One of the last events that McNamara oversaw as Secretary of Defense was the Tet Offensive, which began in January 1968. In a bid to achieve a quick battlefield victory, North Vietnamese forces staged simultaneous attacks in South Vietnam where they hoped to generate a popular uprising. None was forthcoming. Although the Tet Offensive was a military success for the United States and its ally in the South, playing as it did to their strengths, it was nevertheless a political disaster. The administration’s lack of candor undermined public faith in the US government’s ability to tell the truth. Images of the attacks on the US Embassy in Saigon undermined both General Westmoreland’s and the US government officials’ statements that the campaign had demonstrated the success of existing programs in Vietnam.

In the wake of the first attacks, Westmoreland cabled back to Washington, “We are now in a new ball game where we face a determined, highly disciplined enemy, fully mobilized to achieve a quick victory,” and requested an additional 200,000 troops to “seize the opportunity to crush him.”1 It was left to McNamara’s successor Clark Clifford to engage in the latest administration debate over troop increases. McNamara warned him to do “whatever we can to prevent the financial requirements” of the latest increase “from ruining us” in the domestic and international economic spheres.2

In July 1965, McNamara had supported troop increases on the condition that the necessary economic and political resources were enlisted. Johnson chose, however, to deploy troops but delay the costs of escalation. By 1968, this was no longer possible. Tet provoked a political crisis because the administration had not “educated the people” as it had gone “up the escalating chain,” as McNamara had recommended.3 It also marked an economic fork in the road. McNamara had hidden the financial costs of escalation by drawing down troops and resources around the world and, in so doing, depleting the military’s so-called strategic reserve. By 1968, any further troop deployment in Vietnam necessarily entailed rebuilding the reserve and thus required significant defense outlays.4

With Tet, also, the consequences of McNamara’s creative accounting became apparent. McNamara was correct in his private assessment that “there is no piece of paper – no record – showing when we changed from an advisory effort to a combat role in Vietnam.”5 The administration, and McNamara himself, had blurred that line deliberately. From a budgetary perspective, the United States never actually went to war under McNamara. It was not until 1968 that the OSD dropped its budgetary assumption that the war would end by June and instead accepted that the war could go on indefinitely. Congress was finally provided with the full anticipated costs of operations in Vietnam.6

Early on, McNamara had resisted troop deployments in Vietnam over concerns about the balance of payments deficit and the international confidence that was required to protect the dollar’s role in the international monetary system. Predictably, Tet produced jitters on the gold market. As Enthoven wrote to Clifford, “The extent of such speculation is influenced by many factors other than the size of the US deficit [including] unsettling events such as the onset of the Vietnam War, the extent to which US officials lose their confidence in the public.”7 Rusk and Rostow now also accepted that further troop deployments would have economic repercussions. Rostow worried that the crisis “could set in motion a financial and trade crisis which would undo much that we have achieved in these fields in the past twenty years and endanger the prosperity and security of the Western world.”8 By March, the London gold pool, a major component of transatlantic cooperation on international monetary issues, closed. Ultimately, economic events were as important as military considerations in determining the consequences of Tet. Economic factors, in fact, conditioned Johnson’s announcement that he would not deploy additional troops but instead move to a bombing halt with a view to a negotiated settlement.9 In other words, in the aftermath of Tet, Johnson came around to a very similar view to the one that McNamara had presented to him in 1965.

This book provides an important corrective on the mistakes typically ascribed to McNamara for his role during the Vietnam War, chiefly, his putative naive optimism about the situation in Vietnam and his blind hawkishness. In his diary, McNaughton recorded: “McNamara, the day before we left for Greece, remarked to Tim Hoopes and me that ‘we’ve made mistakes in Vietnam … I’ve made mistakes. But the mistakes I made are not the ones they say I made.’ I said, ‘I know.’ The fact is that he believes we never should have gotten into the combat role out there.”10 The new evidence presented here supports McNamara’s conclusion and suggests that he had often been prescient about problems with the US involvement in the war, including the economic costs of a growing commitment to Vietnam, the inherent weakness of the South Vietnamese ally and eventually, the failure of the Johnson administration to produce a clear and viable strategy.

Drawing for the first time on the full body of primary evidence, this book reinterprets McNamara’s role in a war so closely associated to his name. By extending the research on Vietnam to bring together other bodies of literature, for instance, economic or bureaucratic histories, another interpretation of McNamara is possible. Moreover, new sources, in particular transcripts of the Kennedy and Johnson tapes, McNamara’s handwritten notes during his trips and hearings, his calendar, Yarmolinsky’s papers and McNaughton’s diaries shed a different light on his interaction with colleagues and provide invaluable evidence that the gap between McNamara’s public and private persona was wider than was heretofore known. The written record looks very different when it is juxtaposed against these other sources.11 McNaughton’s diaries, for example, show just how substantial the difference between McNamara’s written statements and his private thoughts were; the presidential recordings shed light on how much, or little, of McNamara’s written recommendations were actually representative of his own views; and the economic papers often explain the timing of key decisions.

