The WHO recommends that low birth weight infants receive donor human milk (DHM) when mother’s own milk is not available due to evidence that it decrease the risk of necrotising enterocolitis(Reference Quigley, Embleton and McGuire1,2) . Globally, DHM is typically produced by country-level milk banking networks that serve as a conduit between the recipient infants and the donors who provide the milk(3–5). Although the recommended recipient for DHM is primarily the pre-term infant(2,6) , a recent review reported that DHM is also being used in other populations including healthy term infants and term infants with health risks. A 2020 report from a Virtual Communication Network of global milk banking leaders estimated that at least 800 000 infants receive DHM around the world annually(Reference Shenker, Staff and Vickers7,Reference McCune and Perrin8) .

To ensure the quality and safety of DHM, human milk banks use similar hazard analysis and critical control points, where protocols are used in every step of the process, from donors screening until milk distribution(9). Holder pasteurisation is the main processing technique used in milk banks, and although it inactivates virus such as HIV and cytomegalovirus, it also alters the milk composition(Reference Peila, Moro and Bertino10). A recent review found over forty studies that had evaluated the impact of Holder pasteurisation on DHM, suggesting that there is a growing body of knowledge about this technique(Reference Peila, Moro and Bertino10).

While there are multiple reviews on DHM recipients and milk banking processes, the donors to milk banks have not been systematically studied. A recent report by the WHO noted that ‘the motivations behind donating human milk remain under-researched’(Reference Fang, Grummer-Strawn and Maryuningsih11). Other information about milk bank donors may provide important insights regarding donor recruitment and the nutritional care of infants receiving DHM. For example, a donor’s birth type (term v. pre-term) and milk type (colostrum, transition and mature) could influence the composition of the milk being collected by the milk banks(Reference Mills, Coulter and Savage12). Therefore, the aim of this review is to explore what is currently known about human milk bank donors globally and identify gaps for future research.

Methods

A systematic scoping review was conducted to investigate what is known about milk bank donors. The objective of a scoping review is to map and summarise the information available for a research topic and to identify gaps where more research is needed(Reference Arksey and O’Malley13). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were used to guide this review. The databases used to identify original research articles were PubMed and Scopus. Search terms utilised for both databases included ‘Milk bank*’ AND ‘donors’ NOT (composition OR pasteuri* OR nutri*). Additional studies were located by hand-reviewing bibliographies of the studies identified through the primary search.

Original research articles about milk bank donors that were published before August 2020 were included in this review. Studies were excluded if they were (1) about donor milk composition and/or pasteurisation only, (2) about infant feeding practices and/or infant nutrition only, (3) in languages that were not English, (4) not original articles or (5) not about milk bank donors (e.g. peer-milk sharing only). Two researchers (BGS and MTP) independently evaluated all study titles, abstracts, and full papers for exclusion or inclusion criteria, and differences were resolved after each review step by discussion.

Included studies were independently abstracted by two researchers (BGS and MTP) into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for the following information: study location, study design, study population, study objectives, data collection methods, variables related to milk bank donors, results and funding source. Studies that used multiple years of milk bank donor data were classified as semi-longitudinal study design, since some donors may have appeared more than once in data that spanned several years. Abstracted data were reviewed by two researchers (BGS and MTP) and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Demographic data from one study combined donor and non-donor information and could not be interpreted; therefore, these demographic data were not reported in the results.

