The question of whether Supreme Court justices recuse themselves from cases when they should have received considerable attention in recent years. Reference RobertsChief Justice John Roberts (2011) devoted his 2011 Year-End Report on the Federal Judiciary to the subject. Much of the controversy has centered on accusations that the justices are not abiding by statutory and ethical guidelines when deciding whether to recuse themselves from cases, instead choosing to participate in high-profile cases despite apparent conflicts of interest. For example, Justice Elena Kagan participated in the landmark health-care decision National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012) despite having been Solicitor General when the legal defenses for the Affordable Care Act, or “Obamacare,” were first developed (Reference BarnesBarnes 2011; Reference BiskupicBiskupic 2011). Likewise, Justice Clarence Thomas was criticized for declining to withdraw from the same case despite the political activities of his spouse, who publicly opposed Obamacare (Reference ThomasThomas 2010).

Missing from the discussion is a rigorous analysis of when recusals on the U.S. Supreme Court are more likely to occur. In fact, recusals are among the poorest understood features of judging on the Supreme Court, despite the large amount of legal commentary on the subject (Reference BamBam 2011; Reference BassettBassett 2005; Reference FlammFlamm 2010; Reference FrostFrost 2005; Reference HenkeHenke 2013; Reference RobertsRoberts 2004; Reference SampleSample 2013; Reference StempelStempel 1987). Political scientists have explored the consequences of recusals (Reference Black and EpsteinBlack and Epstein 2005), finding that recusals do not typically cause the justices to divide evenly, but they have yet to examine the antecedent question of why the justices are recusing themselves in the first place. Exacerbating the problem is the fact that the justices have consistently refused to explain their behavior. When they withdraw from disputes, the most that one can typically expect is a note in the U.S. Reports stating that a justice “took no part in the consideration or decision of this case.” The justices rarely say more, declining even to make public the names of cases in which they considered recusing themselves but did not. One commentator described the justices' reluctance to speak on the matter as a “conspiracy of silence” (Reference WeaverWeaver 1975: 22).

Yet, understanding the recusal process is vitally important. At the most basic level, the participation of justices has the potential to affect who wins and who loses cases. Given the ideological consistency of the justices' voting records (Reference Segal and SpaethSegal and Spaeth 2002), and how closely divided they have become on important issues (Reference ClarkClark 2009; Reference KuhnKuhn 2012), it is reasonable to expect case dispositions to turn on the disqualification of particular justices. In the context of the health-care dispute, for example, Justice Kagan's recusal would have denied the majority the fifth vote that it needed to uphold the constitutionality of the individual mandate. Assuming that no other justices changed their votes, the Court would have been deadlocked, with no majority opinion to guide the lower courts, and leaving the future of the Affordable Care Act uncertain.

More generally, understanding the recusal process is important because it helps us to understand the extent to which the justices, and by extension the federal judicial system, are committed to principles of impartial justice. The promise of an impartial judiciary is a bedrock principle of the American legal system and one of the primary justifications for granting life tenure to federal judges. It is also the animating principle of the federal recusal statute, which requires federal judges to disqualify themselves when their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”Footnote 1 The statute specifies categories of behavior in which disqualification is warranted, such as when judges have financial stakes in cases, when they have participated previously in the same proceedings as counsel, and when they have expressed opinions on the merits of the particular cases in controversy, among other considerations.Footnote 2 Yet, the lack of transparency in the recusal process has made it difficult for Americans to evaluate whether the justices are realizing the statute's ideals, or for society to hold accountable those justices who are not.

According to Chief Justice Roberts, the justices follow the statutory guidelines and they take their ethical responsibilities seriously. “We are all deeply committed to the common interest in preserving the Court's vital role as an impartial tribunal governed by the rule of law,” he wrote in his 2011 Year-End Report. “I have complete confidence in the capability of my colleagues to determine when recusal is warranted. I know that they each give careful consideration to any recusal questions that arise in the course of their judicial duties” (10). These comments echo testimony that Justice Anthony Kennedy gave before a congressional subcommittee in 2011. “Of course the Court has to follow rules of judicial ethics,” he said. “That is part of our oath. That is part of our obligation of neutrality” (Transcript 2011).

In tension with these assurances is research finding that Supreme Court justices are policy-motivated decision makers (Reference Segal and SpaethSegal and Spaeth 2002) who are forward thinking about the consequences of their behavior for the Court's policy output (Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight 1998; Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and J. WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck 2000). We know that policy goals influence the decision on the merits (Reference Segal and SpaethSegal and Spaeth 2002), the assignment of the majority opinion (Reference RosenRosen 2007; Reference WahlbeckWahlbeck 2006), the content of the majority opinion (Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and J. WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck 2000), the decision to grant certiorari (Reference Caldeira, Wright and ZornCaldeira, Wright, and Zorn 1999; Reference PerryPerry 1991), and the justices' conduct at oral arguments (Reference Black, Johnson and WedekingBlack, Johnson, and Wedeking 2012), so there is every reason to think that policy considerations also affect justices' decisions about whether to recuse themselves. Sitting out of cases denies justices the opportunity to influence the final votes on the merits and the contents of majority opinions, policy costs that might sometimes be too great for justices, even if they risk damaging the Court's legitimacy by participating.

Justices also have institutional incentives to participate in cases that they must balance against the statutory and ethical guidelines. Among these incentives is the need for the justices to decide the cases before them, an institutional responsibility that is compromised when recusals cause the Court to lack a quorum or divide evenly. Justices have stated that this “duty to sit” is important to them and can be at odds with the statutory goal of reducing bias. For example, Reference GinsburgJustice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (2004: 1039) has remarked that “on the Supreme Court, if one of us is out, that leaves eight, and the attendant risk that we will be unable to decide the case, that it will divide evenly.” Reference RobertsChief Justice Roberts (2011: 9) repeated these concerns in his 2011 Year-End Report, noting that, unlike lower court judges, who “can freely substitute for one another,” when a Supreme Court justice withdraws, “the Court must sit without its full membership.” If the justices are unable to achieve consensus because their membership is down, important questions of federal law go unanswered, and the justices risk falling short of their responsibilities to resolve disputes and provide checks on coordinate branches. When faced with these possibilities, the justices might determine that the benefits of recusals are not worth the costs.

In this paper I systematically investigate the question of when justices on the Supreme Court are more likely to recuse themselves, covering the years 1946–2010. My expectation is that while Chief Justice Roberts is generally correct, and the justices do abide by ethical guidelines for recusal, the justices will nonetheless participate in cases when the policy consequences of recusals are too great or the institutional need to decide cases and controversies is more important than the goal of reducing bias or its appearance. Many times, the justices might determine that recusals are not worthwhile, even when they are technically warranted.

Consider, for example, Justice Kagan's situation in the health-care case. She certainly could have recused herself. It arguably would been appropriate, given that she was the Solicitor General when the strategy for defending the Affordable Care Act was being developed and she would have argued the case before the justices had she not been appointed to the Court.Footnote 3 Even if there was no actual conflict of interest, the mere appearance of a conflict might have persuaded Kagan to err on the side of caution and to sit the case out, thereby ensuring that the Court's legitimacy would not be threatened by her participation. After all, the federal recusal statute requires justices to withdraw from any cases in which “their impartiality might reasonably questioned,” and there were undoubtedly questions in the popular media at the time about whether Kagan's participation in the case was appropriate (Reference SegallSegall 2011; Reference SmithSmith 2011). But what would a recusal have cost her? The Court would have lacked the fifth vote needed to secure the constitutionality of the act, and Kagan would have missed the opportunity to shape the law in this important area. Surely these opportunities were too great for her, or any justice, to pass up.