By looking at McNamara’s decisions for Vietnam from the bureaucratic vantage point of the OSD, new findings emerge about his “mistakes” and new counterfactual questions add to the more commonly asked, “What would JFK have done?” They include: could the counterinsurgency strategy in Vietnam have worked if it had been scrupulously applied into the Johnson administration? Could a less militant SFRC have permitted a viable MAP-led program in South Vietnam? Could a stronger and more creative State Department have prevented the seemingly inexorable process toward a military solution in South Vietnam? What would have happened if Johnson had been less a New Dealer and more a fiscal conservative as his predecessor had been? Would an alternative view of civil-military relations have produced better outcomes? And, finally, would a less loyal Secretary of Defense, on balance, have been better for the country?

What Would JFK Have Done?

One of the more remarkable outcomes of researching this period has been to become aware of how men who were otherwise rational, controlled, even cold, could also be so personally and emotionally attached to the Presidents they served. This was particularly true with Kennedy. Elspeth Rostow, who undertook many of the oral history interviews for the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, placed a cover letter on her interview transcript with General Taylor, which read:

During the space of four days I watched two men talk for the record about Jack Kennedy but in both cases the record will be incomplete. One was Maxwell Taylor, the other was Joseph Alsop. Neither could explain why the President means so much to him, neither had known the depth of his affection until November 22. Alsop, after finishing the tape, said: “I had no idea that I loved him. I don’t go in for loving men. But nothing in my life has moved me as it did – not even the death of my father. And everyone has said the same. Ros Gilpatric – now Ros doesn’t go in for men, don’t you know – Ros said he’s never got over it. And Bob McNamara said the same thing. And Mac Bundy. As if he were the one thing they most valued and could never replace.” Joe was walked around the room as he talked, the parrots were squawking, and he took off his glasses angrily to wipe his eyes. It was different at Ft. Myers. The General was talking about the 22nd of November in his usual efficient, precise way. The tape was on. Suddenly he stopped, sitting very stiffly in his chair and looking out at the flagpole in front of the house. He was crying too much to continue. There is a pause on the tape, and then we go on.12

Rostow’s notes provide insight into the depth of affection and loyalty these men showed President Kennedy both during his time in office and after his assassination. Personal relationships mattered in the Kennedy administration and shaped the substance of policy. At the same time, the trauma of the assassination no doubt contributed to many of these advisors’ arguments in later years that Kennedy was determined to withdraw from Vietnam on the eve of his death. His loss was not just a personal tragedy but also a national tragedy, whose ripple effects flowed all the way to Vietnam.

This book does not necessarily exclude their arguments; they are perfectly compatible. The book does, however, offer another, less glamorous story. It contends that the story of how the CPSVN was agreed on and eventually dropped, and how the escalation of US involvement in Vietnam occurred, is also a bureaucratic one. In practice, policy on Vietnam was a product of compromise and adaptations to what was organizationally and financially possible in Washington and Saigon. In that bureaucratic story, McNamara was the leading advocate for withdrawal whenever that option was on the table; he was its main architect and driving force.

What If Mcnamara Had Inherited Another Model for Civil-Military Relations?

As he told the Harvard faculty in the wake of his Montreal speech, for McNamara, his job was to keep the lid on Vietnam and manage a department; it was not to cast doubt on existing doctrines. As soon as he began to concern himself with Vietnam in the spring of 1962, McNamara tried to keep a lid on economic costs and on pressures to escalate as he balanced civilian and military priorities and concerns. In this respect, he was following the philosophy of civil-military relations behind the Defense Reorganization Act to the letter. As the act envisaged, his role was not to comment on strategy but to organize “effective, efficient and economical” military resources in the service of civilian objectives and strategy. He organized the services in “unified direction under civilian control of the Secretary of Defense.”13

The process of setting strategy was a one-way street. Civilian advisors were responsible for articulating a strategy, and relevant military advisors translated it into an operational strategy. The Secretary of Defense’s role was to ensure that the two matched, that force structures and budgets were suitably aligned. To begin to comment on strategy would introduce a feedback loop where the parochial priorities of the services could distort strategy. In so doing, it would undermine McNamara’s central achievements at implementing civilian control.