To organise study variables, an iterative process was used by two researchers working together to develop and refine a classification system of main categories and sub-categories for study variables. Categories and sub-categories used to classify variables included (1) Donor Demographics (Demographics) which included Age, Marital Status, Race-Ethnicity, Education, and Employment Status, (2) Donor Clinical Characteristics (Clinical) which included Birth History (e.g. number of children, parity, delivery term, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions), Diseases (e.g. donor health conditions) and Prenatal Care, (3) Donor Lifestyle Characteristics (Lifestyle) which included Diet, Exercise, Legal Drug Use (e.g. nicotine, caffeine, and alcohol) and Illegal Drug Use, (4) Lactation and Breast-feeding Experience (Breast-feeding) which included Breast-feeding History (e.g. breast-feeding experience and problems), Clinical Support, Milk Expression Practices, and Beliefs About the Value of Milk, (5) Donor Experience and Beliefs (Experience/Beliefs) included Reasons/Enablers for Donation, Barriers for Donation and Donor Identity and (6) Donation Patterns (Patterns) included Donation Volume, Donor Type (first-time or repeat), Milk Type (colostrum – 0–7 d, transition milk – 7–21 d, mature milk – over 21 d)(14), and Donation Duration.

The primary source of bias considered was selection bias, if donors included in a study were potentially not representative of the broader donor population. Studies were identified as possibly having selection bias if they did not discuss participant selection, had low participation rate (below 60 %)(Reference Fincham15) or included a limited sampling frame (e.g. only bereaved donors, only donors active on social media). Selection bias was evaluated independently by two researchers and discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Results

A total of 181 studies were identified through Scopus, 84 through PubMed and 8 through hand-review of bibliographies (Fig. 1). After excluding duplicates (n 70), a total of 203 studies were screened. After a review of abstracts and titles, 154 articles were excluded leaving 49 articles for full-text review. Twenty-one studies were excluded after full-text review leaving twenty-eight studies in this scoping review about human milk bank donors(Reference Azema and Callahan16–Reference Oreg and Appe43).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the literature search process used to identify studies using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist

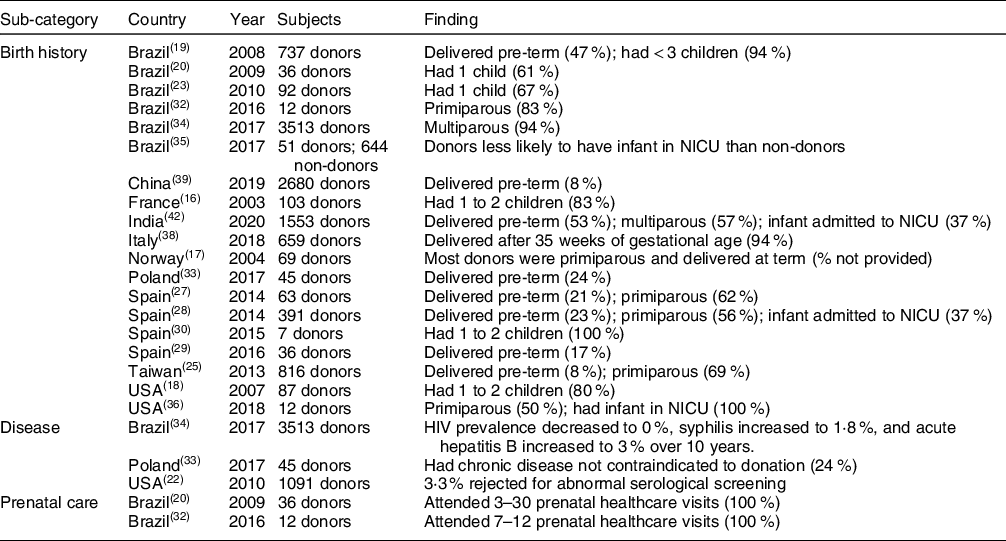

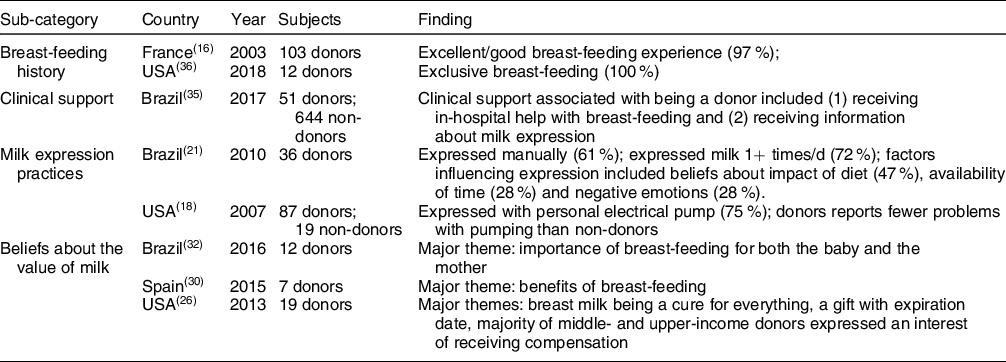

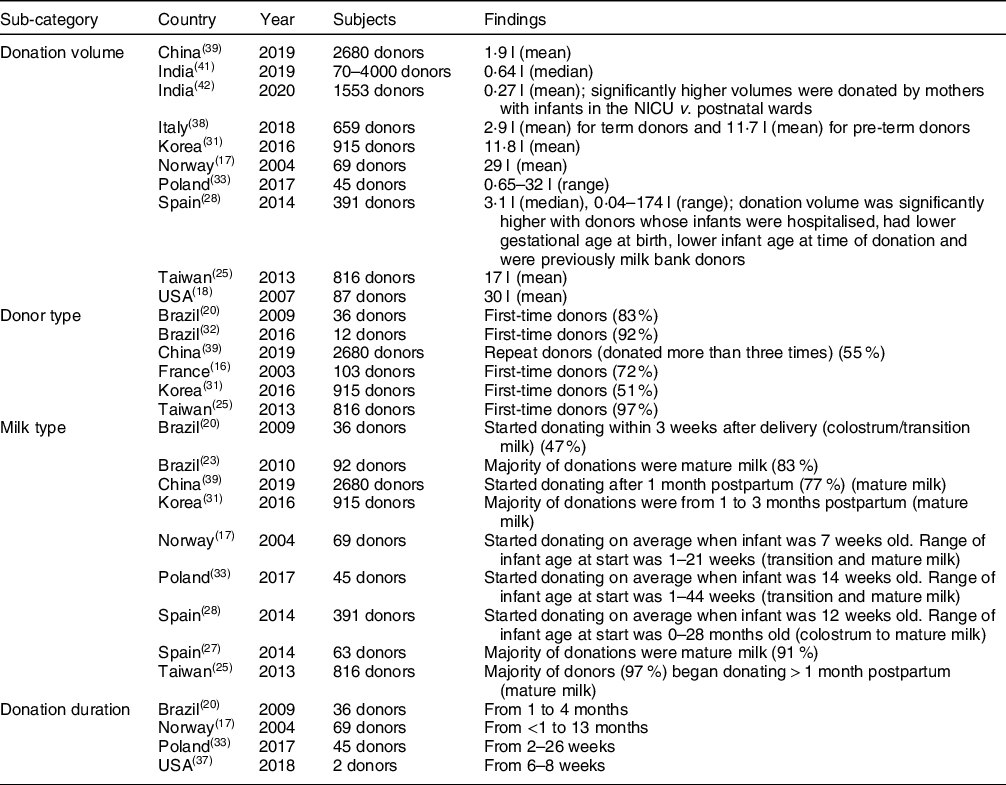

Studies in this systematic review were published between 2003 and 2020 (Table 1) and included 2 to 4000 donors. Eight studies were conducted in the USA, seven in Brazil, four in Spain, two in India, and individual studies were conducted in France, Norway, Poland, Italy, Taiwan, Korea and China. A qualitative design was used in eight studies, which allows for rich exploration of the donors’ lived experiences. Qualitative studies were predominantly conducted in the USA and had a small sample size (2–21 donors and 80–107 online testimonials or images). Data collection methods used in the studies included interviews, questionnaires, chart reviews and online content analysis. In most of the studies, donors were recruited from a single milk bank (n 16). Ten studies (36 %) presented possible selection bias (Table 1). The number of studies reporting variable types included (1) Donor Demographics (n 19; Table 2), Clinical Characteristics (n 20; Table 3), (3) Lifestyle Characteristics (n 4; Table 4), (4) Lactation/Breast-feeding Experiences (n 8; Table 5), (5) Donor Experiences (n 16; Table 6) and (6) Donation Patterns (n 16; Table 7).