Recusals and Judicial Strategy

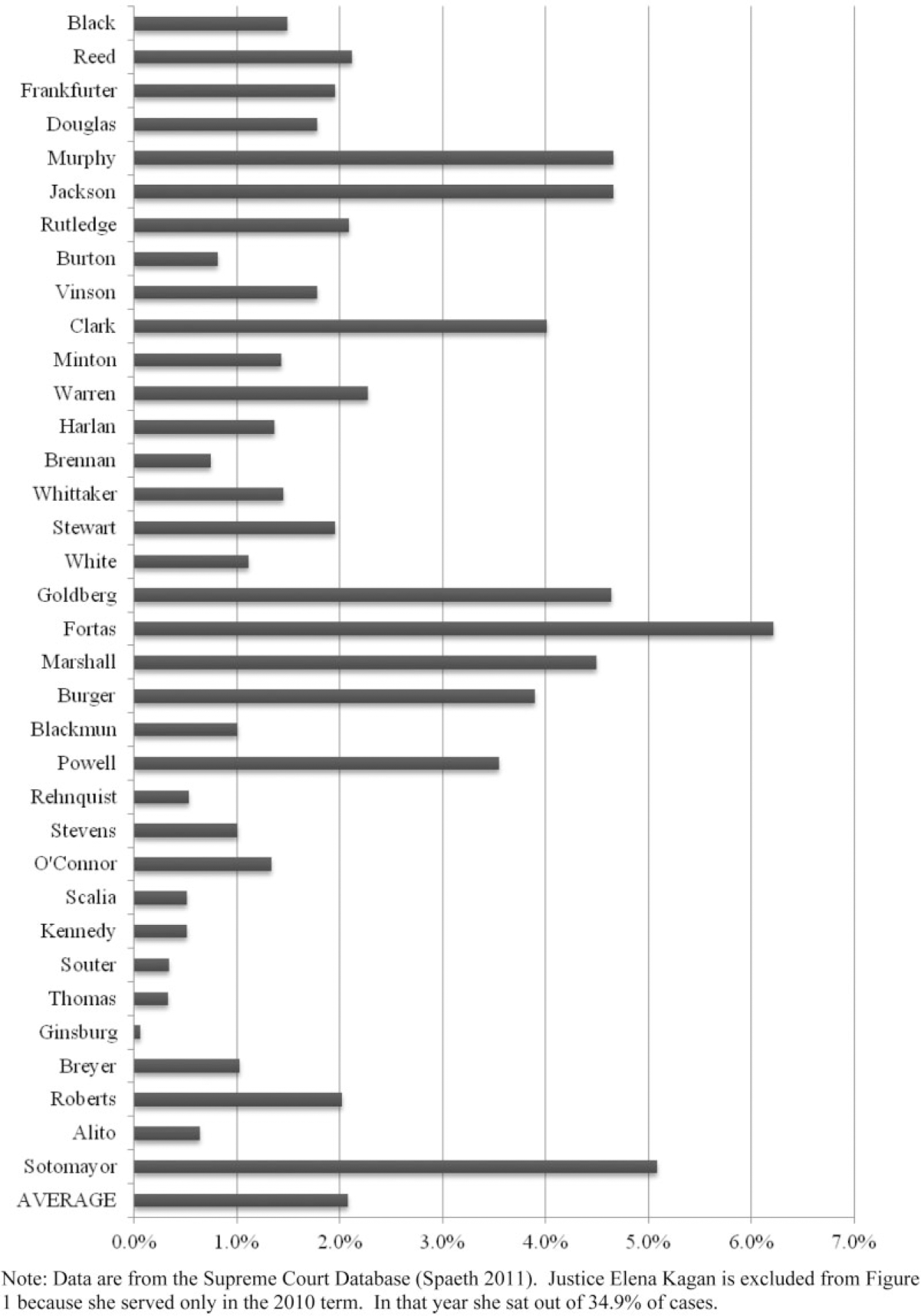

Recusals occur when Supreme Court justices or other judges disqualify themselves from cases, meaning that they play no role in the consideration of the dispute, the voting, or the drafting of the opinions. The purpose of recusals is to enhance public confidence in the judiciary by promoting judicial impartiality, or at least the appearance of it. While Supreme Court justices do not frequently withdraw from cases, recusals are not uncommon. Figure 1 reports the percentage of cases in which Supreme Court justices disqualified themselves voluntarily during their time on the Court between 1946 and 2010, based on data from the Supreme Court Database (Reference SpaethSpaeth 2011).Footnote 4 There is some variation in the rate at which justices withdrew from cases. Justice Fortas had the highest rate, withdrawing from 6.2 percent of cases, while Justice Ginsburg had the lowest rate, at 0.06 percent. Overall, the justices recused themselves from about 2.1 percent of cases.

Figure 1. Percentage of Cases in which Justices Recused Themselves, 1946–2010.

The decision whether to disqualify oneself from a case is technically not voluntary. By its terms, the federal recusal statute applies to Supreme Court justices, reading that, “Any justice, judge, or magistrate judge of the United States shall disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”Footnote 5 While the justices have never conceded that Congress has the authority to regulate their recusal behavior, the justices have repeatedly applied the statute to their conduct.Footnote 6 Yet, regardless of its applicability, the statute lacks meaningful enforcement mechanisms to ensure the justices' compliance. Neither Section 455 nor the Judicial Conference's Code of Conduct for United States Judges requires Supreme Court justices to report the reasons for their recusal decisions, nor is there a higher court to review their practices.Footnote 7 In fact, the federal recusal statute establishes no procedures for Supreme Court recusals whatsoever. For the most part, the justices recuse themselves sua sponte. Recusal motions are rarely filed, perhaps because litigants do not wish to accuse the justices of having biases (Reference BashmanBashman 2005). The justices respond to these motions at their discretion. Therefore, while Supreme Court justices are technically obligated to follow federal guidelines regarding recusals, there is considerable uncertainty about how much they do. One commentator characterized the process as “a personal, independent, unreviewable decision by an individual Justice whether to participate in an individual case” (Reference VirelliVirelli 2012: 1547).

The paradigm that I use to understand recusal practices is the strategic model of judicial behavior, which maintains that judges are policy oriented but constrained by institutional conditions that prevent them from acting sincerely (Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight 1998; Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and J. WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck 2000; Reference MurphyMurphy 1964). The central insight of the strategic model is that because judges are embedded within institutions that have their own norms and practices—and that require collaborating with others—judges must often make compromises when pursuing their policy goals. For example, Supreme Court justices must compromise to win the support of their colleagues on the bench, which is necessary to form majority coalitions (Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and J. WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck 2000). Justices might also seek to appease colleagues off of the bench, such as members of Congress, who have the capacity to curb judicial power (Reference Segal, Westerland and LindquistSegal, Westerland, and Lindquist 2011). Alternatively, justices might feel obligated to conform to professional norms, such as the norm of stare decisis (Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight 1998; Reference Knight and EpsteinKnight and Epstein 1996) or recusal norms, to maintain their legitimacy.

In the recusal context, Supreme Court justices must balance statutory and ethical guidelines concerning recusals against their other policy and institutional goals. Neither recusing nor declining to recuse is costless. Justices who decline to recuse themselves, despite committing ethical violations, risk damaging the Court's legitimacy by undermining public confidence in the integrity of the proceedings. Research has established a connection between the Supreme Court's legitimacy and the public's perception that the justices are principled decision makers (Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson and Caldeira 2009, Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011). This perception might be undermined if improper recusal behavior makes the justices appear biased, particularly if the justices routinely disregard ethical guidelines.Footnote 8 Justices therefore cannot decide never to recuse themselves because they might jeopardize the Court's reputation. To the extent that the Court's power depends on public confidence in the institution (Reference Canon and JohnsonCanon and Johnson 1999), justices have incentives to withdraw from cases when necessary to protect the Court's legitimacy.Footnote 9 The fact that Chief Justice Roberts devoted his 2011 Year-End Report to the subject of recusals is instructive, suggesting that the Court's recusal practices were damaging the Court's reputation.

On the other hand, if justices disqualified themselves from cases whenever they plausibly could, they would compromise their other policy and institutional goals. As described above, it is well documented that Supreme Court justices have substantive interests in policy and that they behave in ways that advance their sincere policy preferences (e.g., Reference Segal and SpaethSegal and Spaeth 2002). If the justices care about the development of the law, and if they would like to see the law reflects their sincere policy preferences as much as possible, then they will seek to avoid routinely recusing themselves from cases. Otherwise, they risk ceding to others the resolution of important federal questions about which they have substantive policy interests.

From an institutional standpoint, recusals can also be problematic because they make it more difficult for the justices to fulfill their responsibility to decide cases and controversies. The “duty to sit” was recognized on the Supreme Court in Laird v. Tatum (1972) by then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist, who suggested that the justices had institutional obligations that they had to weigh against arguments in favor of recusal.Footnote 10 Rehnquist explained that, unlike on the lower federal courts, where judges can be interchanged, there is no one to substitute for absent justices. If too many justices recuse themselves the Court will lack a quorum, which has happened several times in the Court's history.Footnote 11 The absence of a single justice can also be problematic if it causes the Court to divide evenly because then the lower court's opinion is affirmed automatically and the Supreme Court's judgment has no precedential value. In either circumstance, the justices fail to perform their basic institutional functions of deciding cases and controversies and providing guidance to lower courts and litigants on important questions of law.