This was not to say that McNamara did not favor one strategy over another. To a large extent, civilian priorities conditioned his enthusiasm for counterinsurgency in the Kennedy years and for the bombing program in the Johnson administration. Both promised the economical and civilian-controlled application of force. Like the barrier concept, they were also designed to avoid expensive troop deployments. The central point of defense economics, as McNamara’s “whiz kids” developed it, was that existing economic conditions determined the breadth of commitments any administration could take on and the resources they could responsibly allocate to those ends.

McNamara understood the economic costs inherent to an expanding commitment in Vietnam. In many ways, the CPSVN and the bombing program were perfect platforms for McNamara to display his achievements at the Defense Department. They showed his ability to bring the Chiefs into line with a new and civilian-led strategy. The CPSVN also addressed Kennedy’s economic priorities while providing an economically promising model for intervening in the wars of national liberation in which the President had taken an interest. Furthermore, it showcased how his new investments at the Defense Department, notably in air- and sealift capabilities, could serve those objectives. Even when the CPSVN process stopped, for reasons that had more to do with Johnson’s economic and political preferences than with the situation on the ground per se, McNamara foresaw the domestic and economic implications of the chosen policy.

In assessing McNamara’s contributions to the problems of Vietnam, a central question emerges: what was the alternative model of civil-military relations given the history of the OSD up to this point? Was it to allow the armed services a greater voice in setting strategy at the outset? As H. R. McMaster has persuasively argued, the Chiefs may not have been capable of doing so. When they made recommendations that diverged from McNamara’s framework, they often failed to factor in the economic consequences of the military actions proposed and the Cold War context, in which the United States’ international image also mattered. Alternatively, was it for the Defense Department to take on a greater role in diplomatic aspects of the conflict, since McNamara was inclined to be “less rigid” about negotiating? The evolution of the OSD and the underlying progression of civil-military relations until the 1960s made both options problematic.

What If the State Department Had Been Stronger?

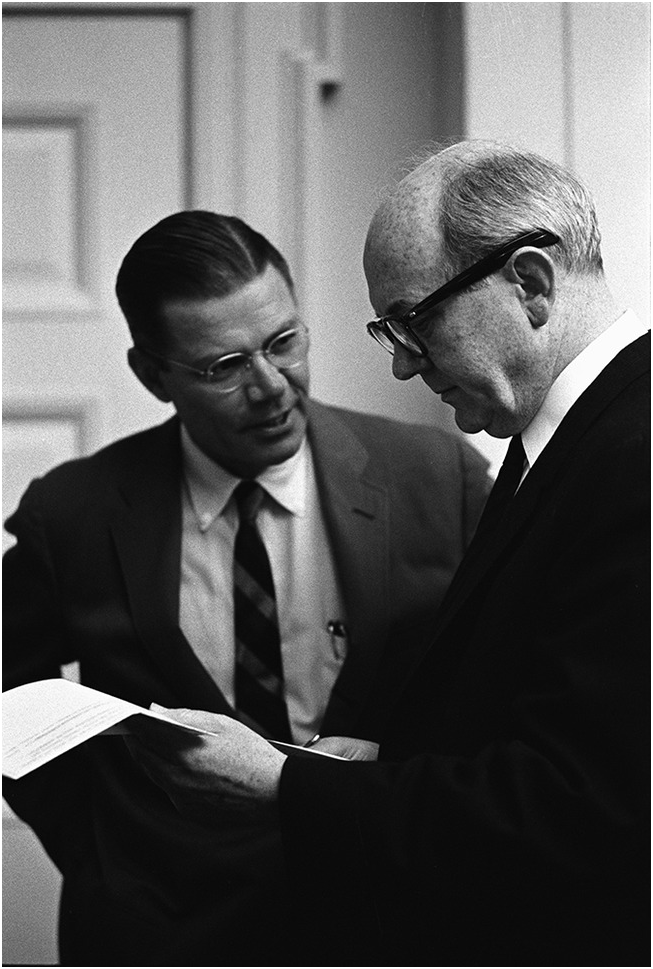

By understanding how McNamara conceived of the OSD in relation to the making of strategy, the responsibility for choosing the right or wrong strategy shifts away from the Defense Department and toward the State Department and White House. Historians have not been kind to Dean Rusk and this book will not soften assessments of his contributions on Vietnam, although it does raise the question of whether escalation in Vietnam might have been different if there had been a stronger, better-run State Department (see Figure C.1).

Figure C.1 Secretary of Defense McNamara (left) in conversation with Secretary of State Dean Rusk, July 25, 1965. Despite their differences on policy matters, McNamara had great affection for his colleague.