Table 1 Summary of studies included in the systematic scoping review of human milk bank donors

VFI, volunteer functions inventory; PANAS, positive and negative affect schedule; WIC, Women, Infants, and Children programme; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Table 2 Demographic information about milk bank donors

Table 3 Clinical information about milk bank donors

NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Table 4 Lifestyle characteristic information about milk bank donors

Table 5 Lactation and breast-feeding experience information about milk bank donors

Table 6 Donor experience information about milk bank donors

Table 7 Donation pattern information about milk bank donor

NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Discussion

Despite reports that there are now over 600 milk banks operating around the world(44), and over 800 000 infants annually who receive DHM(Reference Shenker, Staff and Vickers7), studies about milk bank donors are often limited to a single study per geography with significant heterogeneity in the variables reported.

Donor demographics

Age was the most commonly reported demographic variable, with some initial geographic differences observed. Specifically, donors were predominantly in their early- to mid-twenties in Brazil and India (based on mean donor age or prevalence of donors by age group)(Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference de Alencar and Seidl21,Reference Koyashiki, Paoliello and Matsuo23,Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32,Reference Kupek and Savi34,Reference Nangia, Ramaswamy and Bhasin42) , while donors were predominantly in their early-thirties in France, Korea, Norway, Poland, Spain, Taiwan and the USA(Reference Azema and Callahan16–Reference Osbaldiston and Mingle18,Reference Chang, Cheng and Wu25,Reference Escuder-Vieco, Garcia-Algar and Pichini27–Reference Jang, Cho and Kim31,Reference Barbarska, Zielińska and Pawlus33) . There were also geographic differences in education levels among donors, with studies conducted in Brazil reporting that the majority of donors were not college-educated compared to mostly college-educated donors in China, Norway, Spain, Taiwan and the USA(Reference Lindemann, Foshaugen and Lindemann17,Reference Pimenteira Thomaz, Maia Loureiro and da Silva Oliveira19,Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Koyashiki, Paoliello and Matsuo23,Reference Chang, Cheng and Wu25,Reference Chang, Cheng and Wu25,Reference Machado, Campos Calderón and Montoya Juárez30,Reference Liu, Han and Wei39) . Across all geographies, donors were predominantly married or living with a partner(Reference Azema and Callahan16,Reference Osbaldiston and Mingle18–Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Machado, Campos Calderón and Montoya Juárez30,Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32,Reference Candelaria, Spatz and Giordano36) . Limited information was available on race-ethnicity(Reference Osbaldiston and Mingle18,Reference Koyashiki, Paoliello and Matsuo23,Reference Candelaria, Spatz and Giordano36) . No information was collected about gender in any of the studies, suggesting that donor gender may have been assumed in prior research. While this scoping review identified some differences in donor demographics across geographies, interpretation of this information requires more context related to the local setting.