Since Laird, the justices have repeatedly affirmed that these institutional concerns are important to them, even after the 1974 revisions to the federal recusal statute replaced the duty to sit with a requirement that judges disqualify themselves when their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”Footnote 12 Versions of Laird's rationale appear in the justices' 1993 Statement of Recusal Policy and Roberts' 2011 Year-End Report on the Federal Judiciary. Chief Justice Rehnquist relied on it in a statement declining to recuse himself from Microsoft v. United States (2000), and Reference GinsburgJustice Ginsburg (2004) endorsed the principle in off-the-bench comments. In testimony before Congress, Justice Stephen Breyer was explicit on this point, stating that when making a recusal decision, “you have to remember you have a duty to sit” (Transcript 2011).

While research has not investigated the extent to which the “duty to sit” influences the justices' recusal practices, empirical work has found that the justices pursue similar institutional goals in other contexts. For example, in the agenda-setting literature, it has been established that the justices take seriously their institutional responsibility to review controversies that have divided the lower courts and that present important federal questions (Reference Black and OwensBlack and Owens 2009; Reference PerryPerry 1991; Reference Tanenhaus, Schick, Rosen and SchubertTanenhaus, Schick, and Rosen 1963). The purpose of granting certiorari in these circumstances is not so much to advance policy goals as to promote clarity in federal law (see also Reference Lindquist and KleinLindquist and Klein 2006). It is defensible, then, to take the justices at their word when they say that they feel a sense of responsibility to decide the cases and controversies before them. The justices might choose to prioritize these institutional concerns over the statutory recusal guidelines when they think it is necessary to promote clarity in the law or to fulfill some other obligation.

Indeed, research by Reference Black and EpsteinBlack and Epstein (2005) provides support for this hypothesis. They find that recusals do not frequently cause the justices to divide evenly, occurring less than 6 percent of the time when they were possible, which is below what one might expect if vote divisions occurred randomly. Reference Black and EpsteinBlack and Epstein (2005: 95) do not provide data to explain these findings but suggest that the justices might be selective about when they are recusing themselves: “It simply could be that justices are more likely to recuse themselves in cases they think will not result in a split vote.” This explanation would be consistent with my theoretical expectation that justices follow statutory recusal guidelines less strictly when institutional needs arise.Footnote 13

How, then, might justices resolve these competing incentives? As a general matter, one might expect the justices to follow statutory and ethical guidelines and to recuse themselves from cases when conflicts of interest arise. Abiding by these guidelines protects the Court's reputation by creating a general perception that the integrity of judicial proceedings is being maintained. However, the justices will avoid recusing themselves when their participation is necessary to advance their policy and institutional goals. Because federal law does not require the justices to explain their recusal decisions, the justices can probably evade professional recusal norms from time to time without damaging the Court's reputation, so long as they do not make it a regular practice. Indeed, the justices' silence about their recusal practices—and their unwillingness to generate a written record of their deliberations—might be intended to give them this flexibility. In the next three sections, I develop hypotheses based on the competing statutory, policy, and institutional explanations for recusal behavior. My expectation is that strategic justices will attempt to balance these motivations, abiding by the statutory guidelines except when their other policy and institutional goals are threatened by disqualification. I then test these hypotheses using data from the Supreme Court Database (Reference SpaethSpaeth 2011).

Statutory Considerations

Justices who abide by professional norms for recusals would be expected to follow the ethical guidelines set out in 28 U.S.C. § 455. As revised in 1974, § 455 has two major provisions: section 455 (a), which requires judges to recuse themselves when their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned”; and section 455 (b), which outlines discrete categories of conduct that require recusal. Of these provisions, the one that tends to generate the most recusals is the requirement that the justices disqualify themselves when they have financial conflicts of interest. Section 455 (b) (4) states that a justice shall withdraw from a case when “he, individually or as a fiduciary, or his spouse or minor child residing in his household, has a financial interest in the subject matter in controversy or in a party to the proceeding.” Even if a justice's financial stake in a case is minimal, the justice is still expected to withdraw to avoid the appearance of a conflict of interest. For example, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor frequently recused herself from cases because of her ownership of AT&T stock.Footnote 14 Chief Justice Roberts divested himself of Pfizer stock in 2010 so that he could participate in two cases concerning that company, after previously recusing himself from cases involving Pfizer (Reference LiptakLiptak 2010; Reference ShermanSherman 2010). In another case, the justices lacked a quorum after four justices recused themselves because of their investment holdings or other financial conflicts.Footnote 15 One might therefore hypothesize that recusals will be more common when cases present financial conflicts of interest.

There are at least two ways of investigating the impact of financial conflicts of interest on the justices' recusal behavior. One approach is to focus on the litigants, determining whether recusals occur more frequently when business interests come before the Court. This approach is advantageous because data are readily available and the measure captures most all of the particular financial interests that might lead the justices to withdraw from cases. If there is a correlation between recusals and the presence of a business, corporation, or financial institution as the petitioner or respondent, it is hard to think of an explanation for this finding except that financial conflicts of interest are prompting the justices to recuse themselves:

H1: Justices are more likely to recuse themselves from cases when a business, corporation, or financial institution is listed as the petitioner or the respondent.

Another approach is to focus on the “net worth,” investments, and other financial commitments of particular justices. The problem with this approach is that data are available only after 1980, when the justices were required to disclose their net worth and financial investments by the Ethics in Government Act of 1978. Moreover, focusing on particular investments is likely to be underinclusive because financial disclosure forms understate the extent of the justices' financial conflicts. For example, Justice Alito was criticized for declining to recuse himself in a case concerning ABC Inc. despite owning stock in ABC's parent, Walt Disney Co.Footnote 16 Alito's financial disclosure form listed only the Disney stock. The financial disclosure forms are more consistent in reporting the “net worth” of the justices. When these figures are adjusted for inflation, one can assess whether wealthier justices have different recusal practices from their colleagues:

H2: Justices are more likely to recuse themselves from cases when their “net worth” is high.

