The recently published hexameter fragments from a late-antique palimpsest found in the Monastery of St Catherine on Mt Sinai (Sin. Ar. Nf 66) are a very important addition to our knowledge of Orphic/Dionysiac poetry, most probably related to the Orphic Rhapsodies, a twenty-four-book hexameter poem so far known only thanks to a copious indirect tradition.Footnote 1 Fragment B (in the numbering of D’Alessio Reference D’Alessio2022) preserves remains of an episode in which a child of Zeus and Persephone called Oinos, ‘Wine’, as in the Orphic Rhapsodies (303, 321, and 331 F Bernabé), occupies the throne of Zeus and is the object of one or more attacks by hostile individuals, in a context that has parallels within known quotations and allusions to the poem (296–310 F Bernabé). Fragment A, on the other hand, which, as we learn from a running heading, comes from Book 23 of the poem, offers a substantial portion of an almost unparalleled mythical narrative, featuring a dialogue between Persephone and Aphrodite in the Underworld regarding the destiny of a divine child. In this article I will argue that this story belongs to a portion close to the end of the Orphic Rhapsodies, where, as recoverable from previously neglected or not properly interpreted Neoplatonic sources, Adonis played an important role as one of the final instantiations of Dionysus.

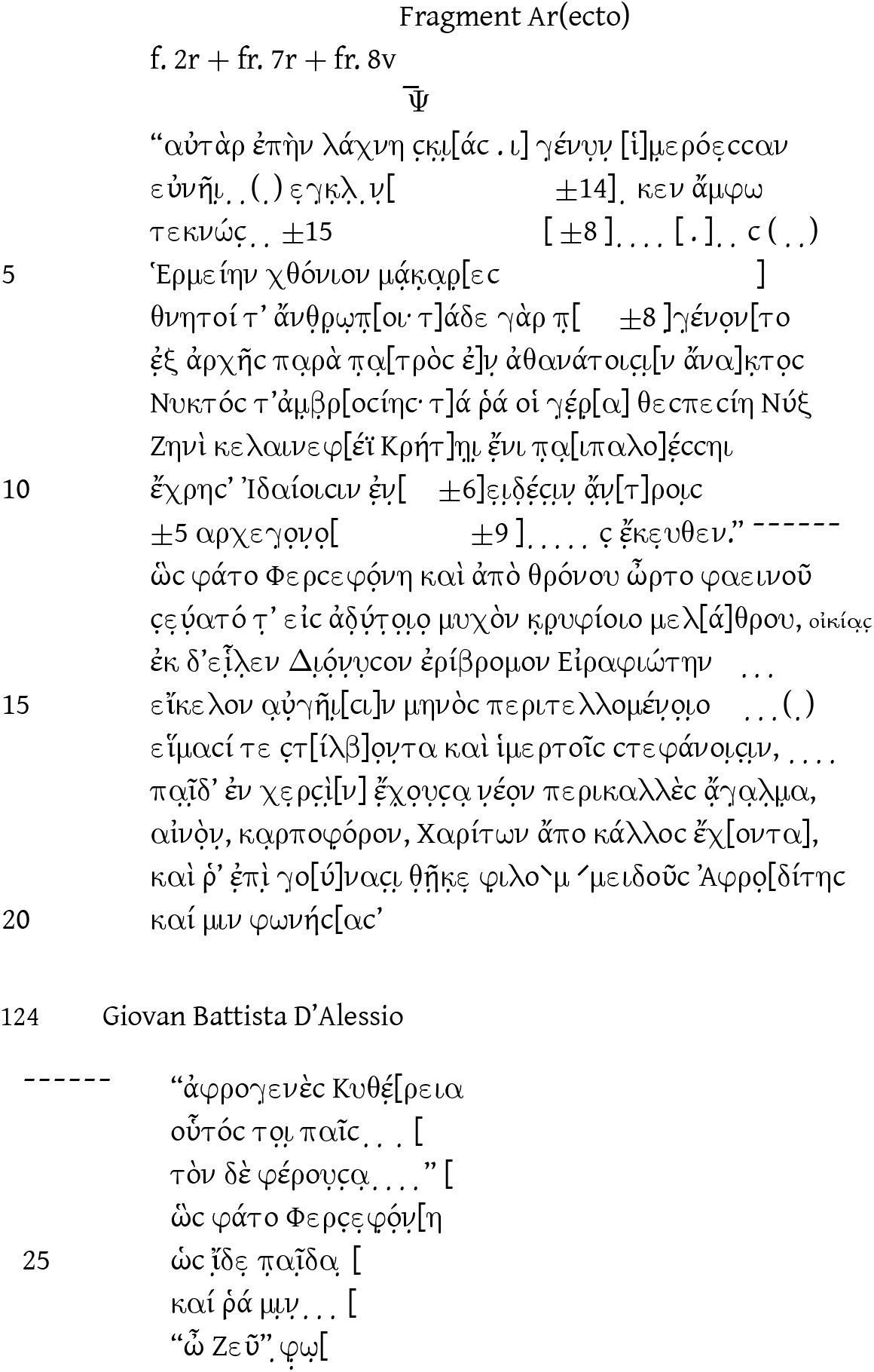

Below I provide an updated, consolidated, and revised text of fragment A, with a critical apparatus and a working translation.Footnote 2

1 An interim revised text

GBD1 = D’Alessio (Reference D’Alessio2022); Rossetto= Rossetto (Reference Rossetto2021); RP= Rossetto/Pontani in Rossetto and others (Reference Rossetto2022) (= ¥); GBD2= D’Alessio 2022 workshop, Naples;Footnote 3 GBD3 = D’Alessio 2023/4 (further proposals following the Reference D’Alessio2022 workshop)

2 GBD1 ϲ̣κ̣ι̣[άϲηι: pot. q. ἐ̣ρ̣έ̣[φηι RP, Prauscello ap. GBD1, sed etiam ϲ̣κ̣ι̣[άϲαι possis (ut in oratione obliqua)

3 GBD1 εὐνῆι̣ ̣ pot. q. εὐνήν̣ RP? deinde fort. ε̣γ̣κ̣λ̣ ̣ν̣, unde de forma verbi ἐγκλίνω dubitanter cogitaverim, sed vestigia valde incerta

4 τεκνωϲ de ϲ vix dubitandum: ulteriora vestigia incerta sed αι̣ supra lineam (fort. etiam subter lineam?): εἰϲ]ό̣κεν (Magnelli ap. ¥) ἄμφω / τεκνώϲη(ϲ)τ(ε) correctum in τεκνώϲαι(ϲ)τ(ε)? GBD3, quod, nisi elisum erat, contra Meyeri legem primam fuit, ut in v. 17 (Magnelli ap. ¥ 10)Footnote 4 in fine ]ο̣υ̣ϲιν̣ GBD1, sed fort. pot. ]τ̣ ̣ϲ ̣ ̣ ; ]τιϲ RP (unde παράκοι]τιϲ Ucciardello); in fine dubium utrum an vestigia duarum litterarum dispicenda sint. καλέϲουϲιν vel simm. hic supplendum expectaveris: in fine v. igitur fort. π̣ά̣[ν]τ̣ε̣ϲ GBD3 quod in vestigia bene quadrat (e.g καλέϲουϲι δὲ πάντεϲ?)