Donor clinical characteristics

Birth history frequently included a donor’s number of children. Results varied by geographies, with some studies reporting that donors were predominantly primiparous and others predominantly multiparous(Reference Azema and Callahan16–Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Koyashiki, Paoliello and Matsuo23,Reference Chang, Cheng and Wu25,Reference Escuder-Vieco, Garcia-Algar and Pichini27–Reference Machado, Campos Calderón and Montoya Juárez30,Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32–Reference Candelaria, Spatz and Giordano36,Reference Quitadamo, Palumbo and Cianti38,Reference Liu, Han and Wei39,Reference Nangia, Ramaswamy and Bhasin42) . The percentage of donors that had pre-term births were in the minority in most studies (8–24 %)(Reference Chang, Cheng and Wu25,Reference Escuder-Vieco, Garcia-Algar and Pichini27–Reference Escuder-Vieco, Garcia-Algar and Joya29,Reference Barbarska, Zielińska and Pawlus33,Reference Liu, Han and Wei39) , though two studies in India and Brazil reported the approximately half of donors gave birth pre-term(Reference Pimenteira Thomaz, Maia Loureiro and da Silva Oliveira19,Reference Nangia, Ramaswamy and Bhasin42) . Donor birth term could influence the composition of some nutrients in donor milk if donations are made in the first weeks postpartum(Reference Underwood45,Reference Gidrewicz and Fenton46) , suggesting that this may be useful donor data to regularly collect. Information regarding donors’ diseases/conditions(Reference Cohen, Xiong and Sakamoto22,Reference Barbarska, Zielińska and Pawlus33,Reference Kupek and Savi34) and prenatal clinical care was limited(Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32) . Data on characteristics of the donor’s child beyond birth term were also scarce. For example, no studies reported the sex of the donor’s infant, and only a few studies reported hospitalisation status.

Donor lifestyle characteristics

There is limited research regarding donors’ lifestyle characteristics including diet, exercise, legal and illegal drug use, which does not allow for any type of synthesis across regions. While milk banks screen donors to ensure they are healthy, lifestyle information could be valuable, as factors associated with maternal diet and lifestyle may influence what is being transferred in the milk.

Lactation and breast-feeding experience

Donors reported similar beliefs about the importance of breast-feeding and breast milk across three geographies(Reference Pineau and Cassidy26,Reference Machado, Campos Calderón and Montoya Juárez30,Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32) . Donors’ beliefs in the value of their milk was only explored in one study, with many donors expressing the desire for compensation. Information about donors’ breast-feeding history, clinical support for lactation and milk expression practices was limited to one or two studies, suggesting this is an important area for future research to better understand the donor’s path to having excess milk for donation.

Donor Experiences and Beliefs

The most common donor experience studied was reasons/enablers for donation(Reference Azema and Callahan16,Reference Osbaldiston and Mingle18–Reference de Alencar and Seidl21,Reference Welborn24,Reference Pineau and Cassidy26,Reference Machado, Campos Calderón and Montoya Juárez30–Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32,Reference Meneses, Oliveira and Boccolini35,Reference Cole, Schwarz and Farmer37,Reference Liu, Han and Wei39,Reference Oreg and Appe43) . Common reasons for donation included altruism, having excess milk and avoiding waste(Reference Azema and Callahan16,Reference Osbaldiston and Mingle18,Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Machado, Campos Calderón and Montoya Juárez30,Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32,Reference Candelaria, Spatz and Giordano36,Reference Cole, Schwarz and Farmer37,Reference Oreg and Appe43) . Common enablers for donation were being encouraged to donate and receiving information about milk banks from healthcare providers(Reference Pimenteira Thomaz, Maia Loureiro and da Silva Oliveira19–Reference de Alencar and Seidl21,Reference Welborn24,Reference Machado, Campos Calderón and Montoya Juárez30–Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32,Reference Meneses, Oliveira and Boccolini35,Reference Candelaria, Spatz and Giordano36,Reference Liu, Han and Wei39) . Healthcare providers were reported as a major source of information in Brazil, while online sources were reported as major sources of information in Korea and China(Reference Pimenteira Thomaz, Maia Loureiro and da Silva Oliveira19–Reference de Alencar and Seidl21,Reference Jang, Cho and Kim31,Reference Liu, Han and Wei39) . Barriers for donation were only assessed in three countries and included finding time to pump, reduced milk production, limited information provided prenatally, returning to work, distance from milk bank and no support at work(Reference Osbaldiston and Mingle18,Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Machado, Campos Calderón and Montoya Juárez30,Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32,Reference Cole, Schwarz and Farmer37) . Qualitative studies that explored donor identity were all conducted in the USA and found that while the act of donating influenced mother’s identity, it had a special meaning for bereaved mothers(Reference Welborn24,Reference Cole, Schwarz and Farmer37,Reference Oreg40) .