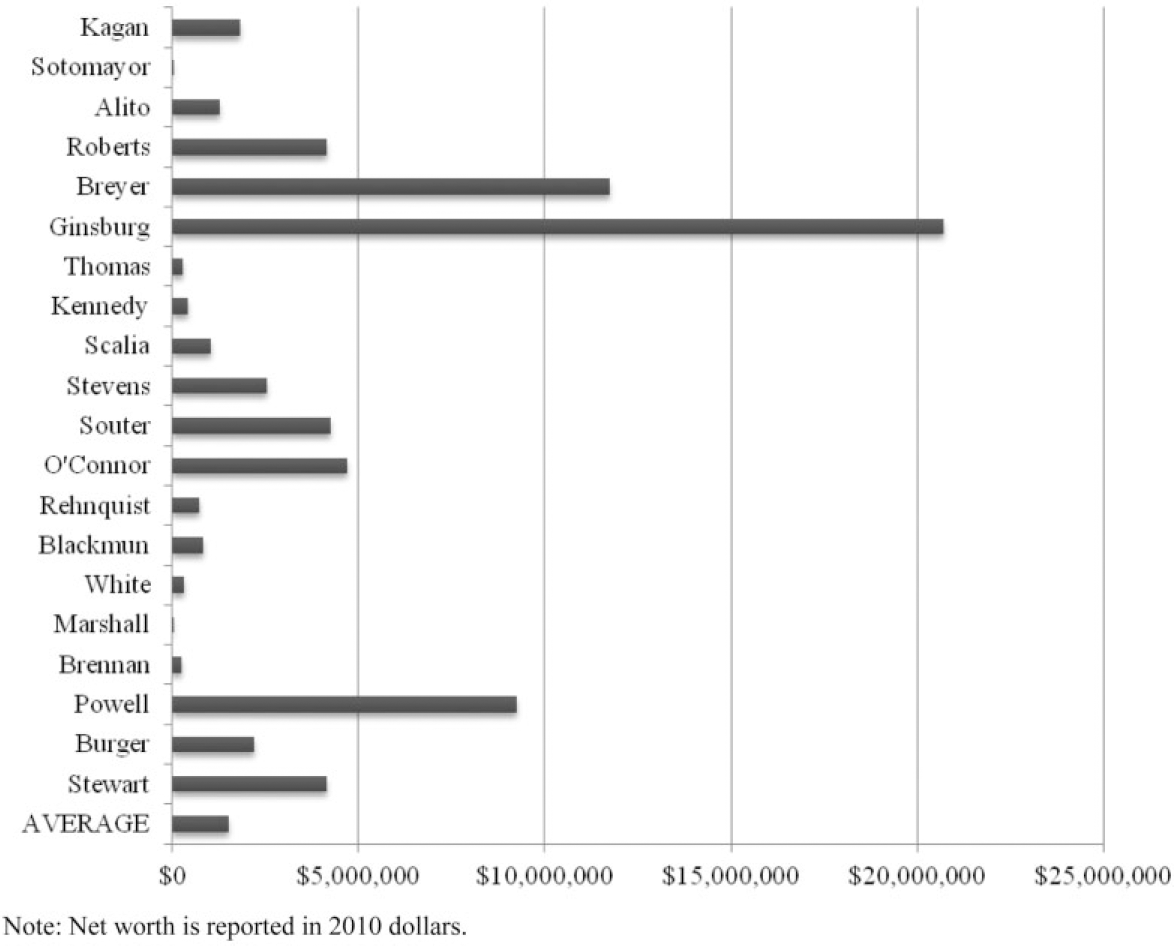

Figure 2 reports the median “net worth” of Supreme Court justices during their years of service on the Court between 1980 and 2010, reported in 2010 dollars.Footnote 17 The wealthiest justice, Justice Ginsburg, had a “net worth” of about $20 million, while the “net worth” of Justice Thurgood Marshall was frequently quoted as $0, with a median of about $36,500 for the period. The median “net worth” for all justices was $1.5 million. I expect that justices with a higher “net worth” will be more likely to withdraw from cases because they are more likely to have broad portfolios of investments that might present conflicts of interest.

Figure 2. Median Net Worth of Supreme Court Justices, 1980–2010.

Federal law also requires the justices to disqualify themselves from cases in which they have “served as lawyer in the matter in controversy,” “served in governmental employment and in such capacity served as counsel, adviser or material witness concerning the proceeding,” or “expressed an opinion concerning the merits of the particular case in controversy.”Footnote 18 For example, Justice William Douglas frequently recused himself from cases involving the Securities and Exchange Commission, for which he had served as Chairman (Reference WeaverWeaver 1975), and Chief Justice Earl Warren recused himself from cases that touched upon his work as governor (Reference LewisLewis 1958). Because most of this behavior will have occurred before the justices were appointed to the Court, it is reasonable to assume that recusals will occur more frequently at the beginning of a justice's term in office, when litigation is more likely to touch upon their pre-bench activities:

H3: Justices are less likely to recuse themselves as their term in office increases.

I also expect that over time the relationship between years of service and recusals will become attenuated. The importance of an additional year of service will be less important as the temporal distance from pre-bench conflicts becomes increasingly remote:

H4: Over time, the relationship between years of service and recusals is likely to become attenuated.

Two forms of previous work experience are particularly likely to prompt recusals and should be considered separately. First, several of the justices served as Solicitors General before becoming justices.Footnote 19 Because the Solicitor General represents the federal government in the Supreme Court, it is reasonable to expect that former Solicitors General will have participated in cases that subsequently come before the Court, prompting these justices to recuse themselves more often:

H5: Justices are more likely to recuse themselves from cases when they have previously served as Solicitors General.

Also more likely to recuse themselves are justices who have had federal appellate experience. Justices who have served on the U.S. Courts of Appeals are likely to have already participated as judges in cases that later come to the Supreme Court. For example, Chief Justice Roberts recused himself from Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006), concerning the Bush administration's use of military commissions to try detainees as Guantanamo Bay, because he had served on the three-judge panel on the D.C. Circuit that reviewed the case:

H6: Justices are more likely to recuse themselves from cases when they have had federal appellate experience before becoming justices.

Because the effects of these particular forms of service on recusal behavior are also likely to diminish with time, I hypothesize that there will be statistically significant interactions between years of service and a justice's prior work experience as a judge or the Solicitor General.

Policy Considerations

While I expect the justices generally to follow the statutory recusal guidelines, I also expect the justices to be less likely to recuse themselves when their participation in cases serves to advance their policy goals. I do not mean to suggest that justices never disqualify themselves from cases in which they have substantive policy interests. Many times the arguments in favor of recusal will be too strong, regardless of the justices' interest in participating. My suggestion is subtler, that often the arguments in favor of recusal are not decisive, and in these circumstances the justices will err on the side of not recusing themselves when they have strong incentives to participate. Because the justices do not report the reasons for their recusal decisions, they can obscure their motivations when they wish to participate on policy grounds.

Specifically, I expect the justices' incentives to recuse themselves to vary depending on their distance from the Court's median. Much literature has focused on the question of which justice plays the most pivotal role in determining the Court's policy output. Some research has focused on the Court median because that justice determines the disposition of case outcomes (Reference Martin, Quinn and EpsteinMartin, Quinn, and Epstein 2005), while other research has focused on the role of the median member of the signing coalition in determining the content of majority opinions (Reference BonneauBonneau et al. 2007; Reference CarrubbaCarrubba et al. 2012; Reference Clark and LauderdaleClark and Lauderdale 2010). Still other research has suggested that the median justice varies depending on the issue area (Reference Lauderdale and ClarkLauderdale and Clark 2012), and that the pivotal “swing” justice in a case is not necessarily the Court median (Reference Enns and WohlfarthEnns and Wohlfarth 2013).

When it comes to understanding the justices' recusal practices, I focus on the Court median because justices are less likely to know the identity of other pivotal justices at the time that they are making recusal decisions. In general, justices decide whether to recuse themselves from cases before the oral arguments have occurred. While the justices can make educated guesses about who the members of majority coalitions will be before the arguments, they make use of the information obtained in oral arguments to make more precise predictions (Reference Black, Johnson and WedekingBlack, Johnson, and Wedeking 2012). Before the arguments, the best heuristic that justices can use to determine whether their policy goals will be threatened by recusals is the identity of the Court median.

I expect that justices who are close to the Court's median will be less likely to recuse themselves from cases. These justices, by virtue of their proximity to the median, will see their votes as potentially pivotal to determining the disposition, particularly if the Court's median does not vote as expected. Research by Reference Enns and WohlfarthEnns and Wohlfarth (2013) suggests that the swing justice on the Court is not necessarily always the median, so it would be reasonable for justices who are close to the Court's median to anticipate that their votes could be decisive:

H7: Justices are less likely to recuse themselves from cases when they are close to the Court's median.

I also anticipate, for different reasons, that justices who are far from the Court's median will have incentives to participate, and that they will therefore be less likely to recuse themselves. Justices who are far from the Court's median will not expect their preferences to be reflected in the proceedings unless they participate, if only to dissent. While these justices might not expect to serve as swing justices, they might still hope to influence the contents of opinions. If opinion content is determined by the coalition medians (e.g., Reference CarrubbaCarrubba et al. 2012), then it is reasonable for justices at the extremes of the Court to think that their participation will matter by shifting coalition medians in their direction, assuming that they are in the majority:

H8: Justices are less likely to recuse themselves from cases when they are far from the Court's median.

I expect the justices in between these two extremes, neither close to the Court's median nor at the ideological poles, to withdraw at the baseline rate. These justices are not close enough to the Court's median to expect the disposition to turn on their judgment—they might even lie outside the minimum coalition necessary for obtaining a specific outcome—but neither are they far enough away to feel like outliers whose views will be unrepresented unless they participate.

Institutional Considerations

Justices who decline to recuse themselves from cases for institutional reasons will be motivated by a duty to sit that is grounded in concern about how their absence from disputes will impair the capacity of the Court to decide cases and controversies. Participation also promotes clarity in the law, which is a goal that the justices have been known to pursue at the agenda-setting stage (Reference Black and OwensBlack and Owens 2009; Reference PerryPerry 1991; Tanenhaus, Schick, and Reference Tanenhaus, Schick, Rosen and SchubertRosen 1963) and the decision on the merits (Reference Lindquist and KleinLindquist and Klein 2006). The justices have expressed particular concerns about the possibility of dividing evenly (Reference GinsburgGinsburg 2004; Reference RobertsRoberts 2011), so one might expect the justices to feel that their participation is most required when they think that cases will be close.

