form. The questionnaires were pre-applied to ten mothers in the clinic and were revised and finalised according to their responses.

Socio-demographic Information Form

This form consisted of eight questions about the mother’s age, education, employment status, income status, the family structure, age of the child, gender of the child and whether they were actively breast-feeding.

Probiotic Information and Attitudes Form

This form consists of two parts and included thirty questions to determine how mothers used probiotics during pregnancy and for their infant, and their knowledge about and attitudes towards probiotics. The first part contained ten questions about the mothers’ use and knowledge of probiotics; these questions were developed by researchers in line with the literature(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1,Reference Balkış15,Reference Betz, Uzueta and Rasmussen17,Reference Gumede and Chelule21) . They included the following: What are probiotics in your opinion? Which foods are probiotics in? Do you think breast milk is a probiotic food? How often did you use probiotic foods during your pregnancy/How often do you give them to your baby? What were/are your reasons for this? Have you benefited from this? Where/from whom did you first learn about probiotics?, etc. Probiotics were defined as live micro-organisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host(22,Reference Kılıç and Şahin23) . The participants who were able to describe probiotic in this way were evaluated as ‘knowing about’ them, while those who were not able to do so were evaluated as ‘not knowing about’ probiotics. The second part of the form was about information and the mothers’ attitudes and consisted of twenty questions with a five-point grading system using the statements, ‘Strongly agree’, ‘Agree’, ‘Neither agree nor disagree’, ‘Do not agree’ and ‘Strongly disagree’. Permission was granted to use the form(Reference Balkış15).

Data collection

The data collection tools were filled out during face-to-face interviews by three members of staff who had been trained by the researchers. Verbal and written consent was obtained from each mother. The interviews were conducted in two stages. In the first stage, the mothers were asked what probiotics were, whether they knew of any products containing probiotics and whether they knew if breast milk was probiotic. In the second stage, for mothers who did not know what probiotics were, the interviewers provided them with a definition and then asked the remaining questions. The collection of data took approximately 15–20 min.

Statistical analysis

The research data were encoded in the SPSS 20 package software. The statistical significance of the data was assessed at P < 0·05. The data were tested using descriptive (frequency, percentage) and χ 2 inferential statistical models.

Dependent and independent variables

The dependent variable of the study was determined to be the level of knowledge, and the attitudes and practices of the mothers regarding probiotic use during pregnancy and for infants between 6 months and 2 years old.

The independent variables were the mother’s age, education, employment status (whether or not they were current in paid employment), income status (low, middle, high), family structure (nuclear or extended), the age and gender of the child and actively breast-feeding status (whether they were continuing to breast-feed their child at the time the study occurred).

Results

Of the 519 mothers, 20·2 % were able to say what probiotics were before being given the definition, 33·1 % of them knew which products contained probiotics and 49·7 % of them knew that breast milk contains probiotics.

Table 1 compares the mothers’ socio-demographic variables with their knowledge of probiotics. There was a statistically significant difference between the mothers’ knowing what probiotics were and which products contained probiotics, and their age, education, employment status, income status, family structure and whether they were actively breast-feeding (P < 0·05). The mothers who knew which products contained probiotics and what probiotics were had a higher level of education, a higher income, were employed, had nuclear families and were actively breast-feeding. The mothers who were 25 years old or younger were less likely to know what probiotics were and which products contained them. However, no statistically significant difference was found between them in terms of children’s age and gender (P > 0·05). There was a statistically significant difference between mothers’ knowledge that breast milk contains probiotics and their age, education, employment status, income, family structure, child’s age and breast-feeding (P < 0·05). The mothers who knew that breast milk contains probiotics had a higher level of education, a higher income, were employed, had nuclear families and were actively breast-feeding. The mothers who were 25 years old or younger and whose children were 1 year old or less were not as likely to know breast milk contains probiotics. However, no statistically significant difference was found between them in terms of gender of the child (P > 0·05) (Table 1).

Table 1 Mothers’ knowledge of probiotics in comparison with their socio-demographic variables

* χ 2/P = chi-square test/P significance value.