5 μά̣κ̣α̣ρ̣[εϲ (vestigia ulteriora dispexit GBD2) e.g. θ ε ο ὶ α ἰὲν ἐόντεϲ GBD1 6 ἄνθ̣ρ̣ω̣π̣[οι (vestigia ulteriora dispexit GBD3) [. . . . . . . ./(ἐ)]γ̣έ̣νοντ̣[ο GBD1 e.g. γάρ π[οτε δῆλα], π[ερίφαντα] ?? GBD1 /GBD2 π[ερίπυϲτα] Pontani, Ucciardello Workshop 2022, π[ερίδηλα] Ucciardello per litt. coll. Hesych. π 1630

7 πα̣ρὰ π̣α̣[τρὸϲ (Thomas ap. ¥) ἐ]ν̣ ἀθανάτοιϲ̣ι̣[ν ἄνα]κ̣το̣ϲ legit et supplevit GBD2

9 π̣α̣[ιπαλο]έ̣ccηι GBD1, RP

10 ]ε̣ι̣δ̣έ̣ϲ̣ι̣ν̣ (ι̣δ̣έ̣ϲ̣ι̣ν̣ dispexerunt RP), unde ἐν [ἠερο]ειδέϲιν De Stefani, Thomas ap. ¥, ἐν[ὶ ϲκιο]ειδέϲιν Magnelli ap. ¥, ἄντ]ροι̣c GBD1, RP (ἄ̣ν̣[τ]ροι̣c dispexit GBD3)

11 in initio βουλὰϲ̣ leg. RP

12 Φερcεφό̣νηι cod.: correxerunt GBD1, RP

13 τ̣’ εἰϲ e correctione (e τιϲ) | εἰϲ ἀδ̣ύ̣τ̣ο̣ι̣ο̣ (vestigia minima) μυχὸν dispexit et legit GBD3 (εἰϲ ἄδ̣υ̣τ̣ο̣ν̣ [μύχατον] GBD1) οἰκία̣ϲ̣ notam in margine dextro dispexit GBD3 (glossa ad μελ[ά]θρου, ut in schol.min. Hom. in PAphrodLit II Fo 1 ad Il. 2.414 [Ucciardello per litt.], cf. etiam sch. D ad Il. 9.636, Hesych. μ 623, 624)

14 ἐκ δ’εἷ̣λ̣εν GBD1 potissimum; in margine dextro fort. nota nunc evanida

15 εἴκελον initio fort. e correctione (ε ι addito?) ἴκελον (RP) contra metrum; in margine dextro nota nunc evanida

16 in margine dextro fort. nota nunc evanida

17 οντα legi non potest; ἔ̣χ̣ο̣υ̣ϲ̣α̣ pot. q. ἑλ̣οῦϲα (ἑλ]οῦϲα RP); cf. hy. Hom. Dem. 187 παῖδ’ ὑπὸ κόλπῳ ἔχουϲα νέον θάλοϲ

18 αἰνόν (Rossetto) non αἰνῶϲ (dubitanter GBD1)

19 fort. γ̣ο[ύ]ναϲ̣᾽ἔ̣θ̣ῆ̣κ̣ε ̣ scriptum erat (RP) sed γούναϲι θῆκε debuerat (GBD1)

22 οὗτόc τοι (RP) παῖϲ GBD3 (contra legem Hilbergi, ut in Br 5 et saepius in Rhapsodiis: cf. Valentino [above, n. 4] 28 f., nisi e.g. ἐϲτι sequebatur)

23 τὸν δὲ φέρουϲα fere Magnelli, Santamaría ap. ¥

25 ὡc ἴ̣δε̣ π̣αῖ̣δα sic fere RP

26 καί ῥά μιν GBD1, De Stefani, Santamaría ap. ¥ (8 x Q.S., sed cf. iam Pind. Ol. 7.59, Pyth. 3.45); καί ῥά μιν … προϲέειπε in fine v. GBD1, ut in Q.S. 7.293, 12.286. In fine fort. α̣π̣τ̣[? (ἁ̣π̣τ̣[ομένη cum gen. insequente?) sed vestigia valde incerta

27 ὦ Ζεῦ ̣ ( ̣) φ ̣ ̣[: ̣ ( ̣) epsilon supra lineam

Translation, modified from D’Alessio (Reference D’Alessio2022):

Book 23 (heading on upper margin)

(Persephone speaking) ‘But when down (will shade) his desirable cheek, (…) in (?) sexual union (…) (?) (…) both (…) will beget (…) (whom) all (?) the blessed (gods who live forever) and mortal men (will call?) Hermes of the Underworld. For from the beginning these things were (made known?) from the father, lord among the immortals, and eternal Night. For prophetic Night predicted these (privileges) for him to Zeus black-in-clouds in rugged Crete in the (misty) caves of Ida (…) primal (…) hid.’ Thus spoke Persephone and arose from her splendid throne and rushed in the innermost chamber of her secret inaccessible abode, and took out of it loud-roaring Dionysus, Eiraphiotes, similar to the rays of the rising Moon, gleaming in his garments and his lovely garlands, bringing in her hands a young child, a splendid ornament, terrible, fruit-bearing, having beauty from the Charites, and placed him on the knees of laughter-loving Aphrodite. And addressing her (she said) ‘Kythereia, born from foam, (…) this child (…) and carrying him (…).’ Thus spoke Persephone (…) as soon as she saw the child (…) and then (addressing) him (?) (spoke Aphrodite). ‘O Zeus (…)’

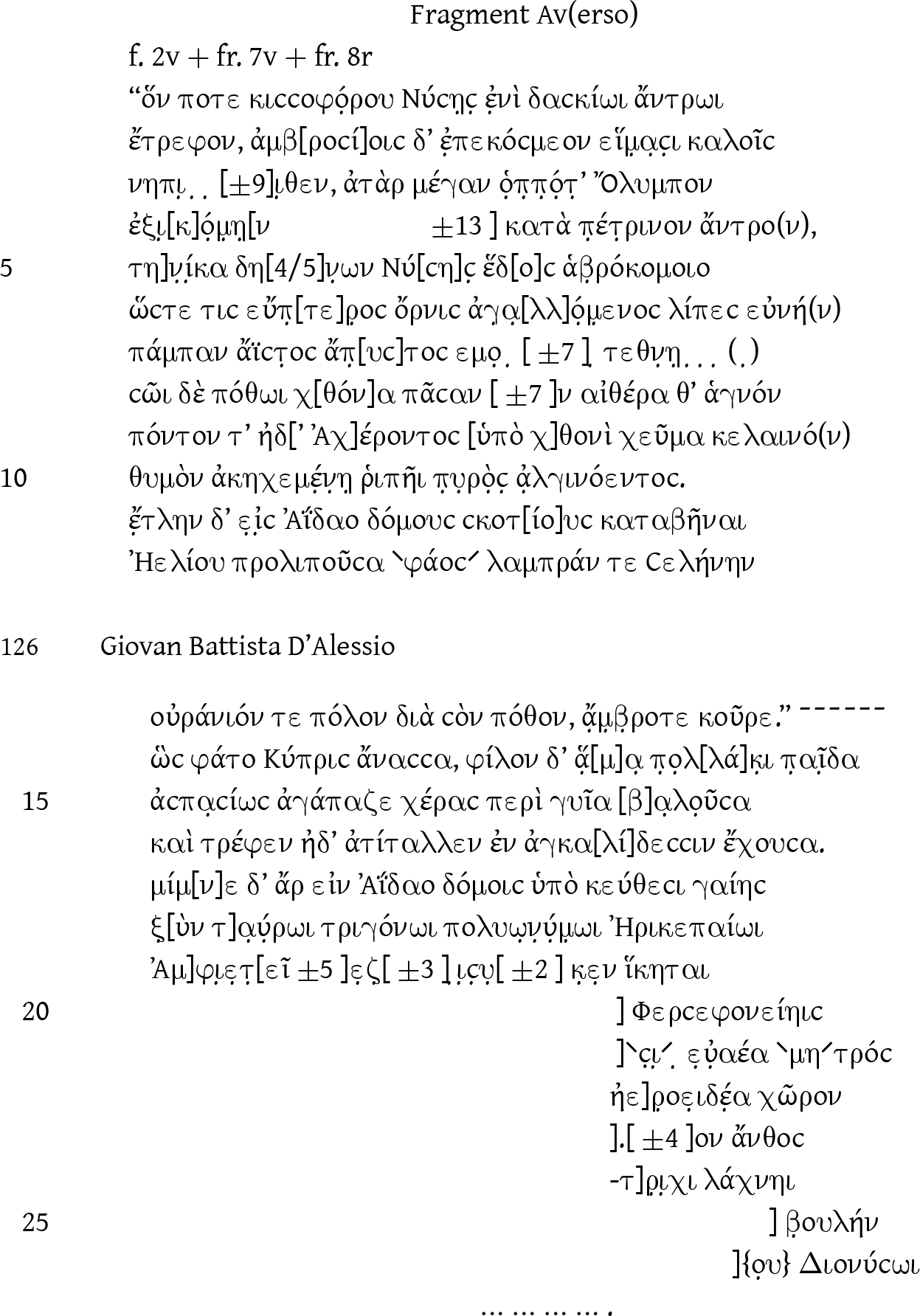

2 δ’ ἐ̣ inter δ’ et ἐ̣ vestigium (non elisionis signum, ut vid.)