That is to say, when cases are likely to be divisive, recusals should be less common. While the justices might not be able to predict the final vote on the merits precisely at the time of their recusal decisions, they probably have a good sense of when cases are likely to be close. For example, when cases have divided the lower courts, the justices might expect that the same legal questions will be divisive on the Supreme Court:

H9: Justices are less likely to recuse themselves from cases that have generated a conflict in the lower courts.

Conflicts among the lower courts indicate that case dispositions are not obvious, either because of legal uncertainty or because the issues are ideologically divisive (Reference Corley, Steigerwalt and WardCorley, Steigerwalt, and Ward 2013; Reference PerryPerry 1991). Either way, the justices are likely to feel that their participation is necessary to bring clarity to the law, causing them to avoid recusing themselves in these circumstances. Similarly, when a judge below has dissented, the justices might feel that their participation is warranted:

H10: Justices are less likely to recuse themselves from cases when one of the judges in the court below has dissented.

Just as a conflict among the lower courts is an indicator of divisiveness, so too is the presence of a dissent because the dissent rate on lower courts tends to be low (Reference Hettinger, Lindquist and MartinekHettinger, Lindquist, and Martinek 2004, Reference Hettinger, Lindquist and Martinek2006). As Reference Edelman, Klein and LindquistEdelman, Klein, and Lindquist (2008: 836) explain, “the presence of a dissent in a lower court decision is a strong indication that reasonable people could disagree about the right answer in a case and might tend to diverge along ideological lines.” Justices might predict that they will be less likely to achieve consensus in these cases, leading them to disqualify themselves less frequently.

Even when cases are not expected to be close, the justices might feel a responsibility to resolve controversies in important areas of law. For example, when cases are salient, recusals are likely to be less common because salient cases are more likely to present important questions of federal law that the justices will wish to clarify. The justices might also anticipate having difficulty achieving consensus in salient cases. Reference Corley, Steigerwalt and WardCorley, Steigerwalt, and Ward (2013: 91) observe that “cases with a high degree of salience to external political actors and the public are salient to the justices as well and therefore more likely to expose divisions among them.” If salient cases are more divisive, then justices might perceive a greater possibility of dividing evenly were they to sit out:

H11: Justices are less likely to recuse themselves from salient cases.

In contrast, I expect recusals to be more likely to occur in statutory cases. In matters of constitutional interpretation, the justices are the final arbiters, and this heightened institutional responsibility is likely to create incentives for the justices to participate in order to clarify points of law. However, statutory cases are open to revision by Congress, so the stakes are likely to be lowered somewhat.Footnote 20 Reference Corley, Steigerwalt and WardCorley, Steigerwalt, and Ward (2013: 75) have also suggested that statutory cases are less divisive than constitutional cases: “The language of statutes is generally more detailed and less ambiguous than the language of the Constitution, which makes it easier for judges to determine legislative intent and plain meaning when interpreting them.” Altogether, these considerations suggest that justices will have fewer incentives to participate in statutory cases:

H12: Justices are more likely to recuse themselves from statutory cases.

Uniting these hypotheses is the expectation that the justices do not attend strictly to the recusal guidelines established by Congress because they have other goals that may trump the need for impartial justice. Reducing bias is important to the justices, but it is a goal that they pursue in tandem with their substantive policy goals and their institutional responsibility to decide cases and promote clarity in federal law. This paper does not take a position on which of these goals is the most important to the justices or, indeed, why they might be concerned with promoting clarity. It could well be that the justices will choose to foster clarity in a way that is consistent with their sincere policy preferences. That justices care about their institutional responsibilities does not preclude them from behaving attitudinally (Reference Black and OwensBlack and Owens 2009). My point is that there are strong theoretical reasons for thinking that the justices routinely pursue institutional and policy goals that have nothing to do with the statutory recusal requirements. If Reference RobertsChief Justice Roberts (2011: 10) insists that the justices are “deeply committed” to serving as “an impartial tribunal governed by the rule of law,” these claims warrant further scrutiny.

Research Design

To test my hypotheses I used Reference SpaethSpaeth's Supreme Court Database (2011, Release 03). Because my unit of analysis is the justice, I used the justice-centered data, which include separate entries for every justice who participated in each case.Footnote 21 The dependent variable is a dummy variable measuring whether a justice sat out of a dispute. It is based on the Vote variable in Spaeth's justice-centered database, which records how a justice voted on the merits. When the value of Vote is listed as missing (“.”), it indicates that a justice was on the bench but did not participate. A check of these cases in Lexis confirms the accuracy of the coding. For example, in Howsam v. Reynolds (2002), the Vote entry for Justice O'Connor is listed as missing in Spaeth's database, and the headnotes in Lexis indicate that “O'CONNOR, J., took no part in the consideration or decision of the case.” Later that same term, in PacifiCare Health Systems v. Book (2003), Justice Thomas's Vote is missing, and the Lexis headnotes confirm that he “took no part in the consideration or decision of the case.” I coded the dependent variable “1” when a justice did not participate and “0” otherwise. The mean value of the recusal variable is 0.0208, which means that justices on average sit out of cases about 2.1 percent of the time.

Because I am only interested in recording circumstances in which justices voluntarily recused themselves from cases, it was necessary to isolate entries in which justices withdrew because of illness or because they were appointed after the oral arguments. Votes in these circumstances are also recorded as “.” in Spaeth's database but needed to be recoded “0.” To identify these cases, I followed procedures developed by Reference Black and EpsteinBlack and Epstein (2005). Cases were recoded “0” when the date of a justice's appointment came after the oral argument.Footnote 22 Cases were also recoded “0” when justices withdrew from at least four cases on consecutive dates of oral argument, because this behavior is consistent with illness.Footnote 23 It is possible that the dependent variable still captures a few circumstances in which justices withdrew because of illness, but I have no theoretical reason to assume that the inclusion of these cases has changed the results by very much or biased them in ways that favor my hypotheses. If anything, including these cases makes it harder for the principal explanatory variables to attain significance.

The first set of independent variables is used to test hypotheses relating to statutory motivations for recusals. The Business Petitioner/Respondent variable is coded “1” when the petitioner or the respondent is a business, corporation, or financial institution, “2” when both the petitioner and the respondent are one of these institutions, and “0” when neither is. I expect the Business Petitioner/Respondent variable to be positively correlated with the dependent variable. It is based on the Petitioner and Respondent variables in Spaeth's database, which classify petitioners and respondents by type.Footnote 24 The Net Worth variable measures the annual “net worth” of each justice, recorded in millions, as reported in their financial disclosure forms. To keep the data comparable, figures were converted into 2010 dollars. Also, because the Net Worth variable only includes data beginning with 1980, when financial disclosure forms became available, it is included in a separate model to avoid unnecessarily truncating the data.

The Years of Service variable is a count variable recording the number of years that a justice has served on the Court at the time of their vote. I expect Years of Service to be negatively correlated with recusals. I also include a squared version of this variable (Years of Service)2 to test the hypothesis that the effects of years of service become attenuated over time. The Solicitor General variable is a dummy variable recording whether a justice previously served as the Solicitor General.Footnote 25 The Federal Appellate Experience variable records whether a justice served on the U.S. Courts of Appeals.Footnote 26 I expect both variables to be positively associated with recusals. I also included two interaction terms to assess whether time diminishes the influence of a justice's experience as the Solicitor General (Years of Service* Solicitor General) or a federal judge (Years of Service* Federal Appellate Experience).

The second group of variables focuses on policy-based reasons for recusals. The Ideological Distance from Court Median variable is based on the Reference Martin and QuinnMartin and Quinn (2002) scores and represents the absolute value of the difference between the ideology score of a justice and the median justice for the Court that term. Because I expect the effects of ideological distance to change as the distance from the median increases, I modeled it as a third-order polynomial, which was the best fit for the data. These effects are captured by the inclusion of two additional variables: (Ideological Distance)2 and (Ideological Distance)3.