Hindsight has not necessarily colored the criticisms that historians have leveled at Rusk; they already existed at the time. Advisors at the State Department and beyond, not least McNamara himself, were regularly frustrated with him then and even more so in later years. Despite his personal affection for Rusk, one commentator correctly assessed Montreal’s speech as an expression of McNamara’s “dissatisfaction with the unimaginative and inflexible policies in the State Department.”14 As early as 1961, Rusk’s Ambassador to Vietnam, Nolting, rather undiplomatically wrote to his boss: “vigor in the Department of Defense in this situation needs to be matched by equal vigor in the non-military aspects if the proper proportions are to be maintained in our total effort there.”15 A year later, CINCPAC observed, “State waffles and evades.”16

Rusk has served as a useful foil to historians who have tried to add nuance to their assessments of other advisors in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. As an “unyielding, unquestioning rock of containment certitude” with a quiet demeanor, he stands in contrast to his colleagues with their private conflicts and public charisma.17 There was some truth also to Rusk’s observation that McNamara would inevitably “end up looking like a dove” because his role was “to present the arguments for limiting military force,” whereas Rusk’s was to defend South Vietnam “in the face of those who would call the whole thing off.”18 As a result, Rusk can easily be caricatured.

Nevertheless, Rusk’s mistakes were real and multiple, and trickled down throughout the Johnson administration when his role became central to articulating a strategy for Vietnam and to opening avenues for a political settlement. In producing post-mortem assessments of the failures in Vietnam, many key advisors pointed the finger at bureaucratic forces and specifically at Rusk’s weakness in representing a civilian view. Hilsman, for instance, explained that the responsibility of the White House and especially the State Department was to “leverage political aspects,” something they did not do.19 Paradoxically, because McNamara was so efficient as a manager, and despite his personal reluctance to define problems as primarily military, he made it easier for the President to do just that. He became a victim of his own success.

In part, as Yarmolinsky noted, State did not “leverage political aspects” as much as it could have because, contrary to Huntington’s concerns in The Soldier and the State, civilians had “allow[ed] themselves to become militarized.”20 President Johnson’s suggestion that McNamara should “lay up the plans to whoop the hell” out of adversaries in South Vietnam speaks to this. Similarly, in later years, McNamara was frustrated at Rusk’s intransigence and his espousal of the “victory ethos” of the military. To McNaughton, he explained that he “agreed with me that our increased deployments each time were hoped (by him and me) to provide strength from which a compromise could be struck; each time Rusk kept the US eye on the VC total capitulation!”21 The failure of negotiations was not Rusk’s alone but he consistently downplayed the value of existing peace overtures. In turn, without political channels, McNamara’s attempt at “communication” through bombing made no sense.

Could the Counterinsurgency Strategy under the Kennedy Administration Have Worked?

Under the Kennedy administration, the hurdles to properly organize for counterinsurgency were also rooted in weaknesses at the State Department. The Kennedy administration made some leeway in terms of organizing for counterinsurgency in new, more civilianized ways, for instance, through the Special Group (CI). However, Hilsman and his colleagues always worried about the ability of the US government and its fragmented agencies to work together coherently in the field. In November 1963, as the CPSVN took hold in Vietnam, Hilsman worried that “once the MACV/CINCPAC/JCS channel was set up, it would inevitably become formal, requiring JCS action and Special Group action for every move, thus getting us into a somewhat rigid position that would make timing to fit the political situation difficult.”22 Although the CPSVN brought order and a degree of secured funding for Hilsman’s preferred program, it also removed the flexibility and informality that his program required operationally.

In the early years of US involvement in Vietnam, decision-makers quarreled and struggled to find the right balance of responsibility across the different government agencies. When the Defense Department took over the CIA and USAID’s programs under Operation Switchback in 1962, field officers complained but were silenced as their bosses weighed up the budgetary advantages. Later, Yarmolinsky, writing to William Kaufmann, a former colleague, explained: “I agree that we have come to understand that the threat of sub-limited war requires more than just a military response but I question whether we are ‘learning to orchestrate all the instruments.’ Aren’t we rather still in the stage of having learned that they need to be orchestrated, but are still having a good deal of difficulty even getting them to harmonize – and too often the violins end up several bars after the drums and cymbals?”23 In each instance, bureaucrats did not want to shake the boat too aggressively and held on to the hope that existing bureaucratic arrangements, even if they were less than ideal, might work.