3 νήπιον Rossetto νηπίαχον De Stefani, Herrero ap. ¥; ]ι̣ pot. quam η (¥), vel υ (GBD1): tum (νήπιον) ὄντα/ νηπιάχοντα (GBD1) πάροιθεν (πάροιθεν Ucciardello ap. GBD1) vel (νηπίαχον) προπάροιθεν possis GBD3; [ὁππότ’], vel [εὖτ᾽ἐϲ] GBD1, sed ὁ̣π̣π̣ό̣τ̣’ in vestigia congruere vidit GBD3

4 ἐξι̣[κ]ό̣μ̣η̣[ν GBD1, Santamaría, Thomas ap ¥ deinde e.g. μοῦνοϲ δ᾽ ἔπελεϲ GBD1

5 τη]νί̣κα GBD1 (vestigia non quadrant in αὐ]τ̣ίκα GBD1) δὴ GBD1 pot. q. τη]νικάδ᾽ η[, tum [ϲὺ λι]πών GBD1 vel [προλι]πών Pontani, sed cf. λίπεc in v. 6, et ]ν̣ pot.q. ]π̣ legendum videtur? θύ]νων (GBD3) brevius spatio; an τηνίκα δη̣[λαί]ν̣ων GBD3 cl. Hsch. s.v. δηλαίνουϲι· παίζουϲι? sed fort. etiam hoc brevius spatio: non liquet; Νύ[ϲη]ϲ̣ Ucciardello ap. GBD1, Lefteratou, Magnelli, Thomas ap. ¥ ἕδ[ο]ϲ RP, Ucciardello ap.GBD1

6 εὔπ̣[τε]ρ̣οϲ recte RP (non εὔ[τρο]φ̣οϲ, ut GBD1 et Herrero ap. ¥: vestigia certe in ρ, non φ, ut in ed. princ., quadrant) sed fort. brevius spatio? ἀγ̣α̣[λλ]ό̣μ̣ενoc GBD1 et De Stefani, Palermo-Rossi, Thomas ap. ¥

7 ἐμοί GBD1, RP; in fine -τ’ ἔθηκαϲ RP at dubium an τεθν̣η̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ pot. legendum videatur (GBD1, dubit. τεθνηυια ̣legit GBD3): non liquet

8 χ[θόν]α πᾶϲαν De Stefani, Santamaría, Thomas ap. ¥, Kayachev, deinde e.g. [ἐπέδραμο]ν De Stefani ap. ¥

10 ἀκηχεμέ̣ν̣η̣ ῥιπῆι (R. Nicolò) πυρὸϲ (GBD3) ἀ̣λγινόεντοc

14 ἅ[μα] GBD1, De Stefani ap. ¥, pot. q. ἄ[ρα] RP

12 δόμουϲ in linea φάοϲ supra lineam

18 in initio fort. ξ̣[ legit GBD3 ξὺν] Magnelli ap. ¥ inde τ]α̣ύ̣ρωι GBD1 pot. q. κο]ύρωι (Magnelli ap. ¥, noluerat GBD1)

19 Ἀμ]φι̣ε̣τ̣[εῖ GBD2; in fine ] κ̣ε̣ν possis GBD3

20 vel pot. Φερcεφονείη{ι}c (Santamaría ap. ¥); adjectivum tantum in AP 7.483.3 (Φερϲεφονείαϲ Plan.)

21 λ̣ε̣α Rossetto Reference Rossetto2021: δ̣ε̣α GBD1 (qui temptavit μήδεα), νηλέα Magnelli ap. ¥, sed potius υ̣α̣εα legendum (inde fort. εὐαέα) GBD3 πατρόϲ in linea μητρόϲ supra lineam

22 ]ρ̣οε̣ϊδε̣α dispexit GBD1 (potissimum ἠε]ροειδέα)

24 -τ]ρ̣ι̣χι dispexit GBD1 (e.g. εὔ]τριχι, ξανθό]τριχι simm.)

25 ] β̣ουλήν GBD2

26]{ο̣υ} GBD1

Translation, modified from D’Alessio (Reference D’Alessio2022):

(Aphrodite speaking) ‘(the child) whom I once raised in the darkly shaded cave of ivy-bearing Nysa, and adorned with immortal beautiful garments, still an infant (…); but when I went to great Olympus (…) in the rocky cave (…) then (…) the abode of fair-haired Nysa (…) you, (rejoicing) as a well-winged bird left your nest, without being heard and seen at all, and to me (…). And for my desire for you I (run across) the whole earth and the pure ether, and the sea, and the black stream of Acheron under the earth, aching in my heart for the blow of a painful fire. And I suffered to descend in the dark house of Hades, abandoning the light of the Sun and the bright Moon, and the celestial pole, moved by my desire for you, immortal boy.’ Thus spoke Lady Kypris and at once gladly fondled the child many times, embracing his body with her hands, and tended and cherished him, holding him in her arms. And she remained in the house of Hades under the depths of the earth, together with the (Bull), thrice born Erikepaios by the many names, the One of the Alternate Year (…) may come (?) (…) of Persephone (…) airy (?) of the mother (…) misty place (…) flower (…) -hair (?) down (…) to Dionysus.

2 The child Dionysus/Adonis in the Underworld

The first part of the story is related by Aphrodite in a flashback speech addressed to the child himself. Her speech must have started in the last preserved lines of the recto and included the first thirteen lines of the verso. Aphrodite tells that she had been rearing the child in the cave of Nysa. During an absence of the goddess on Mt Olympus, the child disappears. The goddess, longing for him, explores all the realms of the world and eventually arrives in the house of Persephone. This brings us almost to the time of the narration itself. In a speech whose last part occupies the first nine lines of the recto Persephone relates an oracle about the child, communicated to Zeus by the goddess Night on Mt Idas (a characteristic feature of Orphic theogonic poems). This apparently had to do with the child’s destiny after he reaches puberty and generates an individual whom gods and mortal will call Hermes of the Underworld. After her speech, Persephone rushes into the innermost chamber of her house, fetches a splendid and lavishly dressed little child, and places him on Aphrodite’s knees.Footnote 5 At this point she addresses the goddess in a very fragmentary three-line speech (recto 21–23); Aphrodite then delivers her speech, at the end of which (on the verso side of the fragment) we learn that she remains with the child in the Underworld .

This is the timeline of the narrated events: 1) in the remote past, Night delivers an oracle to Zeus on Mt Idas regarding the future of the child, apparently including the fact that he will beget Hermes Chthonios (recto 2–10, reported by Persephone); 2) in the near past, Aphrodite rears the child on Mt Nysa (verso 1–4, reported by Aphrodite); 3) Aphrodite goes to Mt Olympus and the child disappears (verso 5–7, reported by Aphrodite); 4) Aphrodite looks for the child everywhere, and eventually descends into the Underworld (verso 8–13, reported by Aphrodite); 5) in the present of the narration, Aphrodite meets Persephone, who tells her of Night’s prophecy; 6) Persephone fetches the child from the innermost chamber of her abode and places him on Aphrodite’s knees (recto 12–19); 7) Aphrodite embraces and addresses the child (recto 25–27, verso 14–16); 8) Aphrodite remains with the child in the Underworld (verso 17–26), fulfilling Night’s prophecy as in 1.

The narrator identifies the child as Διόνυσος ἐρίβρομος Εἰραφιώτηϲ (14b recto, an hemistich that occurs also in Dionysius Periegetes, 576). In the verso he is described (always by the narrator) with other epithets (partly supplemented) that are usually applied to Dionysus: Bull (?), Thrice-born, Erikepaios, Amphietes (18–19 verso), and, apparently, again as Dionysus at v. 26.