The final set of variables focuses on institutional reasons for recusals. The Conflict variable is a dummy variable adapted from the certReason variable in Spaeth's database, assigned a value of 1 when the justices have reported division or uncertainty in the courts below.Footnote 27 I expect it to be negatively associated with recusals. Dissent Below is adapted from Spaeth's lcDisagreement variable, coded 1 when there is mention in the majority opinion of a dissent in the court below. Case Salience is based on Reference Epstein and SegalEpstein and Segal's (2000) measure of whether a case was featured on the front page of The New York Times.Footnote 28 I expect it to be negatively associated with recusals. The Statutory variable is a dummy variable derived from Spaeth's lawType variable, coded 1 when a case involves a matter of statutory interpretation, with the expectation that it will be positively associated with recusals.Footnote 29

Because the dependent variable is dichotomous, I used logistic regression. Logit was preferred to probit because a comparison of the models indicated that logit was the better fit. The Akaike information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion were consistently lower for the logit models, indicating a better fit. Because I used the justice-centered data, with multiple entries for each case, I clustered by CaseID, using the same variable from Spaeth's database. I also introduced dummy variables for each of the justices.Footnote 30

Results

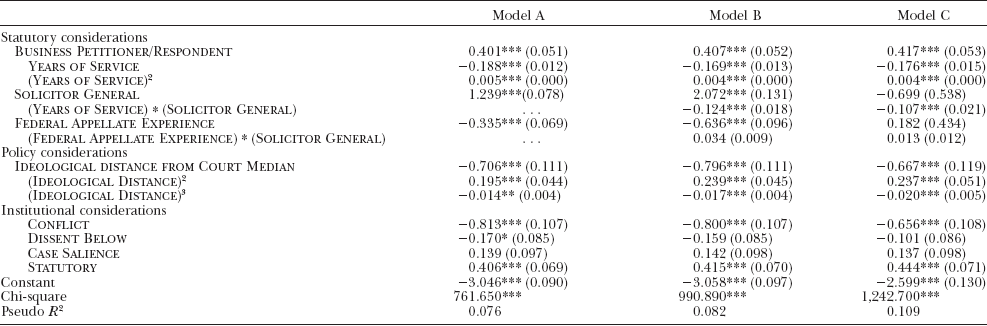

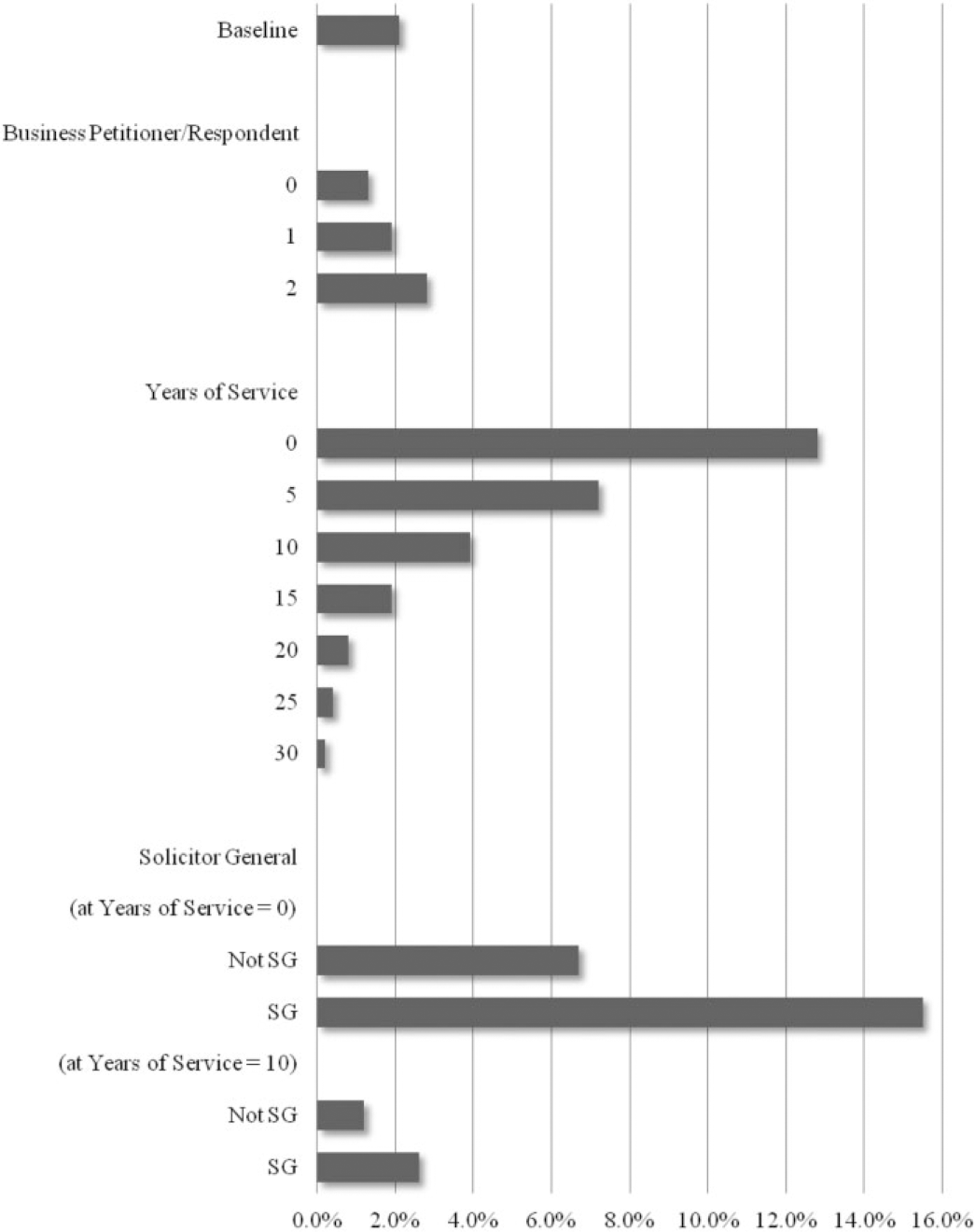

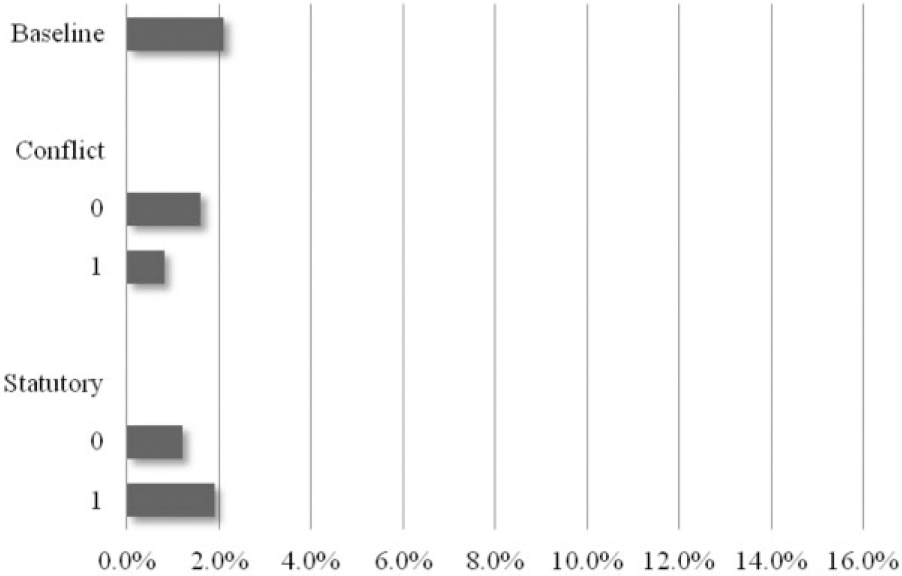

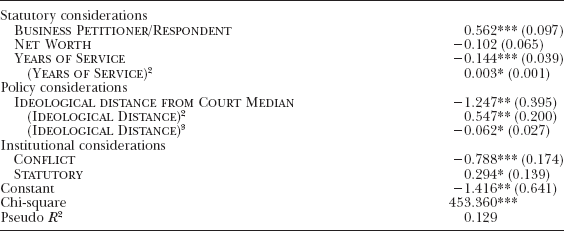

The results are presented in Table 1 in three columns. Model A presents the key explanatory variables, while Model B introduces the interaction terms and Model C is robust to the introduction of justice dummy variables, the coefficients for which are not reported in Table 1 but are included in the appendix. With a few exceptions, the results are consistent with expectations. Looking first at the statutory variables, the results indicate that justices are more likely to recuse themselves from cases when a business, corporation, or financial institution is the petitioner or respondent, or both (Business Petitioner/Respondent). The effects of this variable are presented in Figure 3, which reports the predicted probability of a recusal for selected values of the statutory variables.Footnote 31 When a business interest is not before the Court (Business Petitioner/Respondent = 0), the likelihood of a recusal is about 1.2 percent, but when at least one business interest is represented as either the petitioner or the respondent (Business Petitioner/Respondent = 1), the likelihood increases to 1.9 percent. When both the petitioner and the respondent represent business interests (Business Petitioner/Respondent = 2), the likelihood of a recusal is about 2.8 percent, a total difference of about 1.6 percentage points. The effect is substantively small, but it should be remembered that the baseline probability of a recusal is low to begin with, at about 2.1 percent.