Donation patterns

There was a wide range of reported donation volumes per donor (mean or median 0·64–30 l and range 0·04–174 l)(Reference Lindemann, Foshaugen and Lindemann17,Reference Osbaldiston and Mingle18,Reference Chang, Cheng and Wu25,Reference Sierra Colomina, García Lara and Escuder Vieco28,Reference Jang, Cho and Kim31,Reference Barbarska, Zielińska and Pawlus33,Reference Quitadamo, Palumbo and Cianti38,Reference Liu, Han and Wei39,Reference Sachdeva, Mondkar and Shanbhag41,Reference Nangia, Ramaswamy and Bhasin42) . The wide range could be attributed to the differences in milk banking requirements. For example, in Brazil, there is not a minimum donation volume(47), while in the USA some milk banks require a minimum donation of 100 ounces(48). In India and Spain, donors with infants in the NICU/hospitalised provided significantly higher volumes than donors without hospitalised infants(Reference Sierra Colomina, García Lara and Escuder Vieco28,Reference Nangia, Ramaswamy and Bhasin42) . Donor type was mostly first time (v. repeat) in all regions, although it was not widely reported(Reference Azema and Callahan16,Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Chang, Cheng and Wu25,Reference Jang, Cho and Kim31,Reference Miranda, Passos and Freitas32) . The type of milk commonly donated was mature milk, as the donations started mostly after 1 month postpartum(Reference Lindemann, Foshaugen and Lindemann17,Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Chang, Cheng and Wu25,Reference Escuder-Vieco, Garcia-Algar and Pichini27,Reference Sierra Colomina, García Lara and Escuder Vieco28,Reference Jang, Cho and Kim31,Reference Barbarska, Zielińska and Pawlus33,Reference Liu, Han and Wei39) . This suggests that donors are frequently providing milk that is likely lower in protein than the colostrum and transition milk that would normally be provided by an infant’s own mother in the early postpartum period. There was limited information about donation duration (range 2 weeks to 13 months)(Reference Lindemann, Foshaugen and Lindemann17,Reference de Alencar and Seidl20,Reference Barbarska, Zielińska and Pawlus33,Reference Cole, Schwarz and Farmer37) . No studies collected information regarding whether milk bank donors provided their milk elsewhere, including either selling it or sharing with a peer.

Conclusion and future direction

Although DHM banking continues to grow around the world(Reference Israel-Ballard49,Reference Mansen, Nguyen and Nguyen50) , information about the individuals who donate their milk is often limited to a single study per geography, with heterogeneity in the variables reported. Further, one-third of the studies were subject to potential selection bias. Some demographic characteristics were commonly reported across regions, while others, including gender and race, were infrequently explored, suggesting the need to incorporate these demographic variables in future research. Although donors’ experiences related to donations were frequently reported, enablers and barriers for donation differ among regions studied and not enough is known about what motivates donors to donate. Additionally, factors that could influence the nutritional profile of DHM, including birth timing (term or pre-term), type of milk donated (colostrum, transition or mature), donor diet and infant characteristics, should be more frequently collected. Other factors that have not been widely studied included donor lactation and breast-feeding history, including factors that influence why donors are pumping and amassing surplus milk and donation patterns, including whether milk bank donors are also selling milk to corporations or sharing milk with peers.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: M.T.P. conceived of the study; B.G.S. and M.T.P. planned the study; B.G.S. led data collection; B.G.S. and M.T.P. analysed data; B.G.S. wrote the first manuscript draft; B.G.S. and M.T.P. edited the manuscript and agreed on final content. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.