There are no extant parallels for such a story regarding Aphrodite, Persephone, and Dionysus. As I have already shown in an earlier contribution, however, some of its features can be related to versions, attested by a small minority of sources, of the story of Aphrodite, Persephone, and Adonis.Footnote 6 In its best-known variants Adonis is the offspring of the incestuous union between Myrrha and her father, King Kinyras of Cyprus. He is born out of the trunk of the tree into which her mother had been transformed; he is reared by Aphrodite and becomes the lover of the goddess. Once a youth, he is killed by a boar while hunting. After his death, he becomes the object of a dispute between Aphrodite and Persephone, and, following an arbitration, ends up spending different portions of the year with the two goddesses. Only in one source the dispute involves not the dead youth but an infant. In the mythological handbook that went under the name of Apollodorus (Ps.-Apollodorus’s Library), we learn that Aphrodite was struck by the beauty of Myrrha’s baby child and entrusted him to Persephone, who later refused to give him back:

Ps.-Apollodorus, Library 3.183–5

Ἡσίοδος (fr. 139 M. W.= 107 Most) δὲ αὐτὸν Φοίνικος καὶ Ἀλφεσιβοίας λέγει, Πανύασσις (fr. 27 Bernabé) δέ φησι Θείαντος βασιλέως Ἀσσυρίων, ὃς ἔσχε θυγατέρα Σμύρναν. αὕτη κατὰ μῆνιν Ἀφροδίτης (οὐ γὰρ αὐτὴν ἐτίμα) ἴσχει τοῦ πατρὸς ἔρωτα, καὶ συνεργὸν λαβοῦσα τὴν τροφὸν (184) ἀγνοοῦντι τῷ πατρὶ νύκτας δώδεκα συνευνάσθη. ὁ δὲ ὡς ᾔσθετο, σπασάμενος <τὸ> ξίφος ἐδίωκεν αὐτήν·ἡ δὲ περικαταλαμβανομένη θεοῖς ηὔξατο ἀφανὴς γενέσθαι θεοὶ δὲ κατοικτείραντες αὐτὴν εἰς δένδρον μετήλλαξαν ὃ καλοῦσι σμύρναν. δεκαμηνιαίῳ δὲ ὕστερον χρόνῳ τοῦ δένδρου ῥαγέντος γεννηθῆναι τὸν λεγόμενον Ἄδωνιν, ὃν Ἀφροδίτη διὰ κάλλος ἔτι νήπιον κρύφα θεῶν (185) εἰς λάρνακα κρύψασα Περσεφόνῃ παρίστατο. ἐκείνη δὲ ὡς ἐθεάσατο, οὐκ ἀπεδίδου. κρίσεως δὲ ἐπὶ Διὸς γενομένης εἰς τρεῖς μοίρας διῃρέθη ὁ ἐνιαυτός, καὶ μία μὲν παρ’ ἑαυτῷ μένειν τὸν Ἄδωνιν, μίαν δὲ παρὰ Περσεφόνῃ προσέταξε, τὴν δὲ ἑτέραν παρ’ Ἀφροδίτῃ· ὁ δὲ Ἄδωνις ταύτῃ προσένειμε καὶ τὴν ἰδίαν μοῖραν. ὕστερον δὲ θηρεύων Ἄδωνις ὑπὸ συὸς πληγεὶς ἀπέθανε.

Hesiod (fr. 139 M. W.= 107 Most) says that he (sc. Adonis) was the son of Phoenix and Alphesiboea, Panyassis (fr. 27 Bernabé) that he was the son of Theias, King of the Assyrians, who had Smyrna as his daughter. This daughter, due to the wrath of Aphrodite (as she did not pay homage to her), conceived a passion for her father and having taken her nurse as an accomplice slept for twelve nights with her father, while he was ignorant of her identity. But when he realized it, he drew his sword and rushed against her. When she was about to be caught, she prayed to the gods to make her invisible. The gods, moved to piety, changed her into the tree called smyrna (myrrh). Nine months later the tree burst apart, and he who is called Adonis was born. Aphrodite, for his beauty, when he was still an infant, in secret from the gods, entrusted him to Persephone hiding him in a chest. But when Persephone gazed him, she did not want to give him back. An arbitration took place under the judgment of Zeus, and the year was divided into three parts: he decreed that Adonis should spend one part by himself, one by Persephone and the other by Aphrodite. But Adonis gave his part too to her. Later on, Adonis died while hunting, hurt by a wild boar.

The last genealogical authority quoted in this handbook before reporting the whole story is Panyassis a fifth-century epic poet, who might be also the source for this particular detail (cf. fragment 27 Bernabé), even if this remains very uncertain.Footnote 7 No such story is told in any preserved text about Dionysus, but there is visual evidence indicating that this version of the Adonis story was current in the first half of the fourth century BCE.Footnote 8 As argued in D’Alessio (Reference D’Alessio2022), already in the first half of the fifth century BCE the Locrian pinakes very strongly suggest that a similar story, involving Persephone, a richly adorned child taken from a chest, and another female figure standing in front of them, was part of the repertoire of images accompanying the ritual activities in one of the most important religious sanctuary of Southern Italy dedicated to Persephone.Footnote 9

There is evidence, moreover, that in some contexts Dionysus and Adonis had been assimilated. The passages most relevant to our fragments are provided by the Orphic Hymns. In the hymn to Adonis (56), Adonis, said to have been born in Persephone’s bed, is designated with epithets characteristic of Dionysus (Eubouleus, Two-horned). In the hymn to Dionysus ‘of the Cradle’, Liknites (46), the god is said to be a scion of the Nymphs and Aphrodite and to have been brought to Persephone and reared by her according to the will of Zeus. Only one other passage has been identified so far placing the story of Aphrodite and Adonis within an explicitly Orphic context. It is [Orph.] A. 30, where, within the list of the poetic themes treated by Orpheus himself, we find the mention of αἰπεινήν τε Κύπρον καὶ Ἀδωναίην Ἀφροδίτην (‘steep Cyprus and Adonaean Aphrodite’), but with no clues about which version of the story might have been alluded to. In D’Alessio (Reference D’Alessio2022) I have argued that various elements in the Orphic Hymns seem to presuppose the narrative of the new palimpsest fragment, or a story close to it.Footnote 10 This gives us, however, little help to understand what might have been the role of the episode within the general structure of the Rhapsodies, if that was, indeed, as I believe, the poem represented in the Sinai palimpsest. More generally, we would seem to have almost no information at all on its content for the phase that chronologically followed the dismemberment of Dionysus and the birth of a new Dionysus. In the next part of this paper, I argue that previously neglected pieces of evidence from Neoplatonic sources, along with the new palimpsest fragment, can illuminate the important role of the Adonis episode near the end of the Orphic theogonic poem.

3 Adonis: the Third DemiurgeFootnote 11

The first passage relevant for us is from the Second Book of Proclus’ Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus (1.446 Diehl, 2.349 van Riel). This comes from a section dealing with Timaeus 31a 3–4, on the unicity of the heaven as created. According to Proclus, the heaven must be ‘one, if the work of the demiurge is done according to the Paradigm’ (ἕνα, εἴπερ κατὰ τὸ παράδειγμα δεδημιουργημένος ἔσται). The problem Proclus faces is that of explaining the relationship between the uniqueness of the cosmos and the actual multiplicity it contains. This is the final part of the section of doxography devoted to the passage, which Proclus attributes to his teacher Syrianus and to himself (cf. 1.441 Diehl, 2.343 van Riel).

ἔστι δὲ καὶ ἄλλως ἐπιβάλλειν τῇ λύσει τῶν ζητουμένων· τῆς γὰρ δημιουργίας, ἣ μέν ἐστιν ὅλη καὶ μία καὶ ἀμέριστος, ἣ δὲ μερικὴ καὶ πεπληϑυσμένη καὶ προϊοῦσα κατὰ μερισμόν, ἣ δὲ οὐ μόνον οὖσα μεριστή, καϑάπερ ἡ πρὸ αὐτῆς, ἀλλὰ καὶ τῶν γενητῶν ἐφαπτομένη καὶ τῶν ἐν τούτοις εἰδῶν. καὶ ἔχεις τῶν τριῶν τούτων δημιουργιῶν καθά<περ> παρ᾽ αὐτῷ τὰς μονάδας, Footnote 12 τὴν Δίιον, τὴν Διονυσιακήν, τὴν ᾿Αδωνιακήν,Footnote 13 αἷς καὶ τὰς τρεῖς πολιτείας συνδιεῖλεν, ὡς ἐν ἄλλοις εἴπομεν.