Table 1. Logit Model of Recusals, 1946–2010

* p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Note: N = 73,811. Model A includes all variables except the interaction terms, Model B introduces the interaction terms, and Model C includes dummy variables for each justice (the coefficients for which are not reported but are included in the appendix).

Figure 3. Probability of a Recusal, Statutory Considerations.

Larger substantive effects are generated by the number of years that a justice has served on the bench (Years of Service). Figure 3 illustrates that when justices are first appointed, they recuse themselves from about 12.8 percent of cases, but by their 10th year they disqualify themselves from just 3.8 percent of cases. By 20 years the recusal rate falls to 0.8 percent. Substantively, this finding makes sense, as many of the conflicts of interest that prompt recusals derive from pre-bench activities. As time increases, and these activities become more remote, there is less of a chance that they will impact the justices' current caseload. Table 1 also affirms that the effects of years of service become attenuated with time, as indicated by the fact that the (Years of Service)2 variable is statistically significant and signed opposite from the Years of Service variable.Footnote 32 This finding is consistent with expectations because one would not expect the difference between the first and second year of service to be the same as the difference between the 10th and 11th years. Indeed, Figure 3 illustrates this trend. Between 0 and 5 years of service, the likelihood of a recusal drops by 5.6 percentage points, but between 10 and 15 years of service, the likelihood falls by just 1.9 percentage points.

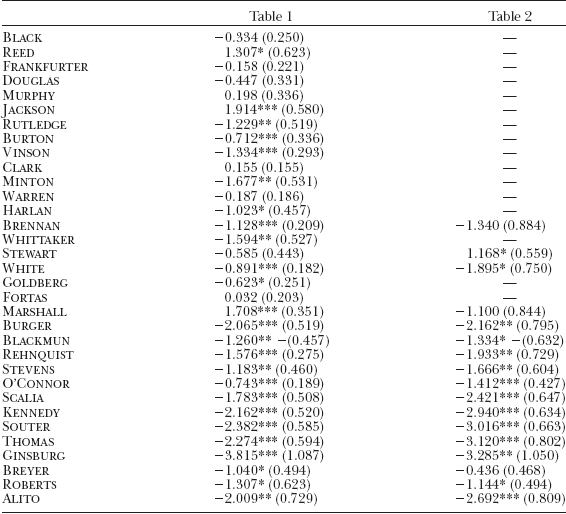

Table 1 also reports that justices who have served as Solicitor General are more likely to recuse themselves from cases, and that the interaction between the Solicitor General and the Years of Service variable is significant. Substantively, this finding suggests that the importance of having served as the Solicitor General decreases over time as the distance from the experience becomes remote. Figure 3 shows that in the first year of service, a former Solicitor General is 8.8 percentage points more likely to withdraw from cases, but by the 10th year the likelihood increases by just 1.3 percentage points. These results should be interpreted with caution, however, because they are not robust to the introduction of the justice dummy variables.

Contrary to expectations, Federal Appellate Experience does not increase the likelihood that justices withdraw from cases. Columns A and B of Table 1 suggest that there is a statistically significant relationship, but in the opposite direction as hypothesized. That is to say, justices with prior experience as federal appellate judges are less likely to recuse themselves from cases. The reason for this result is not immediately clear. It is possible that prior judicial experience familiarizes justices with federal recusal requirements, leading them to behave in ways that minimize the possibility of conflicts of interest. For example, former judges might know how to structure their financial affairs so as to avoid having direct ownership stakes in corporations that litigate frequently in the federal courts. These possibilities should be explored in future research. It should be noted, however, that the coefficient for Federal Appellate Experience is not robust to the introduction of justice dummies.

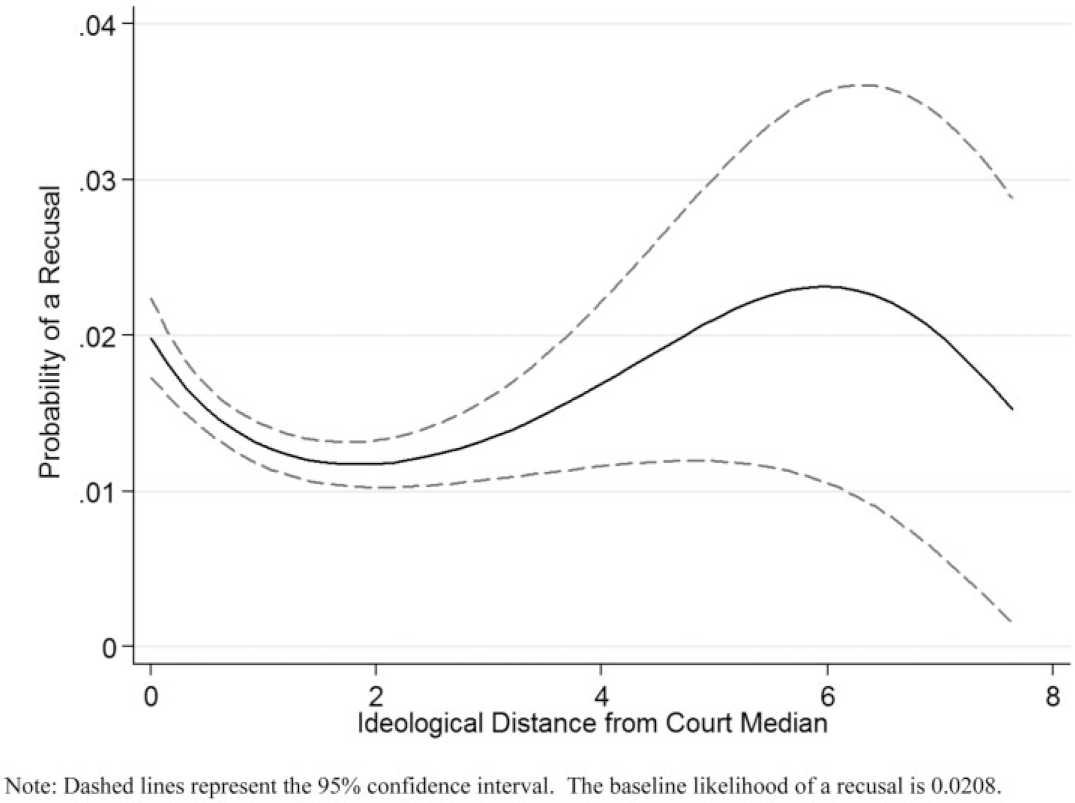

Turning to policy-based explanations for recusal practices, Table 1 finds support for the influence of ideology on the justices' behavior. The Ideological Distance from Court Median variable is statistically significant, as are the squared (Ideological Distance)2 and cubed terms (Ideological Distance)3. The effects of these variables on the probability of a recusal are illustrated in Figure 4.Footnote 33 Because the Ideological Distance variable was modeled as a third-order polynomial, the graphical representation of the marginal effects is curvilinear and changes directions twice. Initially, the likelihood of a recusal decreases as a justice's ideological distance moves away from the Court median. This trend is consistent with my expectation that justices who are close to the Court median will be less likely to recuse themselves from cases because their proximity to the median enhances their sense of influence over the case disposition. Justices near the center of the Court will resist disqualifying themselves from cases because they anticipate that they could serve as the swing vote if the Court's median does not vote as expected, giving them control over the disposition. Alternatively, justices who are close to the median might expect to serve as part of a minimum winning coalition, increasing their incentives to participate.

Figure 4. Probability of a Recusal by Ideological Distance from Court Median.