When the counterinsurgency program was gradually dropped in the transition to the Johnson administration, Kennedy’s erstwhile counterinsurgency advisors in the NSC and State Department complained. They were impotent before a President and Secretary of State uninterested in their ideas and alarmed at the chaotic situation in South Vietnam. While McNamara could ignore or suppress negative reports from the field in the lead-up to the October 1963 NSC meetings, it became much more difficult to do so in the aftermath of the Diem assassination with stepped-up infiltration from the North and chronic political instability in the South. This raises another question, namely could the counterinsurgency strategy have worked with changed circumstances on the ground?

Could Different Funding Arrangements in Washington Have Produced Different Outcomes?

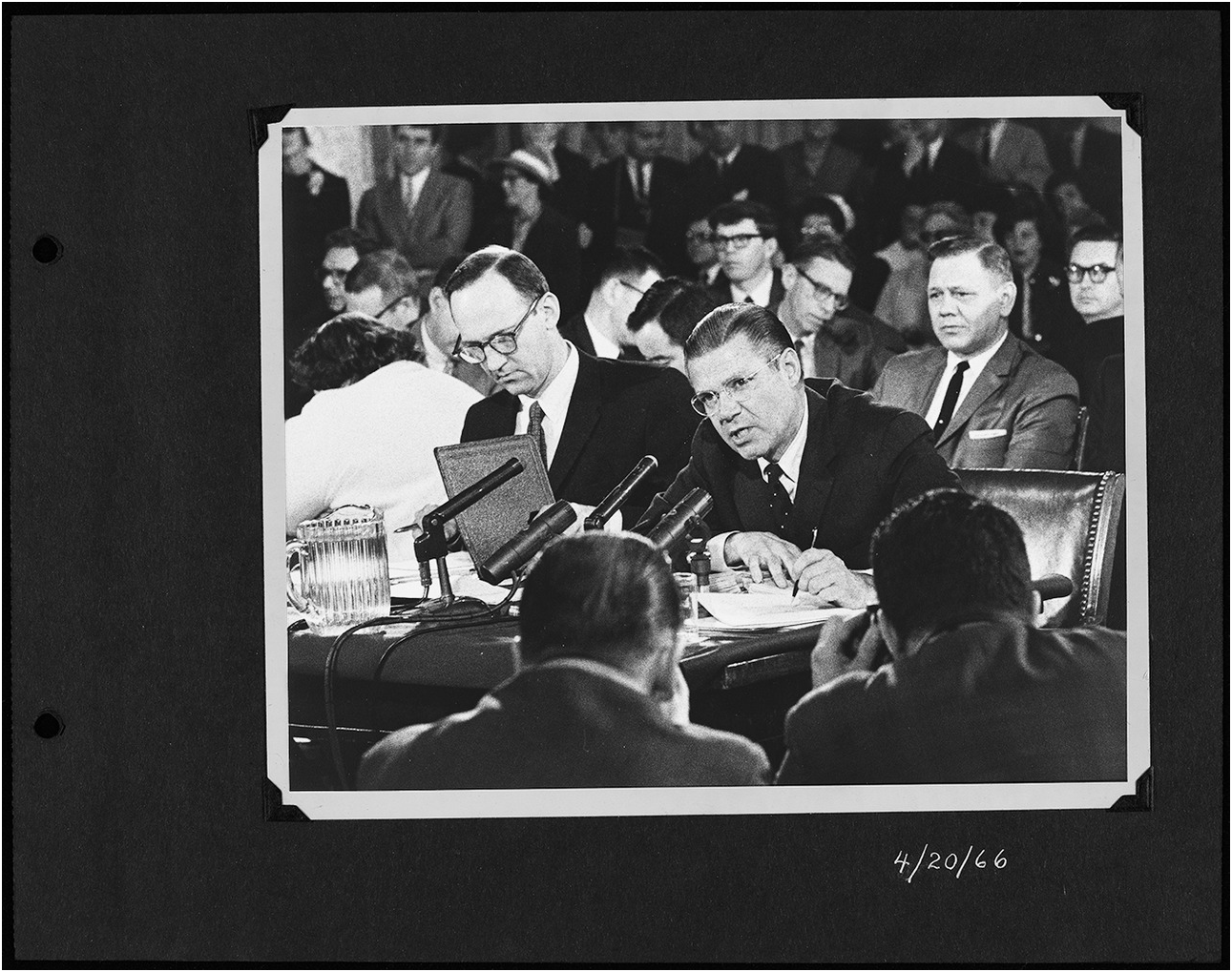

The imbalance in the State-Defense relationship was not just the product of personalities and of each Secretary’s abilities and weaknesses. It was also a funding story that to some extent was beyond the control of both. Military solutions were more readily available and funded. Because military approaches were easier to fund and the Defense Department was better configured to organize complex operations, they produced what Yarmolinsky called “centrifugal tendencies.” Ultimately, as operations in Vietnam became more extensive and, therefore, expensive, the more likely it became that responsibility for them would be shifted to the Defense Department. Moreover, with a MAP and USAID program under continuous attack, the budget naturally shifted to the services. This bureaucratic dimension was at the heart of McNamara’s comments in Montreal (see Figure C.2).