It is possible to go about answering these questions in yet another way. One creation [the first] is whole, single, undivided, another one [the second] is particular and pluralized and proceeds by means of division, yet another one [the third] is not only divided, like the one that precedes it, but also deals with generated things and the species [which occur] in them. And you can find the monads of these three creations in the same way as in him [Plato]. They are that of Zeus, that of Dionysus, and that of Adonis, by means of which he [Plato] also distinguished the three polities, as we have said elsewhere’ (translation after Runia and Share (Reference Runia and Share2008) 336, modified).

Proclus refers here to a previous treatment of the topic, which is usually thought to be the passage of Essay 13 of his Commentary to Plato’s Republic. Here, though, the notion of the three demiurges is taken for granted, without further explanations:

Proclus, Commentary to the Republic (Chapter 11 of Essay 13) 2.8.13 ff. Kroll

Τῶν τριῶν πολιτειῶν εἰς τὰς τρεῖς δημιουργίας ἀναφερομένων, εἰς τὴν Δίιον, εἰς τὴν Διονυσιακήν, εἰς τὴν Ἀδωνιακήν (πᾶς γὰρ πολιτικὸς ἀπεικονίζεσθαι βούλεταί τινα δημιουργόν, ὁ μὲν πάντα κοινὰ ποιῶν τὸν τὰ ὅλα ποιοῦντα, ὁ δὲ νέμων καὶ διαιρῶν τὸν διελόντα ἀπὸ τῶν ὅλων τὰ μέρη, ὁ δὲ ἐπανορθῶν τὸ διάστροφον εἶδος τὸν τὰ γιγνόμενα καὶ φθειρόμενα ἀνυφαίνοντα) …

The three types of constitutionFootnote 14 are related to the three demiurgies of Zeus, Dionysus, and Adonis. For every statesman wishes to imitate some Demiurge: the statesman who establishes all property in common wishes to imitate the Demiurge of the universe, the one who apportions and divides wishes to imitate the Demiurge who divides parts from wholes, and the one who sets right the twisted form [of government] wishes to imitate the Demiurge who weaves anew what comes into being and perishes (translation Baltzly, Finamore and Miles (Reference Baltzly, Finamore and Miles2022) 210, slightly modified).Footnote 15

It is likely that there was a fuller treatment elsewhere in a work now lost, which conceivably went back to Syrianus too. A clue in this direction is provided by the commentary of Hermias (which goes back to Syrianus) on the only Platonic passage where Adonis is mentioned (p. 273.25 ff. Lucarini/Moreschini, on Pl. Phdr. 276b) οὓς καὶ Ἀδώνιδος κήπους καλεῖ, ἐπειδὴ τῶν ἐν γῇ φυομένων καὶ ἀποβιωσκομένων ὁ δεσπότης Ἄδωνις ἐφέστηκε, πᾶσα δὲ ἡ γένεσις καὶ φθορὰ ἡ περὶ ἡμᾶς κήποις ἔοικε ‘which he calls also Adonis’ gardens, as Adonis is the lord in charge of what comes into life and ceases to live on earth, and the whole procession of generation and death that concerns us is similar to (these) gardens’. Plato’s text only mentions ‘Adonis’ gardens’ without making any reference to Adonis’ creative powers. Plato, indeed, contrasts Adonis’ gardens with the results of proper agriculture. The commentator, on the other hand, presents Adonis as ‘the lord of what comes into life and ceases to live on earth’. This corresponds closely to the definition of the Third Demiurge ‘who weaves anew what comes into being and perishes’ as defined in the Commentary on the Republic examined above and it is well conceivable that this definition was already in Syrianus.Footnote 16

Also in Book 1 (1.74.14–16 Diehl, 1.112 van Riel) of the Timaeus Commentary a third demiurge is mentioned but not identified. His cooperation with the second one is considered a necessity: δεῖται γὰρ ἡ ὅλη γένεσις καὶ τῶν ἐκ τοῦ ὑποχθονίου κόσμου πάντως (παντὸς coni. Tarrant) ἀναδόσεων ‘as the entire process of generation also requires on the whole germinations from the (‘whole’, with Tarrant’s conjecture) subterranean world’.Footnote 17 The image of the generation depending on what is germinated/issued forth from the subterranean world would be very appropriate to Adonis.Footnote 18

It has been noted that Proclus’ mentions of the third demiurge show interesting similarities to the way in which Iamblichus described the subunar demiurge in a fragment of his lost commentary to Plato’s Sophist (fr. 1 Dillon):Footnote 19

ἔστι γὰρ κατὰ τὸν μέγαν Ἰάμβλιχον ὁ σκοπὸς νῦν περὶ τοῦ ὑπὸ σελήνην δημιουργοῦ. οὗτος γὰρ καὶ εἰδωλοποιὸς καὶ καθαρτὴς ψυχῶν, ἐναντίων λόγων ἀεὶ χωρίζων, μεταβλητικός, καὶ ‘νέων πλουσίων ἔμμισθος θηρευτής’ (Pl. Soph. 231d3), ψυχὰς ὑποδεχόμενος πλήρεις ἀλόγων (v.l. λόγων) ἄνωθεν ἰούσας, καὶ μισθὸν λαμβάνων παρ’ αὐτῶν τὴν ζωοποιίαν τὴν κατὰ λόγον τῶν θνητῶν. οὗτος ἐνδέδεται τῷ μὴ ὄντι, τὰ ἔνυλα δημιουργῶν, καὶ τὸ ὡς ἀληθῶς ψεῦδος ἀσπαζόμενος, τὴν ὕλην· βλέπει δὲ εἰς τὸ ὄντως ὄν. οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ πολυκέφαλος, πολλὰς οὐσίας καὶ ζῳὰς προβεβλημένος, δι’ ὧν κατασκευάζει τὴν ποικιλίαν τῆς γενέσεως

the aim of this dialogue according to the great Iamblichus is the sublunar demiurge, for he is a maker of images (εἴδωλα) and a purifier of souls, always separating between contrary arguments, and a changer and a ‘paid hunter of rich young people’ (Pl. Soph. 231d3), as he receives the souls that come from above rich of irrational elements (or ‘of reasonings/rational principles’, the reading is doubtful), and takes as his reward from them the creation of life according to the principle of mortals. And he is bound with the Not-Being, since he is the demiurge of material things, and welcoming embraces what is truly falsehood, the matter, but looks toward what is really Being. And he has many heads, bringing forward many essences and lives, through which he produces the variety of generation.Footnote 20

This may indeed offer us a glimpse of the treatment of the issue before Proclus.Footnote 21

Leaving now aside the theoretical reasons that must have led to the formulation of the theory of the three demiurges, the question that interests us here is that of their connection to three gods, respectively, Zeus, Dionysus and Adonis. As we saw above, according to Proclus himself the last section of the exegesis on the Timaeus passage goes back to his teacher Syrianus. A prominent feature of Syrianus’ reading of Plato was that of establishing a harmonic interpretation (συμφωνία) that placed Plato’s text in the context of a theological tradition in which ‘sacred texts’, such as the Orphic Rhapsodies played a very important role.Footnote 22 The identification of the first two demiurges with Zeus and Dionysus does indeed very clearly reflect the sequence of the Orphic Rhapsodies, in such a way that Dionysus’ dismemberment was related to the identification of the god with the demiurge of the ‘divided’ world. The derivation of this scheme from the Rhapsodies can be taken for granted, and is explicitly acknowledge by Proclus, for example, in Book 5 of his Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus, ad Tim. 42d (3.310.29 Diehl, 5.195 van Riel):

ὅτι καὶ ἡ μονὰς αὐτῶν νέος καλεῖται θεός· τὸν γὰρ Διόνυσον οἱ θεολόγοι ταύτῃ τῇ προσηγορίᾳ κεκλήκασιν, ὃ δέ ἐστι πάσης τῆς δευτέρας δημιουργίας μονάς· ὁ γὰρ Ζεὺς βασιλέα τίθησιν αὐτὸν ἁπάντων τῶν ἐγκοσμίων θεῶν καὶ πρωτίστας αὐτῷ νέμει τιμάς,

καίπερ ἐόντι νέῳ καὶ νηπίῳ εἰλαπιναστῇ (F 299.3 Bernabé).