Table 2 shows mothers’ sources of information and reasons for using probiotics during pregnancy and for their infants. 21·2 % of the mothers stated that they used products with probiotics during their pregnancy to strengthen their immune system, while 17·5 % of them used probiotics for digestive problems. 26·2 % of them used probiotics to strengthen their infant’s immune systems, while 18·7 % of them used them for digestive problems. 98·9 % of the mothers who used probiotics during pregnancy and 99·4 % of them who used them for their infants thought that they were beneficial (Table 2).

Table 2 Mothers’ reasons and sources of information for the use of probiotics during pregnancy and for their infants

* More than one choice is marked.

When the mothers were asked what their sources of information about probiotics were, 59·3 % of them stated that they had not learned about probiotics during their pregnancy, while 11·4 % of them had heard about them from the TV/radio/newspapers, etc. and 10·6 % had been informed about them by their doctors. In terms of using probiotics for their infants, 23·3 % stated that they had never heard anything about doing this, 26·0 % of them had heard about doing this from other sources (books, neighbours, etc.) and 11·0 % of them had been informed that they could do this by a nurse (Table 2).

Figure 1 shows the mothers’ use of probiotic products during pregnancy and for their infants. Cheese (92·9 %), homemade yogurt (91·5 %), ayran (90·9 %), butter (90·4 %), natural cow’s milk (76·9 %), ice cream (72·4 %) and pickles (70·7 %) were the most common probiotic foods consumed by mothers during pregnancy. They most commonly fed their infants ready-made baby formulas (64·5 %), home-made yogurt (64·0 %), cheese (54·4 %) and ayran (57·4 %) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Mothers’ use of probiotic products during pregnancy and for their infants* (%). ![]() , during pregnancy;