Figure C.2 A page from John T. McNaughton’s scrapbooks: McNaughton (left) and Secretary of Defense McNamara (right) attend SFRC hearings where they defended the value of the Military Assistance Program, April 20, 1966. McNamara would build on this testimony during his Montreal speech the following month.

As Yarmolinsky added, faced with “built-in deadlines” that are inherent to crises, Presidents, he argued, turned to “what they can do best,” which, in the US system, was invariably military solutions. With Johnson particularly, military options promised a degree of short-term success to a politician who wanted “something,” that is, quick-fix solutions that were easily deployable. As an agency that was set up to prepare for contingencies and to deal with “large organizational problems,” the Defense Department, Yarmolinsky argued, “out-perform[ed] State” each time.24 McNamara took over the problems in Vietnam in 1962 because his department could more easily absorb the costs involved and because he and his staff promised to bring order where other agencies, especially the State Department, had failed. As escalation occurred, he could draw on a “strategic reserve” surreptitiously, whereas civilian agencies had no reserve resources to speak of.

Both Hilsman and Yarmolinsky suggested that the underlying problem in the US government and in Vietnam specifically was that resources were consistently siphoned to the Defense Department rather than to State in the first place, because it was “harder to galvanize people” around the State Department, which lacked “the constituency or natural allies in industry or Congress,” both of which the Pentagon had.25 For Yarmolinsky, flexible response had actually made the problem worse. Rather than “demilitarizing the process,” McNamara’s reforms had “only prun[ed] the branches of the military tree. It continued to flourish, stunting the growth of the civilian organisms that grew in its shadow.”26 Flexible response had made the Department of Defense even more ubiquitous because it made it nominally applicable to an even greater range of contingencies. The services first became involved in Vietnam precisely because they were encouraged to use it as a laboratory for their new responsibilities under flexible response.

Yarmolinsky wrote that “So long as the present military means are available, situations like Vietnam are going to recur”: without a more wholesale reform of the policy process, military solutions would always be favored. Only “political leadership that exercises superhuman qualities” could prevent it.27 Paradoxically, by investing and producing a well-run Defense Department, the United States had reduced its flexibility in its interactions with the world.

Moreover, it is a bitter irony that the same senators who expressed concern about the growing commitment in Vietnam as early as 1962 and worried that it was becoming overmilitarized hastened the process along. The advocate senators in the SFRC, including Fulbright and Mansfield, inadvertently reduced their leverage over the administration’s Vietnam policy by attacking the MAP program. Even while Russell and his colleagues on the SASC might have expressed reservations over the commitment in Vietnam as well, they were more concerned with ensuring that the services had all the resources they asked for. In so doing, they shifted the balance toward military options.

What If Johnson Had Been Less of a New Dealer?

This book raises another counterfactual. Given the different economic sensibilities of Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, would the war in Vietnam have happened if Johnson was less of New Dealer? Gaddis and others have presented Kennedy as a spendthrift Keynesian. This book suggests otherwise. Instead, by looking at the early decisions on Vietnam from the vantage point of the OSD, an altogether different interpretation emerges. As Secretary of Defense, McNamara was uniquely positioned to see how economic constraints weighed on strategic choices. Contrary to Gaddis’ contention, Kennedy was troubled by what he perceived as the United States’ economic weaknesses. His and McNamara’s decisions in Vietnam into 1963 were a product of a feeling not of omnipotence but rather of vulnerability. In this, he was very different from his successor, who disapproved of Kennedy’s fiscal conservatism.