(they are called ‘young/new gods’ by Plato) because also their monad is called a ‘new/young god’: as the theologians (i.e., among others, the author of the Orphic poems: the following line is quoted from the Orphic Rhapsodies) have called Dionysus with this appellation, and he is the monad of the whole second demiurgy, as Zeus makes him king of all the encosmic gods and attributes to him the very first honours

even if he was young and an infant at banquet (F 299.3 Bernabé). Footnote 23

This premise leads very naturally (unavoidably, I would say) to the conclusion that the presence of Adonis in this scheme implies that he too must have played a prominent role within the general structure of this Orphic poem, even if, to my knowledge, this hypothesis has never been formulated, and no trace of Adonis appears in older and newer collections of the fragments of the Orphic Rhapsodies. Once this connection is made, the discovery of the Sinai palimpsest (with the interpretation proposed above), along with further Neoplatonic passages (to be examined below), can bring, I believe, significant light to this less-known portion of the Orphic Theogony.

4 The εἴδωλα of Dionysus

As we saw above, the hexameters of the Sinai Palimpsest present an apparent case of conflation between the figures of Dionysus and Adonis, a conflation that is otherwise attested, apart from the Orphic Hymns mentioned above, in only a handful of textual sources.Footnote 24 One of the most remarkable among these is a passage from Proclus’ Commentary on Plato’s Cratylus, Chapter 180, commenting on the section of the dialogue on the names and meanings of Aphrodite and Dionysus (406b):

Proclus’ Commentary on Plato’s Cratylus, Chapter 180 (107.11–17 Pasquali)

Ὅτι συνέταξεν τὸν ἐγκόσμιον Διόνυσον τῇ ἐγκοσμίᾳ ᾿Αφροδίτῃ διὰ τὸ ἐρᾶν αὐτοῦ καὶ εἴδωλον πλάττειν αὐτοῦ τὸν πολυτίμητον Κίλιξι καὶ Κυπρίοις Ἄδωνιν· καὶ δηλονότι τὸν τῆς ᾿Αφροδίτης τοιοῦτον ἔρωτα ἀγαϑοειδῇ καὶ προνοητικὸν ὑποληπτέον, ὡς παρὰ κρείττονος ϑεοῦ πρὸς καταδεέστερον ἐπιτελούμενον.

as he [i.e. Plato] ranked the encosmic Dionysus with the encosmic Aphrodite because she loves him and fashions an image (εἴδωλον) of him (Dionysus), [that is] Adonis, who was much honoured among the Cilicians and Cypriotes. It is clear that such a love on the part of Aphrodite should be understood as boniform and providential, because it is fulfilled from a greater god in relation to an inferior one (translation Duvick (Reference Duvick2007) 104, slightly modified).

The passage introduces a long section dealing mainly with the ways in which the two divinities were represented in the Orphic Rhapsodies (again, a very important source for the commentary as a whole). This is one of the very rare pieces of evidence of the love between Aphrodite and Dionysus.Footnote 25 Proclus says that Aphrodite fashioned an image (εἴδωλον) of Dionysus, which is identified with Adonis, object of great veneration in Cyprus and in Cilicia. This cryptic sentence has not, to my knowledge, attracted the attention it deserves. In what sense are we supposed to understand that Aphrodite fashioned an εἴδωλον of Dionysos? How is this related to her love for the god? Why is the εἴδωλον identified with Adonis?Footnote 26 I will argue that a possible answer to some of these questions comes both from the text of the Sinai Palimpsest and from other passages in Proclus and Damascius that do not seem to me to have been correctly explained so far.

In the passage of the Cratylus Commentary, Proclus makes no explicit reference to Orpheus as the source of his statement, even if the whole context is deeply imbued with quotations from the Orphic Rhapsodies. In another of his works, though, Proclus makes an unequivocal connection between Orpheus and the fashioning of εἴδωλα of Dionysus. The two passages have never, to my knowledge, been connected to each other.

In a previous section of Book 2 of his Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus (1.336.26–337 Diehl, 2.192 van Riel), on Pl., Ti. 29b1, Proclus deals with an issue closely related to the one examined above (p. 131), i.e. that of the relationship between model (the ‘Paradigm’, παράδειγμα) and image (εἰκών) in the creation of the demiurge:

εἰ δὲ εἰκόνα κέκληκεν ὃ Πλάτων τὸν κόσμον. οὐ δεῖ ϑαυμάζειν· καίτοι γὰρ κάλλιστος ὢν εἰκών ἐστι τοῦ νοητοῦ κάλλους, καὶ διὰ τῆς ὁμοιότητος ταύτης σῴζεται. καϑάπερ οὖν Ὀρφεὺς εἴδωλα πλάττει τοῦ Διονύσου τὰ τὴν γένεσιν ἐπιτροπεύοντα καὶ τὸ εἶδος ὡς ὅλον ὑποδεξάμενα τοῦ παραδείγματος. οὕτως καὶ ὁ φιλόσοφος εἰκόνα τὸν κόσμον τοῦ νοητοῦ προσεῖπεν, ὡς ἐοικότα τῷ σφετέρῳ παραδείγματι.

We should not be surprised if Plato has called the cosmos an image. For even though it is ‘most beautiful’ (29a5), it remains an image of the intelligible Beauty and its preservation depends on this similarity. Just as, therefore, Orpheus fashions (πλάττει) images (εἴδωλα) of Dionysus, which preside over the process of becoming and have received the form of the Paradigm as a whole, so the philosopher has also given the cosmos the appellation ‘image of the intelligible’ inasmuch as it resembles its own paradigm (translation: Runia and Share (Reference Runia and Share2008) 193, slightly modified).

All commentators of this passage and all editors of the Orphic fragments have connected it with the episode in the Rhapsodies in which Dionysus, before his dismemberment, sees his image reflected in the mirror given to him by the Titans (the evidence is collected in F 309 Bernabé, where our passage is also included). This was indeed a crucial moment within the general economy of the poem, as well as for its Neoplatonic reception, from as early as Plotinus. Proclus himself makes extensive use of it. There are, however, several reasons to doubt that the passage of the Timaeus Commentary quoted above can indeed be interpreted in this way. Before his dismemberment Dionysus sees only one image in the mirror, leading to the passage from unity to a dyad, not to a larger multiplicity of εἴδωλα. A passage to further multiplicity ensues only with Dionysus’s dismemberment in seven parts, but this too is hardly compatible with Proclus’s wording here and with the general context, where the images are said to be ‘in charge’ (ἐπιτροπεύοντα) of the generation of things, an expression used by Proclus and his predecessors to designate the creative action of divine beings. The seven parts can hardly be presented as an appropriate example of εἴδωλα entirely identical to their παράδειγμα: even if they preserve the god’s essence, they are not entirely identical to him. Of these parts, moreover, only one, the god’s heart, is eventually preserved in the Orphic story. It would be difficult, therefore, to see all these parts as being imagined as having the task of being in charge over the process of γένεσις. Moreover, the verb used by Proclus to describe the action, πλάσσω, is not appropriate for describing the reflection in a mirror, or the dismemberment of a body, but strongly suggests the fashioning of three-dimensional replicas of the god. Finally, it seems very unlikely that the fashioning of εἴδωλα of Dionysus here should be interpreted entirely differently from the fashioning of an εἴδωλον of Dionysus by Aphrodite in another passage from the same author. Footnote 27

All these objections disappear at once if we link this passage to the one from the Cratylus Commentary: the εἴδωλα are ‘replicas’ of the god, fashioned following his death (and, possibly, his ascension to heaven) and entrusted with the task of presiding over a different phase of the world generation. This corresponds perfectly to the case of Adonis. In the Sinai Palimpsest the figure of the immortal child, who typologically corresponds to the role of Adonis in other sources, is entirely identified with Dionysus. The reason behind this is surely that within the narrative at some stage Adonis was presented as an εἴδωλον of the god: the child is, at the same time, Dionysus and Adonis. The fact that Aphrodite is responsible for his fashioning in Proclus corresponds to the role she has in rearing the child in the new hexameters. Proclus presents the Orphic εἴδωλα of Dionysus as τὰ τὴν γένεσιν ἐπιτροπεύοντα, a role corresponding to the definition of Adonis as the third demiurge in the Neoplatonic sources that we have examined above.