, during pregnancy; ![]() , for their infants

, for their infants

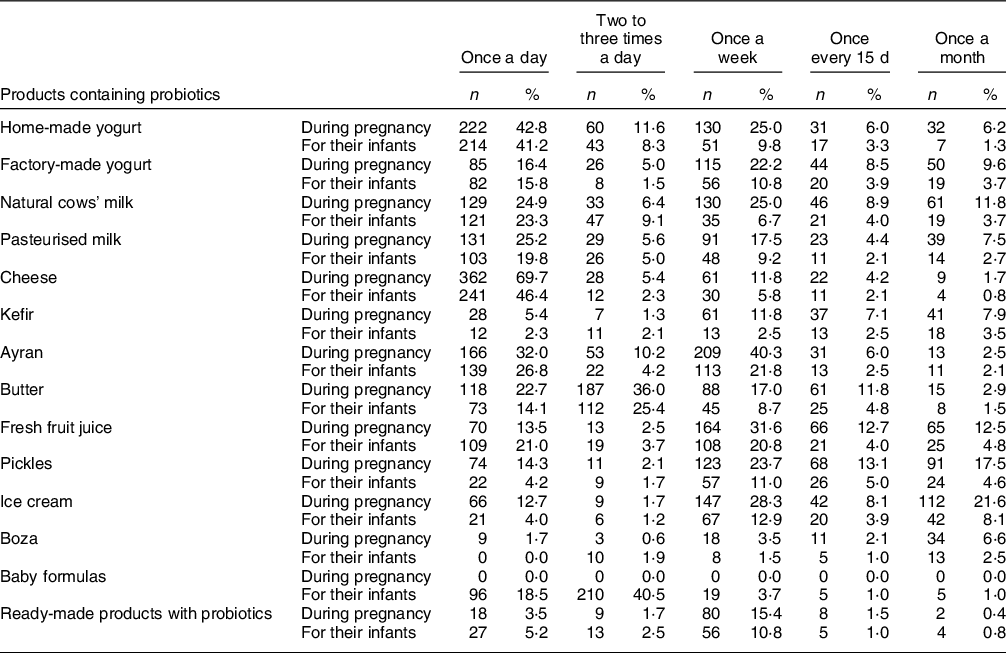

Table 3 shows the mothers’ frequency of use of products containing probiotics during their pregnancy and for their infants. The products containing probiotics which they consumed either once or two to three times a day during pregnancy were cheese (69·7 and 5·4 %, respectively), butter (22·7 %; 36·0 %), home-made yogurt (42·8 %; 11·6 %), ayran (32·0 %; 10·2 %) and natural cows’ milk (24·9 %; 6·4 %). The products containing probiotics they fed their infants either once or two to three times a day were baby formulas (18·5 and 40·5 %, respectively), cheese (46·4 %; 2·3 %), home-made yogurt (41·2 %; 8·3 %), butter (14·1 %; 25·4 %) and natural cow’s milk (23·3 %; 9·1 %) (Table 3).

Table 3 Mothers’ frequency of use of products containing probiotics during their pregnancy and for their infants

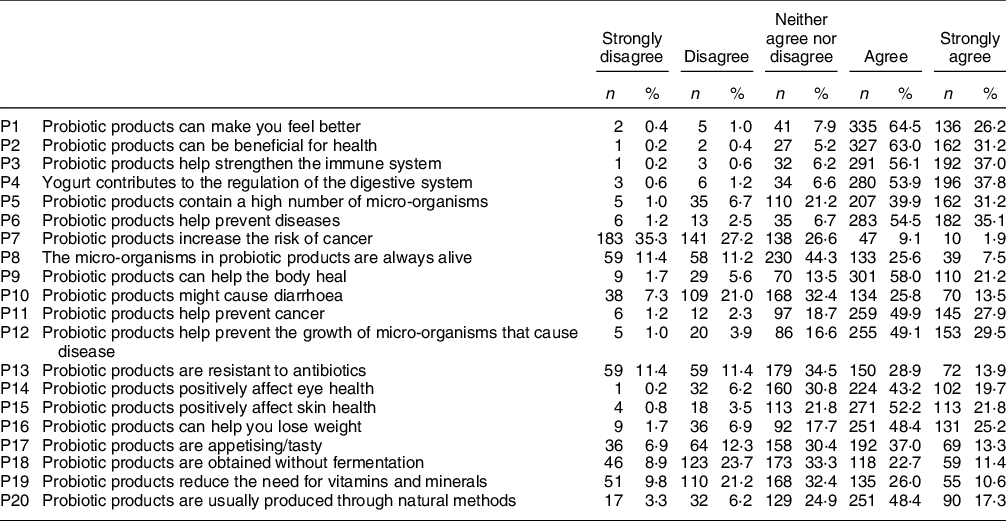

Table 4 shows the mothers’ knowledge and attitudes regarding products containing probiotics. More than 90 % of the mothers responded ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ to statements P1, P2, P3 and P4, and more than 70 % of them responded ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ to statements P5, P6, P9, P11, P12, P14, P15 and P16.

Table 4 Mother’s knowledge and attitudes regarding products containing probiotics

Discussion

Given that the amount of research on the positive effects of probiotics on health is increasing, it is necessary to assess mothers’ knowledge and attitudes regarding probiotics and how they actually use them. There is a limited amount of information available in the literature on the use of probiotic products during pregnancy and childhood. Research indicates that the use of probiotics differs in different cultures and societies(Reference Andersen, Michaelsen and Laursen19). The current study was conducted to assess mothers’ knowledge and attitudes regarding probiotics and how they use them during pregnancy and for infants of between 6 months and 2 years old. It was found that although the mothers did not have sufficient knowledge about what probiotics were, about which products contained probiotics and about whether breast milk contains probiotics, they had, nevertheless, been using natural products with probiotics daily. The mothers did not state whether they had chosen to buy probiotic products or whether they had been prescribed them by their doctors. At the beginning of the research, they were asked what probiotics were and which products contained probiotics. 20·2 % of them were able to say what probiotics were, 33·1 % of them knew which products contained probiotics and 49·7 % of them knew that breast milk contains probiotics. In contrast with the findings of this research, in another study examining mothers’ knowledge about probiotics and their use of them for their infants, the percentages of mothers who had heard about probiotics (99·3 %) and who knew that probiotics consist of bacteria (87·0 %) were found to be high(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1). In another study, 65·2 % of the participants were found to be familiar with the term, while 32·9 % of them had not heard it before(Reference Chin-Lee, Curry and Fetterman24). Many studies have indicated that people in general, including students, do not know enough about probiotics(Reference Viana, Cruz and Zoellner7,Reference Balkış15–Reference Andersen, Michaelsen and Laursen19,Reference Al-Nabulsi, Obiedat and Ali25) . Likewise, in the research by Amarauche, health professionals’ level of knowledge and awareness of probiotics were found to be low(Reference Amarauche20). In research carried out on health professionals in Turkey, 67·4 % of them responded that their knowledge of probiotics was ‘moderate’ while 16·3 % said that it was ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’(Reference Altındiş, İnci and Elmas26). These findings are not surprising as the use of probiotics is generally not promoted in Turkey, whether among health professionals, in the food industry or in advertising.