As the ideological distance increases further, the effect of ideology shifts and the probability of recusing increases, leveling out near the baseline probability of about 2.1 percent. This trend is also consistent with expectations because justices who are neither close to the Court's median nor far from it lack special incentives to participate, instead disqualifying themselves at the baseline rate. Finally, as the ideological distance from the Court's median increases to its furthest point, the likelihood of a recusal drops again, falling below the baseline. These justices, at the ideological extremes of the Court, are likely to feel that their participation is needed for their attitudes to be represented. Interestingly, an implication of Figure 4 is that Court medians recuse themselves from cases more frequently than other justices near the center of the Court. This finding is counterintuitive but might reflect the fact that other justices simply have greater incentives to participate than Court medians, who withdraw at the baseline rate.

Turning next to institutional considerations, one of the variables does not attain statistical significance (Case Salience) and one is only significant in Column A (Dissent Below). However, two other variables (Conflict and Statutory) do perform as hypothesized and are robust to the introduction of the justice dummies. Their effects on the probability of a recusal are reported in Figure 5. The results indicate that when there is a Conflict reported in the courts below, justices are less likely to disqualify themselves from cases, decreasing the rate of recusal from about 1.6–0.8 percent. Substantively, the most likely explanation for this finding is that justices avoid withdrawing from cases that they expect to be close. Justices may feel that their participation is necessary in order to prevent the Court from dividing evenly, or because they feel an institutional obligation to participate in the resolution of these cases. Figure 5 also indicates that there is a significant association between recusals and Statutory cases. When cases involve statutory interpretation, the likelihood of a recusal increases from 1.2 to 1.8 percent. The most likely explanation for this finding is that justices feel that their participation is less essential because, unlike constitutional cases, statutory decisions are open to revision by Congress. The justices might also have an easier time achieving consensus in statutory cases (Reference Corley, Steigerwalt and WardCorley, Steigerwalt, and Ward 2013), easing concerns about dividing evenly.

Figure 5. Probability of a Recusal, Institutional Considerations.

Finally, Table 2 estimates a new model using only data from 1980. The new model includes the Net Worth variable, making it possible to test the hypothesis that recusals are more likely when the net worth of the justices increases. The model also permits one to observe whether the effects of the other key explanatory variables remain significant when just the post-1980 data are examined. Table 2 includes only variables that were statistically significant in Table 1 and coefficients are robust to the introduction of the justice dummies. The results indicate that there is not a relationship between the Net Worth of the justices and their recusal practices, but the other explanatory variables do perform as expected in the post-1980 models. The effect of business interests litigating before the Court remains significant (Business Petitioner/Respondent), as do the effects of years of service (Years of Service, Years of Service)2, ideology (Ideological Distance from Court Median, Ideological Distance2, Ideological Distance)3, and the presence of a conflict in the lower federal courts (Conflict). The effects of the Statutory variable diminish somewhat in the new model. However, on the whole, the results in Table 2 affirm once again that the decision to withdraw from a case reflects a combination of statutory, policy, and institutional incentives.

Table 2. Logit Model of Recusals, 1980–2010, with the Justices' Net Worth

* p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Note: N = 31,918. Results are robust to the inclusion of justice dummy variables (the coefficients for which are not reported but are included in the appendix).

Conclusion

Altogether, the results of this study suggest that the justices do not rely exclusively on statutory or ethical criteria when making recusal decisions, but neither do they ignore these criteria. I find that justices are more likely to disqualify themselves from cases when businesses, corporations, and financial institutions are before the Court, which is what one would expect to observe if the justices were recusing themselves regularly because of financial conflicts of interest. I also find that the justices are more likely to withdraw from cases in their initial years of service, when their pre-bench activities are more likely to impact on their service as justices. These findings provide evidence that the justices are compliant with the ethical guidelines that are prescribed in 28 U.S.C. § 455. On the occasions when one would expect the justices to encounter the sorts of ethical conflicts covered by the statute, we find a greater number of recusals.

However, the analysis has also found evidence that institutional and policy motivations influence recusal behavior. The results indicate that the justices take the “duty to sit” seriously and are less likely to withdraw from cases that have divided the lower federal courts. Normatively, it is not necessarily problematic if the justices avoid recusing themselves from divisive cases because participating enables the justices to fulfill their institutional responsibilities to resolve disputes and bring clarity to the law. Yet, the behavior is also in tension with the objectives of the recusal statute. If the justices participate disproportionately in conflict cases, the suggestion is that the justices might not be strictly following the statutory guidelines, and that they might therefore be participating in some cases despite their biases.

More troubling, from a normative standpoint, is the finding that recusal behavior is correlated with the justices' policy preferences. I find that justices who are close to the Court's median are less likely to disqualify themselves, most likely because they know that case dispositions, which are typically set by the Court's median, could turn on their participation. Justices who are very far from the Court's median are also less likely to withdraw, because these justices are likely to feel that their views on cases will not be represented unless they participate. The findings are consistent with previous research on judicial behavior, which has found that the justices are policy oriented (e.g., Reference Segal and SpaethSegal and Spaeth 2002), but the findings are in tension with the statutory requirements as well as norms of judicial ethics. While some might argue that it is permissible for justices to bend statutory guidelines to fulfill their institutional responsibilities, fewer would maintain that justices should decline to recuse themselves simply to achieve policy goals. Indeed, the findings lend support to critics who say that the recusal process requires more transparency and accountability (Reference FrostFrost 2005; Reference GoodsonGoodson 2005; Reference Lubet and DiegelLubet and Diegel 2013).

Minimally, then, it would seem that the justices are not being entirely candid about their recusal practices. Yet, society lacks the information it needs to scrutinize particular recusal decisions and to hold justices accountable to the ethical guidelines because most of the deliberations over the justices' recusal behavior are undocumented. The justices' silence stands in stark contrast to the lengths that they take to explain their decisions on the merits. Written opinions are considered to be important because they serve as sources of law for lower courts to apply, but more than this, they serve to enhance the Court's legitimacy by cultivating a perception that Supreme Court justices are principled decision makers (Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson and Caldeira 2009, Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011). Even when their behavior is motivated by policy, the justices can build confidence in the institution by offering reasons for their decisions that can withstand public scrutiny.

It is puzzling, then, that the justices refuse to defend their recusal practices. Candor would seem only to benefit them. By explaining their justifications in writing, the justices could preempt charges of bias by putting out in the open their potential conflicts of interest and describing the principles that they use to deal with them. The practice would reinforce the public's perception that the justices are principled decision makers and help to rebut the criticisms of their recusal practices that periodically arise. Creating a written record would also enable the justices to codify their practices, in the form of precedent, making it easier for them to determine in the future when recusals are warranted. The justices might even find that they withdraw from cases less frequently by reaching consensus about when disqualification is necessary, thereby reducing the number of cases in which their membership is down.

On the other hand, maintaining secrecy about the recusal process gives the justices greater flexibility to pursue other institutional and policy goals. A written record of past recusal decisions might unduly hamper the justices, obligating them to withdraw from cases when analogous circumstances arise, even when there is the risk of dividing evenly or lacking a quorum. Of course, Congress has the capacity to remedy this problem. One proposal, introduced by Senator Patrick Leahy, would have permitted retired justices to replace temporarily justices who recused themselves (Reference RotundaRotunda 2010). In the absence of these remedies, however, the justices must contend with the reality that they have no substitutes. Confronted with the choice of damaging the Court's reputation or compromising its efficiency, it serves the justices to say nothing at all, making no formal statements and providing no written records, leaving society with few resources to hold the justices accountable to ethical standards.

This study has examined only aggregate behavior and so I have not investigated more particularized conflicts of interest that might cause justices to recuse themselves. Future research can further probe the justices' financial disclosure forms to determine, on a case-by-case basis, whether the justices recuse themselves from cases in which the financial interests they list are implicated. Research might also compare the justices' recusal practices with occasions in which calls for recusal are reported in the popular media. Such analyses would provide more nuance to the findings presented here. However, I would not expect the basic conclusions of the study to change. The justices might follow statutory guidelines for recusals, but they do not follow them strictly. Other institutional and policy considerations also guide their behavior and are determinative in some circumstances. With so much at stake, and with no one to direct them otherwise, justices have strong incentives to participate in cases that serve these interests.

Appendix. Coefficients for Individual Justices

* p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Note: The appendix includes the justice coefficients that were excluded from Tables 1 and 2; other coefficients are as reported in those tables. In both columns, Justice Powell is the baseline and the coefficients for Justices Sotomayor and Kagan are not reported because of the recency of their appointments to the Court.