There is a further passage in Proclus that, I would argue, is probably to be explained against the same background. This comes from his Essay 6 on Plato’s Republic, an extremely long treatment of the Iliadic theomachy (1.94.7 Kroll). Here Proclus argues that the involvement of the Homeric gods in struggles and fights can be explained by the fact that these gods, being the last ones in the divine chain, are particularly close to the (human) beings that are the object of their care and are therefore endowed with features and behaviours that belong to them. It is at this point that a comparison is made with the Orphic εἴδωλα of Dionysus:

Proclus, Commentary on the Republic (Essay 6) 1.94.7 Kroll

ὥσπερ δὴ καὶ Ὀρφεὺς τοῖς Διονυσιακοῖς εἰδώλοις τὰς συνθέσεις καὶ τὰς διαιρέσεις καὶ τοὺς θρήνους προσῆψεν ἀπὸ τῶν προνοουμένων ἅπαντα ταῦτα ἐκείνοις ἀναθείς

In just the same way Orpheus too connected the Dionysian images with the acts of being formed and dissolved and with funerary lamentations, attributing to those [images] all these acts that are derived from the subjects of their providential care (translation Baltzly, Finamore and Miles (Reference Baltzly, Finamore and Miles2018) 205–6).

Here too commentators and editors have linked the passage to the mirror episode. It will be clear by now, though, that this passage too must refer to the same εἴδωλα of Dionysus with which we have been dealing so far. They are the last of the series of demiurgic deities, and, just as the objects of their providential care, they are born, and die, and receive funerary lamentations. This, once again, is a description that perfectly fits the case of Adonis, whose most distinctive features were his cyclical death, and the funerary lamentations that which accompanied it.

The last and latest passage in our series helps to delineate the important role of these εἴδωλα in a more general way. It comes from the Damascius’ Commentary on Plato’s Parmenides, in a section discussing the fifth point raised by what Damascius considers as the Eighth Hypothesis. The issue discussed here is τίς ἡ ἐσκιαγραφημένη τῶν ὑποκειμένων πραγμάτων ὑπόστασις, καὶ ὀνείρασιν ἐοικυῖα· μήποτε γὰρ ταῦτα οὐ πρέπει τοῖς γιγνομένοις τε καὶ συνθέτοις ‘what is the substance of the things we have assumed, painted as a trompe-l’oeil, and similar to dreams? For this is perhaps appropriate to what comes into being and is composed.’ In dealing with the illusory nature of the sublunar world Damascius notes how the demiurges operating in this world are also presented by the ‘theologians’ (i.e., again, in the very first place Orpheus: to my knowledge, though, this passage has not been considered as a witness of the Orphic poem in current editions and scholarship) as being illusory images in themselves:

Damascius’ Commentary on Plato’s Parmenides, 317.19–20 Ruelle (on Plato, Parmenides 164b–6e)

οἱ θεολόγοι τοὺς τούτων δημιουργοὺς οὐκ εἴδωλα ἡμῖν εἰσηγοῦνται συντιθέμενά τε καὶ ἀναλυόμενα; καὶ δοκοῦντα μέν, οὐκ ὄντα δὲ ὁ Διόνυσος;

Do not the theologians introduce to us the demiurges of these things as images, which are composed and dissolved? And which seem to be, but are not Dionysus?

These are the very same εἴδωλα we found in Proclus on Republic (cf. τὰς συνθέσεις καὶ τὰς διαιρέσεις and συντιθέμενά τε καὶ ἀναλυόμενα ‘the acts of being formed and dissolved’), and they are explicitly identified as demiurges. Adonis is described by Proclus both as a demiurge and as an εἴδωλον of Dionysus. There should be no doubt, I think, that Damascius is referring also to him as one of the demiurges of our illusory mortal world.Footnote 28

5 Who were the εἴδωλα of Dionysus?

Summarising our results so far, the evidence I have gathered provides crucial elements for reconstructing a previously ignored section of the final part of the Orphic Rhapsodies. One or more of the gods (Aphrodite is mentioned as fashioning Adonis in this way) fashion εἴδωλα of Dionysus, who towards the final part of the poem play a governing role in bringing to life and regulating the level of creation that involves mortal beings. According to Proclus and Damascius we seem thus to be dealing with multiple εἴδωλα and indeed, according to Damascius, with multiple demiurges. These εἴδωλα are identical to, but, at the same time, different from Dionysus, and are themselves subject to suffering and death, as well as being the recipients of funerary lamentations. They seem to be in charge of the birth of what comes into being and dies. If Dionysus, son of Persephone, was a dying god, his death was, nonetheless, a unique event. Adonis, on the other hand, was most conspicuously subject to cyclic (mythological and ritual) death and return to life, making him particularly apt to oversee the cycle of the nature that dies and is periodically renovated. He must have been, at any rate, not the only god to appear in a similar function. In other Neoplatonic sources Adonis is associated to Dionysus himself, to Attis and to Helios. The most obvious candidate as yet another εἴδωλον at this stage would seem to be Attis, who was the object of sophisticated allegorical interpretations by Neoplatonists, conveyed and developed in the very first place in Julian’s Oration to the Mother of the Gods, and whose story (especially, but not only, in Julian’s version) presents obvious affinity with that of Adonis.Footnote 29 His presence is not attested in fragments attributed to Orpheus, but he does play a role in the prayer that introduces the Orphic Hymns (prol. 40, preceding the mention of Adonis at l. 41). In Damascius in Parm. 352 (214.4 Ruelle, F 355 B) he appears among the lower gods as the demiurge of τὸ γενητόν (‘the world generated’) having obtained his place in the Moon, together with Adonis, as mentioned ἐν ἀπορρήτοις (‘in secret tales’) along with ‘many gods by Orpheus and the theurgists’. In Proclus’ Hymn to the Sun (1.24–6) both are identified with Helios (hailed also as father of Dionysus):

A further problem, which the present state of our evidence does not allow us to solve so far, is that of the relationship between the Dionysus born of Semele and the εἴδωλα. As a matter of fact, sources regarding the treatment of this divine figure in the Orphic Theogonies are exceedingly scanty, and this is certainly an issue deserving further investigation. Was he also one of them? Or should we imagine that he had a privileged position compared to his cyclically dying ‘images’? The fact that the εἴδωλα are described as being ‘composed and dissolved’ suggests that the son of Semele was not one of them, since, differently from the son of Persephone, in the standard versions he does not experience death. This leads to a further unsolved issue: is the child featured in Persephone’s realm in the new palimpsest the son of Semele, or is he already one of the εἴδωλα, who ‘seem to be, but are not Dionysus’?