The current study found that there was a relationship between the mothers’ age, education level, employment, income, family structure and actively breast-feeding, and whether they knew what probiotics were, which products contained probiotics and that breast milk contains probiotics. In contrast with this research, in the study of Bridgman et al., no significant difference was found between the socio-demographic features (age, marital status, education, income, ethnic background and place of birth) of mothers who stated that they gave probiotic products to their infants and those who did not(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1). According to another study, there was no statistically significant difference between income level, age, gender, ethnic background or education(Reference Chin-Lee, Curry and Fetterman24). These results may be due to various sociocultural factors. There is a limited amount of research on this topic in literature and it is thus important that these relationships be more extensively analysed in future studies.

According to the current study, mothers used probiotics both during their pregnancy and for their infants in order to strengthen the immune system (21·2 and 26·2 %, respectively) and to counter digestive problems (17·5 %; 18·7 %). Likewise, in the research of Betz et al. probiotics and prebiotics were defined as the most beneficial supplements for the digestive system(Reference Betz, Uzueta and Rasmussen17). In another study, it was found that the participants used probiotics to maintain gastrointestinal health (51·1 %), to bolster the immune system (40·8 %) and to reduce the side effects of medication (26 %)(Reference Chin-Lee, Curry and Fetterman24). In the research of Viana et al., 29·5 % of the participants used probiotics to lower cholesterol, while 28·3 % of them used them to cure diarrhoea(Reference Viana, Cruz and Zoellner7). A study found that 48·1 % of students who consumed probiotics used them for their ‘intestinal benefits’, and 18·5 % of them used them in order to have a ‘responsive immune system’(Reference Al-Nabulsi, Obiedat and Ali25). These findings suggest that it is these kind of messages about the benefits of probiotics that are most frequently communicated.

Nevertheless, the mothers who participated in the current study stated that they had learned very little from the media, health professionals or other sources of information about the use of probiotics. Other studies have found that participants had learned more about probiotics than was the case in the current research. For example, one study found that most information about probiotics had been received from the media(Reference Betz, Uzueta and Rasmussen17). In line with the current research, another study found that most of the mothers included had heard about probiotics through the media (43·3 %), followed by 25·2 % from a friend and 20·3 % from a health professional (doctor, pharmacist or midwife)(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1). In the research of Chin-Lee et al., the most common source of information about probiotics was a friend (26·5 %), followed by a doctor’s recommendation (22·4 %)(Reference Chin-Lee, Curry and Fetterman24). According to another study, students learned about probiotics in classes (35·9 %), from TV advertisements (34·2 %), TV programmes (28·2 %), health professionals (19·7 %) and newspapers/other media (8·5 %)(Reference Al-Nabulsi, Obiedat and Ali25). These findings indicate that mothers are not being sufficiently informed by health professionals and the media. Health professionals need to better explain the protective and beneficial effects of probiotics to society in general and, in particular, to be clear about how products containing probiotics can be consumed during pregnancy and early childhood.