McNamara and Dillon’s efforts, most notably on the balance of payments during the Kennedy administration, challenge the idea that the administration saw itself as being at the apex of US power and militancy. It disputes the argument that under Kennedy “optimistic America answered the summons of the trumpet and went to war in Vietnam”28 and a related point: that McNamara advocated or even favored military solutions for Vietnam. The Kennedy administration chose a limited strategy that was contingent on self-help for Vietnam in part because of what Kennedy perceived as “limitations on the ability of the United States” to “bring about a favorable result” there.29

By the spring of 1962, international crises in Laos, Berlin and Cuba had humbled the Kennedy administration. However, in many respects, its more modest approach to South Vietnam predated these crises and reaffirmed the central idea of Kennedy’s inaugural address, which was less a “clarion call” for US militancy and more a call for people in the United States and abroad to become agents in their own future or, in the words of the address, “to help them help themselves.”30

Refocusing US foreign policy on the notion of self-help gained added urgency in 1962 when a jump in the balance of payments deficit and the gold outflow occurred. Just as Eisenhower had before him, Kennedy worried that an unstable economic base and international monetary system could undermine every aspect of the US power.31 Together with Dillon, McNamara led efforts to redress the deficit. McNamara played a leading part on the balance of payments because the Defense Department’s overseas operations largely drove the deficit and because his cost-saving reputation, the quality that distinguished him above all else, was at stake. As a result, the CPSVN timetable directly matched the timing and pace of McNamara’s efforts to address the balance of payments outflow.

With Kennedy’s assassination, many things changed. This included a change in advisors on Vietnam, to the clear detriment of key players on counterinsurgency, including Hilsman and Robert Kennedy. Johnson’s preference for military solutions also changed the general tenor on Vietnam, as did his search for consensus among his advisors. One of the most decisive changes, however, derived from his different appreciation of economic problems. With less restraint on the economic front and more fiscally conservative advisors such as Dillon sidelined, the pressures to reduce commitments in Vietnam and elsewhere diminished at a key juncture in the escalation of the US involvement.

From 1965 onward, McNamara and others raised economic concerns with Johnson and worried that escalation in Vietnam, if it was not matched with either a tax increase or tighter domestic spending, might produce inflationary pressures. The President’s commitment to the Great Society and to surpassing Roosevelt’s achievements under the New Deal trumped their judgments. He tried to bully and censor officials, such as Federal Reserve Chairman Martin, who confronted him with the economic implications of his decisions for Vietnam. He feared a congressional debate over his decision for Vietnam because, above all, he wanted to protect his Great Society programs. If Johnson had been a little more fiscally conservative, he might have been more willing to critically question the value of the US commitment in South Vietnam.

What If McNamara Had Defined “Loyalty” Differently?

This brings us to McNamara himself, the man behind the office. Speaking of his boss and friend, Yarmolinsky commented, “My own view … is that if McNamara is remembered at all by history, he will not be remembered as a manager, he will not be remembered as the ‘architect of Vietnam’ although he may be remembered unhappily that way … But I think he’ll be remembered as the person who was, really, the first and most effective educator of the American people on the true nature of military weapons.”32 Ensuring that legacy or “building his image” as he said to the Harvard faculty might have been an objective of his speech in Montreal and other efforts in the spring of 1966, but it could not ultimately remove the overbearing shadow of Vietnam.

In Stewart Alsop’s article, McNamara had said, “My mistakes have been mistakes of omission, not commission.”33 Responding to the article, McNaughton “told him that one of his greatest ‘errors of omission’ (about which he had told Stewart Alsop) was in continuing to recommend force deployments in order to give us bargaining leverage when the government was not taking any bargaining steps” (emphasis in original).34 A less charitable way of paraphrasing McNaughton’s comment is that McNamara recommended troop deployments without any faith in their ability to achieve anything at all. By 1968, some 20,000 US servicemen had died in Vietnam and many more South and North Vietnamese, and 1968 would become the deadliest year yet.35 McNamara’s role in that was no small omission.

McNamara’s loyalty to the President, which served his bureaucratic ends well, became troublesome when he became the public face of a program that he understood was fundamentally flawed. Because of his loyalty to the President, he “omitted” to express his doubts and legitimate questions even while he oversaw ever-increasing troop deployments and casualties. Crucially, it led him to “omit” information to the Congress, whose important constitutional responsibility it was to oversee the multifaceted implications of the growing commitment in Vietnam. When the administration decided to deploy Marines to Da Nang, Johnson initially suggested that McNamara might announce that they were a “security group” or something equally innocuous. McNamara resisted, by saying that the administration would be “accused of falsifying the story.”36 His comment suggests that he understood that the ambiguity that Johnson cultivated was tantamount to a lie, yet he continued to play a central role in obscuring the reality of the administration’s decisions for Vietnam.

This raises an additional counterfactual, namely could the war in Vietnam have gone differently if McNamara had not been so loyal and instead voiced and acted on his concerns? Although McNamara considered leaving the Johnson administration as early as the fall of 1965, he nevertheless stayed on until February 1968. When he did break ranks with the administration, he replaced his loyalty to Johnson with renewed loyalty to the Kennedys. His disenchantment with the war was, in fact, intimately connected to Robert Kennedy’s ascendancy as a political threat to Johnson.