6 What were the εἴδωλα of Dionysus?

It is difficult, furthermore, at this stage and with the available evidence, to establish in what sense should we understand the relationship between Dionysus and his εἴδωλα. The question is made more complex by the fact that in the long (and for large stretches of time practically undocumented) life of the Orphic Theogony between the fifth century BC and our Neoplatonic sources the concept underlying this relationship might well have evolved and changed. As I have just stressed, moreover, in our sources it is not clear whether the εἴδωλα should be taken to be images of the first Dionysus, son of Zeus and Persephone, or of the second one, born by Semele. As a provisional approach, I suggest that we look at two different, but not necessarily mutually exclusive (especially within a diachronic perspective), conceptual models

The first is that of the representation of the final destiny of divine ‘mortal’ figures. The case of the fate of Heracles, as famously represented in the Nekyia in Odyssey 11, might have been a productive model. Just as Dionysus, Heracles experiences both death and apotheosis. In his vision of the heroes of the past, Odysseus describes his meeting with Heracles in the Underworld, introducing it with these lines (Hom. Od. 11.601–4):

The scholia on line 604 inform us of an interpolation by Onomacritus: τοῦτον ὑπὸ Ὀνομακρίτου ἐμπεποιῆσθαί φασιν. ἠθέτηται δέ (‘this (line?) they say was inserted by Onomacritus, and is athetized’). Even if this has been a subject of debate, there is a reasonable consensus that the interpolation attributed to Onomacritus did not involve only v. 604 (which is identical to Hes. Theog. 952 and is omitted in part of the manuscript tradition, but has no impact on the content), but (also) the sequence of vv. 602–604.Footnote 30 Archaic Greek epic and lyric poetry know several cases of gods fashioning εἴδωλα of other gods and of human beings. The passage in Odyssey 11 would offer a potentially very interesting, if obviously, partial parallel for the case of Dionysus. With the transmitted text (said to be the result of Onomacritus’ interpolation) Heracles enjoyed an apotheosis, becoming an established god: his εἴδωλον, though, remained in the Underworld. The case of Dionysus in the Orphic poem would be somewhat similar. Proclus’ passage could be taken to imply that in his case too an εἴδωλον was fashioned, which, differently from Heracles’ εἴδωλον, would spend only part of his cyclic life in the Underworld. The fact that this passage was linked in antiquity to the activity of Onomacritus, who was famously thought to be behind some of the production of Orphic poetry in the late Archaic period (cf. T 2–5 and F 4 D’Agostino, 1110–11, 1113–15 T Bernabé), is particularly interesting in providing a parallel for our ‘Orphic’ poem.

In early literature εἴδωλα usually carry, at least partly, negative connotations of unsubstantiality, as it seems apparent also in the Odyssey interpolation, but this was not always the case already in the fifth century. This is particularly clear in the formulation of Pind. fr. 131b S. M.:

We cannot dwell here on the complex interpretation of these lines: suffice it to say that they share an approach to the conception of the soul and its destiny before and after death particularly close to the notions attributed to archaic Orphism, and later developed in the Platonic tradition.Footnote 31 Against this background, the notion of the εἴδωλα of Dionysus could conceivably acquire (partly) positive connotations.

A second model that must have played a role in the development of this remarkable concept was, I would suggest, based on the overlap between Dionysus and Osiris perceived from at least the fifth century BC (as early as Hecataeus and Herodotus: cf. Hdt. 2.144 = Hecataeus F 300 BNJ 2),Footnote 32 and particularly lively until late antiquity. By the Hellenistic period we find the notion that after Osiris was dismembered Isis (often equated to Aphrodite) produced out of his limbs a number of anthropomorphic replicas of the god:

Diod. Sic. 1.21.5 τὴν δ’ οὖν Ἶσιν πάντα τὰ μέρη τοῦ σώματος πλὴν τῶν αἰδοίων ἀνευρεῖν· βουλομένην δὲ τὴν τἀνδρὸς ταφὴν ἄδηλον ποιῆσαι καὶ τιμωμένην παρὰ πᾶσι τοῖς τὴν Αἴγυπτον κατοικοῦσι, συντελέσαι τὸ δόξαν τοιῷδέ τινι τρόπῳ. ἑκάστῳ τῶν μερῶν περιπλάσαι λέγουσιν αὐτὴν τύπον ἀνθρωποειδῆ, παραπλήσιον Ὀσίριδι τὸ μέγεθος, ἐξ ἀρωμάτων καὶ κηροῦ· εἰσκαλεσαμένην δὲ κατὰ γένη τῶν ἱερέων ἐξορκίσαι πάντας μηδενὶ δηλώσειν τὴν δοθησομένην αὐτοῖς πίστιν, κατ’ ἰδίαν δ’ ἑκάστοις εἰπεῖν ὅτι μόνοις ἐκείνοις παρατίθεται τὴν τοῦ σώματος ταφήν.

Isis found all the limbs of his (i.e. Osiris’) body, apart from the pudenda. Since she wished to keep the burial-place of her husband of uncertain identification, and yet to be the object of honour by the inhabitants of Egypt, she managed to accomplish her decision in the following way. They say that around each of his limbs out of aromatic herbs and wax she fashioned an image in human form, similar to Osiris in size. Having summoned all the priests divided according to their families she had them to take an oath not to reveal to anyone what she would entrust to them, and separately told each one of them that they were the only custodians of the burial.

According to Diod. Sic. 4.6.4, one of these replicas was the god Priapus, who as we saw above,Footnote 33 in some Greek sources was seen as the offspring of Aphrodite and Dionysus, very much as Adonis (and would be a possible candidate as one of the Orphic εἴδωλα, along with Adonis himself and with Attis):Footnote 34

οἱ δ’ Αἰγύπτιοι περὶ τοῦ Πριάπου μυθολογοῦντές φασι τὸ παλαιὸν τοὺς Τιτᾶνας ἐπιβουλεύσαντας Ὀσίριδι τοῦτον μὲν ἀνελεῖν, τὸ δὲ σῶμα αὐτοῦ διελόντας εἰς ἴσας μερίδας ἑαυτοῖς καὶ λαβόντας ἀπενεγκεῖν ἐκ τῆς οἰκείας λαθραίως, μόνον δὲ τὸ αἰδοῖον εἰς τὸν ποταμὸν ῥῖψαι διὰ τὸ μηδένα βούλεσθαι τοῦτο ἀνελέσθαι. τὴν δὲ Ἶσιν τὸν φόνον τοῦ ἀνδρὸς ἀναζητοῦσαν, καὶ τοὺς μὲν Τιτᾶνας ἀνελοῦσαν, τὰ δὲ τοῦ σώματος μέρη περιπλάσασαν εἰς ἀνθρώπου τύπον, ταῦτα μὲν δοῦναι θάψαι τοῖς ἱερεῦσι καὶ τιμᾶν προστάξαι ὡς θεὸν τὸν Ὄσιριν, τὸ δὲ αἰδοῖον μόνον οὐ δυναμένην ἀνευρεῖν καταδεῖξαι τιμᾶν ὡς θεὸν καὶ ἀναθεῖναι κατὰ τὸ ἱερὸν ἐντεταμένον.

Regarding Priapus, the Egyptians tell a myth according to which in ancient times the Titans plotted against Osiris, killed him and dismembered his body into equal parts among them, taking them out of the house in secret. They threw in the river only his pudenda, since none of them wished to take them with him. When Isis investigated the murder of her husband and killed the Titans, she fashioned a human image around the parts of the body, gave them to the priests to bury, and ordered them to honour Osiris as a god. Not having managed to find only the genital organ, she taught to honour it as a god, and to display it in erection in the sanctuary.

A similar version is narrated in Plut. De Is. et Os. 18, where, most tellingly, the word εἴδωλα is used to indicate the god’s replicas.Footnote 35 These Greek versions have been linked to an actual Egyptian practice in the cult of Osiris, which (notably in the ritual for the Osirian festival of Khoiak, often compared to that of the Gardens of Adonis) involved the production of simulacres of the god.Footnote 36 I would suggest that the two possible models sketched above should not be necessarily considered as alternatives, but that they might, indeed, perhaps must have, interacted with each other at different chronological stages.Footnote 37

If my argument is correct, the discovery, decipherment, and interpretation of the new Sinai palimpsest, along with my new reading of the Neoplatonic sources examined above, can bring some light to the final narrative stage of the Orphic Theogony, where a crucial role was played by the last instantiations of Dionysus. These, with their cyclic mortality, opened the last era of world-history, and eventually initiated the whole cycle of life and death of human souls. Our most detailed and explicit sources are late, but many crucial parallels, as I have argued, can be traced already to the fifth century BCE (for some elements, possibly even earlier).Footnote 38 This was a story of very longue durée, which emerges only here and there from its underground course, and which changes its faces many times. I hope that this small paper may bring a contribution toward a more precise comprehension of some of its features.