In the current study, most of the mothers stated that probiotics are found in milk and milk products. Likewise, in the research of Viana et al. most of the participants mentioned that probiotics are mostly found in milk and milk products(Reference Viana, Cruz and Zoellner7). Similarly, in research carried out on in-patients, 72 % of the participants defined yogurt as being probiotic(Reference Betz, Uzueta and Rasmussen17). In another study, 4·6 % of the students named yogurt, 3 % of them named milk and 1·5 % of them named cheese as sources of probiotics(Reference Al-Nabulsi, Obiedat and Ali25). In a descriptive study examining the nutrition of children under the age of 5 in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, it was found that more than 90 % of caregivers stated that fermented milk (lacto), yogurt and fermented maize lapel were probiotics(Reference Gumede and Chelule21). According to another study, most probiotic users (79·6 %) preferred to consume probiotic food products rather than capsules, pills or powders(Reference Chin-Lee, Curry and Fetterman24). Many women may prefer milk and milk products as a source of probiotics because these products are widely advertised and readily available in the retail market. Knowing that milk and milk products contain probiotics is important as it allows consumers to make a positive choice to consume them for their health benefits.

The findings of this research indicate that the women used probiotics more frequently during pregnancy than for their infants. According to one study, 89·3 % of mothers consumed products with probiotics for themselves, while only 50·8 % fed them to their infant(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1). Another study found that almost all the caregivers (99 %) used fermented products (milk, yogurt and fermented maize porridge) to nourish children under 5(Reference Gumede and Chelule21). According to the research carried out by Kirui et al. in Kenya, the use of mursik, which is a probiotic product, was low for children under 5, and families did not have enough information about mursik(Reference Kirui, Nguka and Wango27). The findings of the current study show that the dietary habits of the mothers were very traditional and that they did not have enough knowledge about the benefits of probiotics.

The findings regarding the attitudes of the mothers who participated in the study were positive. Similar to the current study, several other studies also found that the participants had positive beliefs about, and attitudes towards, probiotics(Reference Bridgman, Azad and Field1,Reference Andersen, Michaelsen and Laursen19,Reference Gumede and Chelule21) . Further investigation is needed into beliefs about, and attitudes towards, probiotics, especially during pregnancy and parenthood.

Strengths and limitations of the study

One strength of the study was that the sample population (N 519) was receiving health care in the paediatric clinics of a university hospital and a public hospital. These hospitals are health institutions that are easily accessible to mothers from all segments of society (low, middle and high income, and educated/uneducated). The large sample size increased the ability of the study to be representative of the society. In addition, the pilot study allowed the questionnaire to be assessed for clarity and technical errors. The current study thus provides important implications for future research in the area about use of probiotics.

However, the fact that the study was conducted in the paediatric clinics of only two hospitals in one province of Turkey is a limitation and means that the study cannot be generalised to all women in this society.

Conclusion

Given the increase in the number of studies demonstrating the beneficial health effects of probiotics, it is important to inform mothers about their proper use. The current study shows that mothers’ knowledge about, and use of, probiotics is not yet adequate. A number of recommendations can be made in the light of these findings. Evidence-based information should be provided, and mothers should be better educated about what probiotics are, as well as their benefits and disadvantages. Studies should be conducted to find how much, and what kind of, information health professionals are giving to pregnant women and women with children about how to use probiotics. It is, however, important to keep in mind that the results of the current study cannot be generalised to the population and only represent the women who were present in the hospitals at one specific time. Future research should include larger sample populations that are more representative of each society in general.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would particularly like to thank the women who participated in the study. Additionally, we would like to thank the trained staff members who contributed to our research during the questionnaire phase. Financial support: The authors declare that the current study received no funding. Conflict of interest: The authors did not report any conflict of interest for the current study. Authorship: Ü.Ç.G. has contributions such as research design, data analysis, writing the first draft of the article and presenting the article to the journal. A.K. has contributions such as research design, writing the article and presenting the article to the journal. The authors contributed to the article and they reviewed the article from a critical perspective. The final paper was approved by the authors. Ethics of human subject participation: Before starting the study, the ethics committee of Gaziosmanpaşa University Faculty of Medicine approved the current study. Ethics committee decision number is 18-KAEK-021. Verbal and written consent was obtained from each mother. During the study, the provisions of Helsinki Declaration were respected.