The idea that McNamara was uninformed or did not seek advice beyond traditional military channels was not borne out in the research leading to this book. Quite the contrary. In addition to his long exchanges with John Kenneth Galbraith and Robert Thompson, which began in 1962, in the fall of 1963, he spoke to Patrick Honey, who convinced McNamara to oppose the coup against Diem, not because of any moral concerns but because the alternative leaders could not sustain the program he had laid out for South Vietnam. In this assessment, Honey and McNamara were spot-on. In later years, McNamara drew on Bernard Fall, who was critical of the bombing program and its “confidence in total material superiority,” and warned the Johnson administration that it was tying its credibility to a doomed and “fundamentally weak” South Vietnamese partner.37

Although McNamara knowingly accepted the label that Vietnam was “McNamara’s war,” behind the scenes the situation at the OSD was more complex. Some of the most virulent complaints emerged at ISA even if they rarely went beyond its walls.38 In some respects, ISA was the logical place for dissent as it bridged the capabilities of the Defense Department and the strategy, or lack thereof, of civilians at the State Department. Ultimately, it was at ISA under McNamara that the policy of Vietnamization emerged, a policy that eventually provided the basis for US disengagement from Vietnam. Paul Warnke at ISA, who played a leading part in designing Vietnamization, stayed on to serve both of McNamara’s successors, Clark Clifford and President Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Defense, Melvin Laird.

Ultimately, McNamara emerges from this history as a man who was concurrently both a hawk and a dove and who was also more reflective than conventional interpretations allow. While the OSD’s “checks and balances” characteristics, especially insofar as they led to McNamara’s support for withdrawal in the early years and for pacification efforts throughout the war, could qualify McNamara as a “dove” on Vietnam, his unrepentant defense of the use of technology throughout the war was “hawkish.” From the outset, McNamara encouraged defoliation programs and applied similar statistical models to the bombing campaign in Vietnam to those he had used during World War II. If by April 1966, he had decidedly turned against the war, he nevertheless defended the idea of building a barrier between North and South Vietnam. Put together, his policies on Vietnam do not fit into a hawk/dove dichotomy.

McNaughton’s diaries and the telephone recordings in particular do not support the notion that McNamara believed the idea that Fall criticized, namely that military tools could achieve what were ultimately political objectives in South Vietnam. In a recently declassified oral history, McNamara made a remarkable admission for someone who, on the written record, planned for increased levels of military force: “I don’t think I ever believed that a military victory, in the normal sense of the words, was achievable.”39 The preceding chapters tend to confirm his observation.

However, McNamara continued to muffle his and his colleague’s dissent in order to fulfill his professional obligations to the President as he narrowly defined them. McNaughton observed, “So much in government depends upon subordinates taking hints and carrying out the mood of the President … Bob (and I) is much less effective if the President is really trusting the Chiefs, for example. Such a shift in outlook makes quite a difference in the ‘power’ one (ISA) has – whether he is listened to, gets his way, etc. We’ll see how things go.”40 Both Kennedy and Johnson commanded loyalty; Johnson also demanded it. When he sensed McNamara’s growing discomfort with policies, he blamed him for leaks and for “disloyalty in the highest ranks [with] various Cabinet members spreading anti-administration information around town.”41 As McNaughton correctly observed, as soon as McNamara stopped presenting the views he knew the President wanted to hear, he would be removed.

Understanding McNamara’s strict codes of loyalty is fundamentally important to grasp how someone who tried to keep the United States out of Vietnam could also be held responsible for the war. In many respects, he was the perfect fall guy, someone who held his reservations and concerns quiet notwithstanding his comments in Montreal. McNamara commanded the same loyalty from his colleagues as he showed to the Presidents he served. Some went on to dedicate books to him. Their treatment of Ellsberg when he betrayed their loyalty codes and leaked the Pentagon Papers – crossing the street to avoid him, treating him as an outcast – derived from their sense that he had breached their codes of loyalty.

However, every quality, in excess, can become a tragic flaw. In November 1966, McNamara was invited to a dinner at Robert Kennedy’s home for the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, whom he had cited before his October 1963 trip to Vietnam. After a frank exchange where the poet accused the Secretary of being a “crocodile of war” and McNamara shared his own frustrations with his inability to end the war promptly,42 the poet left, saying, “They say you are a beast. But I think you are a man.”43 McNamara’s most important mistakes on Vietnam were situated in his human flaws. His sense that it was “heretic” to speak out when he understood the futility of continued troop deployments, or when he understood the potentially catastrophic impact of Vietnam on the domestic and international economic situation, is a terrible mark on his legacy.